The recent Covid-19 pandemic has prompted renewed appraisals of what makes health systems work – how did different countries cope with the challenges of the pandemic? For Latin America, the overall picture is still inconclusive. In the more pessimistic analyses, countries of the region were ill-prepared for pandemic response and lacked sophisticated social safety nets. The ferocious early wave of Covid-19 in Ecuador, the record-high mortality in Peru, or political divisions over pandemic response in Brazil all seem to substantiate this negative take on Latin America’s resilience to health crisis. Such a perspective shares some ground with Marcos Cueto and Steven Palmer’s historically informed notion of a “culture of survival” in the region, meaning that “most health interventions directed by states have not sought to resolve recurrent and fundamental problems that, in the final analysis, have to do with the conditions of life.”Footnote 1

A more optimistic reading of the situation is that the health and safety of the average person in Latin America is now more highly valued and protected than ever. Across Latin America, there is a broad consensus that health is a human right and that well-functioning health systems may serve as a compensating mechanism for the inequalities that typify many Latin American societies.Footnote 2 Some governments performed admirably during the pandemic, not just in places that might be viewed as anomalously efficient (Costa Rica, Uruguay) but also in countries like Ecuador, which, only a year after experiencing the early terrors of the pandemic, rolled out one of the fastest vaccination campaigns in history. In countries where the pandemic response has been disastrous, it is usually because political leaders have gone against the advice of their health experts; the capacity for a more humane, consistent and effective response exists, but may be underutilized. From this vantage point, the pandemic demonstrates Cueto and Palmer’s contrasting concept, “health in adversity,” which “seeks to register the sanitary gains that have been achieved, despite the discourses and practices of hegemonic power, in terms of the adaptations born of questioning, resisting, and proposing alternatives.” This view emphasizes the “work of many health professionals, activists, and popular leaders who have developed holistic projects and tried to modify the vicious cycle of poverty–authoritarianism–disease in favor of a more inclusive society and public health.”Footnote 3

The spirit of “health in adversity” is embodied in Latin American social medicine, an academic and political movement that, while often working at the margins, has made an outsized impact on health across the region. Many Latin American countries have been able to build robust health systems and raise living standards under conditions of adversity. This change – some might call it progress – did not come overnight, and without tremendous ingenuity, sacrifice, and collective effort. This progress, I would argue, could not have happened without social medicine’s efforts to promote health equity.

Latin American social medicine (LASM) is a field that helped produce broad-based public health improvements across the region in the twentieth century. However, the deep historical roots, institutional bases, political influence, and public health achievements of LASM have received scant attention, even with rising interest in the subject among scholars and public health practitioners.Footnote 4 In this chapter, I seek to understand the ideological roots of social medicine, how institutional and interpersonal networks supported the diffusion and development of social medicine in Latin America, and how ideas in social medicine translated into social policy. I analyze the shortcomings of previous treatments of the history of social medicine in Latin America and elsewhere, and explain the outline of a useful new narrative of the movement.Footnote 5

First-wave social medicine grew out of the scientific hygiene movement, gained strength in the interwar period, and left its imprint on Latin American welfare states by the 1940s. Second-wave social medicine, marked by more explicitly leftist analytical frameworks, took shape in the early 1970s and crystallized institutionally in the Latin American Social Medicine Association (ALAMES) (regionally) and Brazilian Association of Collective Health (ABRASCO) (in Brazil). It is certainly possible to treat these waves as separate and unconnected, given some important differences in theoretical foundations and political praxis. However, I argue that a dialectical process links these two waves into a single history. Early social medicine demands, once institutionalized in welfare states and the international health-and-development apparatus, led to complacency and ineffective bureaucratic routines, which in turn sparked critical reflection, agitation for change, and a new wave of social medicine activism. Disaffected technocrats, often in exile from authoritarian regimes, became the essential nucleus for a second wave of Latin American social medicine. From its rebirth in unorthodox academic networks, LASM would become institutionalized in university programs and help spark national health systems reforms, first in Brazil and eventually in an array of leftist “Pink Tide” governments of the 2000s.

The Contested Historiography of Social Medicine

Social medicine has sometimes been a slippery subject in the historiography of public health and medicine in Latin America. There are three mostly separate scholarly conversations about LASM, crafting different narratives for slightly different audiences: treatments by academic historians of the first wave of social medicine in the region, roughly around the 1920s to the 1940s; an interdisciplinary exploration of the more recent wave of social medicine, starting in the 1970s; and the stories told by LASM insiders and their allies in the North American academy, which paints a portrait of an LASM movement with deep historical roots in European revolutionary socialism going back to the middle of the 1800s.

The mainstream historiography of public health, medicine, and the welfare state in Latin America recognizes a vibrant social medicine movement in the early twentieth century. Case studies from Peru, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Chile suggest that interest in social medicine emerged around the same time in many countries, prompting policy discussions that often led to more robust national systems of social insurance or socialized medicine.Footnote 6 Historical accounts of other fields, like eugenics, puericulture, and hygiene, point to overlaps or dialogues with social medicine. In this line of historical research, the connections between national-scale social medicine movements are often unspecified. But international institutions (such as the International Labor Organization [ILO] or the League of Nations Health Office [LNHO]) and social policy entrepreneurs (like René Sand of Belgium), are frequently cited for disseminating social medicine ideas from Western Europe to Latin America.Footnote 7

A separate line of research seeks to account for the origins of a second wave of Latin American social medicine, starting around the early 1970s and into the present day. Here, the work of Brazilian scholars stands out for explorations of the country’s collective health (saúde coletiva) movement, its institutionalization in university programs and civil society organizations, and its influence on milestone reforms to the Brazilian health system in the 1980s (see de Camargo, Chapter 11 in this volume).Footnote 8 Other scholars have helped reconstruct the often clandestine international networks that connected social medicine thinkers and practitioners together in the 1970s and early 1980s, when authoritarian governments suppressed leftist thought and forced many health professionals into exile.Footnote 9 Participants in second-wave LASM organizations like ALAMES have also contributed accounts of social medicine’s origins, including colonial-era antecedents.Footnote 10 And historians are now piecing together a more comprehensive history of this era (see Fonseca, Chapter 8 in this volume).

However, the most prominent historical narrative of LASM traces its origins back to the foundational figure of Rudolf Virchow. This pioneering Prussian-German pathologist was active politically in his early career, and his diagnosis of the roots of a typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia in 1848 anticipates the “biosocial” lens of integrative fields like social medicine and social epidemiology (see Timmermann, Chapter 1 in this volume). This standard history of social medicine, with origins in the revolutionary year of 1848, was first crafted by a group of politically progressive European and US historians in the 1930s and 1940s. Henry Sigerist, George Rosen, and Edwin Acknerknecht, in particular, first constructed the image of Virchow as the founder of social medicine, over and above his long-recognized contributions as a pioneer in cellular pathology.Footnote 11 Later Sigerist’s work was taken up by figures like Milton Roemer, Milton Terris, Vicente Navarro, Gustavo Molina Guzmán, Elizabeth Fee, Nancy Krieger, and Paul Farmer, who represent a vocal leftist-progressive front against business-as-usual in the health field. Virchow’s name is often invoked as a symbol of social medicine’s transformative potential and revolutionary credentials, as in a 2021 New York Times commentary by epidemiologist Jay S. Kaufman.Footnote 12

The genealogical connection between LASM and the founding father figure of Rudolf Virchow became a received narrative through the work of the US sociologist-physician Howard Waitzkin. In a series of articles and books published in the early 2000s, Waitzkin contended that Virchow’s student in Germany, Max Westenhöfer, became a mentor to a young Salvador Allende in Chile of the 1930s and inspired his political activism, in the health sector and beyond.Footnote 13 This narrative is alluring because of its uncanny historical continuity, with a thread connecting early leftist revolutionaries of Europe to the first wave of social medicine in Latin America, and, over the long arc of Allende’s political career, to later promises of socialist governance and its sudden end in the violence of dictatorship – which, in turn, gave rise to the neoliberal development model against which second-wave social medicine has built its identity. Waitzkin’s narrative has been widely cited, and often much simplified, in sympathetic accounts of LASM in the Anglophone academic world.Footnote 14

As I have detailed elsewhere (with Marcelo Sánchez Delgado), this version of the history of Latin American social medicine, especially those claims of Virchow’s or Westenhöfer’s influence on early Latin American social medicine, demands reconsideration.Footnote 15 The main problem is that during social medicine’s first wave in Latin America, before historians like Sigerist began to revive the memory of Virchow, he was considered a pioneering biomedical researcher but seldom, if ever, invoked as a forerunner of social medicine. The association between Westenhöfer and Allende is tenuous, if it existed at all, and they did not align ideologically, given that Westenhöfer supported the Third Reich and Allende was resolutely anti-fascist. Additionally, circulation of social medicine ideas, in Chile and across Latin America, clearly predate Allende’s medical and political career, although he did become a major figure in Chilean social medicine in the 1930s, as explained below.

More generally, histories of LASM written by committed members of the movement today overlook inconveniently non-leftist social medicine figures of the early twentieth century (such as Carlos Paz Soldán of Peru, Eduardo Cruz-Coke in Chile, or Ramón Carrillo in Argentina); raise up symbolic movement avatars like Che Guevara, who was actually uninvolved in social medicine networks during his lifetime; erase vibrant ideological debates within the movement; and neglect the reasons for social medicine’s mid-century ebb before its revival around 1970. By exploring the contributions of a range of actors, taking seriously the genealogy of ideas and ideology, critically evaluating European origin stories, and being attentive to broader political, geopolitical, and scientific contexts, I present a new perspective on the history of LASM.

The First Wave: From Hygiene to Socialized Medicine

Social medicine’s first wave emerged from broader discourses on the so-called social question, a confrontation with the changes resulting from rapid capitalist modernization in some Latin American countries. Situated between traditional, conservative elites, on the one hand, and the more radical proposals of movements like anarchism, anarcho-syndicalism, and socialism, the positivist intellectuals drawn to the social question settled largely for a middle way: gradual political reform to channel the demands of the working class, along with social policies meant to improve living standards and mitigate the worst excesses of capitalist development. Under the sway of Comtean positivism, Latin American health reformers saw society as malleable and manageable through the application of scientific knowledge. Reformers also drew occasionally on the notion of “social justice” from Catholic social doctrine, which was essentially the church’s doctrinal reckoning with the social question. Major ideological formations of the era – socialism, anarchism, liberalism – do not map neatly on to different types of social medicine. Rather, we find that social medicine blended, eclectically, ideas that may seem ideologically incompatible, as Dorothy Porter suggested.Footnote 16

Social medicine’s advocates were also fully immersed in the tenets of higienismo, the hygiene movement. In a sense, social medicine was a potent expression of the hygiene movement’s conviction that society’s ills could be managed with the analytical tools of medical science backed by strong states. As Foucault argued in his 1970s essay “The Birth of Social Medicine,” the field was not “anti-medicine” but rather it intensified the medicalization of social problems, as developmental states became concerned with the environmental conditions of cities and the productivity of human capital.Footnote 17 Social medicine extended the domain of hygienism, as infectious disease epidemics began to wane while chronic, entrenched problems, from alcoholism to malnutrition to child mortality, became more visible. In Latin America, social medicine as an elevated form of higienismo was personified in experts like Carlos Enrique Paz Soldán in Peru, Germinal Rodriguez and Ramón Carrillo in Argentina, or Luis Morquio in Uruguay, who often worked in narrower domains like puericulture, sexual hygiene, occupational medicine, nutrition, and rural medicine. They thrived in an era of Latin American “political doctors,” liberal scientific modernizers with an often-highhanded view on the working class.

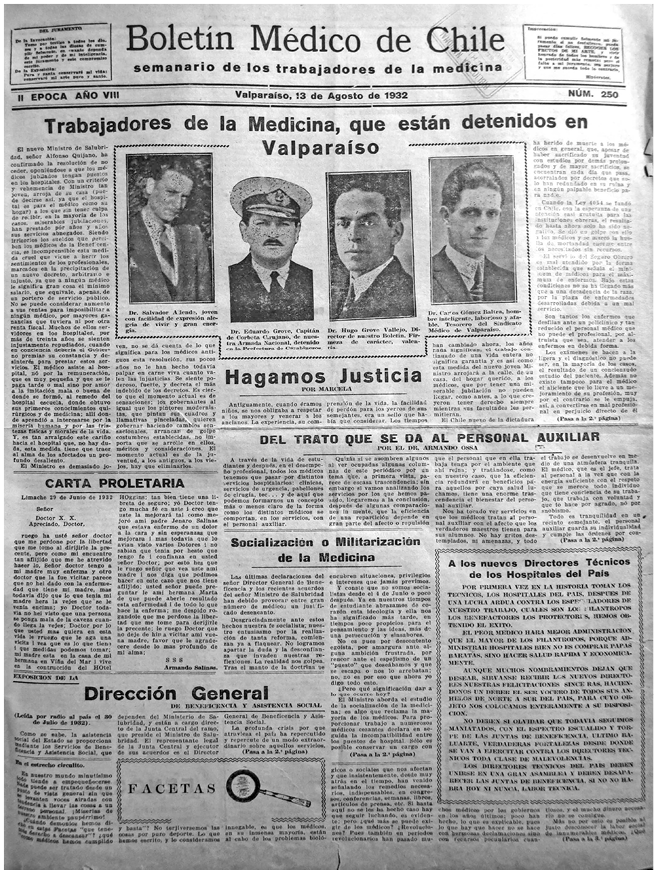

Nowhere in Latin America were medical professionals so engaged politically as in Chile, where social medicine was prominent during an eventful, sometimes turbulent period in the country’s political history. Around the end of the First World War, anarchists (or libertarian socialists), such as physician and writer Juan Gandulfo, questioned the necessity of the state and sought to help the working class emancipate itself through grassroots consciousness-raising and health promotion. Progressive physicians, who channeled Gandulfo’s radical energy more than his policy ideas, attempted to organize as Chile’s first medical labor union, the Sindicato de Médicos, founded in 1924 in the anarcho-syndicalist hotbed of Valparaíso. This union was short-lived but other medical labor organizing followed, in the form of the Vanguardia Médica (Medical Vanguard), aligned with the Chilean Socialist Party, which laid the foundations for the AMECH, the Chilean Medical Association (Figure 3.1). Doctors organized primarily to defend their professional interests and prerogatives within a new social insurance system – the Caja del Seguro Obrero, or CSO – and to avoid being reduced to “mere functionaries” within a large government bureaucracy. But labor organizing in medicine became fractious since there were many competing objectives: maintaining professional autonomy, regulating the practice of medicine, protecting workplace conditions, engaging the political system directly (in elections and legislation), and improving health conditions for all Chileans.

Figure 3.1 Front page of the Boletín Médico de Chile, the voice of the Vanguardia Médica, August 13, 1932. This story reports the detention of Salvador Allende (then 24 years old, at left) and other left-wing figures, including doctors and health workers, during a chaotic period known as the “Socialist Republic of Chile.”

While the social medicine movement was accelerated by leftist political figures, it was not an exclusively socialist project. Salvador Allende, who would prove to be the most famous member of the Vanguardia Médica, attempted to align social medicine with the goals of his Socialist Party. Like Gandulfo, the anarchist doctor, Allende’s political career began with organizing students at the University of Chile, coordinating with labor unions and other groups to hold anti-government protests and general strikes. Meanwhile, in a parallel stream within social medicine, a group of relatively conservative doctors influenced by Catholic social doctrine, led by Eduardo Cruz-Coke, worked to improve health conditions through such measures as the Law of Preventive Medicine and the establishment of the National Council on Nutrition. From 1937 to 1942, first Cruz-Coke and then Allende took turns as ministers of health under different governments, using this power effectively to strengthen health policy.Footnote 18 Soon after starting his term as Minister of Health, Allende wrote the report La realidad médico-social chilena, which later attracted the attention of Waitzkin and other chroniclers of social medicine’s history.Footnote 19 While Allende and Cruz-Coke maintained amicable relations despite their political rivalry, leftist and conservative factions divided at the birth of AMECH, partly due to Allende’s insistence on placing the legalization of abortion on the agenda at the association’s first conference, in 1936, sparking a boycott by a group of doctors affiliated with the Catholic University of Chile, including Cruz-Coke.Footnote 20

The ideological diversity within Chilean social medicine helps to explain why, when the legislation that would eventually create Chile’s National Health Service (the SNS, or Servicio Nacional de Salud) was introduced to the national congress in 1950, many years after it was first proposed, representatives of almost every political party stood up to claim, legitimately, a role in constructing this national health system.Footnote 21 Despite often contentious disagreements, the parties converged in giving priority to social justice, the development of human capital, and the socialization of medicine. From the 1920s to the 1950s, Chilean social medicine was a fluid field of policy experiment, where participants drew inspiration from a hodgepodge of internationally available health policy options and worked to adapt them to their evaluation of Chilean realities. At the same time, as Maria Eliana Labra has argued, existing policy structures, especially the CSO, imposed a path-dependency that bounded the scope of reform proposals.Footnote 22

During this period, networks to support a stable international epistemic community in social medicine were weakly developed. Instead, there was a mix of influences from abroad to support national-level projects of health reform. Although there was no programmatic diffusion of social medicine thought from Europe to Latin America, it is true that the Geneva-based LNHO and ILO offered policy models like social insurance and some support for research into pressing public health issues, like malnutrition and infant mortality. European and North American expertise in such areas was often sought out and welcomed; for example, Allende would draw extensively from a 1935 survey of nutritional conditions in Chile, carried out by two European experts sponsored by the LNHO.Footnote 23 Though numerically insignificant and politically marginal at the time, the Latin American left wing – the Apristas and José Carlos Mariátegui of Peru, libertarian socialists, anarchists, and vanguard intellectuals – influenced social medicine, though the interests and preoccupations of medical doctors frequently failed to harmonize with those of the labor movement more broadly.Footnote 24 Sometimes there were cross-national policy transfers – as with Costa Rica’s “Caja” system of social insurance, which used the Chilean CSO as a blueprint – but mostly social medicine failed to coalesce in sustained institutional form across Latin America.

The Chilean experience from the 1920s to the creation of the SNS in the early 1950s demonstrates an irony of the politics of social medicine: namely, successful strengthening of the state’s health institutions tends to undermine social medicine’s role as a critical and integrative intellectual field. The Vanguardia Médica saw disease and illness as the end result of a web of causal factors, a fraying of the social fabric that lay mostly outside the domain of medicine. This exercise in causal analysis took political doctors beyond the space of the clinic – either in their mind’s eye or in their daily practices – into the slums, the conventillos, the rural shanties, and the northern mining towns. Confidence in the new SNS shifted attention to the narrower territory of the health system. The creation of the SNS was a success story for first-wave social medicine, but the old spark of subversive and revolutionary possibilities in social medicine mostly disappeared, supplanted by the concerns and routines of a new generation of health technocrats.

The Decline of Social Medicine in the Early Cold War

The first wave of Latin American social medicine crested in the late 1940s and over subsequent decades the field and its integrative, holistic, and socially conscious philosophy were marginalized in favor of other, seemingly more “modern” models for improving population health. Examining this time of relative dormancy in social medicine during the 1950s and 1960s, rather than diverting us from the main story, is actually crucial for sharpening our understanding of social medicine, what it meant, and how it was changing.

Social medicine in Latin America faded in this period for many reasons, but two factors must be emphasized. First, the medical profession, on the whole, became more conservative and suspicious of state involvement in the health sector. By the 1960s, concerned over the threat of communism (which, after Cuba’s revolution, no longer seemed abstract), doctors as an interest group began to push for greater autonomy from the state and sought distance from the often-chaotic realm of national politics. In Chile, the national medical union, the Colegio Médico, a descendant of the radical AMECH, increasingly acted as a bulwark against further centralization of health services under the SNS. In the early 1970s, the conservative Colegio Médico actively undermined the government of Allende – who had been the organization’s first leader – and threw its support behind Pinochet’s authoritarian regime.Footnote 25 In Argentina, the 1950s and 1960s witnessed doctors’ strikes, fragmentation of health insurance and delivery into entities known as obras sociales, resistance to the politicization of medical education, and a search for international prestige in medical specialties, all of which prevented the establishment of a centralized health system.

Another important factor was the growth of a powerful international development apparatus that incorporated new social science approaches which, in turn, crowded out social medicine ideas and praxis. The apparatus of modern health planning that developed during this period drew the energy of public health personnel inward, into specialized, professionalized fields, and away from an engagement in the larger political realm to advocate progressive social policies. New “functional international organizations,” such as the World Health Organization (WHO), Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), UNESCO, and the Food and Agricultural Organization, along with international financial institutions (World Bank, IMF, and Inter-American Development Bank), provided career opportunities for health professionals and new ways of thinking about progress through research and planning. Specialized research centers, like the Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, CEPAL) and Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (Latin American School of Social Sciences, FLACSO), both headquartered in Santiago, trained a generation of social scientists to analyze the workings of national societies according to paradigms (positivism, functionalism, behavioralism) that were broadly acceptable internationally and shaped the mindset of mainstream international development institutions, which in turn affected health policy priorities across the region.Footnote 26 The idealism, passionate rhetoric, and radical proposals of social medicine were thus at odds with the increasingly technocratic procedures of national health planning in the postwar era.

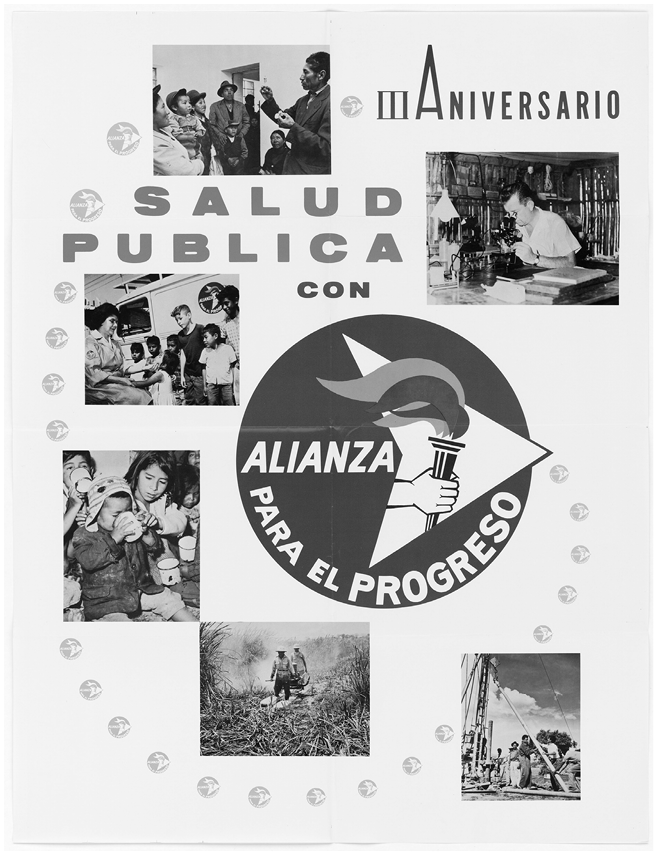

For progress in health policy, the new social sciences were a double-edged sword: robust research paradigms, and investment in social science research programs, helped to refine and improve health policy but at the same time, the emphasis on rational planning of interventions according to the economic possibilities of each nation tended to sideline concerns over equity and marginalize ideas of the political left. A new generation of pragmatic international technocrats came to power, tailoring their words and actions to the dominant development discourse of the era.Footnote 27 The Cold War geopolitical priorities of the United States, as the hemispheric hegemon, promoted this shift in mentality. The Alliance for Progress of the 1960s, as a counter to the Cuban Revolution, intensified US backing of development projects in Latin America (Figure 3.2). And what some have labeled “medical McCarthyism” spread from the US to restrain leftist involvement in health politics across the region (see Fonseca, Chapter 8 in this volume).

Figure 3.2 Alliance for Progress public health promotion poster. U.S. Information Agency. Bureau of Programs.

It would be a mistake to think that the international health and development technocracy was merely an imposition from the outside; Latin American experts embraced this new “development apparatus,” adapting to its norms and creating new possibilities within it. A collaboration between PAHO (Pan-American Health Organization, Organización Panamericana de la Salud, OPS), the CEPAL, and its affiliated economic research institution in Venezuela, the Centro de Estudios del Desarrollo (Center for Development Studies, CENDES), launched the influential OPS/CENDES health planning method, which trained over 5,000 health ministry bureaucrats from across the Latin America region.Footnote 28 Abraham Horwitz, a veteran of the Chilean SNS, who came to lead the PAHO from 1958 to 1974, embodied a pragmatic new approach, leveraging the resources of the new development apparatus (including funds from the Alliance for Progress) to create new professional opportunities for Latin American health workers, address persistent public health problems, and shield the health sector from the vicissitudes of national health politics. Benjamin Viel – like Horwitz, part of a nucleus of Chilean salubristas trained at Johns Hopkins’ school of public health – found ways to use the flow of development money (for family planning projects in the 1960s, for example), to continue community-oriented, proto-PHC projects within the SNS.Footnote 29 Such projects were grounded in the model of “preventive medicine,” which emphasized behavior modification to minimize health risks, while avoiding discussion of structural determinants of those risks.Footnote 30 Thanks to the influence of PAHO technical assistance, public health education in Argentina became increasingly professionalized and immersed in modernizationist theories of cultural change.Footnote 31

Thus, social medicine was temporarily displaced in the discourses of medicine, public health, and health planning during the early Cold War period. Its holism, appeals to diverse philosophical influences, incoherence as a scholarly field, and lack of a research agenda all marginalized social medicine in the realm of medical education, increasingly under the hegemony of the ideas of Abraham Flexner and his reforms of medical education in the US, starting at Johns Hopkins.Footnote 32 Meanwhile, in response to geopolitical pressures and following the technocratic development logic of the Cold War, the WHO turned its back on rights-based, horizontal approaches that required comprehensive, critical analysis of social inequalities.Footnote 33

As health system planners developed specialized expertise, they narrowed their scope of action and became more reductionist in their understanding of how to improve population health conditions. The growth of a postwar international development apparatus encouraged these habits of mind and ways of thinking; professional survival and advancement depended on incorporation into techno-bureaucratic systems. The successful figures in Latin American health of this era – people like Horwitz, or Viel – “stayed in their lanes” not just for the sake of professional self-preservation but also because it promised the best chance for success, which they defined as measurable improvement in population health outcomes. Meanwhile, radical voices from early social medicine, like Josué de Castro of Brazil, found themselves increasingly out of step with the times. Though his famous book The Geography of Hunger featuring holistic, integrative, and politically charged analysis of the social causes of hunger, malnutrition, and child mortality was widely read for a while, he was increasingly alienated from the centers of power of the international development apparatus and exiled from Brazil soon after the military took over the government in 1964.Footnote 34

Second Wave: A New Latin American Social Medicine

Disenchanted technocrats, not revolutionaries, would spark the second wave of Latin American social medicine in the 1970s. The political energy of the first wave of social medicine ebbed in the 1950s and 1960s, as international health institutions expanded and consolidated their power in a larger apparatus of modernization and development. As time went on, however, a small but influential faction of technical and administrative personnel in the international health and development apparatus grew disillusioned with ineffective bureaucratic routines and sterile, uncritical discourses about public health (including the field of “preventive medicine,” which had become a politically neutered variant of social medicine). The harshly repressive dictatorships of the 1970s imposed severe constraints on the budding new wave of LASM, but such political pressures also fostered movement solidarity.

The new social medicine emerged during a period of broader intellectual ferment in Latin America. Overall, these intellectual influences can be described as leftist, anti-authoritarian, and skeptical of Western modernity. While not exactly part of the international “counterculture,” the new generation of LASM was certainly stimulated by changing times, marked by decolonization, student protests, anti-war demonstrations, church reforms, new musical styles, and other signals of the disintegration of old orthodoxies and the crisis of modernity in the West. In the domain of development studies, dependency theory broke out of cepalino circles into the widely broadcast polemics of Andre Gunder Frank and Eduardo Galeano. Meanwhile, Paulo Freire, whose Pedagogy of the Oppressed was published in Brazil in 1968, explained how Western education tended to reproduce oppressive and hierarchical social structures. Che Guevara was an indirect but potent influence on social medicine for his ideas of the communist “new man” and the “revolutionary doctor” but more importantly, as a model for turning ideology into decisive, radical action.Footnote 35 Older Marxist intellectuals, from Marx and Engels, to Gramsci and Mariátegui, were rediscovered, reread, and incorporated into the canon of university courses in politics and sociology in Latin America.Footnote 36 The political climate of the time, marked by the Cuban Revolution, student protests in Mexico in 1968, and the violent overthrow of Allende’s government in 1973, added urgency to social medicine debates, and created the conditions for the formation of a core group of social medicine theorists in exile.

It was disaffected health technocrats who brought such social theory into conversations about medical education and health policy while also building the networks that would coalesce in the new wave of social medicine. In particular, the Argentinean Juan César García coordinated, sometimes covertly, the activity taking place in nodes of new social medicine thought. García skillfully leveraged his high-level position in PAHO’s department of medical education to spread new ideas and, just as importantly, connect health workers across the hemisphere who were interested in critique of conventional health planning and more radical theories of social change. Mario Testa, a leader of the OPS/CENDES health planning program in the 1960s, became a fierce critic of such technocratic efforts. Health planning, he now argued, not only failed on its own terms, but also depoliticized the underlying problem of social inequality. For much the same reason, Sérgio Arouca took aim at conventional preventive medicine programs in Brazil.Footnote 37 Extending this critique, Francisco de Assis Machado, along with Arouca, Testa, and others, attempted to enact a new model of community-organized healthcare in the Montes Claros project, in the state of Minas Gerais.Footnote 38

Social medicine’s resurgence came amidst the brutality of dictatorship, and the experience of repression and exile forced the leftist-progressive group of Latin American doctors, health workers, and health social scientists to band together. From the mid-1960s until the mid-1980s, Argentina, Chile, and Brazil were under authoritarian governments for extended periods. Exiles from Argentina (such as Testa, José Carlos Escudero, and Hugo Mercer) and Chile (including numerous officials of the Ministry of Health or staff of the School of Public Health in Santiago during Allende’s ill-fated government, like Gustavo Molina Guzmán or Clara Fassler), found safe harbor in universities, hospitals, and health projects in other Latin American countries, the US, and Europe. Under more open political conditions, the ideas of the new social medicine might have been assimilated, as in the earlier period, into the structures of national welfare states and international health bureaucracies – tamed, so to speak. But in the 1970s, the group of leftist health workers in exile was too large and too unorthodox ideologically to be digested into the machinery of official international development. Instead, they formed a new identity as a cohesive outsider group through their far-flung networks.

The “second wave” of LASM was distinctive from what came before for many reasons, first among them a serious consideration of social theory. During social medicine’s first wave, the social sciences as systematic disciplines were hardly known in Latin American universities. Thus, members of the early social medicine milieu were mostly medical doctors who employed eclectic conceptual frames that drew inspiration from natural sciences (positivism, eugenics, hygienism), along with Catholic social doctrine and medical humanism. By contrast, in the 1970s, new theoretical currents from the social sciences, including structural Marxism, feminism, post-structuralism, and post-colonialism, reinvigorated social medicine thought. The new generation in social medicine mobilized such theory to take on functionalism, positivism, behavioralism, and developmentalism (desarrollismo), which were the intellectual and ideological pillars of the international health and development apparatus. Though many in the second wave of social medicine were trained in medicine, scholars like Eduardo Menéndez, Susana Belmartino, and Maria Cecília Donnangelo were not health professionals but social scientists who trained their critical lenses on medicine as a socially powerful institution.Footnote 39

The new wave of social medicine coincided with growing suspicion of Western medicine. In Brazil, living under a military regime sharpened the saúde coletiva group’s critical portrayal of medicine as an institution of discipline, punishment, and social control. This perspective was informed by influences from abroad, such as the pioneering work of Michel Foucault (in books like Discipline and Punish or The Birth of the Clinic, which found a receptive audience in Brazilian academia – see de Camargo, Chapter 11 in this volume); the Italian mental health reform movement led by Franco Basaglia in the 1960s; and the critical humanism of Ivan Illich, the firebrand Catholic priest based in Cuernavaca, Mexico, whose book Medical Nemesis offered a polemical takedown of the medical establishment.Footnote 40 Illich was also part of the Liberation Theology movement, which had an important, though sometimes latent, influence on the integration of a social justice vision into Latin American health systems. Most academics in social medicine avoided overt discussion of religion but coalition-building with ecclesiastical base communities (comunidades eclesiais de base) and Catholic charity groups was a crucial part of the long process of Brazilian health systems reform.

These new endeavors sought not only to improve population health, but also to change the prevailing style of learning that characterized international development work. This style of learning depended on the top-down transmission of models created by experts in specific domains, so that most health planners hardly understood their models and analytic procedures well enough to offer cogent critiques or adjust them to local circumstances. And yet, nearly all the institutions and projects central to the new social medicine – graduate programs in Mexico and Brazil, the Cuenca meetings, Educación Médica y Salud, the Montes Claros project – received funding and support from PAHO, USAID, or the US-based Kellogg Foundation. As a whole, the network placed more value on the open exchange of ideas and information, and the maintenance of protective friendships, than the enforcement of any one ideological party line. Thus, the many social medicine journals created in that decade – Saúde em Debate, Salud Problema, International Journal of Health Services, Cuadernos Médicos Sociales (of Rosario, Argentina) – aired theory from many different quarters, usually leftist but drawing from the many varieties of Marxist theory, post-structuralism, feminism, and phenomenology.Footnote 41 More broadly, we could say that LASM became a part of the international civil society milieu that developed starting in the late 1960s, from pro-democracy movements to human rights organizations like Amnesty International that put pressure on military dictatorships, international financial institutions, and multinational corporations. Eventually, soon after Juan Cesar García’s untimely death in 1984, and coinciding with the slow return to democracy in the region, these networks coalesced in the formation of ALAMES, an international association of professionals in social medicine.

Conclusions

Social medicine began as an offshoot of the hygiene movement, especially as public health policy concerns began to move away from infectious disease and sanitation, into more chronic population health issues, during the construction of Latin American welfare states. The first wave of social medicine, with its integrative, systemic, and holistic perspective, was helped along by support from international players like the League of Nations and ILO, although they were less important than networks of hygienists and health and social policy experts within Latin America. During the early Cold War period, social medicine faded internationally and in Latin America. A growing international health and development apparatus promoted narrow, specific projects and avoided contentious political questions. Social medicine seemed a relic alongside more scientific and supposedly apolitical approaches like health systems planning, preventive medicine, and disease eradication campaigns. But, disaffected technocrats within this larger apparatus proved to be the nucleus for the second wave of social medicine in Latin America in the early 1970s. The authoritarian regimes of the 1970s sent Chilean, Argentinean, and Brazilian health workers into exile, and they formed solidarity networks, programs of study in social medicine, new journals, and, eventually, international associations like ALAMES. The second wave of social medicine (in Brazil, collective health) led directly to major health systems reform in Brazil; offered imaginative ways of thinking about health, disease, and society; resisted the incursions of neoliberalism in the health sector; and shaped health policy of “Pink Tide” governments of the region, like Venezuela under Hugo Chavez, after the year 2000.Footnote 42

From this analysis, I draw three major lessons, which might inform not only the historiography on health and medicine in Latin America, but also affect the way we understand social medicine’s relationship to health systems in dynamic societies. First, we should be careful about linking LASM with European and North American intellectual and political movements. Certainly, there were influences on LASM from outside the region, but contrary to Virchow-centric histories, LASM was never in a state of ideological or intellectual dependency on European social medicine. Characteristically, LASM activist-academics have been engaged in deep analysis of national problems and connected in regional-scale (Latin American) expert networks. Such networks help to develop a geographical imaginary, a consciousness of Latin Americanism within (and against) the international economic and geopolitical order.Footnote 43 LASM has been fueled by homegrown or autochthonous social theories, whether dependency theory, liberation theology, or Freire’s critical theories of education, or the buen vivir philosophy more recently. In this way, LASM is part of a larger trend of constructing an “alternative” and “decolonial” epistemology of health, from the Global South.Footnote 44 As part of this larger effort, argues Mexican anthropologist Paola Sesia, Latin American social medicine needs accurate and complete histories of its origins and development, to “counteract the epistemic injustice” of hegemonic, Eurocentric historical narratives of the field.Footnote 45

Second, the history of LASM must be placed in the history of the social sciences in Latin America. In the early 1900s, the pioneers of LASM used eclectic analytical frames mixing social and natural sciences to analyze the roots of public health problems. As LASM matured, starting in the early 1970s, we see the development and influence of Marxist and poststructural theories that offered critical analytical tools to understand the role of health institutions in reproducing inequitable political-economic systems and cultural norms. Moreover, the professionalization and rising prestige of social scientists, especially sociologists, anthropologists, and historians, means that social medicine (and saúde coletiva), as an academic field, has considerable autonomy from the biomedical mainstream. While recent work like Margarita Fajardo’s The World That Latin America Created, on the CEPAL and the complicated rise of dependency theory in development economics, represent tremendous progress, the historiography of the social sciences in the region is still in its infancy, as compared to the much deeper explorations of histories of natural sciences, medicine, and public health.Footnote 46

Lastly, social medicine’s influence on health policy must be understood dialectically. Social medicine promotes often radical transformation of the health sector. However, successful reforms produce technocratic institutions to implement and manage more equitable and far-reaching health policies (like primary healthcare). This institutionalization inevitably defuses the radical outsider spirit of social medicine. And while LASM has empowered the medical community, physicians’ own professional and class interests often diverge, eventually, from a progressive health agenda. In this long-term dialectic process, militancy leads to policy achievements, which lead to institutionalization – a narrowing of focus and concentration of effort along technical lines. When the institutions are thrown into crisis, or fail to respond to the new demands of organized sectors, disillusionment and critique rise and may initiate new cycles of activism. When we think of social medicine dialectically – as a field of radical critique, interacting with the mainstream – we see that this relationship is laden with contradictions that keep social medicine from ever becoming the dominant principle or perspective in health politics.

From the 1920s to today, social medicine changes in response to dynamic political conditions and academic innovations. Like an organism that evolves in response to changes in the environment around it, social medicine has shed certain values, concepts, and associations (eugenics, medical paternalism, hygienicist moralizing) while gaining new ones (more sophisticated social theories, flattening hierarchies in the health field, stronger connections to other social movements, a commitment to participatory democracy). Despite its internal diversity and fluctuations in broader influence, social medicine nonetheless remains recognizable and consistent over the long run, with its critical perspectives on mainstream medicine, commitment to health equity, and advocacy for strong state involvement in the health sector.