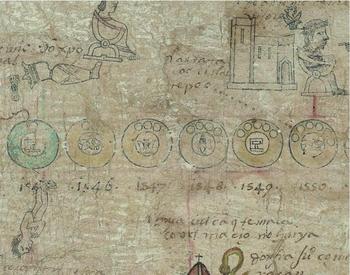

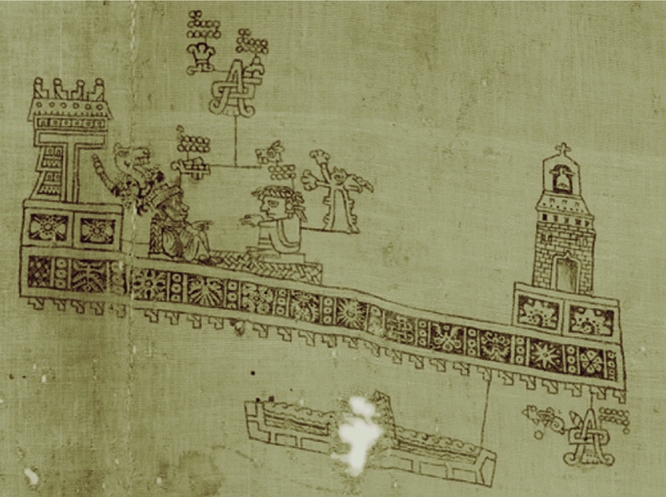

Around the year 1550, an indigenous tlacuilo (painter-scribe-historian) in Tepechpan, a small altepetl north of Mexico City, narrated the tumultuous events through which he had lived. In Figure 1, we see an excerpt of this tlacuilo's contribution to the town's annals, the Tira de Tepechpan, which depicts a sequence of events from 1545 to 1549. On the left, beneath the glyph for the year 1545, the tlacuilo paints a dangling corpse, its arms crossed and eyes shut, with blood spurting from the nose and mouth. Here the tlacuilo is telling us of the 1545 hueycocolixtli, the “great sickness” that killed at least a third of the population, according to conservative estimates. Among the victims was Tepechpan's ruler, the crowned figure wrapped in funeral cloth above the year glyph.

Figure 1 Excerpt from the Tira de Tepechpan, Made by Tlacuilos, Sixteenth Century

To the right of the ruler, however, the tlacuilo tells quite a different story for the year 1549. Here he paints a stone church with a fine gothic portal and bell tower, atop what appears to be a pre-Hispanic platform. The glyph marks the construction of a new stone church.Footnote 1 The contrast here, between mass death and monumental construction, is jarring. In the stark visual language of Mexican codices, the tlacuilo seems to be telling us that despite losing much of its population, Tepechpan still persisted in a building program that was as costly as it was ambitious.

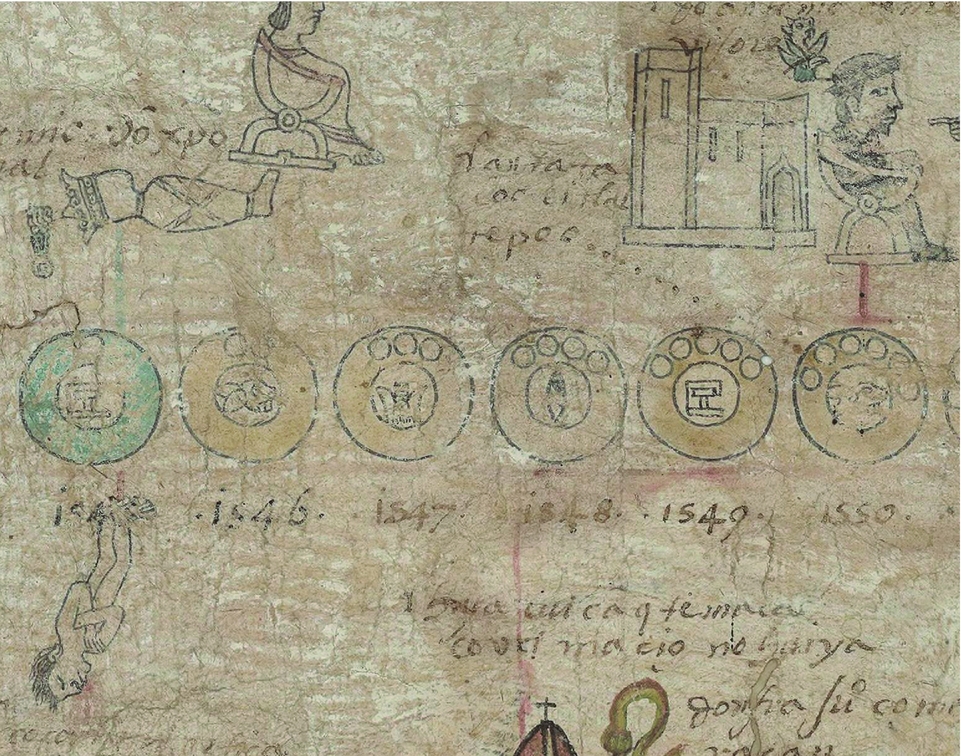

As in Tepechpan, so it was throughout central Mexico: From the Río Pánuco in the north to Oaxaca in the south, indigenous communities of different ethnicities and varying economic circumstances replaced their churches of thatch and wood with stone churches and monasteries. Laborers covered mass graves and then dug open quarries; they razed forests, hauled lumber, and burned lime; they assembled scaffolds and raised immense walls of stone; they set delicately carved limestone into gothic arches that soared into the heavens. Between the 1530s and 1580s, in the wake of demographic catastrophe, indigenous communities built 251 church-and-monastery complexes. Many of these structures still loom today over provincial cities, bustling country towns, and sparsely populated villages. As if defying their dire circumstances, indigenous communities built some of the largest edifices ever raised in colonial Mexico— in the shadow of mass death.Footnote 2 Figure 2 shows an example, from Yanhuitlán, Oaxaca.

Figure 2 Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo, Yanhuitlán, Oaxaca

Apart from their large scale, these complexes stood out from other colonial churches in two key ways. First, since they served as logistical and liturgical hubs in the mendicants' mission system, these structures were ostentatious markers of doctrina (mission head-town) status. Missionaries resided here and carried out their administrative duties. (Lower-ranked visitas, “visitation-missions” in outlying towns, were the spokes in this schema.) Second, in terms of indigenous politics, these complexes served as the core of political and religious life in local polities, and as such they confirmed the preeminence of the doctrina's immediate community over the surrounding sujetos, politically subservient subject-towns that tended also to be visitas. Given the elevated status that these monasteries conferred on the towns that built them, I refer to these complexes as doctrina monasteries.Footnote 3 This monumental mission architecture went on to influence subsequent mission building, most notably in the Philippines.Footnote 4

Because these voluminous and mysterious structures rose in the first decades of colonization, the travelers and scholars who have stumbled upon them have long assumed that their walls had quite a story to tell. Generations of scholars have combed these structures, parsing their façades, mural paintings, and architectural layouts for clues about the cultural encounters between natives and Europeans. Most studies have sought looked at these buildings, in their completeness, and tried to trace their origins to medieval and Renaissance Europe or to preconquest Mesoamerica.Footnote 5 Early scholars saw the large scale and widespread diffusion of these monasteries as indices of the completeness of the Spanish conquest. George Kubler's classic study, for example, attributes the rapid emergence of these stone complexes to the friars' “remarkable feats of moral persuasion,” which apparently sufficed to make entire communities move stone and lumber for two decades.Footnote 6 Subsequent architectural studies have taken a more nuanced approach, tracing the circulation and reach of European styles, architects, technologies, and iconography.Footnote 7 Meanwhile, over the past several decades indigenistas have issued their riposte to studies of European expansion: for them, the presence of indigenous elements—from the overall spatial layout of the complexes down to the detail of an indigenous town-glyph tucked away in a cloister in Cuauhtinchán—serve as tangible evidence of native agency. A structure that at first seems to be easily identifiable as European thus becomes, on closer examination, also a product of Mesoamerica.Footnote 8 What was once a symbol of conquest has effectively transmuted into a sign of indigenous endurance—into a new teocalli, or temple.

While the visible evidence etched into these walls has yielded telling discoveries, the social production of these edifices—the very processes involved in their construction—is far less visible in the completed buildings, and therefore remain largely neglected.Footnote 9 As in the Tepechpan tlacuilo's painted narrative in Figure 1, most histories have the large stone church simply appearing complete, ex nihilo. The church serves as evidence only in its completed, visually accessible form—it is significant only when finished. Yet the Tepechpan tlacuilo of Figure 1, a historian in his own right, has left us with a silence so great it raises a question. Returning to the image, one must note the void between mass death in 1545 and the completion of the stone church in 1549. Those unmarked years were undoubtedly full of both grieving and hauling heavy loads, of rebuilding lives and laying stone upon stone into the thick walls of naves and cloisters. What motivated these communities to undertake the great and costly endeavor of stone church construction at such a dire moment?

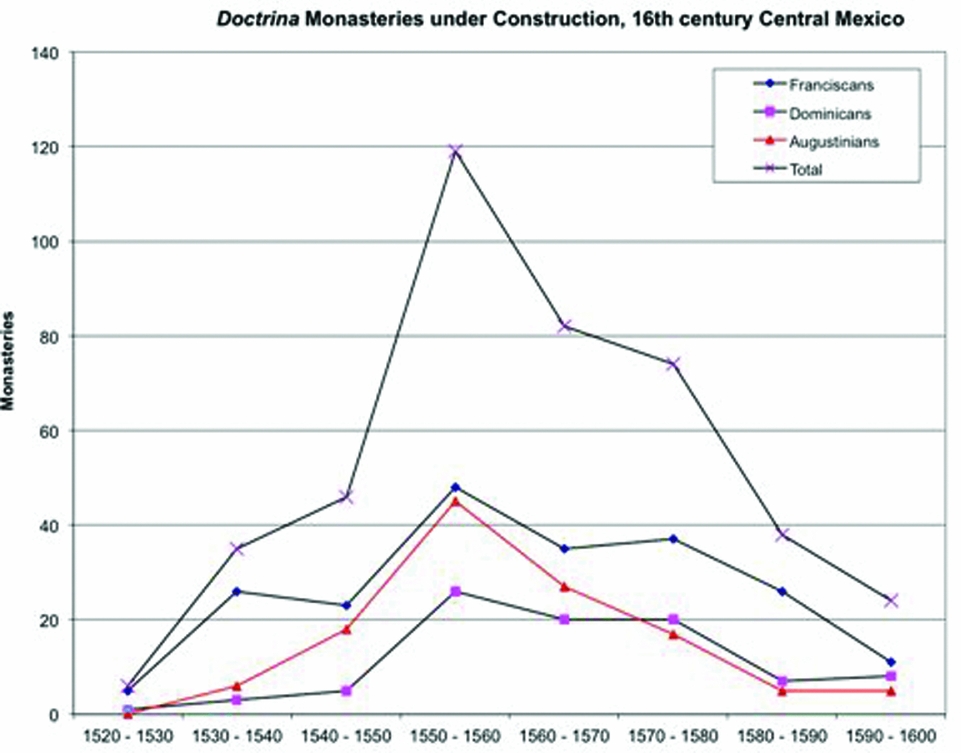

In the history of the region as a whole, the same silence hangs over the years between the mid-century demographic crisis and the completion of the doctrina monastery complexes not long thereafter. This is even more important because previously unexamined archival records demonstrate that this gap was not one of decades, as had been previously assumed, but of years—just as it is portrayed in the Tira de Tepechpan. Previous mission scholarship had tracked building campaigns solely in published mendicant sources and concluded that monastery construction peaked in the 1570s. However, having scoured thousands of viceregal records at the Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico City and the Archivo General de Indias in Seville—account ledgers, building licenses, procurement orders, and labor mobilization decrees—I have found that monastery construction campaigns in central Mexico actually peaked two decades earlier, in the 1550s, as shown in Figure 3.Footnote 10

Figure 3 Doctrina Monasteries under Construction in Central Mexico

Thus, the pattern of monastery construction throughout central Mexico is similar to the rapid (but as yet unexplained) turnaround in the tlacuilo's painting: after losing at least a third of their population, precisely when one might assume that building activity would stall or even cease, 119 towns instead commenced or continued building.Footnote 11 In turn, each of these projects affected dozens of outlying sujetos, or subject-towns. An endeavor of such magnitude, on the heels of catastrophe, evinces a region-wide movement that must be understood in sociopolitical terms. Why did hundreds of indigenous communities mobilize vast amounts of human labor, tributes, and natural resources to build on such an enormous scale? What impetus—what political and social forces—drove them to participate in these building campaigns?

To explore these questions, this article examines the social and political contingencies that were involved in the production of these immense structures. Mendicant expansion and rivalry, as mission scholarship has long noted, presented a demand for missionary infrastructure, but each newly founded doctrina depended on the imperatives of local politics. When placed in their immediate context, the construction campaigns are inextricable from native rulers' efforts to reconstitute their polities during the volatile years after the hueycocolixtli. As depopulation intensified territorial conflicts and strained local hierarchies, monastery construction served as a conspicuous means to reassert power over lands and people. Like a chameleon—or a nahual, the shape-shifting sorcerers of Mesoamerican religions—the doctrina monastery constantly shifted its attributes: at one moment it functioned as a colonial mission, at the next, it rematerialized as a teocalli. While these structures bolstered Spanish claims to sovereignty over New Spain and established an infrastructure for missionaries, they also reasserted local indigenous claims to sovereignty in ways uncannily similar in practice to the preconquest Mesoamerican teocallis. Yet, precisely because of this political importance in both indigenous and Spanish colonial contexts, these structures were also battlegrounds in struggles over lands and labor. Far from being the products of a community-wide consensus, as scholars have generally assumed, these costly projects involved constant negotiation, contestation, and resistance. In the shadow of death, each stone laid into these vast structures both reflected and remade a fragile and contested social order.

The Hueycocolixtli

The principal catalyst behind the accelerated monastery building campaigns was the far-reaching demographic catastrophe that swept Mexico in the 1540s. The calamity, especially the social and political disruptions that it caused, made the construction of the doctrina monasteries seem urgent and necessary to indigenous rulers. In the spring of 1545, a devastating epidemic, known as the hueycocolixtli or “great sickness,” struck several indigenous towns surrounding Mexico City and over the next months spread across the length and breadth of central Mexico.Footnote 12 This was the second of three major abrupt crashes in the sixteenth-century indigenous population of New Spain. The epidemic cut apart native ruling hierarchies, it decimated families, and it reduced rural populations to such an extent that the countryside—the densely populated lands vividly portrayed in conquistadors' reports—now appeared to Spaniards to be only irregularly settled.Footnote 13

Native and Spanish histories note the same symptoms and social effects: the onset of fever followed by blood flowing from the orifices, the indiscriminate way that the disease struck lords and commoners alike, and the cruel indignity of mass burials.Footnote 14 Although some Spaniards also fell ill, typhus was generally endemic to Western Europeans—potentially fatal, but not catastrophically so for society at large. Thus Spanish colonists went relatively unscathed while millions of indigenous people died.Footnote 15 A passage from the Anales de Tecamachalco conveys the horrific reach and suddenness of the catastrophe:

1545. In this year occurred the hueycocolixtli. Blood came out of peoples' mouths, their noses, and through their teeth. It came here during planting season, in May. The mortality was terrifying; at the beginning of the epidemic they would bury ten, then fifteen, twenty, thirty, forty in one day. And many children died over the course of a year until the sickness was over. Then the nobles [pipiltin] died, the one who was hueyteuctli [great lord], and other lords.Footnote 16

Nothing—not prayers to gods old or new, nor medicinal remedies—could stop the dying.Footnote 17 For almost two years the disease raged, straining communities' abilities to produce food and care for the sick. Famine soon followed. The escalating mortality quickly overwhelmed communities' abilities to bury the dead. With great alarm, missionaries and royal officials sought to quantify the losses and warned that the indigenous population was in danger of disappearing like that of the Caribbean. Spanish observers resorted to conveying the magnitude of the catastrophe in biblical proportions. Archbishop Zumárraga estimated the population loss at one-third, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún at half, and Fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinía placed the losses as high as two-thirds. Fray Domingo de Betanzos, meanwhile, estimated that “not a tenth remains of the population that there was here twenty years ago.”Footnote 18 These contemporary estimates do not differ greatly from those of modern historical demographers. After the Berkeley historians Sherburne F. Cook and Woodrow Borah projected mid-century losses at a staggering 80 percent, subsequent revisionists lowered estimated losses to a “moderate” 62.5 percent and a “mild” 31.5 percent.Footnote 19 Thus, even the most conservative estimates point to a demographic catastrophe.Footnote 20 In 1554, Motolinía stated the only certainty: “Many, many people are missing.”Footnote 21

By the time the survivors covered the last mass graves in 1547, the hueycocolixtli had already begun to transform the social and political landscape of central Mexico. Disease and death had moved unevenly across the land, altering rural patterns of settlement, reshuffling territorial arrangements among rival polities and destabilizing local hierarchies. Mesoamerican local states tended to integrate agricultural and urban settlement more evenly than the European centers. Outside the complexes of stone buildings that housed the teocalli, tecpan (ruler's palace), and tianquiztli (market), indigenous towns seamlessly blended into a landscape dotted with hamlets among milpas (corn plots) and terraces.Footnote 22 After the hueycocolixtli this landscape lay devastated. Indigenous and Spanish authorities noted that famished refugees were fleeing decimated communities and roaming the countryside. Former cabeceras (semiautonomous head-towns) like Teteoc near Chimalhuacan, or Yucanuma in Oaxaca, disappeared entirely from the tribute lists. The landscape, once “full of people,” was now eerily “empty.” Hillside terracing, another sign of dense population and labor-intensive agriculture, ceased as survivors moved down to valley floors to cultivate in abandoned fields. Crop failures and famines further destabilized community economies.Footnote 23

The colonial relations between Spanish and indigenous communities only magnified these disruptions. In a letter to Prince Philip in 1547, Archbishop Zumárraga wrote that communities that had already been struggling to feed themselves under onerous Spanish demands were now stretched beyond capacity. With tribute and labor schedules still fixed according to the pre-hueycocolixtli population, the survivors bore an increasingly heavy burden. When a royal commissioner inquired into the tributes paid by the town of Azoyú (Guerrero), for example, the inhabitants bluntly stated that “the tribute was too heavy because many people have died.”Footnote 24

Spanish colonists were not immune to the deepening economic crisis. Construction projects like Archbishop Zumárraga's cathedral in Mexico City stalled. Zumárraga declared that the emergency made reducing tribute and labor burdens an imperative, even for his cathedral. To rely on native labor in these grim circumstances, he confessed, would be rather like adding “Indian blood to the mortar mixture” for the cathedral walls.Footnote 25 Ironically, as he penned those very lines, the survivors were mixing mortar for structures of unprecedented size in their own communities: the doctrina monasteries.

Building a New Teocalli

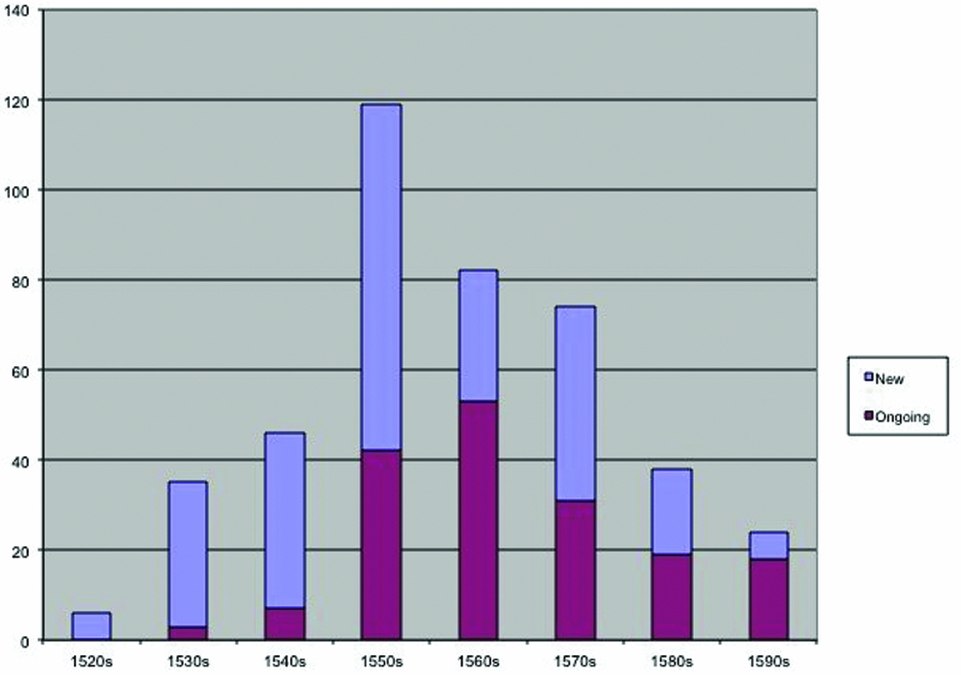

It would be entirely reasonable to assume that while indigenous communities strained to recover, feed themselves, and work for Spaniards in the aftermath of the hueycocolixtli, they would have avoided building edifices whose design had no precedent in Mesoamerica. Construction projects depended on the availability of obligatory commoner labor, and the loss of a third of the population entailed an equivalent reduction of the available labor pool. Yet build they did. In Tepechpan, the hueycocolixtli had devastated the community: testimonies in 1550 reported that famished survivors were fleeing, missionaries could barely be fed, and in light of their predicament local rulers were seeking to reduce their tributes to Spaniards. Even so, construction of the local church continued. Indeed, the local rulers sued their claimed sujetos, taking their case all the way to the Council of the Indies in Seville in order to compel them to provide labor for church construction.Footnote 26 Similar stories abound across the rest of New Spain. In the wake of the hueycocolixtli, at least 80 communities across New Spain initiated these costly building campaigns, while other projects already under way proceeded apace. As can be seen in Figure 4, 46 monasteries were under construction in the 1540s, of which 38 were projects initiated in that decade. At least seven of those projects were begun during or after the hueycocolixtli.Footnote 27 In the 1550s, this number soared to 119 projects. Of these, 77—some 65 percent of the total—were new projects begun in that decade. In 1550 alone, just three years after the hueycocolixtli abated, Viceroy Luis de Velasco approved 20 proposals for new monasteries.Footnote 28 All this activity amounted to a colossal marshaling of human energies, a unique movement that, for three decades, defied the grim realities of demographic crisis.

Figure 4 New and Ongoing Monastery Construction Projects by Decade, Central Mexico, Sixteenth Century

Only a handful of scholars have addressed the relation between mid-century monastery construction and demographic crisis. George Kubler, and later Adrian Van Oss, posited that construction campaigns redoubled due to an allegedly robust demographic recovery—a claim that historical demography has negated entirely.Footnote 29 More recently, Eleanor Wake has addressed the demographic question from an indigenous perspective, arguing that an “ecstatic” indigenous religiosity in the wake of the hueycocolixtli drove these construction campaigns. Wake holds that the construction campaign can be reduced to one overarching motive: “ritual and image as the basis of religious expression.” According to this view, having suffered demographic losses, indigenous populations concurred that they needed new ritual centers in order to maintain their “traditional native religious practices.”Footnote 30 Wake describes sixteenth-century native religiosity as a nearly unaltered form of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican spirituality, and narrowly defines native religion in terms of ritual and cosmovision. According to this view, native religion was impervious to demographic crises and the ever-sharper asymmetry of colonial power relations. Consequently, the doctrina monastery was a manifestation of this deep and unchanging native spirituality, not of the colonial world around it.Footnote 31 This argument, however, separates native spirituality from material factors and historical contingency. Politics and spirituality were in fact always deeply intertwined, even entangled, in indigenous communities, and the spiritual and ritual elements of doctrina monasteries were susceptible to political calculations, material interests, and power plays.Footnote 32 Raising a teocalli or a doctrina monastery was a grand act of world-making in the broadest sense: at once it established a new spiritual home, and it reconstituted and empowered the political and economic networks that were connected to it. It materialized the sacred and sacralized worldly power, and in so doing it asserted the endurance of the community.Footnote 33

Although the demographic crisis was not a propitious time to build on a grand scale, its disruptions also made obvious the need to inscribe power relations into stone. The mid-century crisis had sown chaos into an already turbulent indigenous political world: it intensified the territorial struggles that the fall of the Aztec Empire had unleashed nearly three decades earlier, and it destabilized already brittle social hierarchies. Indigenous polities were organized in a cellular fashion. Within each local state (altepetl), constituent sub-units (calpulli) retained their territorial integrity, local hereditary rulers, temple, and control over local resources and labor. These sub-units ranged in size from hamlets to small cities. Although they formed part of the larger local state, each enjoyed a degree of semi-autonomy. Local polities were therefore a conglomeration of smaller statelets, each with ambitions and interests of its own. This cellular organization provided local communities with some flexibility to adapt to crises, but it also opened the way for factionalism and territorial fragmentation. Calpullis and altepetls weakened by war or depopulation could join to form regional powers, but ambitious sub-units that survived a crisis could just as easily opt to seek greater control over their own resources and labor either by asserting their power within the confederation, or by simply seceding from it. Thus, there was an inherent tension in Mesoamerican politics that was marked by “contrary tendencies of formation and separation.”Footnote 34 The doctrina monasteries were the results of this tension.

The hueycocolixtli crisis of the late 1540s only exacerbated these centripetal and centrifugal forces, due to the uneven manner in which the epidemic brought down some sub-units while sparing others. Not surprisingly, this opened up new opportunities for rulers in surviving units to seize power at their rivals' expense.Footnote 35 They did so by erecting churches. In Amecameca, for example, a long-running power struggle between two sibling noblemen who ruled over rival sub-units came to an end after one of the brothers died during the hueycocolixtli. The surviving brother, don Juan de Sandoval, proceeded to concentrate local power around his sub-unit by building an immense Dominican monastery. As he did so, don Juan subjected his deceased brother's calpulli to the new cabecera, the head-town of the reconstituted polity that emerged around his new doctrina monastery.Footnote 36 Similarly, across the devastated landscape of post-hueycocolixtli Mexico, local hierarchies harnessed the rebuilding efforts of the survivors and asserted (or reasserted) control over lands, tributes, and commoners' labor. They did what they had always done during crises: they remade Mesoamerica by maintaining, splitting, and fusing polities. Church construction, like temple construction before the conquest, was both a tool and a principal expression of the contrary forces that reconstructed local native states.

The struggles to assert local sovereignty are plainly visible in a variety of works commissioned by indigenous rulers in the mid sixteenth century. Recent studies of cartography, painted manuscripts, lienzos (painted cloths depicting royal lineages or territorial claims), and native histories have revealed efforts of their patrons, mostly local rulers, to retell the histories of their communities in a way that was advantageous to them. Even while they drew upon their own visual and symbolic systems, the native tlacuilos also appropriated European treatments of perspective, and Roman script. These hybrid manuscripts recounted the sacred foundation of the altepetl, documented the chain of lineages that had ruled over it and its constituent sub-units, and delineated the territorial limits of the polity.Footnote 37 The Tira de Tepechpan, the painted annals that opened this chapter, is a prime example of this effort to reframe history and retell it to strengthen the altepetl and its rulers against internal and external threats.Footnote 38 Similarly, in Cuauhtinchan (in present-day Puebla), a nobleman named don Alonso de Castañeda commissioned the monumental Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca, which exalted the sacred origins of his altepetl, and used this ancient prestige to legitimize claims over disputed lands with the neighboring rival altepetl of Tepeaca. Across central Mexico, native tlacuilos reframed the past in order to gain leverage over an uncertain future.Footnote 39 While the painted manuscripts of the tlacuilos drew boundaries around land claims and traced ancient lineages, the stone church also served to reaffirm a sense of place, history, and sociopolitical order in the central Mexican local state.Footnote 40

Local rulers did not hesitate to sponsor native painters and sculptors, who inscribed their historical narratives onto monastery walls, façades, fountains, and vaults.Footnote 41 In Cuauhtinchan, during the same years that the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca was written, native painters decorated the friars' cloister with the symbols of their altepetl: the eagle, the jaguar, and the holy red cave central to their origin myth (see Figure 5).Footnote 42 Thus, while some Spanish missionaries contentedly let themselves believe that by building “glorious churches . . . the Indians forgot the things of the past and the flower of their gentility,” indigenous communities appropriated this architecture for their own ends and made it embody their sacred histories.Footnote 43

Figure 5 Jaguar and Eagle Place-Glyphs Alongside the Annunciation of the Virgin, Monastery Cloister, Cuauhtinchan, Puebla

The new stone church filled the void left by the destroyed teocalli and took its place in the enduring grids of indigenous political power, spirituality, and identities. In many cases the overlay was literal. Tlaxcalan cabildo records, for example, simply refer to churches as teocallis.Footnote 44 Communities throughout New Spain, urged on by iconoclastic friars, built doctrina monasteries atop the platforms of their former teocallis.Footnote 45 Friars reveled in the material destruction of the teocalli, but for natives the very stones, sacred location, and power of the teocalli was invested in the new stone church. Indigenous histories depict the teocalli as the sacred site upon which the community was founded; it was a node between heaven and earth that linked the community to the otherworld and to the ancestral past.Footnote 46 Yet the teocalli, and the stone church that replaced it, also mirrored the social order of this world. Indigenous nobles and priests had legitimized and reaffirmed their authority by deploying commoner labor to adorn and maintain the teocalli, and the structure proudly proclaimed the altepetl's autonomy and territorial integrity to neighbors and imperial powers.Footnote 47 Long into the colonial period, the memory of a town's teocalli served as evidence of ancient autonomy in legal battles over jurisdiction.Footnote 48 Such memories were buttressed by emerging Christian temples. Rising in place of the teocalli, the new stone church absorbed its spiritual and political powers, making in the process a strong argument that the history, territorial integrity, and social order of the community would endure.

Striking evidence of this association of church and teocalli can be seen in indigenous visual representations. Scholars of indigenous art have traced a transition in manuscript painting in which the stone church emerged as a symbol of the pueblo itself in manuscript painting, accompanying—and sometimes replacing—indigenous hill-glyph symbols.Footnote 49 In the Mapa de Cuauhtinchan, a history-cartography of Cuauhtinchan produced in the mid sixteenth century, the core of the altepetl is represented by a hill-glyph symbol, the pre-Hispanic teocalli, and a symbol of the new doctrina monastery, with its cavernous church and atrio.Footnote 50 Symbols of churches also bolstered the claims to power of ruling lineages. In the images below, two local rulers, their status indicated by reed mats, are seated beside local churches to indicate their patronage. In Figure 6, from the Mixtec ñuu (indigenous polity) of Zacotepec in Oaxaca, a married couple of two hereditary rulers (yuhuitayu) are shown on their reed mats between a stone church, which sits atop a sacred platform, and a palace/temple.Footnote 51 In the image, the church symbolizes the polity's territorial integrity as well as its internal hierarchy.

Figure 6 Lienzo de Zacatepec

These associations had immediate, worldly implications, for the church assumed the temporal roles of the teocalli in everyday governance and the reordering of space. In pre-Hispanic urbanism, the teocalli had formed part of a ceremonial center of stone structures that included a tianquiztli (market) and tecpan (ruler's house or seat of government). Religion, worldly power, and commerce converged in the same space, providing a stage on which political and religious relations were confirmed.Footnote 52 On religious holidays, commoners and subject towns delivered tribute and attended religious ceremonies. In the decades that followed the conquest, a new urban space adapted these Mesoamerican political, commercial, and religious functions to the European plaza, market, and church. At the center of this nucleus was the doctrina monastery. The complex reaffirmed the preeminence of the sub-unit that hosted it over outlying towns and villages, and their subservience was repeatedly reaffirmed by their obligatory tribute deliveries and attendance at masses performed at the doctrina monastery site. Thus the stone church restored the indigenous urbs—the political-religious center—within a Spanish colonial context. Like the teocalli, the church anchored the local indigenous state, binding together its elite networks, with ties of subservience and cooperation, flows of tributes and labor, and the rituals that reaffirmed elite privilege.Footnote 53 These sociopolitical functions of the new teocalli were more urgently needed than ever in aftermath of the 1540s demographic crisis.

As heir to the teocalli, the doctrina monastery helped indigenous polities regroup populations and shore up community lands. Depopulation made land vulnerable to seizure, and it complicated power structures and missionary logistics. In Tlaxcala, for example, the cabildo ordered the construction of three doctrina monasteries specifically in depopulated areas where lands were at risk of occupation by Spanish ranchers.Footnote 54 Across New Spain, indigenous leaders sought to gather “fleeing” Indians and “reduce” them to their local rule.Footnote 55 In the Sierra Norte of Puebla, refugees from the depopulated tropical lowlands fled upslope to Xuxupango, where they were “congregated” around that town's church.Footnote 56 These indigenous efforts coincided with the Spanish colonial policies of congregación, which sought to relocate outlying populations in peripheral areas to European-style towns arranged along a grid with the stone church at the center. However, unlike the more systematic forced relocations of the congregaciones that would occur across New Spain decades later, these mid sixteenth-century relocation efforts were more piecemeal, locally contingent, and ineffectual when they met with stiff resistance.Footnote 57

Doctrina monasteries served more to concentrate power, not people. This, too, reflected Mesoamerican social organization. Since power was on conspicuous display wherever rulers and nobles resided, local rulers prioritized concentrating the elite, not commoners, in the new urban nuclei that developed around the stone church.Footnote 58 This is clearly visible in the municipal records of Tlaxcala. In 1560, Tlaxcalan nobles openly resisted Spanish orders to resettle rural commoners, precisely because outlying lands needed to be worked, occupied, and defended from usurpers. Instead, the noblemen in the local government decided to recruit exclusively among nobles to resettle in nuclei concentrated around the new churches.Footnote 59 Tribute records tell a similar story. Nobles (pipiltin) concentrated in cabeceras where stone churches and cabildos were located, while commoners remained in more dispersed settlements near their fields.Footnote 60 A similar pattern emerged in Yanhuitlán, Oaxaca, where urban nucleation around the colossal Dominican monastery still reflected a pre-Hispanic pattern of settlement more than a European one.Footnote 61 Even in areas where sub-units relocated wholesale to a new urban nucleus, the constituent cellular calpoltin continued as distinct subunits that retained their semi-autonomy. With ruling nobles ensconced in the new ceremonial center around the doctrina monastery, the cellular organization of the indigenous polity persisted.Footnote 62 Whether rulers responded to the crises by relocating sub-units or by concentrating the nobility, the new stone monastery served in either case as their focal point for consolidating political power.

Even while the church emerged as a new teocalli in indigenous communities, however, native rulers never lost sight of the enormous political prestige these structures carried in Spanish colonial politics. They were keenly aware that a doctrina monastery complex with resident friars had the power to change Spanish officials' perceptions of their jurisdictions. The monastery served as conspicuous proof of an altepetl's political and economic viability as a cabecera —the highest status to which an indigenous polity could aspire. Cabecera status provided ample autonomy to local rulers. No other indigenous polity was ranked above it, meaning that all other settlements within its jurisdictions were classified as subject-towns, or sujetos (in terms of the mission, sujetos tended also to be visitas). This freed the cabecera to control its own internal revenue collection and manage its jurisdiction's collective tribute payments to Spaniards. In political terms, the cabecera coordinated labor drafts for the benefit of native elites and Spaniards alike, and it regulated and exploited natural resources within its jurisdiction. Doctrina status provided the clearest pathway to cabecera status. To obtain doctrina status, local rulers needed mendicant support and a viable plan to build a monastery. This was the case for jurisdictions in encomiendas as well as those under royal jurisdiction.Footnote 63 In this way, doctrina monasteries were integral to indigenous struggles for autonomy, and often predominance over nearby towns, within the Spanish colonial system.

At once a colonial mission and a new teocalli, the doctrina monastery was a bicultural structure that fused the symbols and networks of the Spanish Empire with those of the Mesoamerican local state. For this reason, it was the hotly disputed prize in the indigenous territorial struggles that intensified after the hueycocolixtli. As the contrary centrifugal and centripetal forces continued to tug at indigenous polities, building a church furthered all territorial ambitions in this period: it aided some rulers to reassert their domination over their neighbors, helped others secede from their neighbors, and moved still others to join in confederation.Footnote 64 Let us briefly examine how monasteries furthered each of these three contrary forces in indigenous politics after the hueycocolixtli.

First, for polities that had enjoyed political preeminence over surrounding jurisdictions before and after the Spanish conquest, raising a monastery made a strong argument about the antiquity and inviolability of these territories and their ruling lineages. Such was the case of former imperial capitals like Texcoco and Tzintzuntzan, independent kingdoms like Meztitlán and Tlaxcala, former Aztec garrisons like Tepeaca and Tlapa, religious sites like Molango, and provincial trading centers like Izúcar. Nearly all of the 72 doctrinas established before 1540 had been pre-Hispanic power centers. Yet these large jurisdictions were not the sole polities that built monasteries to maintain power. In smaller jurisdictions that claimed authority over surrounding towns, doctrina monasteries strengthened territorial claims. In Tepechpan, whose tlacuilo opened this chapter, a new stone church proclaimed altepetl sovereignty over its sub-units. In fact the construction campaign provoked a protracted dispute between Tepechpan and an unruly sujeto, Temascalapa. In a clear effort to secede from Tepechpan, Temascalapa had refused to provide its laborers for Tepechpan's church, leaving Tepechpan without haulers of lumber in the wake of the hueycocolixtli. This led to a protracted trial between the two towns. Tepechpan eventually won the dispute, securing a legal injunction from royal officials compelling Temascalapa to provide laborers to help build Tepechpan's church. Thus, Tepechpan not only brought a costly project closer to completion; it also reaffirmed its dominance over Temascalapa and prevented the fragmentation of its jurisdiction.Footnote 65

Similar legal disputes arose from church constructions in Yanhuitlán and Totolapan in those years, as cabecera rulers sought to draw on the labor of outlying towns whose historical ties to them were ambiguous.Footnote 66 Such disputes did not revolve around tangibles—the stone church or boundaries—as much as the social ties of obligation, for all parties saw the deployment of labor for church construction as a primary acknowledgment of political subservience. In this way, for polities that sought to maintain dominance over outlying towns or that saw an opportunity to expand, the doctrina monastery—and especially the political and economic processes of its production—served to bolster their jurisdictional claims.

Although doctrina monasteries could bolster some jurisdictions, most mid-century projects empowered precisely the opposite forces—those of separatism. Most of the 80 polities that began construction of doctrina monasteries in the decade after the hueycocolixtli did so in order to separate from a dominant power. These were mid-sized or small local states that had been subjected to stronger regional altepeme where missionaries had first established themselves in the first two decades after the conquest.Footnote 67 Lacking a large doctrina monastery of their own, these jurisdictions were rather oversized visitas whose subservient status did not reflect their size, their history, or their rulers' ambitions. Rulers of these jurisdictions begrudged their rivals' doctrina status, not to mention the fact that they had to lead their townsfolk to their competitors' monasteries for mass and tribute collection. The rulers of the overlooked altepetl of Cuauhtinchan, for example, bemoaned the fact that their proud altepetl was treated “as if we were a sujeto.”Footnote 68 In these jurisdictions, church construction asserted the altepetl's viability as a future doctrina and cabecera. At the Franciscans' chapter meetings, Motolinía tells us, local rulers waited in the wings hoping to lobby the friars to come settle in their jurisdictions and establish a doctrina in their polities.Footnote 69 As a result, much of the post-hueycocolixtli boom in monastery construction can be attributed to separatist ambition, to a desire to secure control over local resources and populations.

Across dozens of large jurisdictions, much of the sweat and labor expended in raising walls and hauling stone formed part of a region-wide fragmentation of indigenous jurisdictions. In Tepeaca, a former regional power in the Aztec Empire, four altepeme, each with its own proud history and ruling lineage, managed to secede by raising monasteries. Passed over by missionaries in the first decades of Spanish rule, one by one Tecamachalco, Tecali, Quecholac, and Acatzingo secured mendicant support and raised monasteries during and after the hueycocolixtli crisis in the late 1540s.Footnote 70 Meanwhile, Huexotzingo, a large pre-Hispanic lordship and early Franciscan doctrina, saw its former dependencies of Calpan and Acapetlahuacan, and its former enemy Huaquechula, achieve doctrina status between 1545 and 1550.Footnote 71 Since church construction became a primary means of secession, it is therefore no surprise that construction campaigns in upstart jurisdictions triggered litigation. Totolapa, for example, fought hard to prevent new Augustinian doctrinas in Tlayacapan (1554) and Atlatlahuca (1570s) from seceding as fully independent cabeceras.Footnote 72 In the end, two decades of transatlantic legal battles could not thwart the autonomy that a completed monastery so concretely expressed.

Finally, in addition to both concentrating and fragmenting territorial power, doctrina monastery construction could also amalgamate separate polities. Mesoamerica abounded in complex polities where multiple nuclei ruled through a careful balance of power. This was often the case of polities with significant ethnic divisions. In these cases Spaniards could not perceive any clear dominant unit or cabecera. Since these jurisdictions lacked an obvious power center, friars and nobles negotiated accords to build their doctrina monastery at a new neutral site. The rulers of the constituent towns would then collectively manage altepetl affairs from the cabildo, which was next to the new monastery. The most salient example of the neutral ground monastery was the city of Tlaxcala, which was situated at the intersection of the four major altepeme that constituted this province.Footnote 73 Monasteries in Actopan and Ixmiquilpan served a similar function.Footnote 74 Neutral-ground monasteries could also join divided ethnicities into a shared government. A prime example of this is the way in which a Franciscan monastery in Tlalnepantla—a toponym meaning “middle ground” in Nahuatl—reconciled Otomís and Nahuas. Similarly, a Dominican monastery on neutral ground sealed a power-sharing arrangement between opposing Chalca and Tlatelolca groups in Tenango-Tepopula.Footnote 75 In these cases, monastery constructions elevated the status of the overall jurisdiction while maintaining the distinctions of the constituent parts. Yet not all efforts to build a neutral ground succeeded: a Franciscan monastery built between Otlaxpan and Tepexí del Río failed to attract the residents of either town, who persistently refused to relocate. As a doctrina without a settlement, Spanish documents referred to both towns when discussing the church that lay between them.Footnote 76

Whether they helped maintain, divide, or amalgamate indigenous jurisdictions, these structures reasserted thee intangible qualities of the altepetl: its history, identity, and ritual. At the same time, they bolstered claims over the tangible markers of power—control over lands, labor, and jurisdiction. The heft of these structures is a testament to the urgency to set such assertions into stone in a time of instability. These ambitions corresponded seamlessly with those of the friar-missionaries, whose own territorial ambitions and rivalries motivated them to encourage these vast projects.Footnote 77 Royal officials could only look on warily on as indigenous rulers and friars agreed to “build big, build solid, and build fast.”Footnote 78 Driven by crisis and rivalry, for three decades the campaigns proceeded on a grand scale.

Nonetheless, in an examining the ways that local efforts to remake local polities drove these campaigns, an account of motive is only part of the story. Behind the ambitions of native rulers and mendicants, behind the mission church's shape-shifting into a new teocalli, there is also a contested social history of labor and class that remains deeply embedded in the walls of every doctrina monastery.

Haulers and Builders

The monastery construction site set the power relations and cultural hybridization of mid-sixteenth century Mexico into stone and mortar. Draft laborers and itinerant skilled artisans resided in busy makeshift camps shrouded in smoke that smelled of corn and wood-fire. Building sites hummed with activity: haulers of stone and timber sang work shanties as they brought in heavy loads on their backs, stonecutters hammered away, carpenters cut beams, acrid clouds of lime and dust swirled about, ropes and pulleys on scaffolds creaked. High above, masons set finished stones into massive walls and soaring vaults. Throughout the site, mandones—native overseers—barked out their orders. Observing the scene, a friar, himself a newcomer to construction, conversed and shared the general plan with visiting inspectors sent by a nervous viceroy to keep an eye on these costly enterprises. At the average site, this scene—this tangle of languages, techniques, tired bodies, and frustrations—unfolded within ten years of the hueycocolixtli. What mobilized commoners to toil without compensation in these projects?

On the rare occasions that scholars have addressed this question, most treat the doctrina monastery as if it were a force of nature, the result of a relatively seamless fusion between timeless Mesoamerican customs and missionary zeal. The production of these monasteries tends to fall by the wayside, leaving only an assumption that thousands of laborers toiled in each project solely out of unquestioned tradition or loyalty to local rulers. Once the friars tapped into the immemorial Mesoamerican customs of working without compensation, so the thinking goes, these vast edifices sprouted like so many mushrooms across the Mexican altiplano.Footnote 79 However, the heretofore largely unexamined archival records of these building campaigns challenge these facile assumptions. Petitions, court battles, and reports of labor strife all indicate that mobilizing the vast resources and labor forces called upon to raise a doctrina monastery required complex negotiations both within and outside the polity. Diverse workforces needed to be coordinated; good stone had to be located, dug up, cut, and hauled over large distances. If limestone was available nearby, it had to be heated and processed to make mortar and plaster; otherwise, the community needed to pay dearly for it elsewhere. The same applied to lumber, essential in all stages of construction, which had to be cut and hauled from forests that were rapidly diminishing. New building techniques, too, had to be transmitted by Spanish or indigenous tradesmen in a society that had no prior experience building immense cavernous structures with high walls and stone ceilings.Footnote 80

Unskilled labor was most essential, but the negotiations to obtain it were fraught with conflict and resistance. “I can swear to you, as a Christian,” a Franciscan friar once admitted, “that there is not one stone [in these walls] that did not require a thousand Indians pulling it to get it here.”Footnote 81 The high cost of these projects, in terms of man-hours and tribute, stretched political negotiations to the maximum. To mobilize multitudes of macehuales (commoners), indigenous rulers had to carefully negotiate territorial rivalries and strained class divisions within their polities. Yet the potential reward was substantial: in the majority of cases where native states successfully coordinated mobilizations of labor and resources, the completed project proved the local state's viability. Each stone delivered and each beam raised by commoners under the command of local rulers reaffirmed ties of subordination and deference. To contribute to the raising of a teocalli, be it for Ahuitzotl or for the town of Tepechpan—as Luís Quiab, a 55-year-old native witness of preconquest Mexico, declared in 1550—also raised a Mesoamerican political structure.Footnote 82 Thus the very means of producing a monastery was a political end in itself, whose meaning was known to ruler and laborer alike.

Since communities often had to look beyond their jurisdictions for quarries, lime pits, and forests, the roads of mid sixteenth-century Mexico were crowded with teams of macehuales hauling immense stones, tree trunks, and baskets of lime over long distances.Footnote 83 The indigenous rulers of Acolmán, for example, deployed their commoners in 1576 to the woodlands above Texcoco to cut lumber for an enormous retablo (altarpiece) in their newly finished church: this required eight beams and 100 planks for the scaffolds, and 155-foot beams for the retablo itself. The commoners hauled this lumber on their backs over a distance of at least 40 kilometers.Footnote 84 The indigenous system that mobilized these multitudes was known as the coatequitl. With antecedents extending long before the Spanish conquest, the coatequitl was a labor draft shouldered by commoners. Local rulers mobilized this draft for public works projects like temple construction, for their own benefit, and for imperial authorities—first for Aztecs and later for Spaniards, including friars. The coatequitl served as the linchpin of indigenous politics, for it reaffirmed the internal hierarchies of class and territoriality within the polity. Indeed, it determined one's class: participation in the coatequitl was what defined the commoner while the distinguishing marker of nobility (pipiltin) was one's exemption from it.Footnote 85 Each mobilization of the coatequitl therefore renewed the hierarchies of class in indigenous polities.

In a similar fashion, the coatequitl also reaffirmed the cellular and rotational organization of the local indigenous state. Each sub-unit was responsible for providing a constant stream of macehuales to perform specialized tasks in communal projects.Footnote 86 A rare record from Tlatelolco provides a vivid example of the coatequitl in action. Describing the labor arrangements for building a tecpan (ruler's palace), the 19 sub-units of Tlatelolco stipulate their respective tasks: Tequipehuqui and Nepantla are to build a great hall “with sixteen or seventeen colonnades and 56 varas length”; Cuauhtlalpan and Tecalca were to install pipes for potable water; Cuauhtepec and Tepetlalca would “provide food for everyone else.”Footnote 87 The division of labor thus required careful coordination based on each sub-unit's natural resources and workforce specializations. Cuernavaca's heavily forested sujeto of Quaxomulco, for example, declared in a primordial title that its coatequitl obligations consisted of providing lumber from its ample forests and carpenters for the doctrina monastery in their cabecera.Footnote 88 Tribute rolls in Tlaxcala and Huexotzingo tell a similar story, carefully noting the numbers of stonecutters, masons, lumberjacks, carpenters, and painters in each sub-unit.Footnote 89

This rotating cellular system allowed for thousands of laborers at a time to mobilize in large-scale projects that required significant coordination and specialized tasks. Coatequitl laborers were organized into groups of 20. To build a monastery in Tula, for example, indigenous rulers, friars, and viceregal officials concurred that each of the polity's three sujetos would continuously provide 20 commoners per day until construction was completed. A similar agreement for building the Dominican monastery in Nexapa detailed exact coatequitl requirements: 18 sujetos would provide from three to 20 workmen each. Each sub-unit was to provide consistently the number of workmen stipulated in the order: “Xaltepeque can give eight Indians,” the document reads, while “Tonacayotepeque is to provide 12 Indians,” Petlacaltepeque six Indians, Tlalpaltepeque 20 Indians, and so on.Footnote 90

For commoners, coatequitl draft labor for large monastery construction projects was a long-term burden that joined many other tribute and labor commitments. The colossal Dominican monastery at Yanhuitlán in Oaxaca, shown in Figure 2, consumed the unpaid labor of 6,000 commoners who toiled in ten rotational shifts. In other words, on any given day 600 men were working at the construction site. According to laborers working at the site, every tribute-payer was spending ten weeks every year providing their unpaid labor to raising this behemoth—“four weeks for building the church, two to remove stone from the quarry, two to make lime, and one in the forests to cut lumber, and another to haul lime back to the monastery.” This, in addition to 16 weeks spent working on friars' and caciques' lands, as well as tribute payments, was leaving the commoners “without any time to work their own plots.” Given that this construction campaign dragged on for 25 years, all while their population declined, the commoners must have felt as if their labors would never end.Footnote 91 The plight of Yanhuitlán's macehuales raises a vital question regarding the social production of doctrina monasteries. Given that coatequitl labor forces juggled multiple tribute and labor burdens that only increased as their numbers diminished, on what terms did they participate in these campaigns? What motivated sub-units and commoners to toil in these projects?

Perhaps due to the scarcity of sources, it has become something of a commonplace to assume that commoners willingly accepted these burdens out of deference to immemorial tradition. Christian Duverger, for example, has argued that indigenous populations “spontaneously provided part of the collective labor that was laid out in their ancient laws.”Footnote 92 Since pre-Hispanic times, so the argument goes, indigenous commoners had been providing their labor for temple construction voluntarily and enthusiastically, out of a unanimous sense of community pride and tradition that they shared with their rulers. In this vein, too, James Lockhart has argued that monastery construction was driven by a sense of altepetl pride that transcended class divisions.Footnote 93 Others, meanwhile, have argued that coatequitl was in fact not labor at all, but instead was the result of a “compulsion for ritualized labor” that formed part of an unaltered Mesoamerican tradition. In effect, indigenous commoners labored solely out of a need to maintain Mesoamerican ritual cycles in their daily lives.Footnote 94 Tellingly, these arguments draw heavily on mendicant authors who claim that indigenous laborers offered their labor with delight—an uncritical, even literal, reading of the friars' defensive polemics.Footnote 95 Whether the motivation was altepetl pride or the power of ritual, the underlying assumption here is the same: that commoners toiled away simply because this was the order of things.

A closer look at the sociopolitical context of the coatequitl, however, reveals a labor system that was rooted not in tradition, but in the give-and-take of everyday politics. In the sujeto of San Juan Teotihuacán, for example, commoners protested plans to turn their visita into an Augustinian doctrina, in spite of the higher political status that this would have given to this proud and ancient jurisdiction, because the plans entailed a long building campaign for a religious order known for its architectural largesse. Indeed, commoners needed only to look next door to Acolmán, where construction on a massive Augustinian complex had dragged on for decades.Footnote 96

Like the teotihuacanos, communities throughout central Mexico weighed the costs and benefits of monastery construction. Their petitions, protests, and internal records attest that labor drafts for monastery construction functioned as a social contract in terms of both the class structure and territorial makeup of the polity: the drafts reciprocally bound commoners to local rulers, and sujetos to cabeceras. Coatequitl labor was unpaid, but it was by no means free. At the heart of the coatequitl there was a material transaction directly linked to the individual commoner's right to farm plots of land for subsistence. Coatequitl labor gave commoners—who were generally landless—the right to cultivate a plot in usufruct from the calpulli sub-unit.Footnote 97 In Cuauhtinchan, for example, an indigenous land record lays out a noble's perspective of the sociopolitical order: “Only tlatoanis [rulers] hold lands, in their lands they rule, in their lands they favor the commoners”—that is, the ruling nobles in altepeme and calpoltin provided commoners with access to lands in exchange for their participation in the coatequitl. In addition, there are indications that the coatequitl also included an expectation that workers would be fed in exchange for their labors. “At most,” the Franciscan Fray Jerónimo de Alcalá wrote, “they would be fed in the monasteries where they worked and built.”Footnote 98 Indigenous communities frequently made their protests known when Spanish and indigenous rulers violated local agreements exchanging land for tributes and labor.Footnote 99 More than a timeless ritual, then, the coatequitl was based on a reciprocal, if unequal, exchange of labor for land access. Despite the asymmetry in power relations between commoners and nobles (and, for that matter, between commoners and Spaniards in general), these understandings were not lost upon those who had to perform this grueling labor.

A similar transaction characterized the coatequitl in territorial politics. For sujetos, participation in church construction campaigns reaffirmed local boundaries and hierarchies of power. In exchange for benefiting from their labor, altepetl and Spanish authorities recognized local rulers of the sujetos and confirmed their boundaries. This reciprocity is particularly evident in the “primordial titles,” the historical narratives that indigenous elders put to paper to defend local land claims in the seventeenth century. A number of sujetos in Cuernavaca, for instance, declared that they had contributed their commoners' labor and building materials for the construction of the Franciscan monastery in their cabecera in exchange for confirmation of their lands and ruling lineages by altepetl rulers and Spanish authorities. “Because we helped make the [cabecera] church of Cuernavaca,” the authors of one primordial title in San Juan Chiamilpa wrote, “we received our land grant . . . and our boundaries were measured.”Footnote 100 In effect, “by trumpeting their willing and voluntary support of the cabecera's church,” Robert Haskett writes, “[the sujetos] are asserting their own autonomy.”Footnote 101 Thus, just as coatequitl labor reaffirmed an individual commoner's right to land, so the labor of his tequitl—his sujeto work squad—also reaffirmed his sujeto's collective rights to lands and resources.

Yet while the coatequitl was an expression of commoner and sujeto rights, it was also a social contract that dangled on the thinnest of threads. Dependent as it was on demographic stability and competing with other tribute and labor burdens, the political and economic model of the coatequitl was set on a downward spiral over the course of the sixteenth century. The overall decline and periodic crashes of population only increased the per capita burden every time the inflexible demands of church construction rotated back to sub-units and barrios. With fewer and fewer hands available, the burden of coatequitl began to infringe on the time that commoners needed to sustain themselves on their own plots. In these circumstances, indigenous commoners and sujetos did not resign themselves to the increasing workload out of an unquestioning devotion to their altepetl or to their ‘rituals.’ Instead, many towns resisted coatequitl drafts in ever-greater numbers after the 1550s.Footnote 102 In Jantetelco, for instance, 400 laborers in the cabecera and sujetos were slated for labor drafts to build a Dominican monastery in the 1570s; when this already meager number was severely cut by epidemics two decades later, the sujetos simply withdrew their surviving laborers from the unfinished church.Footnote 103 Meanwhile the commoners at Yanhuitlán, whose herculean labors we saw above, were so hard pressed that they demanded a reprieve in order to feed themselves. In their depositions, they directly faulted the friars and local rulers for their opulent architecture, which had a detrimental effect on the commoners' household economies.Footnote 104 In other cases, commoners simply withdrew their labor. Construction campaigns collapsed amid macehual protests in Tlapa, Calimaya, and Pahuatlán, where four forlorn Augustinians reported in 1579 that commoners had left their cells thinly covered with thatch, and the adobe church was disintegrating before their eyes.Footnote 105 In the end, feeding one's family was a far more important ritual than building a monastery.

Dissident sujetos also resisted coatequitl drafts for monasteries. Sujeto labor for cabecera church construction and repair was a pillar of cabecera political authority. As in pre-Hispanic society, labor drafts for the construction and maintenance of temples defined the relations between dominant and subject states. Sujetos petitioned viceregal authorities for assistance when they believed that cabecera-altepetl rulers were unduly exploiting the coatequitl to their detriment, while others chose to provoke a crisis by refusing to send their laborers.Footnote 106 In 1565, for example, commoners in Tlayacapan openly revolted against native officials from Totolapan who were attempting to reduce their town to sujeto status in light of the fact that they had been compelled to help build Totolapan's monastery. Stone-throwing macehuales forced the officials to seek refuge in Tlayacapan's monastery, passing a nervous night while the crowd outside in the atrio pelted the walls. The commoners of Tlayacapan had never desired to haul stone and lumber for their rivals in Totolapan, and now they violently resisted efforts to transform their grudging labor into long-term subjugation.Footnote 107

When faced with such resistance, native rulers in cabeceras had no choice but to petition the viceroy for assistance in compelling dissident commoners and sujetos—or “rebellious Indians,” as frustrated rulers in Tepetotutla called them—to compel them to return to work.Footnote 108 As reports of these conflicts reached the viceregal chancellery, the resulting investigations tended to side with the local rulers and the friars over the commoners. A well-documented case in Tepeapulco in 1575 provides a dramatic example. There, the sujetos and the cabecera collided over the cabecera's right to use sujeto labor to build a second doctrina monastery in their jurisdiction, in the town of Apam. Apam, however, was only a sujeto, not the cabecera. In a series of petitions sent to Viceroy Martín Enríquez, five sujetos of Tepeapulco argued that their cabecera rulers had violated a basic principle of coatequitl labor: sujetos had to provide draft labor for the cabecera, they argued, but not for other sujetos.Footnote 109 After all, it was the cabecera of Tepeapulco that guaranteed access to local lands in exchange for coatequitl labor, not Apam. Moreover, this was especially grievous, since they already had many other obligations to Spaniards and native rulers: the sujetos under Tepeapulco provided coatequitl labor for Spaniards in Mexico City (some 70 kilometers away), they were sending laborers to the still-unfinished Franciscan monastery at their doctrina in Tepeapulco, they were trying to build their own visita churches, and they had to “supply the mesón” (inn) in the cabecera with provisions. All this, they declared, left them with little time to feed themselves, let alone trek 20 kilometers to build yet another monastery in Apam. “We have few people and cannot give any more [labor] for anything else,” declared the Indians of Tlatecaguan, conveying a sense of exasperation that still seems to leap off the document some four centuries later.Footnote 110

Expressing concern, the viceroy ordered an investigation by the local corregidor. Most importantly, the viceroy wanted to know why one sujeto was being privileged over the others.Footnote 111 In this, history might have provided some guidance: prior to the Spanish conquest, Apam had played a prominent role as the site of an important fortress that guarded the Triple Alliance's hostile mountain frontier with its archenemy, Tlaxcala.Footnote 112 Demography also likely played a factor, since Apam had twice as many people as the nearest contender among Tepeapulco's sujetos. When a third major cocolixtli epidemic decimated the population of Tepeapulco in 1575, Apam emerged relatively unscathed and soon rose to prominence in the area. By the mid seventeenth-century, in fact, Tepeapulco would be demoted to visita status to Apam, which became the doctrina in this jurisdiction.Footnote 113 For Viceroy Enríquez, there were two options. He could back the sujetos' argument that coatequitl labor was intended solely for the cabecera, or he could accept the will of the indigenous rulers of Tepeapulco and Apam. Echoing the corregidor's report, the viceroy decreed that the sujetos of Tepeapulco should “assist the said church of Apam by their turns.” The viceroy not only declined the sujetos' petition to spare them this extra labor; he also negated their arguments and reinforced the authority of local rulers. Nevertheless, he softened the blow by appealing to the reciprocal understandings that undergirded the coatequitl: the residents of Apam, he stated, would be obligated to respond in kind for the assistance that they were receiving from these poorer sujetos. In this way, the viceroy attempted to reestablish reciprocity in a tense situation where the aggrieved sujetos only saw exploitation.Footnote 114

Throughout New Spain, monastery construction proceeded for a time despite population losses, based on a basic political bargain inside each indigenous polity. In hundreds of major construction projects, sub-units and commoners contributed their labor to the temple-monastery in their altepetl as a way to strengthen a broader indigenous polity that, in turn, would protect and legitimize their jurisdictions and rights to access land. The proliferation of doctrina monasteries is evidence of the functioning of these reciprocal understandings in hundreds of jurisdictions. But as seen in the resistance that broke out in Tepeapulco, Tepechpan, Tlayacapan, Tlapa, and other jurisdictions, when a church construction project appeared to violate this social contract, the monastery project was itself in danger. While commoners mobilized labor for projects in their political sphere according to reciprocal understandings, without reciprocity all else was but labor, to be best remunerated with a wage.

Conclusion

In the words of the elders of Sultepeque, in the seventeenth century “We built it, not the Spaniards.”Footnote 115 In the second decade of the seventeenth century, the Augustinian chronicler Fray Juan de Grijalva looked back 60 years to what already seemed to be a heroic age. Even in the aftermath of the great cocolixtli of 1545, he wrote, enough indigenous hands had remained “to show the greatness and generosity of their souls.” Through their labor, the kingdom of New Spain abounded in “proud edifices, so strong, so great, so beautiful and so architecturally perfect that [they] have left us with nothing more to desire.” By his time, the wealth of New Spain rested on its minerals, but Grijalva waxed nostalgic for the depleted riches of the missionary. To him, the great sixteenth-century monasteries were “witnesses for posterity to the opulence of the kingdom and to the great number of Indians that there once was.” What the indigenous population in New Spain had accomplished in the 1550s and 1560s, he implied, could not be repeated; the seventeenth-century indigenous and mendicant inheritors of these buildings were left to admire what this earlier generation had accomplished and defend what remained.Footnote 116

As the result of a colossal human enterprise, the doctrina monasteries of Mexico are the most tangible record of indigenous responses to the series of tragedies that they experienced in the sixteenth century. The production of hundreds of churches in the shadow of death, in that space of time so starkly portrayed on the Tira de Tepechpan, was fraught with conflict and struggle, but once the structure was built and completed it stood as visible evidence of local political sovereignty—evidence as important for indigenous communities as it was for Spaniards who saw it as tangible proof that Christianity had indeed laid roots in Mexico. So powerful was it that dissident sujetos and commoners knew that the most effective resistance was to erect a church of their own. Territorial disputes, age-old rivalries, and class struggles between nobles and commoners are embedded in these walls. These immense structures embody the efforts to rebuild in a disastrously transformative time—efforts that often proved more fragile than the stone and mortar of their hulking walls.

Over time, however, complex memories of conflicts over church construction faded, and the monastery fully assumed its role as a symbol of unity and consensus. While Grijalva wistfully looked back at this heroic time, the indigenous communities that inherited these structures embraced them as proof of their own legitimacy and vitality. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as elders retold their community histories, church construction served as a foundational story and as a justification of local ruling lineages in written narratives that have come to be known as “Primordial Titles.”Footnote 117 In one poignant record, a nobleman reminds future generations that the destiny of their community would be forever intertwined with that of the church that he had raised: “I, don Pedro de Santiago Maxixcatzin, vecino of Quatepec, state that the Franciscan fathers baptized me and my brother don Juan Mecatlal, and they were the ones who founded the church of San Miguel; and we built it, not the Spaniards. And so, my children, I entrust you to care for all of the belongings of the church: the surplice, banner, chalice, [and] bell; all are belongings of Quatepec of San Miguel.”Footnote 118 For them, as for the tlacuilo of Tepechpan, the sixteenth-century church embodied their community, powerfully asserting its vitality and endurance.