Aim of the project

Large-scale raw material exchange systems connect production from source to demand in a distant location, regardless of whether this demand is for the supply of abundant goods, such as small tools, or for a few highly valued diplomatic gifts. What happens between the source and the find spots is a matter of interpretation: a wide variety of motivations, forms of exchange and differently interlocked regional economic networks of limited reach are to be assumed, whose interactions result in highly complex systems (Brughmans Reference Brughmans, Brughmans and Wilson2022).

This project explicitly does not reconstruct complete economic or social networks, but rather seeks and measures key parameters, some of which are also known from the field of social network analysis. Those parameters can then be followed through time and space where they indicate changes and represent economic and social trajectories. Here, we introduce the project via a case study and invite broad collaboration on providing a platform for joint work.

In the project, however, the analysis is based simply on sources and the find spots related to them. For strictly analytical purposes, this connection is assumed. The aim is not to map entire exchange systems nor to follow individual production stages or exchange steps—the thin, often heterogeneous data structure makes this impossible in most cases.

Within network science, those relations that connect source to find spot by a directed relationship are conceptualised as bimodal (Wasserman & Faust Reference Wasserman and Faust2019). In combining these spatial and chronological distributions of different raw materials’ interdependencies, interchangeability and economic side effects become visible. Within the project, some of the most important examples of outstanding, large-scale exchange networks in prehistory are assembled (Figures 1 & 2). Data collection is currently being expanded to Africa and Asia. The project focuses on how the simultaneous distributions of different commodities were related to the actors’ more or less limited access to resources; in doing so, fundamental questions of social inequality and power relations are addressed.

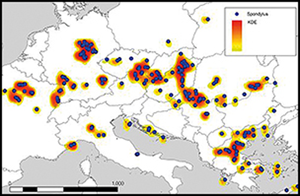

Figure 1. Sites with selected sourced raw materials (>6000 sites) (map by S. Strohm).

Figure 2. Raw material distributions in the continuously updated “Big Exchange” database in chronological order (for corresponding references, see the online supplementary material (OSM)) (figure by J. Hilpert).

A first example: Central Europe's first farmers’ exchange

We present new results for one of the best researched Central European areas and most studied find groups: the north-western Linearbandkeramik Culture (LBK; for extensive references, see Armkreutz Reference Amkreutz, Gronenborn and Petrasch2010; Otten et al. Reference Otten, Kunow, Rind and Trier2016). Combining the raw materials in circulation between 5500 BC and 4900 BC provides important insights into the potential of our approach. The first Central European farmers of LBK settled predominantly on isolated patches of loess-derived soils. The spatial expansion of the Neolithic lifeway followed a leapfrog model from patch to patch (e.g. Fernandez-Dominguez & Reynolds Reference Fernandez-Dominguez, Reynolds and Puchol2017), often keeping the flow of raw material constant in the direction of the line of assumed descent—the social lineage (Kerig Reference Kerig2008).

In contrast to research into the Metal Ages, studies of the Stone Age have often centred on flint, in most cases not a luxury item. However, flint, in the broadest sense, along with ground stone raw materials, might have played an important role in signifying or even channelling social relationships (for locations and references, see: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/neomine; Figure 1).

The combination of datasets with different raw materials enables the reconstruction of more complex relations, such as economic choices, where certain raw materials are substituted for others (cf. Knappet Reference Knappet, Light and Moody2021). Here, the data science part of the project comes in: the data integration process focuses on potential for automation as well as domain and research data management requirements. The integrated relational data are mapped to a Heterogeneous Information Network (HIN) to enable the exploration of relationship patterns with a variety of graphical and data mining techniques (Shi Reference Shi2017).

Regional LBK groups can be distinguished by ceramics. The north-western LBK (NW group) is characterised by a good supply of flint of Rijckholt origin (Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann1995), but the absence of materials that are otherwise widespread in Central Europe is now becoming apparent; the lack of Spondylus, for example (method: Figure 3), in the north-west was suspected to result from local poor preservation conditions (cf. Eckmeier et al. Reference Eckmeier, Altemeier, Gerlach, Cziesla and Ibeling2014). The region from which these shells are missing, however, is considerably larger than the area with poor preservation. Recent excavations of cemeteries in the NW group (Peters Reference Peters2018) additionally suggest that this absence reflects the past Spondylus distribution (Windler Reference Windler2018). Thus, analysis of multiple raw material distribution within a network perspective reveals that the NW group is framed by exchange sub-systems in which the NW group played little or no part (Figure 4). These sub-systems reflect the expansion of the LBK, assuming that exchange mostly followed established contacts in accordance with the social lineage of the initial spread.

Figure 3. Schematic overview of workflow (figure by J. Hilpert).

Figure 4. Case study: Early Neolithic Central Europe (LBK) (figure by J. Hilpert).

We reconstruct a pattern called ‘directed percolation’, similar to a braided stream (Hinrichsen Reference Hinrichsen2000), whereby the exchange probability between individuals decreases with spatial distance and increasing bifurcations. Such an expansion allows easy reconnection in the direction of the origin, following the least social distance but hinders exchange with neighbouring groups (Figure 5). The NW group—for a long time a model region of LBK research (Hilpert Reference Hilpert2017)—is such a case within the LBK: a ‘clique’, in network terms.

Figure 5. a) Broad trajectory of LBK expansion; b) interpretative model of the LBK expansion into the north-western province. Arrows represent main directions of movement; small arrows indicate the later exchange of raw materials (AHS, Atlantic shells, Spondylus, flints) along lineages of descent (figure by T. Pape).

Perspectives: an invitation

Researchers working on sourced finds are invited to join the ‘Big Exchange’ initiative: an international network of researchers from archaeology, material and data sciences, which guarantees professional and sustainable data management, assuring the authors full control over their data at all times.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the contributors of data.

Funding statement

The project receives funding by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under Germany's Excellence Strategy – EXC 2150–390870439.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2023.78.