The history of paper money in France is usually associated with the figure of John Law who, with the support of the regent, Philippe, duc d'Orléans, between 1716 and 1720, carried out financial experiments to sustain the French currency on the international money market, boost economic activity and restructure the war debt accumulated in the course of Louis XIV's wars. However, as John Law acknowledged, France had already used paper money, and the dire memory of this earlier monetary experience featured high among the arguments of those, in government, who initially opposed the Scot's proposal to establish a bank and issue notes. ‘The public’, John Law observed in December 1715, ‘is against the bank because of the billets de monnoye [mint bills], of the caisse des emprunts, etc., which have brought great prejudice to commerce and individuals’ (Harsin Reference Harsin1934, ii, p. 274).

That first introduction of fiat money in the kingdom took place on the initiative of Michel Chamillart (1652–1721), who held the posts of both contrôleur général des finances (1699–1708) and secrétaire d’État de la guerre (1701–9). The decision to issue paper money as legal tender is certainly Chamillart's most original and dramatic (if largely forgotten) contribution to the history of France, as it led to the first experience of fiat money inflation. Not surprisingly, this experiment has not gone unnoticed by fiscal historians (Boislisle Reference Boislisle1899; Seligman Reference Seligman1925; Harsin Reference Harsin1933; Lüthy Reference LÜthy1959; Dessert Reference Dessert1984; Thiveaud Reference Thiveaud1995). Yet, due to the complexity of money matters, and the language hurdle, this body of literature remains largely inaccessible to non-French specialists. Moreover, in a recent important Anglophone study of Louis XIV's finance, Rowlands (Reference Rowlands2012) pointed out that this scholarship engaged with only some aspects of the paper money experience. To an extent, this is also true of the latter's more comprehensive work and Bonney's earlier contribution (Reference Bonney2001): for the question of the origins, development and impact of paper money is part and parcel of the broader problem of war finance in Europe in the last 25 years of Louis XIV's reign.

The period under investigation here was dominated by two major conflicts, the Nine Years’ War (1688–97) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), in which most Western European states united against Bourbon power. Funding these two long international conflicts put formidable pressures on the resources of all the belligerents. The supply of troops deployed in foreign territories and support to allies generated monetary problems which have been impressively discussed by Jones (Reference Jones1988) and Graham (Reference Graham2015) in the case of England, Brandon (Reference Brandon2015) for the Netherlands and by Rowlands (Reference Rowlands2012, Reference Rowlands2014) for France. Despite Rowlands’ superb effort to identify the shortcomings of French monetary policy, in particular its impact on the external value of the French currency and the capacity to sustain the war effort, yet more work on money and credit in the age of Louis XIV is needed to catch up with the substantial and expanding body of literature on the English fiscal and monetary experience in the age of the Financial Revolution.

Indeed, no single study can encompass the unusually large body of primary sources available to the historian, including serial data on the evolution of the French money stock, about the financing of war under the Sun King. In this respect, Boislisle's massive edition of the correspondence of Louis XIV's finance ministers can be misleading as it covers a small portion of the existing material: recently, Stoll (Reference Stoll2008) went so far as to suggest that it might be best to burn this work. While Boislisle (Reference Boislisle1874–97) did a rather good job in selecting some of the key documents, he could not publish the many letters and memoranda sent by leading experts to Chamillart, or to his advisors, let alone his autograph annotations. Yet the reading of these documents, of which some are undated and dispersed, is essential to appreciate both the role of individuals and institutional constraints in the formation of fiscal policy. In this respect, I believe that Rowlands’ excellent work on Louis XIV's finances is wrong in its assessment of Chamillart's abilities and alleged blindness to the evil advice of corrupt advisors and dishonest bankers. If it seems unlikely that Chamillart will ever be seen as a great minister by historians, his published and manuscript notes show that he was deeply aware of the shortcomings of Louis XIV's fiscal system and, for this very reason, sought to exercise firmer control over the financial community (Félix Reference FÉlix2015) and introduce fiscal reforms. Yet, as I will argue, his aims and achievements were severely hampered by domestic politics and the external pressures of international warfare.

All the warring countries of the period were confronted by the challenge of funding the outcome of decades of military change which had finally brought about a Military Revolution in warfare on land and sea (Black Reference Black and Rogers1995). None of the polities involved had a roadmap to address this challenge: solutions had to be devised piecemeal and revisited as the fortunes of war altered the parameters of fiscal policy. In England, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the ensuing Financial Revolution were the most visible responses to the challenges posed by Louis XIV's ambition, and several scholars (Dickson Reference Dickson1967; Wennerlind Reference Wennerlind2011; Desan Reference Desan2014) have shown how these led to a new monetary constitution which successfully addressed what Bernholtz (Reference Bernholz2003) has called the ‘inflationary bias of monetary regime’ to fund wartime deficit. Yet not all problems were solved: for example, Kleer (Reference Kleer2015) has identified limits to the capacity of the Treasury and the Bank of England to circulate credit instruments in the form of exchequer bills.

On the face of things, meanwhile, the French political system – the so-called absolute monarchy – went essentially unreformed. But new men came to power and the context, both at home and abroad, did change (Collins Reference Collins2009). Notwithstanding the introduction of new taxes (McCollim Reference Mccollim2012), the earlier quote from John Law reminds us that various credit and monetary experiences took place simultaneously and consecutively during the War of the Spanish Succession. For Louis XIV's ministers were well aware of the need to adjust France's monetary regime to international challenges. As the famous banker Jean-Henri Huguetan told Marlborough, Louis XIV accepted the will of Charles II of Spain in favour of his grandson, leading to the War of the Spanish Succession, partly because he was confident that the French stock of money was large enough to sustain a new conflict.Footnote 1 On the central problem of credit and the nature of money, Versailles was observing new developments abroad through contacts with financiers and international bankers, in particular over the question of what would later be called chartalism, i.e. the power of the ruler to issue money and sustain public confidence in its value.Footnote 2 Not surprisingly, Louis XIV favoured royal intervention in preference to the market and tampered with French currency: between 1689 and 1726, France experienced a period of monetary instability, with 79 changes in the nominal value of the livre tournois (lt.), the French money of account (see Figure 1).

It is against this background of devaluations and revaluations, of French institutional tradition and alternative models in the Netherlands and England, and the need to fund warfare, that Chamillart's contribution to fiscal policy and its impact must be assessed. Accordingly, this article will first analyse the decision in 1689 to alter the nominal value of the coinage and describe how a new technique, called réformation monétaire, facilitated the first in a series of five debasements between 1689 and 1709. It will then show how difficulties facing France when Chamillart took the finance portfolio in 1699 initiated new thinking about the fiscal system, and examine how the need to fund the new war led to the re-establishment of Jean-Baptiste Colbert's Caisse des emprunts (CdE) as well as a third debasement, associated this time with the circulation of mint bills (1701). The article will then engage with the fourth debasement (1704), looking at the causes for its failure and examining how the ensuing credit crunch was successfully addressed by a new issue of mint bills which became fiat money. In the final section, the article will focus on the depreciation of bills against specie from 1706, paying attention to the impact of military defeats and the ways in which Chamillart's and his successor Desmaretz's successive policies were designed to tackle inflation while relying on the resource of monetary instruments to finance war deficit. The conclusion will revisit the question of Chamillart's reputation and effectiveness by examining the institutional dimension of fiscal policy and decision-making in the absolute monarchy.

I

There was a relatively complex rationale behind the French government's decision in 1689 to alter the value of the livre tournois. The private papers of Claude Le Peletier, who succeeded Colbert in 1683 as contrôleur général des finances, contain 18 memoranda expressing various concerns about the monetary situation.Footnote 3 These documents show that from the mid 1680s a number of financial advisors challenged the long-established principle that the monarch should never alter currency. The main reason for this change of approach was the alleged scarcity of money, which these advisors attributed to an aggressive international environment where merchants and polities competed for bullion. Louis XIV's attempts to eradicate Protestantism in France also contributed to the economic malaise and the general feeling that the monetary stock was severely depleted. In the aftermath of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), prominent Huguenot actors in the economic and financial sectors chose to emigrate and transferred their assets abroad.

In practice, knowledge about the actual French stock of money was lacking. After some discussions in the King's Council, Le Peletier came to the conclusion that the kingdom, on the basis of annual peacetime royal revenue of 110 million lt., had probably no more than 200 million worth of coins, and even less according to pessimists. The financiers disagreed: Louville, for instance, argued that the country was still very rich, that Colbert had estimated the money stock to be over 500 million and that it was still at least 400 million (Lecestre Reference Lecestre1895, pp. 132–3). And he was right: as we will see, the first debasement (1689–93) brought to the mints no less than 465 million worth of coins. According to a recent estimate, the French monetary stock may have been in excess of 600 million lt., or c. £36 million (Jambu Reference Jambu2015, p. 61). As a point of comparison, in 1696 the English recoinage worked £6.5 million worth of clipped silver coins out of a stock estimated at over £9 million, or c. 150 million lt. (Li Reference Li1940, pp. 256–7).

The absence of accurate and credible information about the coinage was a major stumbling block for planning economic and fiscal policy, let alone a war. As international tensions grew in the late 1680s, concerns about the stock of money became a burning priority: if Le Peletier's evaluation was correct, it was difficult to see how France could sustain a major war against Europe without having to offer a high premium on its loans and draining the country of its metal reserves to pay the royal troops stationed abroad. When the Nine Years’ War broke out the government was forced to address the issue. Three royal decisions were announced in December 1689. A declaration restricted the amount of silver tableware that individuals, including the king himself,Footnote 4 simultaneously, could keep at home. A royal edict ordered the excess silverware to be brought to local mints where the metal would be melted and handed back in newly minted coins. The king completed the new legislation by ordering all coins produced since the 1640s to be sent to the mints where they would be déformées (altered) and réformées (refashioned). This decision initiated the first in a series of four major restampings of the French coinage which, under Chamillart, would make the introduction of paper money both a possibility and, under special circumstances, a necessity.

The advantages of a restamping of the coinage (réformation monétaire) are probably best explained by describing what happened to the coins at the mints. First, the gold and silver coins were checked (to get rid of false ones), counted, and their face value in livres tournois, which was fixed by royal decree, calculated. Since the production of coins took time and the government was unable to immediately exchange new coins for old ones, a receipt was normally delivered to the owners of the coins. Then the coins to be restamped were passed over to workers who used a new technique, invented by a sieur Castaing, whereby the stamp on both sides of the coin would be suppressed and the clean flan made ready to receive a new stamp. The new technology, however, was not available to all the mints: most of the coins were simply struck again, i.e. they received a new stamp on top of the existing ones, which sometimes obscured the details, especially after successive restampings of the coinage, and facilitated fraud. Use of the old coins was prohibited henceforth, but they were still accepted at the mints – at a lower price – thus creating the ideal condition for Gresham's law to operate. In short, the restamping – or overstamping – altered the surface appearance of the coins but, crucially, it did not affect their intrinsic properties, in particular their content in precious metal.

The restamping of the coinage was essentially a new method of debasement of the currency. In contrast to the traditional debasements by reminting or recoinage, a restamping presented various advantages. It could be done without melting the old coins, a costly operation, and assaying the new ones, usually a protracted business. A restamping was also a tax in kind (seigniorage) levied on the monetary stock. For it was always linked to an augmentation des monnaies, i.e. an increase in the nominal value of the coins. In other words, the owner of coins would receive back from the mint the same value in livres tournois but in a smaller number of coins of nominally higher value. The benefits of the operation were, moreover, immediately forthcoming. In 1689, for instance, the king kept one out of every 30 silver écus (and one out of 18.3 gold louis) restamped. At the beginning of a war, a restamping was considered an ideal method of raising cash swiftly, thus allowing the state to deploy impressive military forces to deter enemies. A restamping facilitated intervention on the domestic money market: it was usually associated with incentives for hoarders to invest their savings in new royal loans or offices marketed by the king's financiers, with the capital stipulated in livres tournois (money of account) payable in new coins of the same metallic worth but higher nominal value. Pressure on the public to empty their coffers was maintained by announcements of future diminutions, i.e. reductions in the purchasing power of coins, which, for the investors, would result in a plus-value on capital. Eventually, when the coins were restored to their initial value, the whole operation could be started over again.

In total, five debasements took place under Louis XIV, four by the method of restamping (1689, 1693, 1701 and 1704) and one by reminting (1709). Of course, these operations had side effects. The stock of coins and the velocity of money were affected because many tried to evade the king's tax. Debasements impacted directly on the domestic economy via the foreign exchange, which added to the disturbances caused by war. The co-existence of gold and silver coins of different nominal values but with identical metallic content offered opportunities for fraud (Lüthy Reference LÜthy1959; Lévy Reference Levy1969; Rowlands Reference Rowlands2014). The pros and cons of French monetary policy generated intense debates throughout Louis XIV's reign and during the regency, especially after John Law's manipulations of the currencies in support of his famous System (1719–20). These discussions usually mentioned the monetary policy of Nicolas Desmaretz, Louis XIV's last finance minister (1708–15), who ordered a massive devaluation of the French currency in 1709, and the impact of his decision to restore the livre tournois to its intrinsic value through a series of 13 revaluations in 1714. But commentators showed no interest at all in the four debasements ordered respectively by Pontchartrain in 1689 and 1693, and then by Chamillart in 1701 and 1704. This is all the more surprising: Table 1 below shows that Chamillart's tenure in office was the most agitated period in French monetary history before John Law's experiment and, of course, the introduction of assignats during the French Revolution.

Table 1. French debasements under Louis XIV, 1689–1715

Source: Archives des Affaires étrangères, Mémoires et documents, France, 1297, Abrégé du travail fait dans les monnaies depuis l’édit du mois de décembre 1689.

II

One of Chamillart's first decisions when appointed contrôleur général des finances was to audit the royal treasury. Although on paper Louis XIV won the Nine Years’ War, the kingdom had been struggling since the great famine of 1693–4, which killed 10 per cent of the French population (Lachiver Reference Lachiver1991). The return of peace in 1697 failed to bring swift economic growth. The impact of monetary policy, change in the geography of international trade and the introduction of new tariffs conspired against French recovery. Merchants complained about the obstacles to trade caused by the multiplicity of new indirect taxes and internal barriers introduced during the conflict. Also, the harvests were poor and corn had to be imported. The financial situation was not good either: on 6 September 1699, Chamillart established that the deficit for that year would reach 53 million, about half of the gross annual revenue (Esnault Reference Esnault1883).

Although documents about the new minister's early years in office are sparse, evidence suggests that novel ideas were being examined. The creation of a Conseil Royal du Commerce (1700) was an original way of responding to the concerns of merchants and bankers, and of involving these experts in policy making (Schaeper Reference Schaeper1983). On the financial front, Chamillart's personal hostility to the traitants d'affaires extraordinaires, i.e. the financiers who sold royal offices on the king's behalf, meant that the minister was open to alternative methods for raising cheaper credit (Doyle Reference Doyle1997; Félix Reference FÉlix2015). Chamillart was interested in a proposal, inspired by the Amsterdam credit market, to issue rentes mobilières, or bearer notes, that could be traded more easily than the illiquid rentes perpétuelles (royal perpetual loans) (Béguin Reference BÉguin2012). A proposal to establish a bank in Paris, modelled on the Bank of England, was the subject of serious discussions in 1701/2 that involved Madame de Maintenon, Louis XIV's morganatic wife, and perhaps John Law himself (Harsin Reference Harsin1933).

Foreign gazettes reported the progress of these discussions in Versailles and signalled the opposition from influential individuals, such as Harlay, first president of the Parlement de Paris (Chamillart Reference Chamillart1884, i, pp. 93–100). The backing of the bank project by several bankers and merchants was insufficient to overcome the hostility of the administrative and judicial elite whose portfolio was mostly in rentes. Chamillart probably gave up on innovations as the death of Charles II of Spain (1700) led Europe towards the War of the Spanish Succession. From that moment, the finance minister, now also secretary of state for war, had to concentrate on preparing the military campaign. In need of some support, he created two new posts of directeurs des finances, one of which was given to Nicolas Desmaretz (1648–1721). Trained by Colbert himself, who was his uncle, Desmaretz had lived in semi-exile for bribery since 1684 but was consulted by the king's ministers who regarded him as one of the best experts. Recalled to public office, he became one of Chamillart's main advisors on fiscal and monetary policy, and took over the finance portfolio from him in 1708, which he kept until Louis XIV's death (McCollim Reference Mccollim2012).

Projects in favour of banks and paper money continued to reach Chamillart's desk. On one, a secretary seems to have summarised the content of the minister's oral answer: ‘No. Especially since the establishment of the Caisse des emprunts’.Footnote 5 Arguably, the various bank proposals were abandoned in favour of the creation of the Caisse des emprunts (CdE), which John Law, as the reader will remember, mentioned among the reasons for the rejection of his bank project in 1715. As there was indeed a link between the CdE, the operations on the coinage and the issuing of paper money, it is necessary to say a few words about this establishment. Its origins can be traced back to the mid seventeenth century when the government leased out the collection of the salt tax (gabelles) to a powerful company of tax farmers (fermiers généraux) (Dessert Reference Dessert2012). To pay cash advances to the king, the tax farmers raised money by selling bearer bonds known as promesses des gabelles.

In the course of the Dutch War (1672–78), Colbert decided to build upon this private system of credit and, as it were, ‘nationalised’ the CdE by conferring a royal guarantee (1674) (Antonetti Reference Antonetti and Mousnier1985). This arrangement was meant to attract the savings of individuals and communities who, on moral or legal grounds, would not lend money to the financiers or could not freeze their capital. Colbert's immediate successor, who feared a rush on the CdE, decided to reimburse all the promesses (1683–4), which were converted into long-term loans. The management of the CdE was returned to the tax farmers until 1702, when Chamillart decided to guarantee again the promesses des gabelles, to which was now attached an interest of 8 per cent, a substantial increase which says a lot about the growing difficulties France had been experiencing since Colbert's death.

As shown in Figure 2, the beginning of the CdE was rather modest, and this despite Chamillart's demands on each individual tax farmer to buy promesses. In August 1702, money started to flow in: 1,820 bonds (promesses) were sold, more than the total issued in the first five months of its existence. The first payment of interest probably reassured potential lenders. At this date, the balance sheet showed a surplus worth 4.3 million lt. By December, the turnover reached 30 million lt., a sum equivalent to the annual revenue of the English land tax or the combined product of the English excise and customs. Part of the sums collected was immediately used to fund war expenditure. A note dated 26 May 1703 calculated that Chamillart had assigned 4.7 million on the CdE since January. The trésorier général de l'extraordinaire des guerres and the trésorier général de la marine obtained 1.8 and 1.2 million respectively. In third position came Samuel Bernard (1651–1739) who was assigned 464,225 lt. As Europe's single most powerful banker, he came to dominate French remittances between 1703 and 1708 and, as such, became one of Chamillart's main advisors.Footnote 6

Figure 2. Promesses issued by the Caisse des emprunts, March 1702 – October 1704

Various reasons may explain why the CdE was preferred to the bank projects. Apart from its past services, the capacity of this institution to avoid runs was regarded as a substantial advantage which suited the French money market. Like any credit institution the CdE faced the possibility of a liquidity crisis, especially as its deposits were destined for military expenditure. Like a bank, the CdE could respond to credit crunch by raising the interest rate on its bonds or calling upon the tax farmers (acting as de facto shareholders). Yet the French credit institution had several weaknesses. Unlike a bank, the CdE did not have any independent revenue other than the product of taxes already assigned. Since its bonds were cashable every six months the cashier could plan cash flows in advance, but this short-term maturity constantly exposed the CdE to the problem of preference for liquidity. In this respect, the CdE's success meant that the movement of money was substantial. A note about the situation of the CdE sent to Chamillart on 24 September 1703 – he received a cashier's report every evening – calculated that 14.6 million worth of bonds were to reach maturity in the near future: 2.1 million in the last days of September, 5.2 million in October, 3.4 million in November and 3.8 million in December. Given that a year of war cost about 100 million, these sums were not huge but remained significant, especially as the bonds were payable only in Paris.

At the end of September 1703, the total of the sums brought to the CdE since its inception was 51 million and its expenditure 50.6 million. The initial surplus had rapidly shrunk to under half a million (480,522 lt.). On 13 October 1703, for the first time, the balance sheet was negative. Five days later, Chamillart asked Desmaretz to report on the situation and ways to sustain the CdE: ‘I am starting, Sir, to be scared of what I see concerning the Caisse des emprunts; its situation gets worse from day to day and I apprehend that in the end the well might dry up.’Footnote 7 Desmaretz's answer was somewhat reassuring: he explained that current circumstances, in particular the renewal of all the tax farmers’ leases, had squeezed the CdE as the new financiers were cashing promesses to pay their advances to the royal treasury. Desmaretz also pointed out that the public expected a new restamping, and so were hoarding money until they could find a valuable investment.Footnote 8 The tax farmers remained confident that the promesses would sell again in November and that the crisis would be over soon, provided the CdE continued to pay regularly. The prediction proved only half-true as the volume of bonds sold by the CdE did not pick up. The daily balance sheets that have survived show that more money was paid out each day than brought in, and the leakage continued until February 1704. The accumulation of negative balances was a worry but the authorities did not panic. On a daily basis, the lack of funds was relatively small (for instance, 43,744 lt. on 26 November 1703). Payments were met by transfers of coins from the cashier of the tax farms, whose coffers were located in the same building. To ease the pressure, potential new lenders were identified by Desmaretz, in particular foreigners who were offered special facilities and guarantees.Footnote 9

It was in this anxious context that Chamillart, on 25 September 1703, published an arrêt du Conseil (royal order) stipulating that the CdE would accept billets de monnaie until the end of the year. These bills had been circulating for two years, after a new and third restamping (September 1701). Like the two previous operations, its purpose was to fund the new war, which witnessed the reconstitution of the Great Alliance, minus Spain. But there was a hurdle: the time needed for restamping the monetary stock was likely to slow the expected benefits of the operation. Previously, in order to make the transition as smooth as possible, the government had used various techniques which were not fully satisfactory, including the authorisation of both old and new coins for a certain period. This time, Chamillart decided that the receipts traditionally delivered in exchange for the coins brought to the mints would be issued in the form of payments. In other words, the delay between reception of old coins and delivery of new ones formed the basis of a temporary credit through the circulation of the receipts, the so-called billets de monnaie, or mint bills. This development opened the possibility of issuing more bills than coins actually received, or circulating paper money, as the Bank of Amsterdam did with its receipts for cash deposits (Gillard Reference Gillard2004).

It is not clear whether Chamillart expected to use the mint bills to simply anticipate the benefits of the 1701 restamping or to increase the means of payments. There was certainly pressure on him to act in this way. On 5 October 1701, a certain Fabre, probably Joseph Favre, an important merchant and financier in Marseilles who had been appointed councillor to the Conseil Royal de Commerce, wrote the following letter to Chamillart:

As you gave me permission to tell you my feelings on facts that I believe to be important, I must represent to Your Highness that I see a general lack of confidence [discrédit] in Paris that makes all people suffer a lot. The bad situation of the time is the cause of all these … until the increase of the coins has produced its effect. And many people lock up their money for the fear they have of investing it badly … And as I see that the mint bills are as well received as coins, I would believe it an absolute necessity to remedy the present evils, that Your Highness condescend to provide for the king, via the directeur and contrôleur de la monnaie, 3 or 4 million livres tournois in bills of large and small sums, as down payment and by way of advance on the profit His Majesty will derive from this increase … This would produce an even greater effect than if you spread coins amongst the public …Footnote 10

A comment on this letter, which is not in Chamillart's handwriting but may have been dictated by him, rejected the suggestion forcefully; ‘I thank him for his advice and he can be assured that I will not use it, that I have even given very pressing orders to satisfy the public with great diligence. This is the only means to re-establish and preserve credit.’

Chamillart's decision to attach an interest to the mint bills would suggest that the minister, at that time, did not consider the mints’ receipts as a substitute for money but simply an incentive for people to bring their cash to the mints speedily. Nevertheless, the government soon printed more mint bills than coins received. On 1 May 1702 the bills delivered by the Paris mint exceeded net seigniorage by 1 million lt. One year later, on 1 July 1703, the shortfall had risen to 2.3 million lt.

Several mint bills of the earliest issue have survived. They were printed with blank spaces to be filled in. One reads as follows:

Slip

For the sum of nineteen hundred twenty six Livres

fourteen sols that I shall pay in

-------------- to the bearer, value received from Mr LeLong

In coins to be restamped

Done at the Hostel de la Monoye in Paris, the 22 September 1701

Euldes(signed)

On the back, the billet said:

Registered at the Controlle de la Monoye, for the sum of

nineteen hundred twenty six livres fourteen sols

by Us Conseiller du Roy, Controlleur Contregarde of

the said Monoye in Paris, the 22 September 1701.

Boula (signed).

A handwritten note on this bill shows that it changed hands rapidly. On 3 October, it was already in the possession of the Hogguer brothers, key contractors and remitters for the king, who endorsed it to Le Couteulx, one of the largest banking houses in Rouen.

In the first semester of 1703 the volume of outstanding mint bills remained relatively stable at around 2.5 million lt., with a tendency to rise. Signed by Euldes, director of the Paris mint, on Chamillart's orders, the bills were delivered to the bankers and financiers in charge of paying the troops. In May 1703, Bernard had received 1.1 million worth of notes. In July, the volume of bills suddenly increased and by December it had almost tripled to 6.7 million. This was a relatively small sum, represented by only 9,000 bills, for the outstanding bills had been issued in large denominations. As time went by, however, Euldes accepted requests from holders to have their bills cut, a move which did not please Chamillart. By the end of 1703, two-thirds of the outstanding bills (6,050) were for 500 lt. or under. Almost half of these notes were worth only 150 lt. (or less), a sum equivalent to the annual revenue of a peasant family. In other words, both the volume of mint bills and their velocity had increased in the last half of 1703.

Although the operation looked like a success, Chamillart decided to terminate this first experiment with paper money. Following the announcement that the third restamping would be closed at the end of 1703, an arrêt du Conseil (2 December 1703) ordered the redemption of all the mint bills. The small denominations up to 150 lt. were to be repaid as a matter of urgency and were in effect redeemed. The holders of larger notes were offered the alternative of immediate repayment or 8 per cent interest if they converted their bills to promissory notes of the tax farmers (indirect tax) or the general receivers (direct tax), payable either in April or July 1704. With the exception of a few individuals who asked special permission to hold on to their mint bills, the outstanding bills were all redeemed.

If Chamillart ever received praise for his financial policy, it was on 17 January 1704 when a sieur Du Breuil wrote to him that:

the last two declarations you have published on the mint bills have absolutely re-established confidence [crédit]. That is no paltry service you have rendered to the state, Sir, because trade on the part of merchant bankers was entirely ruined. We see by these acts the superiority of your genius and everyone knows that this is your work.

The letter added, however,

But were it possible, Sir, to stop these increases and decreases of the coins with which the public are threatened each month, it would be one of the most important services than one could render to the state because, Sir, that is the cause of infinite disorders in the kingdom through the suspension of trade in all the provinces … it would be a hundred times better to resort to any other means, whatever it might be, than to use this one to procure some profit to the king.Footnote 11

III

Du Breuil certainly misread Chamillart's intentions. Only a few months elapsed before the minister ordered the fourth and last restamping of Louis XIV's reign. Uncharacteristically, the decision was not made public in the autumn but in May and enforced from 1 June 1704. Chamillart's early move probably reflected problems in gathering funds for the new military campaign. In the course of 1703, the difficulties of the CdE and the rising volume of mint bills reflected a worsening of the fiscal situation. By now, payments to financiers and bankers were severely delayed as the sale of royal offices and annuities dragged on. Among them, Samuel Bernard had advanced no less than 20 million on behalf of the government. He regularly urged Chamillart to maintain a flow of cash in his direction to sustain the complex traffic of bills of exchange upon which he and his correspondents across Europe relied to borrow and remit money to French troops. As Rowlands (Reference Rowlands2012) rightly argued, at this point the system of assignations on the revenue from affaires extraordinaires was dysfunctional, but measures had already been implemented to address this issue.Footnote 12

Difficulties were partly a consequence of the shortage of money in France. In this respect, the failure of the fourth restamping transformed a very difficult situation into a nightmare. As Table 1 shows, over two years (1704–6) the French mints received only 175 million lt. worth of coins to restamp, barely half the coins brought during the 1701 operation on the coinage (321.5 million), which itself was already down by about a third on the restampings of 1689 and 1693. As a result, between 1704 and 1709 France waged war with a stock of legal coins at its lowest ever level. Overall, the distribution of coins among the different mints did not change significantly. The four major mints – Paris, Lyon, Rennes and Rouen – still received between 54 and 60 per cent of the old coins restamped in the kingdom. Yet in volume the money crunch was dramatic. The Paris mint had worked 170 and 140 million lt. worth of coins in the course of Pontchartrain's two restampings as against 103 (1701) and 65 million (1704) under Chamillart. It is hardly a surprise, then, that bankers and financiers were complaining about the scarcity of money and the rising interest rate.

Since all the mints experienced a formidable drop in the coins brought for restamping (between 30 and 74 per cent), the money crunch probably had common causes. Traditionally, the authorities blamed money shortages on the export of coins. In a memorandum written to Marlborough, Huguetan explained that the failure of the 1704 restamping resulted from the accumulated dispatch of coins to Bourbon troops abroad, which he estimated at 70 million lt. per year, of which half (32 million) were destined for Italy.Footnote 13 This analysis – if not the figures – is partly confirmed by observations from Chamillart and Desmaretz on letters and memoranda they received. About the shortage in Lyon, both men agreed that considerable sums had been shipped to Italy, and this despite contracts with Genevan bankers stipulating that remittances should only be effected by bills of exchange (Lüthy Reference LÜthy1959). But the disruption of war, the impact of debasements on foreign exchange rate and emergency situations meant that shipping money out of the country was, at times, the cheapest, fastest or even only solution available.Footnote 14 As was also the case for British remitters to Germany and Spain (Graham Reference Graham2015), French bankers struggled when they could not map out their operations on the basis of established trade networks.

But other causes contributed to the monetary difficulties of Lyon, where the mint under Pontchartrain had restamped as much as 10 per cent of the French money stock, a share now halved to 5 per cent. Part of the problem was interruption of the silver supply (Morineau Reference Morineau1985). During the Nine Years’ War the city's merchants and bankers, and the manufacture of cloth embroidered with silver, had relied on Spanish metal shipped via Barcelona–Genoa–Marseilles (Courdurié Reference CourduriÉ1981). After the death of Charles II of Spain this route was suddenly shut. In Lyon the 1701 restamping brought only 17.4 million worth of coins as against 42 and 48 million previously. In this respect, the defection of Savoy, although a minor state, was a great setback to the French military and financial operations (Storrs Reference Storrs2008). Also, in 1704, England and Holland agreed to coordinate their economic policy and prohibit trade with France, which affected the cost of remittances. At the same time, the benefits of the recent union of the French and Spanish thrones under the Bourbon dynasty were hampered by domestic divisions and conflicting national interests (Lévy Reference Levy1969; Dubet Reference Dubet2009).

These problems were not the sole reasons for France's monetary difficulties. In a monarchy where the king enjoyed absolute power and the right to fix the value of coins, few dared break a taboo and write, as Desmaretz did in 1703, that ‘all these causes cannot have produced the disappearance of all the coins which have not made their way to the mints in the third restamping. It is highly likely that a substantial portion of the coins, and perhaps the largest, stayed in the pockets and safes of individuals.’Footnote 15 This is also Dessert's assumption (Reference Dessert1984). One way or another, the king's subjects, in particular the wealthy, evaded the impact of royal policy. The apparent confusion of the legislation, which retracted, postponed or altered monetary decisions, was probably less a reflection of inconsistency in Versailles’ approach than of ad hoc adjustments to the public responses and, of course, the impact of military campaigns on confidence.

Estimating the volume of coins exported and hoarded is problematical. The success of Desmaretz's recoinage in 1709 is an indication that observers did not exaggerate when they argued that there was still plenty of money in France. In the course of 18 months, between May 1709 and December 1710, the mints delivered coins worth twice the sums brought in 1704. Lyon's mint hit an all-time record with 49 million. The trading opportunities with the Spanish empire were starting to pay off as French merchants and privateers now had a firm grip on the South Sea trade. Further to agreements with Madrid concerning the payment of the Spanish king's tax on specie imports (indult), cargoes full of Peruvian silver – a trade which took on average 18 months – were now authorised to return directly to Atlantic French harbours, like Saint-Malo, and even to Marseilles on the Mediterranean Sea (Dahlgren Reference Dahlgren1909; Lespagnol Reference Lespagnol1996). Yet it is difficult to believe that the increase in the volume of coins produced in 1709 over 1704, worth 200 million lt., and weighing about 15,000 tons, suddenly arrived from South America or were imported back into France from abroad. As we will see, Bernholtz's analytical model of inflation provides a smart solution to the flows of money to the mints.

In the meantime, the failure of Chamillart's two restampings had considerable impact. According to Huguetan, the interest on money rose to 25 per cent in July 1704. On 6 August, Bernard wrote an alarming letter to Chamillart saying that ‘affairs become difficult to a point that it is impossible to express; it is not possible to receive [any shilling] from the best payers; it is not possible to find [one pence] at any price, nor any occasion to get any credit’. Seeking a remedy, Bernard declared: ‘I don't know any other than to make the mint bills legal tender, in one way or another.’Footnote 16 The CdE was a collateral victim of the money crunch. In May the balance sheets were once again negative. In August, news of the French rout at Blenheim caused a financial run. Guiguou, the treasurer in charge of the CdE, informed Chamillart that he had only 20,000 to 25,000 écus left (c. 80,000 lt.) and could not carry on paying as his colleague Bartet, who held the caisse des fermes, refused to support him any longer.Footnote 17 On 13 September, Chamillart informed Desmaretz about the ‘furious rate at which money is withdrawn from the caisse des emprunts; it is too much to be overwhelmed from so many different quarters; I beg you, that you, with Mr Poulletier, find 200 or 300,000 francs for this caisse. There is not a moment to lose for that purpose.’Footnote 18 But money was nowhere to be found. An arrêt du Conseil suspended payments from 17 September 1704 until 1 April 1705.Footnote 19

A solution to the crisis was elaborated in consultation with the key actors. In December, Chamillart had a meeting with the main bankers to whom he disclosed crucial information about the financial situation of the crown. Three steps were taken to restore confidence. First, income from a 10 per cent increase of all indirect taxes collected by the tax farmers was assigned to the CdE; second, to dissuade lenders from requesting payment of their promesses, the interest was increased by 2 points to 10 per cent; third, Euldes was to issue new mint bills that would be legal tender, permitted to circulate only in Paris, and to which would be attached a 7.5 per cent interest. As promised by the government, the CdE resumed its payments on 1 April 1705. For two months confidence remained low: in April and May payments out of the CdE exceeded its revenue by 4.6 million and 1.4 million respectively. What mattered, however, was that owners of promesses accepted to be paid their capital partly in cash and partly in the new mint bills. The main bankers and financiers certainly played a crucial role in helping restore confidence in the CdE by circulating the new bills. Although the CdE's monthly surpluses were not brilliant, by the start of 1706 its situation had improved significantly. While Rowlands is deeply critical of the whole experience, the second issue of mint bills, which built upon the previous one, was a complete success. It overcame the liquidity crisis of 1704 and saved the CdE. It helped turn the page on Louis XIV's bitter defeat in Bavaria by funding the largest military deployment since the beginning of the war.

IV

It is not possible here to analyse in much detail the history of the second issue of mint bills, from their initial appearance in 1704, to their progressive conversion between 1707 and 1709, and their final demonetisation in 1712. Figure 3, which plots data about the market value of mint bills against coins at different dates, shows that the whole experience can be divided into three main phases. As John Law was only too keen to acknowledge later, in the first 18 months of their existence the successful introduction of the new bills confirmed that paper money was a workable solution to overcome the economic and financial evils caused by specie shortages in wartime. ‘This is evidenced’, commented Law, ‘by the success of mint bills. This project … has been received for some time in trade on the same footing as coins’ (Harsin Reference Harsin1934, ii, pp. 18–19). The new bills were such a success that destroying their credit became Huguetan's obsession after he defected to the Allies in 1705. Bernard's former associate managed to convince Marlborough that he should attack the new monetary instrument by renewing prohibitions on Dutch merchants and bankers who traded with France in bills of exchange and, worse, according to Huguetan, in mint bills.

Figure 3. Promesses paid out of the Caisse des emprunts, April 1705 – April 1706

Initially, the parity between the coin and paper currencies was banded, and this thanks to Chamillart's orders to the traitants that their cashiers in Paris buy mint bills with the revenue from affaires extraordinaires. Although our figures indicate an 8 per cent loss of paper money against coins as early as July 1705, a contract signed in November between Chamillart and the Hogguer brothers for remitting money in the 1706 campaign indicates that leading financiers regarded mint bills as equivalent to coins. But even at a loss of 8 per cent against specie, the new monetary instrument was a relatively cheap method of funding the war deficit. Against Versailles’ expectations, however, the 1706 campaign was a complete disaster, which increased financial difficulties. For instance, the failure to capture Turin and neutralise Italy suddenly opened the south of France to foreign invasion, thus drying up a line of credit from Italian bankers whose operations were backed by the nearby états provinciaux of Languedoc, i.e. provincial tax institutions. Between August and November 1706, the premium of coins over mint bills rose from 20 to 60 per cent. Among the victims were the Hogguers who had to abandon remittances (Lüthy Reference LÜthy1959). A spate of royal orders was meant to reduce the growing gap between specie and paper, including the appointment of Desmaretz in February 1708, the effect of which is noticeable in Figure 4, but they failed to reverse the trend.

Figure 4. Value of money bills against coins (%)

Although inflation and defeat suffice to explain the mounting criticisms of Chamillart, primary sources show that he had a solid grasp of the problems and was able to make independent judgements. Whether or not their grateful letters to Chamillart are to be read as expressions of polite deference for a minister who held the highest responsibilities ever bestowed by Louis XIV on one person, the bankers he invited to his residence to discuss again with him the problem of paper money had only praise for his deep understanding of money matters. True, Chamillart failed to find a satisfactory solution to a monetary experience which got out of hand. But this was an extraordinary situation: no country had ever experienced the effects of the sustained injection of paper money. Given the military and fiscal constraints, neither the technocrats nor the wider merchant community were able to offer accurate, clear or workable proposals for tackling inflation. Desmaretz himself, certainly one of the best experts, acknowledged the challenge. In a major report where he summarised the proposals sent to the government, Chamillart's advisor admitted in May 1706 that the mint bills had become ‘the most difficult financial matter that has ever presented itself’.Footnote 20

Chamillart, who read and, on more than one occasion, annotated the projects he solicited and received, was well aware of the three main causes of depreciation. Too many mint bills had been issued with limited collateral. On 1 December 1705, the profit on the fourth restamping was 9.2 million as against 83.6 million lt. of outstanding mint bills. At the end of 1706 some 180 million lt. worth of mint bills circulated in Paris, a sum equivalent to the costs of one military campaign. By contrast with England, where each issue of exchequer bills was fixed by Parliament (Dickson Reference Dickson1967; Kleer Reference Kleer2015), the number of French mint bills printed and distributed was unknown. Inevitably, lack of trustworthy information fuelled rumours and eroded confidence. The initial success of the mint bills owed a lot to restoring trust within the financial community. For instance, in the summer of 1704, at the height of the credit crunch, Bernard had bluntly refused to honour a bill of exchange drawn on him and presented for payment by the tax farmers’ cashier because the latter had refused to accept a payment by compensation, i.e. in deduction of a note Bernard owned on him.Footnote 21 In this context, the introduction of new monetary instruments backed by a new restamping, and combined with a 10 per cent tax increase, had been regarded as the only quick fix to the liquidity crisis.

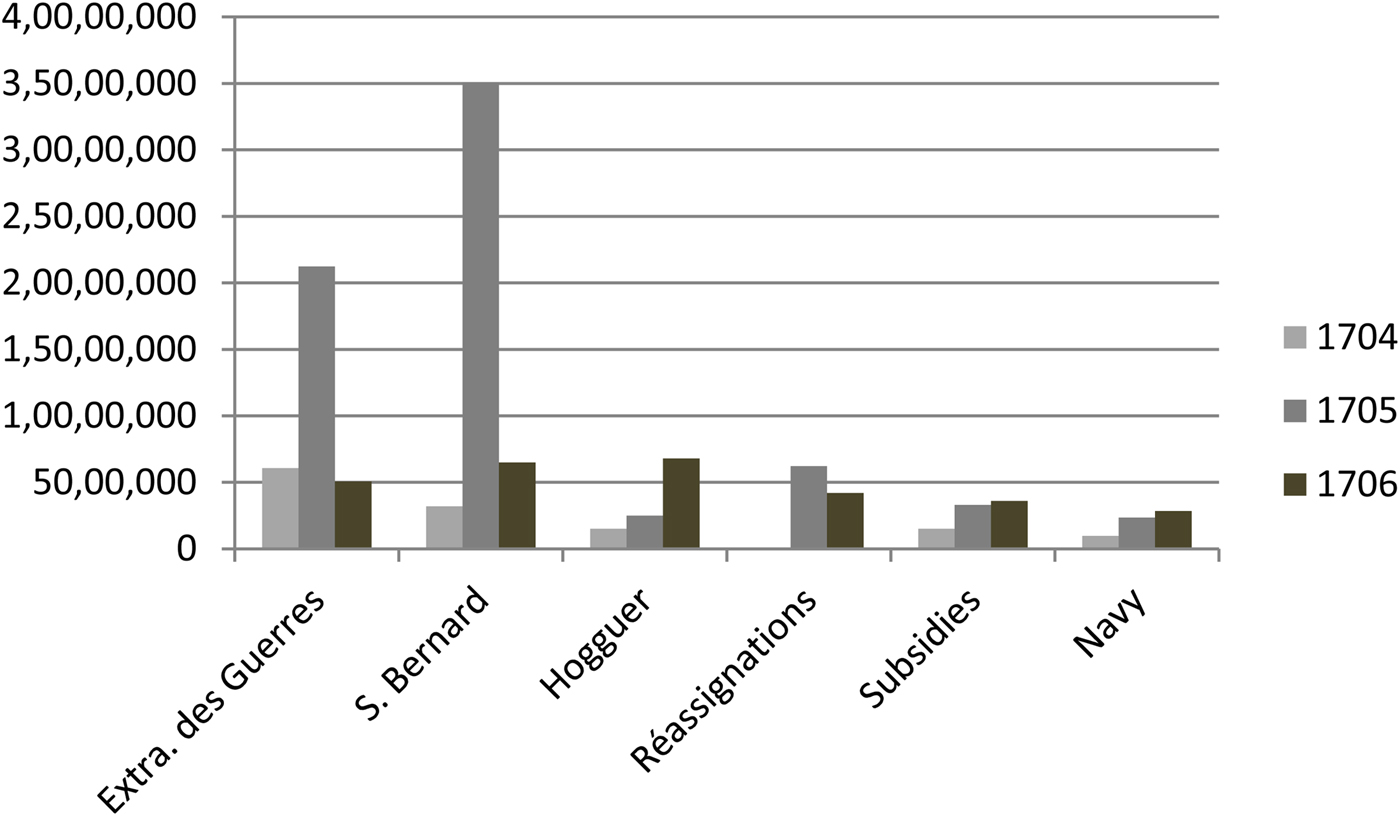

By 1706, such adjustments were insufficient to sustain the mass of paper money. As Figure 5 shows, the general treasurers of the army, the bankers in charge of remittances and the military suppliers were the main recipients of mint bills. The new credit facility had its limits, though, because the financiers could not operate with paper money only. In particular, every three months they needed to gather large amounts of cash to settle their accounts with their correspondents and creditors at the Lyon fairs (Sayous Reference Sayous1938; Lüthy Reference LÜthy1959; Lévy Reference Levy1969; Rowlands Reference Rowlands2012, Reference Rowlands2014). In need of specie, financiers and bankers had to sell bills for coins. The more mint bills they cashed the more widely these bills circulated in Paris, the only place where they were allowed as payments.

Figure 5. Principal posts of expenditure financed by mint bills, 1704–6

Inevitably a secondary market blossomed. Indeed, there was a demand for bills. Since they were legal tender, the notes could be used by creditors to pay off their debts or to apply the threat of a repayment in depreciated bills to obtain better conditions from their lenders.Footnote 22 People who had trials pending before a court could also use mint bills when asked to give a deposit (consignation). In this respect, not unlike John Law's System, the experience of the mint bills may have had some positive impact on activity (Faure Reference Faure1977; Jambu Reference Jambu2013). This said, Chamillart and Desmaretz, like most of their successors in the eighteenth century, were reluctant to let the private market determine the price of bills. They loathed the brokers and a new group of individuals, the so-called agioteurs (jobbers), whom they blamed for the depreciation of paper money. In the spring of 1706, Chamillart imprisoned several jobbers in the Bastille. As rumours about speculation developed, he warned prominent financiers of terrible penalties if he learnt that they engaged in trafficking.Footnote 23 But severity only contributed to the depreciation of bills against specie.

As Desmaretz admitted in the May report he wrote for Chamillart, the outright suppression of bills was not a viable solution because they remained a useful and necessary resource to fund the war deficit.Footnote 24 The key question was to decide whether the advantages of the bills were worth their costs. Arguably, the answer was both technical and political. In collaboration with the best experts, Chamillart explored various ways of fighting depreciation by reducing the number, widening the circulation and improving the liquidity of mint bills. At the start of 1706 a royal declaration had already tried to restore confidence by stating the king's commitment to redeeming the bills after the war. But bad news from the front constantly destroyed hopes of a foreseeable peace. In June of the same year it was announced that no more notes were to be issued. In September, a policy of absorption by conversion was devised. As in 1703, the mint bills could be exchanged for promissory bills of the tax farmers (25 million lt.) and the receivers general (25 million lt.), or used to purchase new issues of royal loans (18 million lt.).

Illiquidity was another cause of the depreciation of mint bills. In particular, they could not be employed for paying taxes. Many contemporaries complained about a legal tender which the king rejected for himself. The reasons for this apparent contradiction were twofold. The idea of allowing payment of taxes in bills looked like opening Pandora's box. It would jeopardise cash payment of the interest on perpetual bonds, which constituted a substantial portion of the revenue of many families in Paris, in particular the elite of office-holders. In other words, it could be the spark of a revolt in Paris, as in the Fronde of 1648. The government also feared that tax receivers would hoard cash and send notes to the Treasury, as happened in England in the third issue of exchequer bills with the help of the London goldsmiths (Kleer Reference Kleer2015). If the Bank of England, in tandem with the Treasury, was capable of exerting pressure on fiscal agents, France lacked a central institution to monitor the activities of the receveurs généraux des finances and those receivers who, under them, collected direct taxes across the kingdom. This problem became acute only after Chamillart, further to an important meeting with bankers, in May 1707 ordered that all payments would be made with a portion of bills and throughout the kingdom. The responses from the provincial authorities and the merchants were so unanimously hostile that not only was the decision postponed until the end of that year but it also probably cost Chamillart his post as finance minister. As the crisis unfolded, Chamillart became restless and authoritarian. In September 1707, he wrote a fiscal report for the king and asked for full powers, in particular in the area of economic policy where he had constantly been thwarted by Pontchartrain and his son.Footnote 25

As shown in Figure 4, all these measures certainly helped fight inflation. But the monarchy was so short of cash that concessions were governed by urgent needs and, as a result, they were often double-edged. For instance, the benefits of conversion into other assets were cancelled by the suppression of the interest paid on the outstanding mint bills. Meanwhile, the costs of remitting money abroad snowballed. The services of the bankers who contracted remittances became unsustainable. On top of the losses resulting from the debasement of the livre tournois, they had to charge the king for the costs of selling mint bills for coins. Moreover, as the royal treasury did not pay them in advance, bankers had to charge interest for securing loans on the international money market, to which were added the commissions of intermediaries. In addition, news from the battlefield continued to play a crucial role. As far as public confidence was concerned, the fall of Lille (1708) wiped out the benefits of Desmaretz's appointment. As with the Hogguers in 1706, the depreciation of the mint bills threatened Samuel Bernard's capacity to continue borrowing on the international market. In spring 1708, at the Lyon fair, he was unable to reach an agreement with his principal creditors, a dire situation which unleashed the second major financial crisis of the war (Lüthy Reference LÜthy1959; Lévy Reference Levy1969; Rowlands Reference Rowlands2012, Reference Rowlands2014).

A last attempt was made to preserve the principle of paper money without suffering its side effects, and this through the establishment of a bank. Several projects were submitted to the new minister. They all aimed to reduce the volume of mint bills or consolidate them into other assets. At the start of 1709, Bernard's bank proposal was agreed by the king but almost immediately abandoned by Desmaretz. The alleged failure of one of Bernard's partners to gather his share of the capital of the bank was probably less relevant than a staunch opposition, in particular from the royal intendant in Lyon, which shook Desmaretz's trust in the scheme (Boislisle Reference Boislisle1874–97, iii, pp. 646–51; Harsin Reference Harsin1933). As Rowlands contends, it was probably not workable. Desmaretz decided that the suppression of the mint bills was the only viable option. To this effect, a fifth and last debasement was ordered by the king in May 1709. This time the operation was performed by means of a full recoinage. To obtain new minted coins, the king's subjects were required, as usual, to bring their old coins to the mint but also mint bills amounting to one-sixth of the value of their coins.

Despite the Paris Parlement's astute observations that the substantial increase in the value of the coins and the total loss of the mint bills would be extremely costly to the king's subjects, the operation went ahead. Supported by the arrival in Saint-Malo of ships carrying 30 million worth of silver which Desmaretz managed to borrow, the 1709 recoinage was relatively effective, especially given the dire context of the Great Winter. Bernholtz's analytical model explains the apparent contradiction of people now bringing to the mints their money and bills, as would happen again in 1718, despite the clear loss. Whereas, in the first stage of Chamillart's policy of debasement, the co-existence of two currencies of different nominal value had set in motion Gresham's law, which was further reinforced by the introduction of mint bills, in the second stage paper money inflation had reduced the value of mint bills to the point that Thiers’ law applied and people were keen to bring in their hoarded coins (Berholtz Reference Bernholz2003, p. 132). In effect, after years of war and in the context of money shortages, many of the king's subjects badly needed specie as the bills had lost most of their value.

Desmaretz's operation, though, was only a partial success: out of the 72 million lt. of mint bills still in circulation only 37 million were absorbed in the recoinage. New opportunities for converting the remaining mint bills into promissory bills or capital of loans had to be offered, until their demonetisation in 1712.Footnote 26 Meanwhile, Desmaretz tried to persuade the hoarders of old coins to bring their savings to the mints, in particular by offering a better price and removing the need to include mint bills. He also attracted silver piasters to France by offering a higher price to specie (surachat). Thanks to these measures, the legal stock of money was reconstituted to its pre-war level in 1715. Yet, considered as a process, the recoinage was unable to put an end to the credit crunch, war deficit and inflation overnight. In fact, while Desmaretz suppressed the mint bills on the one hand, he drew heavily on the CdE on the other hand. The promesses des gabelles issued rose from 44 to 140 million between 1707 and 1714, a level close to Chamillart's mint bills. At the end of the war, the CdE institution was on the brink of collapse. So too was Desmaretz's Caisse Legendre (1710) which issued receiver general's bills, or anticipations of future tax revenue. As with the mint bills, managing this growing volume of monetary instruments became harder and costlier for lack of adequate collateral. Desmaretz's introduction of a new universal tax on wealth, the dixième (1710), was a very courageous move but it came too late and its product was disappointing (Bonney Reference Bonney1993; McCollim Reference Mccollim2012). Like the mint bills, payment of the interest on promesses had to be postponed in 1710, and capital repayment could only be met by secret new and larger issues which were discounted by bankers and financiers at great loss. At Louis XIV's death, in 1715, inflation had reached new highs: the short-term debt in bonds and other monetary instruments was over 800 million, a sum broadly equivalent to the costs of four military campaigns (Desmaretz Reference Desmaretz1715). One might argue, therefore, that Desmaretz, whose administration has been praised by historians, did not do much better than Chamillart. This is hardly a surprise: after all, they worked hand in hand until the political pressures of military and fiscal crises parted them.

V

An anonymous, able and hostile commentator on the experience of mint bills (and banks in general) summarised the whole monetary experience with a riddle: ‘the politician would say to the financier that without the help of these bills we could not have started nor continued the enterprises we have undertaken, and the financier would ask if it would not have been better to wish not to have started them, since it is not possible to sustain them any longer’.Footnote 27 In many respects, this article confirms this analysis. Mint bills made it possible for France to pursue the war effort but, at the same time, they created new problems. In marked contrast to John Law's contention that the mint bills’ chance of success depended on the proper management of a necessary resource, the anonymous observer insisted on the incompatibility between absolute power and paper money. In one case the failure is attributed to institutions; in the other, it points to individual responsibility, in particular, as Rowlands argued, the personal limitations of Chamillart.

My own analysis shows that Chamillart, regardless of his lack of success in the realm of finance and his misfortunes on the battlefield, was not as helpless a figure as his poor reputation would suggest (Pénicaut Reference PÉnicaut2004). Our anonymous commentator, who scathingly wrote that only Louis XIV failed to see how stupid Chamillart was, would have been surprised if he had seen a letter from the minister to the king dated 16 October 1706. In this letter, written six months after the French defeat at Ramillies, and while he was preparing the next campaign, Chamillart reminded the king that he had advised him in 1703, on the grounds of financial exhaustion, to make peace at the expense of Spain; and that after Blenheim he had proposed the ‘introduction of the mint bills, not as a great relief, but as a necessary evil’. Chamillart added:

I took the liberty to tell Your Majesty that [the evil] would become irremediable if the war forced [us] to make such a great number that the paper would take over the money. What I predicted has happened, the disorder they have produced is extreme; far from considering them as a new means of getting more help, one must necessarily think of reducing it at a time when there is a dearth of resources on all sides.Footnote 28

This letter gives rise to an array of questions about the nature of power in the absolute monarchy, a matter of lively academic discussion, and the making of royal policy under Louis XIV. On paper, Chamillart was the most powerful Bourbon minister ever; in practice, it appears that neither his personal advice about the war nor his warnings about abusing the facility of mint bills were seriously listened to. To resolve this apparent paradox and account for the difficulties encountered during Louis XIV's last wars, historians have recently argued that the ministers appointed later in his reign were not as able as Colbert and Louvois, their illustrious predecessors (Sarmant and Stoll Reference Sarmant and Stoll2010; Stoll Reference Stoll2011). In the light of recent research on the early modern state in France (Collins Reference Collins2009) or military strategy and the old problem of cabinet policy (Cénat Reference CÉnat2010), it seems that more investigation needs to be undertaken concerning the formation of French fiscal policy and decision-making under Louis XIV, paying attention to the internal dynamics of the Conseil du Roi, the king's entourage, and the various pressure groups in Versailles.

Louis XIV's political decision to pursue war was the main reason for the introduction of mint bills. The initial success of this paper money partially validates the mismanagement thesis advanced by John Law and Guy Rowlands. But at the same time Law's own failed experience shows that printing money (and devaluating currency) was much easier than managing the inflationary bias of political systems. As a matter of fact, the men in charge of finance tried their best and sought the help of the financing and banking community to make the most of Chamillart's first experiment with paper money. But maintaining confidence in paper against specie was a thankless task in the face of recurrent military defeats, given the absence of constraints on the power to print notes according to needs, and the lack of robust collateral in the form of adequate fiscal revenue and an affordable credit system. For the anonymous commentator, the true power of a king rested on his sovereign right to tax his subjects and not on determining the value of paper money, which depended on public trust. Paradoxically, as Bayard (Reference Bayard1988) and Dessert (Reference Dessert1984) have demonstrated, the Bourbon kings preferred not to tax their elites and used other methods to tap the wealth of their subjects, in particular through exploitation of privilege. This contradiction in the relationship between the king, the privileged elites and the rest of his subjects remained at the heart of Old Regime France, and is rightly considered a major structural weakness and a cause of the ultimate collapse of the absolute monarchy. Yet it is questionable whether any ruler or polity would have embarked upon war without a sense of their own strengths or had they known that the conflict would drag on for a decade or more. Louis XIV's thirst for glory, his personal authority and the sheer size of his kingdom meant that he was able to pursue war, fatigue and divide his enemies, avoid financial meltdown, escape ultimate defeat and, even, win Spain and its colonial empire for his dynasty. To be sure, he left a heavily burdened kingdom to his successor, but one which had the potential to reap the benefits of the Spanish Succession. For better or worse, that is another story.