Assessment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in schizophrenia is clinically important because of the high prevalence of depression and suicidality in schizophrenia and its effect on functioning and quality of life.Reference Andrianarisoa, Boyer, Godin, Brunel, Bulzacka and Aouizerate1 The relationship between psychotic and affective symptoms has been central to the dilemma of psychiatric classification.Reference Buckley, Miller, Lehrer and Castle2 It has been suggested that some positive symptoms, especially delusions, may be specifically associated with MDD via cognitive biases.Reference Vorontsova, Garety and Freeman3 Schizophrenia is also associated with increased somatic comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome (MetS), a general metabolic disturbance that has been identified as twice as high in patients with schizophrenia compared to the general population,Reference Godin, Leboyer, Gaman, Aouizerate, Berna and Brunel4 and chronic low-grade peripheral inflammation that has been associated with cognitive impairment in schizophrenia.Reference Bulzacka, Boyer, Schürhoff, Godin, Berna and Brunel5 Antipsychotics themselves produce extrapyramidal side-effects (particularly bradykinesia, blunted affect and verbal delays which may be confused with the psychomotor retardation of depression.Reference Addington, Mohamed, Rosenheck, Davis, Stroup and McEvoy6 People with schizophrenia are also prone to addictive behaviour, some of which may also produce depressive symptoms.Reference Rey, D'Amato, Boyer, Brunel, Aouizerate and Berna7 There are no current guidelines for the treatment of MDD in patients with schizophrenia. For example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines make no specific recommendation for the treatment of MDD cooccurring in SZ.Reference Taylor and Perera8 Two recent meta-analyses have concluded that antidepressants may be effective in the treatment of MDD in schizophrenia; however, evidence was mixed and conclusions must be qualified by the small number of low- to moderate-quality studies.Reference Gregory, Mallikarjun and Upthegrove9, Reference Helfer, Samara, Huhn, Klupp, Leucht and Zhu10 However, there is a robust and current debate on the effectiveness of add-on antidepressant therapy in patients with schizophrenia and MDD. Schizophrenia is also associated with increased somatic comorbidities, including MetS, a general metabolic disturbance that has been identified as twice as high in patients with schizophrenia compared to the general population,Reference Godin, Leboyer, Gaman, Aouizerate, Berna and Brunel4 and chronic low-grade peripheral inflammation that has been associated with cognitive impairment in schizophrenia.Reference Bulzacka, Boyer, Schürhoff, Godin, Berna and Brunel5 Depression has been associated with metabolic disturbances in schizophrenia including MetS parameters,Reference Godin, Leboyer, Schürhoff, Boyer, Andrianarisoa and Brunel11 and chronic peripheral inflammation has been associated with MDD and antidepressant consumption in patients with schizophrenia.Reference Fond, Godin, Brunel, Aouizerate, Berna and Bulzacka12, Reference Faugere, Micoulaud-Franchi, Faget-Agius, Lançon, Cermolacce and Richieri13

The objectives of the present study were to determine the prevalence and associated factors of MDD in schizophrenia, to determine if patients with schizophrenia treated with antidepressants had lower depressive symptoms levels compared with those without antidepressants and to determine the prevalence and associated factors with remission in patients with schizophrenia who were administered antidepressants.

Method

Study design

The FACE-SZ (FondaMental Academic Centers of Expertise for Schizophrenia) cohort is based on a French national network of ten Schizophrenia Expert Centres (Bordeaux, Clermont-Ferrand, Colombes, Créteil, Grenoble, Lyon, Marseille, Montpellier, Strasbourg and Versailles), set up by a scientific cooperation foundation in France, the FondaMental Foundation (www.fondation-fondamental.org), and pioneered by the French Ministry of Research to create a platform that links thorough and systematic assessment to research.Reference Schürhoff, Fond, Berna, Bulzacka, Vilain and Capdevielle14

Study population

Consecutive, clinically stable patients (defined by no admission to hospital and no treatment changes during the 8 weeks before evaluation) with a DSM-IV,15 Text Revision diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were consecutively included in the study. Diagnosis was confirmed by two trained psychiatrists of the Schizophrenia Expert Centers network. All patients were referred by their general practitioner or psychiatrist, who subsequently received a detailed evaluation report with suggestions for personalised interventions.

Data collected

Patients were interviewed by members of the specialised multidisciplinary team of the Expert Center. Diagnoses interviews were carried out by two independent psychiatrists according to the Structured Clinical Interview for Mental Disorders (SCID v1.0).

Depression and remission under antidepressant definitions

Current depressive symptoms were evaluated by the Calgary Depression Rating Scale for Schizophrenia (CDRSReference Addington, Addington, Maticka-Tyndale and Joyce16, Reference Lançon, Auquier, Reine, Bernard and Toumi17). A score of ≥6 is considered as a current major depressive episode. The CDRS is the most widely used scale for assessing depression in schizophrenia. It has excellent psychometric properties, internal consistency, interrater reliability, sensitivity, specificity and discriminant and convergent validity.Reference Addington, Addington, Maticka-Tyndale and Joyce16

There is no consensual definition to date of remitted MDD in patients with schizophrenia to date. As the present study was an ecological/observational study and that all patients were on stable medication for more than 8 weeks, non-remitted MDD was defined as current antidepressant treatment and a CDRS score ≥6 (current MDD episode) at the time of the evaluation.

Sociodemographic, clinical and treatment variables

Information about education level and illness duration was recorded. As the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is not suited to differentiate the different delusions and hallucinations,Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler18 delusions hallucinations and negative symptoms were evaluated by the SCID v1.0Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams19 as well as current cannabis and alcohol misuse disorder (the presence of at least two symptoms among the 11 explored in DSM-IV indicates an alcohol misuse disorder). PANSS total score was only used for the description of the sample characteristics. Insight was measured by the Birchwood Insight Scale score, a brief self-reported measure.Reference Birchwood, Smith, Drury, Healy, Macmillan and Slade20, Reference Cleary, Bhatty, Broussard, Cristofaro, Wan and Compton21 Current daily tobacco smoking was self-reported. Ongoing psychotropic treatment was recorded as well as other medication. The antipsychotic treatments were classified according to their Anatomical-Therapeutic-Clinical (ATC) class. First-generation antipsychotics (FGA) were defined by ATC classes N05AA–AC (phenothiazines), NO5AD (butyrophenones) and NO5AF (thioxanthenes). Second-generation antipsychotics were defined by ATC classes N05AH (diazepines, oxazepines, thiazepines and oxepines) and NO5AL (benzamides). Chlorpromazine equivalent dosages were calculated according to the minimum effective dose method.Reference Leucht, Samara, Heres, Patel, Woods and Davis22 All patients were on stable medication for more than 8 weeks and treated by antipsychotics.

Measurements

A blood draw for routine blood exam was performed and triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and total cholesterol as well as glucose (if patients confirmed fasting for at least 10 h) were collected. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured with an assay using nephelometry (Dade Behring), blinded to schizophrenia status.

MetS definition

Sitting blood pressure and anthropometrical measurements were recorded in the Expert Centers. Two blood pressure measurements were made 30 s apart in the right arm after the participant had sat and rested for at least 5 min. A third measurement was made only when the first two readings differed by more than 10 mm Hg. The average of the two closest readings was used in the analysis. Waist circumference was measured midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest with the patients standing. This was performed with a tape equipped with a spring-loaded mechanism to standardise tape tension during measurement. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Overnight fasting blood was collected for metabolic profiles analysis. Fasting levels of serum triglyceride and fasting plasma glucose were measured by an automated system, and serum HDL cholesterol level was measured by electrophoresis. The diagnosis of MetS was defined according to the modified criteria of the International Diabetes Federation,Reference Alberti, Zimmet and Shaw23 which requires the presence of three or more of the following five criteria: high waist circumference (>94 cm for men and >80 cm for women), hypertriglyceridemia (≥1.7 mM or on lipid-lowering medication), low HDL cholesterol level (<1.03 mM in men and <1.29 mM in women), high blood pressure (≥130/85 mmHg or on antihypertensive medication) and high fasting glucose concentration (≥5.6 mM or on glucose-lowering medication).

Ethical concerns

The study was carried out in accordance with ethical principles for medical research involving humans (World Medical Association, Declaration of Helsinki). The assessment protocol was approved by the relevant ethical review board (CPP-Ile de France IX, 18 January 2010). All data were collected anonymously. As this study includes data coming from regular care assessments, a non-opposition form was signed by all participants. An informed consent has been given by each patient. There was no ethical number according to the French law in 2012 (non-interventional study).

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographics, clinical characteristics, addictive behaviour and treatments are presented as measures of means and dispersion (s.d.) for continuous data and frequency distribution for categorical variables. The data were examined for normal distribution with the Shapiro–Wilk test and for homogeneity of variance with the Levene test. Comparisons between MDD and non-MDD, treated and non-treated MDD and remitted and non-remitted individuals regarding demographic and clinical characteristics were performed with the χ2 test for categorical variables. Continuous variables were analysed with Student t-tests for normally distributed data and in case of normality violation, additional Mann–Whitney tests were performed to confirm the result.

Variables with P values <0.20 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression model of factors associated with MDD and resistant MDD. The final models included odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. This study was a confirmatory analysis. No correction for multiple testing has therefore been carried out, which is consistent with recommendations.Reference Bender and Lange24 Analyses were conducted with SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). All statistical tests were two-tailed, with an α level set at 0.05.

Results

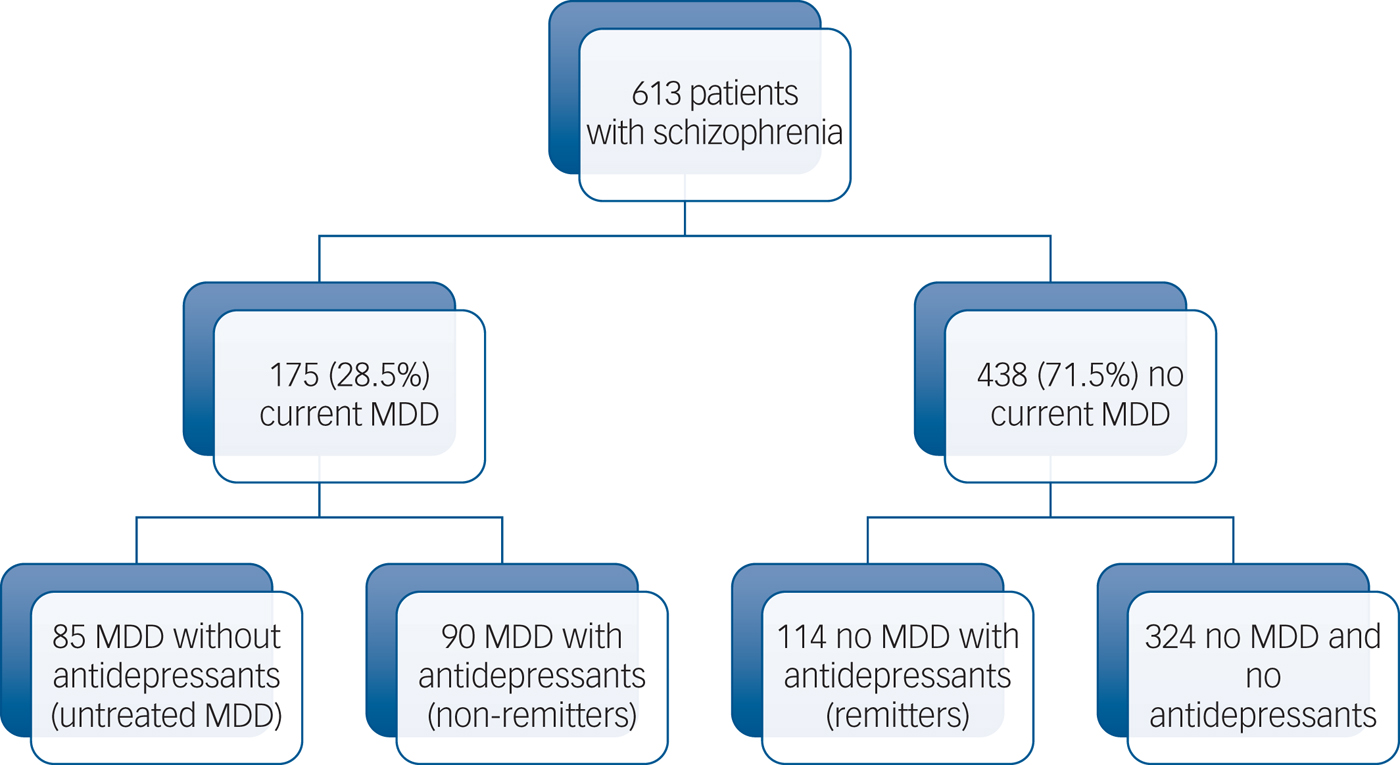

Overall, 613 stabilised community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia (mean age 32.3 ± 9.6 years; 73.9% men; mean illness duration 10.7 ± 8.1 years, mean PANSS score 67.4 ± 18.6, mean Birchwood score 8.7 ± 2.8) were included, and 175 (28.5%) were identified with current MDD (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). In multivariate analyses, MDD has been significantly associated with respectively paranoid delusion (odds ratio 1.8; P = 0.01), avolition (odds ratio 1.8; P = 0.02), blunted affect (odds ratio 1.7; P = 0.04) and benzodiazepine consumption (odds ratio 1.8; P = 0.02) independently of age, current alcohol misuse disorder, FGA administration and extrapyramidal symptom level (Table 1). Compared with remitted patients, non-remitted patients were found to have more paranoid delusion (odds ratio 2.3; P = 0.009) and more current alcohol misuse disorder (odds ratio 4.8; P = 0.04) independently of age, avolition, FGA administration and benzodiazepine consumption (Table 2). The antidepressant classes were distributed as follows: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (n = 127; 20.7%), norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (n = 53; 8.7%), tricyclics (n = 10; 1.6%), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (n = 1; 0.2%) and other antidepressants (including mianserine, mirtazapine, agomelatine and tianeptine) (n = 24; 3.9%). No antidepressant class and no specific antipsychotic were associated with higher or lower depressive symptoms level (all P > 0.05, data not shown). Including insight in the analyses did not change the response to antidepressant treatment.

Fig. 1 Study flowchart.

Table 1 Associations between major depression at baseline (defined by a Calgary score ≥ 6) and sociodemographic characteristics.

Clinical, addictive and treatment characteristics in a sample of 613 community-dwelling patients with stabilised schizophrenia. Univariate and multivariate analyses. Significant associations are in bold.

FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; MDD, major depressive disorder; SGA, second-generation antipsychotic.

a. As the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale is not suited to differentiate the different delusions and hallucination, delusions hallucinations and negative symptoms were evaluated by the Structured Clinical Interview for Mental Disorders v1.0, as well as current cannabis and alcohol misuse disorder.

Table 2 Comparison between resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and responders in a sample of stabilised community-dwelling out-patients with schizophrenia

Response was defined by a Calgary depression scale score <6 and current antidepressant treatment at the time of evaluation. Treatments were unchanged for at least 8 weeks at inclusion. As the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale is not suited to differentiate the different delusions and hallucinations, delusions hallucinations and negative symptoms were evaluated by the Structured Clinical Interview for Mental Disorders v1.0, as well as current cannabis and alcohol misuse disorder. Significant associations are in bold.

MDD was associated with MetS (31.4 v. 20.2%; P = 0.006) but not with increased CRP (P > 0.05). No association between non-remission under antidepressant and biological variables was found in the cohort.

Discussion

Our major findings may be summarised as follows: in a large sample of 613 non-selected community-dwelling out-patients with schizophrenia, MDD has been significantly associated with paranoid delusion, avolition, blunted affect and benzodiazepine consumption after adjustment for sociodemographic factors, other treatments and addictive behaviour. Antidepressants were found to be associated with lower depressive symptoms level; however, almost half of the patients were still classified with current MDD despite unmodified antidepressant treatment for at least 8 weeks. Compared with remitted patients, non-remitted patients were found to have significantly higher paranoid delusion and alcohol misuse disorder after adjustment for sociodemographic variables, treatments and addictive behaviour. MDD was associated with MetS but not with peripheral inflammation.

A total of 28% of our sample was identified with current MDD. This is consistent with most of the previous studies reporting MDD rates of around one-third of patients with stabilised schizophrenia (for review, see Buckley et al. Reference Buckley, Miller, Lehrer and Castle2). Overall, 44% of patients with MDD treated by antidepressants did not sufficiently respond to antidepressants and remained depressed.

MDD has been associated with avolition and blunted affect. Our study demonstrates the limitations of depression scales (CDRS and PANSS depressive factor) to discriminate depressive symptoms from primary and secondary depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. It may be hypothesised that this limitation may explain the high rate of non-remission under antidepressant in our sample. However, we found no association of unremitted MDD and negative symptoms. The CDRS was initially developed to determine depressive symptoms from schizophrenia-specific symptoms, but our results clearly suggest that this aim was not fully reached, given the strong association of CDRS scores with negative symptoms, especially blunted affect and PANSS negative and depressive subscores. Further studies should determine the best way to evaluate depression and antidepressant response in schizophrenia.

Paranoid delusions were associated with both MDD and non-remitted MDD in the present study, contrary to mystic delusion or hallucinations. In our sample, 63% of patients with MDD had current paranoid delusions at the time of the evaluation compared with 42.5% of those without MDD (P < 0.0001). Paranoid delusions and depression have both been associated with increased risk of suicide in schizophrenia.Reference Ventriglio, Gentile, Bonfitto, Stella, Mari and Steardo25 This association may be explained by the cognitive biases associated with both paranoid delusions and depression. In one previous study, participants with persecutory delusions were found to be less likely than both healthy participants and participants with depression to report criticising themselves for self-corrective reasons.Reference Hutton, Kelly, Lowens, Taylor and Tai26 Hateful self-attacking, reduced self-reassurance and reduced self-corrective self-criticism may be involved in the development or maintenance of persecutory delusions.Reference Hutton, Kelly, Lowens, Taylor and Tai26 Paranoia is driven by negative emotions and reductions of self-esteem, rather than serving an immediate defensive function against these emotions and low self-esteem.Reference Thewissen, Bentall, Oorschot, A Campo, van Lierop and van Os27 In a prospective study, depression was found in 30 out of 60 (50%) of the participants with schizophrenia and paranoid delusions, and predicted the maintenance of paranoid delusions over 6 months.Reference Vorontsova, Garety and Freeman3 Negative cognition has been found to be associated with the maintenance of paranoid delusions in two other studies.Reference Fowler, Hodgekins, Garety, Freeman, Kuipers and Dunn28, Reference Bentall, Rowse, Rouse, Kinderman, Blackwood and Howard29 Future studies of the FACE-SZ cohort follow-up should determine if MDD at baseline is predictive of paranoid delusions maintenance at 1-year follow-up. In cases of non-response to pharmacological treatment, some therapies have shown effectiveness in improving paranoia or MDD in patients with schizophrenia. Cognitive and behavioural therapy has shown effectiveness to reduce negative cognitions about the self, associated with paranoid delusions, and enhance self-confidence.Reference Freeman, Pugh, Dunn, Evans, Sheaves and Waite30 Preliminary data suggests that meta-cognitive therapy may be particularly useful in patients with schizophrenia with resistant MDD.Reference Hutton, Morrison, Wardle and Wells31

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that alcohol misuse disorder is associated with non-response to antidepressant treatment. This result is consistent with the findings of a recent meta-analysis suggesting that antidepressants may be moderately effective in patients with MDD and comorbid alcohol misuse disorder.Reference Foulds, Adamson, Boden, Williman and Mulder32 Another meta-analysis has suggested that alcohol abstinence was the best predictor of MDD remission in non-schizophrenic populations.Reference Lejoyeux and Lehert33 A recent 4-year follow-up study has shown that alcohol consumption is a risk factor for MDD onset in men.Reference Lee, Chung, Lee and Seo34 Depression has also been found to maintain alcohol consumption through shame.Reference Bilevicius, Single, Bristow, Foot, Ellery and Keough35 Alcohol misuse disorder may therefore be seen as a cause as well as a consequence of unremitted MDD. Current alcohol misuse disorder was identified in 5.9% of our sample, which is slightly lower than the mean of 9.4% found in a meta-analysis published in 2009.Reference Koskinen, Löhönen, Koponen, Isohanni and Miettunen36 This meta-analysis stipulated that there might be a descending trend in alcohol misuse disorder prevalence in patients with schizophrenia.Reference Koskinen, Löhönen, Koponen, Isohanni and Miettunen36 No previous data in the French schizophrenic population is available to date.

MDD was associated with MetS in the present study. This is consistent with the findings of three other studies carried out in different countries that found the same association.Reference Maslov, Marcinko, Milicevic, Babić, Dordević and Jakovljević37–Reference Suttajit and Pilakanta39 There is evidence supporting a pathological predisposition to MetS in both schizophrenia and MDD (for review see Kucerova et al. Reference Kucerova, Babinska, Horska and Kotolova40) and the association is currently considered as bidirectional. Altogether, the present findings combined with those of the literature suggest that MetS may play a potential role in the MDD onset and/or maintenance in patients with schizophrenia, this should be confirmed in future studies.

Antidepressants were associated with lower depressive symptoms level in the present study. Although the effectiveness of antidepressant cannot be directly concluded from the present cross-sectional results, these findings can be considered in favour of the effectiveness of antidepressants in patients with schizophrenia that has been suggested in two recent meta-analyses.Reference Gregory, Mallikarjun and Upthegrove9, Reference Helfer, Samara, Huhn, Klupp, Leucht and Zhu10 Consistent with the results of these meta-analyses, no antidepressant class was associated with higher or lower depressive symptoms in the present sample. Almost 40% of patients with MDD were treated with benzodiazepine. Benzodiazepine are usually used to treat anxiety and sleep disorders.Reference Birkenhäger, Moleman and Nolen41 The benefit of the long-term association of antidepressants and benzodiazepine has been highly debated, with some studies suggesting an adverse long-term effect of benzodiazepine consumption by counteracting antidepressant neurogenesis.Reference Boldrini, Butt, Santiago, Tamir, Dwork and Rosoklija42, Reference Wu and Castrén43 Benzodiazepine long-term administration may also have other side-effects in patients with schizophrenia, including impaired working memory and higher aggressiveness.Reference Fond, Berna, Boyer, Godin, Brunel and Andrianarisoa44, Reference Fond, Boyer, Favez, Brunel, Aouizerate and Berna45 Although buspirone, a 5HT1A agonist, has been suggested as a potential effective antidepressant augmentation strategy,Reference Sussman46 only two patients in our sample received buspirone (one with current MDD and one without).

We found no association between extrapyramidal symptoms and MDD or response to antidepressants, which is not in favour of the hypothesis of an iatrogenic effect of antipsychotic treatments. Contrary to the non-schizophrenic population, no gender effect was found in the present study, which suggests that MDD is not influenced by hormonal factors in patients with schizophrenia despite recent works on oestrogen influence in schizophrenia pathogenesis and maintenance.Reference Grigoriadis and Seeman47 We found no association between daily tobacco smoking and MDD in our sample, contrary to the non-schizophrenic population.Reference Tedeschi, Cummins, Anderson, Anthenelli, Zhuang and Zhu48 This may suggest a specific pattern of smoking behaviour related to specific N-Acetylcholine Receptor (NAchR) variants in patients with schizophrenia (for review see Parikh et al. Reference Parikh, Kutlu and Gould49). We found no association of MDD with peripheral inflammation. Inconsistent results on this point were found in previous studies carried out in similar samples with lower size.Reference Fond, Godin, Brunel, Aouizerate, Berna and Bulzacka12, Reference Faugere, Micoulaud-Franchi, Faget-Agius, Lançon, Cermolacce and Richieri13 Several factors may explain this discrepancy: the inclusion of stabilised versus acute-phase patients, the absence of consensual cut-off, the use of high-sensitivity CRP (and not interluekin-6) as a peripheral marker of inflammation, the different antidepressant class administration and the different risk factors for inflammation, including MetS, tobacco smoking, physical activity and diet.

Limits and perspectives

Our results should be taken with caution. As our study has a cross-sectional design, no causal link can be definitely inferred. The number of previous antidepressant treatments was not reported. Other prognosis factors including age at first depressive episode, age at first antidepressant treatment/duration of untreated depression, number of lifetime depressive episodes and lifetime duration of depression should also be included in future studies. Long depressive illness duration and the number of depressive episodes may affect the response to antidepressants. Our sample may not be representative of all patients with schizophrenia, particularly because institutionalised, admitted to hospital or very disabled patients (making thorough assessment difficult) were not referred to the Expert Centers. Sleep disorders, physical activity and vitamin D blood levels may help to explain the resistance to antidepressant treatments, as well as daily dietary intake and microbiota disturbances, and should be explored in further studies. Add-on complementary agents, including omega 3, vitamin D, zinc, S-adenosyl methionine, N-acetyl cysteine and methylfolate, may also be useful in the treatment of MDD in schizophrenia and should be further explored.Reference Schefft, Kilarski, Bschor and Köhler50–Reference Firth, Carney, Stubbs, Teasdale, Vancampfort and Ward52

Strengths

To the best of our knowledge, the present sample was the largest of all studies exploring MDD in community-dwelling patients with stabilised schizophrenia. This sample size allows the exploration of the factors associated with resistant MDD, which has been done for the first time in an ecological community-dwelling sample of out-patients with stabilised schizophrenia. The use of homogenous and exhaustive standardised diagnostic protocols across the Expert Centers and inclusion of a large number of potential confounding factors in the multivariate analysis (sociodemographic variables, psychotic symptoms, addictive behaviours and detailed treatments) may be considered as strengths of this work. The use of a specific depression scale is also another strength, as well as the exploration of specific symptoms rather than global positive/negative symptoms scores. The national multicentric sample of patients with schizophrenia referred to the Expert Centers may be underscored as another strength.

In summary, combined with the literature, our findings suggest that MDD is frequent in community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia. Antidepressants are associated with lower depressive symptoms level, however a high proportion of patients remain depressed despite treatment. Paranoid delusion and alcohol misuse disorder should be specifically explored in non-remitted patients with schizophrenia with comorbid MDD. These findings should be confirmed in interventional studies.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.87.

Funding

This work was funded by Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, Fondation FondaMental (RTRS Réseau Thématique de Recherche et de Soins Santé Mentale), by the Investissements d'Avenir programme managed by the ANR Agence Nationale de la Recherche (reference no. ANR-11-IDEX-0004-02 and ANR-10-COHO-10-01) and by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale.

Acknowledgements

We thank the nurses and the patients who were included in the study. We thank Hakim Laouamri and his team (Stéphane Beaufort, Seif Ben Salem, Karmène Souyris, Victor Barteau and Mohamed Laaidi) for the development of the FACE-SZ computer interface, data management, quality control and regulatory aspects. We also thank George Anderson for editorial assistance.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.