On a fundamental level, war is about power. Battlefield victors impose their will over the enemy, while states reap the rewards of hardy soldiers fighting successfully on their behalf. Men’s adventure magazines relied on this narrative construction wherein both individual combatants and the country as a whole profited from the experience of war. War made men, while also making America a more powerful, if not indispensable, nation.

In a similar arc, the macho pulps crafted a discourse in which gender and sexuality also hinged on power relations. Readers’ knowledge of “normal” sexual relations rested, in part, on how the pulps reinforced prevailing social relations while simultaneously offering images and storylines that editors deemed most desirable to their core audience, of which the working-class market occupied a significant portion. As with narratives on war, adventure magazines depended upon a set of simplified dualisms: good versus evil, masculine versus feminine, primitive versus civilized, and white versus dark. Such storylines might then fuel men to perform in ways they reasoned were socially acceptable. Thus, as Judith Butler has argued, we might consider discourse not only by its intellectual origins but also as a “condition and occasion for further action.”1

The discourse of gender and sexuality in the macho pulps clearly placed men in a dominant role. If overbearing women at home were aiming to reign supreme over the domestic sphere, men could retaliate by objectifying the very thing they feared. Exotic locales proved particularly inviting for pulp writers who responded to these social anxieties. Whether on a Polynesian island or in the enticing “Orient,” adventurers could wield their power over the allegedly untamed and sexually liberated native. Boys transformed into men not only by physically conquering these natives, but by exhibiting their sexual power over “savage” beauties. In the process, the man-making experience of both war and sexual conquest might seem more meaningful to young readers aspiring to break free from the seemingly oppressive atmosphere of Cold War culture.2

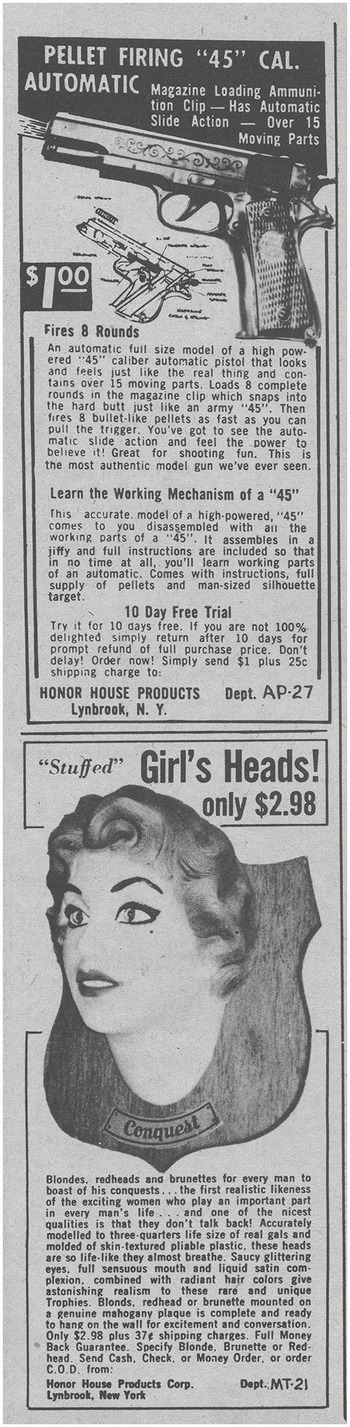

Typical of mid-century sexism, the pulps’ construction of gender reinforced images and practices whereby men controlled women. Adventure magazines surely were not alone in their paradoxical storylines both praising and condemning women for taking charge at home in the 1950s. Yet the macho pulps assertively led their readers across the boundaries of outright misogyny. The July 1959 edition of Battle Cry, for example, included an advert hawking “‘Stuffed’ Girl’s Heads.” For only $2.98, men could purchase a woman’s plastic head – with “saucy glittering eyes, full sensuous mouth and liquid satin complexion” – mounted on a genuine mahogany plaque. Here was a “unique trophy” that offered the chance for “every man to boast of his conquests.” While the ad drew attention to the heads’ life-like appearance, it also bragged that “one of the nicest qualities is that they don’t talk back.”3

Sexist representations of women as objects filled the pages of adventure magazines. Stag noted how the Russians had given up the idea of female astronauts since their first space woman “broke down in hysterics” during a secret flight. Male featured a photograph of a topless dancer performing at the annual meeting of the National Wholesale Furniture Salesmen. Finally, Man’s Illustrated included an article titled “Women – Which Nationality Is Best?” This “guide to the world’s greatest mistresses” opened with its author grumbling that American men were suffering in a “matriarchal society,” barely surviving against a “gigantic conspiracy to keep our women dominant.” Luckily, foreign women all had the same ambition – to snag a Yank husband. The article then took its reader on a world tour comparing “Malayan beauties” with Asian “bombshells” and “abnormally oversexed” Polynesians. Incredulously, the piece also offered insights into the “secret-flesh markets” of Singapore and Macao where “even the slave girls prefer American owners.” If conflict and struggle informed men’s understanding of domestic gender relations, at least overseas they could exhibit power in unabashed fashion, if the pulps could be trusted.4

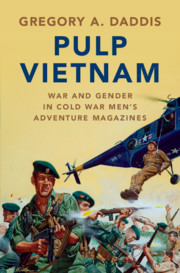

Fig. 3.1 Battle Cry, July 1959

The imagined foreigner thus became a mainstay in men’s adventure magazines. The pulps’ multiple constructions of women, however, surely left some readers dubious of their own prospects. While depicting women as dangerous, authors and illustrators demonstrated that, in the right locales abroad, they were also sexually available. Magazine articles spanned the globe exposing the best “sin-filled” places where women supposedly threw themselves at American men. In the “sensual city” of Rome, readers could delight in the ease of organizing an orgy given so many “wild playdolls.” In the “swinging land” of Sweden, US visitors could savor the “lovely lasses” who were “as broad minded and uninhibited as every man wants them to be.” Unsurprisingly, Rio – “Sexville of the Americas” – proved a popular destination for “fun-hungry guys on the loose.”5 The challenge, though, was how to differentiate between the good and the bad. Were women devious vamps or sensual playthings? Should men hate women or desire them? Perhaps the safest bet was to do both.

Throughout the years leading to America’s involvement in Vietnam, adventure magazines reinforced mythical notions of “racialized sexuality.” White foreign women, mainly communist or Nazi femmes fatales, might be packaged as passionate seductresses, alluringly dangerous (yet typically surmountable) to the heroic male protagonist. But the pulps seemed to take special pleasure in fetishizing the more mysterious, perhaps more desirous, darker “Oriental” woman. In Edward Said’s estimation, Western conceptions of the Orient long have suggested not only “sexual promise (and threat)” and an “untiring sensuality,” but also “unlimited desire” and “deep generative energies.” This sense of “unbounded sexuality” pervaded adventure magazines. In short, women of other races invited sexual conquest.6

For younger working-class readers, many of whom likely had yet to travel overseas, the idea of beautifully exotic and sexually subservient women must have held great appeal. Pulp heroes engaged in sex without emotion or consequence. In the process, they could reinforce unequal power relationships that seemed so fragile to men in the 1950s and early 1960s. The pulps’ message about gender and sex, however, held ominous implications. Fears of sexually enticing women, the desire to control them, and the failure to do so seemed only to inspire more fear. Such narratives ultimately would send a powerful message to young American boys, one that seemingly endorsed soldiers’ sexual violence against native women in far-off places like South Vietnam.7

The Red Seductress

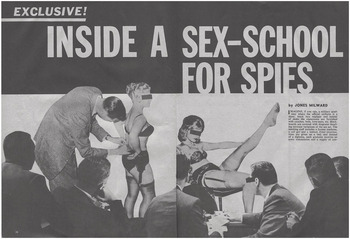

Stories on alluring yet treacherous female spies were a Cold War mainstay in adventure mags. In “Sex Is Their Secret Weapon,” Battle Cry highlighted how an “unusual number of prostitutes” were communist agents or associating with known communists. The magazine discerned a clear pattern, surely directed by the Kremlin. “Using sex, along with other weapons of the cold war, the Reds are actually committing themselves to warfare.” Such a metaphor proved immensely popular in the early 1960s. The communists were using “sex as a weapon in espionage,” and, according to Man’s Illustrated, “sexological warfare, as practiced by the Russians, has been alarmingly successful against the West.” Worse, these tactics seemed to pose an existential threat to the United States. “Sex harnessed to politics, either local or global, can be a force as destructive as a nuclear bomb.”8

With every page turned by pulp readers, ex-Nazi or communist man-eaters waited to pounce on American men and turn the tide of the Cold War. Russia apparently maintained a spy fleet of “lush honey-blondes from the Ukraine” and “satin-bodied Oriental girls from Azerbaijan” who traveled on luxury liners in hopes of blackmailing Western travelers and gaining vital intelligence for Moscow. All-action book bonuses featured German Fräuleins selling information to the Reds from within the CIA’s West Berlin office.9 An article by Mario Puzo even showcased how the allies could use sex as a weapon, highlighting “four Free World spy dolls whose lush, exciting bodies had ferreted out dozens of Russian top secrets.” Of course, these women could not be trusted, evidenced by one “Judas joy girl” who had “traitorously sold out to the Reds.” The hero’s assignment? “Bed-hop from one wanton to another” until he uncovered the turncoat and brought her to justice.10

The frequency of pulp storylines in which women used their bodies to deceive suggests these femmes fatales were symbolic of larger male anxieties during the Cold War. Women might offer love, but also deception and humiliation. Certainly, some young readers must have judged sex as both alluring and precarious. In this regard, prostitutes served as a vivid demonstration of male fears. Stag illustratively noted how pretty European communists filtered through Castro’s Cuba before arriving in America as part of a massive “sex-spying” ring. Targeting defense officials and US servicemen, these “prostitute-spies” then filtered their secrets back to Russia and China. Moreover, such duplicity threatened the burgeoning American effort in South Vietnam. One popular account revealed how the Vietcong were employing, “with considerable success, young beauties who pose as bar-girls and prostitutes and worm military information out of relaxed and trusting Americans they dance, drink, and sleep with.”11 The message for pulp readers seemed obvious: women could not be trusted.

This woman-as-seductress image resonated with pulp readers at the same time Americans in the 1950s and early 1960s were coming to grips with an increasing openness on individual sexuality and a surge in academic sexual studies. If some women seemed to be rejecting their femininity and traditional role as child-rearing caregivers, critics more easily could argue that they posed a danger to predominant social, economic, and political conditions. Additionally, these shifts in sexual attitudes occurred when Cold War fears of communism echoed throughout American society. It was only a small step for detractors to link sexually liberated women to communist subversives. Both, in their own way, threatened the male-dominated status quo.12

Adventure magazines made sure their readers understood that deceitful women were not simply a sexualized byproduct of the Cold War. Vamps also had used their bodies to lure good men astray during World War II. Propagandist Tokyo Rose may have captured America’s attention in the 1940s, but the pulps left little question that seductresses were operating in boudoirs across the globe during the war. Brigade’s “The Passionate Widow Who Seduced a B-17 Pilot” presented a brave American flyer stationed in London. In between bombing runs over Germany, he meets Celeste, “a woman who could blot out with the ravishing flesh of her body all thoughts, all remembrances of war’s mayhem and madness.” Though Pete professes his love for her, by story’s end we find that Celeste had been married to a Luftwaffe pilot killed in the blitz over London. To avenge his death, she leaves her children behind in Germany to become an undercover agent and report on British and American air movements. As Pete’s commander tells the heartbroken airman, “You were her pigeon. And don’t feel badly, you weren’t the first.”13

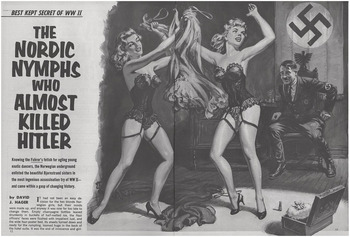

While beautiful Hungarians and Poles engaged in “bedroom espionage” against American servicemen and their allies, even the Nazis were not safe from scheming women who hoped to change the course of history thanks to their sexual intrigue. In one story from Fury, Ilse Stöbe, who supposedly looked like a “blonde houri from a sultan’s harem,” bedded SS General Reinhard Heydrich in an attempt to keep the allies informed of German war plans. Her dual role as agent and mistress, however, suggested that female combatants could not occupy the same space as the traditional male soldier.14 While men could claim honor and respect for their battlefield sacrifices, women with similar aspirations to fight against evil still had to be villainized in order to maintain a gender-acceptable wartime narrative. Thus, in the “The Nordic Nymphs Who Almost Killed Hitler,” the female protagonists who sleep with the local Gestapo and important Nazi visitors from Berlin appear more tawdry than heroic.15

Everywhere, it seemed, women were luring men to their doom. On the home front, wives were entrapping men in a “cage of domesticity,” while on the extended battlefield, temptresses played the role of pulp villain far more than they did of victim. “Kill-crazy pirate girls” prowled the coastlines of Red China in “murderous female hyena packs.” Nympho spies helped lead the Japanese to defeat in World War II. Meanwhile, outcast “brothel pigeons” roamed Shanghai’s Tibet Road. Betrayal looked as if it was an integral part of the female constitution.16

Lest readers question such gender discourses, respected scholars seemed like they might be confirming pulp narratives of women using their supposed innocence to trap and betray. In one of the most popular works on the French-Indochina War, Street without Joy, famed war correspondent and Howard University professor Bernard Fall maintained that no less than one-third of all French posts fell during the war thanks to the efforts of Viet Minh saboteurs, many of whom were women. For Fall, it remained a “matter of conjecture whether the element of ‘vice’ which [women] added to the war was not outweighed by the element of femininity.”17 It should not surprise that American successors to the French armed forces cast wary eyes on alluring yet equally frightening Vietnamese women.

These depictions could be unnerving not just for soldiers deploying overseas, but also for young men inexperienced in sex. Surely many must have wondered if sexual pleasures were worth the risks as they fretted over their own virginity. Comics instructed them to “never turn your back on the female of the species.” World War II propaganda posters displayed “loose,” impure women as the primary vessels of sexually transmitted diseases. And pulps like For Men Only ran articles on French prostitutes who murdered their male clients.18 Sexual threats piled ever higher in the postwar era, to terrifying heights. Writing in the late 1940s, Simone de Beauvoir saw a natural consequence of this imagined peril, of men “suffering from an inferiority complex.” To the French existentialist, “no one is more arrogant toward women, more aggressive and more disdainful, than a man anxious about his own virility.”19

In many ways, adventure magazines took advantage of prevailing anxieties and sexist attitudes rooted in deep fears of women and their supposed power to abuse sex. One Stag essay demonstrated the extreme. In a case that grabbed national attention, Newark resident Monique von Cleef was arrested for running a “torture-for-thrills” house in her twenty-room mansion. Stag disapprovingly noted how this “domineering blonde” and “priestess of a strange cult of the ‘sick’” doled out “every form of degradation to her select, offbeat clientele.” Fortuitously, a New Jersey detective willingly laid his body on the line to “invade her temple” and bring the “leather-suited, booted blonde” to justice. While the courts wrestled with the issue of policing private sexual conduct, men’s magazines took a different approach when it came to sadomasochism. For Stag, the issue was not about getting pleasure from inflicting or receiving pain. That existed, to some extent the pulp argued, in “ordinary” relationships. Rather, Mistress Monique problematically wanted to dominate men instead of submitting to them. As Stag hissed, “Men make themselves her victims because they are so sick they must be turned into slaves.”20

Von Cleef’s transgression, of subverting traditional gender norms, easily fed into established Cold War anxieties over morality, sexuality, and masculinity. All these fears were exacerbated when interlaced with the combined threats of international and domestic communism. When Male published a “true” book-length adventure story on a US agent fighting against a “super-secret Red subversion corps,” the magazine ensured that “full-bodied” blondes played an integral part of the story. As in so many other plot devices, violence and sexuality went hand-in-hand.21

That communist subversives so effortlessly could use sex as a weapon meant few men were safe, being instead imperiled by women who were inhabiting bodies that were weapons, a point clearly embraced by men’s adventure magazines. Spy-nymphs were dangerous because of their “cunning brains” and “luscious bodies.” In one story, a French agent’s beauty put her in “complete control” of an Austrian target, the corpulent businessman unable to resist and falling to his knees before her.22 Worse, it seemed, these seducers were pursuing American soldiers using “sex, Marx and blackmail to ‘persuade’ GIs to turn traitor.” Stag left little doubt who held the advantage in these exchanges. In a story on an Amsterdam “seduction ring,” the stunning temptress effortlessly beguiles American GIs who are just “kids.” “Brash, arrogant on the outside; underneath scared, lonely, and oh so trusting.”23 Likely, many young men deploying to Vietnam in the 1960s fit this description, further laying the groundwork for an adversarial relationship with the Vietnamese population in a frighteningly confusing wartime environment.

At its core, however, the ideological conflict of the Cold War wasn’t necessary to show the dangers women posed. Women were seductresses not because they were communists, but because they were women. In one shocking example, the March 1966 issue of Man’s Illustrated ran a story on “lustful gals” who willingly provoked “sex attacks.” The piece argued that far too many rape investigations ignored the “crime-provocative function of the victim” and that evidence clearly showed an “unconscious desire on the part of the victim to be attacked.” Since any healthy woman could successfully keep a man from forcing himself on her, the article intimated that in many cases “the female ‘victim’ was merely engaging in the time-honored game of putting up mock resistance to an act she truly wanted.” How many young readers left such stories with a lack of empathy for survivors of sexual violence? How many may not have thought twice about the “mutually enjoyable” act of raping a South Vietnamese woman?24

It was no coincidence the same issue showcased the US Army’s 173rd Airborne Brigade fighting heroically against the Vietcong in South Vietnam. With choppers whirring overhead and bullets slamming into the ground among a group of GIs, a veteran soldier turns to his young captain experiencing his first taste of combat. “We’re no longer virgins,” he grins.25

The Exotic “Oriental”

The same year that Man’s Illustrated defended men against sexual “frame-ups,” Leland Gardner’s exposé Vietnam Underside offered a slightly different view of the female seductress by recounting the sexual history of Southeast Asia. To Gardner, it was the heritage of the exotic and erotic Asian to “wallow in the sensual.” These women were not inherently immoral, though buyers of the roughly 25,000 professional prostitutes in Saigon surely beware. Rather, such a high number of sex workers apparently resulted from the presence of virile American men, a refreshing contrast to the “completely inadequate” South Vietnamese male who was unable to satisfy his sexually “insatiable” female partner. In paternalistic fashion, Gardner recounted how the “Viets laugh a lot, but they also throw tantrums and go into vicious, violent rages on an individual basis. Much of their humor is childish because, as a people, they have not yet become sufficiently aware to be concerned about politics, national economy or sociological problems.”26

This construction of Asian as child had long historical roots. Westerners sought to demonstrate their cultural superiority by comparing themselves favorably to the inferior other, all the while attaining a rationale for imperialist expansion overseas. In the aftermath of World War II, if not before, Americans particularly welcomed such notions. After having fought a brutal race war in the Pacific against a determined and “savage” enemy, depicting Japanese as “small, childlike, and feminized” allowed American occupiers, according to historian John Dower, the opportunity to transform their erstwhile foes “into a compliant feminine body on which the white victors could impose their will.” With the proper rearing, these new fathers could guide their Asian wards into a more modern community of nations overseen by a benevolently patriarchal United States.27

In keeping with this narrative – of devaluing women in terms of both gender and race – the submissive, feminized child conveniently blossomed into a servile beauty eager to please her Western master. Amy Sueyoshi argues that these depictions of submissive Asian women proliferated in the early 1900s, “just as increasingly independent white women appeared to be undercutting marital stability.”28 The Japanese geisha, in particular, epitomized popular images of obedient, self-sacrificing Asian servants who promised a sexual alternative to modern feminist agitators back home. Instead of war-mongering savages, Asians usefully could be reconceived as feminized, “unthreatening objects for collection and consumption.”29

American soldiers serving overseas reveled in these portrayals, applying them to their own wartime sexual experiences. In World War II, GIs stationed on Luzon encountered young Filipinas offering sex, one medic recalling that he had “never had a girl and didn’t want to die without knowing.” On Hotel Street in Hawaii, William Manchester found “more massage parlors, strip joints, and pornographic shops than cafés.”30 After the war, roughly 1,100 Japanese women reported sexual attacks by American occupiers, some of these assaults conceivably a result of GIs who viewed the locals as ripe for sexual conquest, if not retribution after a long, hard-fought war. The trend continued into Korea and Vietnam. Veterans spoke of the pleasures offered in Bangkok and Hong Kong, one serviceman labeling the Thai capital a “fucking colony.” To many Americans, Asia seemed the “brothel of the world,” a place where prostitutes offered what men ostensibly desired most – “sex in its primitive sense, untrammeled and undiluted by feelings of guilt, fear, sentimental love, respect, and competition.”31

The macho pulps conformed to these impressions by promulgating the exotic Oriental narrative. In 1953, Man’s Day showcased an Asian fishing village, a “male paradise” in which female divers, all clad in bikinis, collected seaweed while the men were “content to supervise and be happy henpecked husbands.” Adventure featured a story on New Caledonia, “The Island of Lonely Girls,” where local entrepreneurs had “no trouble in recruiting exotic beauties” as “girls by the score applied for work” because they “were imbued with a patriotic desire to make the stay of the brave Americans … as pleasant as possible.” Stag’s confidential section even shared how bra manufacturers had rated Polynesian women “as having the world’s most beautifully shaped breasts.”32

These exotic locales, though, paled in comparison with what Japan supposedly offered virile American men. Because pleasure was “Japan’s best-selling commodity,” Battle Cry judged it the place where the US Army learned about sex. One pulp maintained there was “no topping the Japanese prostitute … because she was sincerely able to fall in love with every man she met.”33 Man’s Illustrated went further, claiming that a Japanese woman was able to “sense the moods and feelings of her male guest like a mindreader.” The comparison with domineering American housewives could not have been clearer. “Were Japanese women really different?,” the magazine asked. “Damned right they are,” the author replied. “Her pleasure comes from catering to the wants and whims of her man, and she does it like nobody else in the world.”34

For those readers who truly believed they were being emasculated at home, such storylines must have struck a deep chord. Unlike “aggressive” American women who were contesting Cold War gender roles, the purportedly subservient Japanese held tremendous appeal. So much so that one company in Newport Beach, California actually marketed itself to lonesome men on the basis of the exotic Oriental fantasy. “For centuries,” its ad claimed, “Japanese girls have been trained since childhood in the art of pleasing men and catering to their every wish and desire.” For only one dollar, membership in Japan International included “hundreds of Japanese girls … of all ages.” This commodification of Asian women might be viewed as a response to the depiction of the female body as weapon. Submissive women were less threatening, perhaps less duplicitous. Of course, on the battlefields of South Vietnam, one could never be sure. At least on R&R in Japan or Bangkok, storylines boasted, American soldiers could revel in the best Asia had to offer.35

To be sure, the imaginary exotic Orient proved a popular entry not only in the macho pulps, but in Cold War movies as well. Films reinforced the idea that Asian women were merely sexual playthings for American adventurers overseas. The opening scene in John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962), for example, depicts American GIs drinking and carousing in a Korean bar during the war. Pin-up girl photographs are tacked to the wall, perhaps as a reminder that the bar’s inhabitants are temporary wartime substitutes for hometown gals left behind. It is clear the local women, many of whom are shirtless in their brassieres, are there only to please their clientele and earn some easy cash, one placing money in her dress as the camera pans across the smoky bar. For a brief moment, a lanky American soldier enters the scene wearing only boxer shorts and combat boots. The fighting in Korea might be grueling, but the movie implied that respites with local bar girls offered pleasures few men back home could enjoy.36

Looking back, the irony of the bar scene now seems palpable. GIs covered the walls with desirous white pin-up girls yet deemed the erotic Asian as offering unique sexual gratification against which American women could not compete. Women at home were difficult and smothering. Women in foreign lands were deferential and gratifying. With such sexist attitudes prevalent across Cold War popular culture, no wonder men’s magazines presented storylines accentuating women of “dark” or “dusky” races.37 The pulps clearly fetishized over the topless Polynesian woman or the polygamous Ottoman lying about in an exotic harem. However, this “supposed sexual licentiousness” of the uncivilized foreigner did not extend to African Americans back home. While the “oversexed-black-Jezebel” loomed large in both American mindsets and discriminatory practices, especially in the antebellum era, the macho pulps excluded African American women from any discussion on sexual fantasies. Openly admitting to a relationship with a black woman likely would have been taboo, if not abhorrent, to most white, working-class readers of the pulp genre.38

Rather, adventure magazines took readers overseas to fulfill their racialized, exotic fantasies. In “The Nude in the Blue Lagoon,” Valor rhapsodized over a Samoan girl representative of “the exotic Polynesians who believed in nature; and nature meant complete freedom in matters of sex; that is until they married.” Luckily for the story’s hero – whom Mauie calls “Mr. America” – the eighteen-year-old has not yet wed, her “tight, well-formed breasts … tanned by daily exposure.” His “savagely” pounding heart alludes to the fact that pulp champions could expend their beastly side without damaging the more wholesome white pin-up girl next door. Of course, Mauie needs rescuing by the American after she is attacked by a giant sea turtle while swimming in the lagoon, rewarding her savior with kisses after the harrowing experience. Yet the appeal of these tribal women came from more than just sexual promise. In the same issue of Valor, an American explorer travels to the “forbidden” heart of Africa and encounters a tribe that lives in “a man’s world.” The autobiographical account noted how the social hierarchy was based on both age and sexual discrimination and that “marriage means complete subjugation for the Xosa women.”39

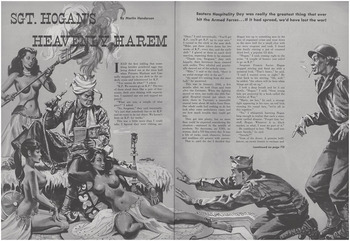

Regardless of the woman in question being black or white, the pulps made clear that nowhere in American suburbs or working-class neighborhoods could men enjoy the “eastern hospitality” offered in far-flung lands. And nowhere did that hospitality loom larger than in Oriental harems. Adventure magazines relished in imagining what harems might look like, their artists painting bare-breasted concubines alongside exotic accoutrements, hookah pipes, and peacock feathers. Sensation featured a World War II army sergeant in Oran, North Africa taking advantage of the supply system to tender “three slave girls” the proper “inducements” so he could enjoy their company. Another offering in Stag focused on a similar tale, the North African campaign an apparent cultural crossroads where white men gained sexual access to the local population. Societal and geographic accuracy, though, did not preclude writers from locating harems in faraway places like India, where “temple women” guaranteed “to turn the most fumbling, inept man into the world’s finest lover.” Apparently sexual gratification could be found almost anywhere in the imagined Orient.40

It would be wrong, however, to dismiss the imaginary East as exclusively pleasurable. For every representation of the docile and reverential geisha, there were equal stereotypes of the wily and calculating “dragon lady” who lacked any empathy or emotion. Like the red seductress, Asian women, in particular, seemed just as deceitful and capable of using their bodies as weapons of war. Stag opined how “Asia’s comfort houses” had used “nymph decoys” to bait and lure in unsuspecting men during the Chinese Civil War. Male featured a story on a “half-trustworthy Kowloon ‘Passion Kitten’” who aided American agents in seducing a Chinese intelligence chief to defect to the West. The Hong Kong woman is an expensive call girl, her main role to have sex with the potential turncoat and hand him over to the CIA. No wonder American GIs, typically conflating all Asian races, recalled how their orientation to Vietnam included stark warnings of “gook whores and Vietnamese women in general.”41

Whether Japanese, Samoan, or Vietnamese, none of these women had much opportunity to speak for themselves in the macho pulps. Often, they were little more than props in the storyline. A sensual vamp, luring men with sex. An unnamed girl, raped in her village. A voluptuous pin-up, strategically placed between war stories.42 While pulp writers made the decision to silence female voices, they hardly were exceptional in their choices. Edward Said found that in western models of the Oriental woman, “she never spoke of herself, she never represented her emotions, presence, or history.” Instead, it was the male author who “spoke for and represented her.” In the process, these women seemed to lose a bit of their humanity. Neither ideology nor race seemed to matter all that much. Women were the “other,” plain and simple.43

This type of objectification thrived in both pulp advertisements and storylines. One 1975 study analyzed the ways in which magazines commonly depicted women, from “dependent on man” to “overachieving housewife.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, the researchers found that “woman as sexual object … appeared more frequently than any other category in both men’s and general magazines.” Pulp ads reinforced this conclusion. Men could purchase “Harem Jamas” for their significant others, a “nite time garment inspired by the fashions of the near East, where often hundreds of women compete to attract one man.” Alternatively, they could peruse fashions from “Nightie Nights on the Nile” and order a sheer “Egyptian Slave Girl” lounging robe.44

Adventure stories must have tempted readers to consider purchasing these outfits, in hopes they might role play and realize their fantasies at home. Man’s Conquest, for example, included a piece titled “Buy a Slave Girl!” In the story, a World War II veteran working in Cairo poses as a wealthy businessman to write a story on the Arab “flesh markets.” For only $160 he purchases a nineteen-year-old Jordanian, a beautiful “nice kid,” freeing her not long after getting the bill of sale and key to her chains.45 In All Man, an American is forced to help run a female slave trade across the Arabian Peninsula, shuttling “livestock” of Bedouin women of ages ranging from twenty-five to fourteen. Finally, in “The Love Slave of Hadramut,” an American oil engineer buys a “sweet and gentle Arab girl” for $64. Since he is superior to the local men, he considers himself an “ideal master” and appears content with his acquisition. “Mimsha was docile and delightful. She made no trouble at all. At my beck and call, she was soothing, exciting and wicked, a veritable personification of a Houri maiden.” The eroticization of power relations could not be more obvious.46

It mattered, of course, that the oil engineer was white. In the pulps, if not broader Cold War culture, American masculinity rested on notions of racial superiority. White men were no match for the savage other in the pages of these magazines. In the imagined Orient, adventurers could revel in sexual decadence, yet still maintain their civility and thus dominance over the local population. Women in “primitive tribes” appeared forever sexually available. Pulps like Stag persistently represented female natives as having soft black hair, tanned skin, firm breasts, and “many lovers before mating.” All of them seemed to admire Americans. The illusion undoubtedly attracted young male readers whose definitions of masculinity were being progressively shaped by notions of physical prowess, racial authority, and sexual assertiveness. And what better place to satisfy male impulses than in the arena of war?47

Gendered Fantasies

If the pulps are to be believed, air and sea travel must have been a precarious business in the middle of the twentieth century. Stories of downed pilots or sailors lost at sea inundated the adventure mags. Not surprisingly, these faulty modes of transportation functioned as convenient plot devices in which the hero washes ashore or lands on an island inhabited by sexually attractive and available local women. Beyond the frontiers of civilization, the unshaven and usually bare-chested protagonist quickly establishes his authority over the male tribal leaders, an unintentional colonialist effortlessly mastering his new domain. Exotic tales like these evoked images of John Smith and Pocahontas, with the latter cheerfully giving herself to an outside explorer representing an ordered Eurocentric society at odds with native savagery and sexuality. In these narrative constructions, the white male stands tall in a land of puerile indigenous people.48

The South Seas proved a popular locale for castaway stories. One merchant mariner hit a storm between the Philippines and Guam and went on to “live a native’s life for six years” after washing ashore on a tiny tropical island. There he found “scantily clad women,” marrying one according to local traditions that allowed him to star in his own pornographic feature – it was “custom for the populace to watch the consummation of a marriage.” Another Male adventurer, stranded on the island of Borneo, apparently lucked into a setting with attractive locals. “Now they always tell you native women are beautiful,” he declared; “they’re not – I’ve seen plenty and most of them are dogs.” In Borneo, though, he meets plenty of young women, all whom have a “nice figure and a pretty face. When they get old, they get ugly, and they get old fast – 35 or so.” Once more fortunate, the hero attracts the young Lini, who fits perfectly the mold of obedient and sensual Oriental lover, her breasts like “two giant scoops of coffee ice cream.”49

Such lustful imaginings allowed pulp writers the chance to combine fantasies that knew no geographic boundaries. Thus, shipwrecked sailors could land on Japanese islands of “castaway geishas” or touch down on the Malabar coast in southern India and indulge in “delightful beauties,” any of whom “would have been enough to knock the breath out of a man.”50 Action for Men featured the tale of an American washed ashore on an atoll in the Melanesian archipelagos in 1934. For ten years he lived happily on a lost southwest Pacific “harem island,” the tribal chief offering him a wife of his choice not long after arriving. Only in 1943, nearly a full decade later, did the American learn of World War II, ultimately fending off Japanese invaders with only spears and an “ancient first World War pistol.” Even on the very outskirts of western civilization, men could fulfill their dual roles as sexual conqueror and heroic warrior.51

This conquest of savage lands reinforced the macho pulps’ predilection for aggrandizing the hardy frontiersman at the center of heroic wartime stories. Had not World War I sharpshooter Alvin York flourished in battle because of his ability to pull from a mythic frontier past? Survival along these spaces where the “civilized” encountered the “savage” had long required martial skill, but adventure mags emphasized how military and sexual conquest seemingly went hand-in-hand. There, the sexual subjugation of local women took center stage as American (and occasionally British) heroes battled against a non-white, savage enemy.52

In the January 1961 issue of Stag, for instance, the protagonist, aptly named Hunter, skirmishes with Japanese patrols on Borneo, his World War II mission to “stab ice cold fear into the hearts of the Japs.” During the fighting, he enlists three beautiful local girls, author Bill Wharton taking an almost obligatory pause to describe their “small, firm breasts and lithe, firm limbs.” After training a “force of guerrilla head-hunters” who mercilessly defeat the Japanese, our hero decides to remain on the island and tutor additional local warriors to combat the communists in Malaya. With his three wives, he fathers eight children. There is no question Hunter is a virile warrior. By story’s end, the “great man” miraculously retains his civility despite engaging in this skulking way of war and living in a hut strung with Japanese skulls.53

While these stories promoted a form of sexual conquest that had reinforced earlier European imperial projects, they also revealed that white men still could demonstrate their superiority over uncivilized, darker-skinned men. The supposedly hypersexual nature of African Americans certainly stood apart. Whites long had worried over blacks’ “aggressive sexuality,” thought to be an “anatomical peculiarity of the Negro male.”54 In pulp world, however, men in alien cultures appeared far less intimidating. Adventure mags fortified cultural stereotypes where insipid brown men from the Pacific, the Middle East, or Southeast Asia were deemed conniving, immoral, and decidedly feminine. The ease with which a downed pilot rated the finest-looking native on the island said as much about the native man as it did about the castaway hero. In many ways, the magazines’ stories illustrated how depictions of colonization endured even as the actual colonies of Europe were collapsing under the weight of post-World War II nationalistic fervor.55

It was important that these gendered fantasies occurred overseas where there was no fear of interracial coupling or a mixing of races that might pose a menace to American social norms. During World War II, the US government viewed interracial marriages as an unwelcome and “unintended consequence” of the global conflict. While some magazines like Ebony and U.S. Lady published a few positive stories of US servicemen marrying European or Asian women, men’s adventure mags generally avoided such topics.56 Likely, storylines bringing overly sexualized foreigners back to the United States would have aggravated Cold War racial insecurities. Besides, it would have taken great narrative skill from the pulp writer, and a leap of faith from the reader, to convert a woman from Peru’s “Forbidden Amazon Female Compound” into a domesticated American housewife. The two types of women were meant to be separated, in both fantasy and reality.57

Wartime prison camps also conveniently separated foreign women from American society. Here, pulp writers repurposed popular American captivity narratives dating back to the late 1670s with Mary Rowlandson’s abduction by Native Americans during King Philip’s War. The possibility of a young white woman being sexually violated by a savage Indian clearly offended Puritan sensibilities.58 In the pulps, however, prison camps seemed more like carnal playhouses. Male captives might be sent to a Russian camp of “banished wives” or be caught in a Japanese “comfort girl” stockade, only to escape with a “glowing-eyed” beauty who sexually rewards her savior as anti-aircraft guns fire in the background. Stag even ran an exclusive, “Inside a Communist All-Woman Penal Camp,” that focused on “sex-starved females.” According to the article, “conversation and sexual intercourse” were the “two greatest pleasures of the poor and the imprisoned.” When a Russian infantry unit decides to bivouac near the Siberian penal camp, the prisoners gape at the bare-chested soldiers, a few women breaking out, not to escape, but to rush across a stream and throw themselves at the waiting men who take them to “love nests in all directions.”59

Not surprisingly, these camps were perfect locations for heroic warriors to liberate. In one True Action offering, undercover CIA agent Joe Coogan breaks into a wilderness stockade of “captive blondes,” the “passion prisoners” being held by former Nazi henchmen. When their rescuer reaches the camp, the “dozens of young, attractive girls” become “Coogan’s playmates,” as they are “starved for attention and even a superficial love.”60Male served up a similar tale, this one set on a Turkish penal plantation where women are forced to participate in wild parties. The only American prisoner, Jessup, is amazed to find thirty female internees. As a guard tells him, “thank Allah. It would be a very dull place without them.” Not long after his capture, the American earns a spot on the household staff, the commandant’s “blonde favorite” seeking him out for a quick love-making session that is filled with “explosive savagery.” Yvette then hatches an escape plan with Jessup that involves poisoning the guards. Leaving the prison courtyard a “ghastly carnival grounds,” the American leads the refugees to safety in Syria, though he loses Yvette along the way, rumored to have become the mistress of a British general. “She always did attract men at the top,” Jessup utters.61

While Siberia and Turkey may have been trendy locales for pulp writers, they paled in comparison with Nazi Germany, perhaps the most common setting to mix sex with war. Looking back, the macho pulps blatantly misconstrued the ways in which American soldiers and German civilians experienced sexual violence both during and after the war. Wartime incidents of looting, destruction, and rape were common after the arrival of GIs. In the spring of 1945, instances of rape far exceeded contemporary civilian rates back home in the United States. Postwar occupation forces acted no better. According to one source, between “May 1945 and June 1947, the Army recorded nearly 1,000 rapes by American servicemen in Europe.”62 It seemed as if sexual violence had become a routine part of the allied drive toward Germany’s unconditional surrender. Without doubt, American GIs’ rape of German women demonstrated a power differential between victor and vanquished. This was more than just men seeking female companionship.63

The adventure mags, however, told a far different story, one in which German women, often with whip in hand, held sexual authority. Most pulps downplayed the more unseemly tendencies of GIs, instead placing them in the role of victim. The melodramatic presentation of female SS sadists seemed to resonate with men already anxious about their sexual status, no doubt in ways unintended by pulp writers. One former photo editor for a national men’s magazine recalled how his own “early rape fantasies were to imagine raping the female Nazi camp guards, slowly and with great relish. I was doing it to righteously punish these vicious blond Brunhildas for what they had done to others.” Of course, not all young readers so directly fantasized about sexual violence based on these phantasmatic renderings of Nazi prison camps. At the same time, however, the pulps openly intended for the “sadistic burlesque” to thrill and arouse.64

Ilse Koch ranked as the most sensational perpetrator within the “Nazi-with-whip” genre. Married to Karl Koch, commandant of the infamous Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany, Ilse gained a notorious reputation for sexually abusing and torturing prisoners. The pulps took note. Battlefield described the “bitch of Buchenwald” as a “reddish-blonde beauty” who would swagger around camp “provocatively attired in halter top and shorts, a heavy riding crop under her arm.” The magazine made sure readers knew that Koch, a clear “nymphomaniac,” had sadistically reversed normal gender relations in the camp. “Thousands of men were her slaves, could be forced to gratify every natural or unnatural whim and caprice.” As in the Jessup story, incoming prisoners who “struck her fancy were assigned to her house as servants. Their services consisted mainly of love-making.” While Battlefield noted how Koch was “guilty of the most atrocious crimes against humanity,” the article still spared readers from the worst of Buchenwald’s viciousness. Sex, it appeared, was more interesting than genocide.65

Real Men published a similar tale in late 1960, “The Lady with the Whip.” Here, an American GI is captured in North Africa after the battle at Kasserine Pass and tortured by Inga Karel, an officer in the Hitler Jugend. She is paradoxically the most beautiful woman the soldier has ever seen, and the only one he loathes with every fiber of his body. In the story’s climactic ending, Inga engages in the “most exquisitely refined torture,” sexually tempting the American even though he detests her. She undresses in tantalizing fashion and then whips her victim, demanding that he make love to her. Only after tanks from Patton’s Third Army burst into the camp is he saved, our hero killing his captor by fashioning a noose out of the prison fence’s barbed wire. “Inga was right,” he declares as she lay bleeding. “There is a great deal of pleasure in inflicting pain – on those you hate.”66

Fig. 3.8 Battle Cry, August 1962

For younger, sexually inexperienced readers, these stories must have been discomfiting. Ilse and Inga plainly were despicable people. Yet they were beautiful and lascivious at the same time. Were all female enemies so lustful? The macho pulps certainly made German women seem so. In a story evocative of an X-rated version of Hogan’s Heroes, “Lusty Ludwig’s Love Lager,” a POW camp commandant promises to throw a party if his allied prisoners do not try to escape for a whole month. The scheming POWs accept the deal, as long as “Munich broads” are invited to the festivities. Both sides fulfill the bargain, and what ensues is a “scene from a Hollywood production of a German orgy.” The event seems less surprising given other pulp stories in which top German generals kept scores of mistresses, some of the “lushest, most beautiful women in Europe.”67 Maybe the ugly side of war wasn’t so ugly after all.

If Hitler maintained brigades of “man-hungry” women in the German army, adventure magazines suggested men actually might enjoy the act of being sexually exploited. Sharp differences separated men’s fantasies of becoming the sex slave of a warrior priestess or sadistic Nazi and a woman being raped by savage tribes, the former far more acceptable, even desirable, than the latter. Indeed, these men seemed to relish being sexually assaulted. A story on the liberation of Paris noted how a tall, muscular American sergeant “was literally raped by two girls in a café in the Rue Lauriston.” A purportedly autobiographical account in True Men followed a Polish Canadian sold to “love-hungry” women in Madagascar, part of a modern-day male slave market.68 For Men Only equally featured a 1966 story in which a Yank adventurer lands in the unexplored jungles of Guatemala, where “for 200 days he was forced to be king and – for 200 nights the ‘love slave’ of a female army.” Naturally, the tribal priestess, a “woman of tremendous beauty,” demands sex, the American complying and “leaving her utterly exhausted.” Thus, even in captivity, real men could demonstrate their masculinity, strength, and endurance, bringing balance back to narratives wherein female captors had violated cultural prescriptions limiting overly aggressive, sexual behavior.69

In this way, gendered fantasies incorporated bondage narratives and sadomasochistic plot devices as yet another way of demonstrating that war and sex, ideally intertwined, were the most effective man-making experiences. If prisoners could endure their captivity and torture with dignity, they would prove their worth as men. If, in the process, they also could demonstrate their superiority by withstanding the worst of female sexual advances, all the better. Moreover, “a great deal of research” suggested that assertive women did not mind being assaulted in return, one psychologist in Man’s Life claiming it was a fact “that about one in every eleven women possesses a streak of masochism to an extent that she positively requires some sensation of pain in order to achieve sexual relief.”70 The message rang clear. If GIs violated women in a wartime setting, chances were good the soldiers’ victims had been hoping to be punished anyway.

For fictional war heroes, enduring pain – even if pleasurable – while at the mercy of a sexually voracious woman became yet another display of masculinity. Even wounded soldiers could perform sexually. In Vietnam veteran Larry Heinemann’s Paco’s Story, the novel’s protagonist, though grievously wounded, receives oral sex from his nurse. (Only later do we find that Paco’s platoon had raped a fourteen-year-old Vietnamese girl, the source of his emotional troubles.)71 Fellow vet James Webb’s Fields of Fire includes a marine ambulatory patient who empties “his anxieties into a half-dozen Japanese whores.” Finally, in Men, Mario Puzo’s short fiction story “The Seduction of Private Nurse Griffith” finds the hero convalescing in a VA hospital, all the while longing for a nurse who is a “dazzling, full-bodied goddess of a Florence Nightingale.” Ultimately, his dreams are “made flesh” and the two share a night of passion that GI Pete “had never known and would never feel again.”72 In each of these stories, wounded soldiers somehow retained their sexual proficiency despite their wartime injuries. Was there any better way to define a man’s virility?

The pulps’ fantasies of “savage” women hence played upon a “dominance/submission dynamic” that ultimately sought to reinforce Cold War gender roles. Villainous Fräuleins or man-hungry slave traders might challenge conventional norms, but only until the story’s climax. In the end, male heroes won the day, any assaults on captive men ultimately morphing into heterosexual intercourse in which the man dominated a subordinated woman. Sheer manliness triumphed, with sexual conquest as the reward. That these men could prevail over Nazi dominatrices or savage tribal leaders seemed to make victory all the sweeter. The same might be said of besting women strong enough to fight alongside men in battle.73

The Sexual Warrior

Comic books, a parallel form of Cold War popular culture, contained few, if any, storylines explicitly blending war with sex. After facing charges from politicians, and critics like Fredric Wertham, that comics were corrupting America’s youth, publishers sought less controversial topics in the hope of increasing flagging sales. Still, superhero and war-themed comic books did introduce young readers to a genre showcasing extreme battlefield heroism and, in some instances, violence against women. The two, however, usually remained separated, at least in war comics. The popular DC character Sergeant Rock never performed as a sexual conqueror, usually too busy fending off German tanks or assaulting heavily defended enemy positions. When women did enter the story, often as army nurses, they more often than not served as damsels in distress rather than love interests. In the comics, Sergeant Rock and his fellow Easy Company infantrymen exceled as near-superhuman warriors, but as asexual ones for sure.74

Nevertheless, women did suffer at the hands of comic villains. In Phantom Lady No. 21, for instance, the female victim is shown wearing nothing but lace underwear as she is strangled to death by the evil Chessman. Wertham railed against these frequent renderings of women tied up “in all kinds of poses, each more sexually suggestive than the other.” Even heroines like Wonder Woman and American intelligence agent Señorita Rio often had their bodies shackled by outlaws, the disturbing “masturbation fantasy of a sadist” in Wertham’s mind.75 Equally depraved, complained critics, were the artists depicting female bodies with exaggerated features, their large breasts, known as “headlights,” making “young girls genuinely worried long before puberty.” Wertham, in particular, fretted that child readers would confuse “violence with strength” and “sadism with sex.” While war and sexual violence may not have intermingled as vividly in the comics as they did in the macho pulps, the two themes certainly were present in Cold War era cartoons.76

If writers regularly placed heroines like Phantom Lady in compromising positions, it seems plausible that comics prepared young readers to become more receptive to similar storylines in men’s adventure magazines. Yet it also is important to remember that Wonder Woman served alongside her male colleagues in the Justice Society. So too in the macho pulps did women fight next to men. More than just passive sexual objects, women warriors engaged in combat, albeit not in traditional roles like frontline infantry or armor units. Rather, as underground saboteurs, double agents, or “girl commandos,” they could participate in war without fully challenging conventional gender constructs.77

While male fantasies of armed female combatants may not have involved the victimization of helpless women, they did suggest the desire to dominate strong female figures. Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale character Vesper Lynd, for example, supposedly was based on World War II British Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent Christine Granville. Despite Granville’s impressive wartime accomplishments – born Maria Krystyna Skarbek, she worked in Eastern Europe helping build the Polish resistance – Fleming’s character adaption of her is both as lover and as double agent. In the Bond novel, she retains her role as seductress. Granville may have found her time in the SOE liberating, but her story ultimately promoted postwar martial masculine values rather than upsetting any hierarchical power structures in the long term. That Bond could successfully entice such a strong woman only burnished his own credentials as a man.78

The pulps maintained this gendered narrative, mostly by locating women in resistance units behind enemy lines. There, they could more easily use their bodies to seduce, as in one story where a Norwegian “resistance blonde” leads evil German officers to momentarily forget the war, thereby upsetting Hitler’s bid to make an atomic bomb. An account in Men from a French resistance fighter shared how the movement relied on “brothel girls” and “chambermaids” to take advantage of their “unique opportunities” for gaining valuable information from German occupiers.79 Pulp writer Walter Kaylin took the co-ed war to North Africa, where the American hero, Anders, meets Miss Lily Murat, a former nightclub entertainer. Though at first he rejects her plans to create a local women’s auxiliary corps, he reconsiders after remembering that “Oyobe women frequently fought alongside their men in tribal wars and could probably assist a guerrilla unit in many ways.” While the female fighters perform courageously in combat, Anders clearly is in charge throughout as they hold off their German and Italian adversaries.80

What is more, the pulps indicated that most women were not cut out for war. In Man’s World, French milkmaid Françoise Mourant joins up to fight with the Americans after being raped by drunken German soldiers. She steals a GI uniform, transforming herself into a private from the US Army’s 28th Infantry Division. For the next month, Mourant fights alongside her unsuspecting comrades, even as they make fun of her “beardless jaw” and call her “Pretty Boy.” Only after being wounded in combat and evacuated to a field hospital is the masquerade uncovered. To the magazine, the lesson was obvious. Combat had persuaded Mourant that “war was no game for a woman.” Men’s place remained secure.81

On occasion, women did take up more traditional combatant roles in pulp war stories. The adventure mags, though, did not miss an opportunity to highlight their sexuality. In one World War II account on female pilots in the Soviet Air Force, artist Samson Pollen depicts sensual aviators rushing to an airfield in nothing but their revealing underwear. Their hair is perfectly coiffed, red lipstick on each woman’s face. The one pilot who is wearing a flight suit has it halfway unzipped, baring her cleavage as she wrestles with her parachute caught in an airplane’s prop wash. In the story, these lascivious Russians rescue an American B-17 bomber pilot, who makes love to one of his saviors after a vodka-laden celebration. After, as they prepare to undertake a combat mission together, he is amazed at how quickly the women learn to fly a US aircraft. Readers thus could share in the American’s voyeuristic fascination with these aces who were assuming a wartime role.82

In a late 1959 issue of Battlefield, Russian women fulfilled more time-honored martial duties. An autobiographical account from Kyra Petrovskaya chronicled her experiences as an army nurse and entertainer of frontline troops during the war. Caught in the siege of Leningrad, she fights against the Germans and is wounded in the process, not long after leaving the army and returning to her stage career. The magazine was sure to contrast a 1942 snapshot of Kyra in Red Army breeches and tunic with a postwar photo of her barefoot and in full makeup and flowery dress. Anything less would have challenged her customarily subservient role.83

While Petrovskaya reverted back to postwar life as actress and spouse, other Russian women stayed in the fight to finish off the Nazis. In “Battalion of Nymphs,” pulp writer William Ballinger left little doubt these female warriors were at once sexy and deadly. The “blood thirsty Amazons … carried bayonets strapped to their thighs and grenades under their blouses” as they set out to destroy the German high command. In battle, they rush forward “firing their rifles” and “screaming with rage, with exhilarating, mind-dazed anger.” The female commanders competently maneuver their units against the German invaders, while their soldiers are equally at ease with a machine gun or a Molotov cocktail. According to the story’s artwork, these warriors also fight with their tight-fitting tops tied in front so they can lunge bare midriff against their harried foes.84

Ballinger’s use of the term “Amazon” is instructive, for the macho pulps regularly employed the concept throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Like the exotic harems, Amazons too could be found around the globe, ensuring that adventurers could partake in the sexualization of war no matter where they went. In the jungles of New Guinea, Yank pilots shot down during World War II are captured by nude Amazon women, “female Tarzans” who torture the Americans until they make their escape.85 In Greece, US commandos team up with Ionian female divers who, like their Amazonian ancestors, are noted for their physical skill and “for leading a free-wheeling independent love life.” Adventure Life took the story to Tasmania, where a captive sailor avoids being killed and then boldly shames his captors. “I see you are not really warriors, but still women who kill best when their victims are tied to a stake.” Ultimately, he collects his own harem, successfully meeting both the military and the sexual challenges posed by the Amazon tribe.86

The global reach of Amazonian lore allowed pulp writers the chance for their heroes to best the “femme sauvage” wherever she lurked. Westerners could command battalions of “naked, love-hungry Amazons” in East Africa or fight against pygmy warriors in the Amazon itself, their women “as beautiful in their own way as any lighter skinned girl in the Folies Bergere.”87 This code-switching even took form in Southeast Asia, where an American pilot crashes behind enemy lines during the French-Indochina War. The Amazon women who take him hostage are a “band of torture-trained females currently terrorizing the border region of Vietnam.” The guerrillas are Hoa Hao, a quasi-Buddhist sect, apparently more warrior than monk. When the women strip their uniforms to cool off in a mountain lake, the American is struck by their “hard, young, athletic” bodies and the abrupt “transformation from grim young warriors to laughing young girls.” Without doubt, GIs fighting their own war years later equally would question if Vietnamese women were vicious fighters, sexual objects, or a dangerous combination of both.88

Not all women, however, were simple military instruments for male combatants. Some took matters in their own hands, especially when seeking revenge against perpetrators of sexual violence. Stag ran a 1961 story on a group of Yugoslavian girls and young women who were brutally raped by Italian occupiers in World War II. They band together after escaping and inadvertently run into a roadblock. One of them, Mila, opens the top buttons of her shirt to distract the guards before savagely bayoneting them to death. When they next reach a concrete blockhouse guarding an important crossroads, they successfully employ the same ruse, amassing weapons as they proceed. With each raid, the partisans become more adept at killing before teaming up with an American airman. Not surprisingly, the Yank takes more of a role in planning as Mila’s aggressiveness leads to casualties within the group. By story’s end, though, this “killer brigade” is capable of marching through difficult mountainous terrain with heavy machine guns on their backs and cases of ammunition in their arms. Despite deprivation and losses, the women Mila leads are ready to fight “to the last.”89

Mila’s tale reveals how easily war and sex could work in tandem within men’s adventure magazines. Strong warriors were sexual champions, plain and simple. Perhaps that is why Man’s Illustrated noted how US marines in Vietnam were “hopping mad” over the tactics of their army brethren in the Special Forces. According to the men’s mag, Green Berets were spreading rumors among “Saigon doxies and other Oriental dolls that Marines are impotent as a result of surgical operations designed to make them better fighting men, but ineffective in the sack.”90 The disassociation of military acumen and sexual prowess made the prank work, but also implied that US servicemen had embraced fully the heroic warrior–sexual conqueror paradigm.

If the marines indeed were miffed at being labeled impotent, it seems worth evaluating the power of heterosexual fantasies and how they are linked to aggression. The environment of war clearly legitimizes violence, an unrivaled place where men can wield massive power. Yet that power is not solely directed at enemy forces. In South Vietnam, the civilian population equally bore the brunt of hard fighting. In the process, if savage women posed a threat, a truism in the world of macho pulps, did war then offer men the chance to exorcise their fears? On an extended battlefield, where lines blurred between combatants and noncombatants, soldiers could be as aggressive as they wanted against the female population without concern of retribution. One American GI in Vietnam recalled not even desiring a prostitute because of the presumed availability of women. “You’ve got an M-16. What do you need to pay for a lady for? You go down to the village and you take what you want.” That soldiers could come back from their tours a “double veteran” demonstrated visibly the strong connective tissues between war and sex.91

It seems likely that adventure magazines encouraged adolescent fantasies combining battlefield aggressiveness, misogynistic attitudes, and domineering sexual behavior. Whether nymphs or Amazons, women in war were savage others, either prizes to be attained or challenges to be overcome. The macho pulps, however, suggested that these attitudes had deep cultural roots, influencing young readers long before they went off to war. Take, for instance, an advertisement in Brigade. Prospective buyers could mail in a coupon for “Sassy Stories,” a collection of “old-time French favorites” that included tales like “Assault and Flattery” and “Wife Beating – Evil or Good.” How many readers saw few if any distinctions here between sexual pursuit and sexual violence? Did ads like this intimate that some men were more aroused by physically subduing women than by engaging in non-violent, consensual sex? Or did these “Sassy Stories” help reify in men’s minds that they still commanded Cold War gender relations?92

Most likely, younger, working-class magazine readers did not plunge into deep theoretical thought exercises on the relationships between power and gender. The stories appealed on a more fundamental level. For many readers, they were simply entertainment. Yet these same stories must have established certain expectations about what war might be like as American men began to arrive in Vietnam. If Korea was any indication, there would be plenty of “love-and-money hungry girls” to obtain if the pulps could be trusted. In fact, as the Johnson administration debated the merits of sending US ground combat troops to South Vietnam, Male published an exposé on “Korea’s 800,000 Give-Give Girls.” The article included photographs of Asian women in heavy makeup, short dresses, and high heels, noting how they were a “major relaxation in a desolate oriental country.” In the story, a nineteen-year-old infantry soldier visits a local dance hall with “swarms of Korean B-girls, dressed in oriental slit skirts, black net stockings and skin-tight white jerseys.” The young Nebraskan enjoys the “most sensual night” he ever spent, conceivably making his overseas tour more than worthwhile.93

Eighteen months later, as US forces were fighting across the embattled South Vietnamese countryside, For Men Only implied that militarized sexual fantasies still might resonate among its readership. In its September 1966 issue, the magazine considered the “Ten Best Draftee Deals in the Armed Forces.” After listing out benefits such as education, medical and legal aid, and travel, the article noted how overseas duty offered “a number of distinct advantages. First, there are the babes.” While there were “nice American girls” working abroad, most GIs, according to the author, preferred the “not-so-nice foreign girls.” The final “deal” was Vietnam. There, new recruits apparently could find a “sense of adventure and patriotism,” including the chance to experience combat and share “ordeals and triumphs with their fellow Americans.” Unironically, the piece ended on an uplifting note: “if you are one of those selected for duty in that far-flung area in which America is defending freedom at a heavy cost, you may be getting the best deal of all!”94

On the verge of US combat troops deploying to Vietnam, a precedent had been firmly established in the cultural milieu of working-class pulp readers. Men’s magazines had helped create a narrative where heroic warriors were not only battlefield victors, but sexual conquerors as well. An idealized version of manhood – however warped it may have been – appeared enticingly within reach. Yet a predicament quickly emerged in the villages and rice paddies of a distant country locked in brutal civil war. Pulp readers now in uniform soon found that the reality of fighting in South Vietnam ran far afield from the fantasies that seemed so convincing in sensational magazines built upon sex and adventure.95