In 1928, Franz Lehár announced a new operetta to premiere in Berlin: Friederike, in which his recent collaborator, tenor Richard Tauber, would play the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in a story of a brief fling dating from the poet's student days. The work's appeal was described floridly in an anonymously authored Festschrift released to celebrate both the premiere and Lehár's twenty-fifth year in the operetta industry (even though it was truly his twenty-sixth):

Beloved idyll of Sesenheim, emerge again from the shadow of the romantic past! … Time of love, time of promises, time of love stories, time of world-weariness, reveal your silhouette! Reassume a visible form, and for a few hours in the theatre surround our senses with the fog of your soft, gently drifting air.Footnote 1

The language promises that audiences will be treated to a multisensory experience in which they will leave modernity to spend a few hours in a hazy, idyllic past. Such effusiveness characterised Lehár's late musical style as well: he favoured lush strings, operatic vocal technique and surging melodies rather than the fashionable Schlager and dance styles of competitors such as Emmerich Kálmán, Oscar Straus and Bruno Granichstaedten, or rival genres such as the revue.

Some were alarmed at the prospect of a commercial operetta theatre putting the most hallowed figure of German literature onstage. ‘One is speechless over the idea’, noted operetta librettist Alfred Grünwald in a private memoir.Footnote 2 Later, when celebrating the operetta's hundredth performance, Lehár claimed that he had had much the same reaction himself when the librettists Fritz Löhner and Ludwig Herzer had proposed the idea: ‘For no price!’ he reported that he had cried, ‘I haven't gone crazy yet!’Footnote 3 Audiences were similarly sceptical: letters of protest were written to Berlin's Akademie der Künste demanding an official response, and the operetta eventually had the distinction of troubling both Ernst Bloch and Josef Goebbels.Footnote 4

Yet, I will argue, Friederike is not only readily legible as an operetta but was a logical continuation of Lehár's aesthetic project. Written during a time associated with aggressive modernity, Friederike was an attempt to write a backward-looking operetta under the mantle of an invented classicism. By 1928, much of Berlin's theatrical fashions tended towards revues and their chorus girls, foxtrots and Americanisms of both plot and music.Footnote 5 Lehár's operetta, however, is a rural idyll set outside Strasbourg in the 1770s, telling the well-known story of the young poet's failed romance with the titular Friederike Brion. It ends with her (fictional) noble self-sacrifice: the renunciation of the poet's affections as he leaves to join the Weimar court, destined for fame. The libretto is a bricolage of fictionalised biography, Goethe poems, borrowed tropes from stories by Goethe and odd guest appearances. Lehár thus opposed prevailing trends and instead claimed that his own style had achieved classic status. Lehár proclaimed that Friederike was an exercise in restraint and control. ‘It would be’, he wrote in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, ‘a wholly small Singspiel, set only for a chamber orchestra … I felt that it was an experiment.’Footnote 6 A few years into his Berlin period – in a city that in 1928 was still booming and boasted commercial theatres more lucrative and stable than those of Vienna – he had left behind his famed Hungarianisms and, according to critics, gone German.Footnote 7 If Weimar Berlin has been celebrated as Dionysian, with Friederike Lehár made a claim for himself as a populist Apollo.

Friederike was a popular success, but its mixture of aspirational German cultural symbols and the tropes of commercial operetta have proved challenging for scholars and critics alike. In this article, I will argue that Friederike's style and discourse can be productively considered as an example of the middlebrow, a category not often applied to German art. This lens can reveal tensions and ambivalences often obscured by the more traditional Germanic division of art into a binary of high and low forms. Rather than describing Friederike as a would-be opera, considering it as middlebrow illuminates Lehár's strategies to cultivate a particular form of bourgeois prestige in a musically retrograde style not fully congruent with a binary view.

Scholars and popular culture have celebrated Weimar Republic-era Berlin for its avant-garde and transgressive tendencies, and its culture is almost inevitably viewed through the lens of innovation. In the collection Weimar Thought, Peter Gordon and John McCormick typically give Weimar culture enormous credit: ‘to a remarkable degree, much of the literature we now regard as foundational for modern thought derives from a single historical moment: the astonishing cultural and intellectual ferment of interwar Germany circa 1919–33’.Footnote 8 Other critical accounts often invoked in Weimar studies, such as Miriam Bratu Hansen's 1999 article and influential coining of ‘vernacular modernism’, have emphasised the forward-looking tendencies even of popular culture.Footnote 9

Friederike appears anything but forward-looking, which is part of why it has long been dismissed as a misbegotten experiment. But Friederike reveals a middlebrow paradigm which fills in some gaps in scholarly pictures of Weimar culture. The traditional Germanic taxonomy of high and low art pervades Friederike's reception and Lehár's own writing about operetta. However, drawing on work on middlebrow culture by Joan Rubin and Christopher Chowrimootoo, I will show how Lehár's proclamations of artistic ambition and simultaneous desire for popular success – as well as his interest in overwhelming sentimentality and high literature – are not in conflict. At a time when operetta seemed to be losing popularity in favour of revue and film, Lehár's middlebrow strategy recognised that the genre itself was seen as old-fashioned and he sought to sell it as an example of respectable culture. Middlebrow studies, in other words, can enable a more inclusive and nuanced reading of the tensions within Weimar culture. It can also, I will argue, contribute to a more inclusive approach to operetta scholarship, one that acknowledges popular works like Friederike not as peripheral but rather as central to what German operetta was and what it meant to audiences.

I will first outline the landscape of middlebrow studies and Weimar historiography. Considering Friederike's score and libretto as well as the extensive documentation of its composition and reception in the Berlin press, I will then examine the many sources that contributed to Friederike and reveal it as a surprisingly ambitious, if eccentric, contribution to Goethe biodrama. Next, I will analyse the score's stylistic allusions and turn to Lehár's rhetorical positioning of his work in the Berlin theatrical scene. Finally, I will argue that operetta scholarship itself has traditionally been ill-equipped to deal with Lehár's late works and operetta more generally, and suggest that a middlebrow paradigm can contribute more widely to this discussion.

Towards a Weimar middlebrow

The phrenology-derived term ‘middlebrow’ originated in the early twentieth century. The concept (though not the word itself) is often attributed to a 1915 essay by American literary critic Van Wyck Brooks, who defined the ‘highbrow’ and the ‘lowbrow’ as types of people with contrasting points of view on life and argued the need for a middle category.Footnote 10 The term did not, however, come into wider use until the 1930s, when it circulated primarily in Britain and the United States. According to Margaret Widdemer's non-judgmental description, in 1933 the middlebrow was the ‘majority reader’ who was neither a tabloid addict nor an intellectual, ‘civilised’ and actively interested in cultural consumption.Footnote 11

In the following decades, however, the word's associations became more derogatory. Virginia Woolf described the middlebrow as ‘the man, or woman, of middlebred intelligence who ambles and saunters now on this side of the hedge, now on that, in pursuit of no single object, neither art itself nor life itself, but both mixed indistinguishably, and rather nastily, with money, fame, power, or prestige’.Footnote 12 In America, Dwight MacDonald's ‘Masscult and Midcult’ (1957), following in the steps of Clement Greenburg's work on kitsch, transformed the middlebrow from a person to a category of texts that ‘is not just unsuccessful art. It is non-art. It is even anti-art.’Footnote 13 For MacDonald, middlebrow art removed art's challenge and confrontation, instead providing a product that was easy to digest and industrially mass-produced (like low art) but with an element of self-conscious prestige for the nouveau riche and middle class. Most of these critics came from the highbrow and partially respected the low for its perceived cultural authenticity; in their minds modernist art was perpetually threatened. In MacDonald, this threat is most perniciously represented by the ‘midcult’, a form of the middlebrow that attempts to pass itself off as the real high cultural thing: ‘it pretends to respect the standards of High Culture while in fact it waters them down and vulgarizes them’.Footnote 14

In recent decades, scholars in multiple fields have rehabilitated the middlebrow as a neglected category. In 1993, Joan Rubin wrote in The Making of Middlebrow Culture that the subject had been ‘disregard[ed] and oversimplif[ied]’ and that scholarship could ‘contribute to the redrawing of the boundary between “high” art and popular sensibility’.Footnote 15 In music, this challenge is still an important one: in 2018 Christopher Chowrimootoo wrote that while musicologists have grown far more cautious about binaries, ‘modernism's divisive legacy lives on in sometimes subtle, sometimes not-so-subtle ways’ in which modernism retains a degree of prestige. Yet the middlebrow, Chowrimootoo suggests, has the power to cast light on ‘those institutions, artists, critics, and audiences that – more or less consciously – sought to mediate [the] supposed irreconcilable oppositions’ between a twentieth-century modernist and popular art.Footnote 16 Existing in the space between opera and vaudeville, operetta is an ideal site of the middlebrow.

There is, however, no standardised translation of ‘middlebrow’ in German, an indication as to how infrequently the concept has been invoked. Three different popular German–English dictionaries give three entirely different suggestions, none of them conveying the full valences or the problems of the English term.Footnote 17 In German art, the binary still reigns supreme: there is E- (ernste, serious) and U- (Unterhaltung, entertainment). The former is high art, the latter pure consumerism.Footnote 18

That is not to say that German studies scholars have not explored cracks in this binary. However, they have usually focused on interactions between the avant-garde and the popular rather than any conservative or bourgeois middle. Friederike was an immediate contemporary of – and in terms of first run ultimately longer-lived than – the most famous example of this mixture, Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill's Die Dreigroschenoper. Andreas Huyssen's After the Great Divide and Hansen's vernacular modernism laid the groundwork for numerous studies of intersections between an emerging avant-garde and popular culture in Weimar Berlin.Footnote 19 Hansen argued for a broader definition of modernism, one that ‘encompasses a whole range of cultural and artistic processes that register, respond to, and reflect upon processes of modernization and the experience of modernity … not reducible to categories of style’.Footnote 20

But the non-existence of ‘middlebrow’ in the German language does not mean that such cultural spaces didn't exist. As Friederike will demonstrate, operetta was well-positioned to evade a clear E- and U- classification. Operetta mediated between the Bildung of high bourgeois culture and the populism of U- without fully belonging to either, its motivations and presentation full of tensions and contradictions. (Hansen's modernism may be a big tent, but Friederike still remains an unlikely occupant.) Friederike and her ilk have, often, been poorly served by music scholarship, which has traditionally dismissed them on aesthetic grounds as sentimental and retrograde.

On a more general level, a Weimar middlebrow is an intervention in German historiography. The Weimar period has been glorified as a brief, charismatic golden age of culture amid disastrous economic and political currents (‘glitter and doom’ being one famous coinageFootnote 21). But, as a number of scholars have recently argued, disproportionate focus on the avant-garde of Weimar has obscured the prominence of more conservative cultures and reduced a complex tapestry to a small, elite group. Karl-Christian Führer summarises the issue as follows:

Our understanding of Weimar culture is incomplete without a grasp of broader patterns of cultural production and consumption, and skewed if it does not take into account the conservative tastes and the forces of tradition which also characterized it. Seen from this broader perspective, the cultural life of the republic emerges as less spectacular and less experimental than it appears in many accounts.Footnote 22

More recent accounts of Weimar culture and politics have tended to emphasise differentiation and fragmentation. They are less likely to label the Weimar Republic as doomed from the start and less likely to represent the culture in undilutedly positive terms.Footnote 23 In music, Nicholas Attfield highlights composers such as Hans Pfitzner and Alfred Heuss, arguing that they constituted a more conservative group that had been neglected, because ‘the historiographical deployment of “Weimar culture” necessarily performs a marginalization’ of those who were not avant-garde – a marginalisation inconsistent with their prominence in their own time.Footnote 24

The careers of composers such as Pfitzner – and Lehár – during the Weimar Republic have also become inextricable from their future reception and roles in the Third Reich. For operetta, this relationship is a complicated one, because in the simplest terms operetta performances remained extremely popular through the Third Reich while most of the authors of those same works (including Lehár's librettists) faced exile, imprisonment or murder.Footnote 25 As will be considered in more detail in the final section of this article, operetta is another argument against flattening Weimar studies into good and bad actors based on aesthetic or political judgment, and for considering the full spectrum of cultural production in all its complexity.

Poetry, truth and Friederikenliteratur

The plot of Friederike concerns a romantic episode early in Goethe's life. In 1771, the poet, then finishing his dissertation in law, travelled from his university in Strasbourg to the small village of Sesenheim in the company of his friend Weyland. There – in the operetta's version – he fell in love with Friederike Brion, the daughter of the village pastor, and after nearly becoming engaged, left her. Librettists Ludwig Herzer (1872–1939) and Fritz Löhner (1883–1942) named as their primary source Goethe's autobiography Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit (From My Life: Poetry and Truth, 1811–14 and 1830–1), which they supplemented with secondary literature, including letters of Goethe, Herder and Lenz and the ‘around 30’ monographs dealing with Goethe's time in Sesenheim.Footnote 26 A survey of the catalogue of the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in Weimar suggests that this number is surprisingly accurate: by 1928, there were indeed around thirty monographs whose primary subject was Friederike Brion.Footnote 27 Friederike combined the muse status of Beethoven's ‘Immortal Beloved’ and Shakespeare's ‘Dark Lady’ with a much more concrete historical record, making her a popular obsession. Herzer's description of their research, however, gives a deceptive impression of historical accuracy. While some of the fruits of research beyond Dichtung und Wahrheit are evident, the plot of the operetta makes major departures from both the memoir and the historical events described in the thirty books.

But the intermingling of historical research and fiction began with the poet himself. As suggested by the title, Dichtung und Wahrheit is an embellished memoir, whose mixture of poetry and truthful events has occupied Goethe scholars for generations. The Friederike episode, found in Books 10 and 11 (the last section of Part Two and first of Part Three, respectively), is particularly wreathed in sentimental and misty images. While Goethe certainly did travel to Sesenheim and meet Friederike (and wrote the poems now known as the ‘Sesenheim-Lieder’), much else about the episode is unverifiable or identifiable as literary conceit. The Brion family is modelled on Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield, published in 1762. Goethe reproduced the detached and ambiguously ironic stance of Goldsmith's narrator towards the naïve rural folk, something eliminated in the operetta.Footnote 28 Goethe's first-person narrator and his intellectual colleagues are rounded characters (and urban sophisticates) while the country folk of Sesenheim are idealised pastoral types in peasant dress.Footnote 29

As suggested not only by Goethe's own recording but also by the existence of dozens of monographs, this episode had already been widely popularised, studied and sentimentalised. Helga Stilpa Madland argues that this was in part a result of ‘psychological aesthetics’, that is, ‘a notion of spontaneity that equates work with personality, an explanation of the nature of art which allows scholars to posit and study the psychic activity from which a work arises in the belief that this will reveal its meaning’.Footnote 30 Studying Friederike, the earliest of Goethe's failed romances, then, might unlock nothing less than Faust and Die Leiden des jungen Werthers. This is, arguably, a middlebrow attitude itself in its narrowly biographical interpretation of literature, and treatment of art as a rational puzzle to be solved. It reflects a turn towards both biographical criticism (similar to what Mark Evan Bonds has identified as ‘the Beethoven syndrome’ in music) and the theatrical structure of the well-made play, which formed the basis of operetta librettos.Footnote 31

In most of its many tellings, the story assumes a romantic and sentimental but ultimately bittersweet aspect. This prelapsarian tale is gentle compared to Goethe's relationship with Charlotte Buff of Werther fame only a short time later (published 1774); indeed, the motif of a learned man beginning a relationship with and then leaving a young woman of lower social standing has another obvious parallel in Faust, Part One. Madland argues that in Dichtung und Wahrheit Goethe ‘took his referents from fictional representations in order to visualize for his reader what he saw and what effects it had on him’, making it less a fictionalised biography than a biographised fiction.Footnote 32 If tragic Faust and Werther are the stuff of opera, perhaps it is unsurprising that Friederike would be designated for an operetta. This sense of chosen modesty was essential to the operetta's effect.

Librettists Löhner and Herzer moulded Goethe's memoir and the various historical sources into the Procrustean bed of an operetta libretto, choosing, rearranging and creating events to conform to the standard model that dominated twentieth-century Viennese operetta composition.Footnote 33 Like many operetta librettist pairs, they divided their work: Herzer specialised in spoken dialogue and overall architecture while Löhner wrote the song texts. (Löhner also wrote cabaret song texts under the name ‘Beda’, most successfully ‘Ausgerechnet Bananen’, the German translation of ‘Yes, We Have No Bananas’, and was sometimes credited as Fritz Löhner-Beda.Footnote 34) Even though the creators of Friederike rejected the label of operetta, all the expected dramatic elements can be found in their customary locations. Goethe and Friederike are the leading couple; the second couple, receiving more comic material and dance music, is led by Friederike's sister Salomea, fictionally torn between Goethe's friends Weyland (medical student, present in Sesenheim) and Jakob Lenz (poet and theologian, notFootnote 35). The first act ends with a happy resolution and there is a dramatic reversal of fortune in the second-act finale.

The ambiguity of Goethe's departure from Sesenheim was unsuited to the dramatic confrontations required by the operetta form, and it is here that the librettists made some of their most drastic changes from the historical record (such as it is). In Act II, Goethe receives a letter appointing him court poet in Weimar, but he is told that the life will not afford the personal time to live with a wife. Friederike is broken-hearted but gives him up in a Marschallin-like gesture of renunciation. He leaves Sesenheim for Weimar. In reality, Goethe did not receive the Weimar appointment until well after severing ties with Friederike. The probable truth of the Sesenheim incident reflects poorly on Goethe and inflicted much more damage on Friederike's life than the operetta or Dichtung und Wahrheit admits; his relationship with her was probably considered tantamount to an engagement and his sudden departure grievously harmed her social standing. She never married, possibly not out of a broken heart but due to an irreparably damaged reputation. It seems that Weyland was shocked by Goethe's actions and never spoke to him again.Footnote 36 In the operetta, however, Herzer and Löhner gave their Goethe an honourable exit by sending him to the Weimar court almost four years early, skipping over l'affaire Charlotte Buff entirely and letting him say his farewells in person (where he obtains Friederike's permission to leave) rather than by letter, as he did in reality. Even as the operetta centres on Friederike rather than Goethe – though more out of the need for an audience surrogate than any interest in her interior life – it does not question his motivations. The representation of artistic creation and the demands of an artistic life are generic and unexamined; the operetta presupposes Goethe's greatness and importance in a way unsurprising in German culture but also typically middlebrow.

In most operetta third acts, the Weimar court's low prioritisation of work–life balance would be revealed as a misunderstanding and Friederike and Goethe would be happily reunited. But in keeping with Lehár's renewed penchant for sad endings (which he had first explored with Zigeunerliebe in 1910) and with the historical record, the librettists keep the lovers apart. In the operetta's invented Act III, Goethe, now famous, meets a still-single Friederike in Strasbourg eight years later. When recalling his happy days in Sesenheim, Goethe recognises the sacrifice she made for him. But, she says, now he and his work belong to the world – and thus in part to her. In Ethel Matala de Mazza's canny allegorical reading, this is the librettists’ statement of purpose: the sentimental Schlager (hit songs) of Friederike are what operetta can give Goethe, and Goethe through Friederike's eyes is the Goethe that operetta can offer.Footnote 37

Dramatic models

The librettists touted their historical research, but Friederike had other influences, which were part of what gave it an immediately accessible and familiar form. The odd mixture of sources reflects the omnivorous cultural tastes of Herzer and Löhner-Beda, but also Friederike's ambiguous cultural register. The borrowings read more as statement of purpose than plagiarism and many are even described in the Festschrift as signalling the work's intentions and supposed peers.

The first and perhaps most obvious of those peers is a popular play. As many critics of the time noted, the operetta's novel Act II finale and invented Act III draw heavily from Wilhelm Meyer-Förster's 1901 Alt-Heidelberg, one of the most performed German-language dramatic works of the early twentieth century.Footnote 38 In the play, a prince named Karl-Heinz disguises himself as an ordinary student to go to university in Heidelberg and falls in love with Käthe, the daughter of the local innkeeper, but must suddenly leave her to become king, only to have a nostalgic and bittersweet reunion with her in Act III. It is a sweet, slight comedy which appealed to an audience similar to that of Lehár. References to its plot required no explanation at the time; even Ernst Bloch's negative appraisal mentions ‘a vicar's garden in Old Heidelberg’.Footnote 39 The author of the Festschrift noted the similarity with affection: ‘The only difference is that here Karl-Heinz is called Johann Wolfgang, and Käthe is Friederike. And Heidelberg is Strasbourg.’Footnote 40 An early cast of the play included a Richard Tauber in the supporting roles, most likely the tenor Tauber's actor father.Footnote 41 The play was musicalised several times over, most famously by Romberg in his 1924 Broadway operetta The Student Prince (there is no evidence Lehár knew it, though it is possible). The younger Tauber starred in an earlier operatic adaptation by the Italian composer Obaldo (Ubaldo) Paccierotti, Eidelberga mia!, performed in German as Alt-Heidelberg.Footnote 42

But the librettists were also careful to signal their work's debts and parallels to classics of German literature, taking advantage of various works by Goethe. The libretto creates Goethe from the start less as a historical figure than as an extension of the nebulous chimera of Dichtung und Wahrheit, an amalgamation of ‘Goethian’ characteristics. The Festschrift celebrating the operetta also noted the opening's similarity to a section of Faust, Part One.Footnote 43 But – alas for the claims to German high culture – the similarities come into much sharper focus when Goethe's Faust is replaced by Act III of Charles Gounod's operatic Faust, something the Festschrift neglects to mention, and which moves the operetta into the territory of another popular, frequently maligned Goethe adaptation.

The sequence of scenes in the play becomes, in both play and operetta, a single daytime garden scene. In the operatic Faust, Act III, Faust enters, leaves his gift for Marguerite, and sings an ode to her house and the beauties of rural nature that have raised her (‘Salut, demeure chaste et pure’), an episode with no equivalent in Goethe's play. Then, alone, Marguerite sings her ballad (‘Il était un roi de Thule’) and discovers Faust's gift, singing about that as well (‘Ah! je ris de me voir!’). In Friederike, Friederike first sings a generalised song proclaiming the beauty of the sunny day (no. 2, ‘Gott gab einen schönen Tag’Footnote 44), then receives Goethe's gift of a decorated book of poems from the postman and sings another song about it (no. 3, ‘Kleine Blumen, kleine Blätter’). The following number is a students’ march straight out of Alt-Heidelberg (the presence of crowds of students in Sesenheim, not a university town like Heidelberg, is unexplained), but then Goethe enters and sings an aria extolling the beauties of Sesenheim and nature in general as they relate to Friederike (no. 5, ‘O wie schön, wie wunderschön’).

‘O wie schön’ and ‘Salut, demeure chaste et pure’ are remarkably similar in dramatic context and text. In both arias, the Goethean hero strolls in alone to admire the house of his beloved, contemplates the wonders of nature and the potential for an imminent appearance of his beloved in the midst of the flora. (It also recalls ‘Ô nature, pleine de grace’ in Jules Massenet's Goethe opera Werther, which like the Friederike version marks the male protagonist's first entrance and begins with a long orchestral introduction.) Yet if the text marks the moment as pastoral, this association is somewhat undermined by Lehár's decision to set ‘O wie schön’ as a waltz (‘langsamer Walzer’ according to the tempo marking) in the operetta version. Despite a typically pastoral oboe and other woodwinds, the idiom pulls the number away from a rural idyll and back towards the urban world of operetta.

But another more provocative and surprising allusion occurs before this, at the very beginning of Friederike. As the operetta opens (score no. 1), Pentecost church service has just ended and the minister (Friederike's father), his wife and their elder daughter sit outside as the pipe organ plays the recessional offstage, establishing from the very opening the specifically German, Lutheran nature of the setting – even though Alsatian Sesenheim was, in both 1771 and 1928, located in France, something the operetta ignores, the real messiness of national borders proving no match for the most German of writers. (Despite Friederike's fame, Sesenheim has never been a site of literary pilgrimage and it is possible that many were not aware of its precise location.) Lilting above the hymn is the sicilienne-like theme from the overture that will eventually become Goethe's Act II song ‘O Mädchen, mein Mädchen’ (no. 13). In its opening mixture of sacred Lutheran hymn and love music, the score recalls another German work in which a poetic, elevated stranger arrives in a rural town: Richard Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, in whose opening Walther von Stolzing spots Eva Pogner in church, and they chat over lightly scored music that in turn hovers over the sounds of an offstage organ hymn and church choir.Footnote 45 Unlike the allusions to Alt-Heidelberg, however, these operatic resemblances were not noted by critics (Edwin Neruda of the Vossische Zeitung mentioned Werther, but it is not clear if he meant the novel or the opera).Footnote 46 Yet they nevertheless contribute to Friederike's supposed ‘elevation’ beyond operetta, aligning Lehár not with the conventional and still-present three-act template of operetta, but rather with icons of the opera house.

Musical locales

The regional and historical colour is found in several places. The most prominent use of local colour is in the conventional large dance number found at the beginning of the second act. It contains two period-appropriate dances: an upper-class minuet and a more rustic Ländler, both appropriate to late-eighteenth-century Germany; a gavotte is also heard in the second-act finale (indicating the Weimar court for which Goethe will depart). However, Lehár was hardly a purist and he also composed a mazurka (no. 18a) and a polka (no. 18b), non-local dances more closely associated with operetta in general and Lehár in particular (several years earlier he had composed an entire operetta entitled Die blaue Mazur). Both are referred to in the libretto by semi-local names: the mazurka is proclaimed a ‘Pfälzertanz’, literally a dance from the Palatinate region, and the polka is proclaimed a ‘Rheinländer’.Footnote 47 However, the score is less coy. Lehár does, as already mentioned, compose the obligatory operetta waltzes. But he uses the dance thematically, associating it with Goethe and his poetry while Salomea and the other characters favour mostly rustic dances. Goethe's words and character are therefore marked – as urban, romantic, special – while Friederike's country life is ordinary.

Goethe's status is written into the operetta's casting of superstar tenor Richard Tauber in the role. Tauber had spent much of his career as a highly successful lyric tenor in major opera houses but found his fortune and enormous popular success by starring in Lehár operettas.Footnote 48 His role in Friederike was conflicted: his reputation as an opera singer continued to confer some of the high cultural prestige Lehár sought, while the cult surrounding him, according to others, had become a frenzy that was seen as crass, breaking the bounds of bourgeois propriety that Lehár had so ostentatiously imposed upon himself.

Vocally, Tauber outclassed other operetta performers. He could sing far higher, louder and with more musical variety and nuance than was the norm in operetta leading men (‘the vocal performance was at an almost unrivalled level’Footnote 49), but most importantly he lent Lehár operatic credibility. Tauber was thus an ideal partner for Lehár: his famous vocal artistry compelled his audiences to listen for and even fetishise musical detail and vocal tricks for their own sake – the same terms by which Lehár's score was praised. The Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, for example, described Tauber's ‘precious nuances’ and the Kreuz-Zeitung said he provided ‘the highest musical pleasure’; Der Tag claimed that he provided ‘veritable bacchanals of his musicality, his magical vocal technique, his amiability’.Footnote 50 This reinforced the discourse of Friederike as an artistic achievement and classic work rather than as an operetta entertainment, even as it continued to play by most of entertainment's rules.

By this point, Lehár had established a formula for Tauber's hit song. It would be found midway through the second act, begin loudly, as if in medias res (uncharacteristically for operetta), and contain operatic ascents into high vocal registers not often found in operetta. Its dramatic context would be general, so as to better secure its success outside the context of the operetta, and it would address a female as ‘du’. In Friederike, this song is ‘O Mädchen, mein Mädchen’, its text taken in part from Goethe's ‘Maifest’, from the Sesenheimer-Lieder. Like the abrupt opening of a Tauber-Lied, the song starts with the poem's sixth strophe, all four lines of it, but does not include any of the others, continuing with an original text. The Tauber-Lied was the emotional climax of a Tauber operetta, and in Friederike it dutifully became the operetta's biggest hit. Yet the Tauber-Lied was also an established formula, and to fulfil its role the song has to depart from the intimate character and restraint that Lehár frequently claimed was the operetta's defining tone. Despite its motivic integration, these departures and its generalised dramatic function – again necessitated by the established Tauber-Lied type – make it strangely disposable.

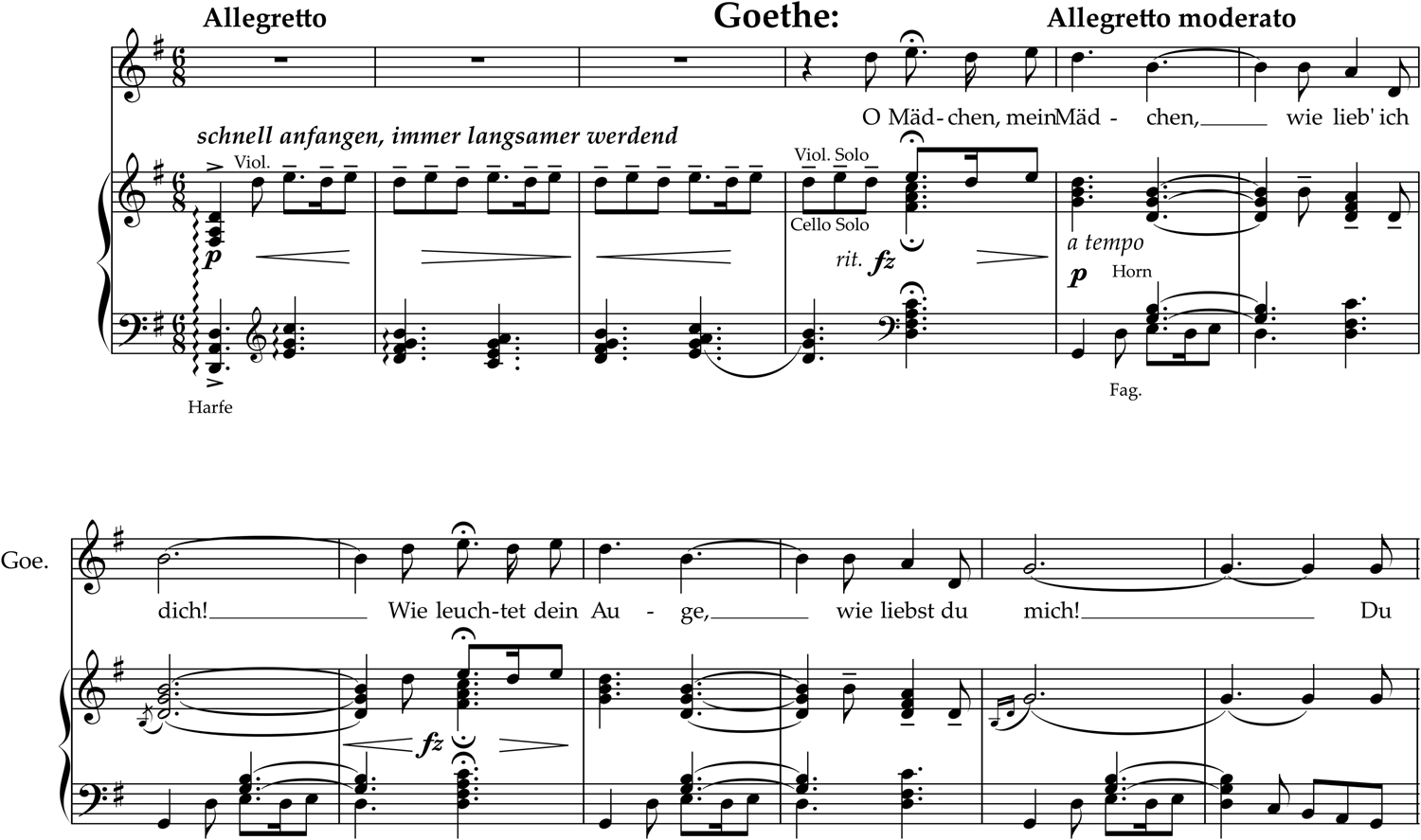

Lehár certainly worked to thread the song's motifs throughout the score. The score opens with the motif in a pastoral setting: in octaves played by flute, clarinet and bassoon, later joined by gently oscillating strings and harp (Example 1). This introduces the piece as intimate and small, unlike the traditionally thick and bombastic start of most operettas (e.g., Paganini, Der Zarewitsch, or any Kálmán operetta of the 1920s). The motif is heard again at the beginning of no. 1, in the Meistersinger parallel already discussed. But it is not heard vocally until the Tauber-Lied's traditional Act II spot, where it unfolds in all its glory (Example 2): the second note held with a fermata (allowing Tauber to stop the action and display his vocal quality), the simple orchestration now made colourful with a harp, multiple solo strings, and horn. What had been a simple neighbour motion in conjunct motion is now harmonically rich, with Tauber's E not a simple neighbour tone but the ninth added to the top of a dominant seventh. The simple world of Sesenheim might be monophonic but Goethe – and Tauber – demanded more.

Example 1. Friederike, Act I, Prelude, opening.

Example 2. Friederike, Act II, no. 13, ‘O Mädchen, mein Mädchen’, opening.

The audience reacted with customary astonishment and Tauber reprised the number four times. (The Tauber-Lied was referred to as a ‘da capo number’ by several critics and it is unclear – possibly intentionally – whether this refers to the rounded binary form of the songs or to Tauber's penchant for encores, usually called ‘da capos’.) Yet for all its excess, his very technique could still resonate with Lehár's goals. Of this number, Moritz Loeb wrote in the Morgenpost:

Here he is at the peak of his eminent vocal art: victorious and brilliant, he lets loose all his registers; with the most efficient economy of means he can sing the song five times, each time with new phrasing, and the enthusiasm of the audience causes bouquets of flowers to rain en masse onto the stage.Footnote 51

Tauber's technique and sound excused the sameness of the numbers; even his encores had an unusual novelty. Lehár might have professed his work's restraint as a modest offering to the god of German literature, but at this moment Tauber transcended even Goethe. Critic Klaus Pringsheim wrote, ‘But when Tauber had his infallible da capo number in Act II, then his name could have been Goethe or Paganini or Casanova.’Footnote 52 A motif whose first guise is surprising is revealed as the ultimate Schlager pleasure: the journey of ‘O Mädchen, mein Mädchen’ is a synecdoche for the whole of Friederike itself.

Yet Friederike ultimately presents an odd reconciliation between Tauber's excess and its own enforced modesty: the singer and his operetta music are urban interlopers in Friederike's Arcadian world and the plot must expel him. That Tauber's Goethe represents a transgressor is explicitly dramatised in no. 14 ½, ‘Warum has du mich wachgeküßt?!’ (Why did you kiss me awake), a song in which Friederike describes her sexual awakening, with a text alluding to Goethe's poem ‘Erwache, Friederike’. While many of Lehár's heroines would celebrate the number for its pleasure and the discovery would subsequently advance the plot – as it does in Eva, Zigeunerliebe and Der Zarewitsch – Friederike instead sees it as a complication to a still-inevitable separation. She expresses passing hope, but fear and anxious, minor-key regret dominate. Lehár's earlier operettas were dramaturgically premised on opposing social spaces, which would eventually be united, but his late works often reject this resolution. The historical record precludes Friederike fully entering Goethe's world, but the two also seem to be separated by immutable laws of genre, he of the modern operetta and she of the bygone Singspiel. Even as a performance of Friederike represents a fusion of cultural registers, its plot enacts an ultimate separation. The final tableau (no. 19 ¾) finds Goethe famous and successful but Friederike mute, ‘standing steadfastly without looking at him, like a statue of the Madonna dolorosa’.

Song texts

The librettists’ approach to Goethe's poems further reveals a middlebrow agenda. The operetta's song texts mix genuine Goethe poems, sometimes in a quasi-diegetic context (that is, identified as the character's own writing) and sometimes not (integrated into the plot in the fashion of a jukebox musical, a literary equivalent to Dreimäderlhaus). The song texts contain a mixture of genuine Goethe poems and original verse by Löhner; a complete listing can be found in Table 1.

Table 1 Goethe quotations in Friederike. All dates are according to the 1996 edition of the works.

a The fractions suggest that some of these numbers were added or rearranged later in the rehearsal.

b Appears in the Sprüche section of older editions of the works but not in the modern works editions, probably because it is simply a translated quote from Boccaccio's Decameron. See Goethes Sämmtliche Werke: Vollständige Ausgabe in zehn Bänden, vol. 1 (Stuttgart, 1885), 658.

Most of the poems quoted date from Goethe's Sesenheim period (1770–1) – and many are explicitly associated with Friederike – but several are later. Löhner uses, for the most part, short excerpts rather than full texts, often taken out of their original contexts. For example, the operetta's no. 19 ½ (libretto label 19b) quotes the later version of Goethe's well-known ‘An den Mond’. The poem describes the death by suicide of a young woman who drowned in the river outside Goethe's house in Weimar, but it is more closely associated with his relationship with Charlotte von Stein.Footnote 53 In Friederike, it is transmuted into Goethe's warmly sentimental memory of his time with Friederike in Act III. The librettists knew what they were doing, however: they chose not the 1778 original but the more famous second version of the poem, which incorporated elements of a rewritten version sent to Goethe by Charlotte (published in 1789).Footnote 54 While Friederike and Goethe's reunion is an operetta fiction (as the reception frequently noted), the librettists marked the occasion with a poem representing the unexpected reappearance of another of Goethe's lost paramours.Footnote 55

Löhner edited Goethe's language. The Festschrift again notes this departure from history approvingly, claiming ‘one never knows where Goethe stops and Löhner begins. Great praise for him!’Footnote 56 Later, Karl Kraus would present as yet another sign of cultural decay the possibility that some operetta fans would start attributing Goethe's work to Löhner and not recognise it as Goethe (he was so worried about this he put it in Die Fackel twice).Footnote 57 The operetta edits and mixes Goethe's language freely with Löhner's new texts rather than marking it as having a special status – an approach that was essential for presenting Goethe's biography but horrifying for those who wished to preserve a traditional cultural hierarchy. Goethe's language is modernised and simplified, the metre regularised. An example of this is the segment of ‘Nähe des Geliebten’ quoted in Friederike and Goethe's first duet, no. 5b. (The poem dates from 1795 and is a contrafact of another poem by the coincidentally named Friederike Brun.) The operetta uses only the first and part of the second strophe of the four-strophe poem, and then continues with original text:

Goethe's poem maintains the same metre and rhyme scheme for all four strophes. Löhner transforms this into a more typical operetta text by using two contrasting sections, drawing some of the material of the second strophe from Goethe's poem. The image in the first strophe of sun reflecting on a lake is first simplified into direct sunlight from the sky (‘Himmel’ also means heaven); only in the second half of the strophe is water (‘Teiche’) mentioned. The distance is not alienating as in Goethe's very sad poem, but meaningless in the face of an eroticised dream of the beloved's presence.

‘Heidenröslein’, the best known of the Friederike poems, is edited in a different way. For Lehár to set the poem at all was audacious, given the popularity of Franz Schubert's setting (he did not attempt ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’ or ‘Erlkönig’). It is also the only poem where Löhner implicitly trusts that the audience will already be familiar with the text. Herzer and Löhner take this one step further when we witness Goethe write (and sing) the poem towards the end of the first act. The equivalence of music and poetry is acknowledged in the introduction ‘Heimlich klingt in meiner Seele / Eine süß Melodie’, and after a short false start Goethe smoothly writes or composes the first two strophes of the poem. But operetta Goethe only formulates the final strophe, in which the titular rose wilts and dies, at the end of Act II, equating the rose's death with his parting from Friederike (a reading of the poem that is both more specific and more benign than most). The setting integrates one of Goethe's most popular poems into the operetta's imagined history, but in so doing it constrains the poem's meaning, reducing its ambiguity to a simple metonym for a sad and sentimental love story.

On the other hand, however, ‘Heidenröslein’ provides a way of realising a central element of the Viennese operetta formula: the reprise of an earlier number in the second-act finale. Conventionally, this reprisal will arrive with some manner of dramatic reversal. Due to the familiarity of ‘Heidenröslein’, audience members could surely see Friederike's reprise and reversal coming from several numbers earlier. In this manner, Lehár both preserves a convention that he helped popularise and allows audiences the chance to see the formula enacted. The poem is the operetta's dramaturgical accomplice, hardly the ‘simple Singspiel’ and restrained treatment that Lehár and Herzer promised. Even as Lehár frequently referenced ‘higher’ literature, he nonetheless stuck to the formula in important ways.

Everyone was well aware that the plot twist calling Goethe away to Weimar was an invention: the historical Goethe did not make this move until several years later (the BZ am Mittag refers to an ‘artful conflict’).Footnote 59 But the librettists condensed events to create the required dramatic showdown. They also made Goethe's abandonment of Friederike less ethically suspect as he, like Karl-Heinz before him, was called to greatness. The critic of the Vossische Zeitung described this somewhat sceptically as evincing a ‘freedom with psychology’; the much more dissatisfied critic of the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung called this ‘bad psychology’ that made the events ‘coarse’.Footnote 60 Both, in other words, are suspicious not because the librettists have departed from the historical record but because they have been untrue to the nuances of the psychobiography in which the Friederikenliteratur was so invested. This overdetermination – the desire to provide causal, autobiographical explanations for every one of its characters’ actions and its leading character's poems – is a feature of the well-made play; it is also middlebrow. While the real story of Friederike and even the version in Dichtung und Wahrheit are filled with ambivalence and leave many questions unanswered, the operetta ties up all loose ends. It presents the classic poems (or versions of them), shows their composition, and interprets their meaning, all in a familiar, formulaic package.

Genre and Lehár's Weimar image

Ever since Lehár's era-defining operetta Die lustige Witwe had premiered in 1905 he had been one of the unquestioned leaders of the genre. Yet Friederike was an ironic way to celebrate. Much of the production and reception of the operetta focused on questions of genre definition. Was Friederike an operetta or, as its score claimed, a Singspiel? What was Lehár trying to achieve with this novel mix of subject, genre and musical style?

Lehár had long sought and achieved a reputation as an experimentalist. While the results and success of these experiments varied, the most consistent thread was his courting of artistic prestige via the musical tools of the ‘higher’ art of opera, usually opera of a mainstream canonical variety. This meant operettas featuring unusual local colour, heavy orchestrations requiring trained classical voices, and subjects whose serious themes and unhappy endings were unconventional for the genre. In 1912, he explained his aspirations:

I cannot let stand the frequent accusation that I write operatic, tragic and sentimental operettas. The development that modern operetta has taken lies in the developments of the time, of the audience, in all the changing circumstances … My goal is to refine operetta. The audience member should have an experience and not just see and hear nonsense. Through this style I unlocked the court theatres in Germany that play my works alongside Toska [sic] and Tiefland. And as long as my audience doesn't leave me, and my success gives me the privilege, I will continue to work in this style.Footnote 61

Interestingly, Lehár never directly dismisses farcical work, though the connotations are clear enough: he writes works of substance with an eye on history while farce is disposable. Finally, he claims that continued pursuit of this style is validated by public success, a logic that few of the composers he sought as peers would ever have made.

Lehár made similar arguments closer to the premiere of Friederike in 1926, but now updated to reflect interwar theatrical culture. In 1912, Lehár was juxtaposing his style with the Offenbach-style theatrical farce; in 1926 he replaced this with the revue and its montage-like dramaturgy:

The operetta is a genre of art that deals with a human experience in musical and artistic form. So no farce with songs inserted; no more or less meaningless plot that only offers a pretext and an opportunity to put fashionable dances and hits in appropriate and inappropriate places, ubiquitous dances and hits and which could just as well be in any other spot and in any other piece; but no opera either. But of course the popular dogmatic distinction between opera and operetta is taken much too far.Footnote 62

He again defines his work negatively. The revue–operetta never aspired to the standards of the well-made play preferred by Lehár for his librettos. The formal principle is, perhaps counterintuitively, the readily recognisable ‘integration’ of American musical theatre. As historicised by James O'Leary, however, this ‘was never simply a formal principle to begin with. It was a performative act of cultural positioning.’Footnote 63 Integration was and is, O'Leary argues, a vague term, meaning anything from gradual easing into musical numbers to using dance with narrative function to musical numbers that actively develop plot and character to a musical idiom or colour suited to the subject. O'Leary's primary subject is Oklahoma!; he argues that director Rouben Mamoulian and sympathetic critics associated integration with opera in order to claim Oklahoma! as more highbrow than its peers. Yet, in its specifically aspirational character, Oklahoma!, like Friederike, ends up in the zone of the middlebrow.

Lehár makes a very similar argument several decades earlier: an integrated operetta approaches the realm of opera and elevates it from the zone of low culture. But while Oklahoma! has been served well by its association with integration, the circumstances in Weimar Berlin were different. In 1927, musicologist Alfred Rosenzweig described the aesthetic of the ‘revue technique in opera and operetta’ in terms redolent of modernity:

An audience whose nerves are tuned to the mass uproar of the sports arena, the buzzing furioso of the film and the electrifying hammering of jazz rhythms, for clear, unambiguous, well-defined and obvious effects. The renaissance of bodily sensation, the physicality, the surge in gymnastics and dance have also greatly contributed to the amplification of the visual, the scenic dynamic.Footnote 64

As indicated by his title, Rosenzweig has already grasped the closing of the Great Divide: the revue technique he defines, whose sensory overstimulation and bodily liveness typifies so much of what is conventionally associated with Weimar art, is found not only in the low art of the revue but in the works of Paul Hindemith and Egon Wellesz. (Almost in passing, he describes the ‘failure’ of operetta's traditional three-act structures, without much elaboration.Footnote 65) Lehár would never gain approval from the modernist critics who would seem to guard the gates of highbrow culture. A binary view of high and low culture would therefore judge his Friederike project a failure on Lehár's own terms – as does Carl Dahlhaus in his dismissal of Friederike as ‘a pseudomorphic hybrid foredoomed to artistic failure’.Footnote 66 Yet Lehár realised very well that he was not Hindemith and would never be taken as such; his repeated attempts to set himself apart from the world of modernist culture and define his terms according to canonical values rather than those of innovation exemplify a middlebrow approach.

Ernst Bloch saw Friederike as a failure of the newspaper critics rather than of Lehár: ‘For the highest aims, the strictest artistic practice, these parasites had nothing but subjectivistic insolence, for the new Mozart, Lehár, they displayed the appreciation of dealers in stolen goods.’Footnote 67 He quotes a number of those critics, who he views as mistakenly seeing Lehár's work as legitimate rather than ridiculous. This recalls the duplicity Chowrimootoo identifies as characteristic of modernist critics of the middlebrow: the middlebrow artist ‘undermined modernist investment in aesthetic hierarchy and purity even as it stole audiences from modernism proper’ (in this case, audiences might be column inches).Footnote 68 Operetta, Bloch went on to say, should serve a satirical function, not a sentimental one – the universal refrain among intellectual critiques of operetta from Kraus to Klotz.Footnote 69 But Bloch is on some level correct: the critics took Lehár seriously. With them, at least, Lehár had won.

Lehár's proclamations also illustrate how he stood apart from most of his colleagues in operetta, a condition that had grown only more pronounced by 1928. While in 1905 he had often been seen as an exemplar of modernity (as Felix Salten famously wrote in 1906Footnote 70), by 1928 neither he nor anyone else was making that claim. While Lehár continued to pursue his operatic tendencies, most operetta composers were aping the modern forms of the revue described by Rosenzweig by the time of the premiere of Friederike (the enormously popular collaboration with Tauber).Footnote 71 As Oscar Bie wrote in his Berliner Börsen-Courier review, ‘Lehár has, of course, kept far from all modernism and any jazzing [Jazzerei].’Footnote 72 Lehár was after something different: a conservative style that he argued connoted classic status, prestige and respect. This is what he sought through Friederike's engagement with Germanic cultural icons.

While Lehár's Berlin years were fabulously remunerative, he claimed that his style was less beholden to the market than that of his fashionable colleagues. In the 1926 Feuilleton, he wrote that modern operettas sought only the ‘Serienerfolg’, that is, a long-running show that settled into a theatre for a year or more (an antecedent of the megamusical):

The goal is the big one-time series success, not the creation of a work of art; the business interests dominate, one can say: as a rule they are the only things still standing. The purely materialistic tendency of operetta makers has taken away operetta's soul. All one is looking for is new sensations, jokes, drastic situation comedy, unusual dances and acrobatic tricks – and the music goes the same way, in its own way. But I think that in operetta the connection with the human must never be lost … That is the secret of an appeal which is directed to the emotions and which is deeper, purer, and more genuine than that of a mere show.Footnote 73

Lehár's quintessentially bourgeois conception of art – which claims to reject the market (while still fully participating in it) and nominally rejects the flashier or more provocative elements of Weimar culture by being a mere ‘small Singspiel’ – demonstrates how he consciously worked against the critical grain of his own day to create an image of himself as an exemplar of a new canon of classics. By aligning the market with an aesthetic rather than a practice, he was able to claim he had left it without giving up any profits.

Lehár went to special lengths to claim Friederike as a personal project, casting himself in the role of the Romantic artist (in implicit parallel to the operetta's subject). He would later speak of the score with a sense of personal investment; according to a 1927 interviewer, ‘he calls the work his “most interior interiority”, dedicated with deepest feeling and total devotion’.Footnote 74 The nature of that interiority is worth considering: while Lehár was one of the most prominent exponents of transnational operetta, famous for his Slavic-toned Die lustige Witwe and his popular songs, the sincere interiority revealed by Friederike was a composer beholden to Mozart and Schubert.Footnote 75 As the BZ am Mittag put it, ‘There is nothing of the earlier Lehár in this music … He is – one can hardly believe it – in this score completely German; folk songs and German dances are the guiding stars that lead him.’Footnote 76

Many critics also commented on the work's designation as a Singspiel, a choice which aligned it with Die Zauberflöte and not Die lustige Witwe. For some, that also distanced it from the commercial:

In its musical approach, the work is much more a light opera than an operetta in the usual sense.Footnote 77

Lehar's curiosity in his compositions always showed a curiosity towards light opera, but on the whole he has hit the style of the Singspiel wonderfully and carried it consistently almost throughout.Footnote 78

Erich Urban was more sceptical. He ultimately concluded that Lehár possessed a musical ability that could transcend the categories he nevertheless valorised:

Franz Lehár set this Singspiel to music with a palpable longing for opera. He wants to make serious music; but this undertaking is again beyond his strength; and when in the second act he lets Friederike sing a sad song with Hungarian phrases, he obviously doesn't know how fake it is. But he is real in the folk-like, light melodies, also in the light and formally often charming orchestration, he is real in, let's say: ‘Goethe-Walzer’, in the hit song ‘Mädchen, mein Mädchen’ and in many similar things. But all of these pieces are genuine operetta, and it doesn't change the fact that the sure hand of the sensitive, skilled musician can often be felt in his well-chosen idioms.Footnote 79

No other critics found Friederike's no. 14 ½ (described above) out of place or Hungarian, but Urban shows the scepticism regarding Lehár's ability to fully convince in a serious historical setting or in what he (Urban) considered more serious genres of music. Klaus Pringsheim of Vorwärts put it similarly: ‘there is something touching about its diligence: every prop, every wig is picture perfect for the Goethe age, but the foundation, the atmosphere is still operetta. Even if it doesn't want to be one.’Footnote 80 (This idea of diligence was echoed by Brooks Atkinson in the first line of his Broadway review: ‘Everything has been properly attended to in Frederika.’Footnote 81) Following the Viennese premiere, the more satisfied Ludwig Hirschfeld wrote, ‘Lehár is withdrawing more and more from mere light music, more and more his ambition is to strive for serious, nobler goals: operetta on the level of opera as a pure work of art, not composed for the moment but for eternity, or at least for music history.’Footnote 82 These critics fell reflexively into the binary discourse of serious and light music, yet for many of them the operetta was disturbing, failing to conform fully to either because of its internal inconsistencies or the lack of congruence between its aesthetic goals and its production venue. While these divergences have frequently been judged as a failure on the part of Lehár, it is more interesting to read Friederike's reception as a failure of the labels to describe what was happening.

The more positive reviews tended to emphasise the work's craftmanship. Particularly at a moment when popular music was characterised as mechanical or mass-produced, this emphasis on handiwork and refinement is striking. Karl Westermeyer wrote that, ‘the most astonishing thing is Lehár's music. We knew that a cultivated musician like him would not fail in the face of this extremely difficult subject. But he surprises us with a new stage of development.’Footnote 83 Historian Bernard Grun adopted Lehár's language and described Friederike as ‘stylistically authentic, [possessing] sensitive beauty … noble orchestration and masterly economy’.Footnote 84

In comparison, Ernst Bloch noted this tendency in reception and compared Friederike's rectitude unfavourably with Lehár's less prim early work. Critics, Bloch accurately noted, constantly expressed ‘vaunted astonishment at his [Lehár's] “beneficial restraint” … the young attaché Danilo in Die lustige Witwe didn't need to be decent’.Footnote 85 For Bloch, such newfound restraint was bourgeois, the marker of an operetta that was less daring and unexpected than the composer's previous efforts (the comparison with earlier Lehár is unusual; most writers would name Offenbach). The Festschrift cast this same change in a far more positive light: ‘The operetta has long since been legitimate, not an outlaw, not something at which the Bürger will turn up his nose. The operetta itself has become something bourgeois, something that belongs to the law, to the government, to society, to the governing council, to the director of the men's singing society.’Footnote 86 Squeezing between the converging paths of the revue and high modernity, Lehár found a new home for his old style.

Friederike as emblem of operetta

Friederike was, as the critics predicted, a healthy commercial success, eventually surpassing its contemporary Dreigroschenoper in audience numbers. But it then faded quickly. Throughout the Third Reich, Lehár was the most performed operetta composer in Germany, the names of his Jewish librettists simply excised from programmes. Yet Friederike, as a Jewish-penned image of German culture, was performed only very occasionally and very quietly; until Stefan Frey's recent work it was often described as banned. As Frey has shown, Friederike almost disqualified Lehár from the Goethe Prize until a private performance earned a lukewarm endorsement from Josef Goebbels as ‘not tactless’ in its treatment of its subject.Footnote 87

Across the sea, Jewish librettist in exile Alfred Grünwald wrote a history of operetta, which is still unpublished. He saw Friederike's success as a symptom of a larger cultural malaise: ‘The Weimar Republic, sick to its deepest roots, was no more resistant against the demolition of this or that tradition. So as later Hitler was greeted and eventually endured, so they also endured the Brüder Rotter [the producers at the Metropol-Theater] and the small, harmless offering of the theatre.’Footnote 88 The comparison of two Jewish theatrical producers – exiles like Grünwald – with Hitler is dubious or worse, but tracks with larger Weimar narratives that have tended to see the roots of political disaster in cultural nonconformity (nonconformities that would mean death only a few years later). Grünwald could not have known that the Nazis were also wary of Friederike. Without the very special and labour-intensive circumstances of its premiere – Lehár's publicity tour, Tauber's celebrity, the cooperative reception and the ability to see it in relief against the rest of 1928 Berlin – traditional hierarchies of high and low were reasserted and Friederike became illegible, not fit for anywhere at all.

Operetta scholarship has long followed the puritanical footsteps of early critics. Volker Klotz's monumental Operette: Porträt und Handbuch einer unerhörten Kunst (revised in 2004) moves to differentiate between ‘good operettas and bad ones’ in a section with that title on its second page of full text. For Klotz, good operettas possess ‘rebellious centrifugal forces’. However, he continues,

Bad operettas are those which have suffocated the fundamental impulse of their genre. They have taken back the ironic and self-ironic ludic drive, the satirical aggressiveness, and the anarchic law-breaking in favour of mass appeal. The petit bourgeois audience, rather than being enticed outside their self-imposed boundaries, transfigures every false pleasure into bright colours and sounds.Footnote 89

Klotz's hall of dishonour includes Der Zarewitsch, Friederike's predecessor in Lehár's œuvre, along with works central to operetta repertories and historical development such as Johann Strauss II's Der Zigeunerbaron – works he argues that ‘have entirely left the scope of operetta’. But Klotz's definition is prescriptive, not descriptive, and points to a longstanding gap in operetta studies between its audiences and those who have studied it. Critics from Bloch to Klotz have usually found operetta not to live up to an idealised image of Offenbachian satire, while audiences have, for the most part, flocked to performances of Zigeunerbaron and Friederike and showed less interest in Klotz's predecessors. The historiography which has resulted lacks the analytical tools to cope with Friederike and other ‘bad operettas’ – which, as Klotz despairs, comprise much of the genre's output.

Klotz's words recall those of Rosenzweig quoted above. Like Lehár himself, operetta historians have sought prestige; unlike Lehár they have more often sought it in Rosenzweig's sexy revue and the meeting of high and low cultures, rather than in Lehár's salvo at Viennese classicism. Recent revivals of Berlin-era revue–operettas by the Komische Oper Berlin under the direction of Barrie Kosky have attempted to define the image of operetta as a genre in touch with modernity, often defined against the fustier performance traditions of specialist operetta festivals, TV films and regional opera houses.Footnote 90 This has not, however, extended to late Lehár, a repertoire conspicuously absent from Kosky's revivals (this is particularly notable because the Komische Oper now occupies the former Metropol-Theater, where Friederike premiered). Musicologist Kevin Clarke, a fan of Kosky's work, has argued that the traditionalist approach is a Third Reich and post-war phenomenon, and locates it in Nazi attitudes towards jazz and subsequent West German TV and radio broadcasts. In so doing, he casts a strong moral valence on this argument, equating jazzier operettas with liberatory Weimar and Jews and middlebrow aesthetics with the Nazis, which he also casts in unambiguous aesthetic light: ‘Could one free [operetta] from a performance practice that gave the genre the worst image imaginable after World War II?’Footnote 91

Yet operetta's turn towards the middle is not a post-war phenomenon and, equally importantly, the conversation about these performance traditions has changed surprisingly little since 1928. Moreover, Friederike was the creation of two Jewish librettists (one of whom, Löhner, was murdered in AuschwitzFootnote 92). Even more than Klotz, Clarke presents a rhetorically powerful argument, offering both a political and an aesthetic critique. But as a historical argument, it fails to account for the diversity and complexity of Weimar culture, or for the internal debates within operetta during the pre-war period. The middlebrow, in its very broadness, refuses to be reduced to a simple moral or political binary. Since well before 1928, the voices who have written about operetta have too often preferred a vision of operetta at odds with operetta as practised. From the start, Lehár, the librettists and many critics sought to distance Friederike from operetta traditions. But what if its reception, and ultimately the work's own ambivalence, are in fact exemplary of much German-language operetta history? What if not just late Lehár but much of German-language operetta was always middlebrow? This would mean spending more time with repertoires that have been dismissed as abject and recognising the generative potential these very critical conversations have had on operetta composers and librettists. For both Weimar histories and operetta, a closer look at works like Friederike can reveal a musical world in flux, where categories were reified even as they were transgressed.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at the ‘Music and the Middlebrow’ Conference at the University of Notre Dame's London Global Gateway, June 2017. I am grateful to the conference participants for their helpful feedback as well as the anonymous reviewers from this journal.