The fury and violence had given way to calmness and peace … the results with CPZ could be measured in the psychiatric hospital in decibels… recorded before and after the drug.

Jean Delay (cited in Sherman, Reference Sherman and Sherman2016)

Humour is not resigned; it is rebellious. It signifies not only the triumph of the ego but also of the pleasure principle, which is able here to assert itself against the unkindness of the real circumstances.

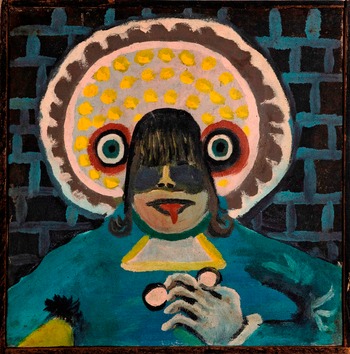

A curious painting, produced by an anonymous patient hospitalised at the Miguel Bombarda Psychiatric Hospital (1848–2012) in Lisbon in the early sixties, recently caught my attention (See Fig. 1). The plastic refinement of the work – a small quadrangular oil on wood panel – with the title Largactil Tablets [Os Comprimidos de Largactil] and the accompanying text in small font, make it into a typical example of art brut produced by people living in a psychiatric asylum. The painting and text introduce us to the subject's personal ‘psychiatric experience’. In both painting and text, the author depicts an essential moment of the hospital routine: taking medication. In addition, through its title, the painting unwittingly reminds us of the ‘revolution’ that took place in 20th century psychiatry, in part due to the discovery of chlorpromazine (CPZ). This chemical substance was discovered by the French Naval surgeon and physiologist Henri Laborit (1914–1995) during his research on so-called ‘artificial hibernation’ in the prevention of surgical shock. CPZ was soon applied by psychiatrists as a general sedative and marked the ‘beginning of the end’ of asylums and the decrease in the number of those admitted to mental institutions (Lieberman, Reference Lieberman2015; Sherman, Reference Sherman and Sherman2016).

Fig. 1. Largactil tablets [Os Comprimidos de Largactil]. Oil on wood panel, 35, 5 cm × 35,5 cm, date 1963. Copyright: Private collection.

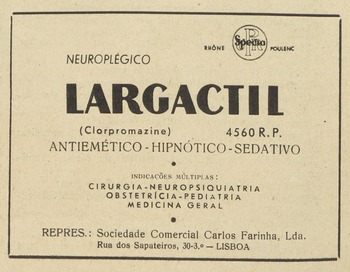

Chlorpromazine has given new impetus to treatments in the field of mental health care (Pieters and Majerus, Reference Pieters and Majerus2011; Sherman, Reference Sherman and Sherman2016). Before the use of this neuroleptic and drugs such as imipramine and lithium, serious mental illness condemned the patients to a lifetime of confinement and reduced activity. Chlorpromazine was distributed in Europe by the pharmaceutical company Rhône Poulenc under the trade name of Largactil – the acronym for Large Action. In the United States, it took on the name of Thorazine. In Portugal, the first reference to the use of this neuroleptic appears in an article published in 1955 by the psychiatrists Mendes and Galvão. At the same time, advertisements for the drug appeared on the pages of the prestigious national Jornal do Médico (Mendes and Galvão, Reference Mendes and Galvão1955; Santos, Reference Santos2019) (See Fig. 2). Mendes and Galvão emphasised that the administration of the drug was useful in the treatment of schizophrenia because of its calming effect that facilitated the introduction of the ergotherapeutic activities with which the main Portuguese psychiatric hospitals were experimenting at the time.

Fig. 2. Largactil advertising, in Jornal do Médico, XXIII, 587, 1957, p.1042.

Other psychiatrists, however, claimed that patients treated with CPZ behaved as if they had been chemically lobotomised (Pieters and Majerus, Reference Pieters and Majerus2011). This analogy to lobotomy lost force when it became clear that patients who had been hospitalised for years with chronic psychiatric conditions opened up to communication with others and became successfully involved in the therapeutic and other activities promoted by hospitals. The new drug acted to improve the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It was first introduced in a psychiatric environment, namely the prestigious Saint-Anne Hospital in Paris, by Jean Delay (1907–1987) and Paul Deniker (1917–1998). Soon chlorpromazine became the most prescribed neuroleptic in the sixties and seventies in both Europe and the United States of America.

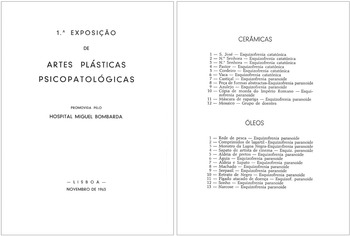

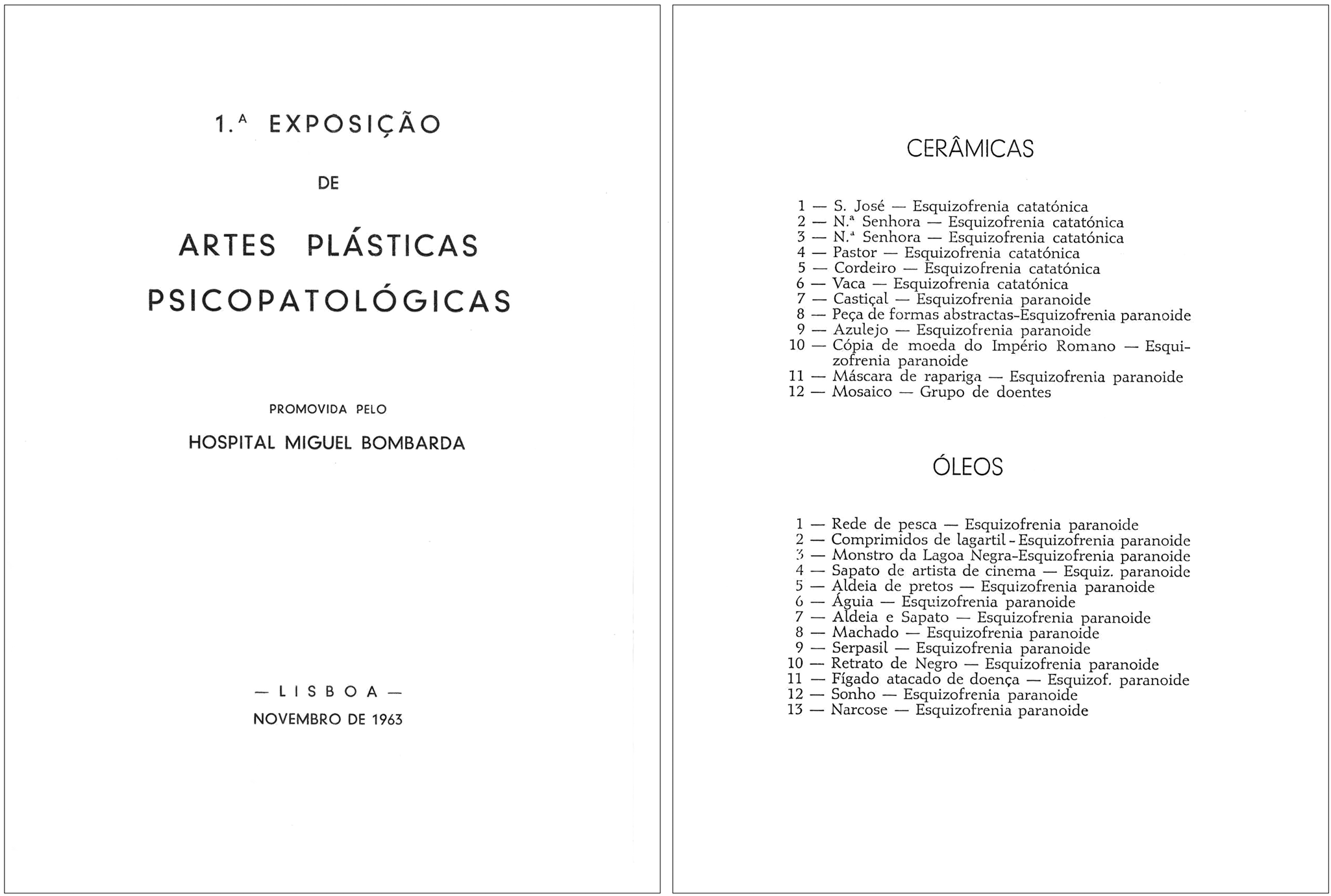

The painting Largactil Tablets was identified by me in the brochure of the First Exhibition of Psychopathological Arts that took place at the Miguel Bombarda Psychiatric Hospital in 1963 (See Fig. 3). In the booklet, the title of the work is associated with the nosological entity attributed to the painting's author: paranoid schizophrenia. The organisers of the exhibition wrote: ‘the works on display are freely performed by our patients in an occupational therapy regime. The aim of our exhibition is to show the public that the mentally ill person is not a prototype of human ruin as is generally thought, but an individual capable of making a creative effort.’ One hundred and two works were exhibited, part of which were preserved in the hospital's artistic collection while others were sold during the exhibition.

Fig. 3. Excerpt from the brochure of the First Psychopathological Arts Exhibition at the Miguel Bombarda Psychiatric Hospital (Lisbon). In the section Óleos (Oils) the title of the artwork # 2 is Largactil tablets [Os Comprimidos de Largactil] with the assigned clinical diagnosis ‘paranoid schizophrenia’. Copyright: Biblioteca do Centro Hospitalar Psiquiátrico de Lisboa.

Somehow, at the Miguel Bombarda Hospital, several collaborators, psychiatrists, and occupational therapists followed what was theorised in France by Dr Robert Volmat (1920–1998) in the late 1950s. Volmat's book, L'art psychopathologique (Reference Volmat1956) was the result of the exhibition organised during the First World Congress of Psychiatry at the Sainte-Anne Hospital in 1950, where 2000 works were shown. This book served as a source of inspiration for studies carried out all over the world in the 1960s and 1970s. Volmat's use of the expression ‘psychopathological art’ at the time certainly didn't have the stigmatising flavour it has now. The work of this psychiatrist and his colleagues led to the development of art collections and to the promotion of artistic creation by patients, whose products were considered as ‘laboratory material’ for study.

Thus, the systematic experimental study of the drawings and paintings of the mentally ill began after 1950. Previously, the plastic productions that were found in the wards appeared spontaneously and only some of them were preserved. From the 1950s onwards, in several psychiatric hospitals, selected patients were taken to an appropriate room and asked to paint whatever they wanted. Due to the influence of psychoanalysis, no theme was suggested at the time or the copying of models was promoted. Over the years, a transition took place in the thinking about the therapeutic use of drawing and painting. For Volmat and his colleagues, the approach to ‘psychopathological art’ rested upon three points of view: clinical, psychopathological and therapeutic. Thus, the interpretation of works of plastic expression by the mentally ill was promoted to a scientific category based on ideas borrowed from Gestalt psychology, phenomenology and psychoanalysis.

In Portugal, the interest in the spontaneous artistic productions of ‘mad’ persons saw the light at the turn of the 19th century to the 20th century, through the efforts of the Portuguese doctor, writer, and literary critic Júlio Dantas (1876–1962). His undergraduate thesis as a clinician, entitled Painters and poets of Rilhafoles [Pintores e poetas de Rilhafoles] (Reference Dantas1900) (Rilhafoles /Miguel Bombarda Hospital) at the Lisbon Medical-Surgical School (Escola Médico-Cirúrgica), proved to be a pioneering work in the European context. Dantas's work was supervised by the father figure of Portuguese psychiatry, Miguel Bombarda (1851–1910), the alienist who used artworks and poetic writings made by patients in the First Free Course of Psychiatry in the country (1896). Bombarda wrote a short article entitled Art and Asylums (Arte e Manicómios) (Reference Bombarda1900).

Miguel Bombarda, a republican and anti-clerical activist, was shot dead in his office by one of his patients, a monarchist officer, shortly before the establishment of the Republic in Portugal in 1910. Over decades, the spontaneous work of patients was collected at the Bombarda Hospital. Today – what was left of that hospital closed in 2012 – a few thousand works still remain to be studied and classified. For the alienists Miguel Bombarda or Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), the works of the ‘crazy’ were devoid of artistic merit. Its value would be acceptable if the works served as a complement to the diagnosis of mental disorder and constituted tools for the education of art critics.

The painting I show here was made at a time, starting in the 1950s, when the so-called ‘psychopathological art’ tradition was still active in France (Dubois, Reference Dubois2019) and Portugal (Pereira, Reference Pereira1963). This approach to the patients' productions emanated from the idea that the written, verbal and pictorial expression of patients directly reflected the proposed classification of their mental illnesses: their works did not belong to the world of art but were symptomatic for their disease. Thus, the plastic works produced, like the one I show here, were treated as documents and not as works of art (Dubois, Reference Dubois2019).

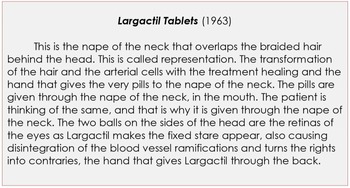

The person who painted Largactil Tablets produced one more painting with the same format and style. The other painting depicts a naked nurse with electroshock devices in her hands. Both paintings were acquired during the First Exhibition of Psychopathological Arts in 1963 mentioned above. I have not identified the sex or name of the person who made them (although I suspect the patient was male), nor have I found any supplementary data about the patient's life or the reasons that led to the psychiatric hospitalisation. What is particularly remarkable is that the painting is accompanied by a description of the painting by its author that was recorded by a nurse at the Hospital (See Fig. 4). In these two documents, painting and text, a subtle ‘criticism’ of psychiatry, of its power over others, appears. This ‘criticism’ arises from the expression of humour, from the pleasure that the use and relief of tension allow the subject when he expresses himself both verbally and pictographically about a drug he knows by name and whose effect he experienced himself.

Fig. 4. Transcription typed by a hospital nurse of the verbal interpretation of the painting by its author. Translation from Portuguese. Copyright: Private collection.

Freud (Reference Freud and Richards1928/1990) wrote that the humorous attitude can be directed at oneself or at others. This type of attitude provides pleasure and freedom to whoever is at its origin, transforming itself into a similar gain for the spectator who participates in the ‘scene’. Humour can be the projection of contained ‘aggression’ that results from the impotence of the subject who feels forced to change the situation or finds himself harassed by a dominant system from which he cannot defend himself in any other way. This may be comparable to what happens to those who are dependent on clinical treatments, often in psychiatric confinement.

In my interpretation, this painting and text illustrate its author's lived and projected mood and emotional tension. The background of the painting suggests a wall organised in small squares, possibly bricks. It could be an allusion to the confinement in the asylum. It is a rational painting, elaborate in its details, made with a brush with oil paint. In the foreground, a female figure comes up, it could be a nurse: the person with the authority to perform the medication administration routine and chosen by the ‘artist’ for the revelation of his irony. The figure's hair is done with bangs and a red tongue appears from her mouth. Underneath the chin, a white triangular configuration appears with a yellow contour line, perhaps the neckline of the figure's bluish dress. The figure holds in her left hand two white circular objects, presumably a representation of Largactil pills. The details of the hand are impressive: the contours of the hand are depicted with great precision. Not only this detail, but the painting as a whole, clearly reveals the artist's artistic talent. The accompanying text is a concise description of taking the drug and its effects (See Fig. 4).

As if it were a surreptitious act, the hand gives the Largactil pills ‘behind the neck’, i.e., not directly. The nape of the neck may be the metaphor referring to the painter himself. At the back of the head, two other, concentric circular shapes appear: a luminous circle, inside dotted in yellow. The attention of the observer is first drawn to the halo, which has a kind of ‘hypnotic effect,’ then to the figure's face. Two inner circles, which he calls ‘balls', are one on the left side and the right side of the head. The patient writes that they are the ‘retinas’ of the eyes and that Largactil makes ‘the fixed gaze appear’. Perhaps the effect of the medication accentuates the focus of the gaze. They are large eyes, ‘retinas’, which observe what is happening around them and which also ‘look inside’ the subject. Perhaps this is a paradoxical effect of the transformation from one mental state to another through what it the text says is the ‘disintegration of blood ramifications' and the ‘transformation of rights into contraries’.

Thus, in this painting I find two dimensions that are relevant to our understanding: the aesthetic quality of what was imagined and the narration that informs about the experience of the individual with mental illness. The main actor of this story, without knowing it, became a subject who participated in the paradigm shift in psychiatry in the 20th century: the introduction of antipsychotic drugs, which caused a rupture with the previous ‘treatments’. For sure, the anonymous author could not imagine that his painting and text would be rediscovered six decades after later and would become a topic of the discussion about the art produced in psychiatric hospitals in the 20th century.

Acknowledgements

The author is especially grateful to Lurdes Barata, librarian of the Medical School of Lisbon Unversity as well as to the National Library of Portugal for the documentation supplied. Thanks are also due to Clara Paulino for the translation of the artist's description of his artwork and to the painting's owner for the permission to reproduce the painting in this article. Finally, I would like to thank René van der Veer for his comments on a first draft of this article.

Financial Support

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

About the author

João Pedro Fróis is a University Professor and Researcher. His main interests lie in the Psychology of Visual Arts, Empirical Aesthetics, and the Philosophy and History of Art Education. He has published articles in several journals on the psychology of the visual arts. He has worked as a Rehabilitation Psychologist for more than a decade. As from 2014, he has been a Fellow of the International Association of Empirical Aesthetics. Research Associate of the Center for Phenomenological Psychology and Aesthetics – CPPA, Department of Psychology, University of Copenhagen. Senior Researcher, Faculdade de Medicina – Universidade de Lisboa.

Carole Tansella, Section Editor