The Potosí silver mines are said to have been present at the birth of global trade, which began to grow in the sixteenth century. The mines continued to be exploited until the first few decades of the nineteenth century.Footnote 1 Throughout that long period, the mines were worked by the indigenous population, most particularly under the system of mita or unfree work, which was established in the final decades of the sixteenth century and remained in place until it was abolished in 1812.Footnote 2 Behind the continuity of the mita lay important changes that will be examined in this article. It will look, too, at other forms of work, both free and self-employed. The analysis is focused on how the “polity” could shape labour relations, especially from the end of the seventeenth century (1680) and throughout the eighteenth century. The role of the state as conqueror in early times, as employer more recently, and as redistributor over the past few centuries has been pointed out by the editors of this Special Issue. This article scrutinizes both the labour policies of the Spanish monarchy, which favoured certain economic sectors and regions to ensure revenue and the initiatives of mine entrepreneurs and workers, who contributed to changing the system of labour.

My point of departure was to think about the complexities of what the “state” is.Footnote 3 In contrast to the concept of a well-defined and identified institution, over the past decade academics have criticized the notion of a geographical and political centre of power conceived as one entity with a single coherent policy, and any clear distinction between the state and civil society. The approach taken here is to consider the state as an ensemble of political and administrative levels interconnected through policies and practices. Those policies and practices are conceived of as the result of conflicts and struggles between different actors, groups, and regions, generating a dynamic with often unpredictable consequences.

The first part of this article summarizes my view of the main labour relations and their shifts over four periods from 1545 to 1812. After an initial period of exploitation, based mainly on a system of sharecropping, mita or unfree labour was established in 1574–1575 during the second period and coexisted with free minga labour. Through the years, mita changed along with the whole labour system, and I shall describe its main characteristics and shifts. With this panorama, which complements the contribution by Raquel Gil Montero and Paula Zagalsky in the present Special Issue, this article focuses on the struggles to widen or abolish mita unleashed almost a hundred years after its implementation (1680–1732). Here, my analysis centres on the interaction between the authorities at different levels within the Spanish monarchy.

The second part of the article draws on the debates that took place within the different levels of the state, while the third examines workers’ initiatives in response to developments in state policy that influenced the entirety of labour relations. In the eighteenth century, self-employed workers or kajchas emerged and consolidated their position in close association with rudimentary ore-grinding mills, called trapiches, where silver was refined. The peculiarity of the eighteenth century lies in the fact that the main sources reveal that both unfree mitayos and free mingas could have been the same self-employed workers. That means that workers’ control over production and processing was growing, and explains why coerced labour could not be transformed either into completely free labour, or into completely unfree labour. The result was a combination of different settings in which labour fell into distinct categories, but this did not mean that there were necessarily always distinct groups of workers.

Finally, in the fourth part, I shall analyse a new wave of discussion dealing with the right of the Crown to favour the Potosí mines and their tenants as if they formed part of the state public sector. That was a significant debate and should be placed in the general context of the projects and reforms of the monarchy in the eighteenth century and changes in the political process from 1808–1812 that led to the disintegration of the Spanish Empire.Footnote 4 The debate involved functionaries in different administrative and political layers of the economic and political establishment. As we shall see in more detail in the last part of this article, this included the mine owners and mercury millers (azogueros) of Potosí, the authorities in the cities, and the judicial and religious authorities of the Audiencia de Charcas (see Figures 2 and 3). One of the highest authorities of the audiencia questioned the general assumption that silver was the “blood of the political body”.Footnote 5 The discussion undermined the legitimacy not only of the authorities, but also of the mita, because it was a burning issue over a large geographical area and had consequences for the next twenty years until its formal abolition in 1812 in the Cortes de Cádiz that gave Spain its first constitution. In the process, the mita became a symbol of inequality, oppression, and of a system of labour associated with the ancien régime and the conquest of America.

SILVER PRODUCTION AND THE MAIN SHIFTS IN LABOUR RELATIONSHIPS IN POTOSÍ, 1545–1812

The Potosí mines were “discovered” in 1545 and very quickly began to be exploited for the benefit of the Spanish Crown. Legislation maintained the legal doctrine of royal ownership of the subsoil, allowing it to be exploited by individuals in exchange for a tax on what they produced. In principle, the king granted rights to his vassals and subjects, whatever their status. However, with some exceptions, the indigenous people did not own the seams of Potosí’s mines and became workers.Footnote 6

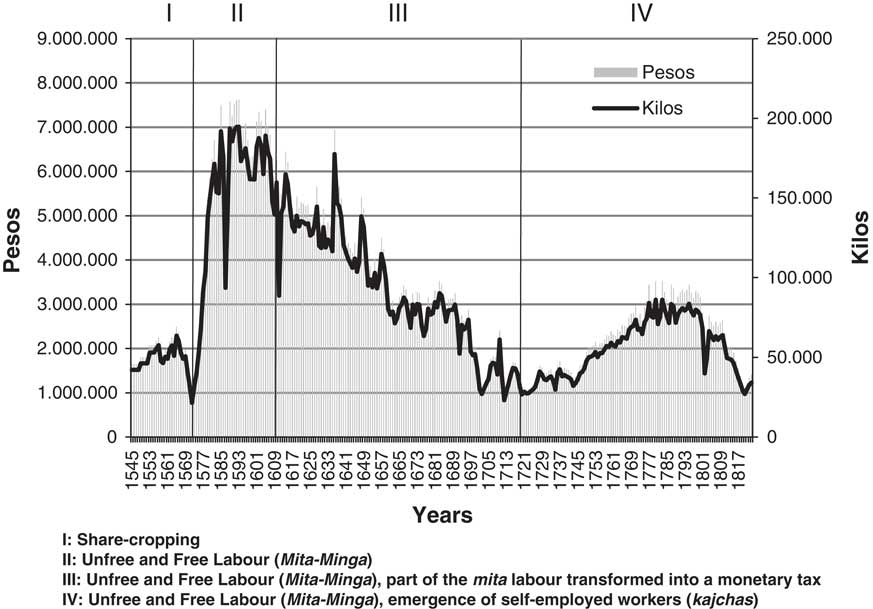

Production figures for Potosí (Figure 1), as reconstructed by Garner and TePaskeFootnote 7 and based on the royal tax levied on the production of silver pesos,Footnote 8 shows a spectacular boom between 1549 and 1605, a decline during the seventeenth century, and then recovery between 1724 and 1790.Footnote 9 As we shall see, those trends are related mainly to the richness of the ores and to labour policies.

Figure 1 Silver production in Potosí (1545–1817) and the main forms of labour relations Source: Garner Peru sheets, based on TePaske, available at www.insidemydesk.com. The labour relations have been added by me. The vertical axis to the left gives the value of silver in pesos. See footnotes 7, 8, and 9.

In terms of labour relationships, I distinguish four periods. The first runs from the Spanish discovery of the mines until 1573–1575. Then, Viceroy Francisco de Toledo instituted the mita system, which began the second period, when Potosí reached its apogee. The third of these periods runs from 1610 to 1720, when production decreased for many reasons, chief among which were the impoverishment of the ores and a shortage of labour. Over those one hundred years the mita system “metamorphosed”, with corvée labour changing to cash payments as production declined. Finally, the fourth period was marked by a renaissance in the production of silver in Potosí after 1720. Although that rise in production appears small in comparison with the first, it was, nevertheless, important. Output of silver rose, partly because in 1736 the tax on silver was reduced from a fifth to a tenth of its value, but also because of the additional mercury supplied from AlmadenFootnote 10 and as a result of a consolidation of the activities of self-employed workers, or kajchas.

Let us analyse this overview in more detail. In the first period, the extraction process, smelting, and casting in wind-blown furnaces (a traditional pre-Hispanic technique called huayras), and the sale of the silver in local markets were all controlled by the indigenous population. They carried out the extraction using their own means of production, exploiting part of the mines at their own cost and largely for their own benefit. It was a system of sharecropping, or a kind of leasing of property.Footnote 11

Figure 1 shows an astonishing increase in production after 1575. The period was marked by the rule of Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, who, in the 1570s, organized the “colonial system”,Footnote 12 which involved re-launching mining from Potosí (due to the scarcity of high-grade metals), introducing technological changes and the mita as a method of continuous provision of labour. The amalgamation process, in which pulverized ore was blended with mercury, required the provision of mercury from the Huancavelica mine in Peru, water for the refining mills, and an important contingent of manpower – through the mita system.

The institution consisted of a constant supply of labour based on the pre-Hispanic system of work, the mita, meaning “turn”. Toledo organized the system, which involved an Indian labour force of 14,000 men between eighteen and fifty years of age being recruited from seventeen provinces to work in Potosí, taking their families with them. They worked in Potosí’s mines and mills for a year under the leadership of local Indian authorities (caciques, or curacas).

The mita workers (draft labour) were therefore one part of Potosí’s labour system, while the minga workers made up the rest. Insofar as the mita were considered unfree labour, the mingas can be considered free labour. However, my recent research has led me to conclude that instead of two separate and opposed categories, we should think in terms of a single system of work, the mita-minga system, which I found applies particularly to the eighteenth century. To understand that, we must remember that every year the total number of mitayo or unfree workers was divided into three contingents of labourers. The contingent not working were considered to be in “huelga”, or “on strike”, indicating that they were effectively on leave. Turns of work alternated each week so that, in principle, everyone worked for one week and “rested” (in “huelga”) for two weeks. The mitayos then had to work seventeen weeks or four non-consecutive months, which they did throughout the year. Some sources indicate that the free workers, or mingas, were recruited precisely from among men who were “de huelga”, in other words the mitayos.Footnote 13 If that was so, then the mingas were, on the whole, the same people as the mitayos.

Mitayos (corvée, or unfree workers) and minga workers (paid by the day, or free workers) were present from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, but the continuity of terms for workers can obscure changes that began in the first few decades of the seventeenth century, when some workers avoided unfree mita work by transforming their obligation to work into a payment in cash, a process generally channelled through their authorities (caciques). During that third period, what Cole has called a metamorphosis of the mita took place.Footnote 14 The money paid by the workers through their own native authorities could be used by the mine and mill owners to employ free labour or minga workers, but in some cases they simply kept it for themselves.

During the seventeenth century, an enormous amount of regional migration occurred as people from communities obliged to send mita workers decamped to other provincesFootnote 15 where they were not registered or where they would not be liable to mita service. The result of all these changes explains why the number of mitayo workers declined from the 14,000 established by Toledo in 1573–1575 to no more than 4,000 by the end of the seventeenth century. That was a fall in excess of seventy per cent, and in the eighteenth century the number declined even further to approximately 3,000.Footnote 16

In the fourth period, from about 1730, an upturn in mining activity meant cash payments from workers became less important. Now, the most important feature was the emergence of kajchas, who, as far as mine owners were concerned, were simply thieves who stole ore during the weekends. The self-employed kajchas undoubtedly challenged and questioned the ownership and the exploitation of the ores, as the kajchas exploited them by processing them in their own rudimentary mills or trapiches (Figure 4). The combination of mitayo and minga workers, as well as that of kajchas and trapiches, was characteristic of the eighteenth century.

In 1812, the first national legislative assembly took place in Cadiz, which, as a result of the French occupation of Spain by Napoleon, claimed to represent the whole of the peninsula and Spanish territory in America. Cadiz therefore represents a climactic point in the political crisis that began in 1808, and scholars have highlighted the political revolution that put an end to the ancien régime. The Assembly of the Cortes de Cádiz formally ended the mita system.

This overview shows that among the most important changes was the switch from corvée labour to payment in cash and a constant reduction of the number of workers going to Potosí, which led to endless complaints and requests by the mine and mill owners. There was also significant discussion of the situation among the authorities.

THE DEBATES ON WHETHER TO EXTEND OR ABOLISH THE MITA (1680–1735): BETWEEN POTOSÍ, LIMA, SEVILLE, AND MADRID

The continuous drop in the number of workers going to Potosí and the changes introduced led to intense debates about reforming Potosí’s mining industry. The owners pushed for a new allocation of labour for the mita, while various members of the bureaucracy opposed their request, considering them a group operating in a region privileged by state policies. I propose to distinguish two phases in the struggle, the first occurring between 1689 and 1700 and the second between 1710 and 1735. In both of them it is fascinating to analyse the requests of Potosí’s guild of mine and mill owners (azogueros).Footnote 17

A first request was made in the form of a petition submitted by representatives of Potosí’s mine and mill owners to the Consejo de Indias, Madrid, 1633.Footnote 18 It is important to note that the mine and mill owners claim to be speaking on behalf of the whole city (Villa Imperial de Potosí). The first paragraph of the petition recalls the importance of the discovery of Peru for the monarchy, for the Empire, and for Spain, and refers to the imperial city of Potosí. The three main measures were for taxes to be reduced (from twenty per cent to ten per cent); a new census to be held, and labour reallocated; and a better distribution of mercury or azogue.

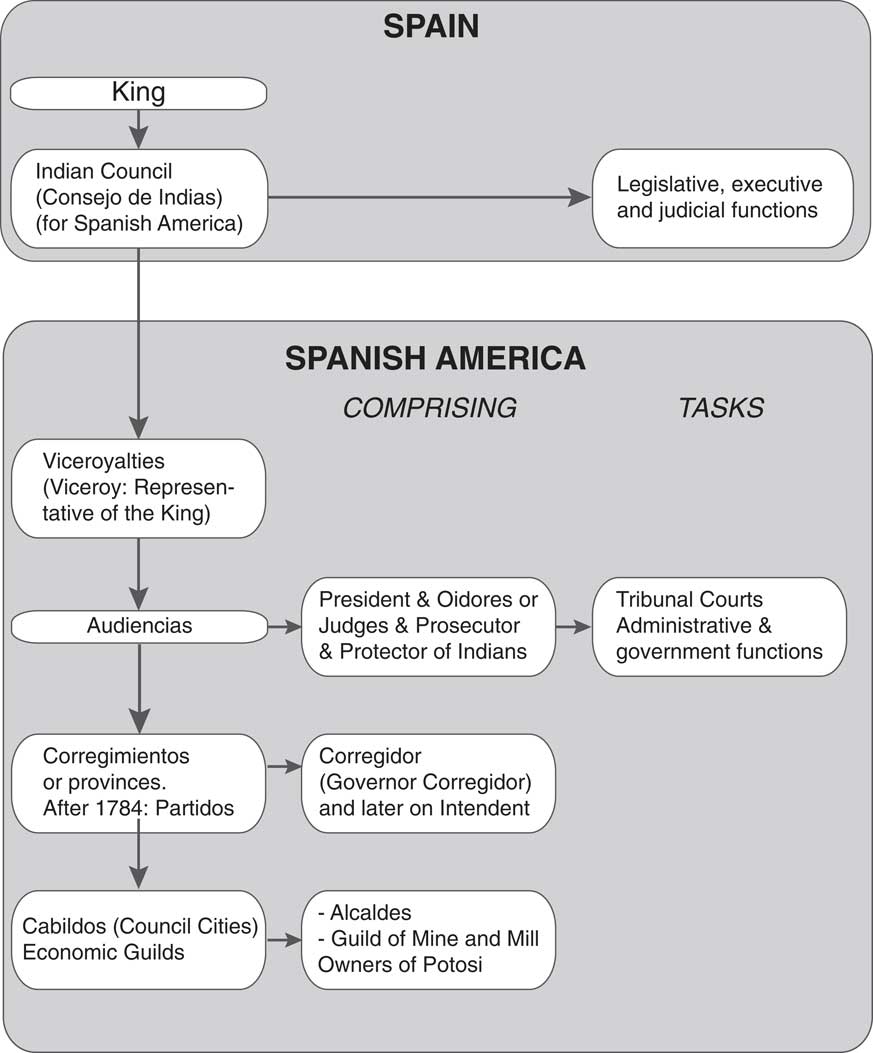

Most interesting is the interaction between the different levels of the public administration: the intervention by members of the audiencias of Lima and Charcas, by the Viceroy of Peru,Footnote 19 and by the Consejo de Indias in Spain (Figures 2 and 3). It is clear that opinions on the matter were expressed at all levels, and the abolition of the mita system was one option discussed. The highest Spanish authorities tried to sustain a policy of equilibrium, which explains the continuation of the mita, for though they did not permit its expansion, they did not support its abolition either.

Figure 2 The Viceroyalty of Peru showing the Audiencia de Lima and the Audiencia Cancillería Real de La Plata de los Charcas, c.1650. Source: http://homepages.udayton.edu/~santamjc/Caribbean1.html.

Figure 3 The political levels of authority in Colonial Spanish America Source: Diagram prepared by the author.

Scrutinizing the procedures and decisions in both phases allows some conclusions. First, it is evident that consecutive viceroys from Peru (Melchor de Navarra, Duke of Palata, 1681–1689; and Melchor Portocarrero, Count of Monclova, 1689–1705) sometimes had different or even opposing labour policies in relation to Potosí. This is not to say that the authorities in Spain did not take a consistent position regarding support for or the abolition of the mita. The reality “on the ground”, though, was that the implementation of state policy was mediated through conflicts and struggles of different groups and sectors, leading to unpredictable consequences. Second, the debates were referred to Spain, where members of the Consejo de Indias intervened to take a decision. Third, Potosí’s mine and mill owners’ guild sent its own representatives to Spain, and their arguments, too, were crucial. Fourth, it is true that, at first glance, the decisions taken do not seem to have changed the labour system radically, although they were the result of negotiations between antagonistic points of view. None of the positions stated predominated, although, while unable to impose its own preference, the mining industry led by the mine and mill owners’ guild did succeed in blocking proposals to abolish the mita, which continued albeit on a smaller scale and with some changes.

The first phase in the debate developed after failure of the great reforms that the Viceroy the Duke of Palata had tried to implement in 1689. He organized a new census to cover a vast region in order to revise the number of mitayos that every village and province was obliged to provide to Potosí. The census was to include the migrant population (forasteros), who had appeared after the previous census of 1575. The idea was to reinvigorate the mita by raising its number from 3,000–4,000 workers to the 12,000–14,000 workers of 1575. The reform also sought to impose tighter fiscal control.

His successor as viceroy, Monclova, adopted a completely different policy. He organized a council in 1691, attended by various authorities of the Viceroyalty of Peru, for the purpose of analysing the situation. This they did for almost fifteenth months, until finally two positions emerged. There were those who pleaded for the mita system to be abolished and those who wished it to be continued.

Initially, the first group, in favour of abolishing the mita, predominated. The mita was considered a form of extortion because it had changed from corvée labour to payment in cash – which favoured owners – with the complicity of a number of authorities. This position explained the reduction in tax revenues from silver going to the Royal Treasury (Real Hacienda) as systematic fiscal fraud, a result not only of the weakening of the monarchy’s economic and political control, but also of the over-exploitation of indigenous labour.Footnote 20 It was at that time that Matías Lagunez, the Prosecutor, or Fiscal, of the Audiencia de Lima, wrote his Discurso sobre la mita. For him, there were two mitas, the one that had been legally sanctioned and the other that was actually practised.Footnote 21 Constant violation of the existing law made the operative mita illegal, and Lagunez also held that there was a network of actors, including indigenous authorities, who were involved in the abuse of indigenous labour for their own purposes. It was Lagunez, too, who developed the important idea that the mining industry was being subsidizedFootnote 22 by the low salaries of the mitayos Footnote 23 and that the Potosí mining centre would be unable to survive if it were forced to pay everyone wages as high as those of the free workers or mingas. There was, then, a conviction that the era of unlimited wealth for Potosí had come to an end, but that it was not true that without the mita (Indians) and Potosí’s wealth Peru itself would not exist.Footnote 24

The competing position took the form of decisive support for mining that basically meant ensuring the best conditions for the sector so that tax revenues would not be endangered. That meant ensuring the flow of and convenient prices for the azogue, or mercury, but also necessitated a sustained supply of mita workers. From that viewpoint, if Potosí failed, everything would be lost: “the Indies would end” and this “would be felt throughout the world”.Footnote 25

The result was a juste milieu (middle way). It was decided not to increase the number of workers for the mita and not to extend it to new regions or to include new peoples (migrants or forasteros) as the Duke of Palata had planned. However, a royal decree issued in Lima in 1692 established a new allocation of workers to just thirty-four mills (leaving twenty-four mills without workers), although their numbers were set at just 4,108 in total or 1,367 per week.Footnote 26 However, the guild of the azogueros was able to reduce workers’ wages.Footnote 27

The documents were duly analysed in Madrid in 1694.Footnote 28 The Consejo de Indias and other administrative bodies decided that the mita should continue but with certain restrictions. A Royal Decree of 1697 (18–II) confirmed the measures introduced in 1692 but ordered the addition of four new points: (i) the wages of unfree workers (mitayos) and free workers (mingas) were to be equalized, (ii) commutation of work for payment in cash was to be forbidden; (iii) the fixed amount in ores required from workers was to be reduced; and (iv) the costs incurred by workers in travelling to Potosí should be paid in advance. Some authorities in the audiencias of Lima and La Plata, along with the Archbishop of La Plata, and the mine and mill owners (azogueros) rejected the measure.Footnote 29 Equalizing wages was one of the more controversial points. Some people believed it was intended to conceal the desired end of the mita.

In the second phase of the debate, the contraction in silver production at Potosí was drastic. It was no accident that four requests (memorials) were presented by the mine and mill owners between 1708 and 1714. In 1719 they opened a debate, once again, about the mita. There were more reports in the 1730s, which culminated in measures taken in 1735–1736 that lasted until the end of the eighteenth century.

Particularly in 1709–1710, the mine and mill owners reiterated old requests, namely that the price of mercury be lowered, that royal taxes be reduced, and that there be a new allocation of workers. The owners demanded more effective intervention by the audiencia to guarantee the number of workers allocated, and complained about the corregidores, the regional authorities of the provinces, whom the owners saw as mainly responsible for the diversion of Indian labour for use in other enterprises and businesses. In 1714, the owners demanded a ban on the conversion of corvée labour into cash payment, a practice that the owners said was against their own interests. They also wished to reduce the two weeks of rest enjoyed by the mitayos to just one week because they could then engage the same mitayos as free labourers for just one week instead of having to do so for two. Footnote 30 Finally, they claimed that a fifty-quintal box of ore cost one hundred pesos, but they obtained just fourteen quintal of silver from it, for which they were paid only ninety-one pesos.Footnote 31

In 1719, the Consejo de Indias in Spain examined a file entitled “Considerations concerning the abolition of the forced labour of the mita”. The arguments in favour of abolition included the deterioration in Potosí’s mines, decreased tax revenues, and the negative consequences of forced labour for the indigenous population. Three main measures were proposed, namely the abolition of the mita, a reduction in the price of mercury (azogue), and tax cuts.Footnote 32 In the event, the region was hit by a major epidemic, which somehow paralysed the decision-making process.

Later, in 1727, the azogueros again requested the abrogation of the 1697 measure, particularly the requirement to equalize wages between unfree and free workers. There followed a lockout in Potosí.Footnote 33 Subsequently, a total of nine reports were written in the 1730s by the magistrates of the Audiencia de Lima and the Audiencia de Charcas. Two ideas coalesced: the “common utility” or the public good for the political body of the kingdom, and the recruitment of free workers during the weeks of rest enjoyed by the unfree mitayos,Footnote 34 the general view being that the allocation of mitayos or unfree labour was inevitable. The main argument of one such report was that such political subordination was not contrary to Christian liberty, that it was one thing to serve, but a completely different thing to be a serf. The Viceroy of Lima sent the votes of the assembly of the magistrates to Spain; most of those magistrates agreed with the mita,Footnote 35 whereupon a new royal decree was issued in Seville in 1732 ordering the continuation of the mita, though calls to equalize the wages for unfree labour and free labour were set aside. The one week of work and two weeks of rest of the mitayos was reconfirmed and Indian migrants (forasteros) were included among the mita workers.Footnote 36

Clearly, the preferred option of the mine and mill owners that their allocation should revert to approximately 14,000 workers instead of 4,000 – a demand they had also submitted to the Viceroy the Duke of Palata – was no longer feasible. However, at least the threat of abolishing the mita never materialized either. The long-awaited demand that taxes be reduced from twenty per cent to ten per cent promulgated by royal decree on 28 January 1735Footnote 37 seems to have been introduced to compensate the persistence of the mine and mill owners, and in response to the reduced purity of the ore in Potosí.

THE WORKERS INITIATIVES: THE SELF-EMPLOYED KAJCHAS AND TRAPICHES

It is certain that one of the most relevant changes in the eighteenth century was the emergence of kajchas, who were associated with the rudimentary ore-grinding mills called trapiches. They were self-employed workers, according to the taxonomy of the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations of the International Institute of Social History (IISH).

The owners of the mines called the kajchas the “weekend thieves”, but the tradition of fairly free access to the ores had existed since the first few decades of Potosí’s mine exploitation. Viceroy Toledo, who established the mita and the amalgamation process, himself stated in the legal regulations he drew up that the owners of the mines were obliged to give the workers a quarter of the mines as “had been done until then”, on condition that they sell the metals they obtained back to the owners of the mines and refineries.Footnote 38 It is possible that such indulgence shown to the indigenous population working on the Cerro de Potosí was considered some sort of compensation and actually originated as the natives began to be denied free access to the ore. What might have looked like a concession had therefore become established as a right, whose origins had been largely lost in the mists of time. The existence of the kajchas meant therefore that neither ownership of the mines, nor the exclusive property rights of the Spanish mine owners were entirely accepted by the workers, who, for their part, insisted on their own rights of access to the silver mines, such as they had had since early times. Similarly, although deprived of actual ownership of the mines, as kajchas the mita and minga workers nevertheless maintained control over a substantial portion of the ore.

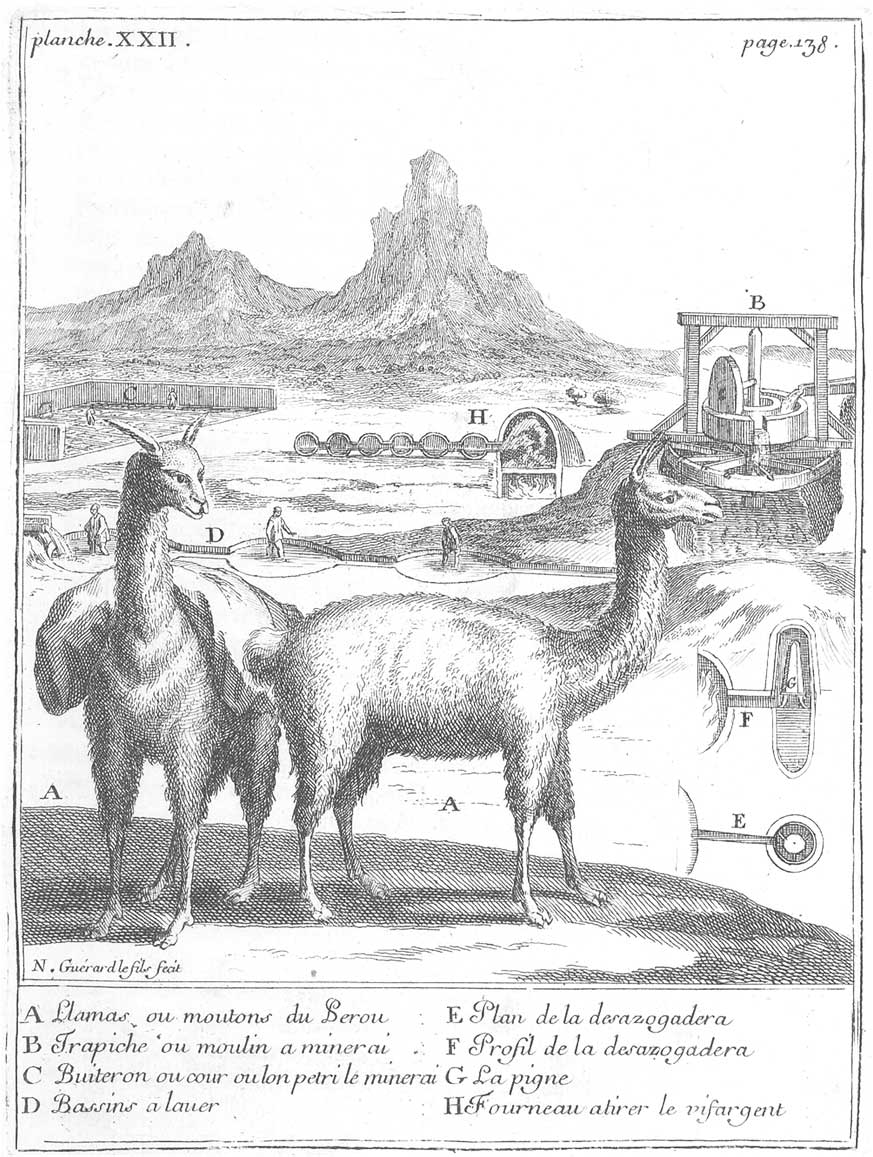

The kajchas exploited the ore, and the role of the trapicheros was to refine it. In 1759, a trapiche (Figure 4) was described as the place where the ore was ground, which was done using large rocksFootnote 39 rather than the sophisticated machinery of a trituration mill or the water mill of the ingenio used for refining. In the trapiches, after ore had been crushed, the powder was mixed with mercury, salt, and sometimes tin. The ore was then washed to create a silver/mercury amalgam, which settled in the water. The amalgam could be sold as it was, directly to the dealers, or it could be “burned” to obtain pure silver that could then be sold to the bank established by the Spanish Crown.Footnote 40

Figure 4 Trapiche according to Frézier, 1732. B=Trapiche mill to crush minerals. D=Ponds to wash the amalgam. H=Furnaces to extract the mercury. Source: Relation du voyage de la mer du Sud aux côtes du Chili, du Perou, et du Bresil, fait pendant les années 1712, 1713 & 1714 par M. Frezier, Paris, 1732, plate XXII, p. 138.

The sources reveal the growing strength of the kajchas and trapiches from 1750 onwards. One of the most interesting aspects of a 1761–1762 report is that more than 200 trapiches were listed. Spaniards owned 58 of them, some were the property of mestizos (those of European and American descent) and mulatos (those of mixed white and black origin), while 160 of the trapiches were in the hands of indigenous people, both men and women.Footnote 41

These self-employed workers and the trapicheros provoked frequent debates about what should be done with them. While the interests of the mine and mill owners were supported by some local authorities who sought to eliminate the kajchas and the trapiches, the higher colonial authorities sometimes opted for a degree of acceptance because of the tax the kajchas paid to the Crown. Official “tolerance” was therefore essentially a tax-driven policy, imposed against the will of the mines’ entrepreneurs, the azogueros.

On the other hand, the detailed daily logbooks of the San Carlos Bank for 1762 recording sales of silver to the bank reveal that the trapicheros numbered almost 500 people and that in relation to 1,500 transactions they accounted for sixteen per cent of total sales (in pesos), while the azogueros accounted for eighty-three per cent. Although the great majority of trapicheros were men, a significant number were women – 39 of more than 200.Footnote 42

It is important to emphasize that some documents noted that the “yndios trapicheros” were also employed not only as kajchas, but also as unfree mitayos and free workers. They included the pick-men in the mines. Such sources might exaggerate the intermingling, but the important thing to note is that the people working in the trapiches were associated with workers in the mines and, certainly in a number of cases, they were the same people.Footnote 43

The independent economy of the kajchas and trapicheros in the eighteenth century is a clear example of a practice that had begun in the sixteenth century and which, by the eighteenth century, had helped improved the situation for mineworkers.

THE MITA AS SLAVERY? FROM DEBATE TO ABOLITION IN 1812

In the final decade of the eighteenth century the mita system had again come close to being abolished. In 1793, Victorián de Villaba,Footnote 44 Attorney General of the Audience de Charcas, wrote his Discurso sobre la mita de Potosí,Footnote 45 using the same title as the abolitionist document written a century earlier by Lagunez. Starting with a religiously inspired motto from St Ambrose (“It is a better thing to save souls for the Lord than to save treasures”), Villaba attacked the mita’s existence, arguing that the mines of Potosí could not be regarded as being controlled by the sovereign, and that even if the work done there was for the public good or for the res publica Footnote 46 (the government and the state) no one had any right to oblige Indians to work there. The response was immediate. Potosí’s highest authority, the Governor Francisco de Paula Sanz and his adviser Pedro Vicente Cañete,Footnote 47 both asserted that, all over the world, since ancient times, mines had been considered to be under the direct dominion of kings, who had duly exploited them;Footnote 48 the Spanish king might therefore exploit the mines directly or indirectly. In the latter case, the king gave his vassals “possession” but not ownership, and for that “concession” received the right of regalia in the form of a proportion of production.

In this great debate between Villaba and Sanz/Cañete, one of the issues discussed was, again, the interpretation of what was public and whether it was rational to continue with a policy that favoured channelling labour to Potosí. Villaba clearly opposed Sanz and Cañete, who, in 1787, wrote a guide to the government of Potosí and a legal code for the mines.Footnote 49 Both men, Sanz and Cañete, thought the mita constituted “the principal centre and support of the welfare of the state” and that without “forced Indians” it would not be possible to make progress.Footnote 50

Villaba asserted instead that mining was not a “public” affair controlled by either the nation, or the sovereign because it benefited private actors, namely the mine and mill owners – the azogueros Footnote 51 – and so effectively represented a policy that today we would call “subvention” for a privileged sector and economic group. As a result of this royal concession, the mine and mill owners benefited from the mita, which was designed to “extract the immense wealth of the ramifications of the earth” for the treasury, for the kingdom, and for the splendour and glory of the monarchy.Footnote 52

Villaba’s point of view contained another crucial idea. The abundance of money was not the “nerve of the state and the blood of the body politic”, because it was a universal commodityFootnote 53 that did not create national happiness. Potosí, said Villaba, remained an example of the fact that “in mining regions, we see only the opulence of the few and the misery of infinite numbers”.

A reply to Villaba was published in 1793Footnote 54 and some years later, in 1796, the different corporations of Potosí (mainly the mine and mill owners, and the civic authorities) drafted an “Apologetic Representation” expressing their unity in opposition to Villaba, who had published a paper openly calling the mita a tyranny. They attacked Villaba for receiving the support of the Church and accused the priests of a “scandalous” use of indigenous labour, which was why the Church opposed the mita. The corporations also accused the audiencia of meddling in the “exclusive dominion” of the government of Potosí by acting as a “theocratic government”. They asserted that Villaba wanted to abolish the mita “to make his name famous in America” and that the real offence was “dismantling the use of the earth’s immense riches and impeding the glory and splendour of the Monarchy”. Finally, they asserted that “those powerful men that the natives hear, listen to, and faithfully obey [Villaba and the Indian authorities] sought to win them at the cost of the ruin of sovereignty and the royal jurisdiction, which constitutes a state offence and a crime of lèse-patria and lèse-majesté.”Footnote 55

What was the outcome of this process? The impossibility, once again, of abolishing the mita, the unfeasibility of broadening it, and the paralysis stemming from the Mining Code. However, above all it was a fierce attack on the institution of the mita. Villaba, in the first paragraph of his Discurso sobre la mita, insisted that it was “temporary slavery”, even if the Indians were not legally slaves.Footnote 56 Nevertheless, Villaba’s was clearly a strategy intended to portray the mine owners as slave owners and to delegitimize the mita, and it seems that his approach did indeed affect the number of mitayo workers going to Potosí.

The mita became an important issue over the following decades. The arguments used against it reappeared for example in 1802 in the writings of Mariano Moreno, later a political leader of the Buenos Aires movement for independence. Other radical writers of the period put forward the same arguments.Footnote 57

In 1810, Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of the Iberian Peninsula prompted a political crisis in Spain, with, as a result, the first sessions of the Cortes de Cádiz – the first Assembly of Spain and the Americas. Representatives repeatedly discussed the situation of the indigenous people.Footnote 58 Those who argued against the mita in Cadiz were well-known individuals who would eventually go on to have long political careers in the independent states of Latin America, men of the same generation as Simón Bolívar, such as José Joaquín de Olmedo, the delegate for Guayaquil, or Florencio del Castillo of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Although Castillo and Olmedo might not have been familiar with Villaba’s writings, they made use of all the arguments generally deployed about the mita, and added some new liberalist-inspired ones of their own. In their view, the mita system was a symbol of the conquest itself and of barbarously feudal legislation.Footnote 59 So abolition of the mita, already a moribund institution in any case, was duly decreed on 21 October 1812.

CONCLUSIONS

We can arrive at a better understanding of the labour system in Potosí, with its continuities as much as its shifts, by closely examining the official policies relating to it, and the discussions concerning those policies. Official policy was, of course, promoted from above, first by the different levels of the Spanish monarchy – whether in Madrid, Seville, Lima, or Potosí – and then modified by the requests at a local level of the mine and mill owners. We can also consider the strategies of workers, who, of course, had to respond to their situation from below.

From the very beginning, in Colonial Spanish America the mita raised the problem of “personal service”; that is to say, the tension between the freedom of the Indians considered as vassals of the Crown and the obligations imposed on them to work in the mines. However, it was equally clear that coercion was based on two commonly articulated reasons for the silver mining industry’s economic importance: first, its role in contributing to the public good, and more specifically its contribution through tax to the financial well-being of the monarchy.

The decrease in production, tax yield, and in the number of workers going to Potosí during the seventeenth century gave rise to competing requests and proposals, particularly from the mine and mill owners who championed a new allocation of labour for their enterprises. Their failure to secure their desired reform prompted decades of reports, proposals, and debates between the authorities at the different political levels of the Spanish monarchy between 1692 and 1732. A hundred years after its implementation, the mita could not be revitalized from its now diminished role, as the mine and mill owners from Potosí had hopefully proposed, although its abolition as advocated by other economic and political groups did not come about either. Potosí’s mining sector had certainly lost ground, but the Spanish Crown dared not put an end to the industry’s privilege because of the resources it still generated. That situation explains why the mita continued despite the changes. For example, in the eighteenth century there were no more than 3,000 workers, compared with 14,000 at the end of the sixteenth century.

The labour system in the Potosí mines in the eighteenth century emerges as much more complex, the result of intertwined factors. State policies did not revitalize it by increasing the number of mita labourers, but they did decrease taxes and facilitated access to mercury to boost production. For the mine and ore-mill owners the mita was important even after the number of mitayos had decreased considerably, because it was the main mechanism for attracting a significant workforce to Potosí from a population that already had its own land and resources. The workers themselves showed their agency and sought additional gains by exploiting the mines during weekends. The mitayos and mingas could simultaneously be kajchas or have agreements with them. The kajchas were also closely associated with the trapiches, and both of them revealed their empowerment in the mid-eighteenth century, when the Potosí mountain would be divided between the owners of the mines and the kajchas.Footnote 60

In the mita debate at the end of the colonial period, Villaba’s discourse in favour of the Indians had much more to do with enlightened concepts of wealth, and humane Christian values. This humanistic perspective was present among the intellectual generation of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, who saw the Indians as victims of oppression. By about 1809, the mita became the symbol of the conquest, with its brutal and feudal legislation, and the obligations of the system represented the absence of freedom for the Indians. The mita became a powerful symbol of America itself in the minds of some, including a number of American assembly members of the Cortes de Cádiz in 1812. However, the paradox is that the vision of Villaba, who was the most vigorous to defend the Indians, also did most to paint a pitiful picture of their agency, which historians are now trying to overcome.