Father Augustine Baker, spiritual advisor at the English Benedictine convent at Cambrai shortly after its foundation in 1623 wrote to his Protestant book-collector friend, Robert Cotton, requesting books for the nuns because; ‘Thair lives being contemplative the common books of the worlde are not for their purpose, and little or nothing is in thes daies printed in English that is proper for them.’Footnote 1

This short quotation provides a raft of insights into the formation of book collections in the recently founded English convents in exile. We see the influence that male confessors, spiritual advisors and directors exercised over the selection of texts they considered appropriate for the nuns in their communities. Father Baker here consciously sets his spiritual disciples apart from lay women, their vows differentiating and separating them, as did the enclosure. The nuns needed specialist texts to support their religious life but these were difficult to obtain from booksellers. Baker was drawing on his personal contacts, in this case a Protestant, to find suitable reading material. In particular Baker was looking for books in English on the spirituality of the mystics for private reading. These were intended to support the personal spiritual development of the choir nuns at the Benedictine convent at Cambrai who were following his methods. He knew his friend collected medieval religious and literary manuscripts including works on the mystics he sought.Footnote 2 His wish to restrict the selection of texts available to nuns was reinforced by the constitutions which he drew up for Cambrai. Through them he legislated for the external Visitor to keep a close watch on the contents of the library.

Let the Vicarius have a special care that no books written or printed (even papers of instruction or devotion) that savour not of a religious Monasticall spirit, or that tend not unto it, be kept in the Monasterie: and therefore let the catalogue be examined at everie Visit, and at such time as the Ordinarie shall judge fit.Footnote 3

How far was this situation replicated across the English convents? How much do we know about books and about how collections were formed in the foundation period of the English convents in exile? This paper will examine evidence from the foundation period of the English convents in exile relating to the process of creating the book collections considered crucial to the religious life. It will focus on the first hundred years of the new foundations and explore the influences on the selection and acquisition of books which resulted in the creation of impressive libraries which remain little known to outsiders.Footnote 4

Research on writing in the convents throws light on what the English nuns were reading; however to date, little research has been carried out on the book collections at the convents.Footnote 5 There are a number of questions regarding conventual libraries, worth considering in order to understand better the religious life and intellectual culture of the English convents in exile. For instance; what influenced the selection of titles and the languages chosen? How did suitable books reach the convents? How far were the kinds of books needed by the convents really distinct from those read by lay women? This paper will consider a wide range of surviving evidence to seek answers to these questions. Recent publication of catalogues on the web and in print provide much needed data, although much remains to be done and any conclusions in this paper should be read as suggestive rather than definitive.

Sources

Evidence of book collections from the English convents in exile survives either as books, both printed and manuscript, or as lists and it suggests the nuns owned considerable libraries by the end of the seventeenth century. As is inevitable for convents so deeply affected by the impact of a number of traumatic external events including war, fire and earthquake, evidence, although substantial, is incomplete. Only one convent closed before the French Revolution, but subsequent closures and amalgamations make it difficult to trace some libraries, and the survival rates for books vary considerably. Ironically, we have the most complete listing of the library at Cambrai where virtually no books have survived.Footnote 6 However, in spite of these events much remains from the book collections to provide core data on which to build discussion.Footnote 7 Two scholarly online catalogues of convent collections have made publicly available data relating to the printed books from the Bridgettine library at Lisbon and the amalgamated libraries from the four Poor Clare convents.Footnote 8 The Bridgettines returned to England from Lisbon bringing with them 250 books published between 1540 and 1700. These were kept in their library until the recent closure of their convent at South Brent in Devon led them to hand over the books to the University of Exeter for safe-keeping. The orderly removal of the Poor Clare convent from Aire-sur-la-Lys in 1799, when they were able to bring 79 crates including part of the library with them, means that we have more from Aire than the others.Footnote 9 Some 105 printed volumes and three devotional manuscripts in the catalogue at Durham date from before 1700, other seventeenth century material remains with the community. Some books originating from the Franciscan convent in Bruges, after a tortuous journey since the French Revolution, have recently been sent to Durham and have been catalogued with those of the Poor Clares under the heading ‘Woodchester’.

The Sepulchrine canonesses were a community who carefully planned their removal from Liège. They brought with them 800 boxes of possessions, losing only one box on the way. Included in these were many books from their library that are still with the community: a modern catalogue created by their archivist lists 263 works published before 1699.Footnote 10 The ‘Old Library’ at the Bar Convent, York where the Mary Ward Sisters have lived since 1686 has more than 400 books printed before 1700. Over 1000 Carmelite books from the exile period are carefully looked after by Sisters Constance Fitzgerald and Colette Ackerman in Baltimore Carmel in the United States, the monastery where the successors to the daughter house founded at Port Tobacco from Hoogstraten and Antwerp still live.Footnote 11

Figure 1 Part of the collection of early books from the Benedictine convent, Ghent: now at Douai Archives and Library. Reproduced with permission of Abbot Geoffrey Scott, Douai Abbey.

The new (2010) library and archive centre created at Douai Abbey near Reading under the leadership of Abbot Geoffrey Scott OSB is gathering books and archives from enclosed convents which no longer have storage or have closed. Cataloguing here is taking place as funding becomes available. Many of the books from the Brussels Benedictines are at Douai and among recent arrivals in the library are a substantial recusant collection from the Benedictine convent at Ghent, another from the Dominicans who had a convent in Brussels and part of the Carmelite collections from Antwerp and Lierre. Surviving convents still hold substantial numbers of books from the exile period; for instance the Augustinian Canonesses at the English Convent in Bruges have a significant library of their own, as well as acting as a repository for books from other orders who were displaced at the time of the Revolution.Footnote 12

The collections from Cambrai and its daughter house in Paris need to be considered together. The impact of the French Revolution on the Benedictine convent at Cambrai was devastating. Few of the books from Cambrai survived, since the nuns were forbidden to carry out anything. More has survived from Paris, where, according to Julia Bolton Holloway, 2,245 books and manuscripts were brought to England.Footnote 13 An important source for the libraries of the two convents is the recent work of the late Dr Jan Rhodes who edited the revolutionary listing of some 3953, mainly printed, items in the possession of the nuns at Cambrai when they were seized in October 1793. The revolutionary government intended to draw up inventories of the cultural heritage of France.Footnote 14 Dr Rhodes has also edited ‘Mazarine 4058’, a catalogue of the manuscript books belonging to the daughter house in Paris.Footnote 15 Other convents provide glimpses into their collections through short lists and individual references which can gradually be pieced together. For instance, some information about the early books at St Monica’s, Louvain, the home of the Augustinian Canonesses, can be seen in a list contained in a MS Miscellany. This also gives the appropriate days when they should be read.Footnote 16 We have some knowledge of the books of the Benedictine convent at Pontoise from the auction records of the convent in 1786: the library was appraised by the auctioneers as comprising more than 250 books and 100 incomplete volumes in French, Latin and English, on different subjects, badly bound and not worth a more detailed description.Footnote 17

The complex post-revolutionary history of the English convents has further compromised the survival of their books. Multiple removals during the search for permanent homes once in England, and amalgamations within orders in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries led to some book sales. Closures and dispersals have further spread the collections across academic libraries on both sides of the Atlantic, often identifiable through name inscriptions. A number of monastic books have been digitised and form part of the EEBO collections. The particular case of the extensive depletion of the libraries of two Benedictine convents, at Brussels and Ypres as well as some of the male institutions, was discussed in a paper given by Nicolas Kiessling of the University of Texas at Austin at the English Benedictine History Commission Symposium held at Colwich Abbey in April 2012.Footnote 18 However, in spite of all these difficulties, thousands of books have survived and thousands more are listed and form the basis of this survey.

Distribution of time: reading in the conventsFootnote 19

The pattern of the monastic day varied across the convents and according to special events such as feasts, retreats or the liturgical seasons: the time spent reading varied accordingly. The diagram below, based on a Sepulchrine document of the mid-seventeenth century, allows us to see how often reading and books were part of a normal day at Liège.Footnote 20 Other convents followed a similar pattern with their own variations built in. For instance, at the Blue Nuns in Paris significantly less time was allocated for reading: about half an hour after None (9th hour) and later, between 2.30 and 5.30, nuns could choose between retiring to their cells to work, to pray, or to read; or to walk silently in the garden.Footnote 21 After supper they could continue the same. Reading was permissible as an alternative to meditation.

A day in the life of the Sepulchrines at Liège

Books were essential for all aspects of the religious life: at the daily office in Church, in private prayer and meditation in cells, for the formation of novices and the spiritual development of nuns and for communal reading at meal times. In addition, the printed texts of the appropriate monastic rule and individual constitutions provided for every member were essential to support the regulation of daily life and spirituality of a particular convent.

The English convents in exile can be described as transnational textual communities; they were self-consciously English, yet they operated within a European Tridentine culture. Liturgical books for the performance of daily office were in Latin for the choir nuns while lay sisters followed the Little Office in English.Footnote 22 These books were not difficult to obtain because most were used by local communities too, but there was a particular challenge for the new foundations: the sourcing of appropriate texts in English for spiritual reading. A high proportion of such books in French appear in most collections: fortunately in many convents there were nuns who, fluent in the local languages, were able to make translations for those who were not.Footnote 23

Convent Libraries

Given the ultimate size of the collections, it is perhaps surprising that there is no evidence in surviving drawings from the seventeenth century of the creation of a separate designated room for books, although there are manuscript references to ‘libraries’ and occasionally to ‘librarians’. The constitutions for Cambrai required that ‘All the books must belong to the common librarie, & be keept under lock, & have written on them the name of the monasterie, & be common to all indifferentlie.’Footnote 24 At Lisbon it was specified;

… wee doe ordeine that there bee made a Register of all the bookes belonging to the common Librarie: of which bookes, one Sister whome the Abbis shall appointe shall have a care: neither shall it bee lawe full for anie one to carrie anie booke oute of the saied Librarie; or to keepe it with him selfe; withoute leave of the Abbis.Footnote 25

Clare Newport at the Benedictines Paris was described in her obituary as the librarian for twenty years who ‘took great care and paines to preserve all the Bookes but perticulerly those presious treasurs of our house, venerable Father Baker’s manuscrips’. Her sister left a bequest which was used to purchase the house at Champ d’Alouette and to make a new library; ‘for the better conserving the afore sayd Treasurs’.Footnote 26 Her obituary records that it was reading the works of Father Baker that drew her to the religious life in the first place.

The explanation for the lack of a room designated as ‘library’ lies primarily in the division of the book collection according to places where titles were most likely to be used and the size of the books themselves. Since many books (apart from those for communal use in the church or refectory) were in small format it would be a long time before they required more shelf space than a locked cupboard. As a point of comparison we might set convent book collections against the Countess of Bridgewater’s 1633 library reconstructed visually by Heidi Brayman Hackel. She found that 241 volumes occupied nearly 30 feet of shelf space.Footnote 27 The Abbess had her own books to assist her in writing homilies she presented in Chapter and to allow her to provide texts for nuns when she was counselling them. One copy of Augustine Baker’s Holy Practises of a Devine Lover (1657), at the Benedictine convent in Brussels, is marked ‘Lady Abbess’ Library’, and a French Office for Holy Week is inscribed ‘This book belongs to our R Mother Abbess’. The Abbess played a significant role in the selection of texts directly and indirectly. For instance the rule at the Blue Nuns in Paris stated that the Abbess ‘shall take care that no Manuscript or Book be brought or receiv’d into the Monastery, which may be any way suspected as unfit for Religious persons’.Footnote 28 At the Benedictines in Paris, Reverend Mother was placed in charge of the ‘secret books’: these included the lives of Father Baker and Dame Gertrude More, works by Harphius and the Ladder of perfection.Footnote 29 Indirectly, the Abbess expected to play a key role in the choice of Confessor who, as we shall see below, in turn influenced the choice of books in the library.

The Infirmary had its own book collection because some Sisters might be confined to bed long term and unable to attend chapel. A special dispensation was given to those unable to read: they were allowed to listen to a Sister reading to them in a quiet voice. Books were specifically marked for keeping in the Infirmary: at the Poor Clares, a copy of Eugene Roger, 1664, La Terre Sainte, a topographical description of the holy land is inscribed ‘This booke belongs to the infirmary. Not to be taken from thence without leave’. A copy of The ways of the Cross (1676) is marked for the infirmary at the Benedictines, Dunkirk.

Other books are inscribed for the Novice house where many books were needed for teaching and formation. On first joining the convent, novices were provided with a copy of the rule and constitutions in order to become familiar with the contents. Novice mistresses also taught choir novices how to read, meditate and make notes of their reading. They were also made familiar with the Latin of the liturgy. Books for the novitiate might be labeled ‘Belonging to the Convict’.Footnote 30 A copy of the 1700 edition of the psalms at Bruges is inscribed ‘Noviceship’ together with the name Mary Clementina Howell who died in 1832, an example of a book being used over a long period of time.Footnote 31 A Douay Old Testament (1610) from the Poor Clares at Rouen is inscribed ‘Lent to the Novishous of Jesus Maria Joseph’ with an additional note in volume 2; ‘Dear Mother Abbis has given me leave to have these books for my use but they are not to be given out from the house’.

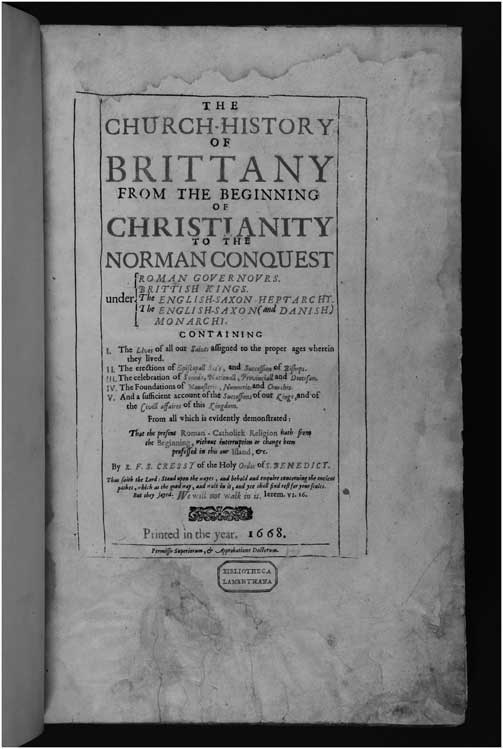

Figure 2 Title page, Serenus Cressy, OSB, Church-history of Brittany, 1668, one of the works for reading in the refectory. Copy from Lambeth Palace Library: reproduced with permission of Lambeth Palace Library.

The chantress was responsible for books relating to the liturgy with all its variations, for choosing readers and singers and providing training to see that all was performed properly. She kept the books near the Chapel. At the English convent in Bruges the chantress’s office containing her books is just outside the choir nuns’ entrance to the church. A copy of a litany from the Brussels Benedictines is marked very precisely; ‘This belongs to the Chantress on the Abbess’s side’.Footnote 32 It is helpfully printed in a large type face, eleven lines to a page showing verses and responses.

Some books are marked specifically for community reading: for instance Nicolas Caussin’s, Holy Court, fourth tome (1638) is inscribed ‘Str Mary Smith Book given for the reading stand in the refectory Sion’.Footnote 33 Texts marked in this way were often kept in a nearby cupboard ready for use. At Liège, as in other convents, refectory readings were taken from books such as, The Flowers of the Lives of the most renowned Saincts of the Three kingdoms (1632) by Jerome Porter, a book that was helpfully structured for reading on anniversaries and linked the convents to their English Catholic past.

The term ‘ownership’ was variously understood in the convents. It was generally accepted that books were, as stated in the constitutions, the common property of the convent, although individuals were given permission to keep a few in their cells. A book such as the Rule or a psalter might remain with a nun for many years. Anne Meynell inscribed the title page of her copy of the rules of her convent in Paris and dated it.Footnote 34 Others were kept for a rather shorter time; perhaps taken into a cell as a spiritual text suitable for providing material for personal devotions where a sister would extract sentences to make her own compilations.Footnote 35 ‘Ownership’ by an individual appears to have been temporary and qualified by additional text. For instance permission from the Mother superior can be seen in a few volumes: ‘with permission’; ‘with licence of superiors’; ‘lent by holy obedience’; and ‘with leave’.Footnote 36 Lorenzo Scupoli’s Christian Pilgrim in his conflict and conquest (1652) from Dunkirk was inscribed ‘for the use of Sister Mary Barbara Bede’.

Some texts became personal (although often anonymously) with the additions of prayers or meditations on blank pages within the bindings. In such cases books appear to have been treated as practical working texts to serve the religious life of the sisters rather than as objects of reverence.

There is only fragmentary evidence about the acquisition process in manuscript sources. Accounts show that the community might purchase essential liturgical works, although expense led them to make as many scribal copies as they could.Footnote 37 Dame Dorothy Cary’s obituary explained; ‘She had made herself particularly useful with her pen, being so expert and industrious in copying which in those days when books and printing were so expensive was very serviceable. She copied many retreats, meditations etc for common use.’Footnote 38 The convents were frugal with their resources, making do and mending as often as they could. Some of their books contain multiple repairs, replacements of sections and corrections using whatever came to hand. Skills in rebinding and stitching allowed the repurposing of service books over many centuries.

Figure 3 Copy of An Instruction to performe with fruit the Devotion of Ten Fridays in Honour of St Francis Xaverius, St Omer, 1690? from Benedictines, Dunkirk with missing title page. Reproduced with permission of Abbot Geoffrey Scott, Douai Abbey.

Without formal contemporary library catalogues it impossible to know when a book entered a collection, but the presence of a name of an identifiable donor or a borrower provides a date by which we know it to have been added. A rare surviving book from Cambrai, Cuthbert Fursden’s translation of Gregory’s Dialogues Book II & Rule of St Benedict is inscribed ‘with Superiours permition for the use of Sister Margaret Swinburne. This was given me by my Br. Henery who Departed this Life on trinity Sunday the 15 of June Requiescat in Pace 1690’.Footnote 39 Such evidence although fragmentary, indicates that some candidates, when they entered, brought with them books from their family. Jenna Lay has located a copy of Southwell’s Mary Magdalens Funerall Teares from the Dominican library in Brussels. The inscription records ‘the poor sinner Sister Magdalen Sheldon’ having been given the copy by ‘her Deare Aunt Mrs Jane Wake of whome let the Charitable reader be mindfull of in yr prayers’.Footnote 40 The contemporary binding of dark green velvet is unlike the usual run of convent bindings and supports its origin as a lay donation. Another example from the British Library, The Flaming Hart (1642) a life of St Teresa is inscribed ‘given to sister Frances Xaveria by her Dear Mother’.Footnote 41 One copy of Caussin’s Holy Court (1663) at Lisbon was marked ‘Ex dono Dna Ursula Fermor 1664’.Footnote 42 Name inscriptions show that some books remained in use in convent communities for long periods of time: up to two hundred years in some cases.Footnote 43 Occasionally changes to the liturgy were incorporated into the books using marginal notes and additions in the endpapers, even, in a few extreme cases, by changes to the structure of the binding in order to add new sections.Footnote 44 The first five names in a Latin psalter from the Benedictines at Brussels shows the psalter in use from its arrival in the monastery to the beginning of the nineteenth century. The first name is Margaret Curson, who was professed in 1612, the fifth is Mary Ann Rayment professed in 1774: later names show that it continued to be used until well into the nineteenth century.Footnote 45

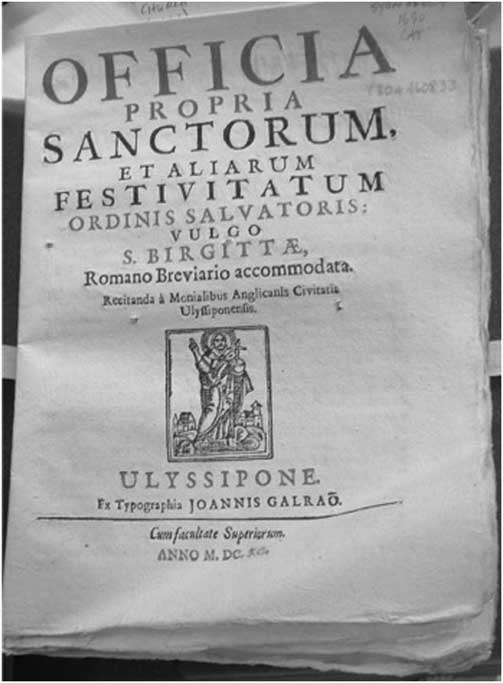

Figure 4 Used copy of Officia Propria Sanctorum from the Bridgettine convent in Lisbon altered to accommodate changing liturgical practice in the twentieth century. Reproduced courtesy of Special Collections, University of Exeter.

Figure 5 An unbound, unused copy of the same text. Reproduced courtesy of Special Collections, University of Exeter.

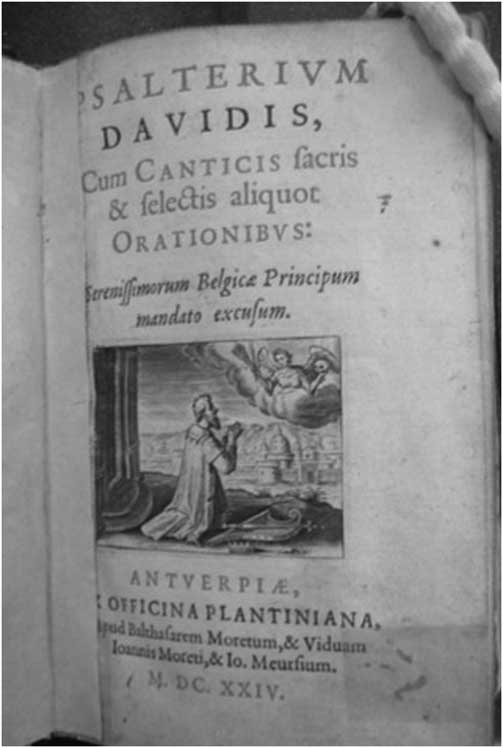

Figure 6 Psalterium Davidis, Antwerp, 1610 from Benedictine convent, Brussels, with later inscriptions. Reproduced with permission of Abbot Geoffrey Scott, Douai Abbey.

Figure 7 Another edition of the Plantin Psalter from the Bridgettines, Lisbon showing signs of wear and mending but with no inscriptions. Reproduced courtesy of Special Collections, University of Exeter.

Convent book collections: Lay women’s books of piety

In order to understand the formation of the collections, it is important to look at the prevailing influences on the reading habits of girls and women prior to their entry into religious life. Even before they left their families some candidates had encountered texts which they would describe subsequently as ‘life-changing’.Footnote 46 Many postulants were mature women in their twenties and thirties who had made the decision to enter the convent without any direct experience or sight of the religious life, other than that which they had found in books.Footnote 47 Mary Birkbeck who professed as a Carmelite aged 29 recorded that reading Francis de Sales’s Introduction to a Devout Life led her to become a nun. Her Vita also relates how when invited to choose a single volume from a priest’s library, she picked randomly the life of St Teresa… which drew her to the Carmelites.Footnote 48 As a child, Margaret Mostyn led a life carefully regulated by her grandmother ending each day with ‘an hour of prayer, afterwards catechism, supper, reading of spiritual books & so to bed’.Footnote 49

Research on the family backgrounds of members of the convents for the ‘Who Were the Nuns?’ project has shown that many came from gentry and landed families: households where books would have been readily available and the education of girls generally encouraged.Footnote 50 Among the sizeable book collections discussed by J.T. Cliffe are those owned by two Warwickshire families, the Sheldons of Weston and Beoley and the Lucys of Charlecote. Several of their daughters became nuns in the English convents in the seventeenth century.Footnote 51 William Blundell of Little Crosby in Lancashire with his seven daughters—five of whom became Poor Clares—and three sons, had a large library. He taught all his children to read and write in English and Latin and later sent four of his daughters to convent schools. Other men in the Blundell family showed a similar interest in the education of girls.Footnote 52

All candidates wishing to become choir nuns had to be competent in reading and writing, and they had to demonstrate the ability to learn enough Latin to participate in Divine Office before they were accepted by the communities. A lack of formal schooling for girls in the seventeenth century places the education of girls mainly within the household. Here they were educated alongside their brothers or taught by their mothers, who were themselves educated.Footnote 53 Taking just one example from convent sources, evidence of parental interest in the education of daughters can be seen the lives of nine nuns connected with the family of Sir Thomas More. Margaret Clement, for instance, was taught Greek and Latin by her parents before joining the school of the Flemish convent of St Ursula’s in 1551 aged 12.Footnote 54 Such examples can be replicated elsewhere—although the degree of proficiency in Latin in the extended More family was unusual. Among candidates for religious profession it is more usual to find an interest in books, the ability to read in the vernacular in English and, in some, fluency in French.Footnote 55 Lack of space precludes further discussion on the education of Catholic girls here; it is enough to note that restricted linguistic abilities particularly in Latin made the availability of translations especially important to the convents in exile. Some convents encouraged young candidates to learn French before profession with the result that the proportion of books in French in convent libraries varies.

How did Catholic readers in England at the end of the sixteenth century manage to locate and acquire texts? Legal restrictions on Catholic publishing and distribution continued well into the seventeenth century limiting the supply of pious books in English. Thomas Clancy’s research estimated that Catholic books in English constituted only 2% of the total published output for the seventeenth century, with most of them concentrated at the end of the period during the reign of James II. Nevertheless the picture regarding access to Catholic reading matter was less bleak than that statistic suggests.Footnote 56 Research by scholars such as John Roberts, Alexandra Walsham and Alison Shell reveals just how many pious books both printed and in manuscript were available to English Catholics. These were being read by Catholic lay men and women and by others from diverse religious persuasions, on both sides of the channel, from the latter part of the sixteenth century onwards.Footnote 57 Walsham even refers to a ‘vibrant book culture’ among Catholics.Footnote 58 New translations from Spanish of spiritual guidance became popular in the sixteenth century. Among them were Richard Hopkins’ (d. 1590) translation of Luis de Granada Of prayer and meditation (Paris, 1582, and Rouen 1584), Gaspar Loarte, Instructions and advertisements how to meditate the misteries of the rosarie… [London, c. 1579], translated by John Fen (d. 1614) who later became confessor to the nuns at Louvain; and Robert Southwell’s Mary Magdalens Funeral teares (London 1592).Footnote 59 Southwell and Granada were popular with lay Catholic and Protestant readers alike and both titles also appear in many convent collections in the seventeenth century.Footnote 60

As well as owning and reading books, women were involved in Catholic literary culture in other ways. For instance, the widespread circulation of texts in manuscript by women, discussed by scholars such as Helen Hackett, is also important in a study of women’s piety and reading.Footnote 61 Their participation in the creation and distribution of new compilations and miscellanies show women as active readers and editors. In her study of Constance Fowler’s ‘Miscellany’, Hackett shows that Constance included religious poems written by women from a Catholic tradition, as well as four poems by Robert Southwell himself. These were all texts that were considered particularly suitable for women.Footnote 62 Several women from this extended network became members of the English convents and provide evidence of continuing interest in books after they joined. For instance, we can precisely date the appearance in the library at Liège of a volume, The Life of the Blessed Virgin, Saint Catharine of Siena (1609) inscribed ‘Gertrude Aston my booke 1658’; the date she arrived as a candidate for admission aged 21.Footnote 63 However she had problems learning Latin and felt unable to continue in the convent, she returned to England in the following October. According to her ‘Life’ she met a Carmelite Father who taught her the practice of mental prayer and advised her to read good books, in particular the works of St Teresa. As a result she finally professed as a Carmelite at Lierre in 1672.Footnote 64 Another Catholic woman involved in print culture became a significant patron of Catholic writing. Anne Howard, countess of Arundel (1557–1630) grew up as a Protestant, but later took the religion of her mother and grandmother. Anne Howard supported the Jesuit priest and poet Robert Southwell whose books feature in a number of places in this paper.Footnote 65

We know that pious lay women both Catholic and Protestant spent a considerable amount of time in prayer and meditation at home. Divisions between Protestant and Catholic devotional practices were not always clear cut and there are some titles which are shared across domestic libraries. There is space here to give only a few examples.Footnote 66 The library catalogue of the educated, pious Protestant, Frances Egerton, Countess of Bridgewater (1585–1636) contained large number of religious works, identified by Heidi Brayman Hackel as making up half the total.Footnote 67 The surviving record of her collection consists of a catalogue listing 241 books in three dated lists. The countess’s Catholic books include a Jesus Psalter, three different works by Southwell including Mary Magdalens Funeral teares, and Prayers and Meditacions, by Granada.Footnote 68 At the same time her Protestant allegiance can be seen in the ownership of works of Protestant polemic including two virulently anti-Catholic tracts; John Rawlinson’s The Romish Judas, and Thomas Morton’s The Grand Imposture of the (now) Church of Rome.Footnote 69 Among the books provided by Lady Sharington (d. 1607) for her daughter, the Protestant Grace Mildmay (c. 1152–1620) to read while she was growing up were Thomas à Kempis Imitatio Christi and Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Grace was encouraged to meditate on a daily basis and she later composed a work of 912 folios of spiritual meditations.Footnote 70 The Protestant Lady Anne Clifford’s reading included several Catholic texts, among them were St. Augustine’s, City of God, Eusebius’s, History of the Church, and Robert Persons’s First booke of the Christian Exercise. The majority of her reading material, however, was clearly Protestant.Footnote 71

It is essential to distinguish between Protestant and Catholic versions of the same popular titles. For instance, Lady Anne wrote that her cousin was reading to her both the Jesuit Robert Persons’s First Booke of the Christian Exercise Appertayning to Resolution, (1582) and Edmund Bunny’s 1584 edition of this. The latter is a Protestant version of Persons’s text.Footnote 72 The case of Thomas à Kempis’s, most popular work The Imitation of Christ is a particularly interesting one. Protestant versions of the text in English were published as early as 1567 with the best known translation by Thomas Rogers in 1580, a version which went to fourteen editions before 1609.Footnote 73 These versions omit problematic Catholic sections including Book 4 on the Blessed Sacrament and, as Walsham describes it, ‘bowdlerize’ the text to make it acceptable to Protestant readers.Footnote 74 Rogers’ 1580 edition was owned by the Countess of Bridgewater; a Latin Protestant version was owned by the scholarly, protestant Lady Mildred Cecil.Footnote 75 Fewer printed copies of The Imitation of Christ in English were available for Catholics in the period. After the translation by the Bridgettine, Richard Whitford in 1530, no new Catholic versions in English were made until the translation by the Jesuit, Anthony Hoskins in 1615.Footnote 76 A second translation into English by Miles Carre, confessor to the English Augustinian Canonesses in Paris was published in 1636 and is found in most convent libraries, and, in several places, in multiple copies.Footnote 77

Although clearly there were a number of books that appeared in the collections of both pious lay women and the convents, it is important to distinguish between their respective reading practices. The spiritual development of the choir nuns was at the core of the religious life of every convent led by spiritual directors, confessors and mother superiors. When writing about the nuns in their care in this period, spiritual directors made a clear distinction between pious lay women and those who had made the choice to leave the world and join a convent. The latter, they wrote, was the higher calling and required many specialized texts for spiritual direction. The ultimate aim of monastic life was perfect union with God. The distinction was expressed by many confessors in the period and highlighted by the Council of Trent. It is crystallized by an eighteenth-century spiritual director writing to a Carmelite novice at Hoogstraten:

Whatever you doo, forget not the end for which you enter’d into religion, which was not to become a vertuous devote, by strictly keeping the commandments, for this, as several others are, you might have been in the world; but you came to be made a holy religious, and to aspire to the heighest perfection, this life is capable of; which is to have your soul united after the strictest manner imaginable, in the state of grace with your God.Footnote 78

This view clearly separates the spiritual commitment of the nun from that of the devout lay woman and applies equally to the seventeenth as to the eighteenth century. It explains why so much emphasis in the convents was placed on creating texts that would assist the process of achieving a state of grace and becoming a true ‘Bride of Christ.’ The stakes were high.

Forming collections in the convents

A manuscript from the Paris Augustinian convent, from the latter part of the seventeenth century shows clearly that the anonymous author (a nun) understood the importance of spiritual reading to the community. She knew which authors were considered most beneficial to their spiritual lives, how texts should be read and how they should be applied in daily life. ‘Spiritual lectures are like laying up a provision for prayer, furnishing wood & fuel for that holy fire,’ she wrote.Footnote 79 Later she continues:

As to … spiritual books, those are to be preferr’d which instruct us in the principles & rules of a spiritual life, that explicate what it consists in, that teach the true means to attain to it; & amongst these, <p. 165> the Following of Christ, the Introduction to a Devout [Life], the Spiritual Combat, ought to have the first place; after these Grenado, Rodriguez, St Jure, Suffren, are much to be commended.Footnote 80 Others may be added according to the advice of our confessors, who being the best acquainted with the state of our consciences, can commonly judge best, what is most proper for us, for t’is certain, all good books are not proper for all sorts of persons souls, no more then all sorts of meat are for the body.Footnote 81

Here the author accepts the role of the confessor, with his years of training and education, in the selection of appropriate texts for her community. As we shall see, the influence of the confessor or spiritual director can be detected in every aspect of the creation of book collections; although we need to recognize, at the same time, the ways in which nuns were able to contribute additional material to their libraries.Footnote 82

Confessors and books

Male confessors and spiritual directors or advisors were in a position to exercise significant influence over the selection, acquisition and even the creation of texts for the book collections. The lengthy education of male religious and secular clergy gave them familiarity with the full range of texts currently available for the religious life in both Latin and the vernacular. In turn, their learning informed their teaching and spiritual direction of the nuns. The constitutions for Cambrai (1631) explain that the confessor (vicarius) ‘…shall have with him one or two Monkes of our congregation, of… sufficient learning and spirituallitie, that shall assist the-saied vicarious in saying or singing of Masse, in takeing the confessions of the Dames, and directing them in their devotions and exercises’.Footnote 83 Jesuits were not permitted by the order to become confessors in the convents; nevertheless they had a significant influence over conventual spirituality both in their role as spiritual directors and through their popular translations of devotional texts. Three examples may serve to illustrate aspects of the role of confessors and directors in seventeenth century convents in the creation of book collections: Augustine Baker at the Benedictine convent Cambrai; Thomas Carre at the Augustinian convent in Paris and Charles Dimock and other Bridgettine brothers at Lisbon.

The significance of Benedictine Augustine Baker, who was sent as spiritual adviser to the newly founded convent at Cambrai in 1624, and his influence on the convent’s book collections is well-known and needs only to be summarized here.Footnote 84 Baker developed his own particular approach to spiritual direction; basing it on the texts of medieval mystics such as Walter Hilton and Abbot Blosius, in contrast to the contemporary Jesuit texts used in other convents.Footnote 85 He advised on appropriate reading for the nuns in his care and inspired the Cambrai nuns to create thousands of manuscript pages to aid the spiritual development of those whom he directed in the community. As Heather Wolfe, Jenna Lay, Jaime Goodrich and others have argued, not only did Cambrai nuns copy Baker’s texts, they also compiled and edited them and thus created new versions. In addition many scribal copies were prepared to populate the library for the daughter house founded in Paris in 1651.Footnote 86 This creative culture resulted in the publication of two texts by women: the first printed edition of the works of Julian of Norwich (1670) edited by Serenus Cressy, Confessor in ParisFootnote 87 and Gertrude More’s Spiritual Exercises (1658), edited by Augustine Baker and Serenus Cressy. The latter was among the most widely found single texts in the libraries of the English convents.

Questions were raised about the orthodoxy of Baker’s teaching at Cambrai, and his methods were not favoured by the whole community: however the manuscripts were cleared of any heretical tendencies after examination in 1633 by the English Benedictine Congregation. Such was the commitment to Baker’s texts that when the president of the Congregation in 1655 ordered the surrender of the manuscripts to bring Cambrai into line with more conventional spiritual direction, abbess Catherine Gascoigne refused to obey.Footnote 88 By 1655 the manuscripts contained so much more than Baker’s words that labeling them as heretical, would in the abbess’ words, be ‘so great a prejudice to the books, and so great an injury to all such of the Congregation that do esteeme them’, she could not consent to hand them over.Footnote 89 This dispute indicates how convent leaders in extremis were prepared to take a stand against male authority and to exercise their own authority, derived from their constitutions, in choosing the most appropriate texts for their own libraries.

Thomas Carre (aka Miles Pinkney) a secular priest trained at Douay was involved with the Augustinian convent in Paris from its foundation in 1633 until his death in 1674. He became their chaplain and confessor while retaining a prominent role in the network of English secular clergy in France and with the French court, thus combining his spiritual role with practical advice on building and finance. Carre published sixteen books, most of them while he was at the convent. His first book printed in Paris in 1636 was an edition of the Augustinian rule and constitutions for the convent in English, followed rapidly by a series of translations of works by Thomas à Kempis found in most convent libraries. Carre has been described as a spiritual guide and interpreter rather than a theologian, basing his work primarily on the translation of key texts and adapting them for use in convents.Footnote 90 In these books Carre advertised his connection with the convent by including with his name as author, a version of the strap-line, ‘Confessour to the English Nunnes of Saint Augustines Order, Established at Paris’. His dedications moreover, drew attention to the nuns referring to them as ‘pious & obedient daughters’, of the Abbess Mary Tredway.Footnote 91 In Sweete thoughtes of Jesus and Marie he specifies that the text was written ‘for the use of the daughters of Sion,’ an indication that it was particularly suited for practical use by women religious. His writing clearly appealed to other English convents; multiple copies of his works can be found in many collections. A list of titles with convent associations is given below.Footnote 92 Carre’s significance to his own community and beyond is reflected in the sermon preached at his funeral by his successor Edward Lutton. In it he described Carre as having dedicated his life to the assistance and advantage of the community.Footnote 93 Lutton made particular reference to the nuns’

little Libraries, a great part whereof consists in the products of his pious learning: The Meditations which he hath compiled for your dayly mentall-prayer, and spirituall employment, for your Retreats, Cloathings, Professions and what not? The many Miscelaneous treatises, disputations, explications, and instructions: the severall works of the Devout and truly Religious Thomas of Kempis which he hath made yours, by making them intelligible to you. Nay he was not content to employ his Learning for the spirituall good of your House only, he farther engaged his pen for the honour and concerne of your whole Order…Footnote 94

The Bridgettines were part of a double house, one which included both men and women, until, that is, the last brother died in 1695.Footnote 95 The confessors at Lisbon were drawn from the Bridgettine brothers; they too provided the nuns with copies of important books.Footnote 96 For instance, Brothers John Vivian (p.1586–1624) and Stephen of the Conception Mease (p.1621–1662) were responsible for translating and copying ‘English Saintes of Kinges & Bishopps in the primitive times of the Catholique Church’.Footnote 97 This is a substantial two-volume leather-bound manuscript comprising more than 1000 pages, whose size suggests that it was copied for community reading in the nuns’ refectory. Mease commends the value of Vivian’s translation of the lives describing them as ‘most precious diamonds’ which can now be preserved for posterity now they are copied and bound. The book is one that links the exiled community with its English Catholic heritage.

Father Charles Dimock made his profession as a Bridgettine brother in 1619. He became the 14th Confessor General in 1647 and remained in post until his death in 1659. Like the two Bridgettine brothers noted above, he made translations for the nuns. For instance, in 1657, at the sisters’ request he translated from Latin the new rules they were instructed to adopt after settling at Lisbon.Footnote 98 A twentieth century notebook records a series of seventeenth and early eighteenth century manuscript translations from Lisbon of which three are described as being in the hand of Father Charles Dymock.Footnote 99 The first, dated 1654, translated from Spanish was ‘The booke of truth containing two hundred Dialogues’ by Peter of Medina.Footnote 100 The second; ‘Da tranquillidade da Vida’ dated 1627 is described as ‘A booke of S Jhon Justuo, Lanspergius, Carthusian upon the Birth, Life and passion and glorification of Our Lord…’Footnote 101 The third manuscript some several hundred pages long, is entitled; ‘The solitarie taulks of Thomas a Kempis, 1656’ and appears to be the ‘Soliloquies’ listed below. On the fly leaf of the second manuscript, Dimock listed 13 works as ‘Bookes of my own handwriting lent to the sisters,’ together with the names of the borrowers. They include a ‘Life of St Thomas of Canterburie’; ‘St Bernards Epistles with other works’; ‘St Bernards Epistles alone’, ‘The Soliloquies of Thomas a Kempis, with the Mysteries of the Christian faith of Titelman’ translated from Latin and copied in 1626. The latter which had been lent to Sister Mary Carnaby is inscribed ‘I intreate them that shall reade this my translation to amende the faults by oversight committed therein’, suggesting that Dimock was encouraging engagement on the part of his readers. One manuscript copy of ‘The Little Handbaskett or small basket with a present for the infant God’ is dated 1657, leather bound, quarto, with 310 pp. This is a Carmelite text for Advent which advised the nuns how to prepare for Christ’s coming and offerings they could make. Among the other manuscripts composed for the sisters are translations such as; ‘The life of the just in the practice of a lively faith, originally in Spanish translated into French’ inscribed on the title page ‘And now rendered into Inglish for the benefit of the Religious Sisters of Syon of the holy Order of St Bridgitt by Br Jerome of the most Bd Sacrament of the same Order. At Lisbo[n]… 1656.’Footnote 102 In Lisbon, as in England, the brothers had their own separate library which appears to have been sold when the last brother died: the manuscripts discussed here were clearly composed for the nuns.

Among other Confessors who contributed directly to the book collections in the English convents in this period, two others stand out. Father Richard Johnson at Louvain 1652–1687, who composed for the nuns in his care ‘four excellent books on Humility, Charity, Beatitude, and Veni Sancti Spiritus: besides a book of all sorts of directions and 16 volumes of sermons and two books of meditations.’ Father Edmund Bedingfeld confessor to the Carmelites at Lierre 1648–80, on his death bequeathed all his property to the nuns including his household stuff, his library and his plate.Footnote 103 Nicky Hallett points out that most unusually, Bedingfeld’s ‘Life’ was included with accounts of the nuns’ lives in the Lierre Annals, an indication of his importance to the community.Footnote 104

Jesuit Influence on convent book collections

Jesuits were widely influential in the English convents. They acted as spiritual directors to individuals or small groups of nuns and their books, including their many popular translations of devotional works, were in the convent libraries.Footnote 105 Among Jesuit texts frequently found are Henry More’s (c.1587–1661) translation of The happiness of the Religious State (1632) and Thomas Everard’s (1560–1633) translation of the Italian Jesuit Lucas Pinelli’s The mirror of religious perfection, 1618, which contains a dedication to Barbara Wiseman and her community in Lisbon. Books by the Spanish Jesuit, Alfonso Rodriguez appear in most convent libraries in English and French, among them A Treatise of Mentall Prayer (1627); A short and sure way to heaven (1630) and The practice of Christian perfection, published in London in 1697.Footnote 106 Tobie Matthew (1577–1655), closely associated with the Carmelites at Antwerp over several years, was responsible for several translations for English nuns.Footnote 107 His translation of Augustine’s Confessions, published in 1620 at St Omer, was owned by the Poor Clares. He undertook the translation of The Flaming Hart or the Life of the Glorious S Teresa (1642) for the Antwerp Carmelite community: a book found in many libraries.Footnote 108 Less well-known is The Penitent Bandido, 1620, which he translated for Lucy Knatchbull who was then at the Benedictine convent in Brussels. He later wrote her biography, a work which remained in manuscript until the twentieth century.Footnote 109

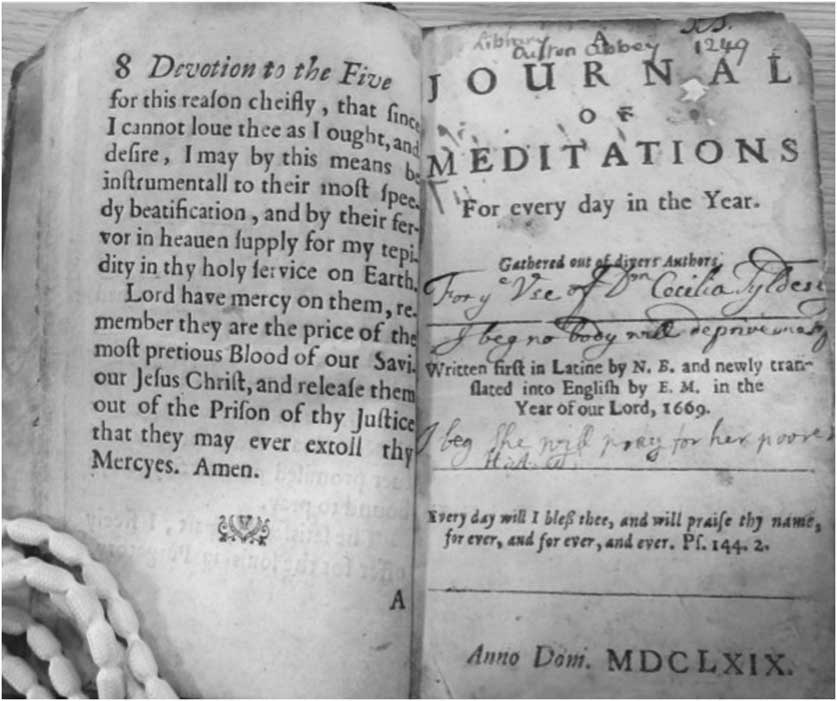

Figure 8 Title page in copy of Bacon’s A journal of meditations for every day in the year (1669) from the Benedictine library at Ghent showing inscriptions. Cecilia Tildesley, GB234 professed 1708? Reproduced with permission of Abbot Geoffrey Scott, Douay Abbey.

Nathaniel Bacon’s (1598–1676) A journal of meditations for every day in the year, published in many editions from 1669, was possibly the single most popular title among devotional works in the convents. For instance, the Benedictines at Cambrai had ten copies of the 1669 edition, as well as others. The translator, Edward Mico (c.1647–1678), explained in his preface that the original had been written in Latin for a community and had proved valuable ‘because the method is plain and easy to use’: as a result, copies had been made which led to publication in English for wider use.Footnote 110 The full Ignatian Spiritual Exercises were not translated into English until 1736 and required additional specialist texts and direction for convent use, although Bacon’s work could be used both within communities and by pious lay people for abbreviated exercises.Footnote 111

Exemplary lives provided inspirational reading for the Refectory or in cells. Here too, Jesuits provided appropriate books. The Lives (generally in English translations) of the Jesuits, St Ignatius, and St Francis Xavier appear in several collections.Footnote 112 A popular text across the English convents and among the laity was the life of Lady Warner (in religion Teresa Clare of Jesus) a wife and mother. She and her husband had agreed to separate so that they could both join religious orders. Lady Warner initially entered the Sepulchrines but decided to undertake the more austere life of the Poor Clares. Sir John (1628–92) became a Jesuit, taking the surname Clare. Both husband and wife were converts and they also had young children when the decision to become religious was taken, which added both to the poignancy and complexity of the situation. Written by the Jesuit Edward Scarisbrick (1639–1709), the account presents Lady Warner as a model of piety and devotion to God. The book was specifically credited with influencing Margaret Pye to leave Maryland and become a Carmelite in Antwerp.Footnote 113

Although it is possible to trace common themes and texts across the book collections of the English convents, it is important to remember the autonomy of each house, local influences, variations in daily practice of the Divine Office, different rules and strong individuals which all contribute to the range of selections made.

The involvement of convent members in book creation

The main focus of this paper has been on the printed books; however a significant element of the book collections were manuscripts generated within the convents. Part of the work of the choir nuns was to copy texts for their community and many others created individual compilations as part of their own spiritual development, some of which passed into common readership. Many nuns added substantially to community libraries in this way and by translating, or editing texts. In a few cases their work was published, but most survives only in manuscript.Footnote 114 Recent scholarship, including contributions to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, serves to illustrate the contribution made by writers such as Barbara Constable who left a body of thirty-one bound manuscripts for her community among which were at least eleven collections or compilations each averaging 600 pages. Sufficient manuscript pages survive to indicate a flourishing scribal production of texts for spiritual reading in many convents; indeed so many were produced at Cambrai that it was described as having its own scriptorium. At the present time there is a considerable amount of research and writing being undertaken with a number of monographs expected imminently, this short section can do no more than act as an introductory survey.Footnote 115

Key texts that were worked on as soon as convents had the capacity to do so were the Rule and the Constitutions. The enclosed convents followed the Benedictine, Augustinian or a version of the Franciscan rule. An English version of the Benedictine rule for women was published in 1513 but there is no evidence that the English convents in exile owned a copy: they appear to have worked from Latin versions. Tracing the process of translating the Benedictine rule at the first convent to be founded at Brussels, Jaime Goodrich demonstrates that the nuns were actively involved in the process of compiling the constitutions which when completed ‘we often and eagerly read, and if we found any doubtful, obscure, or difficult things, we noted each one with watchful care’.Footnote 116 Consultations with their confessor and a number of ‘learned men’ followed which finally resulted in print publication in 1632 with a text edited (rather than translated) by Alexia Grey with a number of other versions dating from the intervening years.Footnote 117 Victoria Van Hyning has identified a number of choir nuns at the Augustinian convents in Flanders who were ‘Latinate’: in other words they were able to translate Latin texts into English for their community. For instance Augustina Bedingfeld at Bruges translated the statutes so that they could be read to the community. Footnote 118 Alongside translations, the Benedictine Anne Cary provided a number of texts for her community: she worked with the confessor Peter Salvin to adapt the constitutions from Cambrai for the daughter house in Paris.Footnote 119 Securing publication of the constitutions served a number of purposes: it provided additional copies of a lengthy text widely used in the community without the burden of making scribal copies; it served to raise the profile of a particular convent and its version of the rule; and it enhanced their reputation as places of learning and observance.

Recent work on authorship and editing in the English convents has demonstrated that many texts were created communally and it is sometimes impossible to be precise about the nature of the contribution of a particular individual. As scribes it is possible to identify a hand: for instance Cecily Cornwallis at the Rouen Poor Clares wrote over many decades in a wonderfully clear, neat small rounded hand until her death.Footnote 120 However it is impossible to deduce from her manuscripts the extent to which she was involved in the creative writing and editorial process. The characteristics of modesty and humility often make it challenging to identify individual contributions to book collections, but their style and provenance mark many manuscripts as generated within the communities.

There would have been in most convents, nuns able to make competent translations of key texts. Although the language and culture of the convents was English, some convents, such as the Augustinians in Paris, and the Sepulchrines in Liège, went to some trouble to arrange for young entrants to spend time learning French before they professed. The linguistic skills of some English nuns can be seen in the description of Carmelite Margaret Mostyn’s simultaneous translations for the community,

… she would on fiesttiful days, and at other times; find out some pious historicall Booke; and read to ye religious … and yt was most admired, when it twas dutch of wch she had little knowledge, but by her one industry; and love of reading; she attained to such perfection in it; yt with only casting her eyes one ye Booke, she would deliver it word for word to ye Sisters in our naturall language; and this in so smoth a style, and with so great felicity … as it twas heven to heare her … for sayd thay though wee have often read, and heard, these very things before; coming from her Reverence it makes anothere manar of impression; for it seemes her words opens our understandings; and changes our very harts … (L3.29)Footnote 121

While the tone is that of a fond sister writing an obituary life, nevertheless it represents notable linguistic skills and the spiritual benefit that comes from understanding a text.

Among printed translations appearing in conventual libraries are three works by Elizabeth Evelinge who professed at the Poor Clares, Gravelines: The Admirable Life of the Holy Virgin S. Catharine of Bologna, The History of the Angellicall Virgin Glorious S. Clare and, either from Latin or French, The Declarations and Ordinances Made upon the Rule of our Holy Mother S. Clare: An Abridgement of Christian perfection, 1612, was translated by Benedictine foundress Mary Percy.Footnote 122 Many more texts remain to be published: for instance among manuscripts which served the community at the English convent in Bruges are two translations by Catherine Holland, ‘A Methode to converse with God’ translated from the French of Michel Boutauld 1683 and a translation from Dutch, ‘A Pleasant Treatise of the Illuminated Shepheard’.Footnote 123 As more research is carried out into conventual archives, it becomes possible to understand the extent of the contributions being made within the communities to their book collections. Many compilations made originally for personal use passed into the hands of others thus becoming part of the history and culture of the house.

Conclusions

Even this preliminary survey has been able to uncover enough evidence to show that book collections in the English convents in exile were significant. They were assembled over a long period of time from many sources in answer to the spiritual and practical needs of the members of the convents. It is vital to place alongside the printed works which have been the main focus of this study the considerable body of manuscripts which provided daily reading material and textual inspiration for many meditations. It is also important to set the convent libraries in the context of women’s learning across the religious divisions of the period. Not only were some book titles found in both Protestant and Catholic libraries, but a number of convent members grew up in households with more than a passing connection with members of another religious persuasion. Convent books like members of the convents were not isolated from the world: individual books and titles passed in both directions through that semi-permeable enclosure wall identified by historians of early modern convents.

Appendix

Selected printed books 1600–1700 from convent collections

The aim of this appendix is to give examples of a range of key printed texts from the seventeenth century found in convent libraries surviving either as books or as titles on lists. I have divided the books into seven broad subject categories: liturgical works including music mainly for use in the chapel, scripture and exegesis, devotional and instructional literature, including meditations, exemplary lives and martyrologies, church history, constitutions and rules; and a miscellaneous section which includes medical texts, herbals and occasionally secular works. The list is illustrative rather than comprehensive and titles have been included only where they occur in more than four libraries unless otherwise stated. The dates given are for editions occurring in the convents. Many of them are now available on EEBO.

The evidence shows that the main Catholic presses publishing books in convent collections were located at St Omer, Douai, Rheims, Rouen and Paris with a smaller number of books in English printed in Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp, Cambrai and, from the later part of the seventeenth century, London. The publishers served the wider market of the English Catholics in exile: male religious institutions as well as the laity.

Liturgical works

The Council of Trent ruled that all convents should use the Roman Missal for Mass. Even the Bridgettines accepted that they had to give up their own office after they went to Lisbon. Many editions of these texts exist in convent collections. Psalters might be used for spiritual reading and meditation as well as liturgically. Breviaries included all the texts needed for Divine Office. The Office for Holy Week was published separately and is found in most libraries in Latin, French and English editions. Throughout the Appendix bibliography, remove all brackets enclosing details of place and date of publication Retain square brackets where they occur.

Breviarum monasticum pro omnibus sub regula S.S.P. Benedicti … 1613, 1622, 1625, 1635 etc.

The generall rubriques of the Breviarie, put into English. Serving for the benefit of those, who desire to learne to say their Breviarie., St Omer, 1617.

Missale Romanum ex decreto sacrosancti Concilii Tridentini restitutum, … Antwerp, 1605, 1619, 1672, 1691, 1696 etc.

The office of holy week … Paris, 1605, 1631, 1670 etc.

L’office de la semaine saincte et de l’octave de Pasque en latin et en françois … Paris, 1659, 1670, 1672, 1684 etc.

Officium hebdomadae sanctae secundum missale et breviarum romanum, Antwerp, 1630, 1663 etc.

Pseaumes de David, traduction nouvelle selon l’hebreu et la vulgate… Paris, 1666, 1672, 1678 etc.

Psalterium Davidis, Antwerp, 1610, 1624, 1639, 1653, 1683 etc.

The office of the B. V. Mary in English: to which is added the vespers or even-song, in Latin and English… London, 1687, 1699.

The primer or office of the blessed Virgin Mary, Antwerp, 1685.

Scripture and Exegesis

The New Testament of Jesus Christ, translated faithfully into English, out of the authentical Latin, according to the best corrected copies of the same, diligently conferred with the Greeke and other editions in divers languages; with arguments of bookes and chapters, annotations, and other necessarie helpes, for the better understanding of the text, and specially for the discoverie of the corruptions of divers late translations, and for cleering the controversies in religion, of these daies: in the English College of Rhemes. Rheims, 1582.

Biblia Sacra vulgatae editionis, Plantin, 4 vols. Antwerp, 1629.

The Holie Bible faithfully translated into English, out of the authentical Latin. Diligently conferred with the Hebrew, Greeke, and other editions in divers languages. With arguments of the bookes, and chapters: annotations: tables: and other helpes, for better understanding of the text: for discoverie of corruptions in some late translations: and for clearing controversies in religion / By the English College of Doway. Douay, 1610, Rouen 1635.

Devotional and Spiritual Direction

This is by far the largest section in every library. Many of the texts included here were used as a basis of personal compilations and were widely influential. Predominant languages were English and French, although works in Latin and other languages do occur.

Blosius, L, A mirror for monks, Paris, 1676. Also in French

Augustine: The confessions of the incomparable doctour S. Augustine, translated into English. Togeather with a large preface, which it will much import to be read over first; that so the book it selfe may both profit, and please, the reader, more. [trans. Tobie Matthew] St Omer, 1620

Augustine, Aurelii Augustini hipponensis episcopi Confessium libri tredecim opera theologorum lovaniensiam ex manuscriptis codicibus multum emendati ejusdem Confessio theologica triparta. Coloniae Agrippinae, in officina Birkmanniae, sumptibus Arnoldi Mylii Cologne, 1604

Augustine, The meditations, soliloquia and manuall of the glorious doctor S. Augustine: translated into English [Carre] Paris 1631

Augustine, Les soliloques, le manuel, et les meditations de S. Augustin. Traduction nouvelle, reveue tres-exactement sur le Latin. Paris 1659, Brussels 1675

Nathaniel Bacon, SJ, A journal of meditations for every day in the year. Gathered out of divers authors. Written first in Latin by N. B. and newly translated into English by E[dward] M[ico]., [St Omer], 1669, 1674, London 1687.

Augustine Baker, OSB, Sancta Sophia: or Directions for the prayer of contemplations &c … methodically digested by the R. F. Serenus Cressy of the same order. Douay 1657—23 copies at Cambrai

Augustine Baker, OSB, The holy practises of a devine lover or the sainctly ideosts devotions, Paris, 1657

St Bridget, The most devout prayers of St. Brigit touching the most holy passion of Our Saviour Jesus Christ. Composed by the aforesaid Saint, by instinct of the Holy Ghost., Douai 1663, & 1668, Cambrai 1677, & 1683

Thomas Carre, Sweete thoughtes of Iesus and Marie, or, Meditations for all the feasts of our B. Saviour and his B. Mother togeither with Meditations for all the Sundayes of the yeare and our Saviours Passion: for the use of the daughters of Sion: divided into two partes/by Thomas Carre, Preist of the English Colledge of Doway. Paris 1658, 1665

Jean Crasset, SJ, Considerations sur les principales actions du chréstien, Liege, 1686

Luis de Granada, OP, A memorial of a Christian life. Wherein are treated all such thinges, as appertaine unto a Christian to doe, from the beginning of his conversion, untill the end of his perfection. Devided into seaven treatises: the particulers whereof are noted in the page following / Written first in the Spanish tongue, by the famous religious father, F. Lewis de Granada Prouinciall of the holy order of preachers in the Prouince of Portugall. [trans Richard Hopkins], St Omer 1612, 1625, 1688, 1699 etc.

Luis de Granada, OP, Of prayer and meditation: wherein are conteined fowertien devote meditations for the seven daies of the weeke. Rouen, 1584

Julian of Norwich, 16 Revelations of divine love shewed to a devout servant of our Lord called mother Juliana an anchorite of Norwich. Published by R. F. S Cressy, 1670

Thomas of Kempis his Soliloquies translated out of Latine by Thomas Carre confessour to the English Nunnes of Saint Augustines order, established at Paris, Paris, 1653, London 1673.

Thomas à Kempis, De imitatione Christi libri quatuor … Audemari, [St Omer] 1621, 1630.

Thomas à Kempis, The following of Christ in four books … St Omer 1612, Rouen 1652, London 1672, London 1673, Antwerp 1686.

Albertus Magnus, The paradise of the soul: or, A little treatise of vertues. Made by Albert the Great, Bishop of Ratisbon, who died in the year 1280. Translated out of Latin into English, by N. N. [trans. Thomas Everard, & dedicated to Mary Percy] St Omer 1618, London 1682

Gertrude More, OSB, The spiritual exercises of the most vertuous and religious D. Gertrude More, of the holy Order of S. Bennet and English Congregation of our Ladies of Comfort in Cambray…, Paris 1658.

More, Henry, trans. Hierome Plautus, The happiness of a religious state, Rouen, 1632.

Lucas Pinelli, SJ, The mirrour of religious perfection devided into foure bookes. / Written in Italian by the R. F. Lucas Pinelli, of the Society of Jesus. And translated into English by a Father of the same Society, St Omer, 1618.

Alfonso Rodriguez, SJ, A short and sure way to heauen, and present happiness. Taught in a treatise of our conformity with the will of God. Written by the Reverend Father Alfonsus Rodriguez of the Society of Iesus, in his worke intituled, the exercise of perfection and Christian virtue. Translated out of Spanish. St Omer, 1630. [Dedicated to Anne of the Ascension, Prioress of the English Teresians at Antwerp.]

Alfonso Rodriguez, SJ, The practice of Christian perfection written in Spanish by Rd. Father Alphonsus Rodriquez of the Society of Jesus. Translated into English out of the French copy of Mr. Regnier Des-Marais, of the Royal Academy of Paris, [trans. Sir John Warner—see Scarisbricke below] London, 1697, 1698, 1699. Also Pratique de la Perfection Chrestienne, Lyon 1683, 1693.

St Francis de Sales, OFM, Delicious entertainments of the soule written by the holy and most reverend lord Francis de Sales, bishop and prince of Geneva translated by a Dame of Our Ladies of Comfort of the order of S. Bennet in Cambrai. [Trans. Pudentiana Deacon OSB] Douay, 1632.

St Francis de Sales, A new edition of the introduction to a devout life: together with a summary of his life, and a collection of his choisest maxims…, [Douai or St Omer] 1622, 1669, London 1675, London 1686, 1695.

Robert Southwell, SJ, St Peters complaint and saint Mary Magdalens funerall theares with sundry other selected and devout poems, [St Omer], 1620

Exemplary Lives

These form a large section. They were intended for private reading and in the Refectory. MS Lives of members and founders were often used in addition to printed sources.

Dominic Bouhours, SJ, Life of St Ignatius … translated in to English by a person of quality [probably Mr John Dryden], London 1685, 1686

Dominic Bouhours, SJ, The Life of St Francis Xavier, [trans Mr Dryden] London, 1688

Catherine of Sienna, The life of the blessed virgin, Sainct Catharine of Siena: drawne out of all them that had written it from the beginning, and written in Italian … and now translated into Englishe … by John Fen … [Douai], 1609.

Nicolas Caussin, SJ, The holy court in five tomes … the fifth containing the lives of the most famous and illustrious courtiers; taken both out of the Old and New Testament, and other modern authors / Written in French by Nicholas Caussin, translated into English by Sr. T. H. [Thomas Hawkins] and others. Rouen 1634, London 1650, London 1663, London 1664, London 1678.

The Roman martyrologe according to the reformed calendar faithfully translated out of Latin into English, by G. K. [George Keynes the elder] of the Society of Jesus. [St Omer] 1627, St Omer 1667.

The English martyrologe: conteyning a summary of the liues of the glorious and renowned saintes of the three kingdomes, England, Scotland, and Ireland … VVherunto is annexed in the end a catalogue of those, who haue suffered death in England for defence of the Catholicke cause, since King Henry the 8. his breach with the Sea Apostolicke, vnto this day. By a Catholicke priest, [attrib. John Wilson], St Omer, 1608.

Edward Scarisbricke, SJ, The life of the Lady Warner of Parham in Suffolk, in religion call’d Sister Clare of Jesus … Written by a Catholic gentleman London 1691, 1692

Teresa of Avila, Vida de Santa Teresa de Jesus. ‘The second part of the life of the Holy Mother S. Teresa of Jesus: or, The history of her foundations, Written by herself. Whereunto are annexed her death; burial; and the miraculous incorruption, and fragrancy of her body. Together with her treatise of the manner of visiting the monasteries of discalced nuns., London, 1669, 1671, 1675.

Teresa of Avila, The Flaming Hart or the Life of the Glorious S. Teresa, Foundresse of the Reformation of the Order of the All-Immaculate Virgin-Mother, our B. Lady of Mount-Carmel, [trans. Tobie Matthew] Antwerp, 1642.

Alfonso de Villegas, OP, The liues of saints. [Flos sanctorum] Written in the Spanish by the R.F. Alfonso Villegas Dominickan. Translated out of Italian into English, and diligentlie compared with the Spanish. Whereunto are added the lives of sundrie other saints of the universall church. Extracted out of F. Ribadeneira, Surius, and other approved authors. [trans. William and Edward Kinsman] St Omer, 1623, Rouen, 1628, St Omer, 1630

Luke Wadding, OFM, The history of the angelicall virgin glorious S. Clare, dedicated to the Queens most excellent Maiesty. Extracted out of the R. F. Luke Wadding his annalls of the freer minors chiefly by Francis Hendricq and now donne into English, by Sister Magdalen Augustine, [Elizabeth Evelinge] of the holy order of the Poore Clares in Aire Douay, 1635

Church History

These texts were suitable for reading to the community either in the refectory or workroom.

Serenus Cressy, OSB, The church-history of Brittany from the beginning of Christianity to the Norman conquest under Roman governors. Brittish kings. The English-Saxon Heptarchy. The English-Saxon (and Danish) monarchy, … From all which is evidently demonstrated: that the present Roman-Catholick religion hath from the beginning, without interruption or change been professed in this our island, &c. By R. F. S. Cressy of the Holy Order of S. Benedict London, 1685

Flavius Josephus, The famous and memorable workes of Josephus, a man of much honour and learning among the Jewes. Faithfully translated out of the Latin, and French, by Tho. Lodge, Doctor in Physicke, London 1609, London 1632.Footnote 124

Constitutions and Rules

Each convent arranged the printing of their Constitutions: these were read both privately and in community and served a number of functions.

The rule of the great S. Augustin expounded by the Venerable Doctor Hugh of S. Victor Translated into French by the R. Father Charles de la Grange Canon Regular of S. Victor. And now publish’d in English for the use of the English Augustin nuns. Bruges 1697[?] Other versions Paris 1636, 1639.

Benedictines, Statutes compyled for the better observation of the holy rule of the most glorious father and patriarch S. Benedict, ed. Alexia Gray. Ghent, 1632

Benedictines, The rule of our holy father Saint Benedict translated in to English. Doway, 1700 [dedicated to Abbess Mary Caryll]

Poor Clares, The following collections or pious little treatises together with the Rule of S. Clare and declarations upon it, are printed for the use of the English Poor Clares in Ayre. Douay, 1684.

Poor Clares, The rule of the holy virgin S. Clare: together with the admirable life of S. Catharine of Bologna of the same order. … [Trans. Elizabeth Evelinge, Aire], St Omer 1621

Miscellaneous

Very few books of this category appear in more than a single convent. For the seventeenth century mostly, titles were either related to health care or dictionaries.

Medicinal experiments, or a collection of choice remedies, for the most part simple and easily prepared. By the honourable R. Boyle Esq Fellow of the Royal Society., London, 1692

Elizabeth Grey, countess of Kent, A choice manuall, or, Rare and select secrets in physick and chyrugery … , London 1654.

Dictionnaire francais-anglais, edition de 1632, un volume in quarto: [Pontoise]

Introduction to the Latin Tongue, 1662: [Dunkirk]