Sir Charles Lock Eastlake's ‘Haidée, a Greek Girl’ (Figure 1), painted in Rome in 1827, depicts the beautiful island-dwelling maiden from Lord Byron's unfinished epic poem Don Juan. A curator at the Tate Museum interprets the portrait as personifying ‘the philhellenic spirit of the times and a northerner's yearning for the warmth and freedom of the South or the exotic East. … a striking image of a Byronic type’.Footnote 1 Following the idealised, allegorical and neoclassical ‘Grand Manner’ aesthetic promoted by Sir Joshua Reynolds and his followers in the late eighteenth century, Eastlake's Haidée looks chiselled in stone.Footnote 2 Her nose, chin and cheekbones are angular and defined like those of a classical sculpture. Evidence of her ‘Hellenism’ is thus left to the ornately patterned robe, headwear and golden necklace. The background portrays a dimly lit landscape that gives no indication of where the female figure is seated, nor why. The painting is placeless – except, of course, for the placemaking function of the title. To my eye, Eastlake's ornate, stony Haidée – more sculpted than human, more archetype than individual – bears a remarkably close resemblance to another famously placeless portrait: Leonardo da Vinci's ‘Mona Lisa’.

Figure 1. Charles Lock Eastlake, ‘Haidée, a Greek Girl’ (1827), Tate Museum. (colour online)

Is Eastlake's ‘Haidée, a Greek Girl’ a copy, a generic historical trope aping neoclassical redheads painted by the Renaissance masters or by Eastlake's immediate predecessors at the Royal Academy? To what extent is she treated, either as a real-life model or as a literary character, as an exotic fetish-object, for men by men? Eastlake's ‘Haidée, a Greek Girl’, though not remarkable, is a telling example of early nineteenth-century archetypal portrait painting, in which wealthy female patrons had their faces superimposed onto the bodies of peasants, dancers, musicians and other exotic characters.

Twenty years after Eastlake displayed his Haidée, critics lauded Daniel François Esprit Auber's new opéra comique titled Haydée, ou le secret, which was premiered on 28 December 1847 in Paris's Salle Favart. Set in sixteenth-century Dalmatia (Act I), Admiral Lorédan prepares to set sail against the Turkish fleet. He appears troubled, a condition not helped by the untimely request of his enemy, Malipieri, for the hand of Rafaela, Lorédan's ward. Having refused Malipieri, Lorédan hurriedly pens and pockets a letter before going to bed. Meanwhile, Haydée, a captured Cypriot slave, noting her master Lorédan's agitation, vows to discover his secret and help, for she is in love with him. While asleep, Lorédan inadvertently discloses this secret to Malipieri while re-enacting it in a dream. He reveals that he won the fortune of Donato, a Venetian senator, by cheating at dice (a plot point borrowed from Mérimée's 1830 story La partie de tric-trac). Donato later commits suicide and Lorédan, remorseful, has since adopted his niece Rafaela, and has searched for Donato's missing son, to whom he has written a letter. Malipieri steals the letter to use as a weapon against his enemy. The next day (Act II), Lorédan's fleet defeats the Turks. Despite Malipieri's objections, Lorédan awards a captured ship to Andrea, a young sailor. Rafaela tells Haydée that she loves Andrea, and Haydée tries to persuade Lorédan to let them marry, to which Lorédan agrees. In Venice (Act III), Haydée finds that Cyprus is now part of the Venetian Republic. Though she is again free, she chooses to remain Lorédan's slave. (Her opening aria is the first time we learn that Haydée is of royal blood.) Lorédan, overcome with remorse, attempts to kill himself. Haydée intervenes, confesses her love for Lorédan, and proclaims that only death will separate her from him. When Malipieri threatens to reveal Lorédan's secret to the Senate, Haydée discloses her own ‘secret’ and offers herself in marriage to Malipieri in exchange for his silence. Lorédan denounces her offer, and Haydée threatens to kill herself with her dagger. In a subsequent duel, the sailor Andrea kills Malipieri. Lorédan, aware of Haydée's love, resolves to marry her.Footnote 3

Auber's opera was a lasting success in the nineteenth century, receiving 499 performances between its premiere and 1894. The newspaper Le charivari raved that Auber's Haydée ‘is certainly worthy of being placed in the top category of inspiration by this master of opéra comique’.Footnote 4 Auber's long-time collaborator Eugène Scribe supplied the libretto. Scribe's archetypal ‘well-made plays’ (pièces bien faites) had dominated Parisian playbills for years.Footnote 5 Edmond Viel complimented the story's tight construction and the librettist's ‘inexhaustible fund of scenic surprises’.Footnote 6 Scribe's story, Giacomo Meyerbeer noted, was surprisingly serious for an opéra comique, but ‘the dramatic dimension’ of Auber's music and orchestration ‘is most arresting, composed with aptness and skill’.Footnote 7 Indeed, there was a sense that the story and score, with its dramatic twists, turns and hints of local colour, swelled beyond the generic confines of opéra comique. La France musicale, noting its ‘amphibious’ generic characteristics, linked the work to the composer's earlier and much grander La muette de Portici.Footnote 8 Thus from the outset critics praised Haydée while also calling into question the work's blending of international and intertextual references, most notably Auber's deployment of the Italianate barcarolle rhythm and his use of a humming chorus inspired by the popular German singing style of Brummlieder.Footnote 9 This vocal technique, a style of singing bocca chiusa, would itself become a trope of statuesque musicality. Singers, stripped of the visual spectacle of the moving mouth, become sounding objects on stage. When considered amidst the web of visual and textual sources inspiring the Haydée libretto, it is clear that Scribe and Auber's heroine echoes that of Eastlake's painting: at once foreign and familiar, human and statuesque, novel and conventional.Footnote 10

The spelling of her name may vary, but a closer examination reveals that the Haydée persona haunts nineteenth-century European art, music and literature. This article extends the genealogy of the Haidée/Haydée character in both chronological directions. To do so is to uncover the ease with which nineteenth-century writers transplanted archetypal exotic characters from setting to setting. A relatively late instance is Verdi's Aida who resembles Auber's Haydée (three syllables, with the H silent) in more than name. Therefore, rather than begin with Aida, this article positions Verdi's titular heroine amidst a web of literary sources that preceded the opera. It advances a straightforward assertion: that the creators of Aida were aware of, and borrowed from, Auber's Haydée, a work that in turn recalls multiple literary and visual texts.

The Aida-type, as I call it, existed long before the team of Auguste Mariette, Temistocle Solera, Antonio Ghislanzoni, Camille Du Locle and Giuseppe Verdi ‘created’ her. My point of departure is that characters named ‘Aida’, ‘Haidée’, Haïdee’, ‘Haydée’ and variations thereof are linked not only orthographically but by uncannily consistent commonalities. I summarise them here, and I elaborate on these traits over the course of the article: a backstory featuring non-Western European origins; enslavement to a benevolent Western male warrior-type and a romantic saviour complex towards that type; a fourth-wall revelation (via a soliloquy or aria) that she is in fact of royal or aristocratic blood in her respective land of origin; a proclivity to be secretive, keep secrets and be told secrets; a connection to embodied musicality (via diegetic music-making, overt references to her musicality, bocca chiusa singing or close association of the character with a musical instrument); and male characters’ fixation with the phonetics and musicality of her name.Footnote 11

Also common to this character archetype is a preoccupation with death. Tombs, statues and pillars surround the Aida-type, which as I will argue suggest connections to the Pygmalion myth, another trope of nineteenth-century arts. Related to this fixation with tombs – a fixation that brings together Egyptian, Greek and Judeo-Christian conceptions of death – is the question of etymology. After all, the word ‘Aida’ is neither Egyptian nor Ethiopian nor Italian, but Greek: ‘Aida’, ‘Haydée’ and ‘Haidée’ all seem to derive from Hades (Haidēs, Haidēs or Aidēs), a word that refers to both the god of the underworld and the underworld itself.Footnote 12 Although Verdi's is the only one to die, the Aida-type exhibits an openness to dying a martyr out of love for her enslaver. Tombs, columns and statues not only function as morbid motifs of the Aida-type but also reassert the archetype's Greco-Roman roots.Footnote 13

The sustained interest in this pan-European exotic heroine is also evident in other nineteenth-century musical works beyond Auber's and Verdi's operas.Footnote 14 The composer Felicita Casella (born Félicie Lacombe) premiered her Portuguese-language opera Haydée (libretto by Luiz Felipe Leite) in Porto in 1849 and, in revised form, at Lisbon's Teatro Dona Maria (now the Teatro Nacional Dona Maria II) in 1853, where Casella performed the titular role. Later in the century, André Messager composed the Byronic cantata Don Juan et Haydée, a work that won him the attention of Auguste Vaucorbeil, the director of the Paris Opéra, who subsequently commissioned Messager's ballet Les deux pigeons in 1884, a work that cemented his career.Footnote 15 Edmond de Polignac also composed a cantata named ‘Don Juan et Haydée’.Footnote 16 Another operatic instance of the Aida-type extends the intertextual web beyond French and Italian sources: the four-act Czech opera Hedy by Zdeněk Fibich was premiered in 1896. Featuring a score redolent of Wagnerism and grand opéra tropes, Fibich's Hedy presents a version of the Byronic tale and noticeably adapts the spelling of the character's name to fit Czech pronunciation. The work was, unfortunately (but perhaps appropriately), written off as a pastiche of old styles. As one critic presciently reminisced, ‘women in the theatre shouted during intermission: “I would give ten Hedys for one Aida”.’Footnote 17

While this article makes a case for an unacknowledged connection between different operatic works, the broader aim is to emphasise the intersections of race, gender, geopolitics and genre in the construction of transmedial archetypes. I take ‘archetype’ to mean an abstraction constructed from repeated utterances, formulated in a scenario, template or character typology, then activated in a literary, visual or musical text.Footnote 18 Although one easily finds ‘exotic’ heroines, ‘slave girls’, ‘tragic mulattas’ and femmes fatales before and after the nineteenth century, I argue that this particular persona holds the key to understanding how Verdi's late opera was constructed from ready-made character archetypes and generically exotic scenarios that have hitherto gone unrecognised.Footnote 19 By following the Aida-type through works by Byron, Dumas, Auber and Verdi – and in a brief coda, into cyberspace – this article connects Verdi's heroine to a web of uncannily similar predecessors, revisits the arguments for and against the ‘authenticity’ of brownface, and explores how these debates around authenticity hold us back from understanding the more comprehensive, structural forms of alterity that informed the production and reception of the operatic archetypes.Footnote 20

The Aida empire

The substantial scholarship on Verdi's opera has almost unanimously taken the imperialist ‘realism’ of her representation as the point of departure. This reading, which informs Edward Said's famous study of the work, reveals how Verdi's Aida reflects the imperialist tendencies and ideologies of the European ‘West’ towards the non-European ‘East’.Footnote 21 The staying power of Said's critique is precisely due to this transcendence of modern-day geopolitics in a more abstract space of ideology. His notion of a structural, not geographic, East/West binary is in itself an archetypal approach. Writing about Enlightenment modes of racial classification, Said identifies four motifs – archetypes, if you will – that informed subsequent notions of structural Orientalism: expansion, historical confrontation, sympathy and classification.Footnote 22 In their quest for universals, Enlightenment thinkers such as Kant and Montesquieu ascribed morality to racial physiology. Such designations gained power when in the nineteenth century these classifications became what Said terms ‘archetypal figures’, such as ‘primitive man, giants, and heroes’.Footnote 23 Thus the social construct of race in the nineteenth-century West was a game of archetypal family resemblances, including but not limited to racial phenotype, morality and the social relations between the colonisers and those colonised.Footnote 24 These abstracted relations informed not only geopolitics but also the ways in which fictional characters were sketched in opera. Yet despite Said's own archetypal analysis of Orientalism, musicological studies of Aida predominantly take the literal Egypt/Ethiopia premise as the point of departure. As a result, the scholarship on Verdi's Aida – or perhaps more accurately, Said's Aida – has become an empire unto itself.

Semantically, Aida seems hidebound by the geopolitical notion of ‘empire’. In general, scholars of Aida debate the degree to which Egypt or Ethiopia is accurately presented, misrepresented, or not represented at all. While these questions remain as pertinent as ever, such studies hover around one another, critique one another, and revisit the readings of earlier critiques of the opera.Footnote 25 This focus on representations of imperial space on the operatic stage can obscure the ways in which exotic heroines were abstracted and recycled. Readings of the work take seriously the extent to which the opera reflected the expansion of colonialism during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In other words, cultural critiques of Aida begin with the opera's conception and then move forward chronologically to explore its reception and cultural resonance.Footnote 26 Christopher R. Gauthier and Jennifer McFarlane-Harris suggest that the work be read in the context of Egypt's own imperial and racial self-fashioning at the turn of the century. They conclude by advocating for a ‘flexible reading of Aida that takes seriously not only the position of the observer, but also the work that observers inevitably do in connecting the opera to their milieu’.Footnote 27 While Gauthier and McFarlane-Harris offer a localised, close reading of Aida as an index of Egyptian national identity, their chapter is a nuanced revision of ‘Said's Aida’ rather than an attempt to understand the intertextual contexts that led to the conception of the specific ‘Aida’ character in the first place. With such a focus on Verdi's intentions and the subsequent reactions of his critics, little attention has been paid to the non-Egyptian/Ethiopian contexts before Aida, leaving one to assume that this complex heroine was created ex nihilo.Footnote 28

What interests me is less an author's decision-making in context, but rather how a casual reader or operagoer may have absorbed archetypal characters from different theatrical and literary texts, or what Henry Jenkins would call transmedial storytelling.Footnote 29 A fictional character, when read archetypally, can expose the layers of identity that were folded atop one another. Ostensibly, Auber's Haydée, a white Cypriot, and Verdi's Aida, a Black Ethiopian, share little in terms of racial phenotype. Yet their common circumstances ring similar: disenfranchisement brought on by female slave-trade practices, geopolitical tensions that make certain royal and familial duties impossible, and an ability to code-switch and keep secrets, learned by necessity. Distinct in context, genre and racial phenotype, these two soprano heroines nevertheless both existed in fictional archetypal situations that did not allow for their voices to be heard on their own terms.Footnote 30

An archetypal approach by no means soft-pedals the politics of imperialism endemic to Verdi's opera, or, for that matter, to any of the aforementioned musical works. On the contrary, this shift in perspective away from work-centric exceptionalism to macro-level reading reveals the extent to which the nineteenth-century imagination reduced national origin and gender identity to a set of easily reproducible character traits. The Aida-type can be read as not having any nationality or ethnicity at all. Rather, an ambiguously named female slave/royal, chained to a vow of secrecy – for both romantic and geopolitical reasons – and driven by benevolence, engages in an archetypal master–slave dialectic with a male saviour-type who shares none of these characteristics.Footnote 31 Much as in commedia dell'arte, operatic titles and character names hold the keys to their typologies and origin stories. Such a computational approach to nineteenth-century character typology is less anachronistic than it may seem. This was, after all, the century of Scribe's pièce bien faite and Basevi's la solita forma, two ‘default settings’ of nineteenth-century French and Italian opera.Footnote 32

It was also the century of Lord Byron, an author who understood the rhetorical power of allegory and abstraction. Don Juan (1819–24) is ostensibly set in the tumult of late eighteenth-century geopolitics, but it is a set of blueprints for stock characters and scenarios. Alexandre Dumas's Le comte du Monte-Cristo (1844) features a character named Haydée, and Byron's Don Juan is namechecked in a discussion of this character's origins. It is therefore worth dwelling on these two literary works in more or less chronological fashion, not only because they feature characters named Haidée and Haydée, respectively, but also because elements of the ‘Byronic Hero’ are omnipresent in the ‘Aida-type’. The Aida character was not ‘made-up’, as some scholars claim, but rather ‘assembled’ through a conscious and unconscious accumulation of popular tropes and literary references to generic alterity.Footnote 33

Aida as Byronic heroine

Byron's unfinished Don Juan is part epic, part confessional. The protagonist Don Juan recounts his shipwreck, rejuvenation at the hands of Haidée and subsequent travels through the Mediterranean region – and he frequently interrupts these tales with digressions on alcohol, philosophy and criticism. Byron's poem can be read as an intertextual allegory, an autobiographical dream through which Byron – donning Juan's persona – has various amorous and near-death encounters. His characters are Byronic archetypes, copies of his own experiences, both real and imagined.Footnote 34

Haidée appears in Cantos II through IV. Midway through Canto II, Juan's ship is destroyed in a storm. A series of gruesome events follows: only a few crew members survive, and out of desperation they eat Don Juan's dog aboard their emergency dinghy. Still near starvation, the crew draws straws to see who will be cannibalised. Juan's servant Pedrillo is chosen. Those who eat the body go mad and drown themselves. Juan, now alone, eventually washes up on an island in the Aegean Sea. Not having eaten the corpse, he is near death from hunger, and passes out. Upon awakening, he finds two young girls staring at him. One keeps her distance but the other approaches. The reader gathers snippets of information about this mysterious girl through Juan's gradual return to health: ‘And slowly by his swimming eyes was seen / A lovely female face of seventeen.’Footnote 35 What Juan (and the reader) learns about Haidée is complicated by the fact that neither speaks the other's language. Their communication relies entirely on gesture, inflexion, superficial assumption and a few acquired phrases. Forty-eight consecutive lines are devoted to Haidée's appearance alone. It is likely that Haidée's painters consulted the following colourful description:

Byron's description is not devoid of exotic female stereotypes; we hear of her long, braided auburn hair and her stoic, statuesque visage. She is so charming as to be fake. Byron continues with an aside on neoclassical painting: he favours a more human, imperfect approach to portraiture:

Stoniness haunts the Aida-type. In his parenthetical aside, Byron speaks to nineteenth-century sensibilities when he notes that statues are a ‘race’ in themselves. In turning Haidée to stone, Byron conforms to what would become a century-long practice of reifying women's identities through the evocation of stone. At the same time, Byron's ‘race of imposters’, that is, statues, outlives their masters and serves new ones.Footnote 36 Each reincarnation of the Aida-type, then, has the unenviable – one might even call it Promethean – task of loving and redeeming her master, all the while performing a new, yet perpetually exotic, identity. The Byronic Haidée – based, as we have seen, on a real, Turkish slave – is truly a ‘stone ideal’, as all that is needed to activate her is an arbitrary change of nationality and a gentle respelling of her name.

Upon rescuing the beached Don Juan, Haidée and her servant Zoë hide him in a cave, lest Haidée's despotic father sell the white man into slavery. Haidée is fascinated by Juan, and he by her. In 1837, Alexandre-Marie Colin illustrated this scene in his ‘Byron as Don Juan and Haidée’ (Figure 2). Colin was receptive to Byron's vivid poetry: he included Don Juan's ‘clean shirt and very spacious Turkish breeches’ (garb that Haidée supplied), oysters (the ‘amatory food’ for Don Juan's nourishment) and, notably, Haidée's bare foot, following the contours of Byron's text ‘Her small snow feet had slippers, but no stocking.’ The bare foot is a recurring sexual motif that seems to suggest Haidée's cavalier attitude towards clothing; like the veil, the bare foot is what Bram Dijkstra would have called an ‘icon of misogyny’ – the addition of a sexually suggestive feature to a generic female character marked as non-Western.Footnote 37 Traditional signifiers of Haidée's ‘ethnicity’ are distinguishable only through her garments; she retains her distinctive golden jewellery that simultaneously establishes her class (as reported by Byron and painted by Eastlake, see Figure 1). Her skin tone is the same as Juan's, illuminated from a strong light source that seems to originate from within the cave. Henry Pickersgill's eerie illustration of Haidée for an 1837 printing of Byron's Don Juan (Figure 3) finds Haidée surrounded by the stone of what seems to be a room in a tower. Haidée looks longingly at the moon through a window, and yet she is the only lit object in the image. These images suggest that Haidée was far more than fodder for the sexual appetite for slave girls, nor was she merely a decorative piece of couleur locale. Rather, the Byronic Haidée is presented as a complex set of visual signifiers of royalty, enslavement and benevolence. A walking backstory, her origins, dignified behaviours and physical attributes would find their way into the pages of one of the most popular novels of the nineteenth century.

Figure 2. Alexandre-Marie Colin, ‘Byron as Don Juan, with Haidée’ (1837), Bridgeman Images. (colour online)

Figure 3. Henry William Pickersgill, frontispiece for Lord Byron, Don Juan: in Sixteen Cantos (Halifax, 1837).

Aida, Pygmalion and Monte-Cristo

If Don Juan produced a Byronic heroine in Haidée – caregiver, statuesque beauty, martyr – Haydée of Le comte de Monte-Cristo embodies a more powerful and active heroism. Dumas's Haydée is a polyglot and refined courtesan who helps the Count of Monte Cristo (born Edmond Dantès) inflict revenge upon Fernand Mondego – now Count de Morcerf, the man who was responsible for both Dantès's imprisonment and the death of Haydée's father.

Unlike her older cousin in Don Juan, Haydée in Le comte de Monte-Cristo plays an active role in the development of the entire novel. Briefly: she is the daughter of the Ottoman Ali Pasha of Tepelen, eventually bought by the Count of Monte Cristo from the Sultan Mahmoud. She is considered at once ‘Greek’, ‘Eastern’ and the daughter of an Albanian-Turk, causing several characters throughout the novel to comment on her ‘Hellenic’ elocution but also on her ‘Eastern’ mannerisms. Even though she was purchased as a slave, Monte Cristo treats her with the reverence of a free courtesan. With Dumas we have a stronger emphasis on the character's diegetic musicality, one of the ‘family resemblances’ of the Aida-type. Haydée attends local operas with the Count, and she entertains herself by playing an instrument that the other characters find unusual and striking.

As they did in Byron's Don Juan, male characters in Le comte de Monte-Cristo report on Haydée's physical features at various points in the novel. Two chapters – both titled ‘Haydée’ – are especially descriptive of the archetype. Haydée's jewels and her sculpture-like feet capture the attention of Monte Cristo. She wears a dress that displays feet ‘so exquisitely formed and so delicately fair, that they might well have been taken for Parian marble, had not the eye been undeceived by their constantly shifting in and out of the fairy-like slippers in which they were encased’.Footnote 38 By relating her feet to art objects and raw materials, her fictional observers create an intertextual link to another popular Greek trope of the era: the Pygmalion myth. Ellen Lockhart has explored the trope of the sentient statue in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. These literary Pygmalions, Lockhart explains, not only communicated in pantomime but also used ventriloquism. In this way, musicians, choreographers, scientists and philosophers conjured up statues in a range of discourses concerning ethnicity, enlightenment and consciousness.Footnote 39 We see these Pygmalionesque tendencies in Byron and Dumas, as well as in the painters who set their words in colour. Yet we also see them in Verdi's opera. As Aida descends to the tomb in Act III, she greets her ‘fatal stone’, as Lydia Goehr puts it, with a hymn of death: ‘O terra addio, addio, valle di pianti’.Footnote 40 In fact, contemporary critics noted that Aida seemed destined for a stony death from the beginning of the opera, anticipating what Gabriela Cruz has called Aida's inherent ‘subterranean morbidity’.Footnote 41 The critic Ernest Reyer, for instance, commented that Verdi had placed the ‘statue in the orchestra but left the pedestal on stage’.Footnote 42 In other words, Aida's accompanying music foreshadows the character's final tomb scene. This foreshadowing is particularly evident in Aida's ‘Ritorna vincitor’ (discussed later), which features quotes from the ominous chromatic melody in the opera's prelude. Yet to read ‘death’ into this character, to assume that ‘lateness’ in Verdi has brought upon a preoccupation with the end, is again to assume a rhetoric of realism – not to mention a Judeo-Christian perspective on the afterlife. As a Pygmalionesque figure, the Aida-type is laid to rest, only to be revitalised in a different setting and a different medium. Her death is a return to her stony origins, a cyclic completion of her trajectory as a statuesque archetype.

‘Celeste Haydée’

Just as the Pygmalionesque statues in Lockhart's book dance and sing their way into sentience, so does the Aida-type acquire agency through diegetic musicality. Even her appellation is musical: characters dwell on the exoticism of her name and explore its phonetic features at various points in Le comte de Monte-Cristo. We find these musical references in chapter 77, the second of the two chapters titled ‘Haydée’.Footnote 43 Morcerf, who is a guest in Monte Cristo's home (and does not recognise Monte Cristo as his nemesis) interrupts a conversation with his son Albert to listen against the wall, ‘through which sounds seemed to issue resembling those of a guitar’. Once Morcerf explains that the music is coming from Haydée's instrument – identified in the text as a guzla – Albert is struck not only by the sounds of this esoteric instrument but by the servant's very name: ‘Haydée! What an adorable name! Are there, then, really women who bear the name of Haydée anywhere but in Byron's poems?’ Morcerf proceeds to answer this bizarre intertextual question: ‘Certainly, there are. Haydée is a very uncommon name in France, but it is common enough in Albania and Epirus; it is as if you said, for example, Chastity, Modesty, Innocence,—it is a kind of baptismal name, as you Parisians call it.’ Perhaps there is something in the name, after all. Dumas assumes that Haydée's exotic name would register as exotic not only for the novel's characters but also for readers of the book: an exoticism that functions both diegetically and non-diegetically. The character Albert, in his shock, briefly becomes a post-structuralist; he can only make sense of her name by deferring to another text. The plot is thus interrupted to ruminate on the strange musicality of the name, as if Dumas had built the reader's own wandering thoughts into the narrative.

Like Albert in Le comte de Monte-Cristo, Radamès briefly pauses to ruminate on a slave's name. The three syllables of Aida's name form the melody of one of the most famous, and notoriously difficult, arias in the tenor repertory: ‘Celeste Aida’:

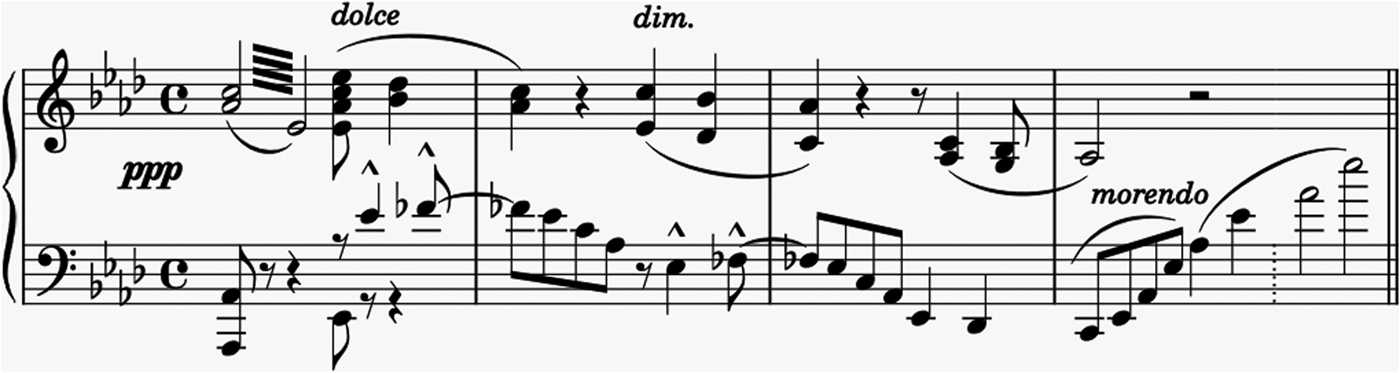

Few arias in the standard repertoire dwell on a character's name so prominently. ‘Celeste Aida’ forms part of Radamès's first soliloquy, following an expository recitative in which he identifies himself as an ambitious warrior. We learn of Aida being displaced from her homeland, but backstory is not the primary purpose of this romanza. Rather, it is an ode to her name. The first two words, connected through vowel elision, send the tenor voice soaring up an octave through his passaggio in a notably archaic example of operatic text painting (Example 1).

Example 1. Verdi, Aida, ‘Celeste Aida’, Act I scene 1.

As a slow-motion rhapsody that announces Aida's name and little else, ‘Celeste Aida’ brings the main plot to a halt, rupturing whatever Egyptian local colour had been established in the opening moments of the opera. Indeed, as Fabrizio Della Seta notes, Verdi and Ghislanzoni added the aria to Auguste Mariette's original scenario.Footnote 45 Given the amount of exchange between Verdi and Giulio Ricordi regarding the aria's punishing B flat, ‘Celeste Aida’ was not so much conceived for the fictional Radamès as for the very real tenors attempting the role.Footnote 46 Scholars have also commented on the abstract placelessness of the aria. For Julian Budden, this famous passage is nothing if not generic: Radamès's aria is a ‘typical instance of Verdian three-limbed melody fashioned into a French ternary design’.Footnote 47 Steven Huebner remarks on the conspicuous banality of the trumpet fanfare that announces the aria, an interrupting signal ‘so stiff and conventional’ that it is difficult not to hear ‘an undertone of irony or insincerity’.Footnote 48 This fanfare, and the romanza that follows, thus brings further attention to the sound of Aida's name. Verdi traces the three vowels up an octave in the key of B flat major, into a punishing tenor tessitura. Both male characters – Albert and Radamès – stop to focus on the phonetics of their respective Aida-type's name. In the novel, Dumas lists the name's various meanings and makes a non-sequitur reference to Byron; in the opera, Verdi uses ‘Celeste Aida’ to represent Aida's name musically. The trumpet fanfare that begins ‘Celeste Aida’ can thus be read not only as a signifier of Radamès's military background, but also as an announcement of a plot interruption. Pausing the story to enter Radamès's thoughts, we hear Aida's name ringing in his head. These transmedial interruptions, digressions and announcements amplify the Aida-type's capacity to be adapted from one artistic medium, ethnicity and plot to another.

Distant musicality

A key trait of the Aida-type is performative musicality. As we have seen, her name is the source of sonic fascination by the male characters who subjugate her. Yet unlike Byron's statuesque heroine, Dumas's Haydée is a literal musician. Her instrument – the guzla – is as exotic-sounding to the characters as her name. The guzla, or gusla, was a traditional one-stringed bowed instrument popular in Eastern European folk music-making in the nineteenth century.Footnote 49 The presence of the guzla in the story in turn refers to another French literary source: Prosper Mérimée's collection of faux-Greek poems titled La guzla, ou choix de poésies illyriques, recueillies dans la Dalmatie, la Bosnie, la Croatie et l'Herzégovine (The Guzla, or a Selection of Illyric Poems Collected in Dalmatia, Bosnia, Croatia and Herzegovina). They were published in 1827, the peak of French philhellenism and the year of Eastlake's ‘Haidée, a Greek Girl’. The specific details of how she makes or initiates music change from text to text, but these authors crafted the Aida-type to be as connected to exotic and overt performance as to saving her master/lover.

Haydée is already playing the guzla when the aforementioned scene (in chapter 77) begins. Throughout the novel, she seems instructed to play it when guests are nearby. An exchange in chapter 53 suggests that she plays the instrument often: Morcerf notes to Albert that ‘the poor exile [Haydée] frequently beguiles a weary hour in playing over to me the airs of her native land’.Footnote 50 Like the sound of Haydée's name, the timbre of the guzla is mysterious, charming and nostalgic; it performs the dual function of signifying Haydée's presence and indicating her foreignness.

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot's ‘Haydée, Young Woman in Greek Dress’, completed in 1872, shows a solitary girl with her instrument (Figure 4). Her dark eyes seem lost in thought, gazing into the bottom left corner of the canvas. Although she grips her instrument with two hands, she pays no attention to it. There is an intense perspectival duality, between the rock on which she sits and the ship in the background. The rock's edge in the upper left seems to carve out a separate canvas onto which the ship scene is painted. The rock is darkened by shadow, yet the light source, illuminating her gold garb, highlights most of her body. In short, Haydée looks disoriented, but her body also looks like it has been cut and pasted onto a rocky seascape. Corot's ‘Haydée’ bears a much closer resemblance to Eastlake's than to Colin's painting, in that the ominous background contrasts with the glowing presence of the sitting subject. Corot, unlike Eastlake, painted the whole body, and so Haydée's famed bare foot protrudes suggestively from beneath her dress, evoking the implied sexuality that both Byron and Dumas detailed in the works discussed earlier.Footnote 51 Her musicality, represented via the instrument as well as the performative sexuality expected of exotic female musicians, is thus a key signifier of the Aida-type's alterity.

Figure 4. Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, ‘Haydée, Young Woman in Greek Dress’ (1872), Musée du Louvre. (colour online)

The Aida-type represents distance, both geographic and temporal. Her exoticism is synonymous with the equally exotic musical instruments with which she is associated. Gabriela Cruz has written about instrumental diegetic musicality in the conception of Verdi's Aida, focusing not on the guzla but on the flute.Footnote 52 Occasionally found in sarcophagal remains, the flute has not only served as an access point into excavating the sensory experiences of everyday ancient Egyptians but also functioned as an evocative sonic symbol of ancient rites of passage for composers such as Mozart, Gluck and Berlioz. Yet as Cruz explains, composers preferred their imagined versions of the ancient world to those found in archaeological remains. Travelling to Florence to see an excavated Egyptian flute that François-Joseph Fétis had publicised in detail, Verdi left disappointed. Perhaps he had hoped to find an oracular instrument, but instead he bitterly described a ‘pipe with four holes like those our shepherds have’.Footnote 53 Verdi's Egyptomanic expectations were dulled by the unimpressive realities of the ancient civilisation's everyday objects. We can relate to Verdi's disappointment. Film and video game franchises such as The Mummy and Assassin's Creed romanticise Egyptian artefacts, but excavation and research can never match that bloated box-office standard; recently, scientists painstakingly engineered a 3D-printed voice box based on the cadaver of the 3,000-year-old Egyptian priest Nesyamun, only to generate an anticlimactic (yet hilariously adorable) chirp.Footnote 54 While Cruz dwells on the first part of Verdi's description – the ‘pipe with four holes’ – what interests me is the comparison with present-day rural flutes. Here, Verdi seems to equate an ancient Egyptian artefact with a contemporary Italian one. Although, as Cruz explains, Verdi would explore the flute's potential to signify Aida in his score – becoming something like her prosthetic voice – the casual conflation of now/then, East/West informed the ways that Aida was assembled from earlier artefacts, tropes and sounds, most of which had nothing to do with Egypt or Ethiopia at all. As we will see, the Aida-type's statuesque features, her musicality (both diegetic and nondiegetic), her rhapsodic name and her ability to musically encode secrets coalesced in a much earlier operatic character who, though not Ethiopian, nevertheless resembles Verdi's heroine in ways that can no longer be overlooked.

The Aida-type's secrets

The Aida-type seems perpetually sworn to secrecy. In Auber's opera, this facet of the archetype is on full display in Act I scene 4, in which the villain Malipieri demands to learn more about his rival, Lorédan. Here, it is revealed that Haydée may be more than a mere slave (one of the ‘secrets’ of Haydée, ou le secret). In the preceding scene, the secondary character Domenico discloses that Haydée escaped a massacre in her native Cyprus, was enslaved by Malipieri and was subsequently bought by the more benevolent Lorédan. This backstory, as Karin Pendle has noted, coincides with Dumas's nearly concurrent novel, in which the benevolent Monte Cristo brings Haydée into a better life, albeit still one of slavery. Furthermore, both Dumas's and Scribe's Haydées wear the distinctly exotic jewellery worthy enough for men of high social standing to comment on. Thus, Malipieri's deduction about his former slave's royal roots is an accurate one: ‘And so, from the diamonds that you wore and which my soldiers had taken from you, I have always thought, despite your obstinate silence, that you were connected with some rich and powerful family of Cyprus, that would someday pay for your ransom four or fivefold!’Footnote 55

While making this observation (and sharing expository information with the viewer), Malipieri is trying to wrest from Haydée the opera's main secret: Lorédan's cheating at dice, which led to a friend's bankruptcy and suicide. Malipieri interrogates her about what Lorédan says to her in their evening talks. But Haydée sings. She ‘sings’, in the sense that she lies to him, waxing poetic about how patriotic and loyal her master is to his country. In a lilting aria full of subtext, she teases Malipieri that Lorédan whispered to her to ‘be silent’. She is, of course, doing just that: resisting Malipieri's questioning, she ‘sings’ while not disclosing anything to him. Her response to Malipieri takes the form of a diegetic song in two couplets. Even in the context of opéra comique, in which actual speaking is juxtaposed with singing couplets, her concluding remarks to Malipieri seem cut and pasted, offering little contextual detail about what is happening in the story. The strange dislocation of this music is underscored by its diegetic nature. It is one of several points at which Haydée interrupts the plot to sing or to play an instrument: ‘C'est la ville aux joyeux ébats, / Chantez-y? Mais n'y parlez pas!’ (It is the city of joyous frolics, sing there? But do not speak!). At this point, Haydée's melody is now ornamented and faster, reminding the listener that her song is framed as a musical break from the story. Featuring melismatic vocalisation and repetition, her song conforms to broader tropes of diegetic songs-within-operas by exotic female characters, such as Sélika's Act II cradle song (‘Sur mes genoux, fils du soleil’) in Meyerbeer's L'Africaine and Lakmé's Act II ‘bell song’ (‘Où va la jeune Hindoue’) in Delibes's Lakmé.

Auber's Haydée ‘sings’ on several other occasions during the opera, including once with an instrument in hand. Later in Act I, Domenico notices that Lorédan is troubled, having just completed a letter that will decide Rafaela's future. Domenico attempts to appease Lorédan first by handing him a Turkish pipe, then by beseeching Haydée to ‘sing him some of those airs which do him so much good!’. According to the libretto, Domenico then hands Haydée a mandolin. She is joined by Rafaela, and the two women sing a barcarolle – but in this context it is a berceuse, as the intention is to lull Lorédan to sleep. Haydée not only sings but also does so on command and with skill.Footnote 56

The scene that most anticipates the plight of Verdi's Aida must be the opening of Act III. Back in Venice, Haydée, Lorédan and his entourage have returned from a successful naval battle in Act II. According to the staging instructions in the libretto, marble columns frame the proscenium, and the background shows the sea and Venice's main buildings. Haydée enters the Venetian palace alone. The columns serve not only as pillars but also as monumental reminders: of the Doge's power, of Venice's legendary serenity – and of Haydée's burdens, secrets and grief over her conquered family. As we learn in her opening recitative, these columns also signify death:

It was the Venetian army, after all, that had captured her from her native Cyprus, killed her family, pillaged her material wealth and deprived her of her royal power. At the same time, the palace is ‘his house’: she is, in a way, in the home of the man she loves. For the first time in the opera, Haydée confronts the master–slave dialectic. Although she has learned that she has been granted her freedom, she cannot leave Lorédan. She loves him, and although the extent to which he loves her is unclear – he never sings a ‘Celeste Aida’ – he requires her to nurture him as he agonises over his fate. Haydée's aria, ‘Pour punir pareille offense’, is her most serious moment in the opera, and the one for which the soprano will receive the most applause. The binary-form aria features two extended couplets, each of which can be subdivided into four distinct musical topoi: a cantabile, a waltz, a transitional stretta and melismatic vocalisation. These topoi not only constitute a compendium of Franco-Italian lyric conventions, but also conveniently map the archetypal sensibilities of the character.Footnote 57 Of note is the aria's dual key: beginning in F and ending in A flat, this third relation provides a dramatic pivot for Haydée's shifting thought processes. As she begins to sing, the F major melody of her opening cantabile seems to contradict her dreams of vengeance and retribution for the wrongs inflicted on her family (Example 2): ‘Pour punir pareille offense, / Tant d'affronts, tant de souffrance, / Dès longtemps à la vengeance / J'aurais dû, dans ma fureur, / Livrer mon cœur’ (‘To punish such an offence, so many affronts, so much suffering, I have longed for vengeance I should have, in my fury, surrendered my heart’).

Example 2. Auber, Haydée, ou le secret, ‘Pour punir pareille offense’, Act III scene 1.

There is conspicuously little ‘fury’ to her F major melody, and the contrast between melody and text makes this proclamation of vengeance hard to take seriously. Following a cadence on the dominant chord C is another pivot: the C is repeated in the orchestra and transforms into a waltz in A flat major. Having apparently forgotten about the gravity of her circumstances, Haydée turns on her heel to sing a coquettish tune about her secret crush whose name she dares not speak: ‘Ce nom, mon seul bonheur, / C'est celui du vainqueur’ (‘His name, my only happiness, is that of my conqueror’). A cadence initiates the third musical topos, a tense sequence of stepwise, ascending motives, during which Haydée synthesises her defensiveness over Lorédan's political reputation with her personal bond to him. In the coda that follows the second couplet, Haydée launches into a waltzing vocalise. Haydée the lovelorn queen becomes, once again, Haydée the exotic soprano (Example 3). Her wordless vocalising is consistent with her persona in Act I: lilting, carefree, eager to entertain, she resigns herself to Lorédan's fate, despite being free of enslavement.Footnote 58 Though never dipping into exotic couleur locale, these four musical topoi illustrate Haydée in a way similar to that of Eastlake, Corot and other painters: as ornate, reverential, musical and statuesque.

Example 3. Auber, Haydée, ou le secret, ‘Pour punir pareille offense’, Act III scene 1.

Although she never vocalises on a neutral vowel as Haydée does, Verdi's Aida discloses her diplomatic tendencies, social awareness and romantic co-dependency in her Act I aria ‘Ritorna vincitor’. Like Haydée, Aida stands alone surrounded by columns. Yet unlike Haydée, Aida is not automatically redeemed by the opéra comique convention of a happy ending. As Lydia Goehr and others have observed, Aida seems aware of her inevitable death and bears this burden from the beginning of the opera.Footnote 59 Aida's through-composed music is ostensibly richer in sonic content, but in terms of context, ‘Ritorna vincitor’ is the analogue to ‘Pour punir pareille offense’. She feels torn between obligations to her family, her country and her lover/enslaver, Radamès:

Aida's music, though not bound to conventional musical topoi, nonetheless shifts in character when Aida slides from thoughts of vengeance to love for her oppressor. This aria, like Haydée's, does not begin and end in the same key. When mentioning her enslaved father, Aida's recitative is accompanied by aggressive, chromatic passagework in the strings, whose pulsing diminished chords push the soprano higher in register (Example 4). Yet by the end of the aria, Aida resides in a lower tessitura in the key of A flat major – coincidentally, the same key that concludes Haydée's aria – and the aggressive violins give way to placid celli that conclude the number. Aida's music is like la solita forma in reverse, starting strong and ending soft. Verdi even writes ‘cantabile’ as the expressive marking for Aida's final, lyrical passage to the afterlife (Example 5).

Example 4. Verdi, Aida, ‘Ritorna vincitor’, Act I scene 1.

Example 5. Verdi, Aida, ‘Ritorna vincitor’, Act I scene 1.

This morbid foreshadowing is not prophesy. Read intertextually, Aida has been here before. Haydée's own frenetic aria, balancing duty, secrecy, romantic attachment and the spectre of death, created the template for a soprano slave–royal caught between a rock and a hard place. Surrounded by marble, both characters contemplate the tomb. Yet while one's life is spared by operatic convention, the other slowly expires in a long, final-act number, as so many operatic heroines do.

The Aida-type and the brownface question

This article has argued that the Aida character constructed by Mariette, du Locle, Solera, Ghislanzoni and Verdi was not their invention, but rather an archetype derived from sources earlier in the nineteenth century, notably the opéra comique Haydée, ou le secret. With roots in Greek mythology, the Haydée character created by Scribe and Auber was, in turn, a compilation of mythological, exotic and historical tropes. Although no documentary evidence directly attributes the conception of Verdi's Aida to Auber's Haydée, the two characters share an uncanny set of family resemblances which, when read intertextually, reveal that Aida's ‘African’ setting was perhaps more inspired by generic, timeless notions of alterity than has previously been thought.

The Aida-type does not feign authenticity. It is an intertextual infrastructure built around common tropes: enslavement, anachronism represented by references to Greco-Roman statues, sexually motivated saviour complexes, embodied musicality and forced secret-keeping. These tropes in turn domesticate and naturalise otherness, making it possible to present it matter-of-factly as exotic art.Footnote 61 An example of this disregard for authenticity of representation exists in plain view in an 1870 letter from Auguste Mariette to Camille du Locle: ‘Don't take fright at the title. Aida is an Egyptian name. By rights, it should be Aita. But the name would be too harsh, and the singers would inevitably soften it into Aida. Anyway, I don't set much store by that name more than any other.’Footnote 62 It is precisely this cavalier approach to dramaturgical detail that underscored the structural racism pervasive in nineteenth-century operatic conventions. The exoticism of these operas rested not only on what they evoked (i.e., couleur locale) but also on the protagonist's broader social circumstances, how she navigates them and how her (male) interlocutors navigate her. One scholar who – perhaps unintentionally – explored Aida's alterity by deliberating trying to look past it is Julien Budden, who commented that the Aida plot ‘is an old-fashioned and generic one and a surprising choice for Verdi’.Footnote 63 The word ‘generic’ here has more meaning that Budden had perhaps intended. Budden was an apologist for the work's aesthetic autonomy, citing ‘a complete absence of racialist … overtones’ in the work.Footnote 64 In his usage, ‘generic’ was a marker of innocence: by this logic, only serious, realistic works can be seriously racist. Yet by reframing Aida as ‘generic’, we are better equipped to understand the network of tropes, templates, archetypes and stereotypes available to opera's producers and legible to opera's viewers. Karen Henson has interpreted Aida along such lines, showing how the opera's most iconic scenes could easily be cut and pasted into earlier works depicting what Said would call the ‘East’, such as Meyerbeer's L'Africaine and Massenet's Le roi de Lahore and Hérodiade. Footnote 65 Yet an even more abstracted approach that looks beyond the concept of the nation-state, like the one I have proposed, links Verdi's heroine to an even richer tapestry of texts that extends beyond grand opéra. This approach skims the surface of numerous works without needing to dig into the personal inclinations of their authors. Historicist readings have a lot to offer in terms of unpacking the politics of representation, but they also reify the fictionalised ‘Africanness’ of the opera in the process. The fact is that Aida remains in the European operatic canon, and canons – like other hegemonic structures – presume colour-blindness and universality while re-enforcing structures of normativity. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the question of brownface in traditional (non-‘Regietheater’) productions of Aida, and subsequent defences of so-called ‘authentic’ staging by white performers, critics, directors and administrators, remains controversial in stalwart American institutions such as the Metropolitan Opera.Footnote 66

In June 2019, the American classical musical periodical VAN magazine reported on an Instagram post by the superstar soprano Anna Netrebko.Footnote 67 Gazing up at her phone while catching her reflection in the mirror, Netrebko appears in full operatic costume, wearing a gold tiara, red cloak, ornate jewellery and brownface makeup covering her face, neck and exposed shoulder. In response to the deluge of both critical and defensive comments, Netrebko replied, ‘Black Face and Black Body for Ethiopien [sic] princess, for Verdi['s] greatest opera! YES!’ This Instagram post – and the onslaught of discourse that has reenergised the controversy around Aida's brownface for the better part of the #BlackLivesMatter era – raises significant questions about how Aida's supposed ‘Africanness’ has been weaponised by brownface's defenders.Footnote 68 Olivia Giovetti's VAN article quotes musicologists Imani Mosley and Naomi André, who both remind the reader of the real stakes of these allegedly fictional representations. As Mosley argues, the question is not just whether black/brownfaced characters appear as villains in their respective fictional worlds: ‘it's an issue that has real repercussions and real ramifications, even if it's nice-looking and not perpetuating of derogatory black stereotypes’.Footnote 69

Just as the notion of ‘race’ is a social construct in which phenotypes, social relations and material conditions are in a perpetual process of negotiation, so too are operatic archetypes reflective of racial, gendered and socioeconomic conditions. According to the cast notes in Giulio Ricordi's production book for La Scala, the actors playing Aida and Amonasro should be darkened with makeup; they should have ‘olive, dark reddish skin’ onstage.Footnote 70 Yet there is slim evidence that singers in the nineteenth century consistently coloured their faces. This was perhaps due to the conditions of visibility and shadow in gaslit theatres, or perhaps to black/brownface being reserved for villainous, comic or peripheral characters as opposed to titular heroes and heroines.Footnote 71 In an 1865 illustration of the protagonists in Meyerbeer's L'Africaine, the eponymous Sélika (soprano Marie Saxe in costume) looks nearly identical to her white Portuguese rival Inès (soprano Marie Battu), while Sélika's brother Nélusko (baritone Jean-Baptiste Faure) is visibly darkened (Figure 5). In short, racial alterity in the nineteenth century was represented by a more generic array of tropes, allegories and signifiers than it is in modern-day ‘authentic’ productions.Footnote 72 Yet despite the lack of evidence that nineteenth-century opera heroes and heroines consistently performed in brownface, major opera institutions and performers continue to utilise anachronistic and skin-deep visual stereotypes in the name of faithfulness to what the creators intended.Footnote 73

Figure 5. Principal singers in costume for the premiere of Meyerbeer's L'Africaine. Le monde illustré (6 May 1865). (colour online)

The Aida-type unsettles these pervasive and often superficial binaries of self/other, real/fictional and East/West. It exposes a network of placeless and lifeless tropes, created for and by the nineteenth-century reader and spectator. It shows that these various family resemblances involved both a cavalier attitude towards ethnic origins and an enactment of a sexualised female slave fantasy. I close with what can be considered an updated version of the Aida-type: a recent example of how archetypes of alterity dating from the nineteenth century persist in virtual spaces.

coda_aida.exe

In 2016, independent video game developer Haydee Interactive released Haydee (no accent), a third-person shooter, on the PC platform. Available for sale via the online market Steam, Haydee features a half-human half-robot who navigates an abstract warehouse environment, collects inventory, solves in-game puzzles and battles robots.Footnote 74 There is no context or backstory. A fan site discloses that cyborg Haydee's name indeed derives from Le comte de Monte-Cristo, and that it is a Greek word for ‘well behaved’.Footnote 75 Yet this information has no bearing whatsoever on the game. No cut-scenes or dialogue introduce the player to the character or the scenario. There is no soundtrack to set the atmosphere. Any information about the character is gleaned from her appearance, and the degree to which the developers were preoccupied with hypersexualising the character is evident. Sporting heels, Haydee moves with an exaggerated swagger. Her world is a warehouse, but because the game is a third-person shooter, it doubles as a tomb.Footnote 76 Voiceless and faceless, she cannot speak but does not need to, as there is no dialogue in the game. She instead gains agency through her sophisticated abilities to navigate tight spaces and destroy enemies. At the beginning of the game, we learn that this modified human female is a copy; in a revealing screenshot (Figure 6), she emerges from a row of deactivated Haydees, all with identical proportions, brown complexion and metallic helmet. Haydee is a cyborg, an abstraction, an archetype of a hypersexualised robot-warrior of unknown origin who reboots as soon as she dies. Given Haydee's independent, low-budget release, it is assumed that seasoned gamers would likely recognise the tropes, scenarios and goals of similar video games – much like seasoned operagoers who are intimately familiar with convention and tradition and who know what is expected of them as spectators. The cyborg Haydee's existence is predicated on a balance of abstraction and expectation.Footnote 77

Figure 6. A row of deactivated Haydees. Screen capture by Jacek Blaszkiewicz, 21 September 2021. (colour online)

My intention in this brief coda is to address why operatic archetypes continue to be reproduced in different iterations, as human and – evidently – as cyborg. Donna Haraway defines a cyborg as a ‘hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction’, and underlines that ‘Social reality is lived social relations, our most important political construction, a world-changing fiction.’Footnote 78 Haraway's work has endeavoured not only to disrupt the binaries between human/animal and human/machine but also to critique the Western literary tradition of male domination over the non-male. The debates about Aida's intersectional crises – debates legible in academic and journalistic writing, the opera industry and social media – often assume that the racial, geopolitical and gendered circumstances of this fictional character were invented by her authors. The cyborg version of Haydee offers yet another example that gendered exotic archetypes are necessarily generic, ambiguous and rebootable. Of course, scholars in visual and media studies have long interrogated racialised and gendered stereotypes in video games. Leman Giresunlu has argued that the use of godly female imagery in video game franchises such as Resident Evil, especially imagery linking female bodies with machines, builds on a long-standing practice in lore, mythology and literature featuring names with feminine qualities.Footnote 79 Despite the burgeoning scholarship on the subject of ‘ludomusicology’, more work remains to be done on the translation of operatic archetypes into the virtual worlds of games: not merely the presence of operatic sound per se, but also the influences of operatic production on game design.Footnote 80

Deprived of a concrete origin story, hypersexualised, and unafraid of death, the cyborg Haydee can thus be read as a reboot of her nineteenth-century stock character predecessors. As Haraway writes, ‘cyborgs are not reverent; they do not remember the cosmos. They are wary of holism, but needy for connection.’Footnote 81 Granted, Cyborg Haydee is not forced to love or to die. Yet on the other hand, she is literally controlled by a user's keyboard and mouse inputs – and the game being fiendishly difficult, Haydee ‘dies’ often. She has multiple lives and multiple versions, and she does not carry scars, secrets or memories. The screenshot of her standing among her replicas is a potent metaphor for the archetype first imagined by Byron and expanded on through the nineteenth century. Auber's Haydée and Verdi's Aida, therefore, were not created as much as activated. I close with Haraway, whose framework offers a hermeneutic way out of the dualisms that tie the Aida-type to ethnicity, empire, gender, performativity and death. Like archetypes, cyborgs are treated like ‘illegitimate offspring’, more beholden to their current masters than to a single provenance: ‘but illegitimate offspring are often exceedingly unfaithful to their origins. Their fathers, after all, are inessential.’Footnote 82

Acknowledgements

For their invaluable feedback on this article, I would like to thank Annelies Andries, Matthieu Cailliez, Gabrielle Cornish, Sarah Hibberd, Iliya Mirochnik, Megan Sarno, Megan Steigerwald-Ille and the two anonymous reviewers. Special thanks to Ralph P. Locke, who encouraged this project from its earliest stages.