Introduction

In 1994, a cemetery was discovered on the western slope of the Lower Agora of Sagalassos (Waelkens et al., Reference Waelkens, Vermeersch, Paulissen, Owens, Arıkan, Martens, Waelkens and Poblome1997: 205–14), a city in the ancient region of Pisidia (south-western Anatolia). Further excavations, through to 2008, revealed that this graveyard extended to the east and south of the former temple of Apollo Klarios, situated on the hill overlooking the Lower Agora to the east (Waelkens et al., Reference Waelkens, Poblome, Paulissen, Talloen, Van Den Bergh, Vanderginst, Waelkens and Loots2000: 362–84; Ricaut & Waelkens, Reference Ricaut and Waelkens2008: 535–64). This Ionic peripteral temple, dating to the last decades of the first century bc, was converted into a tripartite transept basilica in the late fifth to early sixth century ad (Talloen & Vercauteren, Reference Talloen, Vercauteren, Lavan and Mulryan2011: 368–70). The Christian basilica was damaged in a seventh-century earthquake and possibly abandoned for some time, as were other parts of the former city, when the nucleus of the settlement shifted to the south. There, the temenos of the former sanctuary of the imperial cult became the centre of a new fortified settlement or kastron (Poblome et al., Reference Poblome, Talloen, Kaptijn and Niewöhner2017). By at least the eleventh century, the religious function of the Apollo Klarios site was restored, when a smaller structure, possibly a chapel, was built within the shell of the former basilica. This date is given by several anonymous eleventh-century folles (Byzantine bronze coins) which were retrieved from the floor level of tamped earth and its substrate inside the transept of the former church (Talloen, Reference Talloen2007: 327–30) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Plan of the eleventh-century phase of the funerary chapel, showing the Middle Byzantine walls and floor levels, as well as three of the folles found in the walking level substrate.

It was at this time that the graveyard was established at the site. A total of seventy-nine skeletons in fifty-eight burials have so far been excavated over the course of several campaigns. Originally, the individuals were interpreted as victims of an epidemic or of the earthquake that devastated Sagalassos in the seventh century ad on the basis of their presence among the debris caused by this seismic event (Waelkens et al., Reference Waelkens, Vermeersch, Paulissen, Owens, Arıkan, Martens, Waelkens and Poblome1997: 212, Reference Waelkens, Poblome, Paulissen, Talloen, Van Den Bergh, Vanderginst, Waelkens and Loots2000: 377). The study of the glass objects found in some of the burials (Lauwers, Reference Lauwers2008: 213–14), however, suggested a Middle Byzantine date for the graveyard, more specifically between the tenth and thirteenth centuries ad. This was later corroborated by radiocarbon dating on six of the skeletons (Ricaut & Waelkens, Reference Ricaut and Waelkens2008: 540). More recently, in 2016, three more skeletons were successfully radiocarbon-dated, providing dates between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries and, thus, confirming the proposed timeframe (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Plan of the graveyard around the converted temple of Apollo Klarios showing the presence of pectoral crosses.

None of the burials was located inside of the former church; they were arranged around it to the south and east, all the way down to the Lower Agora and the so-called Agora Gate on the south side of the square, the remains of both of which had largely been covered by (earthquake) debris. Northward and westward extensions of the graveyard are not attested so far as these areas have not yet been excavated, but they can be expected. The graveyard thus seemingly respected the Middle Byzantine phase of the church, although the latter has also not been completely fully excavated and burials may be present in the area of the narthex, as was the case in the lower city church of Amorium in the tenth–eleventh centuries (Ivison, Reference Ivison, Daim and Drauschke2010: 335–38). The study of the ceramics in the deposits in which the burials were arranged indicates that the walking level over the architectural debris, formed by the collapse of the western portico of the Lower Agora during the seventh century, was raised and levelled by the deposition of large amounts of earth during the subsequent centuries. In this way, a process of landscaping appears to have been carried out, partly in order to facilitate the layout of the graveyard (Cleymans & Poblome, Reference Cleymans and Poblomeforthcoming).

Generally, little variation in burial shape and content was observed. They were simple, shallow, roughly rectangular, or trapezoidal pits dug into the ground, which consists of an ophiolitic mix on the hill, and of debris and loose earth on the western slope of the Lower Agora and the Agora Gate (Figure 3). These pits were often lined with stone rubble, tile, or spolia, and sometimes covered with slabs or tiles. The deceased were placed into these pits, either individually or as multiple inhumations, some of the latter being secondary interments. The bodies of the deceased were oriented east-west, which was typical for Christian burial in Asia Minor as observed at other Dark Age and Middle Byzantine sites (Ivison, Reference Ivison1993: 7–8 and note 12). Their heads were at the west end of the grave so that upon rising they would be facing east, the direction from which Christ would appear at the time of his Second Coming (Matthew 24: 27). All the dead were interred in supine position, mostly with arms folded over the chest or abdomen. Only in two graves were the heads of the deceased propped up. They were probably placed directly in the pit and not laid to rest in wooden coffins as almost no nails were found. Nevertheless, the position of the foot bones of some well-preserved adult individuals indicated that they fell apart during decomposition. This is only possible if the remains were located in a cavity. The shape of some of the burial pits and the location of four nails in one grave suggest that the graves which were not covered with tiles or limestone slabs were possibly protected by a wooden cover. No grave markers have been found.

Figure 3. View of burial no. 2 of 2005, south of the church.

Of the group of seventy-four individuals studied, forty-six (62 per cent) were sub-adults, below eighteen years of age. In thirty-two cases (55 per cent of all graves), the graves contained only sub-adult individuals; seventeen (or 29 per cent) included only the remains of adults, and nine (or 16 per cent) those of sub-adults and adults together. The mixed distribution of adult and sub-adult graves around the church demonstrates that no special area was reserved for the burial of sub-adults (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Graph showing the number of individuals buried per grave.

Grave goods or funerary offerings placed in the graves during the burial ceremony, such as small ceramic pitchers and glass perfume flasks, which were common in late antique burials at Sagalassos (Talloen & Poblome, Reference Talloen and Poblome2014: 250–51), were no longer present. The absence of elements of clothing, like buttons, buckles, brooches or pins, suggests that the individuals were not buried wearing their normal garments but stripped of their clothing and dressed in funerary garments, which conforms to the standard burial practice of this period (Davies, Reference Davies1999: 199; Moore, Reference Moore2013: 112). On the other hand, personal ornaments, such as earrings, finger rings, glass bracelets, and necklaces with pendants, were found, which the deceased were either allowed to keep or given as grave goods. Only thirteen graves (22 per cent) contained such personal ornaments, a relatively low proportion, as also suggested by Sophie Moore's study of Byzantine burial practices in Asia Minor (Moore, Reference Moore2013: 140).

In several burials, these personal ornaments included cross-shaped pendants. Pendant crosses were a common feature in Byzantine burials; but, in spite of their popularity, studies devoted to them are few. Like hollow reliquary crosses, flat cross-shaped pendants are designated as enkolpia (Schoolman, Reference Schoolman, Daim and Drauschke2010: 375): while the former were objects of devotion containing a relic of a saint or a fragment of the True Cross, the latter were apotropaic amulets used to protect those who wore them. Reliquary crosses have recently been studied (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis2006), but the different types of pectoral crosses are rarely well-defined (for an exceptional study of crosses from Crimea, see Khairedinova, Reference Khairedinova, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012). They are even less well dated, with stylistic criteria generally serving as the basis (Schoolman, Reference Schoolman, Daim and Drauschke2010: 377). Together with other items found in burials, such as glass bracelets, copper-alloy earrings, and finger rings, the significance of these items of jewellery lie in the closed archaeological context in which they were found, as they were arranged ad personam. Consequently, they can inform us about the religious beliefs and the social practices of the deceased and the families that were burying them. Yet hardly any attention is ever paid to their archaeological context. Moreover, their interpretation is usually limited to being protective devices that accompanied their owners to the grave, while fundamental insight into the age and gender of the individuals that wore them is missing (e.g. Schoolman, Reference Schoolman, Daim and Drauschke2010). This is, to a large extent, the result of the state of research concerning Byzantine funerary practices. Although there are several studies on death and dying in the Byzantine period (e.g. Talbot, Reference Talbot, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009; Constas, Reference Constas and Krueger2010), much of this relies on literary sources. The latter generally concern the ruling elite, saints, or clergymen, who were concentrated in the imperial capital, thus creating uneven coverage regarding social class, gender, and geographical region. Only recently have archaeological studies started to shed more light on Middle Byzantine burial practices in Asia Minor (e.g. Moore, Reference Moore2013).

The aim of this article is to define the different types and chronology of cross pendants found at Sagalassos, as well as to characterize their use by looking at the age and gender of people who made use of them. In the case of Sagalassos, the 58 burials from the Apollo Klarios graveyard yielded a total of eleven pectoral crosses representing several types, which made it possible to establish a typology. Furthermore, elements of absolute radiocarbon dates calibrated with OxCal 4.3 (Bronk Ramsey, Reference Bronk Ramsey2009), and the atmospheric curve IntCal13 (Reimer et al., Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell and Bronk Ramsey2013) and relative (stratigraphic) chronology are available to ascertain a more accurate timeframe for the different types and uses of such pendants. Finally, studies conducted on the associated human remains allow us to establish the age and gender of their owners.

Typology

The eleven pectoral crosses found in the burials of the Apollo Klarios graveyard represent five main types. Some could be divided into subtypes.

Type 1

Type 1 consists of forged iron cross-shaped pendants.

Type 1a

This subtype comprises forged iron cross-shaped pendants made by bending an iron rod with a rectangular section. This resulted in the two short and two long arms of the cross, on whose upper part a suspension loop was added.

SA-1999-LA-18.3 ( Figure 5(k))

This forged iron cross-shaped pendant (19 mm wide; the top part is badly corroded) was found inside burial no. 2, excavated in 1999 (SA-1999-LA-II: sector 2390/2315; layer 2), which was located between the eastern temenos wall of the former sanctuary and the western terrace wall of the Lower Agora. Within this grave, two children aged one and a half (± one year) and three (± one year) were buried in an east-west orientation with their heads at the western end of the grave, facing east. The skeletons of both children were disturbed and incomplete. This made it impossible to reconstruct the position of the bodies and to associate the cross with either individual. The stone alignment of the burial pit, measuring 0.45 × 0.35 m, was only partly preserved due to a later disturbance of the grave. This cross pendant was found together with two copper-alloy crosses of Types 2a and 5 (see below). The Type 1a and Type 5 crosses were joined because of corrosion, suggesting that they were placed closely together in the burial, probably originally as part of the same necklace. No other items of adornment were found.

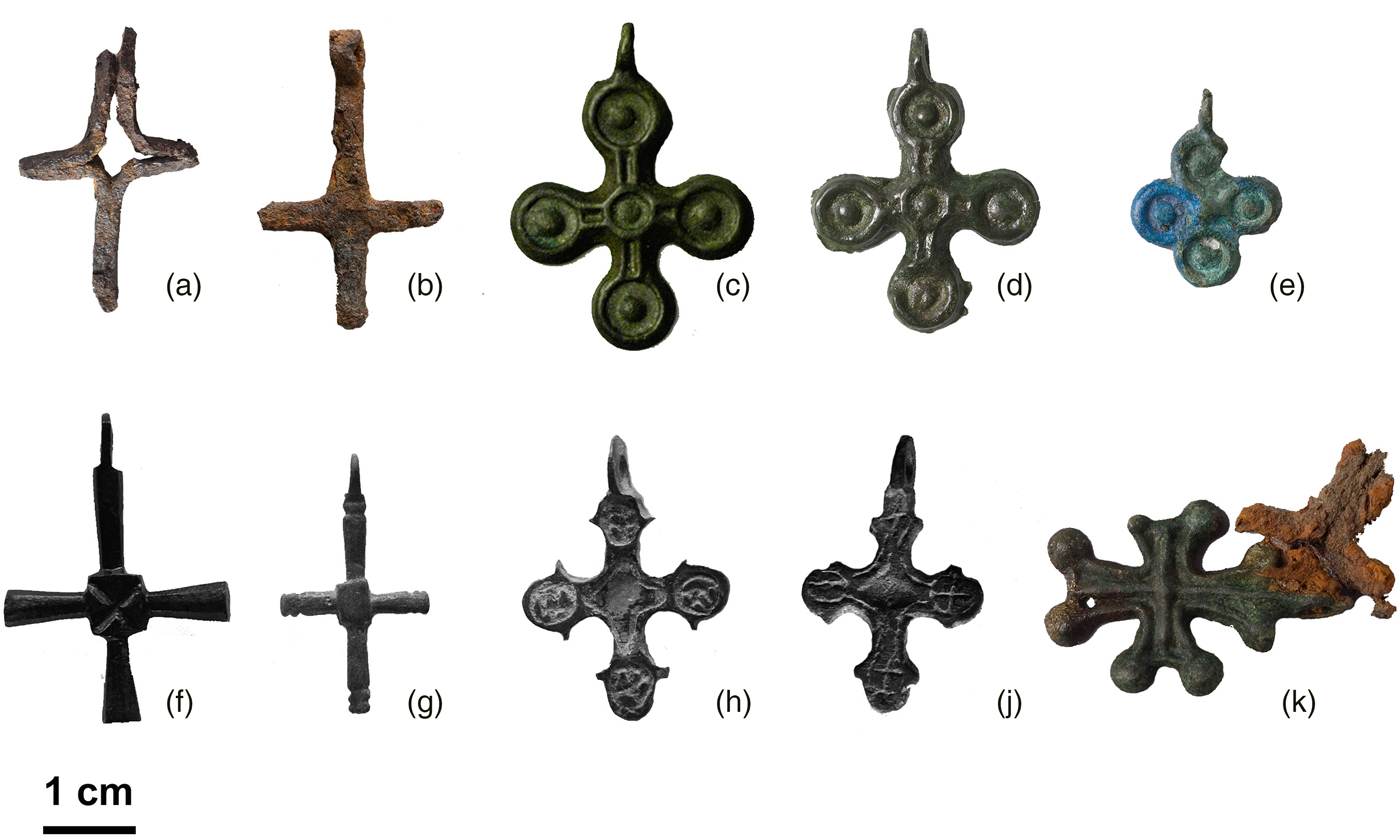

Figure 5. Overview of the eleven pectoral crosses found in Middle Byzantine burial contexts.

SA-2008-AK2-58-66 (Figure 5(a))

This forged iron cross-shaped pendant (30 mm long and 19 mm wide; its suspension loop is no longer present) was found south of the Apollo Klarios chapel, within the former temenos, in burial no. 4 of 2008 (SA-2008-AK2-IV: sector 2290/2365, locus 58). In this grave, the remains of an adolescent (fourteen to eighteen years old) and a child (three to five years old) were found. The adolescent was oriented east-west, facing east, in a supine position with the legs stretched out and the arms folded over the chest, while the child's bones were mingled with those of the adolescent. The grave (2.00 m long and 0.46 m wide) was cut out of the ophiolite bedrock and lined with tiles. A tile cover, 0.20 m above the grave floor, separated this burial from a burial superimposed on it (burial no. 3 of 2008).

A similar iron pectoral cross was found in a burial at the Middle Byzantine graveyard in the village of Boğazköy in Galatia, which was allegedly abandoned in the second half of the eleventh century due to the Seljuk invasion of the region (Böhlendorf-Arslan, Reference Böhlendorf-Arslan, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 365 fig. 13.19), while at Zeytinli Bahçe (Osrhoene) a comparable pendant was found in a grave dated to the twelfth–thirteenth centuries (Dell'Era, Reference Dell'Era, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 404 fig. 12g and 405).

Type 1b

This subtype takes the shape of a forged iron cross-shaped pendant made by joining two flat and thin rods. A suspension loop for hanging by a string or chain, made by folding back the top of the iron rod, is present on the upper arm of the cross, which is longer than the others.

SA-2005-AK-14-42 (Figure 5(b))

This forged iron cross-shaped pendant (32 mm long and 20 mm wide) was found in burial no. 2 of 2005 (SA-2005-AK-II: locus 16 of sector 2290/2365) to the south of the church. This pit burial contained the skeleton of an infant between one and two years of age (SA-2005-AK-38). The body was interred in supine position with the legs stretched and the arms folded on the chest. This child was oriented east-west with the head at the west end of the grave. The pit (0.77 m long, 0.26 m wide, and 0.18 m deep) had a lining of limestone rubble. In addition to the iron cross-shaped pendant around its neck, the child wore a cobalt blue glass bracelet around its right wrist (SA-2005-AK-40) and a copper-alloy ring on one of its left fingers (SA-2005-AK-42); furthermore, a copper-alloy earring in the form of a simple hoop with a hook and loop fastening (SA-2005-AK-42) was found. The presence of a glass bracelet may identify the infant as a girl, as such bracelets were generally worn by female individuals (Lauwers et al., Reference Lauwers, Degryse, Waelkens, Drauschke and Keller2010: 150). The ceramic material of the grave fill provided a terminus post quem in the Middle Byzantine period (eleventh–thirteenth century ad). This is confirmed by the glass bracelet, which can be dated between the tenth and thirteenth century ad (Lauwers et al., Reference Lauwers, Degryse, Waelkens, Drauschke and Keller2010), and a radiocarbon date between 1170 and 1285 cal ad (at 2σ or 95.4 per cent probability).

Two similar forged iron cross pendants were found at Zeytinli Bahçe in a secondary burial (no. 28) dated to the twelfth–thirteenth century (Dell'Era, Reference Dell'Era, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 404 fig. 12e–f and 405).

Type 2

Type 2 comprises copper-alloy crosses cast in moulds, with arms ending in roundels in the shape of dotted circles.

Type 2a

This subtype consists of four arms, two shorter horizontal and two longer vertical ones. The edges of the arms are indicated by fluting. The arms end in roundels in the shape of dotted circles which imitate inlaid decoration. Such a roundel is also present at the centre of the cross. A suspension loop for hanging on a string or chain is present on the top of the upper roundel.

SA-1999-LA-18.2 (Figure 5(c))

This copper-alloy cross-shaped pendant (33 mm long and 25 mm wide) was found on the Lower Agora, in burial no. 2 excavated in 1999 (SA-1999-LA-II). This grave has already been described (see Type 1a). As mentioned, it was found together with an iron pectoral cross of Type 1a (SA-1999-LA-18.3) and a copper-alloy cross of Type 5 (SA-1999-LA-18.1).

SA-1996-LA-46 (Figure 5(d))

This copper-alloy cross-shaped pendant (33 mm long and 25 mm wide) was found on the Lower Agora (sector 2320/2365, layer 2) in burial no. 2, the grave of a child (aged one and a half to two years) excavated in 1996 (grave SA-1996-LA-II). This child was buried in a supine position with legs stretched out. The individual was oriented east-west, with the head at the west end of the grave, facing east. The grave was lined with irregular limestone blocks. Besides the cross described here, another pendant of Type 4a (SA-1996-LA-47) was found. Both were found on top of the upper left ribs and the left clavicle, causing a green discoloration of the bone. A small copper-alloy ring (6 mm in diameter), found underneath the skull, probably served as an element of the string on which the cross used to hang. The radiocarbon date of the skeleton could be calibrated to 1025–1168 cal ad (at 2σ or 95.4 per cent probability).

Similar crosses have been found in cemeteries in Thessaloniki, which were dated to the mid-thirteenth to mid-fifteenth century ad (Antonaras, Reference Antonaras, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 123 and fig. 10), and three identical crosses were found in the burial of a child (no. 133) at Herakleia Perinthos, dated to the ninth–twelfth century ad (Westphalen, Reference Westphalen, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 132 fig. 5, 133 fig. 6 and 134).

Type 2b

This subtype represents a copper-alloy clover-shaped pendant cast in a mould, consisting of four roundels in the shape of dotted circles forming a cross around a central circular pellet. A suspension loop is present on top of the upper disk.

SA-1995-AG-301 (Figure 5(e))

This cross (21 mm long and 16 mm wide) was found in burial no. 3 at Agora Gate (SA-1995-AG-III: sector 2325/2345, layer 4), excavated in 1995. The grave yielded the remains of a child (c. two years old) and a woman (aged twenty-one to twenty-three years). The remains of the woman were disturbed, but still articulated. The individual was interred in a supine position, with the legs stretched and the arms positioned next to the body. She was oriented east-west, with head towards the west. The skeleton of the child was less well preserved: the remains were reduced and very disturbed. This makes it impossible to associate the cross directly with either of the skeletons. The grave pit, measuring 1.80 × 0.65 m, was covered and lined with stone rubble. The pottery found within the fill of the burial provided a Middle Byzantine terminus post quem for this grave. The adult individual was radiocarbon-dated between 1185 and 1290 cal ad (at 2σ or 95.4 per cent probability).

Type 3

Type 3 comprises copper-alloy cross-shaped pendants cast in moulds, consisting of four flaring arms, two shorter horizontal and two longer vertical ones. The arms of the cross terminate in roundels with two small teardrops on either side of them. A suspension loop is present on top of the upper arm.

SA-1995-AG-250 (Figure 5(h))

Within each of the roundels of this cross-shaped pendant (31 mm long and 23 mm wide) remains of yellow enamel were present. The intersection of the arms was hollowed, probably indicating the presence of a glass (or enamel) inlay which is now missing. The back of the cross is flat and without ornamentation. It was found in burial no. 2, located on top of the Agora Gate staircase and excavated in 1995 (SA-1995-AG-II: sector 2325/2345, layer 4). Within this grave, measuring 0.40 × 0.80 m, the remains of a two to three year old child were unearthed. This child was oriented east-west, its head towards the west, in a supine position with the legs stretched and the arms folded on the abdomen. The grave itself was a simple pit. The cross was found on the chest of the child.

SA-1995-AG-323 (Figure 5(j))

The lower arm of this copper-alloy pendant (30 mm long and 20 mm wide) is longer than the others. A small cross is incised in each of the roundels at the end of the arms. The intersection of the arms is hollowed out, probably for the inset of glass paste, now lost. The back of the cross is flat and without ornamentation. The cross was found in burial no. 7, excavated in 1995 on top of the Agora Gate staircase (SA-1995-AG-VII: sector 5330/4765, layer 4). Within this burial, the remains of a child (aged one to two years) were unearthed. The reduced remains were scattered over the grave, but it was still possible to ascertain that the grave was oriented east-west with the head at the west end. The cross was found on the body of the deceased. The burial pit, measuring 0.80 × 0.60 m, was lined with rubble stones, while its floor was paved with tiles and bricks. The most recent pottery from its fill could be dated between the seventh and tenth centuries ad, giving us a terminus post quem for this grave.

Crosses with convex semi-circular terminals and small protrusions were common from the eleventh century onwards (Evans & Wixom, Reference Evans and Wixom1997: cat. no. 124). A similar cross was found in the burial of a child (no. 133) at Herakleia Perinthos, dated to the ninth–twelfth centuries ad (Westphalen, Reference Westphalen, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 132 fig. 5, 133 fig. 6, and 134). Another example of this type was excavated at Saraçhane (Istanbul), in an undated context (Harrison, Reference Harrison1986: 269 no. 625, plate 426).

Type 4

Type 4 refers to copper-alloy cross-shaped pendants cast in moulds, consisting of a cubic centre with four cone-shaped arms. A suspension loop is present on top of the upper arm.

Type 4a

This subtype consists of a cubic centre with four identical cone-shaped arms. On the top surface of the cube, a cross is incised diagonally.

SA-1996-LA-47 (Figure 5(f))

This copper-alloy cross-shaped pendant (34 mm long and 25 mm wide) was found in burial no. 2, which was excavated on the Lower Agora in 1996 (grave SA-1996-LA-II: sector 2320/2365, layer 2). The grave has already been described in the discussion of a cross of Type 2a (SA-1996-LA-46).

A comparable cross was found in the burial of a child (no. 133) at Herakleia Perinthos, dated to the ninth–twelfth century ad (Westphalen, Reference Westphalen, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 132 fig. 5, 133 fig. 6, and 134).

Type 4b

Subtype 4b consists of a cubic centre with four cone-shaped arms, two shorter horizontal and two longer vertical ones. Each of the arms ends in two drum-shaped ornaments.

SA-1995-AG-296 (Figure 5(g))

The copper-alloy cross (28 mm long and 16 mm wide) was found in burial no. 10 excavated in 1995 on top of the Agora Gate staircase (SA-1995-AG-X: sector 2325/2350, layer 4). This grave of a child (aged one to one and a half years), measuring 1.08 × 0.73 m, was partly stone-lined on the south side, and some stones also covered it. The skeletal remains were very disturbed, with the whole left arm missing. An east-west orientation with the head at the west end was still observable. The cross was found on the child's chest.

Pectoral crosses similar to this subtype were found at Yumuktepe in Cilicia (Köroğlu, Reference Köroğlu, Caneva and Sevin2004: no. 5) and at Zeytinli Bahçe in Osrhoene (Dell'Era, Reference Dell'Era, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 404 fig. 12h and 405) in contexts dated to the eleventh–thirteenth and twelfth–thirteenth centuries, respectively.

Type 5

This type of copper-alloy cross-shaped pendant cast in moulds consists of four arms, two shorter horizontal and two longer vertical ones. Each of the arms has two spherical knobs on its splayed ends and a rib in the middle of the arm. The edges of the arms are indicated by fluting. A suspension loop is present on top of the upper arm.

SA-1999-LA-18.1 (Figure 5(k))

The copper-alloy cross-shaped pendant (32 mm long and 20 mm wide) was recovered in burial no. 2 on the Lower Agora in 1999 (2390/2315, layer 2). This grave has already been discussed since it also contained an iron cross of Type 1 (SA-1999-LA-18.3) and a copper-alloy cross of Type 2a (SA-1999-LA-18.2). The Type 5 and Type 1a crosses were joined by corrosion, suggesting that they were placed closely together during burial, probably originally as part of the same necklace.

A similar pectoral cross was found in a burial at the Middle Byzantine graveyard in the village of Boğazköy which was allegedly abandoned in the second half of the eleventh century due to the Seljuk invasion (Böhlendorf-Arslan, Reference Böhlendorf-Arslan, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 365 fig. 13.20). A comparable cross was also present in the burial of a child (no. 133) at Herakleia Perinthos, dated to the ninth–twelfth centuries ad (Westphalen, Reference Westphalen, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 132 fig. 5, 133 fig. 6, and 134).

Chronology of the Crosses

The pectoral crosses from Sagalassos can all be firmly placed in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries on the basis of the radiocarbon dates available for some of the burials and the typological parallels with examples from other excavated sites, from Thrace in the west to Osrhoene in the east. These parallels indicate that the typology was common to a large network of workshops scattered throughout the Byzantine Empire.

As Table 1 shows, the three graves with crosses for which radiocarbon dates are available all fall within the eleventh–thirteenth centuries.

Table 1. Radiocarbon dates of the skeletal remains associated with crosses.

Within both graves SA-1996-LA-II and grave SA-1995-AG-III, a cross of Type 2 was found. Yet, the radiocarbon dates of the associated human remains do not overlap. It, therefore, seems that the clover-shaped subtype 2b from grave SA-1995-AG-III is more recent than subtype 2a from SA-1996-LA-II. While Type 2a can be attributed to the eleventh–twelfth centuries, Type 2b belongs to the late twelfth–thirteenth century. The former date contradicts a proposed late Byzantine date (thirteenth–fifteenth century ad) for Type 2a at Thessaloniki (Antonaras, Reference Antonaras, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012), but corresponds to the (broad) date at Herakleia Perinthos. Given that Type 2a was found together with Type 4a in SA-1996-LA-II, and with Type 1a and Type 5 in SA-1999-LA-II, a similar date for those types is implied.

Since Type 1a is contemporary with Type 2a and can be dated to the eleventh–twelfth centuries ad, while Type 1b, found in SA-2005-AK-II, was dated between the late twelfth and the end of the thirteenth century ad, it is safe to assume that these types also succeeded each other.

The radiocarbon dates also indicate an eleventh–twelfth century origin for Type 4a. For Type 4b no such date is available, nor were there any other objects present in burial SA-1995-AG-X which could provide chronological indications. Yet, parallels from Yumuktepe and Zeytinli Bahçe (see above) suggest a twelfth–thirteenth century date for this type of pectoral cross, which identifies it as a later development.

Finally, the association of the dated Type 2a with Type 5 in SA-1999-LA-II also places the latter in the eleventh–twelfth centuries. Crosses of Type 1a and Type 5 were also found at Boğazköy in the graveyard of a Byzantine settlement laid out around a monastery (Böhlendorf-Arslan, Reference Böhlendorf-Arslan, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012). The destruction of the settlement during the late eleventh century, associated with the Seljuk invasions of Anatolia, provides a plausible terminus ante quem for the use of the cemetery, and confirms the suggested date of the types mentioned.

Like Type 4b, Type 3, of which the two specimens were found in contexts not dated by 14C and without any other grave goods, could not be dated on the basis of internal criteria. However, the contemporaneity of this type with some of the other pectoral crosses attested at Sagalassos can be deduced from examples from the Middle Byzantine graveyard at Herakleia Perinthos. There, a necropolis was established on top of an abandoned fifth-century basilica between the ninth and twelfth centuries, and remained in use until the thirteenth–fourteenth century (Westphalen, Reference Westphalen, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012). One of the burials (no. 133), a simple pit burial of a child broadly dated to between the ninth and twelfth centuries, contained six crosses in total. They were all part of the same chain found around the neck of the individual and were of four different types, all of which are also present at Sagalassos, namely three crosses of Type 2a, together with crosses of Types 4a, 5, and 3 (Westphalen, Reference Westphalen, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 132 fig. 5, 133 fig. 6, and 134). We may therefore conclude that Type 3 can also be placed in the eleventh–twelfth century.

It, thus, seems that Types 1a, 2a, 3, 4a, and 5 were all contemporary and can be dated to the eleventh and twelfth centuries, while Types 1b, 2b, and 4b date to the late twelfth to thirteenth centuries. Nonetheless, no strict chronological sequence should be envisaged. The continued use of Type 1a and the origin of Type 1b in the twelfth century is suggested by examples from eastern Anatolia at Zeytinli Bahçe (Osrhoene) in a grave (no. 28) dated to the twelfth–thirteenth century (Dell'Era, Reference Dell'Era, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012); although the nature of the burial, an ossuarium, could mean that the contents of older graves were mixed with new inhumations. The possible overlap of subsequent types indicates that the transition from the one type to the other was not an abrupt process, but rather a slower evolution.

A horizontal stratigraphy can be suggested for the layout of the graveyard on the basis of the nine radiocarbon dates obtained so far. The calibrated dates from the skeletons excavated in the debris on the west side of the Lower Agora and those between the temenos wall and the western terrace wall of the agora seem to be older than the dates obtained for those buried above the Agora Gate staircase. This development is largely corroborated by the proposed date of the pectoral crosses (Figure 2). It, thus, seems that people were originally buried closer to the sanctuary and then gradually areas further removed from it were brought into use. The aspiration of being interred as close as possible to the church was common practice in Byzantine Asia Minor (Ivison, Reference Ivison1993: 66–76). As the burial densities within and outside the temenos wall of the former Apollo Klarios temple are very different, this demarcation was obviously still important in Middle Byzantine times. Within the enclosure, the density was much greater.

Use of the Crosses

In the discussion of the different types, it becomes clear that the eleven pectoral crosses found at Sagalassos were present in burials of sub-adults, a characteristic which they shared with other types of personal adornment. In Byzantine times, the bodies of children were laid out in much the same way as those of adults, but, unlike adults, they were often adorned with jewellery (Talbot, Reference Talbot, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 300–01). While, in the Early Byzantine period, jewellery was found in both children's and adults' graves, in Middle Byzantine times it was no longer given to adult individuals (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 193), and the data from Sagalassos confirm this. Only thirteen of the fifty-eight burials (or 22 per cent) contained objects; and, in all of them, remains of children were found, either in a single or a multiple burial (with an adult or another child).

The shape and size of most items, such as the glass bracelets all having a diameter of 50 mm or less (Lauwers, Reference Lauwers2008), allows them to be identified as miniature pieces, designed for children. Further, finger rings found in graves at Boğazköy were worn by children, as indicated by their small diameter; although glass bracelets there were worn by both children and adults (Böhlendorf-Arslan, Reference Böhlendorf-Arslan, Böhlendorf-Arslan and Ricci2012: 363–64). The practice of adorning children of both genders with items of jewellery is attested throughout the history of the Byzantine Empire, and parents also took care to ornament their children in death (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 187–91). At Sagalassos, this is illustrated in particular by burial SA-2005-AK-II where, together with the pectoral cross of Type 1b, a copper-alloy ring, a glass bracelet, and a copper-alloy earring have been found (see above; Figure 3). Another example at Sagalassos is grave 6, which was excavated west of the western terrace wall of the Lower Agora in 1998. In this grave, a two-year-old child (± eight months) had six glass bracelets on its right arm and one on its left. As the ornaments given to the child were too cumbersome to have been worn on a daily basis, it seems that these glass bracelets did not serve as jewellery during life, but were given to the child as grave goods. Similar practices have been observed at the Djadovo necropolis in Bulgaria, where a five to six-year-old was buried with eleven glass and copper-alloy bracelets on its right arm (Fol et al., Reference Fol, Katinčarov, Best, de Vries, Shoju and Suzuki1989: 338).

The pendant crosses are the most common ornaments recovered so far, since they account for thirty-seven per cent of all the objects. The prevalence of jewellery in children's burials from the Middle Byzantine period illustrates the perceptions and beliefs about premature death in ancient societies. Crosses were part of the adornment of children, but they were also associated with a desire to protect them. This was perpetuated in funerary rituals in which we see the desire to protect a child on its journey to the realm of the dead (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 194).

Yet, not all children had a cross pendant. At Sagalassos, they appear to have been typical gifts for small children, since all the crosses that were found accompanied children between one and five years old. Despite their very young age, the fact that the children were given a formal burial amidst the adult members of the community suggests that they had been baptized and were considered part of the local congregation. Only three children younger than one year old have so far been found, suggesting that unbaptized neonates were buried separately, as was the case in Amorium (Ivison, Reference Ivison, Daim and Drauschke2010: 338). The prominence of devices like pectoral crosses intended for protecting children is important for understanding the role of children in local society during the Byzantine period. Keeping children healthy was a universal preoccupation that the Sagalassians were deeply concerned with.

Of the seventy-four skeletons studied at Sagalassos, at least forty-six (or 62 per cent) belonged to sub-adults. Of those forty-six, thirty-five were (well) under five years old, not including the unbaptized neonates, illustrating the traditionally high rate of infant mortality in pre-industrial times. In Byzantine society, the death of infants and children was an all-too-common phenomenon. Recent excavations of Byzantine cemeteries are generating significant new data on sub-adult burial that indicate high death rates (40 to 50 per cent) among infants and children (Talbot, Reference Talbot, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009). Children's skeletons represent a substantial percentage of the individuals whose remains have been excavated, even if they are less likely to be preserved and are more difficult to recover.

Earlier studies indicate that the contemporary community at Sagalassos was in poor health (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, De Cupere, Marinova, Van Neer, Waelkens and Richards2012), which will have contributed to this high death rate among children. Scurvy, iron-deficiency anaemia (indicated by cribra orbitalia) as well as malnutrition (reflected by linear enamel hypoplasia), which would have made children more vulnerable to infectious disease, have been suggested as general causes of high infant and child mortality during this period (Talbot, Reference Talbot, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 287). At Sagalassos, the evidence also points in this direction: cribra orbitalia has been observed on nine skeletons and two individuals showed linear enamel hypoplasia.Footnote 1

Moreover, a further particular cause of death can be suggested, based on the evidence from Sagalassos. Recent isotopic analysis for the detection of breastfeeding and weaning patterns in Greek Byzantine populations has demonstrated that weaning occurred around the ages of two to three (Bourbou, Reference Bourbou2004: 67–68; Bourbou & Garvie-Lok, Reference Bourbou, Garvie-Lok, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009). This age group sees a high incidence of mortality at Sagalassos, where we have twenty-nine 2-3 year-old individuals (39 per cent). The death of a major portion of the infants and young children buried in a Middle Byzantine cemetery at Xironomi in Greece has also been related to weaning (Tritsaroli & Valentin, Reference Tritsaroli, Valentin, Jener, Muriel and Olària2008: 105). During weaning, breast milk was substituted with preparations, including wheat or barley cooked in water as well as goat's milk, sometimes mixed with honey (Jackson, Reference Jackson1989). The infant deaths reveal the dangers of malnutrition and diarrhoea resulting from the shift to a diet of cereal and goat's milk. Weaning was a crucial time in a child's life, and the nutritional value of supplementary foods, as well as sanitary conditions in which feeding took place, were of vital importance. A clear indication of this is that the majority of individuals with cribra orbitalia fall within this age range (six out of nine, or 67 per cent). Therefore, we consider it as no coincidence that pectoral crosses were found especially in this age group, with all individuals with crosses belonging to this subset.

In popular belief, the high incidence of infant mortality was attributed to the evil eye (Dickie, Reference Dickie and Maguire1995). Pregnant women and young children were thought to be particularly vulnerable to its influence. One of its manifestations was to provoke the action of a female demon, commonly identified as Gello, whose aggression was principally directed against babies and mothers immediately before or after delivery (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 197). Amulets were often used to protect newly-born children against the demon during the dangerous period between birth and baptism (Talbot, Reference Talbot, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 291). Gello was believed to pose a danger especially in the first weeks after birth, but the evil eye was a constant threat for small children, who needed the protection of a multiplicity of practices and devices (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 200). The fight against such demonic activity at Sagalassos is already reflected by a group of sixth-century pendant amulets (Talloen, Reference Talloen, Lavan and Mulryan2011: 597–99). One side of these amulets bears the image of the Holy Rider, identified as Solomon, attacking the prostrate female demon. On the other side, a clover-shaped cross composed of four roundels is depicted.

Since the Early Byzantine period, the cross was promoted by the Church Fathers as the most powerful agent against evil (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 202). Consequently, the use of pectoral crosses became commonplace, gradually superseding the use of other types of protective devices. They afforded their wearers protection from evil spirits that constantly threatened all aspects of daily life (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 202, Reference Pitarakis and Krueger2010: 164). The Middle Byzantine cross pendants may, thus, have been used as apotropaic instruments to protect infants from premature death during or after the period of weaning. This would make them a material manifestation of the struggle of parents to keep their infants alive during this most dangerous transition in life. The concern for salvation meant that the crosses also accompanied their recipients to their graves (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis and Krueger2010: 173).

Yet, only nine of the twenty-nine two/three-year-olds (or 31 per cent) received a cross. Another criterion, perhaps gender, may, therefore, have been influential. At other Middle Byzantine sites, the bulk of the jewellery was found in the burials of little girls (e.g. Laskaris, Reference Laskaris2000: 248; Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 202). This perhaps reflected the custom of ‘marriage to death’, the perception of death as a marriage to the underworld deities, especially in the case of a young unmarried person (Pitarakis, Reference Pitarakis, Papaconstantinou and Talbot2009: 194). It is, however, extremely difficult to determine the sex of the skeletal remains of a sub-adult (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Dupras and Tocheri2005: 10). The analysis of the aDNA of some skeletons from the Sagalassos graveyard indicated a female sex for one of the children between two and three years old (Jehaes et al., Reference Jehaes, Waelkens, Muyldermans, Cassiman, Smits, Poblome, Waelkens and Loots2000: 829). This girl, however, was not given any grave goods, be it jewellery or cross. It, therefore, is not possible to say anything of the gender-association of the crosses at the present time.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper is to present the different types of pendant crosses found in the burials of a Middle Byzantine graveyard at the Pisidian settlement of Sagalassos, and the light they shed on funerary practices in this part of the Byzantine world. In general, the crosses could be dated to between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries ad, providing an indication for the lifespan of the cemetery. Moreover, the typological evolution, which was corroborated by parallels from other sites in the Byzantine Empire, suggesting a supra-local applicability, makes it possible to construct a horizontal stratigraphy for the graveyard. The pectoral crosses discussed here proved to belong in most cases to very young children between two and three years old, a period during which they were weaned. These crosses constitute a category of material culture that not only provides insights into the lives of the Byzantine population, especially during the period of early childhood, but are also the material manifestation of the intersection of popular religion, magic, and funerary rites. They reflect Byzantine parents’ profound concerns with the health and well-being of their offspring, and illustrate how they resorted to such apotropaic instruments to protect their infants, in life and death.

Acknowledgements

The authors are members of the Sagalassos Archaeological Research Project. From 1990 to 2013, the fieldwork activities and research programme were directed by Marc Waelkens and from 2014 onwards by Jeroen Poblome (both University of Leuven, Belgium). This research was supported by the Belgian Programme on Interuniversity Poles of Attraction, the Research Fund of the University of Leuven, and the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO). We would like to thank the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey, its General Directorate of Culture and Museums (Kültür Varlıkları ve Müzeler Genel Müdürlüğü), and its representatives for permission to excavate, for support, and much-appreciated help during the fieldwork campaigns.