Legislative responses to social changes signify how representative democracy works. As delegates or trustees, lawmakers are expected to grasp growing problems in a changing society and propose shared solutions in the legislature chamber. If the legislative branch continually fails to address political, social and economic deficiencies, the deliberative body of government would develop crises of legitimacy and stability. Consequently, a substantial body of literature has developed to examine how lawmakers act in response to demands from the public (Canes-Wrone et al. Reference Canes-Wrone, Brady and Cogan2002; Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963). Yet, the link between constituents’ interests and their representatives’ behaviour appears to be neither simple nor straightforward. Moe (Reference Moe1990: 233) points to the ‘tables being turned’, with lawmakers now setting the redistricting rules on how the represented select their representatives. Numerous studies also suggest that money and the media, not voters, are the main driving forces and voting determinants for lawmakers. Bernstein (Reference Bernstein1989: xiii) even claims that ‘the notion of constituents controlling the behaviour of their representatives is a myth’.

Moreover, the notion of legislative responses to constituents’ interests requires further scrutiny in newly democratized countries. Unlike the old and original representative regimes, new and emerging democracies do not necessarily find their legislative body to be a bottom-up institution. In the initial stage of nation-building, the constitution in new democracies creates the legislature as a critical part of the democratic system. The constituency, however, tends to arrive later on as the society changes and develops over time. In the meantime, lawmakers and parties only care about their grasp on political power, not constituency preferences. Thus, the question is whether representatives shift their focus to the role of representation as the political system becomes democratic and the society becomes diversified.

In this context of the connection between the represented and the representatives being seriously re-examined, we explore whether and how lawmakers respond to the rise of economic inequality in a new democracy like South Korea. In the course of fast-growing economic development, the East Asian economy has experienced an increasing level of income disparity between the top earners and middle-income families. The degree of pre-tax income inequality is one of the highest among the OECD countries, and the effects of income redistribution through taxes are relatively small compared with other industrialized countries. Temporary employees make up almost one-third of the whole labour market, and record-breaking corporate earnings have not necessarily translated into wage increases. While only 22 of the 100 richest people in the US have inherited their wealth, 84 of the 100 wealthiest people in Korea were born with a silver spoon (Jang 2014).

Do lawmakers in the East Asian new democracy address this growing problem of income inequality? If so, how? If not, why not? We study the 18th National Assembly (2008–12) in Korea to examine legislative activities surrounding the subject of economic redistributive policies. The redistributive measures include corporate tax laws, comprehensive real estate tax laws, minimum wage laws and welfare transfer laws. As in many other legislative branches in the world, it is not easy to enact laws in the Korean National Assembly. And yet, at the same time, representatives are supposed to respond to their constituency’s calls for policy changes. According to the definition of representation, the ‘single-minded-seekers-of-reelection’ (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974) should legislate what their constituents prefer (Canes-Wrone et al. Reference Canes-Wrone, Brady and Cogan2002; Clausen Reference Clausen1973; Key Reference Key1961; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1989; Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963). In a nutshell, whether and how lawmakers respond to constituents’ demands provides the key to the functioning of representative democracy.

To understand the legislative response in new democracies to constituents’ concerns over economic inequality, we turn to co-sponsorship behaviour in the National Assembly in Korea. Through coding and indexing lawmakers’ co-sponsorship strategies on the subject of economic inequality and income redistribution, we build our dependent variables and test a series of hypotheses to find out whether Korean representatives react to growing socioeconomic problems. Do Korean lawmakers respond to constituents’ ideological and policy preferences? Does the number of voters in poverty in their respective districts affect lawmakers’ legislative interests? What explains legislators’ behaviour in Korea? In this article, we examine the relationship between lawmakers and constituents in Korea where party discipline and party voting has long dominated legislative politics.

DEMOCRATIC RESPONSES TO ECONOMIC INEQUALITY

Political science is a relatively late arrival when it comes to addressing income inequality as a political problem. Exploring the causes and consequences of unequal democracy in the US, Bartels (Reference Bartels2008) posits that partisan politics and an inattentive public are responsible for income distribution being skewed towards the wealthy. While historical records speak volumes about party differences over the issue of inequality, voters have often sided with the Republican Party, which has actually exacerbated economic inequality. Bartels clarifies the differences of preferences and performances between Republican presidents and Democratic ones over inequality. Hacker and Pierson (Reference Hacker and Pierson2010, Reference Hacker and Pierson2012) look deeper into partisan politics and organized interests and find that the Democratic Party is now no different. As money plays an ever-increasing role in the so-called ‘candidate centred’ politics during the era of television campaign commercials, Hacker and Pierson notice that the Democratic Party shifted its policy and coalition focus from labour unions and low-income households to Wall Street and Silicon Valley.

Schlozman and her colleagues for the APSA Report on Inequality (2004) also confirm that parties are more interested in the median contributor, who is more affluent than the median voter. As a result, Democratic and Republican activists have become concerned that their pursuit of ideal policy matters such as inequality might backfire against their own party and the wealthy median voter. When it comes to the bigger picture of inequality, McCarty et al. (Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2006) suggest that increases in political polarization coincide with patterns of income inequality in America. In other words, the trend of income inequality and partisan polarization shows astonishingly similar trajectories over time. During periods of serious income inequality, political parties become ideologically polarized, whereas the intensity of polarization dulls in times of relative income equality.

The existing literature, while having no shortage of discourse on behavioural and partisan dimensions of inequality issues, offers relatively little about how representatives actually address the problem of an unequal society. Indeed, as democratic responsiveness refers to the translation of public preference into public policy, students of the legislative branch have long tried to understand the connection between preference and policy. Starting with the seminal analyses of constituency influence by Miller and Stokes (Reference Miller and Stokes1963), a substantial body of research has emerged to address a multiplicity of the constituency elements. Key (Reference Key1961) emphasizes the importance of public input through the notion of ‘latent opinion’, whereas Clausen (Reference Clausen1973) and Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1989) analyse congressional voting from the angle of issues and agendas. Confronting the Michigan School’s ignoring of the link with policy and focus on ‘partisan identification’, Jacobson (Reference Jacobson1987) explains why incumbent lawmakers are ‘running scared’, and Canes-Wrone et al. (Reference Canes-Wrone, Brady and Cogan2002) track down the evidence of representatives who are ‘out-of-touch, out-of-office’.

What about the legislative response in new democracies? In the context of consolidating a democratic system in Korea, the link between lawmakers and constituents is not as solid as in the case of advanced democratic countries. Over the past few decades, individual representatives in Korea have been highly loyal to the party leadership and presidents, not to the district constituency. In Korea, there are still a huge number of non-competitive districts where parties’ regional ties dominate the election outcomes. As a consequence, party leaders’ heavy-handed influence on lawmakers, particularly through the candidate selection processes, has ultimately made it difficult for representatives to be independent and connected to their constituents. Essentially, party discipline has been so strong in Korea that lawmakers have simply worked as partisan foot soldiers (Han Reference Han2011, Reference Han2013; Jeon Reference Jeon2006; Lee Reference Lee2005b; Lee and Lee Reference Lee and Lee2011; Seo and Park Reference Seo and Park2009). Yet, as the political system has become more democratic and as socioeconomic interests tend to be diversified, lawmakers in a new democracy such as Korea face an old challenge in the representative system: legislative responses to constituents’ interests.

Since the introduction of the recorded voting system by the 16th National Assembly (2000–4), a growing number of empirical studies have investigated legislators’ responsiveness to the public at the district level (Lee and Lee Reference Lee and Lee2011). Some studies focus on the introduction of bills and resolutions in the National Assembly to investigate who proposes more bills and why (Choi Reference Choi2006; Jeong and Chang Reference Jeong and Chang2013; Kim Reference Kim2006; Lee Reference Lee2009; Sohn Reference Sohn2004). Also, an increasing amount of research examines lawmakers’ roll-call voting to find out what explains their legislative choices (Jeon Reference Jeon2006, Reference Jeon2010; Lee Reference Lee2005a, Reference Lee2005b; Lee and Lee Reference Lee and Lee2011; Moon Reference Moon2011; Park Reference Park2014; Seo and Park Reference Seo and Park2009).

When it comes to party discipline, the existing literature (e.g. Choi Reference Choi2006; Han Reference Han2013; Lee and Lee Reference Lee and Lee2011; Seo and Park Reference Seo and Park2009) indicates that legislators’ party membership still controls their legislative behaviour in Korea. Yet, recent studies (Jeon Reference Jeon2006; Lee Reference Lee2005a; Park and Jeon Reference Park and Jeon2015) reveal that constituents’ demands also play a role in shaping lawmakers’ roll-call voting. For instance, Lee (Reference Lee2005a) finds that lawmakers representing rural areas overwhelmingly opposed the Free Trade Agreement with Chile, regardless of their partisanship during the 16th National Assembly. Park and Jeon (Reference Park and Jeon2015) also show that lawmakers from metropolitan areas with large companies were in favour of bills to reduce the level of corporate taxes in both the 18th and 19th National Assemblies. Indeed, Korean lawmakers seem to take into consideration more constituents’ interests than before in their roll-call voting decisions. More than a half of the Saenuri Party members and the Democratic United Party lawmakers voted against their party position or did not vote on the bills of acquisition tax cuts in the 19th National Assembly.Footnote 1 In this article, we seek to find out which members of the National Assembly in Korea respond to the problem of income inequality and what makes them responsive to constituents’ interests.

INCOME INEQUALITY AND THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY

Korea’s political parties show different approaches to dealing with the issue of income inequality. In the 18th National Assembly, the Grand National Party (GNP), the major conservative party, and the United Democratic Party, the major liberal party, took ideologically distinctive stances regarding income inequality. During the 17th National Assembly, the Open Uri Party, the majority and ruling party, led liberal legislation.Footnote 2 Yet, after the Grand National Party took the majority position in the 18th National Assembly (2008–12), liberal policies were generally reversed. The Lee administration, which officially began on 25 February 2008, also demonstrated a conservative and business-friendly inclination. By accident or design, the first bill introduced in the 18th National Assembly was a revision of the Comprehensive Real Estate Holding Tax by Hye-hoon Lee (GNP).Footnote 3 This revision proposed reducing taxes for property owners.

The Comprehensive Real Estate Holding Tax was a part of the comprehensive real estate policy which was established under Roh’s liberal administration. It was an income-redistributive policy that aimed to regulate real estate speculation and increase taxes for those who possessed an excessive number of properties. President Roh first proposed the policy in 2003, and the Open Uri Party, the majority party in the 17th Assembly, passed it in 2005. Conservatives criticized the policy as a populist idea and called for revisions. On 14 January 2008, President-elect Lee announced that he planned to review the policy and reduce taxes for house owners. Responding to the president, the Grand National Party, the majority party in the 18th Assembly, passed the revision on 12 December 2008. Table 1 summarizes and compares the policies.

Income inequality is one of the traditional party-defining issues in capitalist countries (Hill and Hurley Reference Hill and Hurley1999). Conflicts between the conservative and liberal parties regarding income redistribution and welfare policies were intense during the 18th Assembly. Like President Roh and the Open Uri Party, President Lee and the Grand National Party enacted multiple policies according to their partisan interests.

Though income inequality is a party-defining issue, lawmakers cannot simply ignore their constituents’ preferences. In order to earn more votes, political parties and lawmakers sometimes disguise their ideological preferences. In fact, just before the 29 April by-election in 2009, Jun-pyo Hong, the GNP majority leader, declared that his party would not support the government’s policy to abolish heavy taxes on families who own three or more houses. Conservative media outlets attacked the Grand National Party, claiming that ‘the conservative party changed the reduced tax plan because they were influenced by populism’.Footnote 4

Especially notable was the 2010 local elections. At that time, conservatives and liberals had waged a life-or-death battle with welfare policies. The major conservative and liberal parties proposed policies for free school meals during the campaign. The Grand National Party proposed selective benefits for poor students, but the liberal coalition led by the United Democratic Party argued for universal benefits for all students. The coalition won more seats in the election. Since then, the conservatives have attempted to transform their image as ‘the party of the rich’. One year before the 18th presidential election, Geun-hye Park, a leading conservative presidential candidate, proposed a bill that aimed to expand welfare programmes.Footnote 5 In response to the bill, the opposition party members strongly criticized her, saying it ran counter to her own political ideology as well as that of her party (Institute for Democracy and Politics 2011).

Regarding the issue of inequality, it is worth mentioning a referendum on free school meals by Seoul Mayor Se-hoon Oh (GNP) in 2011. The Grand National Party and the United Democratic Party had an intense confrontation over the issue of free school meals: selective benefits vs. universal benefits.Footnote 6 During the debate, the Seoul Metropolitan Council controlled by the United Democratic Party voted for an ordinance giving free school meals to pupils. However, Mayor Oh opposed this ordinance and called for a referendum on the full enforcement of free school meals. Furthermore, Mayor Oh announced that he would resign if the ordinance was not altered by the referendum. Liberals campaigned for people to abstain from voting because if the referendum foundered, the ordinance would come into effect (the turnout threshold for an effective referendum is 33.3 per cent in Korea).

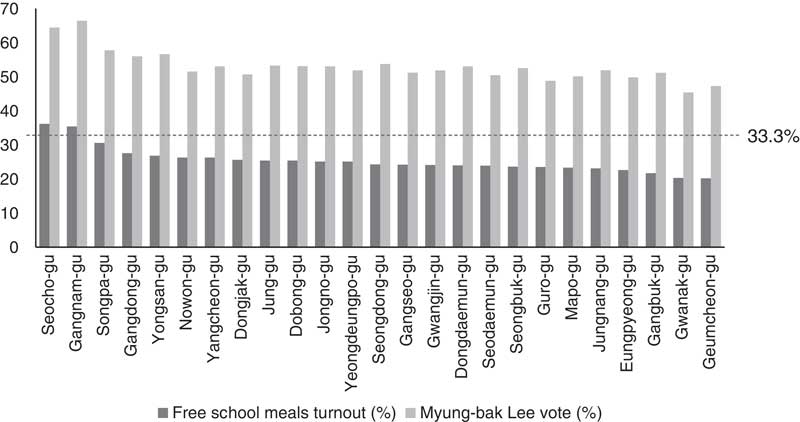

The referendum (24 August 2011) foundered because the turnout rate was 25.7 per cent. Interestingly, only two main gus (boroughs) in the Gangnam area (Seocho-gu, Gangnam-gu) registered a turnout of 36.2 and 35.4 per cent, higher than the threshold. These two Gangnam gus have a higher concentration of high-income residents and overwhelmingly support conservative parties, such as the Grand National Party. In fact, the two Gangnam gus are where Lee (GNP) received the highest vote share in the 17th presidential election (Figure 1).Footnote 7

Figure 1 Seoul Citizens’ Voting Behaviour

Figure 1 illustrates the Korean citizenry’s tendency to vote for candidates according to their policy preferences and economic interests. When representatives recognize this fact and seek re-election, they are more likely to respond to their constituents’ policy preferences and economic interests. However, it is also important to note that regional votingFootnote 8 can be influential in certain regions in Korea and affect legislative behaviour (e.g. Moon Reference Moon2009; Shin and Lee Reference Shin and Lee2015). Thus, we estimate constituency effects in lawmakers’ co-sponsorship behaviours while considering regional voting.

DATA

The Dependent Variable

We postulate that representatives respond to their constituents’ interests. In order to test the argument, this study explores Korean legislators’ sponsorship/co-sponsorship behaviours related to income inequality. More specifically, we examine who co-sponsors more bills that can increase or decrease income inequality. Accordingly, it is necessary to select bills related to income inequality.

Scholars, including Bartels (Reference Bartels2008) and Piketty (Reference Piketty2014), claim that some policy measures can reduce income inequality. One such measure is redistribution policy. For instance, a progressive tax can enhance income equality more than a flat-rate tax. If a bill intends to increase taxes for the rich and/or reduce taxes for the poor, it can be categorized as an income-equality bill. Another measure that can alleviate income inequality is welfare policy. Some bills aim to provide economic aid to low-income families.Footnote 9 These policy proposals can be considered to be income-equality bills.

Policies can amplify income inequality. For instance, property and estate taxes are generally levied on people who possess more properties. Reducing these taxes could increase economic inequality, and vice versa (Bartels Reference Bartels2008). Also, cutting corporate taxes could raise the level of income inequality (Piketty Reference Piketty2003). Some scholars point out that economic policies favourable to big businesses tend to contribute to economic polarization in Korea (e.g. Kang Reference Kang2002; Park Reference Park2003). Proposals that aim to reduce welfare programmes for low-income families are considered income-inequality bills (for more criteria, see the Appendix).

Based on these criteria, we searched for bills that could increase or decrease income inequality during the 18th Korean National Assembly.Footnote 10 Then we coded some of the bills as the income-equality bills that can alleviate income inequality and others as the income-inequality bills that can amplify income inequality. The number of income-equality bills is 95 and the number of income-inequality bills 32.

The dependent variable is the count of co-sponsorship by individual lawmakers in the National Assembly. Sponsorship and co-sponsorship are not treated differently. In the Korean National Assembly, at least nine co-sponsors with one sponsor are required to introduce a bill. Sponsors bear more responsibility for their proposals. However, it is difficult to assert that only sponsors are responsible for drafting and introducing bills. Certainly, there are some insignificant co-sponsors. Yet, as long as a relatively large number of bills are analysed, and insignificant co-sponsors are not systematically added, the test results in the following analyses are likely to be unbiased.

Independent Variables

In order to understand the interests of the electorate, we use the constituents’ voting behaviour in the prior election.Footnote 11 Research on voting behaviour in Korea (e.g. Moon Reference Moon2009) finds that citizens vote for candidates according to their ideologies. Ideology is closely related to policy preference (e.g. Erickson and Tedin Reference Erickson and Tedin2011; Lee and Kwon Reference Lee and Kwon2009). If a conservative candidate receives more votes in a district, it implies that the policy preferences of the electorate in this district are relatively more conservative. In measuring the ideological preferences of the electorate, we use the vote share information for the major conservative candidate by district in the 2007 presidential election.Footnote 12 According to our argument, as the vote share of the conservative presidential candidate increases, representatives will tend to co-sponsor more bills that can decrease income inequality, and fewer bills that will increase inequality.

Another constituency variable is related to the economic conditions of the electorate. This study considers that voters’ economic conditions are associated with their policy preferences. For instance, the poor are more likely to prefer policies that can reduce income inequality in general. We argue that if the proportion of the poor in a district is higher, a lawmaker tends to co-sponsor more bills that can decrease income inequality. To measure the proportion of the poor in a district, we utilize the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s classification of low-income families. The ministry classifies low-income families based on the minimum cost of living. If family incomes are lower than the minimum cost of living, those families are considered low-income families. We measure the proportion of the poor as the percentage of low-income families in a district.Footnote 13

The proportion of college graduates in a district is also included as another constituency variable.Footnote 14 According to the existing research (e.g. Moon Reference Moon2009), it is uncertain whether the educated prefer more liberal or conservative policies in Korea. Rather, the proportion of college graduates is likely to be linked to the economic conditions in a district. In Korea, higher education is one of the prerequisites for well-paying, professional occupations.Footnote 15 Hence, we hypothesize that representatives from districts with more educated citizens are less likely to co-sponsor bills that can reduce income inequality, and more likely to co-sponsor bills that will increase inequality.

Some scholars claim that political participation affects policymaking. For instance, representatives tend to make policies that can benefit politically active citizens (Hicks and Swank Reference Hicks and Swank1992). In particular, according to Hill and Leighley (Reference Hill and Leighley1992), higher voter turnout rates are associated with higher welfare expenditures. Generally, the rich are more likely to turn out than the poor in developed countries (Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). In other words, high voter turnout rates imply that the poor actively participate in elections and politics. Responding to high turnout rates, representatives tend to produce more policies that can benefit the poor. This study measures voter turnout rates (%) at the district level.Footnote 16

Related to election results, electoral competitiveness can affect legislators’ behaviour. A representative who wins an electoral landslide tends to regard the victory as a policy mandate and propose more partisan bills rather than respond to constituency interests. In contrast, lawmakers from competitive districts must pay more attention to their electoral fortunes in the coming election, which leads them to respond more actively to constituency interests. This study measures vote margin as the difference in vote share (%) between the winner and runner-up by district in the prior congressional election.

Control Variables

Besides the main independent variables, multiple factors can affect legislators’ behaviour. Firstly, party membership can explain lawmakers’ legislative activities. In the 2008 congressional election, the Grand National Party won 153 seats, and the United Democratic Party earned 81 seats. Four minor parties won at least one seat in the election.Footnote 17 As discussed previously, members from conservative parties are less likely to sponsor income equality bills. The Grand National Party and other minor conservative parties are coded as 1, otherwise 0.Footnote 18 Independents are controlled as a dummy variable. Thus, in the following regression analysis, the reference is liberal parties, including the United Democratic Party.

Representatives’ policy interests can affect their legislative behaviour. For instance, legislators who sit on standing committees that mainly discuss social programmes tend to co-sponsor more bills that can reduce income inequality. We focus on four standing committees that mainly deal with social policies.Footnote 19 The committee membership variable is measured as the frequency of sitting on these committees.Footnote 20 As Korean lawmakers become more senior, they tend to focus on issues of national security and unification. In fact, more senior members prefer to sit on committees that deal with national security and unification (Ka Reference Ka2009). Also, compared to juniors, seniors tend to propose fewer bills in general (Jeong and Chang Reference Jeong and Chang2013). We measure seniority as the number of terms that lawmakers have served.

RESULTS

This research constructs two scores to examine who co-sponsors bills that can affect income inequality and investigates constituency effects on lawmakers’ legislative behaviour. One score is the frequency of co-sponsoring bills that can decrease income inequality. The other variable is the frequency of co-sponsoring bills that can increase income inequality. In order to analyse the count measures, we utilize the Negative Binomial regression model.Footnote 21 The following tables report the regression results.

Table 1 The Comprehensive Real Estate Holding Tax: A Comparison of the 17th and 18th National Assembly

The findings in Table 2 show that a conservative candidate’s vote share in the previous presidential election significantly influences the lawmaker’s co-sponsorship behaviour. According to the results of Model 1-1 and Model 1-3, lawmakers tend to co-sponsor approximately 2 per cent fewer equality bills as the vote share for the conservative presidential candidate increases by 1 per cent.Footnote 22 If the vote share reflects the ideological and policy preferences of the electorate, the results imply that members of the Assembly respond to their constituents’ ideological preferences. In fact, some representatives from the conservative parties co-sponsored more bills that can alleviate income inequality in the 18th National Assembly. A member (GNP) from the Dobong district in Seoul co-sponsored 11 income-related bills; all of them were to reduce income inequality. Another GNP member from the Nowon district in Seoul co-sponsored 10 income-related bills, and nine of them were income-equality bills. Dobong and Nowon are the poorest areas in Seoul.Footnote 23

Table 2 Co-sponsorship of Income Equality Bills

Note: The numbers are the negative binomial regression coefficients, standard errors are in parentheses, and incidence rate ratios are in square brackets. The dependent variable is the frequency of co-sponsoring bills that can increase income equality. LR(α = 0): Likelihood-ratio chi-square test of α (dispersion parameter) = 0 (corresponding p-values are in parentheses). AIC: Akaike information criterion. Statistical significance: * <0.10, ** <0.05.

Other constituency variables in Model 1-1 and Model 1-3 do not significantly explain the dependent variable except the Turnout Rate variable in the last column.Footnote 24 We consider that higher voter turnout rates mean that voters, particularly the poor, are interested in politics. The findings generally support the argument of constituency effects and policy representation (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Leighley and Hinton-Andersson1995; Hill and Hurley Reference Hill and Hurley1999).

To examine constituency effects, this study controls for various influences on legislative behaviour. First, the results in the table show that party membership significantly explains Korean lawmakers’ co-sponsorship behaviour, which is consistent with previous research (Lee Reference Lee2005b; Lee and Lee Reference Lee and Lee2011). According to the results from the comprehensive model, representatives from the Grand National Party and other conservative parties tend to co-sponsor about 58 per cent fewer income equality bills. The results support the argument that conservative parties are less supportive of policies that increase income equality.

Model 1-2 examines the effects of legislators’ personal interests on their behaviour.Footnote 25 The Committee variable is statistically significant in the second and third models. That is, if legislators are more frequently assigned to the standing committees that deliberate social programmes, they tend to co-sponsor relatively more bills that can enhance income equality. We consider that committee membership can reflect lawmakers’ policy interests (e.g. Ka Reference Ka2009; Oleszek Reference Oleszek2014). The results show that legislators’ policy interests affect their co-sponsorship behaviour.

Another interesting variable is seniority. According to the results in Table 2, senior lawmakers generally co-sponsor fewer equality bills. The findings may mean that senior members are generally more conservative regarding the issue of income inequality. On the contrary, these results can be produced simply because seniors co-sponsor fewer bills in general (Jeong and Chang Reference Jeong and Chang2013).

Co-sponsoring income equality versus inequality bills can be distinctive. Hence, we code income-equality bills and income-inequality bills separately. The dependent variable in Table 3 is the frequency of co-sponsoring income inequality bills. The results in Table 3 are somewhat different from the outcomes in Table 2. For instance, the Presidential Votes variable is noticeable. According to the outcomes from Model 2-1, lawmakers tend to introduce about 1 per cent more income inequality bills when the conservative presidential candidate receives 1 per cent more popular votes in their districts.Footnote 26 However, the variable is statistically insignificant in the last column. That is, when the influences of control variables are considered, the effects of voters’ ideological preferences on co-sponsoring inequality bills tend to be minimized.

Table 3 Co-sponsorship of Income Inequality Bills

Note: The numbers are the negative binomial regression coefficients, standard errors are in parentheses, and incidence rate ratios are in square brackets. The dependent variable is the frequency of co-sponsoring bills that can increase income inequality. LR(α = 0): Likelihood-ratio chi-square test of α (dispersion parameter) = 0 (corresponding p-values are in parentheses). AIC: Akaike information criterion. Statistical significance: * <0.10, ** <0.05.

In Table 2, we reveal that voter turnout rates positively influence co-sponsoring income-equality bills. Similarly, lawmakers are less likely to co-sponsor inequality bills if their constituents actively turn out to vote. According to the results in Table 3, members of congress tend to co-sponsor about 3 per cent fewer inequality bills as the turnout rate increases by 1 per cent. The findings imply that representatives pay attention to who turns out to vote in their districts and respond to them.

The proportion of college graduates in a district significantly explains representatives’ co-sponsorship behaviours in Table 3. Lawmakers from districts where relatively more voters have bachelor’s degrees tend to co-sponsor more bills that can increase income inequality. If the variable is associated with the economic conditions in a district, the outcomes mean that lawmakers from relatively rich districts tend to introduce more income-inequality bills.Footnote 27

The control variables show similar effects in Table 3. For instance, legislators from the conservative parties tend to co-sponsor more bills that can increase income inequality. However, unlike the results in Table 2, the Committee variable is insignificant in Table 3. That is, although lawmakers who are interested in social policies tend to co-sponsor more equality bills, they do not co-sponsor more or fewer inequality bills than others. The Seniority variable is also statistically significant, but the sign is negative in Table 3. Senior members are less likely to co-sponsor income equality and inequality bills. That is, senior members are less active in proposing bills rather than being more conservative or liberal in general.

CONCLUSION

Economic inequality is a buzzword in the global economy, and Korea is no exception. Although the World Bank reports that ‘Korea has experienced remarkable success in combining rapid economic growth with significant reductions in poverty’, the world’s fifteenth largest economy in 2015 is also struggling with a growing problem of economic inequality.Footnote 28 Korea’s Gini Index has been degenerating at the fifth-fastest rate among 28 Asian economies over the past 20 years (ADB report), and income inequality worsened by 0.9 per cent on average per year from 1990 to 2010.Footnote 29

Indeed, income inequality is regarded as one of the most controversial issues in the Korean National Assembly. Liberal political parties are at odds with conservative parties over the issue of income inequality, as they share little in how best to respond. Obviously, issues of government taxation, the government’s market intervention and redistributive policy are always at the heart of political conflicts. In Korea, conservative parties are in favour of promoting business investment through curbing corporate taxes and market regulations. Liberal parties, on the other hand, call for protective regulatory policies for workers and consumers, as well as for a social safety net and income redistribution for the economically disadvantaged.

In this article, we have investigated whether and how lawmakers in Korea respond to their constituents’ interests. In particular, this study focuses on lawmakers’ co-sponsorship behaviour regarding income inequality. The empirical findings show that Korean lawmakers tend to respond to the ideological preferences of their constituents, as evidenced in the literature on democratic representation (e.g. Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963; Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010). To be specific, representatives from more conservative districts tend to co-sponsor fewer bills intended to reduce income inequality, and vice versa. Also, this study notes the link between election results and legislative behaviour. In other words, the more voters turn out to vote, the more redistributive bills legislators tend to co-sponsor. Finally, the proportion of college graduates in districts positively affects lawmakers’ co-sponsorship activities towards income inequality bills. In sum, the findings in this article support the argument that legislators respond to their constituents in Korea.

Voters in Korea are increasingly concerned about the legislative response to income inequality. The constituency realizes the importance of their representatives’ activities in guiding their economic conditions. Also, lawmakers in Korea do not always defer to their party leadership. Korean representatives, in particular, tend to respond to their constituents in co-sponsoring bills related to the interests of their constituents. This may signal that Korean democracy is consolidating to represent the people, not just the elites. As the question of economic inequality often ends up being a political, social and even generational problem, further research is warranted to discover the connection between the represented and their representatives.

APPENDIX

Coding rules: income-equality bills contain the following:

-

♦ More progressive taxation

-

♦ Increasing property taxes

-

♦ Increasing estate taxes

-

♦ Increasing gift taxes

-

♦ Increasing corporation taxes

-

♦ Reducing taxes for small businesses

-

♦ Reducing taxes for low-income families

-

♦ Increasing welfare spending for low-income families (such as scholarships for students from low-income families)

-

♦ Expanding welfare programmes for low-income families (for instance, lowering the levels for receiving welfare benefits)

-

♦ Increasing welfare spending for the unemployed

-

♦ Increasing the minimum wage

Coding rules: income-inequality bills contain the following:

-

♦ Less progressive taxation

-

♦ Reducing property taxes

-

♦ Reducing estate taxes

-

♦ Reducing gift taxes

-

♦ Reducing corporation taxes

-

♦ Increasing taxes for small businesses

-

♦ Increasing taxes for low-income families

-

♦ Reducing welfare spending for low-income families (such as scholarships for students from low-income families)

-

♦ Reducing welfare programmes for low-income families (for instance, increasing the levels for receiving welfare benefits)

-

♦ Reducing welfare spending for the unemployed

-

♦ Reducing the minimum wage

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2013S1A3A2054311 & NRF-2014S1A3A2044343).