After spending what he thought was a wasted day in the Mekong Delta with a US infantry unit that had made no contact with the enemy, CBS reporter Bert Quint filed his most important story about the Vietnam War. Quint at first feared that he had taken “a walk in the sun,” a term that correspondents used to describe a combat mission when nothing happens. But he resolved that after “sweating my balls off here for ten hours … I’m not going to come up with nothing.” Quint had been in Vietnam for only a few weeks, “but long enough,” he recalled, “to give me this feeling” that US strategy was “leading to nothing.”Footnote 1

That idea produced an unusual story on the CBS Evening News on August 8, 1967. Instead of a snapshot of a small part of the war, his report provided the “big picture,” something that Quint rarely tried to do. His theme was that the war was a stalemate. The lack of “bang, bang” or battlefield fighting in the film – a deficiency that often doomed a combat report – became an asset, since it revealed the frustration of US troops and the ineffectiveness of their strategy. “It’s a painful, foot-by-foot, paddy-by-paddy, stream-by-stream pursuit of an enemy that rarely stands and fights,” Quint explained, “that prefers to hit and then run, make for sanctuary in Cambodia when the going gets too tough, regroup, infiltrate back into Vietnam, and then hit again.” In this war of attrition, Quint thought it was hard “to know which side would wear out first.” The “statements by American officials that there is no stalemate, that real progress is being made, ring hollow down here,” he concluded.Footnote 2

Quint’s story ran only a day after a front-page article in the New York Times also concluded that the war was a stalemate. The author was R. W. Apple, Jr., the newspaper’s Saigon bureau chief, and he described Vietnam as “the most frustrating conflict in American history.” “The war is not going well,” according to “most disinterested observers” to whom Apple spoke. Enemy military forces were larger than ever; only a small portion of South Vietnam was secure; and without US troops, the South Vietnamese government “would almost certainly crumble within months.” “Victory is not close at hand,” Apple declared. “It may be beyond reach.”Footnote 3 Appearing on consecutive days in major national news outlets, Apple’s and Quint’s stories helped make “stalemate” a prominent and troubling theme in the reporting from Vietnam during the middle of 1967.

President Lyndon B. Johnson considered these stories about stalemate examples of war reporting that was distorted, misleading, and sensationalized. He complained that journalists dwelled on the shortcomings of American strategy, the excesses of US soldiers and marines in battle, or the ineffectiveness of pacification programs. “Nothing is being written or published to make you hate the Viet Cong,” he declared in a cabinet meeting. “All that is being written is to hate us.” Johnson was uneasy that military censors did not have to approve news stories and film from Vietnam as they had from the battle zones of World War II and Korea. US information officials rejected censorship for practical reasons; it was impossible to control the reporting of a press corps that numbered more than 250 at the end of 1965 and that had swelled to almost 700 two years later. They also worried about jeopardizing popular support for US military intervention by appearing to conceal important information about the war. The president, however, had a sardonic explanation for the absence of mandatory censorship. His administration had adopted that policy “because we are fools.”Footnote 4

While President John F. Kennedy had also worried about critical news coverage that challenged his administration’s upbeat pronouncements about the war, Johnson often considered such stories to be personal attacks. He maintained that Quint’s report showed that Walter Cronkite, the anchor of the CBS Evening News, was out to “get” him.Footnote 5 He told a visiting group of Australian broadcasters that the news media presented a one-sided view of the war aimed at discrediting him. “I can prove that Ho [Chi Minh] is a son-of-a-bitch if you let me put it on the screen,” the president insisted, “but they want me to be the son-of-a-bitch.”Footnote 6 President Richard M. Nixon denounced the news media even more stridently. Nixon believed that he had “entered the Presidency with less support from major publications and TV networks than any President in history.”Footnote 7 He called Vietnam reporters “bastards” who were “trying to stick the knife right in our groin.”Footnote 8

The journalists who covered Vietnam were never as myopic or malicious as Johnson and Nixon maintained. Indeed, their reports often emphasized the power and effectiveness of US military operations and the benevolence of Americans toward Vietnamese civilians. Still, the news media aroused presidential anger because many stories – even those about US victories – showed that the war was difficult and deadly, success was elusive and ephemeral, and official US assessments of the fighting were unreliable or unduly optimistic. As polls showed declining popular support for the US war effort, it became easy and politically expedient for Johnson and Nixon to blame the news media – and especially the television networks – for public discontent. Like so many parts of the American experience in Vietnam, the news reporting of the war became a polarizing issue.

Early Battles

The war became a major story in the US news media in the early 1960s as fighting increased between the South Vietnamese armed forces (ARVN) and the National Liberation Front (NLF) and as the Kennedy administration boosted the number of US military personnel involved in the war from 900 to more than 16,000. In early 1962, the New York Times became the first US newspaper with a full-time correspondent in Vietnam when it sent veteran war reporter Homer Bigart to Saigon. Bigart joined a small group of journalists working for wire services and news magazines, including some who were a generation younger, and a few, such as Malcolm Browne of the Associated Press and Neil Sheehan of United Press International, who were just embarking on what became illustrious careers. Bigart’s articles contained scathing criticism of the South Vietnamese government and concluded that the United States was “inextricably committed to a long, inconclusive war.”Footnote 9

South Vietnamese president Ngô Đình Diệm fumed at such stories. He ordered the expulsion of Bigart and Newsweek stringer Francois Sully, another critic who minced no words. The US Embassy intervened on behalf of both journalists, although Ambassador Frederick Nolting probably disliked Bigart as much as Diệm did. Nolting, however, won reprieves for both reporters by arguing that deporting correspondents for two prominent US news publications could jeopardize public and congressional support for US aid to South Vietnam. When Bigart departed at the end of his assignment in July 1962, he published a wrap-up article in which he criticized South Vietnam’s “secretive, suspicious, dictatorial” rule and warned that the Kennedy administration might soon face the choice of “ditching” Diệm “for a military junta or sending troops to bolster his regime.”Footnote 10

The Kennedy administration preferred voluntary cooperation with reporters rather than coercive tactics to manage the news from Vietnam. A directive from Washington in February 1962 known as Cable 1006 established a set of guidelines aimed at encouraging journalists to report about the war in a manner that served “our national interest.” Particularly harmful were stories about US officers “leading and directing combat operations against the Viet Cong,” since Kennedy and his top aides wanted to maintain the fiction that Americans in uniform were no more than military advisors in a Vietnamese war. Also detrimental were stories about civilian casualties during military operations and “frivolous, thoughtless criticism” of the Diệm government. US officials should appeal to reporters in Vietnam to exercise self-restraint in these areas in the interest of national security. They should also provide correspondents with frequent briefings and transportation to battle areas, but exclude the news media from combat missions that were likely to produce unfavorable stories.Footnote 11

These guidelines only exacerbated tensions between reporters and US officials. Bigart bridled at the notion that reporters were tools of US foreign policy. Information officers lost credibility as their accounts of fighting contradicted what reporters saw in the field. An acrimonious dispute occurred in January 1963 over the battle of Ấp Bắc, when ARVN military forces allowed a vastly outnumbered NLF infantry battalion to escape from their attack. “A miserable damn performance,” complained one frustrated US military advisor about the squandered opportunity for a major victory.Footnote 12 That quotation appeared in several newspaper and magazine articles that variously described Ấp Bӑc as an example of South Vietnamese ineffectiveness, incompetence, or irresolution. To assuage Diệm’s anger over the torrent of media criticism, US commanders tried to spin Ấp Bӑc as a South Vietnamese victory since the enemy had fled the battlefield. Admiral Harry D. Felt, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific, even visited Saigon and admonished Browne, who had written about ARVN inadequacies at Ấp Bӑc, to “get on the team.”Footnote 13 The upshot of this controversy was widening distrust between senior American political and military officials in South Vietnam, who doubted the fairness and reliability of much of the war reporting, and Saigon journalists, who thought that official sources of information lacked credibility.

The disputes over war reporting intensified during the Buddhist crisis, which became a major story in June 1963 when both print and television news outlets showed shocking images of the fiery suicide of a Buddhist monk protesting government restrictions on public religious celebrations. Acting on a tipoff, Browne went to a busy Saigon intersection on June 11 and photographed Thích Quảng Đức as he burned himself to death. “I suppose that no news picture in recent history has generated as much emotion around the world,” President Kennedy remarked.Footnote 14 Mass protests followed in Saigon, as did government allegations that communists had inspired them. The crackdown continued with raids on Buddhist pagodas and the arrests of hundreds of alleged subversives.

As the disarray in Saigon worsened, a flurry of news stories questioned whether Diệm’s unpopularity was destroying his government’s chances of defeating the NLF. President Kennedy even delivered a version of that message to Diệm during interviews in September on the inaugural broadcasts of the CBS and NBC evening news programs as they expanded from fifteen to thirty minutes. “The repressions against the Buddhists … were very unwise,” Kennedy told Cronkite. “I don’t think that unless a greater effort is made by the government to win popular support that the war can be won out there.”Footnote 15 As Kennedy and his advisors discussed whether to encourage a coup against Diệm, the CIA scrutinized the reporting about the Buddhist crisis by David Halberstam, Bigart’s successor as the New York Times’s correspondent in Saigon and a frequent critic of the Diệm government. The CIA concluded that Halberstam’s articles were factually accurate but “invariably pessimistic” and at odds with the optimism of most US military officials in South Vietnam.Footnote 16

Kennedy had reservations about deposing Diệm, but he was certain that it was time for a change in the New York Times Saigon bureau. “Don’t you think he’s too close to the story?” the president asked about Halberstam in a White House meeting with Times publisher Arthur Ochs Sulzberger. “You weren’t thinking of transferring him to Paris or Rome?” Taken aback by the president’s suggestions, Sulzberger canceled Halberstam’s upcoming vacation lest it appear that the Times was yielding to White House pressure.Footnote 17

Charlie Mohr got no such support at Time magazine when he filed a story in September 1963 about how Diệm’s government was losing the war. Articles in Time did not appear under an author’s byline. The writers and editors in New York who composed the magazine’s uncredited pieces drew on information from correspondents’ reports, but often changed the perspective and tone to fit the political outlook of the magazine. In the early 1960s, Time reflected the views of founder and editor-in-chief Henry R. Luce, who was an admirer of Diệm and a supporter of Kennedy administration policies in Vietnam. Mohr had become accustomed to rewriting and editing that muted his sharp criticisms of the Diệm government. In this instance, however, Mohr’s lengthy analysis of Diệm’s faltering war effort never appeared in an article that asserted that “government soldiers are fighting better than ever.” Time’s managing editor Otto Fuerbringer included in the same issue a critique of the Saigon press corps, an “inbred” club who “pool their convictions, information, misinformation, and grievances” and turn “the complicated greys of a complicated country … into oversimplified blacks and whites.”Footnote 18 Mohr decided that he would no longer be a target for a magazine “shelling its own troops.”Footnote 19 He quit and began working for the New York Times.

The reporting of Mohr, Halberstam, Browne, and Sheehan created doubts in US newsrooms, consternation in the US Embassy in Saigon, and outrage in the South Vietnamese presidential palace. Prominent journalists who were optimistic about the war reinforced these critical reactions. Marguerite Higgins, a Pulitzer Prize winner for her coverage of the Korean War and a correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune, toured South Vietnam in July 1963 and found that “the war is going better than ever.” She also impugned the motives of the Saigon reporters, alleging that they “would like to see us lose the war to prove they’re right.”Footnote 20 Joseph Alsop, a leading syndicated columnist, visited Vietnam shortly after Higgins and also concluded that the war was going “remarkably well” in the countryside.Footnote 21 He blamed the “young crusaders” of the Saigon press corps for the government’s current problems. Their dark, foreboding stories had helped “to transform Diệm from a courageous, quite viable national leader, into a man afflicted with galloping persecution mania … and therefore misjudging everything.”Footnote 22 There is no doubt that Mohr, Halberstam, Sheehan, and Browne were convinced that the Diệm government had severe, even fatal, liabilities. What Higgins, Alsop, and Fuerbringer failed to understand was that these “young crusaders” were not opponents of the war, as they never questioned the goal of halting communist expansion in Southeast Asia. They wanted stronger US action to invigorate the South Vietnamese war effort. Their reporting and the backlash against it created what Halberstam called “a war within a war,” which continued after the coup against Diệm, the assassination of Kennedy, and the arrival of many new reporters in South Vietnam.Footnote 23

Escalation

As the Johnson administration escalated US combat involvement in 1964–5, the news media expanded their coverage of the war. At the beginning of 1964, there were about forty reporters in Saigon. By the end of 1965, that number had increased more than sixfold. The three major weekly news magazines – Time, Newsweek, and US News & World Report – enlarged their Saigon staffs and published many articles with news about the war, especially US military operations. Several major newspapers, including the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Baltimore Sun, and Christian Science Monitor, also sent reporters or established news bureaus in Saigon. In July 1964, Garrick Utley of NBC became the first full-time television correspondent based in Saigon; Morley Safer of CBS was the second in January 1965. NBC and CBS usually had a larger contingent of reporters in South Vietnam than ABC, which was last in the ratings and waited until January 1967 to expand its evening newscast to thirty minutes. By 1967, however, all three networks were spending more than $1 million each year, then a substantial sum, on their Vietnam news coverage.

Hoping to make a fresh start at restoring their credibility, US officials once more rejected news censorship in favor of a new operating principle – “maximum candor and disclosure consistent with security considerations.”Footnote 24 Candor, however, was often at a minimum. For example, during a visit to Saigon, the assistant secretary of defense for public affairs, Arthur Sylvester, told Saigon correspondents, “Look, if you think that any American official is going to tell you the truth, you’re stupid.” His remark reflected a belief that the news media should be the “handmaiden” of government in wartime.Footnote 25 Sylvester’s comment made some reporters indignant. Others scoffed at the official daily briefings about the war, which they called “the five o’clock follies” because those presentations suffered from half-truths, inaccuracies, and omissions.

The problems with candor reached all the way to the White House, as Johnson tried to divert attention from the expanding US military role in South Vietnam. The president even maintained that the major increase in US troop strength that he announced on July 28, 1965, implied no change in policy whatsoever. Johnson, however, found that his legendary powers of persuasion could not stifle criticism from some highly influential newspaper columnists. Arthur Krock of the New York Times disparaged the administration’s “evasive rhetoric” aimed at disguising “a fundamental change” in the mission of US troops.Footnote 26 The president’s assiduous cultivation did not prevent syndicated political commentator Walter Lippmann, the most influential columnist of all, from objecting to US involvement in a major land war in Asia that he considered neither wise nor winnable. The president was so embittered that he angrily referred to such columnists as “whores.”Footnote 27

Johnson was even more concerned about television coverage of the war. Vietnam was the United States’ first television war, the first time that a majority of the American people relied primarily on TV for news about US troops in battle. Polls showed that the public considered TV the most believable news medium. It inspired such trust because of its ability to transmit experience. A newspaper or magazine could recount a search-and-destroy mission; TV could show the courage of soldiers or the fears of displaced villagers. Johnson worried about the emotional power of television film reports and the simplification inherent in stories that were usually no longer than three minutes.

A story in August 1965 from Cẩm Nê confirmed the president’s apprehensions. Morley Safer accompanied a battalion of US marines on a search-and-destroy mission in Cẩm Nê, a village south of Đà Nẵng that was supposed to be an enemy stronghold. The marines encountered some sniper fire, but they found only old men, women, and children when they entered Cẩm Nê. According to Safer, an officer said the battalion had orders to level the village. What made Safer’s story sensational was film of one marine using a cigarette lighter and another a flamethrower to burn down thatched huts as terrified peasants watched in disbelief. “Today’s operation is the frustration of Vietnam in miniature,” Safer asserted as he closed his report. “There is little doubt that American firepower can win a military victory here. But to a Vietnamese peasant whose home means a lifetime of backbreaking labor, it will take more than presidential promises to convince him that we are on his side.”Footnote 28

Johnson was infuriated. He telephoned Frank Stanton, the president of CBS, and began the conversation by asking, “Are you trying to fuck me?”Footnote 29 The president thought that Safer must be a communist, but investigations could find no more damning information than that the reporter was a Canadian. Sylvester pressed CBS to replace Safer with an American reporter who could provide more sympathetic coverage, but CBS resisted.

Safer’s Cẩm Nê report created a furor, but it also raised fundamental questions about US military operations. Some administration officials recognized that there would be more stories like Safer’s as long as US forces burned villages. A new directive from the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) required greater restraint in future operations in civilian areas. The marines even tried to make amends by returning to Cẩm Nê and rebuilding the village, a story that Safer covered. Administration officials, however, still worried about what they called the information problem and how to deal with “fighting out in the open” in “a new kind of twilight war.”Footnote 30 So, too, did the president, who fretted about how negative reporting like Safer’s or hostile columnists might influence public support for his Vietnam policies. While there was no immediate problem, Johnson predicted that difficulties could arise if the war lasted more than a year.

Another sensational challenge to US war policies occurred when Harrison Salisbury, the assistant managing editor of the New York Times, became the first journalist from a major Western news organization to report from North Vietnam. Salisbury’s first dispatch from behind enemy lines appeared on the front page of the Times as well as in dozens of other US and international newspapers on December 26, 1966. Twenty additional articles followed during the next three weeks. The main reason that his reports attracted wide attention was because they challenged the Johnson administration’s assertions that the bombing of the North was effective and that it damaged, with few exceptions, only military targets. The “ground-level reality” along Route 1, a major road that ran south from Hanoi, and an adjacent railway showed that heavy US bombing had not disrupted the movement of people and supplies. At Nam Định, Salisbury found no military targets, yet “block after block of utter devastation.”Footnote 31

These assertions as well as others about civilian casualties caused an uproar. Critics who doubted the accuracy or effectiveness of the bombing found validation in Salisbury’s on-the-ground observations. The Pentagon replied with a statement that US planes struck only military targets, although it was “impossible to avoid all damage to civilian areas.”Footnote 32 Salisbury faced fierce criticism from other journalists for belatedly revealing that he had relied on a North Vietnamese propaganda pamphlet for casualty figures. Yet this source was more reliable than Salisbury’s critics ever imagined. The pamphlet, like Salisbury, failed to mention that there were indeed military targets in Nam Định, including a power plant and petroleum storage facility. A secret CIA study, however, confirmed the accuracy of the pamphlet’s statistics about damage to residential areas and civilian casualties.Footnote 33 Critics deprecated Salisbury as a mouthpiece for Hanoi, but even Philip Goulding, the deputy assistant secretary of defense for public affairs, conceded that his reporting had damaged administration credibility.

Salisbury’s and Safer’s critical stories were exceptional. More common during 1965–6 were reports about US success in Vietnam. Television journalists often emphasized the bravery of American troops and their superior firepower. News magazines also provided upbeat assessments. Even the most liberal of the three major news magazines, Newsweek, supported Johnson’s decision to fight in Vietnam. US News & World Report offered the most conservative perspectives, emphasizing the need to halt the spread of communism in Southeast Asia and maintaining that the greatest obstacle to victory was White House restraint in the use of force. Television and print journalists commonly referred to “our” troops, ships, and planes and often called the enemy the “Communists” or the “Reds.”

Even though Johnson and his aides complained frequently about hostile reporting, there were many journalists who supported US policies in Vietnam. While Lippmann decried Johnson’s “messianic megalomania,” Alsop applauded the president’s “drive and imagination.”Footnote 34 On television, there was little room for commentary on network newscasts because of the prevailing standards of objective journalism, including fairness, impartiality, and balance. News anchors, however, did occasionally express their personal views and usually favored administration policies. For example, ABC anchor Howard K. Smith hosted a special, prime-time broadcast in July 1966 and declared, “It is entirely good what we’re doing in Vietnam.”Footnote 35

Johnson, however, did not find balance or diversity in such commentary or in the news media’s reporting of the war. He seemed to notice only those stories that showed US difficulties in battle or problems in pacification. “On NBC today it was all about what we are doing wrong,” Johnson declared in December 1965. “The Viet Cong atrocities never get publicized.”Footnote 36 Yet the ABC and CBS newscasts that evening included stories about an enemy “terrorist” attack on US troops in Saigon.Footnote 37 Johnson’s denunciations of the news media became increasingly vituperative. In March 1967, LBJ made the fantastic claim that CBS and NBC were “controlled by the Viet Cong.”Footnote 38 The president also charged that NBC and the New York Times were “committed to an editorial policy of making us surrender.”Footnote 39

Progress or Stalemate?

Johnson’s concern about media reporting became more urgent as the news from Vietnam grew bleaker in mid-1967. In July, NBC’s Howard Tuckner filed a discouraging report from Cẩm Nê, the location of Safer’s sensational story two years earlier. The South Vietnamese government had decided to destroy the village rather than defend it and moved its residents to a desolate “peace hamlet,” which one US worker described as a “concentration camp.” There were frequent stories about fierce fighting and heavy US losses near the demilitarized zone. Then Quint’s and Apple’s stories described the war as a stalemate. Also in late summer, Time abruptly shifted its perspective on the war when editor-in-chief Hedley Donovan ordered his staff to abandon its role of “cheerleader” for administration policy. The result was a series of articles about a deadlocked but increasingly deadly war.Footnote 40

Once more, the president and his aides blamed hostile and antagonistic reporters for bleak news about the war. After the publication of the New York Times’s stalemate story, the president charged that Apple was a communist. Leonard Marks, the director of the US Information Agency, did not make such extreme allegations but informed Johnson that during a recent trip to Vietnam he had found that reporters had brought to their assignments “built-in doubts and reservations” and were searching “for the critical story which might lead to a Pulitzer Prize.”Footnote 41 Such comments reinforced the president’s conviction that the hostility of the news media was an important reason for sagging poll numbers. As Johnson had anticipated, public opinion became a problem as the war claimed lives and treasure at an increasing rate, yet with no end in sight. By August, polls showed that only one-third of the American people supported the president’s handling of the war. With public discontent so strong and an election year approaching, Johnson knew he had to reclaim public support. The result was a new public relations effort called the Progress Campaign.

Johnson urged his aides to “get a better story to the American people.”Footnote 42 With the help of a new Vietnam Information Group, the administration leaked reports about progress in the war to friendly journalists and prepared upbeat speeches for sympathetic members of Congress. “We have got to sell our product to the American people,” Johnson declared.Footnote 43 The president did just that. He met with business leaders, educators, and union officials and was emphatic and insistent in denying that the war was a stalemate. At a televised news conference in November, he affirmed with words and gestures that the prospects for success in the war were rising. A few days later, General William Westmoreland, the commander of US forces in Vietnam, added his voice to the chorus of optimism while delivering a speech at the National Press Club in Washington, DC, in which he asserted that “we have reached an important point when the end begins to come into view.”Footnote 44 The news media gave these high-profile presentations a good deal of favorable coverage. US News & World Report ran two articles in the same issue, one from Washington – “Vietnam: War Tide Turning to US”– and another from Saigon, “The Coin Has Flipped to Our Side.”Footnote 45 Such stories were important because the president believed that “the main front of the war was here in the United States.”Footnote 46

There were also challenges in the news media to the president’s assurances of progress. In a rare editorial, Life magazine advocated a bombing pause, arguing that it would recoup domestic and international support for the administration’s “glaringly unsuccessful” war policies.Footnote 47 Heavy fighting at Đӑk Tô, which claimed more US lives than any previous battle, got extensive and sometimes skeptical coverage. “It was a hard fight,” ABC’s Ed Needham observed in closing his report. “It hardly seemed worth it.”Footnote 48 CBS aired John Laurence’s poignant story about a skirmish near Hội An that claimed the life of a young American soldier with red hair and freckles. “There are a hundred platoons fighting a hundred small battles in nameless hamlets like this every week of the war,” Laurence said. “They are called firefights. And in the grand strategy of things, this firefight had little meaning for anyone but the red-headed kid who was killed here.”Footnote 49 Laurence used the death of an unnamed soldier to show that the war no longer served any useful purpose.

By the end of 1967, the Progress Campaign had achieved some success. Polls showed that 50 percent of Americans thought US forces were making progress in the war compared to only 33 percent five months earlier. The discontent with Johnson’s Vietnam policies had also diminished, although critics still outnumbered supporters by a margin of 11 percentage points, 49 percent to 38 percent (with the remainder undecided). These improvements had occurred because the Progress Campaign had raised expectations of good news from Vietnam. Then came the Tet Offensive.

“What the Hell Is Going On?”

Tet became the war’s “big story,” in the apt phrase of Peter Braestrup, a Vietnam correspondent for the Washington Post. Fighting occurred almost everywhere – in major cities and rural hamlets from the demilitarized zone to the Mekong Delta. Attacks occurred on the US Embassy grounds and the South Vietnamese presidential palace. The war reporters could not possibly cover almost simultaneous attacks in more than 150 locations. They concentrated on the big battles that lasted the longest – the siege of the US base at Khe Sanh and the savage street fighting in Huế. The news media showed the war as it never had before – as stunning, brazen, ghastly, unpredictable violence on an unprecedented scale that overwhelmed all of South Vietnam. In Saigon, there were tanks in the streets, tactical airstrikes in residential neighborhoods, and civilians caught in deadly crossfire. On all three television networks there were disturbing scenes of correspondents or the members of their crews becoming casualties of the fighting they covered.

The most spectacular – and horrifying – image of the Tet Offensive was the summary execution of an NLF prisoner by the chief of the South Vietnamese National Police, General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan. NBC and ABC showed film of the shooting on their evening newscasts. Many more people, however, saw Eddie Adams’s photo of the moment of the death, which appeared on the front pages of newspapers around the world and became one of the most reproduced images in history. NBC’s John Chancellor called the execution “rough justice on a Saigon street.”Footnote 50 In contrast, Johnson’s national security advisor, Walt W. Rostow, thought that Loan might be “one of the heroes of the battle thus far.”Footnote 51 This powerful image of death became a convenient symbol that both critics and supporters of the war used to justify their positions.

The Progress Campaign became an early casualty of the Tet Offensive. The New York Times editorialized that the attacks “throw doubt on recent official American claims of progress.” Newsweek chided the Johnson administration for not providing “a realistic assessment of the situation in Vietnam.”Footnote 52 Johnson tried to rebut these criticisms by telling White House correspondents that the enemy had failed to achieve its principal goal of igniting a popular uprising against the Saigon government. Such confident assertions had limited effect. ABC’s Joseph C. Harsch bluntly declared that the Tet Offensive was “the exact opposite of what American leaders have for months been leading us to expect.” CBS’s Robert Schakne captured the prevailing mood of shock and uncertainty. “For Americans in South Vietnam,” he asserted, “the world turned upside down in the past week.”Footnote 53

Walter Cronkite was also bewildered by the first reports of the Tet Offensive. “What the hell is going on?” he asked in disbelief. “I thought we were winning the war.”Footnote 54 Cronkite went to Vietnam to make his own assessment, and he presented his conclusions in a special, prime-time broadcast in late February 1968. At the end of the program, he made a radical departure from his familiar role of impartial newscaster, hoping that his reputation as “the most trusted man in America” would make viewers willing to listen to his personal commentary at this critical moment. He explained that the frightful casualties, extensive destruction, and a staggering increase in refugees had not altered the pattern of the war. “To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion,” he declared. While it was difficult for Cronkite to determine who had won and who had lost, there was one clear casualty, the credibility of the president and his top military and political aides. “We have been too often disappointed by the optimism of the American leaders, both in Vietnam and Washington, to have faith any longer in the silver linings they find in the darkest clouds,” Cronkite asserted.Footnote 55 Johnson brooded over the broadcast. “If I’ve lost Cronkite,” he despaired, “I’ve lost the American people.”Footnote 56

The coverage of Tet, like earlier reporting of the war, generated controversy. One of the most prominent critics was Peter Braestrup, who argued in his encyclopedic analysis of the Tet Offensive that the news media got the “big story” wrong. “Essentially, the dominant themes of the words and film from Vietnam … added up to a portrait of defeat” for the United States and South Vietnam, Braestrup argued, even though historians “have concluded that the Tet offensive resulted in a severe military-political setback for Hanoi.”Footnote 57 Braestrup anticipated by more than three decades the analysis of historian Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, who found that Hanoi’s bold bid for decisive victory in 1968 had disastrous effects on North Vietnamese military and political strategy.Footnote 58 Journalists in February 1968 lacked the information and perspective of historians who wrote years later, but the best, like Cronkite, recognized that the enemy had suffered enormous losses, while still inflicting sharp blows on the perceptions of power in Saigon and Washington. What is striking is how closely Cronkite’s analysis resembled official US analyses, which emphasized the vulnerability of even the most secure locations in urban centers and the damage to rural pacification programs. For Cronkite, just as for most US officials in Saigon and Washington, the Tet Offensive had changed the war.

Johnson, too, criticized the coverage of Tet. In his memoirs, he deplored “the emotional and exaggerated reporting” that conveyed the impression “that we must have suffered a defeat.”Footnote 59 On the day after he announced that he would not seek another term as president, he kept a previously scheduled commitment to deliver a speech to the National Association of Broadcasters. No one, he declared, could be sure how televised scenes of fighting in Vietnam had affected public support for his administration’s policies, which then stood, according to the latest poll, at only 26 percent. He wondered aloud what influence television news, had it existed, might have had during earlier wars. Still, the president left no doubt that he believed that TV was responsible for the deep discontent with his war policies.

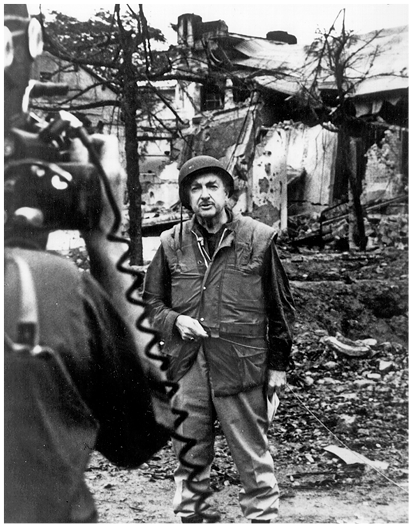

Figure 21.1 CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite covers the aftermath of the Tet Offensive for the special Report from Vietnam (1968).

“Our Worst Enemy Seems to Be the Press”

In its June 27, 1969, issue, Life magazine published photographs of the 242 Americans in uniform who had died during one week of fighting in Vietnam, the week that included the recent Memorial Day holiday. The weekly combat figures were part of the ritual of reporting the war. MACV provided no specific figures about losses in individual battles, characterizing them only as light, moderate, or heavy. Instead, it released weekly casualty reports. Each Thursday TV anchors read the figures on the evening newscasts, usually providing no additional information. According to the Life article, numbers were no longer enough. At a time when the war had claimed a total of 36,000 American lives and took 242 more in a single week, “we must pause to look into their faces.”Footnote 60 The article affected NBC news anchor David Brinkley, who departed from the usual recitation of numbers on the NBC evening newscast – the Huntley–Brinkley Report – only a few days later. Brinkley explained that, though the casualties “come out in the form of numbers, each one of them was a man, most of them quite young, each with hopes he will never realize, each with family and friends who will never see him alive again.”Footnote 61 Two weeks earlier, President Nixon had announced the withdrawal of 25,000 US troops from the war, the first step in what he called Vietnamization, or transferring combat responsibility to the ARVN. The troop withdrawal was also a way to mitigate public discontent with the war and the high weekly death tolls as Nixon searched for a way to win the peace, if not the war.

In his quest for what he eventually called peace with honor, Nixon considered the news media major antagonists. Like Johnson, he believed that journalists were out to “get” him. His allegations, however, were more vituperative and his methods for dealing with media opposition more vindictive. While House aides maintained lists of journalists arranged according to their friendliness or hostility. One compilation included only three television reporters in the category of “Generally for Us” while classifying twelve as “Generally Against” the administration.Footnote 62 These lists and the daily news summaries that aides prepared persuaded Nixon that a “solid majority” of journalists wanted “to bring us down.”Footnote 63 Nixon encouraged assistants to retaliate against individual journalists by cutting off their access to White House sources or complain to news organizations about unfair stories. He even threatened to use the powers of the Federal Communications Commission to intimidate the networks.

By the time he became president, Nixon thought that television mattered more than newspapers or magazines in influencing public opinion on Vietnam. His administration made several efforts to stoke popular discontent with TV news coverage as a way of deflecting discontent about the war from the White House to the networks. The most prominent figure in these antimedia campaigns was Vice President Spiro T. Agnew, who denounced network executives in November 1969 as “a tiny, enclosed fraternity” who deliberately skewed the news against the administration.Footnote 64 Agnew attracted considerable attention because of his flamboyant rhetoric and affection for alliteration, as in his notorious description of Nixon’s critics as “nattering nabobs of negativism.” Nixon, however, was always dissatisfied with the results of his aides’ efforts to bludgeon the news media into more favorable coverage of his Vietnam policies. He was upset, for example, with the news stories about the dispatch of US ground troops into Cambodia in April 1970. The president considered the Cambodian operation a “bold move” that showed the strength of his leadership. He complained that the news media dwelled instead on the campus protests against what seemed a dangerous enlargement of the war and the failure to locate the North Vietnamese command center, which was supposedly the main reason for sending US forces into Cambodia.

The animosity between the Nixon administration and the news media boiled over during Lam Sơn 719, a joint US–South Vietnamese military operation in Laos in March 1971 to cut the Hồ Chí Minh Trail and destroy North Vietnamese supply bases. Restrictions on air transportation kept many reporters stranded in rear staging areas. US commanders cited the dangers of enemy anti-aircraft fire. Reporters, who had braved hostile fire in many combat zones, wondered if US and South Vietnamese commanders were trying to keep them from covering the fighting. Nixon was anxious about a major test of Vietnamization since the ARVN was providing all the ground troops. He was adamant that “the operation cannot come out as a defeat.”Footnote 65 The film of wounded and weary South Vietnamese soldiers returning from battle areas on US helicopters after meeting heavy resistance certainly looked like a defeat on the network newscasts. “There wasn’t anything orderly or planned about getting these men out,” NBC correspondent Phil Brady, a former US marine, asserted. “They were overrun and defeated.”Footnote 66 Nixon was so furious that he charged that reporters wanted “the operation to fail since they oppose it and predicted it would fail.”Footnote 67 After Lam Sơn 719 ended, ABC devoted more than half of its evening newscast on April 1 to a discussion among its four main Vietnam reporters who criticized the Nixon administration for obstructing the news coverage of the Laos operation and trying to discredit their reporting about the ARVN’s poor performance. “We’ve been lied to so many times that you begin to suspect that no one ever tells you the truth,” correspondent Don Farmer declared.Footnote 68 Nixon, for his part, thought that during the whole operation “our worst enemy seems to be the press.”Footnote 69

As American troops came home from Vietnam, so did US reporters. Those who remained filed stories about subjects they had rarely, if ever, covered during the war’s early years, such as poor morale, combat refusals, and drug use. No story illustrated more dramatically how the experience of Vietnam had changed the US Army than Gary Shepard’s film report for the CBS Evening News about a unit of the 1st Cavalry that smoked marijuana from the barrel of a shotgun they called Ralph. As the soldiers inhaled, a squad leader named Vito acknowledged that the film might get them all “busted,” but then nonchalantly said, “I don’t care.”Footnote 70 By 1972, US ground combat troops had withdrawn, but the fighting continued between Vietnamese. CBS’s Bob Simon captured the agony of a war that had gone on far too long in a report about fighting in Quảng Trị province during the Easter Offensive in 1972. In the aftermath of battle, refugees became casualties when their vehicle struck a mine. The film showed children and babies scattered on the ground, “some … dead, some … not dead.” Simon wrapped up his story by declaring that there would be more fighting “and more words – words spoken by generals, journalists, politicians. But here on Route 1, it’s difficult to imagine what those words can be. There’s nothing left to say about this war. There’s just nothing left to say.”Footnote 71

Nixon did have more to say about Vietnam and the reporting of the war. He charged that journalists had “a vested interest in seeing the United States lose the war” and were “doing their desperate best to report all the bad news and to downplay all the good news.” Journalists had their own fears. Cronkite, for example, declared in a speech, “Many of us see clear indication on the part of this administration of a grand conspiracy to destroy the credibility of the press.” What Halberstam had called years earlier “the war within the war” continued until the last American troops left Vietnam.Footnote 72

Conclusion

That “war within the war” has had enduring legacies. Some commentators, such as Robert Elegant, who covered Vietnam for the Los Angeles Times, blamed hostile media coverage for turning US success on the battlefield in Vietnam into defeat by undermining popular support for the war effort.Footnote 73 So deeply embedded in popular memory is this belief in subversive reporting that an article in the Washington Post written fifty years after the Tet Offensive posed the question, “Did the News Media, Led by Walter Cronkite, Lose the War in Vietnam?”Footnote 74 Some military leaders indeed thought that Cronkite and his colleagues had snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. In subsequent conflicts in Grenada, Panama, Iraq, and Afghanistan, they limited access of reporters to troops and battle zones.

Yet the media coverage of Vietnam was hardly as skewed, slanted, or sensational as many critics allege. The American people experienced Vietnam as they had no previous conflict because television brought the war into their living rooms. Some of those film reports angered, outraged, and horrified individual viewers, but we can only speculate about the overall effects on the US public of TV news coverage or, for that matter, newspaper or magazine journalism. There is no detailed polling data that shows viewer or reader reaction to news reporting of Vietnam. In the absence of such systematic information, New Yorker critic Michael Arlen, who coined the term “living-room war,” suggested that television news programs may have “banalized” the war – making it seem “ordinary or remote” – by presenting a “stylized, generally distanced overview of a disjointed conflict” that usually failed to capture “any of the blood and gore, or even the pain of combat.” “It’s fascinating to me how misremembered Vietnam is,” Arlen recollected, “especially as far as the role that media played, that television played.”Footnote 75

If there is disagreement about the public reaction, there is no doubt that news reports from Vietnam unsettled high officials in the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations and led to persistent efforts to dismiss or disparage the stories in the newspapers or on the evening news. The reason that White House officials disliked what they read on front pages or saw on TV screens was not that the reporters in Vietnam were “too close to the story,” out to “get” the president, or determined to “stick the knife right in our groin.” Instead, what rankled presidents and their aides were stories about the hard realities, high costs, and inconvenient truths of a controversial war. The efforts of Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon to discredit the reporting of the television networks, prominent columnists, and correspondents for the nation’s leading newspapers established precedents, created arguments, and provided examples that a later generation of government officials used in 21st-century battles over “fake news.” Like so much of the US experience in Vietnam, the disputes over the reporting of the war remain part of the present, even as they recede further into the past.