Introduction

For the Fascist government, the preservation and consolidation of the ties between the diasporic communities and Italy were the cornerstones of its policies towards Italians overseas. Generally speaking, the task of ‘defending’ Italian identity was easier to undertake among that generation of Italians who migrated from the turn of the twentiethcentury rather than among their children (who we will call second-generation Italians for practical purposes). Among the former group, even if a sense of national identity was only forged through the Great War, factors such as the use of the native language, or more often the local dialect, a high level of inter-group marriage and sometimes the establishment of Little Italies, hindered the absorption of its members into the host society. Furthermore, even though the migrants had been forced to leave Italy due to its economic and social problems, feelings of nostalgia and links with relatives left in their native villages alsocontributed to maintaining a sense of Italian/local belonging. This conservation of heritage in the pre-Fascist era meant that when, during the ventennio, the regime attempted to preserve the allegiance of these first-generation Italians overseas – via activities carried out by Italian institutions, tours of Fascist emissaries, and the cult of Mussolini (Pretelli Reference Pretelli2015) – it found already fertile ground among many of them.

By contrast, second-generation Italians, usually individuals born either in a foreign country or, sometimes, to a non-Italian parent, were more liable to be assimilated into the indigenous population, for two reasons. Firstly, they acquired dual nationality. Thus, they were formally an integral part of the host country from their birth. Secondly, and of greater impact, integration happened through participation in education. In the schools, second-generation Italians, surrounded by their local fellow students, could start their process of absorption by learning the history and traditions of the host country, and especially the local language. The Fascist hierarchs in Rome, worried they might lose these young forces living overseas, planned a counter-process that aimed at ‘sowing’ in them the seeds of Italianità. This value comprised a myriad of moral and political concepts that saw their synthesis in national consciousness-building. In turn, de-nationalisation was meant to be avoided by this means. Therefore, the Fascist government, in order to instil, protect and enhance Italianità among the children of emigrants, created Fascist youth groups and developed a network of holiday camps in Italy. These initiatives were intended to compensate for the fact that these children had neither lived in nor even visited their parents’ country of origin, nor experienced the ‘spiritual palingenesis’ of war which, as previously stated, forged patriotism and national unity. The Italian schools overseas used to mould Italian identity and hinder assimilation into the country of birth were another crucial initiative. In this paper, the establishment and functioning of these schools by Italian Fascists in interwar Scotland will be investigated as a case study.

Drawing on extensive primary research – archival material from the Archivio Storico Diplomatico degli Affari Esteri (ASMAE) and Archivio Centrale dello Stato (ACS) in Rome, The National Archives (TNA) in London, and finally Italian and Scottish contemporary press – this article aims at contributing to the knowledge of Fascist efforts to nurture the allegiance of Italians abroad by focusing on schools. The article also investigates the wider topic of diasporic education in Britain under Fascism that only Claudia Baldoli (Reference Baldoli2003) has covered (although just for London schools in the 1930s). Other scholars who have focused on Italian communities in interwar Britain have either wholly neglected this topic (Chezzi Reference Chezzi2014; Hughes Reference Hughes1991; Marin Reference Marin1975) or analysed different contexts. For example, Sponza (Reference Sponza2000) has discussed the experience of Italians in Britain after Italy declared war on Britain in June 1940, while Colacicco (Reference Colacicco2018) has explored the Fascist effort to spread propaganda in British elite circles and universities by introducing Italian Studies there. Especially, Colpi (Reference Colpi1991), widely known for her expertise on the Italians in Scotland, and Ugolini (Reference Ugolini2011), who investigated the experience of Italians as an enemy alien group in Scotland after June 1940, have ignored the Italian schools in their studies. As will be seen, these represented an important tool not only as regards education and the penetration of Fascist propaganda, but also in terms of their social significance. Thanks to these schools, the community-building of Italian-Scots was generated. For this reason, another purpose of this paper is to include unpublished documents in the historiography of Italians’ social history in Scotland.

Before examining this channel of Italianità in depth it is helpful to give a general overview of the educational activities for Italian emigrants’ children in Scotland in the pre-Fascist period.

Italian schools pre-1922

At an institutional level, before Fascism's rise to power, the Italian school system overseas had begun to develop at the end of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, Italian schools were very few in number and underfunded. In January 1923, the writer Cesarina Lupati-Guelfi described the situation of the Italian educational system abroad, the ‘Great Cinderella’, as tragic: teaching staff were low-paid, and the fact that a few of these schools were still ‘alive’ was only thanks to ‘a terrific miracle’.Footnote 1 Thus, the primary responsibility of promoting Italian culture fell upon institutions such as the Catholic Church and the Dante Alighieri Society. The latter was set up in Rome at the end of the 1880s mainly as a cultural-political ‘weapon’ to redeem the terre irridente – Italian lands occupied by Austria (Baldoli Reference Baldoli2003, 8). In the years preceding the Fascist ventennio, this Society expanded globally. Its aim of disseminating the Italian language and heritage would also be pursued from the end of the 1920s and throughout the 1930s when the Society was fascistised (Cavarocchi Reference Cavarocchi2010, 169). In London, for instance, until the establishment of the local fascio, the schools were under the jurisdiction of St Peter's Church clergymen and the masons of the Society. This dualism led to bitter rivalries, especially after the Great War, when Camillo Pellizzi, founder of the London fascio and prominent Fascist intellectual, aimed at merging the schools under the aegis of the city fascio (Baldoli Reference Baldoli2003, 14).

When governmental or private institutions were missing from the diasporic community, private individuals took the initiative to promote education. They were either priests in their small congregations – a praxis spread especially among Italo-American communities – or proactive lay members of the community. The former scenario occurred, as mentioned, in London (St Peter's Church), and in Manchester, where the Manchester Italian Catholic Society was established. In Glasgow, where Britain's second biggest Italian immigrant community lived – in 1901, around 1,500 Italians resided there while about 4,000 were enumerated in the 1933 Italian census (Colpi Reference Colpi2015, 43,107) – the community failed to set up an ethnic parish (Colpi Reference Colpi1993, 159). Accordingly, prior to the advent of the Fascist clubs, in Scotland the second approach occurred: in February 1908, the booksellers Filippo and Gaetano Cafaro, founders of La Scozia, the first Italian newspaper published in Scotland (January–December 1908), conceived the idea of setting up a school for Italians. In the newspaper, they raised the issue of children's de-Italianisation caused by the lack of opportunity to speak Italian, and proposed that a school was needed to connect them to Italy.Footnote 2 As a result, in September 1908, the idea of a school for the diasporic community was presented to the Italian ambassador in London while he was visiting Glasgow. The ambassador warmly welcomed the proposal but clarified that the Italian government could not provide any economic support. He remarked, though, that it was the ‘patriotic duty of Italians in Scotland to find the means to teach their children the Italian language’ (Franchi Reference Franchi2012, 126). The school, however, remained a mirage. The lack of governmental help was not the only reason for this. Due to their socio-economic background, Italians showed very little interest in a school: the vast majority of them were shopkeepers and did not want to deprive themselves of their young and low-paid workforce, while many others, illiterate, did not see the need to educate their children. Later, the outbreak of the Great War contributed to that failure too.Footnote 3 Only from 1924 did Italian Fascists in Scotland resume further discussions on Italian schools and the Italian identity of emigrants’ children.

The creation and development of Italian schools in Scotland: the 1920s

In October 1922, Fascism came to power in Italy. After that, Fascist branches began to mushroom overseas. For instance, in Glasgow and Edinburgh, fasci were established in December 1922 and January 1923, respectively. This growing phenomenon led the Fascist government to set up in October 1923 the Segreteria Generale dei Fasci all'Estero. In its initial years, this agency struggled to co-ordinate the fasci overseas for two reasons. Firstly, Giuseppe Bastianini, its first secretary, saw in the new state body only a channel to pursue his ideological ambitions, that is, to create a ‘Fascist International’. Secondly, the bureaucrats of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs received with aloofness Fascism's rise to power (De Caprariis, Reference De Caprariis2000). When these difficulties were resolved between 1927 and 1928 with the fascistisation of the Ministry and Piero Parini's appointment as new secretary of the Fasci all'Estero, the network of fascist clubs, Italian schools, and youth organisations abroad was reinforced. However, the Italian Fascists in Scotland did not wait for Parini's secretariat to establish schools for their children.

In March 1924, an article entitled Nella Scozia italiana appeared in L'Eco d'Italia, the predecessor of the London Fascist weekly L'Italia Nostra, raising the same concern aired by La Scozia more than a decade before (L'Eco d'Italia 1924). The newspaper highlighted how the Italian schools in Scotland ‘are needed more than a thirsty person needs water’. It was recognised that new generations of Italian-Scots would have little language tuition from parents who ‘speak only their dialect’ and ‘are almost assimilated into the host country’. Furthermore, due to the dispersion and small size of Italian communities in some areas of the country, creating an Italian school in Scotland was a ‘huge problem’. People living in cities such as Dundee or Perth, or ‘spread in the countryside who were unable to travel up to two hours by car to attend an Italian class in Glasgow or Edinburgh’ were considered ‘lost to the Italian cause’. The allegiance of the second-generation Italians could not be retained through a school because ‘they are so few that its establishment would be impossible unless someone – who? [ironically asked the unnamed article's writer] – wants to waste money’. Only in Glasgow and Edinburgh could an Italian school be founded after overcoming some problems. In the former city, Italians were spread throughout the surrounding region. They had to resolve the issue of travelling distance which could hinder students' attendance. In Edinburgh, where Italians were spread out too, but the city was smaller, ‘a school could be established with great effort assuming that Italians can fight their old habit of apathy and indifference’. The last problem to arise was these communities' national sentiment which was ‘very weak as evidenced by the only Italian institution present in Scotland, that is the fascio’.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, the plea for an Italian education for children did not go unheeded this time.

One month later, in April 1924, Italian Fascist members in Glasgow opened the Ricreatorio domenicale – Sunday classes – for children of the community. This institution followed the visit to Scotland in February 1924 of Camillo Pellizzi who, in the meantime, had been appointed delegate of the fasci in Britain.Footnote 5 He probably lobbied for the creation of a school for Italian-Scots during one of his meetings with Italian Fascist leaders, considering that he was a keen believer in the centrality of Italian identity in emigrant communities – as demonstrated by the longed-for fusion of Italian schools in London – and in the fundamental role of education in instilling a strong identity. Officially, the Ricreatorio was not an Italian governmental school, but it laid its foundations. Two characteristics differentiated the Ricreatorio from a proper school. Firstly, it did not follow a formal school programme. Secondly, classes were held by members of the local female fascio – specifically constituted for this purpose – and not by professional teachers. This remained the case until 1937 when, as will be seen, the Fascist government sent a professional teacher. The decision to appoint women in charge of the Ricreatorio was perhaps groundbreaking in a hitherto highly patriarchal community where women were usually relegated to domestic roles. There were two likely reasons for this choice. One was the logical consequence of the nature of men's occupations. As shopkeepers, they were involved in their businesses, especially on Sunday, the week's busiest day. But women could guarantee a weekly commitment. The second reason was probably dictated by the need to attract more people around the fasci where, up to this point, no activities had been organised to encourage women's participation. Fascists seized the opportunity to remedy this by means of the schools.

The female fascio members Alice Norah Revel, Giulia Zani, Maria Pieraccini and Vincenza Migliorato initially held these Sunday classes for Italian-Scots in Glasgow. For three hours, they taught the first rudiments of the Italian language, patriotic anthems such as Giovinezza, and explained to the children that the king of Italy and Benito Mussolini ‘led their Fatherland's destinies’.Footnote 6 In the beginning, these lessons took place in the fascio headquarters which, after only four weeks, was accommodating 90 children divided into four classes. With this unexpectedly high number, Fascist leaders faced the problem of hosting the ‘little army’ in bigger and more comfortable spaces. Thus, from September 1924 until the establishment of the Casa d'Italia in May 1935, where the Italian school occupied an entire floor of the building, Fascist members relocated to a rented property in the city centre, at Renfield Place. In order to cope with the expenses of rent, books, stationery, and probably some reimbursements for instructors, Fascist members founded the Teatrino Sociale (from 1927 incorporated in the Dopolavoro section) that raised funds through social events such as plays, dances and concerts. For instance, in September 1924, at the opening of the Ricreatorio educational year 1924–5, the plays Una partita a scacchi and Il casino di campagna were performed in amateur productions.Footnote 7 In May 1926, the Glasgow Lord Provost Thomas Paxton and his wife, the Queen Margaret College director, and some city councillors, contributed money after attending the dance organised by Alice Revel to fund the Ricreatorio.Footnote 8 Again, in July 1931, an Italian by the name Autori and a Scot, Matthew Dickie, performed songs from the operas Carmen, Tosca, and Rigoletto.Footnote 9 In other years, lotteries and Carnival parties were organised for the same reason. These events became not only an opportunity to raise funds for the Italian school – they were also moments where Italian-Scots formed bonds within the diasporic and host community alike. Indeed, before this period, recreational activities were very rare.

The success of the Ricreatorio had considerable resonance within the diasporas in Britain. Soon after the establishment of the Glasgow Ricreatorio, Edinburgh Fascist members expressed their desire to imitate their compatriots. However, as will be discussed later, the Edinburgh Ricreatorio would only open in 1926 due to difficulties in finding a venue to host the high number of second-generation Italians. In London, L'Eco d'Italia wondered why, unlike Glasgow, the London community did not have such an institution that could assist the already existing Italian schools.Footnote 10 Thus, in May 1924, following this plea, the London fascio announced the setting up of a Ricreatorio, with its female group in charge of it.Footnote 11 The Italian Fascist pioneers of Glasgow perhaps felt additionally proud of and satisfied with their work when Mussolini, answering senator Scialoja's query in December 1924 on the fasci abroad, mentioned among other activities the Glasgow Ricreatorio.Footnote 12 Despite the wide reaction within Fascist circles, however, it can be argued that in 1924 the Italian community in Glasgow as a whole were aloof about enrolling their children. Even though every Italian child could access the Ricreatorio regardless of their parents’ Fascist membership, the vast majority of the 90 children who attended it were sons and daughters of the around 100 members of the local fascio.Footnote 13 This was a pattern that would continue to predominate, as will be seen.

Two years after its foundation, the Glasgow Ricreatorio became a proper school with an educational programme, and it grew in size. In 1926, the number of students more than doubled, to 208, and a kindergarten for children between four and six years old was created, as well as an evening school for adults who wanted to improve their Italian – many, as already noted, were illiterate or just spoke the local dialect.

For those who did not know the Italian language, teachers were focused on initiating the Italian-Scottish children (and adults) with subjects such as conversation, dictation, and reading. Children with solid language skills could improve them through grammar, composition, and a more challenging reading level. Perhaps Gaetano Cafaro lent or donated the first books to teach these subjects. In his bookshop, he had a large variety of suitable volumes, such as Grammatichetta and Grammatica grande, Dizionario Italiano, and Miniature parlanti (‘helpful to learn, read and write Italian’ as Cafaro noted).Footnote 15 It can be assumed that Cafaro, now a member of the Glasgow fascio, provided books because he could not miss the opportunity to see the development of the idea that he had strongly advocated in his newspaper in 1908. Moreover, the publication and distribution of government texts by Fascist Italy for students overseas began only at the end of the 1920s (Cavarocchi Reference Cavarocchi2010, 227). From Table 1, it can also be seen that although books from Italy were not distributed until later, the seeds of Fascist ideology were already being sown through other subjects. For example, in singing lessons, children were taught patriotic and Fascist anthems. At the same time, the three histories – Italian unification, Roman, and Modern – were meant to make the children aware and proud of their roots. Annual essay competitions instituted by Mussolini from 1925 had this purpose too. Children in Italy and abroad were asked to write short essays on different topics such as Roma; Il volo dell'ala tricolore sull'Oceano; and La Nuova Italia.Footnote 16 This limited exposure of Italian-Scottish children to Fascist propaganda between the 1920s and the early 1930s has been confirmed by some Italian-Scots. In Richard Wright's case study of the penetration of Italian Fascism into British-Italian communities (Glasgow, London and Manchester), the Italian-Scottish respondents from Glasgow who attended the Italian school between 1925 and 1932 said they had noticed very little propaganda (Wright Reference Wright2005, 125–34).

Table 1. School programme for Italian-Scots, 1925–6.Footnote 14

In 1926, while the Glasgow Ricreatorio became a school, the Edinburgh fascio officially opened its local Ricreatorio domenicale. Italian Fascists had been able to find headquarters in the central location of Picardy Place and economically supported the creation of Italian language classes despite the community – between six and eight hundred members – being hitherto divided on the subject. The Edinburgh Ricreatorio was inaugurated with great pomp. Two hundred Italians, a small delegation of Fascists from Glasgow, and Father Giacomo Salza, in Scotland for a Fascist propagandistic mission, gathered in the nearby St Mary's Cathedral. Salza and Ernesto Grillo – lecturer in Italian at the University of Glasgow – encouraged families to send Italian-Scottish children to the school to learn ‘Dante's language, the most beautiful language in the world’, and ‘the language of the Motherland which is the centre of Catholic civilisation’.Footnote 17 As in Glasgow, Fascist members in Edinburgh mainly relied on their own finances to boost their children's Italianità through the Ricreatorio even if there were fewer fundraising events. Money for the Ricreatorio and fascio activities was usually collected during anniversaries of the March on Rome, the days when the majority of the community was mobilised. In 1931, for instance, the lottery and dance organised to celebrate the March on Rome yielded £117.Footnote 18 In addition, the Italian school benefited from the close relationship between the local fascio and Scoto-Italian Society for a few years. Some Scottish people, members of this association, helped Italian teachers, watched Italian-Scottish students performing plays and poetry in Italian, and granted monies ‘for the fine educative work carried out by the fascio for Italian children’.Footnote 19

Unfortunately, the available sources on the Edinburgh Italian classes are not as detailed as those on the school in Glasgow. Even contemporary witnesses who lived in Edinburgh in the interwar period, when interviewed by Wendy Ugolini for her research on the experience of Italians during the Second World War, did not provide much information on the school aspect (Reference Ugolini2011, 68). However, it is probable that the same subjects as seen in Table 1 were taught to the second-generation Italians of Edinburgh. In 1926, the fasci members Assunta Elia, Orazio Di Domenico and Paolo Coppola would have taught basic subjects such as reading, conversation and dictation to introduce children to the Italian language. From the year after, 1927, when the Glasgow-born Vincenza Migliorato began to teach in Edinburgh too, it is possible that the school programme was standardised with that in Glasgow. As a result, in addition to learning the same subjects, those children in Edinburgh experienced the same Fascist propaganda. By contrast, as will be seen in the next section, those who attended the school in the 1930s, especially after 1935, were increasingly subjected to a fascio-centric education, with theme-based topics, propaganda films, and activities organised by the Fascist youth organisation.

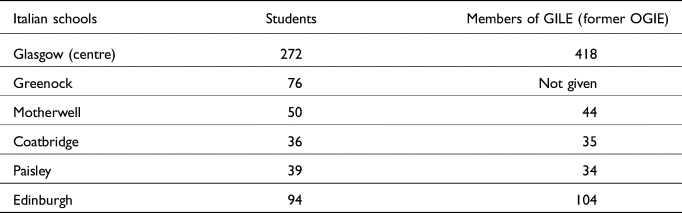

Table 2. Italian schools in Glasgow, West of Scotland and Edinburgh (1939). (Table 2, Guida Generale 1939, 436–45.)

As analysed so far, in Glasgow and Edinburgh the Ricreatori, created to defend and boost the Italian identity of new generations of Italian-Scots, thrived thanks to the Fascist commitment. In addition, through them some women had been mobilised and, to some extent, they functioned as a social glue between many diaspora members. However, the situation in other Scottish cities where local Fascist branches existed was not so fruitful. In Aberdeen, Dundee and Stirling, the fasci had been established relatively late – 1926 for the first two and 1927 for the latter – and Italian families living there were very few and scattered. As also anticipated by the L'Eco d'Italia article mentioned before, the dispersion of Italians in these locations meant economic and logistic difficulties in opening a school. In addition, the Fascist government did not provide any support and neglected the protection of the Italian identity of these small diasporic communities. These circumstances meant that during the 1920s schools were completely absent in those cities. Only from the beginning of the 1930s did local Fascist leaders in Aberdeen and Dundee take some initiatives to promote the Italian language among second-generation Italian-Scots.

The fascistisation of schools and Italian-Scottish children: the 1930s

The only initiatives taken by the local Fascist leaders in Aberdeen and Dundee to foster knowledge of the Italian language both occurred in 1933. In Aberdeen, the secretary of the fascio Emilio Bonici had to deal with ‘insurmountable problems’, namely, ‘the lack of a teacher, very few children – the oldest helped their parents in the shops – and their dispersion in the area’. Despite these factors, he was able to find a Catholic priest who ‘kindly gave lessons for a couple of hours on Sunday’.Footnote 20 In Dundee, Alessandro Paladini, member of the fascio committee, faced the same issues as indicated by Bonici in his correspondence with the Italian consul in Glasgow. However, he adopted a different strategy. Instead of looking for an instructor and opening a school, he founded a società filodrammatica.Footnote 21 In Paladini's view, children could learn and understand their native idiom by reading and performing amateur plays. The project was admirable but unfeasible. Despite the efforts made to overcome the ‘insurmountable problems’, both activities – the Italian language class in Aberdeen and the group of amateur actors and actresses – only lasted a few weeks (if not days). As for Aberdeen, Bonici happily pointed out that the priest, ‘who does not speak our beautiful language perfectly’, no longer had time to carry out this activity.Footnote 22 In Dundee, after the first play, Cosimo il Fabbro, performed in Lindsey Street Hall in front of an audience of 200 Italians, there is no evidence of similar shows, either in the contemporary press or in archival material. In addition, from the list of the performers, it can be deduced that the following among the community had been very small. The eight people involved in Cosimo il Fabbro came from only three families: the Paladinis, the Espositos, and the Cabrellis.Footnote 23

In the following years, the work of protecting the identity of Italians in these two cities was abandoned. Only in November 1938, after a visit to Aberdeen and Dundee, did the Italian consul in Glasgow, GianBattista Serra, urge the Fascist regime to send ‘a talented teacher who can lead these communities’. He noted that neither local fasci nor schools existed.Footnote 24 As a result, the Direzione Generale degli Italiani all'Estero (DGIE), which incorporated the Fasci all'Estero in 1929, attempted to ‘save’ the Italianità of its sons and daughters resident in these cities by sending Lieutenant Remo Bresciani from Italy. However, the attempt to reorganise the fasci and establish a school arrived too late.Footnote 25 The governmental negligence of the previous years, coupled with the obstacles mentioned before, perhaps eased that process of de-Italianisation that many, including some Fascists, experienced, from Aberdeen to Southampton, during the end of 1938 and the whole of 1939 (Baldoli Reference Baldoli2003, 149).

While in Aberdeen and Dundee the schools had been ill-fated, in Glasgow and Edinburgh they kept working. The ‘apathy and indifference’ of these communities in the pre-Fascist era had been tackled. The activism of the Glasgow fascio that the school contributed to triggering resulted in the purchase, in May 1935, of the Casa d'Italia, a luxurious three-storey building in Park Circus which soon became the centre of gravity of both adults and children in the Italian community. An entire floor with six rooms was devoted to lessons and group activities, indicating the special attention dedicated to them. Moreover, in the 1930s, in the Glasgow outskirts – Paisley, Coatbridge, Motherwell – other schools had been opened to reach those children who lived far from the city centre. These, at that time, became proper channels of Fascist ideology and propaganda. This process not only reflected the totalitarian aims of the regime but was also meant to have a greater impact on the development of children's national consciousness. The fascistisation of the schools started with the incorporation of the Direzione Generale delle scuole italiane all'estero into the ‘most fascist’ DGIE and the publication of government textbooks. The content of these books promoted values such as order, authority and discipline, and topics dear to the regime: the ‘Italian genius’ in the world; the battles won in the First World War by Italian soldiers; and Mussolini's life and speeches (Pretelli Reference Pretelli2010, 140–1). But the predominant aspect of the process of fascistisation was the entanglement between schools and the Organizzazione giovanile italiana all'estero (OGIE), the Fascist youth organisation for Italians abroad. The holiday camps in Italy were perhaps the best representation of this fusion. This is evidenced by one of Parini's circulars sent in 1933 to the Fascist clubs abroad, in which he reiterated that ‘the most assiduous and studious pupils of Italian schools and youth groups who act in the Italian way’ had to take preference to participate in the camps.Footnote 26 The learning of Italian, and the formation of feelings such as patriotism, nostalgia for Italy, and an awareness of the generosity of their motherland, were the prime aims of the camps, meant to reinforce the bond between young Italians and Fascist Italy (Baldoli Reference Baldoli2000, 168).

In Scotland, the fusion of the schools and the OGIE started in 1928, when the Fascist clubs reorganised the youth groups. Thus, in Glasgow, 196 OGIE members were taken from the 248 students enrolled in the Italian school.Footnote 27 They began to wear uniforms instead of jackets and ties (males) and white smocks (girls) during their weekly classes, and OGIE activities followed soon after the end of the lessons so that children were fully immersed in the Fascist doctrine for a whole day. Moreover, national identity and pride for the ‘New Italy’ were boosted from 1934 through propagandistic films. When this ‘weapon’ was used in Scotland, the maximum participation of students and members of OGIE was encouraged, as Italian consuls in Glasgow underlined in their reports.Footnote 28 It is also likely that, after these films, Italian-Scots were asked to discuss or write short essays, as were Italian students in London after the showing of ‘the greatest film of the Fascist era’, Camicia Nera.Footnote 29 This film, screened in Glasgow in 1934 for the March on Rome's annual celebration, was only the first of a long list of films that followed throughout the 1930s.Footnote 30 The prominent exposure to Fascist propaganda is also confirmed by looking at some poems delivered by Italian-Scottish students under the eloquent titles Son figlio della Lupa; Ti vedo o Duce; and Impero.Footnote 31 Richard Wright's interviewees give further evidence of Fascist promotional activities. Five out of the six Italian-Scots from Glasgow he interviewed recalled elements of Fascist education and activities in the classroom in the late 1930s (Wright Reference Wright2005, 130).

The role of the schools as the key channel to instil, protect and develop national consciousness in Italian-Scottish students reached its climax with the Abyssinian war. On the outbreak of war in October 1935, Piero Parini sent a circular to school directors and teachers abroad. He urged that the school had to become ‘a citadel of spiritual resistance. It must be one of the resistance fulcra where the students and their families can understand the rightness of Italy and the iniquity of others.’ In addition, before or after lessons, teachers had to read Parini's message for students in which, other than emphasising for propagandistic reasons his supposed pride in leading former students of Italian schools overseas in his legion of volunteers, he recommended:

To you, my little friends, falls a great and noble duty, that is, to be in these difficult hours for our Fatherland the true sentinels of the school. Sentinels of Italianità in a foreign country ensure that Italy's faith does not waver around you. The victory comes with justice and for this reason the Italian cause will have a wide and bright victory.Footnote 32

The duty of ‘Italian sentinels’ was displayed when Italian-Scottish students, maybe in spite of themselves, contributed to the Italian war effort. The teachers Vincenza Migliorato and Giovanni Cipolato, who perhaps wanted to demonstrate to the Fascist authorities the control they had over their pupils, or most likely because asked by the Italian consul in Glasgow, Ferruccio Luppis, collected medals and small items of value in their classes.Footnote 33 The prizes – mostly gold and silver medals – that Fascists had awarded to encourage educational and sports achievements were now going to Fascist Italy.

After the proclamation of the Empire in May 1936, the imperial-militaristic aspect of the regime was mirrored in the textbooks, which displayed a Balilla with a musket and the Empire's territorial borders. They also contained speeches by Mussolini, or celebrations of the victories in Ethiopia of Marshals Graziani and Badoglio (Baldoli Reference Baldoli2003, 149). These developments affected the diplomatic relationship with Britain. The word Italianità, which until that time was probably not known by most British officials, began to circulate in MI5 memoranda. One of these highlighted how ‘every effort is made [by Fascist Italy] to maintain Italianità and influence their [children's] minds at an early age’.Footnote 34 The authorities feared that British-Italian subjects, whose Italian identity had been nurtured in the schools and holiday camps, could in case of war, engage in sabotage against Britain. Accordingly, from 1936, the MI5 collected the names, and specified nationality, of children embarking from British ports to holiday camps in Italy. These lists would then be used on 10 June 1940, when the British government rounded up Italians and British-born Italians. One of these was the 16-year-old Edinburgh-born Edoardo Paolozzi, who later became a renowned sculptor, who was interned because his name appeared on one of the lists of 1937 when he embarked to take part in a summer camp in Italy.

Turning back to Scotland, the appointment of Giacomo Fermi, a professional teacher and officer of the militia from Genoa, as director of the Italian schools in Glasgow and the West of Scotland in October 1937 – in Edinburgh, the consular agent Mario Trudu was in charge of the local school – can be considered the last stage of the fascistisation process of the schools and students.Footnote 35 With this appointment, however, it is also likely that through Fermi, the Fascist government finally wanted to demonstrate support for Italian Fascists in Scotland. They had been able to keep the schools open with much effort for more than a decade without, according to sources, any allocation distributed from Italy. In 1939, their ongoing work led to the enrolment of almost 500 Italian-Scots.

By cross-checking the numbers in this table with fasci memberships, it can be argued once again that the family was the main route for the enrolment of these children in the schools. The large majority, if not the totality, of Italian-Scottish students came from families politically or socially involved in the fascio. In 1939, the fasci counted 586 members (470 men and 116 women) – including Motherwell, Coatbridge and Paisley – while 397 children attended the schools in the West of Scotland. In Edinburgh, in 1939 there were 188 Italian Fascists, and 94 students. These numbers also reinforce what emerged from Wright's oral interviews (Reference Wright2005, 104). More than two-thirds of his respondents from Glasgow, London and Manchester who attended the Italian schools had at least one parent involved in the respective fasci.

The meaning of the Italian schools in Scotland

The large majority of second-generation Italian-Scots were British-born. The Italian census carried out in Scotland by Fascist diplomats in the 1930s revealed that 2,579 out of 3,354 Italian children were born in Scotland (Colpi Reference Colpi2015, 56). In this context, it can easily be said that rather than protecting the Italian identity as Fascist hierarchs intended, the Italian schools had to ‘build’ the children's national consciousness from scratch. The political project behind the schools and youth groups was too arduous to achieve and for this reason proved unsuccessful despite the propaganda bombardment of the 1930s. When the Second World War confronted Italian-Scots with the choice of fighting either for Fascist Italy or Britain, almost all of them opted for the latter (Ugolini Reference Ugolini2013, 392). Among them, there were not only those Italian-Scots who had been wholly assimilated into Scottish society and were never enrolled in Italian schools, such as Alfredo Annovazzi and Attilio Lungo's sons,Footnote 36 but also those who did attend them. Ironically enough, some of them, like Giuseppe Franchitti, son of Gelsomino who funded the school in Motherwell, were sent to Italy as interpreters because of their language skills.Footnote 37 Fascists were perhaps satisfied to see that their language promotion had some effect. Finally, other Italian-Scots joined the British army even if not completely committed to the cause just in order to release their imprisoned fathers. It could also be argued, however, that many like them did not have the time to mobilise for Fascist Italy after the unexpected (by them) Italian declaration of war. Nevertheless, while Italy remained neutral in the first months of the war, Italian allegiance did not increase within the diasporic communities. During Italian neutrality, the Scottish press speculated that some Italian-Scots had given up British nationality only to avoid being conscripted by Britain.Footnote 38 Consular documents and British reports of that period neither confirm this speculation nor shed light on the phenomenon of Italian-Scots who wholeheartedly supported the Italian cause. The lack of archival material leads to the conclusion that, if the press accounts were accurate, only isolated cases of Italian allegiance among the second-generation Italians were occurring and it was highly likely that their choice was not driven by a true feeling of Italianità.

While the schools failed in their political role, the social contribution they gave to preserving language and developing community-building in Italian diasporas was much more significant. The objectives that many hierarchs such as Cornelio Di Marzio and Piero Parini reiterated in their Fascist rhetoric had been achieved to some extent. In one of his pamphlets, the former theorised that Fascism overseas had to ‘operate for Italianità, it has to stimulate a fervour of consensus and activities’ (Di Marzio Reference Di Marzio1923, 24). In Norme di vita fascista, a vade mecum for Italians abroad, Parini reminded them that ‘the language is the holy attribute of a population, the unique privilege of a race. To forget or reject it is a disgrace or a baseness’ (Segreteria Generale dei Fasci all'Estero Reference dei Fasci all'Estero1937, 27).

The schools did indeed curb the loss of the native language. Second-generation Italian-Scots attended Scottish schools daily and worked in their family-owned catering businesses which relied predominantly on indigenous customers. In addition, many of them, as seen before, came from families with poor Italian language skills. Therefore, language loss would have been inevitable and much more rapid in this scenario without the Italian schools. In addition, the schools (along with OGIE groups later) became the glue that bonded together many Italian-Scottish children. Before their establishment no Italian institutions existed where they could gather, perform activities and strengthen relationships. This can also explain why some families enrolled their children in schools and youth groups for reasons other than their Fascist membership. They perhaps considered these institutions helpful in mitigating racial marginalisation that their children sometimes experienced from Scottish teachers and classmates or locals more generally (Pieri Reference Pieri2005, 67; Ugolini Reference Ugolini2011, 36–7). The increase of OGIE membership in Scotland, as the British Home Office noted,Footnote 39 after the Abyssinian war exacerbated that anti-Italian sentiment, seems to reinforce this thesis.

In addition, the schools formed a social focus for adult members of the diaspora. Their foundation sparked the recruitment and mobilisation of many community members. Before 1924 and 1926, the main activities of the Glasgow and Edinburgh Fascist clubs were limited to the annual celebrations of the March on Rome and a few other Fascist ceremonies. As we have seen, women, until then relegated to domestic roles, were the first to be involved (later they would also be in charge of recreational activities such as Befana fascista), and the search for economic support for the schools led to an increase in the number of social events. Dances, dramas, and carnival parties revived a fair part of the Glasgow and Edinburgh communities which had been apathetic and individualistic in the pre-Fascist period. Unlike in Dundee and Aberdeen, the reasonable success of, and increasing participation in, these activities paved the way for the Dopolavoro sections that Fascists established later in 1926. These, in turn, contributed to the attractiveness of the Fascist clubs.

Conclusion

The Second World War had a significant impact on the Italian-Scottish community. In contrast to the pre-war period, mixed marriages between Italians and Scots, and the anglicisation of names, became more frequent. Many Italian-Scots wanted to be fully assimilated into society but, slowly, from the 1960s, others began to gather again in social clubs. In 1965, one of these, the Italian Comitato Culturale of Glasgow, established weekly classes for third- and fourth-generation Italians. The lessons were especially directed towards young Italian-Scots so that, according to the organisers, ‘the outcomes will be durable and not superficial’. They could learn Italian through games, poems and songs, taught by non-professional teachers in the community. These postwar era classes were arranged in the same way as the schools in the interwar period, but perhaps this repetition was unsuccessful in terms of participation. In available sources, data on those who joined these classes are not given, but it can be claimed that they did not attract a great following. In a survey of 1982–3, Sandra Chistolini asked a sample of 292 Italian-Scottish families (out of 5,000) whether children attended Italian classes. Forty-seven per cent of them answered no, and another 34 per cent refused to answer (Reference Chistolini1983, 135). This survey was not representative of the whole community but revealed the low level of interest in preserving the language. The aloofness of the community was reported during a two-day conference, Gli Italiani in Scozia: La loro lingua e la loro cultura, organised in 1985 by the Italian consulate. Here, scholars and other figures of the Italian-Scottish community gathered to share ideas and opinions for ‘the battle to support the Italian language and cultural pattern’, as the Italian consul in Edinburgh called it. They discussed solutions to reverse ‘the very low interest of the community [which] is often hidden’ as well as learning results that ‘are far from satisfying’. Ironically, Pietro Zorza, Italian chaplain in Glasgow and one of the speakers, perhaps unaware of the Fascist effort in Scotland during the interwar period, proposed activities such as the screening of films and lectures to disseminate Italian culture (Reference Zorza1985, 250). Possibly, they would not have worked. Very likely the scars that the Second World War had left on second-generation Italians were not healed yet. For this reason, they did not allow their children or grandchildren to join postwar Italian classes. The Fascist regime had wiped out the Italianità of various Italian-Scottish generations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Pietro Pinna, my friend Peter Williamson and the anonymous reviewer for their helpful suggestions.

Competing interests

the author declares none.

Remigio Petrocelli is a PhD student in History at the University of Dundee. His doctoral research focuses on Italian Fascism in Scotland.