Public and academic debates about gender and policy making during the COVID-19 crisis have been dominated, on the one hand, by a focus on women’s visibility or invisibility as decision makers in times of crisis (Piscopo Reference Piscopo2020; Smith Reference Smith2020). On the other hand, scholars have analyzed the gendered content and effects of COVID-19 responses and suggested ways to make these policies more gender-responsive (Cullen and Murphy Reference Cullen and Murphy2021; De Henau and Himmelweit Reference De Henau and Himmelweit2021). The inclusion of a gender perspective in COVID-19 policy responses is indeed vital to address the gendered effects of the crisis. This article takes a new perspective and uses the concepts and theories of feminist governance to discuss the effectiveness of the institutions and tools designed to promote gender equality during the COVID-19 crisis.

Feminist governance within political institutions can either play a role in ensuring the inclusion of a gender perspective in crises responses, or, quite the opposite, crises may weaken or sideline governance frameworks designed to support gender equality. In this article, we take feminist governance to signify the institutions and tools developed within political institutions to advance the inclusion of a gender perspective in policy making. Feminist governance provides institutional continuity and stability to gender equality policy making, yet it may be sidelined in times of political and economic crises.

The 2008 economic crisis that preceded the pandemic provides an example of a crisis context in which the inclusion of gender perspectives failed. Despite the well-documented gendered effects of the economic crisis and the ensuing austerity policies (Karamessini and Rubery Reference Karamessini and Rubery2013), it is now evident that inserting a gender perspective into the crisis response measures did not materialize in Europe (Cavaghan Reference Cavaghan, Kantola and Lombardo2017; Kantola and Lombardo Reference Kantola and Lombardo2017a). Economic policy, whose dominance over other policy fields was strengthened in the aftermath of the crisis, proved to be inaccessible for feminist knowledge and interventions (Cavaghan Reference Cavaghan, Kantola and Lombardo2017; Elomäki Reference Elomäki2021; O’Dwyer Reference O’Dwyer2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic provides an unprecedented example of a crisis that transforms and contests traditional policy-making processes and governance arrangements, including feminist ones. In this article, we address the functioning of feminist governance in the context of this crisis at the European Union (EU) level. Initially, gender perspectives were omitted from the EU’s response to the pandemic (Klatzer and Rinaldi Reference Klatzer and Rinaldi2020). This seems to suggest that at the very top of EU decision-making, its executive body, the European Commission, and the Council of the European Union, representing the member states, failed to make COVID-19 policies gender-equal. We nuance this interpretation by analyzing how the European Parliament engaged with the COVID-19 crisis and policies. The Parliament has the reputation of being the most gender-equal EU institution. Not only does it have a high representation of women (40% of parliamentarians), it has also been found to have a strong feminist governance framework (see Abels Reference Abels, Ahrens and Agustín2019; Ahrens Reference Ahrens, Ahrens and Agustín2019). At the same time, the Parliament is a site of political struggles and conflicts about the legitimacy of including a gender perspective in policy making. Feminist governance is a key site of political struggles.

The research objective of this article is to analyze the European Parliament’s response to COVID-19 from the perspective of feminist governance. The research questions are as follows: What role did the different institutions and tools of feminist governance play in gendering the COVID-19 crisis within the Parliament? To what extent did the European Parliament succeed in integrating a gender perspective into the EU crisis response, and what political struggles influenced the outcomes? Through the case of the European Parliament, we ask in more general terms, how have crises such as the global pandemic impacted feminist governance, and how effective or resilient is feminist governance within political institutions in crisis?

The empirical analysis of the article focuses on two key aspects of feminist governance: (1) dedicated gender equality bodies (as institutions) and (2) gender mainstreaming (as a policy tool). In relation to the first, the article looks at the actions of the European Parliament’s dedicated parliamentary body for gender equality, the Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM). More specifically, we analyze how the FEMM Committee constructed the pandemic as gendered in its report on gender perspectives to the COVID-19 crisis. In relation to gender mainstreaming, the article focuses on the European Parliament’s efforts to integrate the missing gender perspective into the EU’s historic COVID-19 recovery fund, called the Recovery and Resilience Facility. The research material consists of parliamentary documents such as draft reports, amendments, and final reports, as well as parliamentary debates. In addition to assessing the effectiveness of feminist governance, our analysis sheds light on the political struggles behind the policy positions by examining how important the gender perspective on COVID-19 was for the Parliament’s political parties (political groups) and the compromises that emerged between the ideologically different positions.

We argue that—unlike in the previous crisis—feminist governance in the European Parliament was successful in inserting a gender perspective into the COVID-19 response. The feminist governance institution—the FEMM Committee—succeeded in formulating a feminist analysis of the crisis and the EU’s policy response. However, its report might have remained isolated if other parts of the Parliament’s feminist governance framework had not played a role. The feminist governance tool—gender mainstreaming—succeeded in bringing a gender perspective to the EP’s position on the EU’s COVID-19 recovery fund, even if only in a watered-down manner. We contend that in the field of economic policy, even such “feminized” responses count as a success for feminist governance, as they would not appear otherwise.

The article is structured as follows: We first outline our theoretical approach, the concepts and theories of feminist governance. We then move on to the context of our analysis, the gendered character of the COVID-19 crisis and the gender-blindness of the EU’s initial crisis response, and describe our methodological approach and material. The analysis consists of three parts. We first look at how the pandemic affected the functioning of the Parliament’s feminist governance framework, and then we analyze the activities of the FEMM Committee, followed by gender mainstreaming. We conclude with findings on feminist governance in times of crisis.

Feminist Governance in Gendering the Covid-19 Crisis

Feminist governance is a broad concept used to discuss feminist institutions, organizing, advocacy networks, and policy-making tools at the national and transnational levels (Brush Reference Brush2003; Caglar, Prügl, and Zwingel Reference Caglar, Prügl, Zwingel, Caglar, Prügl and Zwingel2013; Shin Reference Shin, Disch and Hawkesworth2016). In this article, we use the term “feminist governance framework” in a specific sense to refer to institutions (e.g., gender equality bodies) and policy-making tools (e.g., gender mainstreaming, gender budgeting) within political institutions to promote policy making that takes gender into account. The effectiveness of feminist governance is shaped not only by the institutional conditions, but also by actors, such as politicians, activists, and staff, who work in these institutions and use these tools.

“Feminism” itself is a contested term, which can be filled with multiple meanings. Normatively, it calls for principles of governance that include attention to gender justice and inclusion. At a practical level, feminism implies an organizational structure that facilitates and enables the articulation and expression of distinctive points of view of marginalized groups, articulations of dissent, descriptive representation of all genders and marginalized groups and a reflection of this in leadership positions, and coalitions and networking with groups with shared goals (Kelly-Thompson, Tormos-Aponte, and Weldon, Reference Kelly-Thompson, Tormos-Aponte, Laurel Weldon, Sawer, Banaszak, True and Kantolaforthcoming). These are useful articulations of the ideals and principles for which feminist governance strives. Feminism points to a normative ideal, which often fails to materialize in practice.

Institutions and tools in the feminist governance framework have indeed been criticized for failing to live up to what feminism implies. First, even if institutions and tools are labeled as part of feminist governance, not all actors within them and using them are “feminist.” For example, parliamentary bodies, such as committees, include anti-feminist and anti-gender politicians and provide them with platforms to voice their opposition to gender and intersectional equalities. A related critique has been directed at gender mainstreaming, which is often implemented by civil servants who are tasked to do this in addition to their other work and have little awareness of gender questions (Verloo Reference Verloo2001). In relation to both, the term “critical actors” is useful to draw attention to the way in which actors matter for the success of these institutions and tools and to how some actors may be particularly influential for advancing gender equality within these structures (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009; see also Mushaben Reference Mushaben, Ahrens and Agustín2019).

Second, the concept of governance feminism captures the ways in which feminist principles and knowledge can be transformed—and become compromised—in interactions with national or international institutions’ priorities, which may be neoliberal, conservative, or populist (Griffin Reference Griffin2015; Halley Reference Halley, Hally, Kotiswaran, Rebouché and Shamir2018; Prügl Reference Prügl, Bustelo, Ferguson and Forest2016). The term “governance feminism” describes the co-optation of the policies, discourses, and dominant forms of knowledge of the broader political institutions that entrench existing economic and gender orders. For instance, gender mainstreaming in international institutions often legitimizes existing economic policies and goals that may be detrimental to the goal of gender equality (Elomäki Reference Elomäki2015; Prügl Reference Prügl2017). A focus on the implementation of technical governance tools, such as gender mainstreaming and gender budgeting, may sideline the goal of feminist transformation of gendered structures (Marx Reference Marx2019).

In response to these criticisms about the extent to which feminist governance is actually feminist, we contend that this criticism needs to be taken seriously and that there is a need to inquire whether, how, and under which conditions feminist governance succeeds or fails, and what form of feminism it promotes. In this spirit, Georgina Waylen (Reference Waylen2021) has argued for going beyond the co-optation narrative implied by governance feminism. In this article, we treat the feminism of feminist governance as an open empirical question that is important to scrutinize. We further justify the use of the concept of feminist governance by suggesting that it is a useful umbrella term that brings together related but distinct phenomena, such as dedicated parliamentary bodies or gender mainstreaming, that might otherwise be studied in isolation from one another. Analyzing the different aspects of feminist governance in conjunction with one another allows for comparative conclusions about their effectiveness, for example, in times of crisis.

These tensions around the relationship between feminist governance and feminism have been analyzed recently through the useful distinction between feminist and feminized responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (Cullen and Murphy Reference Cullen and Murphy2021). A feminized response to crisis “recognizes that a targeted policy response to women or a specific cohort of women is needed but falls short of seeking social transformation” (Cullen and Murphy Reference Cullen and Murphy2021, 351). In other words, it does not seek to transform gendered societal structures and may, in line with governance feminism, legitimize rather than challenge existing political priorities. Feminist responses, in contrast, go deeper. They are “characterized by resisting mainstream neoliberal discourse that seeks to individualize and frame problems in calculative rational terms.” Furthermore, feminist responses are likely to stress “connections across time, policy themes, and relationships that lead to a different form of response and to different alliance formations” (Cullen and Murphy Reference Cullen and Murphy2021, 351). The distinction usefully illustrates that feminist governance does not necessarily result in feminist policy outcomes.

In this article, we operationalize the concept of feminist governance through two aspects that are seen as crucial to its institutionalization and to the promotion of gender equality within political institutions: (1) dedicated bodies with a gender equality mandate and (2) gender mainstreaming strategies. In parliaments, gender-focused bodies include standing committees, single-party and cross-party caucuses, and issue-based parliamentary groups (Sawer Reference Sawer2020). Such bodies provide institutional legitimacy for advocacy in parliamentary settings, and, depending on their mandate, they may participate in the legislative process, keep the executive accountable for the implementation of gender equality policy, and provide an access point for feminist organizations. Gender mainstreaming, in turn, involves ensuring that gender perspectives and attention to the goal of gender equality are central to all parliamentary activities, from policy development and legislation to research, advocacy, and resource allocation (True and Mintrom Reference True and Mintrom2001). Gender-focused parliamentary bodies often play a key role in gender mainstreaming (Ahrens Reference Ahrens, Ahrens and Agustín2019; Sawer Reference Sawer2020). As in other institutions, in parliaments, too, the implementation of gender mainstreaming remains patchy, and it faces an additional challenge in the form of party-political struggles around gender equality (Elomäki and Ahrens Reference Elomäki and Ahrens2021).

Crises and the mechanisms to manage them often entrench the power of particular economic and gender orders and constrain the possibilities and space for contestation and critique (Griffin Reference Griffin2015). They also make feminist governance particularly vulnerable. Extant research shows that gender-focused bodies and gender mainstreaming have been sidelined at times of economic crisis (Cavaghan Reference Cavaghan, Kantola and Lombardo2017; Guerrina Reference Guerrina, Kantola and Lombardo2017), and gender perspectives have only been accepted in instrumental and diluted forms that dismiss feminist critique of dominant economic ideas and policies (Elomäki Reference Elomäki2015, Reference Elomäki2021).

Feminist governance thus takes different forms, such as parliamentary bodies and gender mainstreaming, and exhibits various levels of and approaches to feminism. Economic, social, and political crises have in the past sidelined feminist governance in political institutions, even if such crises constitute times when inserting a gender perspective into policy making would be particularly pertinent. The European Parliament constitutes an excellent example for analyzing these questions of feminist governance, having adopted its institutions, policies, and actors with varying degrees of success.

COVID-19 as a Gendered Crisis and the EU’s Gender-Blind Crisis Response

Economic and other crises are often gendered in their effects, key actors, policy responses, and narratives, and they may be detrimental to different marginalized groups (Emejulu and Bassel Reference Emejulu, Bassel, Kantola and Lombardo2017; Hozic and True Reference Hozic and True2016; Kantola and Lombardo Reference Kantola and Lombardo2017a). This has also been the case with the multiple crises caused by COVID-19. The gender and intersectional impacts of COVID-19 and measures to contain the pandemic have been manifold. Women, who make up the majority of the health care workforce, have been leading the health response, exposing themselves—and their families—to a higher risk of infection. The impact of the pandemic has fallen disproportionately on black and ethnic minorities and calls for analysis of socioeconomic factors as well as discrimination in national health care systems (Garcia et al. Reference Garcia, Homan, García and Brown2021). Rates of domestic violence have increased under lockdowns, to the extent that violence against women has been termed a “shadow pandemic,” and services have been harder to access under lockdowns (e.g., Mahese Reference Mahase2020). The pandemic has also increased gender inequalities in both paid and unpaid work, at least in the short term. In many countries, the first phase of layoffs hit the female-dominated private services sector hard (e.g., Alon et al. Reference Alon, Doepke, Olmstead-Rumsey and Tertilt2020; Farrè, González, and Graves Reference Farré, González and Graves2020). At the same time, women have been shouldering much of the additional burden at home as a result of school and child care facility closures (Craig and Churchill Reference Craig and Churchill2021; Johnston, Mohammed, and van der Linden Reference Johnston, Mohammed and van der Linden2020). As a consequence, in many countries, women have had to reduce their hours of paid work or even drop out of the labor market completely (Collins, Landivar, and Scarborough Reference Collins, Landivar and Scarborough2020).

In addition to magnifying inequalities, the COVID-19 pandemic has further intensified the crisis of care and social reproduction connected to the neoliberal austerity and marketization policies of past decades. At the same time, it has demonstrated the foundational role of care—both paid and unpaid—to the functioning of societies and economies and keeping societies afloat in a crisis situation (Bahn, Cohen, and Rodgers Reference Bahn, Cohen and van der Meulen Rodgers2020; De Henau and Himmelweit Reference De Henau and Himmelweit2021; Heintz, Staab, and Turquet Reference Heintz, Staab and Turquet2021). Yet care and the way it enables the functioning of the “productive economy” is ignored or undervalued in economic decision-making (Heintz, Staab, and Turquet Reference Heintz, Staab and Turquet2021) and crisis management (Branicki Reference Branicki2020). The concept of care has become a key part of visions for a feminist and socially transformative response to COVID-19. While some scholars have called for crisis management based on feminist ethics of care (Branicki Reference Branicki2020), others have rallied around the concept of a care economy, which draws on feminist economics and political economy research (Bahn, Cohen, and Rodgers Reference Bahn, Cohen and van der Meulen Rodgers2020; De Henau and Himmelweit Reference De Henau and Himmelweit2021). Calls for a care economy typically entail making human and environmental well-being rather than economic growth the center of policy, recognition of care as an integral part of the economic system, and investments in care and social infrastructure.

The EU’s response to the 2008 economic crisis and the ensuing Eurozone crisis centered on the imposition of austerity policies on crisis countries and economic governance reforms that made austerity a permanent state of affairs in member states. This led to significant gendered impacts and weakened care infrastructures (Bruff and Wöhl Reference Bruff, Wöhl, Hozic and True2016; Kantola and Lombardo Reference Kantola and Lombardo2017a). The response to the COVID-19 crisis, in contrast, focused on making funding available for the member states to tackle the economic and social impacts of the crisis. The main part of the EU’s response is a €750 billion (more than five times the EU’s annual budget) recovery package called Next Generation EU. Most of the money (€672.5 billion) is distributed to the member states as grants and loans through the recovery fund, called the Recovery and Resilience Facility. The recovery package signifies a temporary end to the EU’s austerity policies, but not to the EU’s equally gendered and neoliberal reform agenda, which focuses on making individuals fit for the market, increasing the labor supply, and making public services more effective (cf. Copeland Reference Copeland2020). The grants and loans are conditional on reforms and investments that conform to the EU’s neoliberal agenda (Klatzer and Rinaldi Reference Klatzer and Rinaldi2020).

The EU’s austerity-focused response to the previous economic crisis was silent about gender and care (Elomäki Reference Elomäki2021; O’Dwyer Reference O’Dwyer2018), and this was also the case with the COVID-19 measures. The European Commission’s proposal for Next Generation EU focused on transformation toward a green and digital economy and only mentioned gender equality in passing (EC 2020a). The well-documented gender impacts of the COVID-19 crisis were mostly sidelined, and neither the recovery of the care sector nor a transition toward a care economy was included in the proposals. The European Commission set no gender-related objectives or gender mainstreaming requirements for the recovery fund (EC 2020b). During the Eurozone crisis, the silence about gender and care served to legitimize austerity (Elomäki Reference Elomäki2021; O’Dwyer Reference O’Dwyer2018); this time, it led to policies that did not advance everyone’s recovery and well-being. According to one assessment of the proposal, a large share of economic stimulus would be allocated to sectors with high percentages of male employment, such as energy, agriculture, construction, and transport, even if female-dominated sectors were most affected by COVID-19 (Klatzer and Rinaldi Reference Klatzer and Rinaldi2020).

The sidelining of gender perspectives in the European Commission’s proposal came at a time when there were high expectations for advancing gender equality connected to Ursula von der Leyen, its first-ever female president. Von der Leyen, who took office in 2019, had made gender equality a key component of her program (Abels and Mushaben Reference Abels and Mushaben2020). Not only did this program indicate an end to the long trajectory of sidelining gender equality at the EU level, which the previous economic crisis had intensified (Jacquot Reference Jacquot, Kantola and Lombardo2017), it also created new feminist governance institutions within the European Commission and strengthened gender mainstreaming (Abels and Mushaben Reference Abels and Mushaben2020). However, at the Commission level, the gender equality impacts of COVID-19 were pushed aside despite the enhanced feminist governance framework. This illustrates the persistence of political-institutional obstacles, such as weak gender mainstreaming structures, but also the specific challenges that crises pose for feminist governance.

In contrast to the European Commission, the European Parliament has historically taken the role of inserting a gender perspective into EU policies through the efforts of outspoken feminist politicians and its feminist governance framework, which includes the FEMM Committee and a commitment to gender mainstreaming (Ahrens Reference Ahrens2016, Reference Ahrens, Ahrens and Agustín2019). Extant research has shown that the FEMM Committee pushed the Parliament to take this role in relation to the 2008 economic crisis, too, but its efforts did not have an impact on the EU’s austerity politics (Guerrina Reference Guerrina, Kantola and Lombardo2017; Kantola and Lombardo Reference Kantola and Lombardo2017a). Given the European Commission’s initial silence about gender and care in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Parliament was again left with the task of inserting the omitted gender perspective.

Methodological Approach and Research Material

The theoretical and methodological approach adopted in this article is constructivist and discursive. For the empirical analysis, this signifies studying how the meanings of “feminism” and “gender equality” are constructed in political processes (Kantola and Lombardo Reference Kantola and Lombardo2017b; Lombardo, Meier, and Verloo Reference Lombardo, Meier and Verloo2009). In other words, they do not have fixed meanings, but rather take on different normative meanings in disputes that political actors engage in (Bacchi Reference Bacchi2009). The “gender equality” advanced by feminist governance, then, is always an outcome of political struggles over its meaning. The constructivist and discursive approach analyzes all policy problems as constructed in many ways, thereby offering an array of policy solutions to policy problems and closing off other alternatives (Bacchi Reference Bacchi2009).

The discursive approach calls for an analysis of the political struggles that surround gender equality. In the context of the European Parliament, these struggles take place between and within the so-called political groups, the large conglomerates of member states’ national political parties. Earlier research has shown that political groups’ gender politics and constructions of gender equality differ. The lines of consent and consensus are issue-specific, but economic policy is a field in which gender equality is particularly contested (Elomäki Reference Elomäki2021; Kantola and Rolandsen Agustín Reference Kantola and Agustín2016, Reference Kantola and Agustín2019). The Parliament’s radical right groups have explicitly articulated a discourse that the EU should not intervene in the area of gender equality, challenging the notion “gender” and speaking rather of “men and women” (Kantola and Lombardo Reference Kantola and Lombardo2021; Kuhar and Paternotte Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2017). During the period studied in this article, the Parliament’s seven political groups, in order of size, included the Group of the European People’s Party (Christian Democrat) (EPP), the Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament (S&D), the liberal Renew Europe Group, the radical right populist Identity and Democracy Group (ID), the Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA), the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR), and the Left Group in the European Parliament (GUE/NGL).

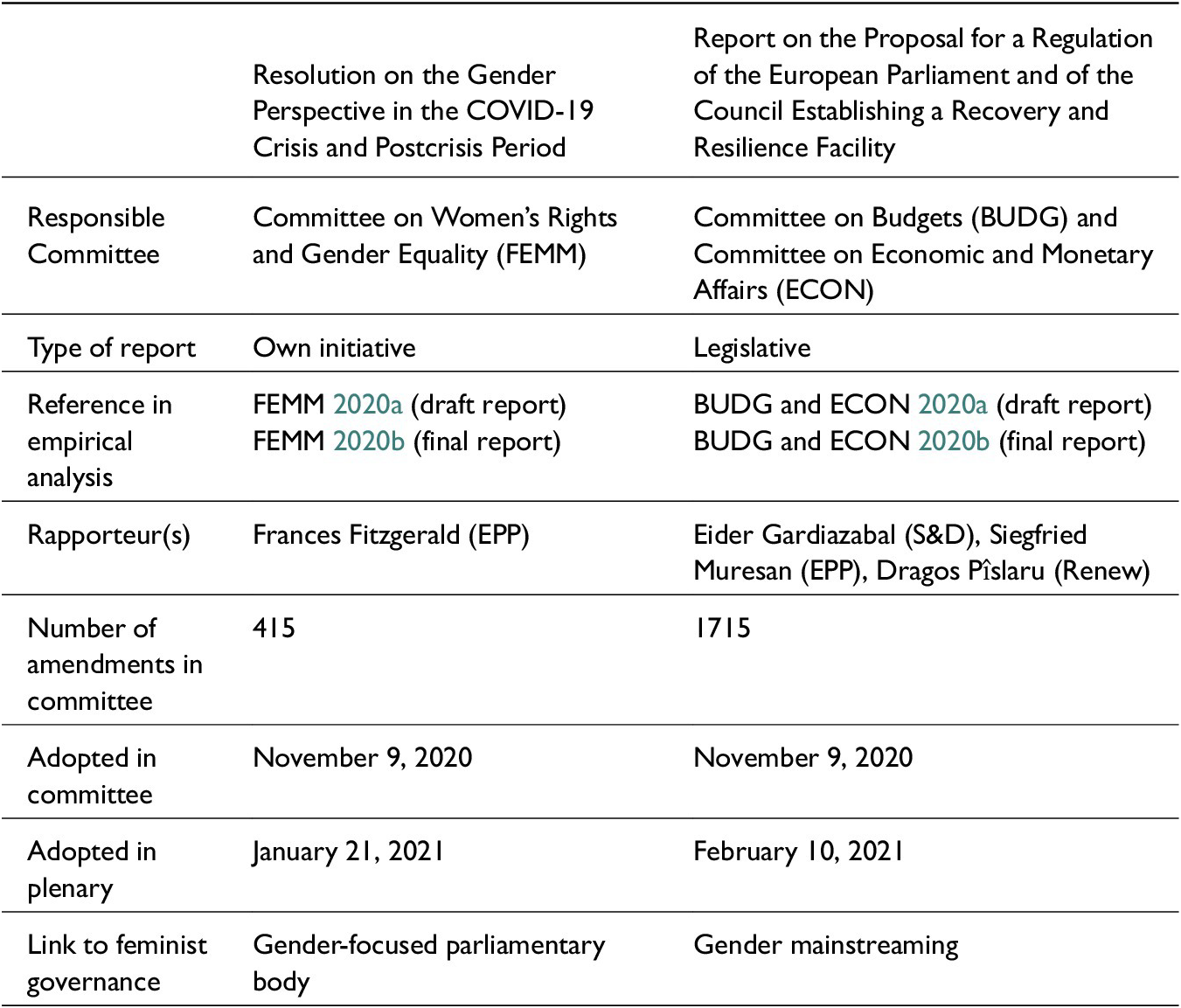

The empirical analysis focuses on the key actions of the European Parliament’s dedicated gender equality body, the Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM), in response to the COVID-19 crisis. These actions centered around drafting and debating a report on gender perspectives on the COVID-19 crisis (see Table 1). We analyze how the FEMM Committee functioned as a gender-focused parliamentary body and tried to raise awareness of the gender impacts of the crisis. We then analyze the functioning of gender mainstreaming in the crisis context in relation to the EU’s key economic recovery instrument, the €672.5 billion Recovery and Resilience Facility. We assess by whom and with what outcomes gender perspectives were integrated into the Parliament’s position on the facility (Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of the research material

The research material consisted, first, of the two draft reports written by the Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) in charge of the file. Second, the research material included more than 2,000 amendments made by MEPs from different political groups that suggested changes to the draft (or, in the case of the recovery fund, to the European Commission’s proposal). Third, the research material contained the texts adopted by the Parliament following negotiations and compromises between the political groups and, finally, the parliamentary debates related to the reports.

In line with our approach, we analyzed the extensive material with a focus on constructions of gender in relation to the COVID-19 crisis, assessing the extent to which these constructions were feminized or feminist (Cullen and Murphy Reference Cullen and Murphy2021). We identified competing constructions and political struggles by analyzing the changes that MEPs with different political backgrounds proposed to the draft report and comparing these amendments with those of other political groups. Plenary debates were used to further understand the differences. Finally, in order to determine which constructions were included in the compromises between the political groups and the adopted positions and which were marginalized, we compared draft reports, amendments, and the adopted texts. The analysis process required close reading of the material, theoretically informed analysis of the different constructions of gender equality, and nuanced knowledge about the seven political groups and the political backgrounds of the MEPs, as well as the Parliament’s decision-making processes.

The European Parliament’s Feminist Governance Framework During the Pandemic

To begin our analysis, we assess how the pandemic affected the feminist governance framework within the European Parliament, notably, the FEMM Committee and gender mainstreaming. Although the feminist governance framework within the Parliament is seen as relatively strong and institutionalized, scholars have raised concerns about its effectiveness. The COVID-19 pandemic considerably affected parliamentary work, posing further challenges.

The FEMM Committee is the European Parliament’s dedicated parliamentary body for gender equality. It conducts extensive debates on gender equality issues and strives to integrate gender perspectives into the Parliament’s work and EU policies across policy fields. Although scholars regard the FEMM Committee as important for the EU’s gender equality policy, within the Parliament, it has less prestige than other committees. For example, it has rarely been in charge of the Parliament’s position on EU legislation (Ahrens Reference Ahrens2016). Although the FEMM Committee is able to reach consensus on more far-reaching policies on gender equality than the Parliament as a whole, political conflicts often emerge within the committee, too, not least given the presence of the radical right groups (Kantola and Rolandsen Agustín Reference Kantola and Agustín2016, Reference Kantola and Agustín2019).

The FEMM Committee’s weak institutional position became visible when the Parliament adapted its working practices in response the COVID-19 emergency. FEMM was one of seven committees whose work was completely suspended in spring 2020, and even in the summer of that year, it met less frequently than most other committees.Footnote 1 As a result, during a critical time when the gendered impacts of COVID-19 were unfolding and the Parliament began to formulate its stance on the EU’s recovery measures, the FEMM Committee hardly met. The suspension measures thereby temporarily prevented the deliberations of the Parliament’s key feminist governance institution at the very moment of a crisis with immense implications for gender equality. Despite the suspension, key members of the committee continued to work together and eventually initiated a COVID-19 report, which is discussed in more detail in the next section.

With regard to gender mainstreaming, the European Parliament is one of the rare parliaments that has committed to implementing this feminist governance tool (Ahrens Reference Ahrens, Ahrens and Agustín2019). Gender mainstreaming in the Parliament functions through two channels. First, the FEMM Committee can give opinions or make so-called gender mainstreaming amendments for other committees. These opinions and amendments are adopted in FEMM and sent to the lead committee, which can (but is not required to) adopt them (Ahrens Reference Ahrens, Ahrens and Agustín2019, 97). Other committees often disregard FEMM’s input (Ahrens Reference Ahrens2016; European Parliament 2018), as was the case with the previous economic crisis and its gendered impacts (Guerrina Reference Guerrina, Kantola and Lombardo2017). Second, each committee should take measures to integrate a gender perspective in its own policies, but here, too, implementation has been slow (Ahrens Reference Ahrens, Ahrens and Agustín2019). Finally, individual parliamentarians supportive of gender equality, many of whom are FEMM members, push for the integration of gender perspectives in different committees. In the Parliament, as at the EU level more broadly, integrating a gender perspective into economic policy has been particularly difficult. Gender-related amendments, whether by the FEMM Committee, individual parliamentarians, or political groups, rarely make it to the adopted reports, and they are mainly welcomed when they support dominant goals and policies (Elomäki Reference Elomäki2021). Gender mainstreaming is an object of party-political struggles, too: some political groups are more likely to push for the integration of gender perspectives, whereas others ignore or systematically work against gender mainstreaming (Elomäki and Ahrens Reference Elomäki and Ahrens2021). Despite a certain level of institutionalization, the challenges for gender mainstreaming as a feminist governance tool remain considerable.

In the early phase of the pandemic, the Parliament mainly worked under the “urgent procedure,” which meant that legislation passed through as quickly as possible, without the involvement of the committees, which are the locus of the Parliament’s legislative work and political debate (von Ondarza Reference von Ondarza2020). This arrangement, which allowed the Parliament to work efficiently during the pandemic, significantly limited the Parliament’s ability to influence policy outcomes and curtailed democratic deliberation. The urgent procedure and other restrictions on parliamentary work also limited the Parliament’s ability to integrate the omitted gender perspectives into the response policies in the early phase of the pandemic. However, by the time legislative work on the recovery fund began in the autumn of 2020, the Parliament had returned to normal procedures, even if in a hybrid format. Although many key decisions about the recovery fund, including its size, had already been made by the heads of EU member states, the Parliament was in the position to influence the general funding priorities and implementation rules—as well as to integrate the missing gender perspective.

The FEMM Committee: Putting Gender Back on the Agenda During a Crisis

In this second part of the analysis, we focus on the FEMM Committee as an example of a feminist governance institution and analyze what it did to insert a gender perspective into the COVID-19 pandemic response and the political struggles that were involved. This enables a response to our research question asking whether feminist governance in the form of an institution can succeed in integrating a gender perspective into the bigger institution’s crisis response, and to discern what kind of gender perspective that is.

Drafting nonlegislative reports is one of the FEMM Committee’s main strategies to raise gender issues on the agendas of the Parliament and the EU, and it used this strategy during the COVID-19 crisis, too. The FEMM coordinators of the political groups (i.e., the people whom the political groups nominated to be in charge of their work in that committee) decided to initiate a report on gender and the COVID-19 crisis in April 2020, and responsibility for it was given to the biggest group, the center-right EPP. The rationale was to draft a collaborative report and have it adopted with broad political consensus in order to project a strong, united voice across all EU institutions. The FEMM Committee was concerned about the lack of a gender perspective in debates on the pandemic, as shown in the following citation by the parliamentarian in charge of the report:

I am concerned, I don’t see a huge amount of evidence of gender being taken into account in the recovery funds and discussion and talk to date across the leadership. I do want to say that. I think the gender is missing a lot. It is like before, it is always an add-on, and we got to ensure it is integral. And we have to use the influence of the FEMM Committee across the board to make sure this happens. And I am concerned about it, I don’t see much evidence of its presence. . . . It is very serious. There is a huge amount of money and if there is no focus on gender, women will simply lose that. (Frances Fitzgerald, EPP, FEMM meeting, June 25, 2020)

However, reflecting the disregard of the committee within the Parliament, the leadership of the Parliament postponed the authorization of the report, which significantly delayed its adoption. Although the report was drafted already in June 2020, it took until the end of August for the adoption process to begin. The delay meant that the committee could not use the insights of the report in its interinstitutional discussions about the recovery fund, as it had intended. In the adoption process, FEMM Committee members submitted more than 400 amendments, proposing changes to the content of the draft report. The committee adopted the report by a broad coalition of center-right, center-left, and left groups. Radical right populists voted against or abstained. The report was adopted by the Parliament in January 2021.

The draft report shows that the FEMM Committee discussed gender equality in relation to the pandemic in an expansive way. The draft report covered gender-specific issues, such as sexual and reproductive health and rights and violence, and addressed general COVID-19-related issues, such as the economy and recovery, from a gender perspective (FEMM 2020a). Despite being drafted by a conservative politician, the report did not shy away from sensitive topics, such as sexual and reproductive health and rights and the Istanbul Convention on violence against women and domestic violence, which have proved to be politically divisive in the European Parliament. For instance, the Istanbul Convention, which European anti-gender activists have attacked as “gender ideology,” has been opposed by the parliament’s radical right populists and other anti-gender members (Berthet, Reference Berthetforthcoming). In other words, the draft report represented, at many levels, a feminist rather than a feminized response to the crisis (cf. Cullen and Murphy Reference Cullen and Murphy2021). Yet the amendments demonstrate the political struggles beneath the FEMM Committee’s collaborative rhetoric. These struggles were connected, on the one hand, to constructions of the crisis as gendered and to gendering the recovery policies, on the other.

With regard to gendering the crisis, the first conflicts emerged around the very concept gender, illustrating how the use of the notion of “gender,” as opposed to “women and men,” has become a contested in Europe. The left, green, and liberal groups used the notion of “gender” as a socially constructed category of masculinities and femininities. They also used the concepts of LGBTQI rights and intersectionality and aimed at mainstreaming intersectionality across the report. This is in line with feminist theories emphasizing intersectionality and gender as categories that reveals unequal and structural power relations, and thereby resembles a feminist approach to the crisis. The biggest group in the Parliament, the EPP, did not directly oppose such definitions of gender equality. However, in its own amendments, the group sometimes preferred the weaker language of “gender sensitiveness” (Amendment 147), which can be interpreted as sensitivity to the (“natural”) differences between women and men rather than questioning or destabilizing these differences.

The amendments also revealed direct opposition to gender equality from within the feminist governance institution. The radical right populists from the ECR and ID groups used the FEMM report to voice their opposition to the use of the words “gender” and “LGBTQI rights.” They tabled amendments to delete words and paragraphs that contained references to gender, trying to block any understandings of the gendered structures shaping people’s experiences of the pandemic and the policy responses that might mitigate the impact on the most vulnerable groups. An ECR parliamentarian even called intersectionality an “ideological theory” (Amendment 344). In the radical right populists’ attempts to advance gender equality as a harmful “gender ideology” (Kuhar and Paternotte Reference Kuhar and Paternotte2017), they stressed the importance of the heterosexual nuclear family. In this debate, too, they constructed the family as the safest environment against the crisis and stressed the importance of marriage, sidelining the heightened levels of gender-based violence at home during the pandemic.

In this polarized atmosphere against gender equality, the left, green, and liberal groups constructed gender equality during the pandemic to include sexual and reproductive health and rights and gender-based violence. On violence, they put forward amendments to specify it as gender-based and to recognize the detrimental impact of lockdown measures and the inadequacy of public services across member states (e.g., Amendments 209–212, 218–220). The EPP’s construction of the issue was slightly more feminized, as these conservative parliamentarians preferred the language of domestic violence and women rather than gender (Amendment 213). Also, formulations on the unequal division of care, lack of care services, and weak position of carers divided the political groups.

Ways of gendering the EU’s recovery policies—a key intention behind the FEMM report—further illustrate different understandings of gender equality and the political means to achieve it within this feminist governance institution. The social democrats and the greens tabled amendments with explicit references to learning from the mistakes that led to the sidelining of gender during the 2008 economic crisis (Amendments 140, 144). The left groups, greens, and liberals strongly supported the inclusion of gender mainstreaming, gender budgeting, and gender impact assessments in the EU’s recovery instruments, and they called for funding for specific gender equality measures (e.g., Amendments 317–321). In this way, they challenged the gender-blindness of the proposed EU crisis response.

Building on the ideas and concepts of feminist economists (e.g., De Henau and Himmelweit Reference De Henau and Himmelweit2021), the left and green groups called for a comprehensive “care deal” as part of the EU’s recovery policy (Amendments 271, 317–321). They argued that such a care deal aimed at supporting a transition toward a care economy, which would require investment and legislation at the EU level and take both formal and informal care into account in policy making (Amendments 271, 273). The conservative EPP, in contrast, merely suggested the expansion of different forms of care and support for caregivers (Amendment 272). Indeed, the EPP’s approach resembled a feminized response, recognizing the need for a targeted support for women but not seeking social and economic transformation.

The outcome of these struggles was that gender and intersectional perspectives were strengthened in the final report, and the radical right opposition to them was not effective in the committee (FEMM 2020b). The economic recovery instruments were discussed in more detail in the final report than in the draft report, and the tools of gender mainstreaming, gender budgeting, and gender impact assessments were put forward as important for gendering the crisis response. However, the care deal was not mentioned, although investment in care was emphasized (FEMM 2020b, 11).

Our analysis of the FEMM Committee as an example of a feminist governance institution that seeks to insert a gender perspective into the EU’s crisis response has shown its success—after initial procedural challenges within the Parliament—in producing a feminist response to the COVID-19 pandemic. While the EU’s approach to the crisis was initially driven by economic policy, the FEMM Committee constructed the gendered and intersectional effects of the crisis as covering a broad range of fields. The political groups put different emphases on intersectionality, care, and the economy, but they were able to reach a progressive consensus to lobby for the inclusion of a gender perspective in EU policy. The FEMM report can be interpreted as setting an agenda for the gender analysis of the crisis and for the integration of a gender perspective into policy responses. Yet, the actual success and impact of these ideas were tested elsewhere, an issue we turn to next.

Gender Mainstreaming the EU’s Recovery Fund: Coordinated Efforts of the Technical Approach to Gender Equality

The decision to establish the €672.5 billion recovery fund was the most important COVID-19 response policy adopted by the European Parliament. Therefore, we analyze gender mainstreaming as a key feminist governance tool in relation this fund. In line with our research questions, we ask how gender mainstreaming functioned in the Parliament during the crisis, what political struggles emerged over its use, and to what extent the Parliament succeeded in integrating a gender perspective into the fund.

The Parliament’s position on the European Commission’s proposal for the recovery fund was drafted jointly by its key economic actors, the Committee on Budgets (BUDG) and the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON). Given the salience of the issue and the importance of reaching a political compromise, the three biggest political groups (EPP, S&D, Renew) shared responsibility for the report, each nominating one rapporteur (see Table 1). The position was a topic of heated political debate that focused on the use of the recovery money. Nine committees, including the FEMM Committee, gave opinions to the committees in charge, and the members of the economic and budgetary committees proposed more than 1,700 amendments. The committees adopted the report with a broad majority consisting of the three main groups and the greens. The Parliament’s key requirements were related to extending and specifying the scope of funding, earmarking a larger share of the funding for climate and biodiversity, and giving the Parliament a role in its monitoring. A political agreement between the EU institutions was reached in December 2020, and the Parliament approved the agreement in February 2021.

With regard to the functioning of gender mainstreaming, our analysis of the recovery fund suggests the resilience of this feminist governance tool in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Gender mainstreaming worked despite the potentially hostile environment of a difficult policy field (economic and budgetary policy) and committees with a poor track record of taking gender equality into account (cf. Elomäki Reference Elomäki2021; European Parliament 2018). Surprisingly, the draft report contained references to gender equality, suggesting that gender mainstreaming was important for at least some of the three political groups in charge of the report. For example, the three rapporteurs required that recovery money should be used to “fight against poverty, income equality and gender inequality” (BUDG and ECON 2020a, 29).

Even more importantly, our analysis of the amendments revealed a coordinated cross-party effort to further strengthen the gender perspective of the European Commission’s gender-blind proposal. FEMM’s gender mainstreaming amendments—which tend to be disregarded by other committees—were this time amplified by members of the economic and budgetary committees from different political groups. These politicians, some of whom were also FEMM members, made the same amendments in their own name or in the name of their political group and thus increased the visibility and legitimacy of the FEMM Committee’s views. In addition, a cross-party coalition consisting of key gender equality actors from the social democrats, the EPP, and the left group made several amendments that echoed the ones put forward by FEMM.

We interpret these coordinated efforts as the Parliament’s feminist actors having learned from the previous economic crisis and wanting to avoid the invisibility of gender perspectives that characterized that crisis (cf. Guerrina Reference Guerrina, Kantola and Lombardo2017; Jacquot Reference Jacquot, Kantola and Lombardo2017). Our analysis suggests that it was the cross-party collaboration of feminist actors in the budget and economic affairs committees, rather than the established channels for gender mainstreaming, such as the FEMM Committee’s amendments, that enabled the integration of gender perspectives. Comparisons of the amendments and the adopted report reveal that the gender amendments were most successful when the FEMM Committee’s proposals were amplified by economic and budget committee members from several groups, including from the EPP. The politicians who sat in both the FEMM Committee and the committees in charge of the recovery fund played a crucial role in disseminating gender perspectives across committees and can be seen as critical actors (see Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009) who were particularly important for the positive outcomes.

Beneath the surface of these cross-party efforts, ideological differences and political struggles between the groups influenced the outcome. Measured by the number of gender and care-related amendments, the greens (29 amendments) and the social democrats (22) were most engaged in gender mainstreaming. The EPP (7), liberals (5) and left (4) groups, which had been relatively vocal about the gender impacts of COVID-19 and the need to gender mainstream the recovery instruments within the FEMM Committee, paid significantly less attention to gender when it came to the actual decisions about money in other committees. Unsurprisingly, the radical right populists, which had opposed references to gender in FEMM, did not make any gender-related amendments.

There were differences between the groups’ approaches to gendering the crisis response, too. In general, the comprehensive constructions of the crisis as gendered that were prominent in the FEMM report were replaced by attempts to integrate gender equality into the recovery fund’s scope and objectives, with a view toward ensuring that the money could be used to promote gender equality and address the gender impacts of the crisis. Most parliamentarians also made amendments with the goal of ensuring that member states would have to take gender equality into account in their national spending plans. The main conflict concerned care and the understanding of recovery. The FEMM Committee and some members of the budget and economic committees used the concepts of care and care economy to push for a change in the dominant understandings of recovery. Their amendments drew attention to the role of “investment in robust care infrastructure” in building a resilient society, stressed “protection of the care economy as an essential part of the economic model,” and called for a “care transition” alongside the original emphasis on green and digital transition (FEMM 2020c). The emphasis on the care economy can be seen as a feminist and transformative response to the crisis that goes beyond the narrow understandings of the economy implied in the EU’s recovery instruments. It is therefore not surprising that the issue was politically divisive. Only the greens and the cross-party coalition of feminist politicians made amendments about the care economy and care transition. The left group, which had advocated for a care deal in the FEMM Committee, and the center-right groups did not address care.

The outcome of these gender mainstreaming efforts was limited to provisions that can be assessed as feminized rather than feminist. Parliament’s adopted position on the recovery fund integrated gender equality into the fund’s objectives—not as broadly as the promotion of gender equality proposed by the FEMM Committee and many individual parliamentarians, but as “mitigating the social and economic and gender-related impacts of the crisis” (BUDG and ECON 2020b, 23). Another success was that the Parliament’s position made strong gender mainstreaming requirements for the national spending plans: they should, for instance, be based on a gender impact assessment and comprise actions to address the gendered impacts of the crisis as well as gender mainstreaming measures (BUDG and ECON 2020b, 33, 35). In contrast, the transformative amendments on the care economy were not adopted. The role of care in recovery and the need to invest in care infrastructure were only acknowledged in the introductory part of the text that does not have legal implications for the use of the recovery money (BUDG and ECON 2020b, 8).

The final agreement about the recovery fund between the Parliament and the member states contained only part of Parliament’s gender-related demands. Mitigating gender-related impacts of the crisis changed to “mitigating the social and economic impact of that crisis, in particular on women” (Official Journal 2021, 31), and the several paragraphs on the national plans and their implementation and monitoring shrank to one paragraph. The changing of “gender” to “women” is an example of some countries’ (Hungary and Poland) opposition to “gender ideology” in the Council of the European Union. Although the influence of anti-gender forces on gender mainstreaming in the European Parliament remained small, opposition to gender equality reappeared in interinstitutional negotiations.

Overall, our analysis shows the resilience of gender mainstreaming as a tool of feminist governance during the COVID-19 crisis, in contrast with the failures of the previous economic crisis. The crisis context had enhanced awareness of the importance of gender mainstreaming, and the integration of gender perspective to the recovery fund benefited from cross-party support of feminist actors within the economic and budget committees. Although the successes were limited to technical, feminized provisions, our findings suggest that gender mainstreaming works in times of crisis, even in the hostile field of economic policy.

Conclusions

This article has approached the European Parliament’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic by assessing how effectively its feminist governance framework worked in gendering the crisis. We focused on two of the most relevant aspects of feminist governance in the context of the Parliament, namely, the FEMM Committee and gender mainstreaming. The failure of the Parliament to gender the policy response to the previous economic crisis from 2008 onward provided an important context for the endeavor.

The use of the concept of feminist governance allowed us to focus on two aspects in the process of gendering the crisis. One was an institution—Parliament’s main gender equality body, the FEMM Committee. The other—gender mainstreaming—was a policy-making tool. The concept of feminist governance brings these two together and allows for comparing their role and effectiveness. The FEMM Committee was an institution in which parliamentarians could formulate feminist responses to the crisis. This was well illustrated by our analysis, which showed the breadth and depth of issues that the FEMM Committee’s report on the COVID-19 crisis engaged with. Even if the committee also hosted anti-feminist parliamentarians, their opposition was sidelined and did not impact the final report. Gender mainstreaming, by contrast, is a tool for feminist governance, which is used in completely different contexts. In this article, we analyzed how it was applied to the EU’s economic crisis response in the traditionally hostile field of economic policy, in the context of two committees resistant to the integration of gender perspectives. We have argued that here even a feminized—rather than feminist—response counts as a success of feminist governance. Our analysis showed that unlike in the 2008 economic crisis, the European Parliament did manage to mainstream a gender perspective into crisis response policies, even if its feminist governance framework faced additional challenges because of the way the pandemic restricted parliamentary work.

The feminist governance concept allows for analyzing the linkages between the institutions and policy-making tools for promoting gender equality. The FEMM Committee is a space for feminist knowledge building and debate, for testing and developing ideas, and for fostering cooperation and networks. These can be immensely helpful when seeking to implement gender mainstreaming in contexts and policy fields that are more resistant to gender equality. Our findings also suggest that a strong feminist governance institution alone, such as the FEMM Committee, is not enough to gender a crisis such as the pandemic. Importantly, coordinated cross-party efforts from gender advocates (many of whom are also FEMM members) took place in the Parliament’s economic and budgetary committees to support FEMM’s position and insert gender in the European Commission’s gender-blind recovery plans. These politicians can be seen as critical actors crucial for the integration of gender perspectives. While our analysis showed that, compared with the FEMM report, these were watered-down versions and rather technical in terms of their approach to gender mainstreaming, there were some eventual successes. Despite the bleak picture at the start of the crisis, the legislation establishing the recovery fund came to contain requirements for gender mainstreaming. While gender perspectives were not silenced, they could only be integrated to the extent they did not challenge existing investment priorities and the narrow understandings of the economy these priorities rely on.

While the implementation of these measures will take place in the months and years to come and be the real test for gender mainstreaming, the agenda-setting phase shows some contemporary successes for gender mainstreaming in times of crisis. This may call for reassessment of some of the more pessimistic analyses of the fate of gender mainstreaming and gender equality in the EU (Abels and Mushaben Reference Abels and Mushaben2020). It highlights the importance of work and collaboration behind the scenes and across political group lines.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by European Research Council (ERC) funding under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program grant number 771676.