Introduction

Therapeutic radiographers undertaking on-treatment review clinics provide continuity of care for radiotherapy patients and reduce workloads for clinical oncologists and registrars. Reference Murray, Gilleece and Shepherd1 Radiographer-led review clinics help the patient fully understand the written information regarding their treatment and assure them that their radiotherapy is integrated correctly into their overall treatment plan. Radiographers monitor patients’ radiotherapy tolerance, reactions and manage treatment-related toxicity including providing advice and treatment regarding radiation reactions. Reference Murray, Gilleece and Shepherd1 They co-ordinate the multidisciplinary team and make appropriate referrals to the Clinical Research Radiographer, Information and Support Radiographer, Macmillan Support and Information Service and a variety of allied health professionals. Since the existence of COVID-19, these beneficial clinics have had to adapt to ensure patients continue to receive information and support during their treatment while limiting their potential exposure to COVID-19.

Telephone reviews for patients are not novel and indeed pre-COVID-19 were becoming an increasingly common feature in the modern healthcare setting. Reference Gonzalez, Cimadevila and Garcia-Comesaña2 ‘Telemedicine’ is described as activities involving ‘two-way, real-time interactive communication between the patient and practitioner at a distant site’. Reference Chaet, Clearfield, Sabin and Skimming3 They consist of three phases: gathering information, cognitive processing and output. Reference Chaet, Clearfield, Sabin and Skimming3 This template is similar to the traditional structured face-to-face interviews. Nowadays, in the post-COVID world, upwards of a quarter of all care consultations are conducted by telephone. Reference Vaona, Pappas, Grewal, Ajaz, Majeed and Car4 One study suggests that telephone reviews can effectively replace face-to-face reviews in roughly 10% of cases Reference Gonzalez, Cimadevila and Garcia-Comesaña2 ; the concern is that for the other 90%, telephone may not be effective, with few alternatives amid a pandemic. A telephone review may not be as satisfying for a patient compared to a face-to-face consultation. Reference Gupta5

The aim of the narrative review is to explore the subject of telephone reviews and how therapeutic review radiographers might need to adapt communication skills so that they can continue to effectively assess and manage radiotherapy patient treatment reactions remotely.

Method

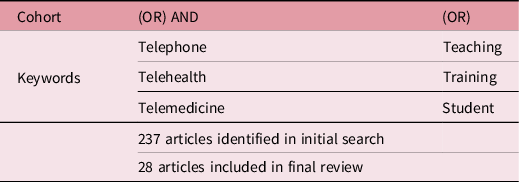

The narrative literature review examines literature regarding telephone reviews and specific training/teaching of associated skills. The SCOPUS database was searched using a variety of title keyword combinations (Table 1). While telephone review is not always regarded as telehealth, Reference Rutledge, Kott, Schweickert, Poston, Fowler and Haney6 due to the wide variability in definition, the keywords ‘telehealth’ and ‘telemedicine’ were included to capture publications of all types which discussed skills/training required in healthcare telephone reviews. The date range was set from 2013 to January 2021 to include more recent publications. Articles were rejected if they were not related to the healthcare system or had literature related only to virtual consultations. A total of 237 article abstracts were reviewed with 94 of the publications read in full. Twenty-one articles were deemed relevant to the discussion and were included along with seven additional references which were discovered from within the 21 articles. A total of 28 publications are included in the review. The authors acknowledge that the narrative review, by its very nature, is not a systematic review and therefore provides only a focused sample of literature on the subject, however, it does serve to inspire debate and deepen understanding.

Table 1. SCOPUS database search strategy and hits

Discussion

Health professionals’ experience of telehealth review

Gupta (2013) Reference Gupta5 commented that essential information for forming a diagnosis could be missed through telephone consultations, due to the absence of nonverbal communication such as facial expressions, body language and eye contact. The absence of these cues provides unique barriers to communication and the inability of reviewers to exercise professional skill and judgement. Reference Irvine, Drew and Bower7 Consequently, review radiographers can no longer rely on eye contact and body language to read patients’ comprehension and satisfaction, but instead they must rely on subtle changes in the tone of the patient’s voice. Differences in communication patterns such as pace and type of discourse, and reliance on visual cues by both provider and patient, especially in communicating empathy, Reference Henry, Block, Ciesla, McGowan and Vozenilek8 can increase the risk for distractions, misunderstandings and difficulty in building rapport with a patient. Background noises and service system failures are other complications that can make telephone interactions challenging. Reference Yliluoma and Palonen9 Furthermore, the modest handshake that a reviewer would normally use to greet a patient and convey respect can no longer be practised.

Some patients can show reluctance to convey their issues through a telephone review. Patients demand time, information and want their questions to be answered. They expect politeness, empathy and human touch Reference Shendurnikar and Thakkar10 but it can be extremely challenging to recognise and understand feelings through the tone of a patient’s voice and empathise accordingly. A qualitative study of 15 patients by Knudsen et al. (2018) Reference Knudsen, de Thurah and Lomborg11 reported that while many patients enjoyed the flexibility and convenience of telephone reviews, some patients found it easier and more comfortable to talk about their problems face-to-face. These ‘reluctant patients’, as they were categorised by Knudsen et al., valued the interrelatedness, feeling that the contact served to build a closer relationship with their health professionals and viewed telephone communication as a reduced form of conversation, leading to a distanced relationship. The study found that in these patients there was a perception that the telephone follow-up benefited the system rather than the individual and they felt that they were treated as a ‘number’ rather than a person. Reference Knudsen, de Thurah and Lomborg11 Attila (2017) Reference Attila12 interviewed 58 physicians, mainly radiologists, discovering that radiologists too felt that telephone reviews depersonalised the doctor–patient relationship, often to the point where it almost terminates, resulting in incomplete clinical information being acquired. In contrast to these findings, Rodler et al. (2020), Reference Rodler, Apfelbeck and Schulz13 who received survey responses from 92 of 101 uro-oncologic patients (92% response rate) regarding telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, found this consultation method to be highly accepted. They acknowledged that while hearing impairment was a barrier in telehealth, virtual communication and help from relatives aided in alleviating this barrier. However, the majority of patients felt that this method of review would not be favourable after the acute crisis of COVID-19 has passed. Reference Rodler, Apfelbeck and Schulz13 Therefore this study, in alignment with the previous studies, demonstrates that patients feel that face-to-face reviews are very important, particularly where treatment decisions are being made. The study determined that patients ultimately value personal interactions with health professionals and concluded that telephone reviews should be balanced between the need for distancing and sustaining personal patient relationships which is also applicable to patients undergoing radiotherapy and attending radiographer-led treatment review clinics.

Interestingly, Larson et al. (2018), Reference Larson, Rosen and Wilson14 who conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of telehealth reviews with adult cancer patients, concluded that telehealth reviews in conjunction with supplementary interventions, are at least as effective at improving quality of life scores in patients undergoing cancer treatment as in-person reviews. Eleven eligible studies were included where a measurable global quality of life scale or questionnaire was utilized. Reference Larson, Rosen and Wilson14 They concluded that an added benefit of telehealth reviews was the ability to reach patients in rural locations who may struggle to attend in-person appointments. A limitation of the review was the small number of studies and the fact that 6 of the 11 included studies involved only breast cancer patients, the findings may therefore not truly reflect the experiences of patients with a diversity of complex issues associated with a variety of cancer diagnoses.

Health professional training to address telephone review skills

The Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) Standards of proficiency for radiographers, paragraph 8, state that radiographers must be able to communicate effectively. Health professionals routinely receive training in communication skills, but this does not necessarily include the specificities of telephone communication. Reference Seale, Ragbourne and Purkiss Bejarano15 Some of the reviewed literature, mainly related to medical training, have assessed the short-term effect of interventions aimed at improving telephone consultation skills.

Medical training

Saba et al. (2014) Reference Saba, Chou and Satterfield16 studied and assessed the outcomes of a specific model of phone communication training within healthcare, implementing a ‘Telephone Follow-up Curriculum’ which encouraged students’ patient-centred skills. Students and faculty both reported improvement in students’ understanding of, and attitudes towards telephone follow-up. The majority of students agreed or strongly agreed that they learned about patient health behaviours (77%), that their ability to provide patient education improved (71%), and that these communication skills will be relevant to future patient encounters (94%). Reference Saba, Chou and Satterfield16 More recently, Seale et al. (2019) Reference Seale, Ragbourne and Purkiss Bejarano15 conducted a study with 50 undergraduate medical students where half of the students undertook specific telephone training (combination of 1 h session including PowerPoint and a practical component) followed by a short simulation session 7–14 days later. All 25 students felt positive about the learning experience and felt they would use aspects of the training in their role as junior doctors. Compared to the untrained group, students felt more confident and prioritised their job list in alignment with the clinical skills team. Reference Seale, Ragbourne and Purkiss Bejarano15 However, some gaps were still identified in the trained group and the authors concluded that more extensive education and practise of these skills was required. All students agreed that this specific telephone teaching was an important component and should be added as a standard within medical programmes. Reference Seale, Ragbourne and Purkiss Bejarano15

Hindman et al. (2020), Reference Hindman, Kochis and Apfel17 using a convenience sample of third-year medical students, divided students into a control and intervention group where the intervention involved teaching of specific telephone medicine curriculum. Students in the intervention group had a significantly higher mean score on a simulated Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) compared to the control group. Jonas et al. Reference Jonas, Durning, Zebrowski and Cimino18 also piloted a tailored telehealth curriculum for 149 third-year medical students finding similar results. McDaniel et al. Reference McDaniel, Molloy and Hindman19 developed telephone triage curriculum for their 3rd and 4th year medical students (74 students) where students self-reported that this teaching increased their knowledge (73%) and was engaging (86%). Other authors who have provided evidence-based models for integration of telehealth curriculum into their medical programmes include Pathipati et al., Reference Pathipati, Azad and Jethwani20 Rienits et al., Reference Rienits, Teuss and Bonney21 Vasquez-Cevallos Reference Vasquez-Cevallos, Bobokova, Bautista-Valarezo, Dávalos-Batallas and Hernando22 and Walker et al. Reference Walker, Echternacht and Brophy23

Omoruyi et al. (2018) Reference Omoruyi, Dunkle, Dendy, McHugh and Barratt24 explored the challenges of telecommunication for patients requiring interpretation due to language barriers and stressed the need for educational interventions, which consider this aspect of patient care. They specifically looked at the impact of introducing a 1-hour interactive educational intervention to medical students regarding issues related to live versus remote interpreter management. Utilising control and intervention cohorts, they reviewed students’ telephone interpreter skills using actual patient encounters post-intervention. In comparison to the control groups, the intervention group felt more competent, provided clearer information at the optimal pace and excelled in closing out conversations appropriately.

Veterinary training

Sheats et al. Reference Sheats, Hammond and Kedrowicz25 who analysed 25 phone calls of final year veterinary students, also identified gaps in their telephone communication, concluding that specific education is needed to improve case review, preparation in addressing questions or concerns, following of organisational protocols along with listening and reflection skills related to demonstration of empathy. Grevemeyer et al. Reference Grevemeyer, Betance and Artemiou26 stress the importance of specific telephone training for veterinary students and discuss their programme which incorporates the Calgary–Cambridge Guide (CCG) as a conceptual framework for this tailored communication skills training which includes practically simulated telephone communication.

Nurse training

Chike-Harris Reference Chike-Harris27 discusses the integration of telehealth into a nursing programme curriculum using eight competencies provided by the National Organisation of Nurse Practitioner Faculties for telehealth education. Telehealth curriculum including didactic and simulated learning was integrated into all years of the nursing programme. Student pre-test/post-tests scores increased significantly and the feedback from students was very positive. The potential requirement for early education in this area of practice was evidenced by Glinkowski et al. Reference Glinkowski, Pawłowska and Kozłowska28 who found, through surveying nursing students, that only the final year students believed telenursing may improve nursing practice, years 1 and 2 students may require further education regarding the benefits. Lister et al. (2018) Reference Lister, Vaughn, Brennan-Cook, Molloy, Kuszajewski and Shaw29 and List et al. (2019) Reference List, Saxon, Lehman, Frank and Toole30 through modifying their nursing curriculum to include telehealth, demonstrated that even small modifications to the existing curriculum can improve student confidence in this aspect of their practice. Other nursing programmes incorporating telehealth simulation have also demonstrated improvement knowledge gain through this adaptation of curriculum Reference Mennenga, Johansen, Foerster and Tschetter31 . Rutledge et al., Reference Rutledge, Kott, Schweickert, Poston, Fowler and Haney6 based on their experience, outline a range of comprehensive topics and techniques which they advocate including in telehealth nursing curriculum.

Allied health professional (AHP) training

Few studies in the narrative review included AHP-specific telephone skills training. Gustin et al. Reference Gustin, Kott and Rutledge32 describe the implementation of online learning and simulated training within an interprofessional module including advanced practice nurses, graduate health professionals and undergraduate dental hygiene students (103 participants). This intervention demonstrated improvement in all aspects of knowledge and students scored higher in their simulation encounters post-intervention. However, it should be noted that this education focused more on video communication rather than telephone communication though arguably these skills would apply to both scenarios. Gustin et al. Reference Gustin, Kott and Rutledge32 conclude that, based on student comments and pre-intervention knowledge scores, there is a strong need for training in telehealth in all healthcare professions. The study supports the notion that telehealth etiquette is not intuitive and needs to be formally taught as part of all healthcare programmes. Randell et al. Reference Randall, Steinheider and Isaacson33 also assessed a telehealth intervention as part of an interprofessional curriculum including occupational therapists, physiotherapists and student nurse practitioners. They concluded that the intervention resulted in increasingly positive perceptions regarding the use of telehealth for patient review though qualitative student data indicated that students perceived telehealth as ‘an added barrier to interacting with the patient and with other members of the team’ (p. 350). Reference Randall, Steinheider and Isaacson33 Randell et al. also focused on video communication rather than telephone communication.

The narrative review demonstrates that while there may be a limited number of publications specifically addressing telephone skills training in allied health professions, including therapeutic radiography, there is a strong need for specific high-quality training in the area. While telehealth, including telephone skills training, is increasingly being integrated into healthcare programmes, Reference Camhi, Herweck and Perone34 this appears to be mainly occurring in medical and nursing programmes. Publications reviewed consistently demonstrate that the development and integration of evidence-based telephone skills training, improves student confidence, awareness, knowledge and skills in this area of practice. Reference Vaona, Pappas, Grewal, Ajaz, Majeed and Car4 Ideally the training might be incorporated into all years of undergraduate therapeutic radiography programmes Reference Saba, Chou and Satterfield16 with a combination of multiple teaching modalities including didactic and simulated teaching. Reference Vaona, Pappas, Grewal, Ajaz, Majeed and Car4,Reference Stovel, Gabarin, Cavalcanti and Abrams35 Simulated teaching ideally would involve the use of standardised patients and cover areas including the importance of ‘appearance, distractors, privacy, nonverbal and verbal communication and strategies to effectively express empathy’ (p. 89). Reference Gustin, Kott and Rutledge32 This tailored learning may be ideally placed in interprofessional modules throughout the curriculum as all allied health professionals need to develop effective communication skills.

While the majority of studies focused on the student outcomes and demonstrated very positive findings, very few studies actually explored how the learning translated to the quality of patient experience. More research might be undertaken to assess current therapeutic radiography training with direct assessment of its impact on patient care. Moving forward, aptly chosen patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) may prove useful to enable evaluation of long-term retention of skills and tangible benefits to patient quality of care. Few studies to date have captured the experiences of patients post-training and determined the true benefit of training to the patient experience and wellbeing.

There is an opportunity within telehealth to enhance access to care, quality of care and satisfaction for both patients and reviewers. Reference Rodler, Apfelbeck and Schulz13 While health professionals routinely receive training in communication and reviewing skills, this does not necessarily include the specificities of telephone communication. Telephone reviews require the same degree of thoroughness and careful clinical judgment as face-to-face consultations. The standards of education and training for higher education programmes might be refreshed by the HCPC to ensure that student radiographers are achieving refreshed standards of proficiency in this dimension of communication. The student standards of proficiency might be evidenced through simulated practice moderated by experienced therapeutic radiographers. Reference Chambers, Hickey, Borghini and McKeown36

It is well established that therapeutic radiographers should be well prepared, engaged and courteous when undertaking reviews. They should be friendly and warm and not make patients feel rushed. Reference Vidal-Alaball, Acosta-Roja and Pastor Hernández37 Asking open-ended questions, effective listening, appropriate praise, providing enough information as part of advice and finally checking the patient’s understanding, are all key areas of communication during a review. Reference Shendurnikar and Thakkar10 Ultimately, therapeutic review radiographers may need further training in telehealth to enhance their communication skills and so make up for the lack of visual stimuli. Reference Rothwell, Ellington, Planalp and Crouch38 Understanding the barriers that inhibit radiographer and patient communication can provide an opportunity to eliminate them. Radiographers need to acquire telehealth consultation skills in order to thrive in an increasingly pressurised health system that demands the delivery of high-quality, high-volume health care within the confines of a shrinking health care workforce. The distinct differences between telehealth and face-to-face consultations necessitate a need to provide guidelines and recommendations to educate both health professionals and patients on how they can best participate in telephone reviews. Reference Vidal-Alaball, Acosta-Roja and Pastor Hernández37 The use of competency-based training for telephone reviews will facilitate high-quality, safe and effective consultations Reference Lum, van Galen and Car39 especially if telehealth becomes the new post-COVID-19 normal.

Conclusion

On-treatment reviews, whether face-to-face or on the telephone, between therapeutic review radiographers and patients are about human connection and engagement and should always be viewed as such to provide compassionate, high-quality care to patients and their loved ones. Reference Houchens and Tipirneni40 Telephone reviews can be convenient and effectively resourceful for both radiographers and patients, but communication barriers do exist which can limit the ability of telehealth to match certain aspects of the face-to-face review clinics. The long-term effects, such as the apparent safety afforded by home-based reviews during the pandemic and the effectiveness of telephone communication for patients undergoing radiotherapy, are yet to be fully realised. Reference Leung, Lin, Chow and Harky41 Multiple teaching modalities including simulation are ideal for teaching telephone-specific skills and content, demonstrating improvement in student knowledge, competence and confidence.

Perhaps there is a requirement for a nationwide consultation event to seek the views of radiographers, stakeholders and service users regarding how to strengthen the standards of proficiency aligned to telehealth/telephone communication. Reference Chambers, Hickey, Borghini and McKeown36 Future studies might focus on investigating further the type of teaching methods needed whilst developing telephone consultation models and validating assessment tools. Reference Van Galen, Wang, Nanayakkara, Paranjape, Kramer and Car42 PROMs may be a useful undertaking for future training evaluations to help determine that effective patient care is being maintained. Given that remote consultation is becoming more prevalent, it would appear to be good practice to development and enhance the telehealth curriculum in therapeutic radiography.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Northern Ireland Cancer Centre, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, for their support.

Financial Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.