Introduction

What role does the media play in the development of speculative bubbles on financial markets? The issue has received much scholarly attention in recent years, not the least in the wake of the most recent financial crisis.Footnote 1 The issue is, however, far from new, and it has attracted the interest of some economic and business historians, such as Campbell, Turner, and Walker studying the media’s role during the British Railway mania of the 1840s.Footnote 2 This bubble occurred during a time when financial markets were developing at a rapid pace in some of the leading economies of the world. The City of London during the nineteenth century would take center stage for developing global financial markets, a position it would retain well into the twentieth century.Footnote 3 The globalization of the world economy during the nineteenth century added a new level of complexity to investment decisions. Investors now had to make investment decisions concerning business opportunities or ventures that they might never see for themselves.Footnote 4

The challenge of acquiring reliable information increased drastically, especially for the least developed economies of the time, such as those in Africa. In this article, we explore this issue through a case study of the two “Jungle” bubbles of the early twentieth century. On the London Stock Exchange, the term Jungle was the informal (and belittling) label that traders and the financial press put on a section of the exchange trading in stocks of West African mining companies around 1900. We focus on one such company in particular, the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation, as this was an important company operating in West Africa during the colonial period, and the single largest of the Jungle companies at this time.

The company experienced two major boom-and-bust cycles in its early history, and this article studies the development of these cycles, and in particular what role the financial press played in these bubbles. The financial press faced major challenges in trying to report on businesses operating in geographically peripheral markets because of a lack of independent reliable sources. This often forced newspapers to report on Ashanti Goldfields based on no or few sources other than what the company itself provided. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the reporting often failed to provide readers with much of the factual information needed to make well-informed decisions, and many times the press seemed to be influenced by the speculative waves. The Ashanti Goldfields case study indicates that the coverage by the financial press might have unintentionally fueled the boom-and-bust cycles on the West African market at this time.

Previous Research

It is well known that markets, not the least financial markets, are highly sensitive to information flows. The development of information and communication technologies have been pivotal for modern economies,Footnote 5 and crucial for globalizing the world in the nineteenth century. Klas Rönnbäck has shown that prior to the rise of new technologies, it could take five to six months for a letter from West Africa to reach Europe, and more than two months for a letter from the Caribbean.Footnote 6 New information and communication technologies, such as the telegraph, thus played enormously important roles in speeding up transmission times and affecting the development and growth of global financial markets.Footnote 7

Victorian legislation in Britain—the world’s leading financial market at the time—imposed few requirements on companies concerning the disclosure of information, even to its shareholders. Jean-Jacques van Helten has argued that ordinary investors in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries rarely knew the net worth of a company.Footnote 8 Investment groups became an important way to handle the uncertainties involved in making investments.Footnote 9

The development of European economies during the nineteenth century created a rapidly growing demand for raw materials, including metals, and thus an increasing share of international investment targeted this sector in particular.Footnote 10 Mines, however, were fraught with uncertainties. Mining engineering, which became increasingly professionalized, could in theory reduce some of the uncertainties—and hence risks—involved in developing mines.Footnote 11 This was not always the case, however, as even some engineers became involved in highly dubious ventures.Footnote 12 But the mining, more than any other sector, also suffered from major information asymmetries between company promoters and managers, on the one hand, and investors, on the other, as the latter usually did not have access to the same information as the former. According to Van Helten, professional speculators held many of the shares in the growing mining sector.Footnote 13 These speculators did, however, sell assets to a broader group of outside investors in order to raise large amounts of capital. Ian Phimister and Jeremy Mouat have argued that these outside investors were “more vulnerable to market manipulation” because they might not have access to the information concerning a mining venture to begin with or have the capabilities necessary to interpret the information, if they had access to it.Footnote 14

For these investors, the financial press became all the more important as a potentially independent, impartial, and reliable source of information. Unsurprisingly, there were many accusations that the early financial press was often inaccurate or biased, and sometimes outright corrupt, in its reporting.Footnote 15 Modern research has, however, suggested that the early financial press, despite its challenges, provided mostly unbiased and factual information to its readers.Footnote 16 The research on the historical development of the financial press has focused on how well the media reported on domestic business ventures in the European centers of finance, such as the above-mentioned British Railway mania in the 1840s.Footnote 17 However, Charles Harvey and Jon Press have stressed that one reason London became the global financial hub during this period was the large amount of information available via the London financial press.Footnote 18

The challenge of reporting unbiased and factually accurate information in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was especially true when it came to business ventures in emerging or peripheral markets overseas, such as in Africa. African business history has received increasing scholarly attention in recent years.Footnote 19 This article contributes to this field by focusing on investments in businesses in the African periphery during the early twentieth century. Investments in Africa to a large extent targeted the mining sector, and the vast share of investors targeted South Africa. These particular mining investments have been studied in previous research, including speculative booms such as “Kaffir boom” in South African mining in the 1880s and 1890s, when many ordinary investors faced severe information asymmetries.Footnote 20

In this article, our focus is on a less researched historical speculative boom in Africa; namely, the boom in West African mining, the so-called Jungle market on the London Stock Exchange in the early twentieth century, and the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation. This was the largest of the Jungle companies on the London Stock Exchange in terms of market capitalization, and in terms of longevity and magnitude of its operations, one of the most important companies operating in Ashanti (current-day Ghana) during the colonial and early postcolonial era. Given the importance of mining companies in the history of Africa, there is remarkably little written on the business history of Ashanti Goldfields. This is not for lack of archival sources. T. C. McCaskie has undertaken research on the start of the company in the early 1890s.Footnote 21 In 1988 Raymond Dumett published a guide to the large archives of the company.Footnote 22 Dumett also studied early investors in the company, arguing that several of them were among “the most notable members of the gentlemanly capitalist elite of Britain.”Footnote 23 Dumett and Jim Silver have in parallel studied the failure of several other mining ventures operating in this region around the same period of time.Footnote 24 Sources from the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation’s archives have been used by Ayowa Afrifa-Taylor for an in-depth study on the long history of the company, from its start to the twenty-first century.Footnote 25 Aspects of the company’s more recent history, from the period of decolonization onward, have also been studied in other research.Footnote 26 Previous studies on the historical return on investments in companies operating in the colonies include Ashanti Goldfields, as do some recent overviews of African business history, albeit only briefly.Footnote 27 The company’s development during the Jungle boom, however, has not been the focus in any of this research.

The London Stock Exchange was not only the largest centralized financial market place in the world but also its regulatory environment differed from most of its global competitors. Since its inception in 1801, the Exchange had profiled itself as open to financial innovations in a relatively lax regulatory environment. In combination with the dominant position of the United Kingdom in the world economy during the latter half of the nineteenth century, the number of Exchange members and the number of assets they traded skyrocketed.Footnote 28 The recurrent boom-and-bust cycles of the Exchange spurred discussions on regulating it, but it was not until the problematic years of the 1910s—in the wake of World War I—that any serious discussion on tighter regulation gained traction. As for rules on information disclosure, there were few requirements prior to the 1920s. New legislation on companies in 1928 and 1929 attempted to enforce rules of greater disclosure, but the measures had few long-term effects.Footnote 29

Methods and Sources

In this article, we study the interplay between investors and the London financial press. Previous research on the topic has employed time series analysis to test the media’s role during speculative bubbles econometrically.Footnote 30 In contrast, we employ a qualitative case study methodology, which allows us to analyze in greater depth the media’s reporting on the particular case under study, making our article a valuable complement to these econometrically based studies. Our study is, as was noted above, the Jungle bubbles of 1898 to 1901 and 1909 to 1910. Our work is on Ashanti Goldfields during this period as a major company operating in West Africa during the colonial period, and the single largest company in what came to be called the Jungle—West African mining—section of the London Stock Exchange. This is a case study of the media’s role during bubbles on an emerging, peripheral market, and employs two sets of sources: (1) quantitative data on the total return on investments in the company’s equity as an indicator of what the general investors perceived of the company’s performance, and (2) qualitative data on the reporting on the company’s performance in the London financial press.

We study the quantitative data—the company’s financial performance—from the perspective of the investors. These data are based on the total return on investments, including share price appreciation or depreciation as well as dividends paid out, for the company’s equity traded on the London Stock Exchange. The data comes from the African Colonial Equities Database,Footnote 31 which is based on the end-of-month price of stocks from the Investors’ Monthly Manual (IMM), collected by Global Financial Data, and on the dividends paid out as reported in the London Stock Exchange Yearbooks, starting when the company started to be included in the IMM in June 1901. We also use our own empirical data on the price of the shares from November 1898 to May 1901, which is prior to when the company started to be included in the IMM. This data was assembled from the columns of the Financial Times in a section appearing twice monthly under the heading “Mining Carry-Over.” The quantitative data thus, as noted above, lets us review how well the company performed from the perspective of an investor. This will, to some extent, be related to the company’s performance, for example, when it comes to its mining output, but the financial performance also depended on other factors discussed in the article.

The qualitative empirical data are based on the reporting on the company in the Mining Journal, The Economist, and the Financial Times. The indices of the Mining Journal for all years during the period under study (1895 to 1914) were used to find articles concerning to the company. References to the company were only indexed when it was the main focus of the article, so it is not possible to find brief references to the company under more general headings (e.g., reporting on the development of the stock market). As a partial remedy, general references in the indices for the terms Ashanti, Gold Coast, and West Africa were also looked up. As for The Economist and the Financial Times, the entire historical archives of these two publications have been digitized and made searchable online, so any reference to the company anywhere in these publications can be found. We searched these digital archives for any news clippings mentioning the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation during the period under study. Unrelated companies with similar names have been excluded from the sample. The search yielded a result of 246 news clippings from The Economist and 1,897 news clippings from the Financial Times, for a total of 2,143 news clippings from these two publications. Ashanti Goldfields was frequently noted in the London financial press, and a regular reader of these newspapers would hardly have failed to notice the company’s existence.

We analyzed all the clippings to gather our qualitative empirical data. The majority of the clippings from the Financial Times are brief reports on how the company’s equity was performing on the London Stock Exchange, which were generally included in daily or weekly round-ups on the trading on the London stock market. These often included little information aside from how the share had changed—or not changed—in price. A large number of clippings in all three newspapers did, however, include valuable information on how the company was performing, often describing in detail the underlying factors determining this performance. These sources in effect captured the annual reports of the company, as the newspapers reported extensively on the contents of the annual reports as well as on the dealings during shareholders’ meetings.

Quantitative Evidence of Company Performance

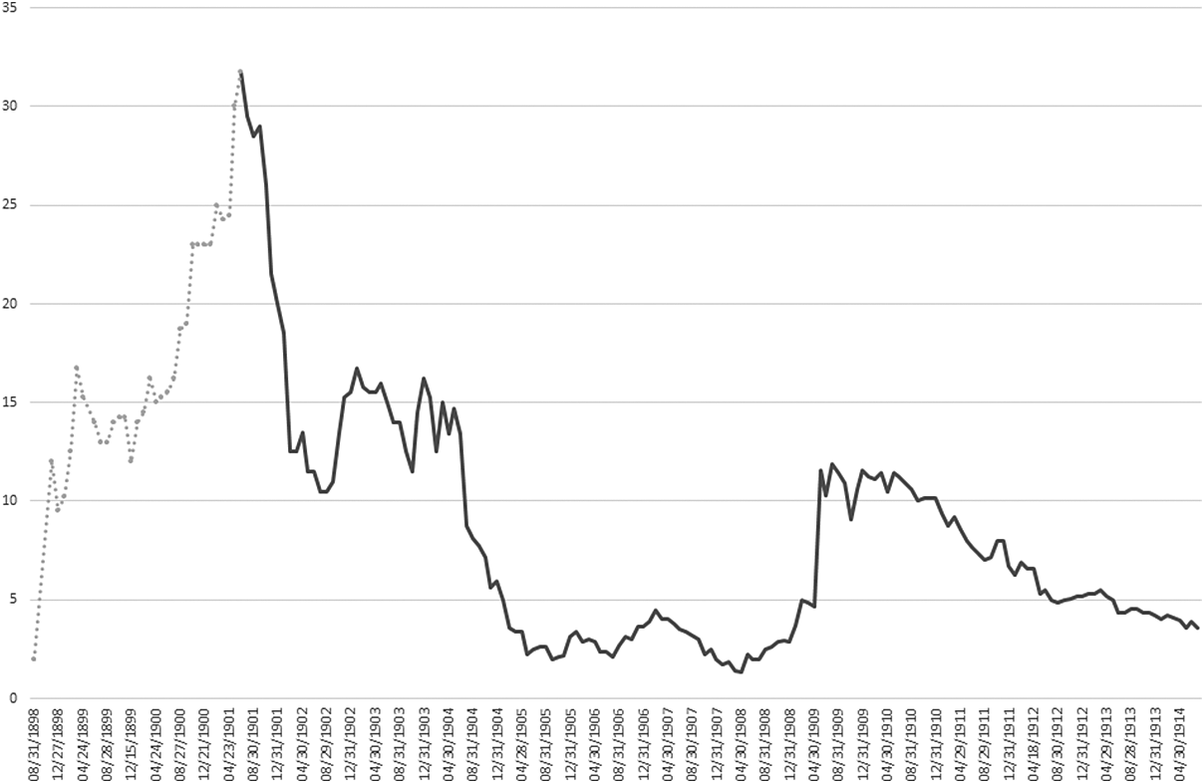

The Ashanti Goldfields Corporation was established in 1897, at which time it acquired a concession for gold mining in Ashanti (current-day Ghana) from the Côte d’Or Company. Mining operations began for real in the following year, 1898.Footnote 32 Figure 1 shows data on the price of the company’s shares on the London Stock Exchange from 1898 (when it was first publicly offered) to 1914. It should be noted that the data for September and October 1898 has been interpolated. In January 1904, the shares were split (one share split into five), which is reflected in the price quotations in the sources. We have adjusted for this, so that nominal prices from 1904 onward have been multiplied by five.

Figure 1 Price quotations for Ashanti Goldfields shares, London Stock Exchange, by month, 1898–1914 (£ per share, split-adjusted)

Sources: Data for August 1898, Afrifa-Taylor, “Economic History of the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation,” 241; for November 1898–May 1901, “Mining Carry-Over,” Financial Times Historical Archive; from June 1901 onward, Global Financial Data.

As seen in figure 1, there were drastic changes in the price of the shares over time. This is reflected in the total return on investments in the company, as shown in figure 2.Footnote 33

Figure 2 Accumulated real return on investments in Ashanti Goldfields, and portfolios of other African shares on the London Stock Exchange, 1897–1914 (index, 1897 = 100).

Source: African Colonial Equities Database in combination with price data from fig. 1.

The data thus suggest that the company’s stock experienced two major speculative cycles of boom-and-bust: a particularly strong cycle from 1898 to 1905, and then a strong boom in 1909 followed by a longer period of decline.

After the end of the so-called Kaffir booms in South African mining shares in the 1880s and 1890s, noted in some previous literature, the index on total return on investments in South African mining barely decreased after the boom ended.Footnote 34 The collapse in Jungle shares, and the shares in Ashanti Goldfields in particular, were of a completely different magnitude: the collapse obliterated all of the economic gains investors had made during the boom. In contrast, the development for many other African ventures was stagnant during this period (with the possible exception of West African mining shares other than Ashanti Goldfields, which experienced a small boom in 1900 followed by a long decline). At issue in this article is to what extent these periods of boom-and-bust reflect Ashanti Goldfields’ real performance, and to what extent other aspects played a role in shaping the company’s share price. We now turn to the evidence from the financial press to study this in greater depth.

The First Boom-and-Bust Cycle in the Jungle, 1898–1905

Many of the early mining ventures in West Africa during the 1870s and 1880s were spectacular failures.Footnote 35 By the late 1890s, however, the London financial press started to publish reports on the positive prospects for mining in the region.Footnote 36 The Côte d’Or Company (predecessor of the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation) was briefly mentioned in the London financial press in 1897, but as the shareholders’ meeting was held privately, there was no information on which to report.Footnote 37 The first time that the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation appeared in the London financial press was at the end of 1898, and the reception was one of suspicion. On November 26, the Financial Times wrote:

Another mysterious company has come upon the market unannounced 𠈆namely, the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation, Limited—and yesterday the £1 shares were quoted as high as £14 on the rumour of rich discoveries. In view of the peculiar character of the undertaking, our readers would be well advised, we think, to stand clear.Footnote 38

Two days later, the same newspaper reported that the company in question was not included in the annual report from the Gold Coast colonial authorities on gold mining in the colony, noting, “This is hardly encouraging for those who are paying £14 for Ashanti Goldfields shares.”Footnote 39 The following day, on Tuesday, November 29, the Financial Times speculated over whether the price of the shares might be rigged by the company’s directors.Footnote 40 The Financial Times had managed to get an anonymous interview with a major shareholder, who, a week later, was reported as not being on the board of the company. In the interview, the anonymous shareholder described how the stock had been traded based on information spread among friends, first among the friends of the founders and then among their friends in turn.Footnote 41 Two days later, the company’s chairman, Frederick Gordon, in an interview with the Financial Times, vehemently denied the idea that the share price was rigged, claiming that none of the directors had sold any shares as one would expect if they simply had rigged the price:

Financial Times: So you regard the price as justified, as an anticipation of results?

FG: As an anticipation of the prospects being realised. […] But we have a very large extent of territory, and that there is gold there I am perfectly convinced.

FT: In large quantities?

FG: Yes, in large quantities.Footnote 42

By December 9, the Financial Times argued that the share price was perhaps not rigged, but there was a major speculative fever:

Sir Blundell Maple and Mr. Frederick Gordon are known to be successful men, and also to be enthusiastic about the prospects of the Ashanti Goldfields. This enthusiasm has spread to their friends, and the fever does not wane in its dissemination. These gentlemen are not anxious to part with their shares, more especially as they see the price gradually rising, and this only makes the friends’ friends more anxious to obtain a share in the good thing, and the price has thus gradually worked up until it has attained its present dazzling eminence.Footnote 43

This, cautioned the anonymous author in the Financial Times, was “a gamble out of which we see no possibility of their receiving an adequate return.”Footnote 44 The negative reporting seemingly had little effect on the company’s promoters. At the shareholders’ meeting in December 1898, Gordon was optimistic, claiming that the company owned “one of the finest mining properties in all probability in the world.”Footnote 45 The upbeat message could, however, not counter doubts on the market. In the following days, the shares would experience a “sensational collapse,” as the Financial Times would put it, arguing that the high price “has simply been the result of artificial conditions.”Footnote 46 The collapse soon recovered, however, and the price of a share was £9.5 at the end of 1898. The London financial press then lost interest in the company and did not report on it for several months.

It only started to take an interest again in summer 1900. The price of the company’s shares had increased, reaching £15.25 by the end of May 1900. In June 1900, the Financial Times reported that the uprising in Ashanti temporarily had stopped all mining operations, and that it would not be possible to resume them until the “disturbance” had been quelled by the colonial authorities.Footnote 47 Other developments around this time would cause somewhat of a rumble among the shareholders and in the financial press. In August 1900, The Economist published a piece highly critical of a new scheme, whereby another company, Ashanti Consols, was to be established to operate one of the Ashanti Goldfields mines. The owners of Ashanti Consols were, to a large extent, members of the board of Ashanti Goldfields, and the terms on which the former would take over the mine were highly favorable; the services rendered in exchange for this were “grotesquely inadequate,” according to the reporter.Footnote 48 In the following days, unnamed shareholders of Ashanti Goldfields would publicly protest against the scheme in the Letters column of the Financial Times. Footnote 49 Shares of the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation would, nonetheless, continue to increase in price, being traded for £18.75 at the end of August 1900.

By October 1900, reports in the financial press reported that trading in the equity of West African mining ventures had become so popular that a separate new section had been established on the London Stock Exchange, dubbed, with usual colonialist coloring, the Jungle.Footnote 50 The Financial Times cautioned against over-optimism in the new market: “This may mark the beginning of a boom, but it seems to me that the new West African market should have a placard stuck up over it, bearing the inscription, ‘The Stock Exchange is the way in, but where is the way out?’”Footnote 51 The newspaper’s position was seemingly based only on a general principle of precaution, as it published no substantial evidence on the matter. A few days later, it again argued that there was a “meagre basis of the Ashanti gamble,” but this time at least described what little was actually known about the sixty-plus mining ventures in the Gold Coast region.Footnote 52 The Mining Journal some weeks later commented that the West African market was “in the hands of riggers and manipulators,” but the writer was satisfied that attempts to start a boom on the market nonetheless “have not met with success.”Footnote 53 Newspapers’ reporting from the shareholders’ meeting of the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation was likewise highly skeptical of the company’s prospects, suggesting that “the speculative investor had better leave these inflated values for the professionals to play battledore and shuttlecock with among themselves.”Footnote 54 The negative reporting did little to dissuade potential investors, as the price of the share continued to increase for months, ending 1900 at £23.

By spring 1901, the equity had become so important that the company started to appear in the columns of the financial press summarizing the daily or weekly trading in mining shares on the London Stock Exchange. A careless reader of these columns could be excused for getting the idea that the price of the stock was fluctuating up and down throughout the spring, as small decreases in the price were reported with the same drastic headlines as large booms.Footnote 55 On net, however, the price of the share increased drastically throughout spring 1901, reaching the price of £31.75 in June 1901.

By this time, the company’s equity had become so valuable that the Investors’ Monthly Manual, a publication of The Economist, decided to include the company in its regular lists of stocks traded on the London Stock Exchange. The company was included in the IMM in June 1901, which is, incidentally, when its shares had peaked in price. In July 1901, the Mining Journal published an article titled the “West African Muddle,” which, in their opinion, was caused by the uncertain validity of mining concessions in the region.Footnote 56 By August 1901, The Economist reported that the Jungle department as a whole had experienced a pronounced set-back, with considerable losses for the leading shares.Footnote 57 For Ashanti Goldfields, this meant a drop in the share price from £31.75 to £28.5. The set-back was, however, a mere trifle of what investors in the company would experience in the coming months and years. In October 1901, the Financial Times reported, but without citing any source, that there was a fear among traders that several West African mining ventures might be the object of market manipulation by insiders.Footnote 58 A few days later, The Economist commented on the development: “The fact is that now the gambling fever has to some extent passed away, the public are beginning to realise upon how slight a basis the whole fabric of speculation has been raised, and to inquire what the intrinsic merits of the properties are.”Footnote 59 By this time, the company’s share had decreased in price, but was still traded at £26.

Ashanti Goldfields would to a large extent be dragged down on the London Stock Exchange by a number of other West African mining ventures, whether or not they were in different positions than Ashanti Goldfields. Some lone voices, such as an anonymous letter writer to the Financial Times, tried to point this out, arguing that while there was a large number of West African mining companies that were only “living on prospects,” some other companies—naming explicitly the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation—actually were undertaking serious mining operations at “great value.”Footnote 60 In the main, however, the reports in the financial press made quite sweeping statements about the development for Jungle equity in general, often (and especially in the headlines) with little distinction between individual companies. In the following months, the financial press kept reporting on prices for West African mining equity dropping more or less across the board.Footnote 61 When, for example, the managers of a competitor to Ashanti Goldfields declared publicly that the competitor’s concession essentially was worthless, the reporter for The Economist found “only too much reason to believe” that the same was the case for “most” West African mining ventures.Footnote 62 The Financial Times also reported that the colonial governor on the Gold Coast had cautioned that salting of mines had occurred in the colony, as if this was a widespread phenomenon.Footnote 63 This would, however, lead to letters protesting this claim from the directors of several companies operating in the region.Footnote 64

By early December 1901, The Economist reported that “West Africans continue to crumble.”Footnote 65 This was certainly true for Ashanti Goldfields as well, with the price of shares reaching only £20 by the end of the year, and by February 1902 it was down to £12.5. In March 1902 The Economist published a long article titled “The West African Market,” arguing that the kind of speculative boom-and-bust that had taken place in this section of the London Stock Exchange was rare. During this particular boom, share prices had been “rushed up to an utterly extravagant level,” and “large numbers of foolish people were induced to relieve some of the inside groups of large blocks of their holdings at very high prices.”Footnote 66

Throughout this crumbling of the Jungle, Ashanti Goldfields representatives defended what they claimed to be that company’s positive prospects. At the shareholders’ meeting in December 1901, for example, the chairman claimed that the company held a magnificent piece of property, and “nothing but patience was required for the proper development of their properties.”Footnote 67 Some months later, the company issued a circular—cited uncritically at length in the Financial Times—with many technical details on the ongoing operations, in which the chief engineer at the mines, John Daw, argued that “the future outlook is very satisfactory.”Footnote 68 The strategy worked for a time, as the fall in the price of the company’s equity came to a temporary halt by summer 1902, whereas many other Jungle ventures would continue to crumble for a while longer. By the end of the year, there were statements from company representatives reported in the financial press that Ashanti Goldfields soon would be able to pay dividends to the shareholders.Footnote 69 That the railway from the Gold Coast finally reached the company’s mines by the end of the year further increased optimism in the company’s prospects.Footnote 70 At the close of 1902, shares were at a price of £15.5, a substantial recovery from the depths just a half-year earlier.

This first boom-and-bust cycle can clearly be seen in the quantitative data. In figure 1, the price of the shares appreciated drastically during the first period of its existence (dotted line), starting at £2 per share in August 1898, and appreciating to £31.75 in June 1901. From June 1901, when the company’s equity started to be reported in the IMM to December 1902, the price of its shares was halved, around £15 by the end of 1902 (black line).

The stock market’s remaining optimism over the company’s prospects would not last very long. Colonial government reports, noted in the London press, certainly established that Ashanti Goldfields, in contrast to many other Jungle companies, actually had started mining operations in the region, and was exporting quite substantial amounts of gold.Footnote 71 This would not suffice for the investors; the price of the shares again dropped drastically around mid-1904, and would continue to do so for a whole year (see fig. 1).

Several factors might have contributed to this decline. By summer 1904, the London press had not reported on any major negative developments for the company’s actual performance. On the contrary, the only information available from these newspapers were reports on some positive developments, such as the installation of new machinery at the Ashanti Goldfields mine.Footnote 72

So what caused the drop in share prices? One triggering event seems to have been the death of both leading entrepreneurs behind the venture, Edwin Cade and Frederick Gordon. These events were reported in the press in March 1904, and might have caused some uncertainties about the company’s future management.Footnote 73 There were, however, other fundamental problems for the company. In December 1904, the London press reported on some problems that the company had had during the year with the crushing of ore at the mine. This information, however, reached the press only after it had been made publicly available via the company’s annual report in December 1904.Footnote 74 By this time, furthermore, there were rumors circulating that the estimates of the company’s ore reserves might be inflated. Consequently, an independent engineer, one Mr. Feldtmann, was appointed at the shareholders’ meeting to evaluate the matter.Footnote 75 Again, the financial press seems to have picked up on these rumors only after they were discussed at the shareholders’ meeting, so there were no notices in the press prior to the shareholders’ meeting. In May 1905, the London press could report that the rumors were true; the Financial Times noted an “amazing discrepancy” between the company engineer’s estimates and the independent engineer’s estimates, with the latter estimating the reserves to be only half of those of the former. The ore grades of these reserves were also lower than expected. Nevertheless, Feldtmann still argued that the company’s operation was a “sound mining venture,” but believed that further capital might be required to work the mines effectively.Footnote 76 The Mining Journal put a lot of trust in Feldtmann’s new estimates, as it commented that “the difficulties created by this state of things is not beyond remedy, and shareholders would be foolish, in our opinion, to throw away their shares at the present low quotation.”Footnote 77 Within a few days, the company declared that Daw had resigned, and he was replaced by Feldtmann.Footnote 78 At this time, the price of shares had reached a low point, with a split-adjusted price only marginally higher than the initial offering price when the company had launched several years before. The company’s first boom-and-bust cycle had reached its end.

A New Beginning and a Second Boom-and-Bust Cycle, 1905–1914

The new management of the company, including engineer Feldtmann, quickly drew up plans for how to operate the company’s mines, and let this be known via the financial press.Footnote 79 New capital was acquired through a debenture issued in July 1905,Footnote 80 and the new management devoted considerable time to developing the underground mining.Footnote 81 By September 1906, the London press could report on positive news, all based on the company’s own information, including that the newly developed underground sections of the mine exhibited good first assays, with much higher ore grade than previously anticipated.Footnote 82 The company’s annual report revealed substantial cost reductions, including in transportation costs as railway rates were reduced. Cyanide leeching had increased the amount of gold extracted from the ore.Footnote 83 The Mining Journal nonetheless cautioned against too great optimism, “since it appears that the improvement is mainly due to the Ashanti mine, which is practically dependent on a single shaft.”Footnote 84 By early 1907, new tests with roasting the ore before cyanide leeching further increased the amount of gold successfully extracted from the ore.Footnote 85 As these experiments were (in the company’s own words) a “complete success,” Ashanti Goldfields could finally declare its first dividend to the shareholders in April 1907.Footnote 86 The Financial Times drew the conclusion: “While, of course, there have been, and doubtless will continue to be, many disappointments amongst Jungle companies… recent events certainly appear to support the contention that the West African market has seen its worst days.”Footnote 87

In August 1907 the company announced new dividend payments to shareholders.Footnote 88 The following months were, however, not as positive, as Feldtmann decided that the ore output had to be reduced for a time, while new—and hopefully richer—ore bodies at the company’s Obuasi mine were opened up.Footnote 89 The price of the share reached its all-time nadir in April 1908, at a split-adjusted price of £1.375.

By summer 1908, the company reported that progress had been achieved, and at the shareholders’ meeting at the end of that year, the board reported that a new ore body, named Justice’s Find, had substantially improved the company’s known ore reserves. The chairman of the board during the meeting argued that “our position to-day is on a surer and more promising basis than it has been during the whole period of the corporation’s history.”Footnote 90 A few days later, the Financial Times reported that a supposedly independent mining expert, J. H Curle, just had visited the Gold Coast and was very optimistic about Ashanti Goldfields’ prospects, in particular because of the vast, but as yet unprospected, territories under its concession.Footnote 91 In early January 1909, the Mining Journal similarly published a report from an anonymous “special correspondent” on West African mining, including Ashanti Goldfields, stating that “a lot of good development is being accomplished” on Ashanti Goldfields’ concessions, and that the company had experienced “considerable success” in opening up new ore bodies.Footnote 92

These developments sparked a revival of interest in West African mining in general, and in Ashanti Goldfields shares in particular.Footnote 93 The supposedly enormous potential in the concession’s vast territory was repeated in some reporting in the London financial press.Footnote 94 The Financial Times published a caveat reminding readers of the boom-and-bust cycle that the company had experienced just some time ago, only to add that “it is contended by the supporters of the market that matters are on a more solid basis now.”Footnote 95 In February 1909, another supposedly independent mining expert, Frank Powell, testified that the company’s prospects were exceptionally good, stating: “In all my travels I have not come across a gold mine which holds out as good prospects as this one [the company’s Obuasi mine] does, in comparison with the market valuation of the concern.”Footnote 96

Several investors took such claims to heart because a new speculative wave started. Despite that the London financial press for several months published positive articles on the supposedly glorious prospects in the region in general, and for Ashanti Goldfields in particular, reporters seem to struggle to understand the renewed speculative fever. A report published in May 1909 provides one example of this:

No news transpired during business hours to account for the further big rise in Ashanti Goldfields, but it was surmised that some fresh development had occurred. Enthusiastic believers in the “Jungle,” however, argued that it was surprising that the shares had not previously responded to a greater extent to the recent important developments on the property. They suggested that it had apparently been overlooked by those not in close touch with things West African.Footnote 97

Throughout spring 1909, the London financial press continued to report, mostly uncritically, on how the price of shares increased in response to the company’s claims about positive developments at Obuasi.Footnote 98 The price of several Jungle shares were further increased on rumors first reported in May 1909, and confirmed in the following months, that some leading South African gold-mining houses had taken an interest in the Jungle market, and sent engineers to the Gold Coast to evaluate mining operations.Footnote 99 In July, the Mining Journal reported on a speech given by the governor of the Gold Coast at a dinner, wherein he had said that there certainly had been “a great deal of over-capitalisation and extravagance” in West African mines the past, but that the best mines in West Africa had survived the earlier boom-and-bust cycles.Footnote 100 The implicit message in the article was that such “extravagances” were a thing of the past, now that South African mining giants, with all their expertise, entered the market. By the end of July 1909, Ashanti Goldfields split-adjusted price had reached a new peak of £11.875, certainly lower than the peak during the first boom-and-bust cycle of the company’s shares, but still considerably higher than what it had been just a year earlier. In December 1909, The Economist summarized the history of the company thus far, arguing that all the positive development at Obuasi would lead one to expect that “the record of the new half decade should prove very different from that of its predecessor.”Footnote 101 Just a few weeks later, The Economist published at least some words of caution against a new Jungle fever, but at the same time offering assurances to the readers:

The rise from the lowest prices of 1909 to those now ruling has been little short of wonderful, especially in view of the airy nature of the foundations which support the fabric of the market. To gamble in West Africans is the fashion; to be out of it is for any professional speculator to admit he is behind the times… . The West African market has been accorded a boom which threatens to put into the shade the wild gamble of eight and a-half years ago, when conditions on the Gold Coast were very different from what they are to-day. Now, we have a certain amount of information about gold mining in the Jungle; then, ignorance abetted rumour, and the two hoisted prices to heights of absurdity.Footnote 102

Little did The Economist’s reporters know that the following half-decade indeed would be different for the company, but perhaps not as they had expected: the speculative boom of 1909 was already over, and the price of the shares would start to fall yet again (see fig. 1). The following years, until the outbreak of the World War I in 1914, would seem rather uneventful for Ashanti Goldfields, judging from the reporting in the London financial press. Reporting was generally positive to the company’s prospects, to the extent that they were even reported. Even though known ore reserves were decreasing, output grew substantially, and labor costs were kept low.Footnote 103 The only direct critique of the board is in reference to the level of reimbursements to the members of the board themselves, an issue that was defended when several claimed to be founders of the company, and therefore ought to be compensated for all their hard work.Footnote 104 Nonetheless, the price of the shares continued to fall. This struck some observers as most strange. As one letter writer to the Financial Times, under the pseudonym Monte Cristo, argued in March 1911, despite the company having what the correspondent believed was a sound business, and producing more than three times as much output as just some years earlier, the price of the shares were still lower than at that time.Footnote 105

Sources for the Financial Press

As noted in the previous discussion, the financial press often lacked access to independent sources for their reporting on the development of Ashanti Goldfields. This is revealed quantitatively in figure 3, which shows the total media coverage that the company received during the period under study. To gather our date, we searched indices for the term “Ashanti Goldfields” appearing anywhere in the text. Articles referring to other companies with similar names have been excluded manually.

Figure 3 Media coverage of the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation, 1895–1914, by type of source, N = 2,143

Sources: Online archives of the Financial Times and The Economist, accessed December 17, 2019.

Note: Reporting in the Mining Journal is not included because the journal’s index includes only major articles, not shorter references to the company under other headlines. The articles from the indices do not suggest that coverage differed substantially.

As seen figure 3, the vast majority, 72 percent, of all media coverage that the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation received in two newspapers—the Financial Times and The Economist—during this period was on stock market activity; for example, the amount of trading in a stock and whether the price of shares was increasing or decreasing. This reporting occasionally included some brief discussion as to why share prices moved in a certain direction, often in reference to other reporting in the same newspaper, but as a rule it contained little information as to the fundamentals of the company’s performance. A substantial share of all coverage on fundamental information about Ashanti Goldfields, 22 percent of the total media coverage on the company, was information that the company itself provided. This category includes shorter pieces; for example, announcements of dividends to be paid or the amount of ore processed during the previous month. It also includes longer articles summarizing the main contents of the company’s annual reports, or accounts of the proceedings of annual general meetings of the shareholders, as well as advertisements from the company. A small fraction of the media coverage, 2 percent, were editorials or comments by the newspapers’ editorial teams, in general responding to some other news about the company. Letters to the editor also account for a small fraction of all media coverage on the company, again at 2 percent. This includes both anonymous and identified authors, in the latter case in several instances identified as shareholders in the company. How well informed and independent these letter writers were about the operations of the company is in many cases hard to tell. Only a tiny fraction of the media coverage, around 1 percent, was based on sources that were clearly independent from the company, including articles based on reports from the colonial government and from special correspondents (anonymous or identified), and interviews with independent sources (e.g., independent mining engineers). An investor in Ashanti Goldfields would thus not be much better informed about the fundamentals of the company from reading the financial press than if he or she simply accessed the information provided to shareholders in the form of the company’s annual reports or at the shareholders’ meetings.

Conclusion

We have in this article contributed to an understanding of the role that media plays during a speculative financial bubble. We employed a qualitative case study on the so-called Jungle bubbles in West African mining stocks in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This African case was selected because it is a critical example of a peripheral, emerging market and allowed us to study how the financial press struggled to deal with asymmetric information in such a context. Ashanti Goldfields Corporation was the center of our research as it was the largest of the Jungle companies. We studied the company’s performance from the perspective of the investor; that is, what an investor could earn from investing in the company, and how this related to speculative bubbles.

As other scholars have argued, London’s informational position was one reason London could establish its position as the most important hub of the global financial network around 1900. Nevertheless, making relevant information available was a struggle for the City’s financial press, particularly when it came to peripheral markets. For Ashanti Goldfields, the financial press had limited access to reliable sources of information on the company’s activities. West Africa was geographically quite distant, so the London press had few local correspondents in the region. Thus, only a tiny share of the media coverage on Ashanti Goldfields was based on sources that could be argued to be independent from the company. On the few occasions when independent sources reported on the company’s performance—for example when colonial governments issued reports on the mining industry, or when independent mining engineers visited the region—the financial press was quick to publish what information they could gain. As a rule, however, such independent sources of information were scarce. The financial press had little information on Ashanti Goldfields other than what company managers provided. Undoubtedly, this allowed several insiders to profit during speculative cycles, as noted in the press when considering the development in hindsight.

At their best, newspaper articles based on the company’s own reports or statements were accompanied by critical editorial comment. Even so, such comments were often based either on general principles of precaution or on generalizations about all companies operating in the Jungle, rather than on concrete evidence regarding Ashanti Goldfields in particular. The financial press was, furthermore, often slow in picking up on information related to the company. During the crucial crumble of the Jungle in 1904, for example, several investors appear much better informed than the financial press about problems with the company’s estimated ore reserves. The financial press could only report on the underlying nature of these problems after most of the event was over.

A lack of information about fundamentals of Ashanti Goldfields did not, however, stop the financial press from reporting on how the company’s shares were doing on the London Stock Exchange. The vast majority of the media coverage during the period under study was of this kind. Such reporting appeared under drastic headlines, both when the company’s stock price was booming and when it went bust. Such stories served to spread an interest in the company (when it was booming) or scare investors away (when stock prices tumbled). The frequent reporting on booms and busts in daily or weekly summaries of the trade in stocks on the London Stock Exchange had the same effect. Media coverage was, to a significant level, driven by the market price of the company, not by company fundamentals. In this way, the financial press mirrored and potentially reinforced the speculative bubble in the Jungle.