Introduction

Meta-analytic evidence suggests that childhood trauma (i.e. potentially harmful experiences as sexual, physical and emotional abuse as well as physical and emotional neglect; Morgan and Fisher, Reference Morgan and Fisher2007) increases transition risk in individuals at ultra-high-risk state for psychosis (UHR; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer, Read, van Os and Bentall2012). Childhood trauma is associated with the persistence of psychotic symptoms in subclinical and clinical samples (Trotta et al., Reference Trotta, Murray and Fisher2015; van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, van Nierop, Viechtbauer, Velthorst, van Winkel, Genetic, Bruggeman, Cahn, de Haan, Kahn, Meijer, Myin-Germeys, van Os and Wiersma2015; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Alvarez-Jimenez, Garcia-Sanchez, Hulbert, Barlow and Bendall2018). A UHR state is commonly based on three criteria (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Schultze-Lutter, Bonoldi, Borgwardt, Riecher-Rössler, Addington, Perkins, Woods, McGlashan, Lee, Klosterkötter, Yung and McGuire2015a; Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Borgwardt, Woods, Addington, Nelson, Nieman, Stahl, Rutigliano, Riecher-Rössler, Simon, Mizuno, Lee, Kwon, Lam, Perez, Keri, Amminger, Metzler, Kawohl, Rössler, Lee, Labad, Ziermans, An, Liu, Woodberry, Braham, Corcoran, McGorry, Yung and McGuire2016): attenuated psychotic symptoms, brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms and genetic risk and deterioration syndrome. Within 2 years, 20% of UHR individuals have been reported to transition to psychosis (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Cappucciati, Borgwardt, Woods, Addington, Nelson, Nieman, Stahl, Rutigliano, Riecher-Rössler, Simon, Mizuno, Lee, Kwon, Lam, Perez, Keri, Amminger, Metzler, Kawohl, Rössler, Lee, Labad, Ziermans, An, Liu, Woodberry, Braham, Corcoran, McGorry, Yung and McGuire2016) and a considerable proportion experience comorbid anxiety or depression (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Nelson, Valmaggia, Yung and McGuire2014). However, in recent years, declining transition rates have been reported and various reasons for this have been discussed (e.g. different clinical profiles, earlier referrals, more effective treatment; Yung et al., Reference Yung, Yuen, Berger, Francey, Hung, Nelson, Phillips and McGorry2007; Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Yuen, McGorry, Yung, Lin, Wood, Lavoie and Nelson2016; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Yuen, Lin, Wood, McGorry, Hartmann and Yung2016; Formica et al., Reference Formica, Phillips, Hartmann, Yung, Wood, Lin, Amminger, McGorry and Nelson2020). Meta-analyses show that the majority of UHR individuals who do not transition to psychosis do not remit from UHR status within 2 years either, and show marked impairments in functioning (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Borgwardt, Riecher-Rössler, Velthorst, de Haan and Fusar-Poli2013; Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Rocchetti, Sardella, Avila, Brandizzi, Caverzasi, Politi, Ruhrmann and McGuire2015b). UHR individuals’ functional level is comparable to that reported in patients with social phobia or major depressive disorder, and closer to that observed in psychosis patients than in healthy controls (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Rocchetti, Sardella, Avila, Brandizzi, Caverzasi, Politi, Ruhrmann and McGuire2015b). Hence, the persistence of symptoms and functioning are important outcomes.

Although it is well accepted that childhood trauma is associated with clinical outcomes, psychological mechanisms involved remain largely unclear. Current models of psychosis suggest that childhood trauma amplifies stress reactivity, comprising increased negative affect, decreased positive affect and increased psychotic experiences in response to minor daily stressors (Hammen et al., Reference Hammen, Henry and Daley2000; Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Kuhn and Prescott2004; Myin-Germeys and van Os, Reference Myin-Germeys and van Os2007; Collip et al., Reference Collip, Myin-Germeys and Van Os2008; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Charalambides, Hutchinson and Murray2010; Howes and Murray, Reference Howes and Murray2014). Stress reactivity is thought to be a behavioural marker of stress sensitisation as a candidate mechanism underlying the association between childhood trauma and psychosis (Hammen et al., Reference Hammen, Henry and Daley2000; Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, van Os, Schwartz, Stone and Delespaul2001; Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Kuhn and Prescott2004; Wichers et al., Reference Wichers, Schrijvers, Geschwind, Jacobs, Myin-Germeys, Thiery, Derom, Sabbe, Peeters and Delespaul2009; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Charalambides, Hutchinson and Murray2010, Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan, Boydell, Kirkbride, Doody and Jones2014; Bentall et al., Reference Bentall, de Sousa, Varese, Wickham, Sitko, Haarmans and Read2014; Howes and Murray, Reference Howes and Murray2014). There is evidence that stress reactivity in daily life is elevated in patients with psychosis, individuals with familial risk for psychosis, subclinical psychosis phenotypes and UHR individuals (Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, van Os, Schwartz, Stone and Delespaul2001, Reference Myin-Germeys, Peeters, Havermans, Nicolson, DeVries, Delespaul and Van Os2003; Lataster et al., Reference Lataster, Wichers, Jacobs, Mengelers, Derom, Thiery, Van Os and Myin-Germeys2009; Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Kempton, Valmaggia, Craig, Garety, Onyejiaka, Gayer-Anderson, So, Hubbard, Beards, Dazzan, Pariante, Mondelli, Fisher, Mills, Viechtbauer, McGuire, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016b; van der Steen et al., Reference van der Steen, Gimpel-Drees, Lataster, Viechtbauer, Simons, Lardinois, Michel, Janssen, Bechdolf and Wagner2017). Stress reactivity, measured with self-report questionnaires, has also been found to be associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with first-episode psychosis (Conus et al., Reference Conus, Cotton, Schimmelmann, McGorry and Lambert2009). Furthermore, in adolescent service users, childhood trauma was associated with increased emotional and psychotic stress reactivity for individuals, who reported high v. low levels of trauma (Rauschenberg et al., Reference Rauschenberg, van Os, Cremers, Goedhart, Schieveld and Reininghaus2017). This is consistent with other experience sampling studies showing elevated stress reactivity in patients of general practitioners, UHR individuals and in patients with psychosis, who have experienced childhood trauma (Glaser et al., Reference Glaser, Van Os, Portegijs and Myin-Germeys2006; Lardinois et al., Reference Lardinois, Lataster, Mengelers, Van Os and Myin-Germeys2011; Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Gayer-Anderson, Valmaggia, Kempton, Calem, Onyejiaka, Hubbard, Dazzan, Beards, Fisher, Mills, McGuire, Craig, Garety, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016a). Taken together, these findings suggest effect modification of stress reactivity by childhood trauma or, in other words, synergistic effects of trauma and stress reactivity, in those at-risk or with psychotic disorder (i.e. an interaction or synergistic model).

Furthermore, other possibilities of how childhood trauma and stress reactivity may combine with each other may be relevant (Schwartz and Susser, Reference Schwartz, Susser, Schwartz, Susser, Morabia and Bromet2006; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan, Boydell, Kirkbride, Doody and Jones2014). Stress reactivity may take on the role of a mediator, such that childhood trauma may impact outcomes indirectly, via pathways through stress reactivity (i.e. a mediation model). In line with this, there is evidence from cross-sectional studies using self-report questionnaires in community samples that exposure to trauma in childhood may be linked to subclinical psychotic symptoms via stress reactivity (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Anglin, Klugman, Reeves, Fineberg, Maxwell, Kerns and Ellman2014; Rössler et al., Reference Rössler, Ajdacic-Gross, Rodgers, Haker and Müller2016). To increase complexity further, childhood trauma may both modify stress reactivity and connect with this putative mechanism along a causal pathway via mediation (Hafeman, Reference Hafeman2008; Hafeman and Schwartz, Reference Hafeman and Schwartz2009). In other words, exposure to trauma may interact with, and be predictive of, stress reactivity in pathways to psychosis (i.e. a mediated synergy model). To our knowledge, only one study to date has investigated both effect modification and mediation in the same analyses in relation to psychosis, suggesting that childhood and adult disadvantage may combine in complex ways (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan, Boydell, Kirkbride, Doody and Jones2014). Although stress reactivity may be an important putative risk mechanism, no study to date has investigated whether stress reactivity in UHR individuals’ daily life is greater in those exposed to high levels of childhood trauma, as well as its predictive value for clinical outcomes (Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Gayer-Anderson, Valmaggia, Kempton, Calem, Onyejiaka, Hubbard, Dazzan, Beards, Fisher, Mills, McGuire, Craig, Garety, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016a, Reference Reininghaus, Kempton, Valmaggia, Craig, Garety, Onyejiaka, Gayer-Anderson, So, Hubbard, Beards, Dazzan, Pariante, Mondelli, Fisher, Mills, Viechtbauer, McGuire, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016b). Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate the interplay of exposure to childhood trauma and stress reactivity as a candidate mechanism in predicting clinical outcomes in UHR individuals at 1- and 2-year follow-up using experience sampling data. We tested, in light of the theoretical models outlined above, the following hypotheses (see online Supplementary Fig. S1):

(H1) An increase in momentary stress is associated with increased negative affect, decreased positive affect and increased psychotic experiences.

(H2) The magnitude of associations between momentary stress and negative affect, positive affect and psychotic experiences is modified by childhood trauma, such that these associations are greater in individuals exposed to high v. low levels of childhood trauma (i.e. an effect modification or interaction model).

(H3) Stress reactivity (measured at baseline) predicts illness severity, functioning and symptom burden at 1- and 2-year follow-up.

(H4) Childhood trauma (measured at baseline) predicts illness severity, functioning and symptom burden at 1- and 2-year follow-up. The effects of childhood trauma will be mediated via pathways through stress reactivity (i.e. a mediation model).

In exploratory analyses, we further aimed to investigate whether (i) the magnitude of associations between momentary stress and negative affect, positive affect and psychotic experiences is modified by transition status, and (ii) the effect of childhood trauma on transition status will be mediated via pathways through stress reactivity (i.e. a mediation model).

Methods

Sample

The sample comprises UHR individuals from London (UK), Melbourne (Australia) and Amsterdam/The Hague (the Netherlands) recruited as part of the EU-GEI High Risk Study (European Network of National Networks studying Gene–Environment Interactions in Schizophrenia, 2014), a naturalistic prospective multicentre study that aimed to identify the interactive genetic, clinical and environmental determinants of schizophrenia. For the UK, participants were recruited from Outreach and Support in South London (OASIS), a clinical service for UHR individuals provided by the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Byrne, Badger, Valmaggia and McGuire2013), the West London Mental Health NHS Trust (WLMHT), and a community survey of General Practitioner practices (Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Gayer-Anderson, Valmaggia, Kempton, Calem, Onyejiaka, Hubbard, Dazzan, Beards, Fisher, Mills, McGuire, Craig, Garety, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016a). In Melbourne, participants were recruited from the Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation (PACE) clinic, a clinical arm of Orygen Youth Health, whose catchment area includes the north-western metropolitan region of Melbourne. Dutch participants were recruited from the Early Detection for Psychosis clinics of Parnassia, The Hague, and Amsterdam UMC. All centres provide assessments and specialised clinical services for people with UHR.

UHR individuals, aged 15–35 years, were eligible to participate if they met at least one of the UHR criteria as defined by the Comprehensive Assessment of At Risk Mental State (CAARMS; Yung et al., Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Phillips, Kelly, Dell'Olio, Francey, Cosgrave, Killackey and Stanford2005): (1) attenuated psychotic symptoms: the presence of subthreshold positive psychotic symptoms for at least 1 month during the past year, (2) brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms: an episode of frank psychotic symptoms that have resolved in less than 1 week without receiving treatment and (3) vulnerability: a first-degree relative with a psychotic disorder or diagnosed with schizotypal personality disorder in combination with a significant drop in functioning or chronic low functioning during at least 1 month in the previous year. Exclusion criteria were: (1) the presence of a current or past psychotic disorder, (2) symptoms relevant for inclusion are explained by a medical disorder or drugs/alcohol dependency and (3) IQ < 60.

Data collection

Experience sampling method (ESM) measures

Momentary stress, affect and psychotic experiences were assessed using the ESM (Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, van Os, Schwartz, Stone and Delespaul2001; Palmier-Claus et al., Reference Palmier-Claus, Dunn and Lewis2012), a structured diary method with high ecological validity, in which subjects are asked to report their thoughts, feelings and symptoms in daily life (Shiffman et al., Reference Shiffman, Stone and Hufford2008; Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, Oorschot, Collip, Lataster, Delespaul and van Os2009; Palmier-Claus et al., Reference Palmier-Claus, Myin-Germeys, Barkus, Bentley, Udachina, Delespaul, Lewis and Dunn2011). At baseline, participants used a dedicated digital device for data collection (the Psymate®, www.psymate.eu/). The target constructs (i.e. stress, affect and psychotic experiences) show high and continuous variation over time. To obtain a representative sample of participants’ experiences in daily life and to capture relevant variation in these target constructs with high resolution, a time-contingent sampling design with a blocked random schedule and a high-sampling frequency was used for ESM data collection, i.e. ten times a day for six consecutive days at random moments within set blocks of time (Shiffman et al., Reference Shiffman, Stone and Hufford2008; Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, Kasanova, Vaessen, Vachon, Kirtley, Viechtbauer and Reininghaus2018). In line with previous literature, data were included if ⩾20 valid responses were provided over the assessment period (Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, van Os, Schwartz, Stone and Delespaul2001, Reference Myin-Germeys, Delespaul and Van Os2005; Delespaul et al., Reference Delespaul, deVries and van Os2002; Corcoran et al., Reference Corcoran, Cummins, Rowse, Moore, Blackwood, Howard, Kinderman and Bentall2006; Bentall et al., Reference Bentall, Rouse, Kinderman, Blackwood, Howard, Moore, Cummins and Corcoran2008, Reference Bentall, Rowse, Shryane, Kinderman, Howard, Blackwood, Moore and Corcoran2009; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Dunn, Fowler, Bebbington, Kuipers, Emsley, Jolley and Garety2013; Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Kempton, Valmaggia, Craig, Garety, Onyejiaka, Gayer-Anderson, So, Hubbard, Beards, Dazzan, Pariante, Mondelli, Fisher, Mills, Viechtbauer, McGuire, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016b). A detailed description of the ESM procedure and measures is provided in online Supplementary material 2.

Childhood trauma

Childhood trauma was assessed using the short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), an established 25-item self-report measure enquiring about traumatic experiences during childhood (for detailed information see online Supplementary material 2; Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge and Handelsman1997, Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge, Ahluvalia, Stokes, Handelsman, Medrano and Desmond2003; Bernstein and Fink, Reference Bernstein and Fink1998; Scher et al., Reference Scher, Stein, Asmundson, McCreary and Forde2001; Wingenfeld et al., Reference Wingenfeld, Spitzer, Mensebach, Grabe, Hill, Gast, Schlosser, Hopp, Beblo and Driessen2010).

Clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes were assessed at baseline, 1- and 2-year follow-up. As the time points for follow-up assessments varied, the data closest to 1 and 2 years after baseline were selected as follow-up data. Illness severity was assessed using the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI; Guy, Reference Guy1976). The level of functioning was assessed using the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF; American Psychiatric Association, 2002). Symptoms were assessed using the unusual thought content, perceptual abnormalities, anxiety and tolerance to normal stress subscales of the CAARMS (Yung et al., Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Phillips, Kelly, Dell'Olio, Francey, Cosgrave, Killackey and Stanford2005). To ensure data quality, extensive training was provided (see online Supplementary material 3).

Statistical analysis

As ESM data have a multilevel structure with multiple observations (level-1) nested within participants (level-2), the ‘mixed’ command in Stata 15 was used to fit two-level, linear mixed models (StataCorp, 2017). Continuous variables of momentary stress, affect, psychotic experiences and childhood trauma were z-standardised for interpreting significant interaction terms. First, we included the composite stress measure as an independent variable and negative affect, positive affect and psychotic experiences as outcome variables (H1). Second, we added two-way interaction terms for stress × childhood trauma to examine whether the associations between momentary stress, negative affect, positive affect and psychotic experiences were modified by childhood trauma (H2). The hypothesis that the associations of momentary stress with affect and psychotic experiences were greater in individuals exposed to high v. low levels of childhood trauma (±1 s.d. of standardised CTQ scores, mean = 0, s.d. = 1) was tested by using the ‘testparm’ command for computing Wald tests to assess statistical significance of two-way interaction terms and the ‘lincom’ command to compute linear combinations of coefficients (Aiken and West, Reference Aiken and West1991; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2003). Third, we used the ‘predict’ option to obtain fitted values of psychotic experiences and affect predicted by the composite stress measure. We used linear regression analysis to investigate whether these fitted values representing stress reactivity predicted illness severity, level of functioning and symptom burden at follow-up, while controlling for baseline values (H3). Finally, we performed mediation analysis using the ‘gsem’ command to investigate whether the effects of childhood trauma on illness severity, level of functioning and symptom burden were mediated by stress reactivity (H4). The total effect of childhood trauma on clinical outcomes was apportioned into a direct effect and an indirect effect through stress reactivity. The indirect effect was computed using the product of coefficients strategy. The indirect and the total effect were computed and tested on significance using the ‘nlcom’ command.

Restricted maximum-likelihood (H1 and H2) or maximum-likelihood estimation (H3 and H4) were applied, allowing for the use of all available data under the relatively unrestrictive assumption that data are missing at random and if all variables associated with missing values are included in the model (Little and Rubin, Reference Little and Rubin1987; Mallinckrodt et al., Reference Mallinckrodt, Clark and David2001). Following previous studies (Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Gayer-Anderson, Valmaggia, Kempton, Calem, Onyejiaka, Hubbard, Dazzan, Beards, Fisher, Mills, McGuire, Craig, Garety, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016a, Reference Reininghaus, Kempton, Valmaggia, Craig, Garety, Onyejiaka, Gayer-Anderson, So, Hubbard, Beards, Dazzan, Pariante, Mondelli, Fisher, Mills, Viechtbauer, McGuire, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016b; Rauschenberg et al., Reference Rauschenberg, van Os, Cremers, Goedhart, Schieveld and Reininghaus2017; Hermans et al., Reference Hermans, Myin-Germeys, Gayer-Anderson, Kempton, Valmaggia, McGuire, Murray, Garety, Wykes, Morgan, Kasanova and Reininghaus2020), all analyses were adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity and centre as these are known as a priori confounders (based on evidence on the basic epidemiology of psychosis). To control for confounding of findings by comorbid disorders, all analyses were controlled for comorbid major depressive and anxiety disorders. In addition, analyses for testing H3 and H4 were controlled for time to follow-up to account for variation in time to follow-up. Unadjusted analyses and sensitivity analyses in a restricted sample assessed in a ±6 month time interval around the expected follow-up time points are displayed in online Supplementary materials 4–6.

Results

Basic sample and clinical characteristics

A total of 108 participants were assessed with the ESM during the study period. Of these, 79 participants completed ESM assessment with ⩾20 valid responses (i.e. 73.1% of 108; valid responses: M = 38, range 20–57). Assessment of clinical outcomes was completed for 48 participants at 1-year follow-up (61% of the full sample; months away from optimal 1-year follow-up time point: median = 0.5, range −8.7 to 4.6) and 36 participants at 2-year follow-up (46% of the full sample; months away from optimal 2-year follow-up time point: median = 0.5, range −5.6 to 22.6). Nine individuals (11%) transitioned to psychosis by the final follow-up time point. Participants were on average 23 years old (s.d. = 4.93) and 56% were women. The majority (67%) of the sample was white, followed by 15% with black ethnicity. Seventy-six percent of the participants were diagnosed with a comorbid axis I disorder. Comparing the current study's participants to individuals included in the EU GEI High-Risk study, for whom ESM data were not collected (N = 266), there were no differences in demographics (age: t = −1.33, p = 0.185; gender: χ 2 = 3.58, p = 0.059; ethnicity: χ 2 = 6.53, p = 0.258) or overall prevalence of comorbid disorders (χ 2 = 1.82, p = 0.177). However, the current sample showed higher levels of childhood trauma (t = −2.59, p = 0.010), a higher prevalence of specific phobias (χ 2 = 4.86, p = 0.027) and a lower prevalence of major depressive disorder (χ 2 = 4.67, p = 0.031) compared to participants, for whom ESM data were not collected (see Table 1).

Table 1. Basic sample and clinical characteristics

Note. ESM, experience sampling method; N, sample size, s.d., standard deviation. Comorbidity: participants were diagnosed with a comorbid disorder, if classification criteria were fulfilled. Thus, one participant can be diagnosed with multiple comorbid disorders.

Association between momentary stress, affect and psychotic experiences (H1)

Momentary stress was associated with small to moderate increases in negative affect (β = 0.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.27 to 0.36, p < 0.001) and psychotic experiences (β = 0.16, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.20, p < 0.001) as well as with a moderate decrease in positive affect (β = −0.38, 95% CI −0.43 to −0.34, p < 0.001).

Association between momentary stress, affect and psychotic experiences by childhood trauma (H2)

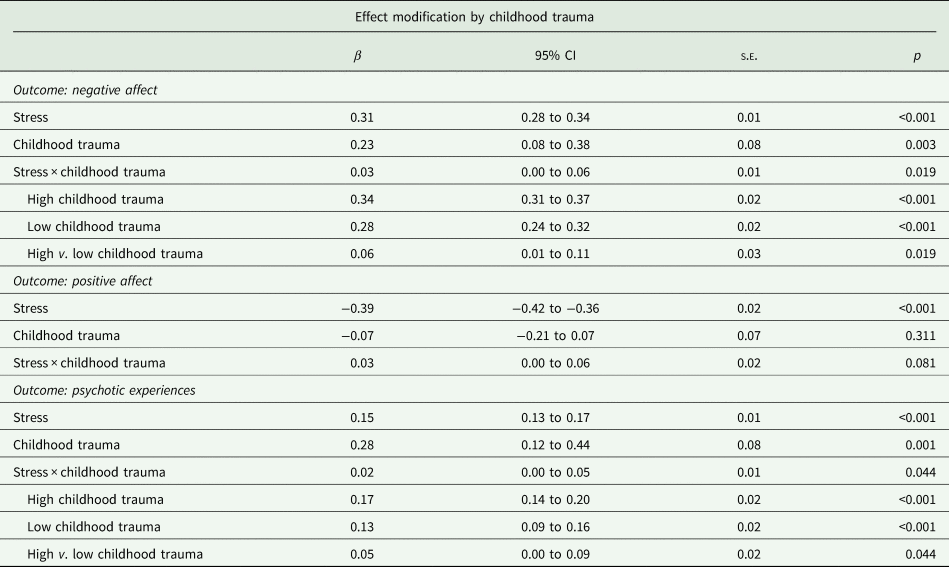

Childhood trauma modified the associations of momentary stress with negative affect (stress × childhood trauma: β = 0.03, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.06, p = 0.019) and psychotic experiences (stress × childhood trauma: β = 0.02, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.05, p = 0.044, see Table 2). These associations were greater in individuals with higher levels of childhood trauma (outcome negative affect: high v. low childhood trauma: β = 0.06, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.11, p = 0.019; outcome psychotic experiences: high v. low childhood trauma: β = 0.05, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.09, p = 0.044). Furthermore, we found a non-significant indication that childhood trauma modified the association between momentary stress and positive affect (stress × childhood trauma: β = 0.03, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.06, p = 0.081).

Table 2. Modification of the association between momentary stress and affect/psychotic experiences by childhood trauma

Note: Results adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, centre, comorbid major depressive and anxiety disorders. Childhood trauma assessed with the CTQ. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval, s.e., standard error.

Stress reactivity and clinical outcomes at follow-up (H3)

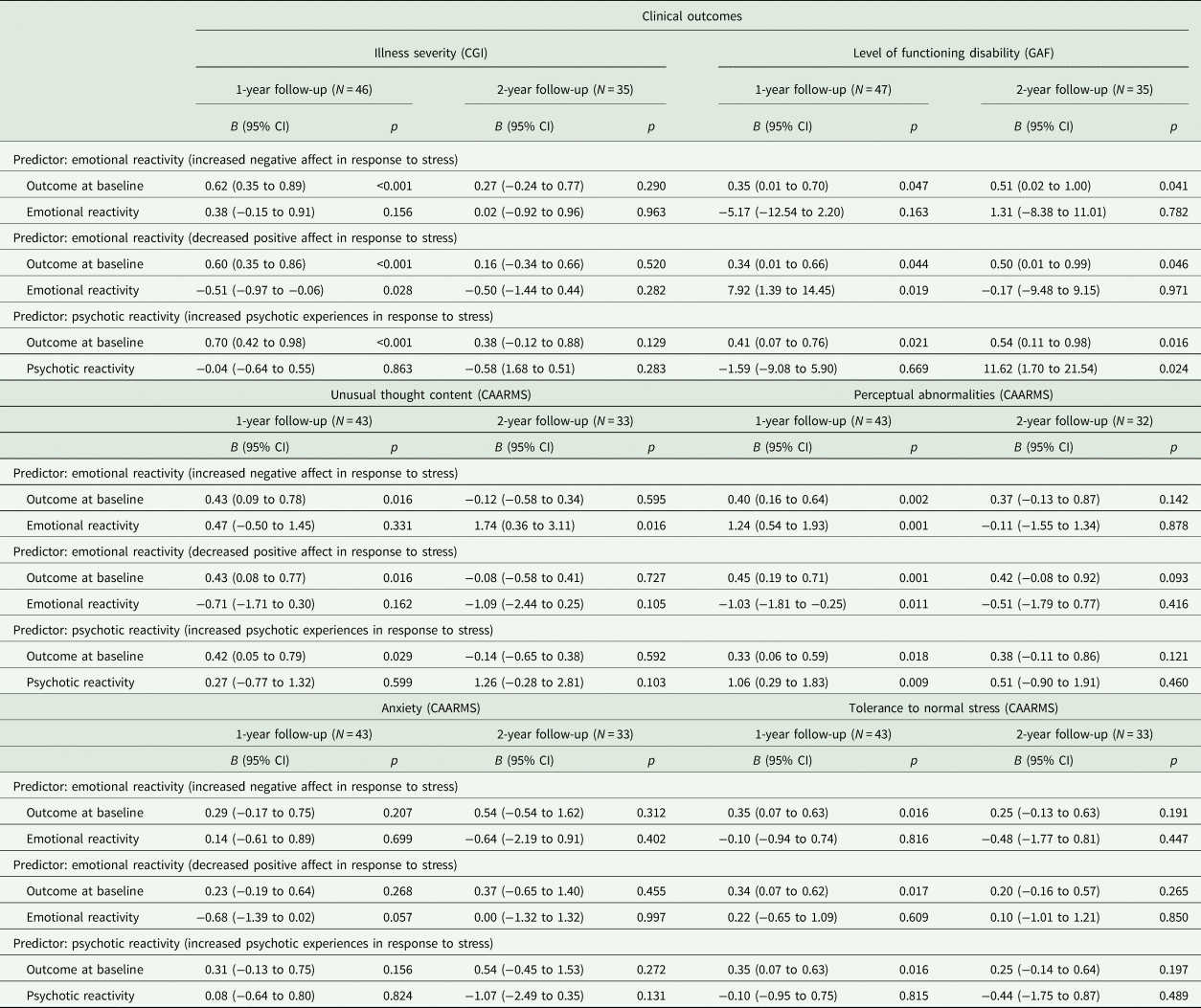

Decreased positive affect in response to stress was associated with higher illness severity (B = −0.51, 95% CI −0.97 to −0.06, p = 0.028) and lower level of functioning (B = 7.92, 95% CI 1.39 to 14.45, p = 0.019) at 1-year follow-up (see Table 3). In addition, the level of functioning at 2-year follow-up was predicted by psychotic stress reactivity (B = 11.62, 95% CI 1.70 to 21.54, p = 0.024).Footnote 1 Increased negative affect in response to stress predicted unusual thought content at 2-year follow-up (B = 1.74, 95% CI 0.36 to 3.11, p = 0.016). Moreover, perceptual abnormalities at 1-year follow-up were predicted by emotional (negative affect: B = 1.24, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.93, p = 0.001; positive affect: B = −1.03, 95% CI −1.81 to −0.25, p = 0.011) and psychotic stress reactivity (B = 1.06, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.83, p = 0.009). There was no evidence that emotional or psychotic stress reactivity predicted anxiety or tolerance to normal stress.

Table 3. Clinical outcomes at 1- and 2-year follow-up predicted by emotional and psychotic stress reactivity at baseline and clinical outcome at baseline

Note: Results adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, centre, comorbid major depressive and anxiety disorders and time to follow-up. Illness severity assessed with the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI). Level of functioning assessed with the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF). N, sample size; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Emotional and psychotic stress reactivity as mediators of the association between childhood trauma and clinical outcomes (H4)

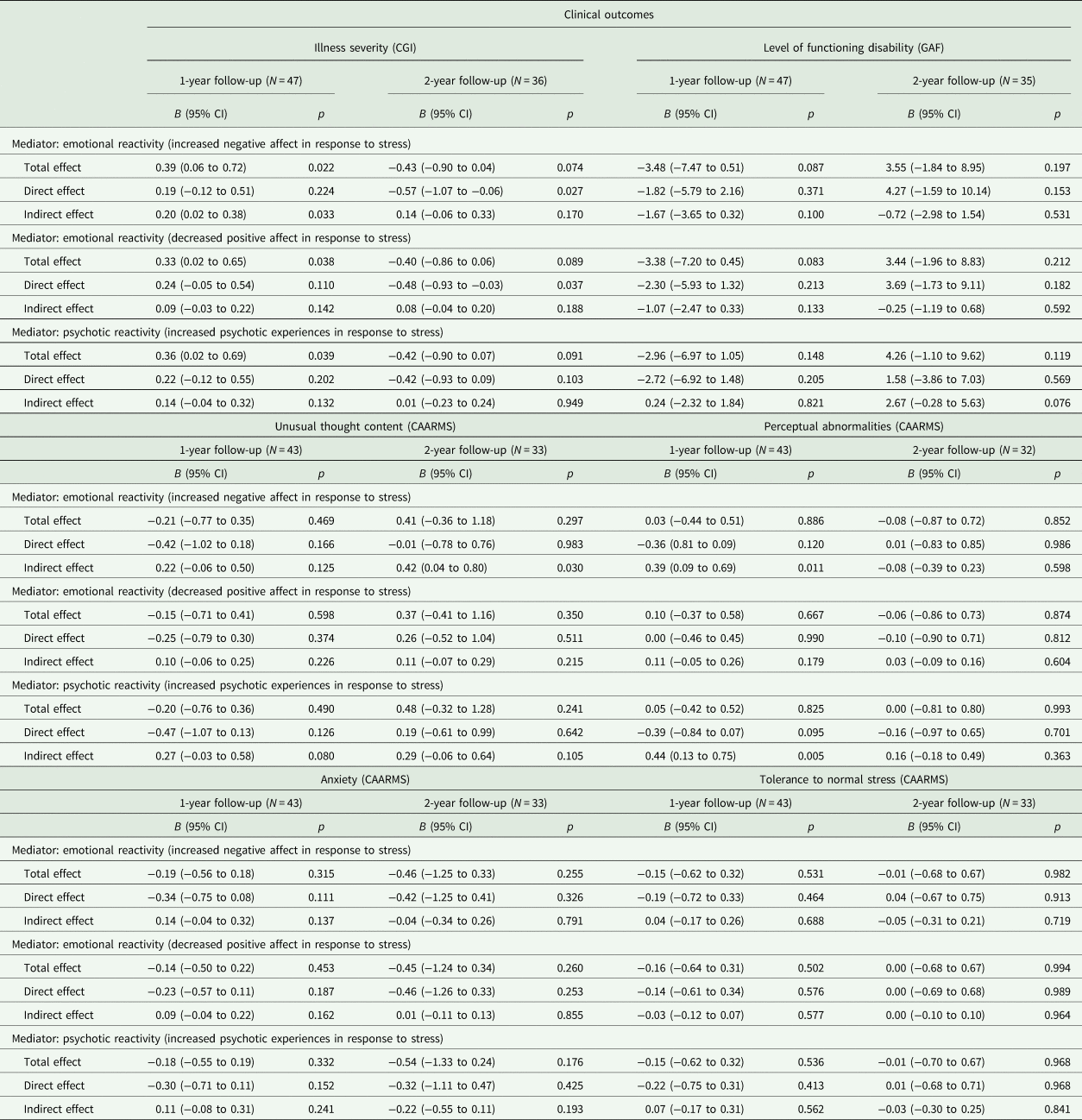

Table 4 shows findings on total, direct and indirect effects of childhood trauma and stress reactivity on clinical outcomes at follow-up. Increased negative affect in response to stress mediated the association of childhood trauma and illness severity at 1-year follow-up (indirect effect: B = 0.20, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.38, p = 0.033). We found no evidence that emotional and psychotic stress reactivity mediated the association of childhood trauma and level of functioning. The association of childhood trauma and unusual thought content at 2-year follow-up was mediated by increased negative affect in response to stress (B = 0.42, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.80, p = 0.030). In addition, the association of childhood trauma and perceptual abnormalities at 1-year follow-up was mediated by increased negative affect (indirect effect: B = 0.39, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.69, p = 0.011) and psychotic experiences in response to stress (indirect effect: B = 0.44, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.75, p = 0.005). High levels of childhood trauma were associated with more intense reactivity in the form of a stronger increase of negative affect and psychotic experiences in response to stress, which, in turn, was associated with higher illness severity, unusual thought content and perceptual abnormalities at follow-up. We found no evidence for direct effects of childhood trauma on anxiety and tolerance to normal stress and no mediation via stress reactivity.

Table 4. Emotional and psychotic stress reactivity as mediators of the association of childhood trauma and clinical outcomes

Note: Results adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, centre, comorbid major depressive and anxiety disorders and time to follow-up. Childhood trauma assessed with the CTQ. Illness severity assessed with the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI). Level of functioning assessed with the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF). Unusual thought content, perceptual abnormalities, anxiety and tolerance to normal stress assessed with the Comprehensive Assessment of At Risk Mental State (CAARMS). N, sample size, 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

In exploratory analyses, there was no evidence for a direct effect of childhood trauma on transition status and no mediation via stress reactivity (see online Supplementary material 7).

Discussion

Main findings

Using an experience sampling design, we found strong evidence that minor daily stressors were associated with emotional and psychotic stress reactivity in UHR individuals (H1). Childhood trauma modified the effect of daily stressors on negative affect and psychotic experiences, with more intense psychotic experiences and stronger increases in negative affect for individuals exposed to high levels of childhood trauma (H2). In addition, we found some evidence to suggest stress reactivity predicts clinical outcomes at follow-up (H3). Finally, there was partial evidence that stress reactivity mediates the association of childhood trauma and clinical outcomes (H4).

Methodological considerations/limitations

The reported findings should be interpreted in light of several methodological considerations. First, childhood trauma was measured with a retrospective self-report questionnaire. A common concern about retrospective self-report is that recall bias and cognitive distortions might lead to invalid ratings (Dill et al., Reference Dill, Chu, Grob and Eisen1991; Saykin et al., Reference Saykin, Gur, Gur, Mozley, Mozley, Resnick, Kester and Stafiniak1991; Morgan and Fisher, Reference Morgan and Fisher2007; Susser and Widom, Reference Susser and Widom2012; Colman et al., Reference Colman, Kingsbury, Garad, Zeng, Naicker, Patten, Jones, Wild and Thompson2016). However, good reliability and validity for these measures have been reported in individuals with psychosis (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Craig, Fearon, Morgan, Dazzan, Lappin, Hutchinson, Doody, Jones, McGuffin, Murray, Leff and Morgan2011). Similar levels of agreement between the self-report and interviewer-rated retrospective reports of childhood trauma have been observed in individuals with first-episode psychosis and population-based controls (Gayer-Anderson et al., Reference Gayer-Anderson, Reininghaus, Paetzold, Hubbard, Beards, Mondelli, Di Forti, Murray, Pariante and Dazzan2020). Other types of childhood adversity not assessed (e.g. bullying victimisation) might also be relevant (Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Hoy and Shannon2016). Second, ESM is a burdensome research method, which may lead to sampling and selection bias. For example, one way this may have operated on findings may be that individuals with more intense symptoms may have been underrepresented in the sample, as assessment burden may have discouraged eligible individuals with severe symptoms from participation. In addition, it may be more challenging for individuals with more severe symptoms to reach sufficient compliance, which may lead to underrepresentation due to the exclusion of these participants. However, we found no differences in clinical characteristics at baseline when comparing participants included in the analysis to individuals for whom ESM data were not available. Third, follow-up intervals varied, which was accounted for by controlling for time to follow-up and conducting sensitivity analyses with a restricted sample (leading to similar results in terms of magnitude of associations but some variation in statistical significance due to varying sample sizes). Fourth, unmeasured confounders (e.g. polygenic risk) may have influenced the reported findings. Fifth, although an increasingly common finding in the field (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Velthorst, Nieman, Linszen, Umbricht and de Haan2011; Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Yuen, McGorry, Yung, Lin, Wood, Lavoie and Nelson2016; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Yuen, Lin, Wood, McGorry, Hartmann and Yung2016; Formica et al., Reference Formica, Phillips, Hartmann, Yung, Wood, Lin, Amminger, McGorry and Nelson2020), we need to consider the small number of nine individuals (11%) who transitioned to psychosis within the follow-up period. The findings should therefore be re-evaluated in a larger sample with higher transition rates. In addition, comorbidity, especially comorbid major depressive and anxiety disorders, should be taken into account. Therefore, all analyses were controlled for comorbid major depressive and anxiety disorders. Sixth, the use of a composite stress measure should be critically discussed. In line with previous studies, we aggregated event-related, activity-related and social stress for each beep to reduce multiple testing (Pries et al., Reference Pries, Klingenberg, Menne-Lothmann, Decoster, van Winkel, Collip, Delespaul, De Hert, Derom, Thiery, Jacobs, Wichers, Cinar, Lin, Luykx, Rutten, van Os and Guloksuz2020; Klippel et al., Reference Klippel, Schick, Myin-Germeys, Rauschenberg, Vaessen and Reininghaus2021). Still, type I error should be taken into account when interpreting the results.

Comparison with previous research

In accordance with previous ESM studies, we found that momentary stress was associated with small to moderate increases in negative affect and psychotic experiences and moderate decreases in positive affect in UHR individuals (Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Kempton, Valmaggia, Craig, Garety, Onyejiaka, Gayer-Anderson, So, Hubbard, Beards, Dazzan, Pariante, Mondelli, Fisher, Mills, Viechtbauer, McGuire, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016b; van der Steen et al., Reference van der Steen, Gimpel-Drees, Lataster, Viechtbauer, Simons, Lardinois, Michel, Janssen, Bechdolf and Wagner2017).

When considering the role of childhood trauma and stress reactivity in clinical trajectories, several possibilities of how these may combine with each other may be relevant (Schwartz and Susser, Reference Schwartz, Susser, Schwartz, Susser, Morabia and Bromet2006; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan, Boydell, Kirkbride, Doody and Jones2014). Following Morgan et al. (Reference Morgan, Reininghaus, Fearon, Hutchinson, Morgan, Dazzan, Boydell, Kirkbride, Doody and Jones2014), we investigated both effect modification and mediation in the same analyses. In accordance with suggested models and recent ESM studies, we found that childhood trauma amplifies reactivity to minor stress in daily life (Hammen et al., Reference Hammen, Henry and Daley2000; Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, van Os, Schwartz, Stone and Delespaul2001; Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Kuhn and Prescott2004; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Charalambides, Hutchinson and Murray2010; Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Gayer-Anderson, Valmaggia, Kempton, Calem, Onyejiaka, Hubbard, Dazzan, Beards, Fisher, Mills, McGuire, Craig, Garety, van Os, Murray, Wykes, Myin-Germeys and Morgan2016a; Rauschenberg et al., Reference Rauschenberg, van Os, Cremers, Goedhart, Schieveld and Reininghaus2017). Furthermore, we found some evidence that stress reactivity predicted clinical outcomes at follow-up. This extends findings from a previous ESM study in the general population and an observational study in patients with first-episode psychosis (Conus et al., Reference Conus, Cotton, Schimmelmann, McGorry and Lambert2009; Collip et al., Reference Collip, Wigman, Myin-Germeys, Jacobs, Derom, Thiery, Wichers and van Os2013). Going one step further, there was some evidence that stress reactivity mediated the association of childhood trauma and clinical outcomes at follow-up. High levels of childhood trauma were associated with an increased stress reactivity, which, in turn, was associated with worse clinical outcomes at follow-up. Hence, this tentatively suggests that childhood trauma may both modify stress reactivity and exert detrimental effects via stress reactivity and push individuals along more severe clinical trajectories. Overall, this adds evidence in support of a mediated synergy model (Hafeman and Schwartz, Reference Hafeman and Schwartz2009).

Conclusion

Taken together, our findings underscore the relevance of reactivity to daily stressors as a putative mechanism linking childhood trauma with clinical outcomes in UHR individuals. Adding evidence to the mediated synergy model, the study suggests early adversity in childhood links to more severe clinical trajectories via, and in interaction with, subsequently elevated stress reactivity in adulthood. Therefore, the findings underline the relevance of ecological momentary interventions targeting stress reactivity in daily life (e.g. EMIcompass, a transdiagnostic ecological momentary intervention for improving resilience in youth; Schick et al., Reference Schick, Paetzold, Rauschenberg, Hirjak, Banaschewski, Meyer-Lindenberg, Wellek, Boecking and Reininghaus2020) as an important next step towards improving clinical outcomes in UHR individuals at an early stage (Addington et al., Reference Addington, Marshall and French2012; Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, Klippel, Steinhart and Reininghaus2016, Reference Myin-Germeys, Kasanova, Vaessen, Vachon, Kirtley, Viechtbauer and Reininghaus2018; Reininghaus, Reference Reininghaus2018; Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Klippel, Steinhart, Vaessen, van Nierop, Viechtbauer, Batink, Kasanova, van Aubel, van Winkel, Marcelis, van Amelsvoort, van der Gaag, de Haan and Myin-Germeys2019).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000251

Data

The data will not be available due to their sensitive nature (UHR status) and the fact that participants did not provide consent to the publication.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the participants and all researchers involved in the data collection.

Financial support

This study was supported by the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (grant number HEALTH-F2-2009-241909, Project EU-GEI), the Wellcome Trust (grant number WT087417) to CM, a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship of the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (grant number NIHR-PDF-201104065), a Medical Research Council Fellowship to MK (grant number MR/J008915/1), the Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre, National Institute for Health Research, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and a Heisenberg professorship from the German Research Foundation (grant number 389624707) to UR.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Appendix

EU-GEI High Risk Study – group author list

Philip McGuire1, Lucia R. Valmaggia2, Matthew J. Kempton1, Maria Calem1, Stefania Tognin1, Gemma Modinos1, Lieuwe de Haan3, Mark van der Gaag4,5, Eva Velthorst3,6, Tamar C. Kraan3, Nadine Burger5, Daniella S. van Dam3, Neus Barrantes-Vidal7,8,9,10, Tecelli Domínguez-Martínez7, Paula Cristóbal-Narváez7, Thomas R. Kwapil8, Manel Monsonet-Bardají7, Lídia Hinojosa7, Anita Riecher-Rössler11, Stefan Borgwardt11, Charlotte Rapp11, Sarah Ittig11, Erich Studerus11, Renata Smieskova11, Rodrigo Bressan12, Ary Gadelha12, Elisa Brietzke13, Graccielle Asevedo12, Elson Asevedo12, Andre Zugman12, Stephan Ruhrmann14, Dominika Gebhard14, Julia Arnhold15, Joachim Klosterkötter14, Dorte Nordholm16, Lasse Randers16, Kristine Krakauer16, Tanya Louise Naumann16, Louise Birkedal Glenthøj16, Merete Nordentoft16, Marc De Hert17, Ruud van Winkel17, Barnaby Nelson18, Patrick McGorry18, Paul Amminger18, Christos Pantelis18, Athena Politis18, Joanne Goodall18, Gabriele Sachs19, Iris Lasser19, Bernadette Winklbaur19, Mathilde Kazes20, Claire Daban20, Julie Bourgin20, Olivier Gay20, Célia Mam-Lam-Fook20, Marie-Odile Krebs20, Bart P. Rutten21, Jim van Os1,22

1Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, London, UK; 2Department of Psychology, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London, London, UK; 3Department of Psychiatry, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 4Department of Clinical Psychology, VU University and Amsterdam; Public Mental Health Research Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 5Department of Psychosis Research, Parnassia Psychiatric Institute, The Hague, The Netherlands; 6Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, USA; 7Departament de Psicologia, Clínica i de la Salut, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; 8Departament de Salut Mental, Sant Pere Claver-Fundació Sanitària, Barcelona, Spain; 9Spanish Mental Health Research Network, CIBERSAM, Madrid, Spain; 10Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, USA; 11Center for Gender Research and Early Detection, Psychiatric University Clinics Basel, Basel, Switzerland; 12LiNC – Lab Interdisciplinar Neurociências Clínicas, Depto Psiquiatria, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de São Paulo – UNIFESP, São Paulo, Brazil; 13Pogram for cognition and Intervention in Individuals in At-Risk Mental States (PRISMA), Department of Psychiatry, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; 14Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; 15Psyberlin, Berlin, Germany; 16Mental Health Center Copenhagen and Center for Clinical Intervention and Neuropsychiatric Schizophrenia Research, CINS, Mental Health Center Glostrup, Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Copenhagen, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; 17Department of Neuroscience, University Psychiatric Centre, Catholic University Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 18Centre for Youth Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; 19Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria; 20University Paris Descartes, Hôpital Sainte-Anne, C'JAAD, Service Hospitalo-Universitaire, Inserm U894, Institut de Psychiatrie, Paris, France; 21Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands and 22Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands.