Introduction

Depression affects more than 300 million people worldwide, with a global prevalence of approximately 4.4% (Friedrich, Reference Friedrich2017). Women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression as men (Albert, Reference Albert2015), and depressive symptoms are associated with reproductive events such as menstruation, childbirth and menopause (Soares and Zitek, Reference Soares and Zitek2008; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Huber, Issel and Warren-Findlow2015; Hofmeister and Bodden, Reference Hofmeister and Bodden2016). A similar trend exists with suicide rates for women during climacteric periods (Kulkarni, Reference Kulkarni2018).

Prior studies have investigated the prevalence and risk of depression during perimenopause. However, most studies used a binary category of menopause (postmenopausal v. premenopausal) and reported a lack of association, possibly due to the low prevalence of depressive symptoms and the use of relatively small sample sizes (Maki et al., Reference Maki, Kornstein, Joffe, Bromberger, Freeman, Athappilly, Bobo, Rubin, Koleva, Cohen and Soares2018). The menopausal transition (MT) is a complex process comprising multiple stages, ranging from pre-menopause, early MT, late MT, to post-menopause, all of which accompany changes in female sex hormones and various aspects of physical health (Derby et al., Reference Derby, Crawford, Pasternak, Sowers, Sternfeld and Matthews2009; Harlow et al., Reference Harlow, Gass, Hall, Lobo, Maki, Rebar, Sherman, Sluss, de Villiers and Group2012; Kozakowski et al., Reference Kozakowski, Gietka-Czernel, Leszczynska and Majos2017). It is important to identify the critical period within the MT during which women become vulnerable to mental disorders to provide insights into the optimal timing to ensure timely intervention; however, there is still limited evidence on the association between specific menopausal stages and depressive symptoms.

This study aimed to examine the association between menopausal stages and the prevalence of depressive symptoms and suicidality in a large sample of middle-aged Korean women.

Methods

Setting and studying the population

The Kangbuk Samsung Health Study was a cohort study of Korean men and women who underwent comprehensive annual or biennial examinations at the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Total Healthcare Centers in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Ryu, Choi, Zhang, Cho, Kwon, Hyun, Lee, Kim, Jung, Yun, Ahn, Rampal, Zhao, Suh, Chung, Shin, Pastor-Barriuso and Guallar2016).

The study population consisted of women aged 40–65 years who underwent comprehensive health examinations at the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Total Healthcare Centers in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea, between 2015 and 2018 (N = 59 940). Among the 59 940 women, 14 763 were excluded for the following reasons: history of cancer (n = 3962); history of hysterectomy or ovariectomy (n = 4422); history of premature menopause (n = 256); history of artificially-induced menopause due to radiation (n = 209), chemotherapy (n = 383) or other (n = 629); currently receiving hormone replacement therapy (n = 1672, as such interventions can affect menopausal symptoms); currently taking an oral contraceptive (n = 320) or currently pregnant (n = 6); history of mental illness diagnoses such as panic disorder, claustrophobia, depression and others (n = 2357); currently taking anxiety drugs (n = 703), antidepressants or other neuropsychological medications (n = 869); and missing data related to depressive symptoms and suicidality (n = 3779). As some individuals met more than one exclusion criteria, the total number of women ultimately included in the study was 45 177.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (IRB No. KBSMC 2020-08-042). The requirement for informed consent was waived because we used non-identified retrospective data that were routinely collected during the health screening process.

Measurements

Data on demographic factors, socioeconomic status, health behaviours, dietary intake, medical history (including a history of physician-diagnosed mental illness such as panic disorder, claustrophobia or depression) and medication use (including neuropsychiatric medications such as anxiety drugs and antidepressants) were collected using standardised, structured, self-administered questionnaires. Physical activity was assessed using the validated Korean version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (Oh et al., Reference Oh, Yang, Kim and Kang2007; Ryu et al., Reference Ryu, Chang, Jung, Yun, Kwon, Choi, Kim, Cho, Suh, Cho, Chung, Shin and Kim2015). Health-enhancing physical activity (HEPA) was defined as physical activity that meets either of the following two criteria: (i) vigorous-intensity activity on 3 or more days per week for a total of 1500 metabolic equivalent (MET) min/week, or (ii) 7 days of any combination of walking, moderate-intensity or vigorous-intensity activities achieving at least 3000 MET min/week.

Sleep duration and quality were assessed using the Korean version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Regarding subjective sleep quality, the response categories of the PSQI were very good, fairly good, fairly bad and very bad. The last two categories were defined as poor subjective sleep quality.

Anthropometric parameters and sitting blood pressure (BP) were measured by trained nurses. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ⩾25 kg/m2 according to the criteria for obesity in Asians. Hypertension was defined as BP ⩾ 140/90 mmHg or current use of antihypertensive medication.

Fasting blood measurements included glucose, haemoglobin A1c, insulin, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and lipid profiles. The homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as follows: fasting blood insulin (uU/ml) × fasting blood glucose (mg/dl)/405. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting serum glucose ⩾ 126 mg/dl, haemoglobin A1c ⩾ 6.5% or current use of insulin or medications for diabetes.

Assessment of menopausal stage

The participants were classified into four groups according to menopausal stage based on the Stage of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10 criteria as follows: (1) premenopause (having regular menstrual periods), (2) early MT (having a persistent difference of 7 or more days in the length of consecutive cycles), (3) late MT (occurrence of amenorrhoea of ⩾60 days) and (4) post-menopause (amenorrhoea for ⩾1 year).

Assessment of depression, suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour

The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CESD) was used to evaluate depressive symptoms within the past week using the Korean version of the CESD scale; the internal consistency of the Korean version has been reported to range from 0.84 to 0.91. The CESD is composed of 20 items, each rated on a scale from 0 to 3, with total scores ranging from 0 (lowest) to 60 (highest) (Farmer et al., Reference Farmer, Locke, Moscicki, Dannenberg, Larson and Radloff1988; Cho and Kim, Reference Cho and Kim1998; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hong, Lee, Kwak, Shin, Jang, Oh, Lee, Jeon and Hwang2007). In a previous study validating the Korean version of the CESD scale, the optimal cut-off point was suggested as 24/25, the point that best corresponds to a clinical diagnosis of depression. In contrast, a CESD score of 16 has been traditionally used as an optimal cut-off for the detection of depressive symptoms. Therefore, the presence of depressive symptoms was defined as a CESD score of ⩾16, and the presence of case-level depression was defined by a cut-off score of ⩾25.

Suicidal ideation was also assessed via a self-administered questionnaire with specific questions, such as ‘In the last year, have you ever thought about wanting to die?’ Suicidal behaviour was determined based on a question, ‘Have you attempted suicide in the last year?’. Responses to the questions were dichotomous as either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’.

Statistical analyses

The characteristics of the study participants were explored according to CESD score categories. CESD scores were categorised as moderately (16–24 points) and severely depressed (⩾25 points). To test for linear trends, the number of categories was used as continuous variables in the regression models.

We estimated the prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for CESD scores of 16–24 and ⩾25 for the early MT, late MT and post-menopause stages compared to the pre-menopause stage using participants with a CESD score <16 as the reference group in multinomial logistic regression models. Moreover, to evaluate the association of suicidal ideation across menopausal stages, we used a logistic regression model to estimate the odds ratios with 95% CIs for suicidal ideation. We used three models to progressively reduce confounding associations. We initially adjusted for age and then further adjusted for the centre, year of screening examination, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity level, total energy intake, BMI, educational level, antihypertensive medication, parity and age at menarche. In addition, to evaluate the effects of psychological symptoms around the period of the MT, sleep duration and sleep quality were adjusted.

Additionally, we performed stratified analyses in pre-specified subgroups defined by BMI (<25 v. ⩾25 kg/m2), age at menarche (<12 v. ⩾12 years), parity (0 v. ⩾1 time), sleep quality (good v. poor), smoking status (never smoker v. ex-smoker or current smoker), alcohol intake (<10 v. ⩾10 g of alcohol per day) and physical activity (no HEPA v. HEPA). Interactions by subgroup were tested using likelihood ratio tests comparing models with and without multiplicative interaction terms. All p values were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. We used STATA version 13.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) for the data analyses.

Results

The mean (standard deviation) age of the 45 177 study participants was 47.3 (6.5) years (online Supplementary Table S1). The prevalence of pre-menopause, early MT, late MT and post-menopause was 49.7, 15.5, 8.7 and 26.1%, respectively. Compared to premenopausal women, participants in the later menopausal stages were more likely to be older and engage in HEPA. They also had higher rates of hypertension and diabetes, BMI, BP, glucose level and HOMA-IR, and were more likely to take dyslipidaemia medication and have unfavourable lipid profiles.

Overall, the prevalence of CESD scores of 16–24 and ⩾25 was 7.6% and 2.8%, respectively (Table 1). Participants with higher CESD scores were more likely to be older, and current smokers, to drink alcohol and have shorter sleep duration and have poor sleep quality. They were also more likely to have higher parity and prevalence of hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia medication use, as well as higher BMIs, glucose levels and HOMA-IR.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants by depression category

BP, blood pressure; CESD, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HEPA, health-enhancing physical activity; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

a Means (standard deviations).

b <12 years.

c ⩾3 times.

d ⩾10 g of ethanol per day.

e ⩾college graduate; data are expressed as.

f Medians (interquartile ranges), or percentages.

g Among 24 840 participants with plausible estimated energy intake levels (within three standard deviations from the log-transformed mean energy intake).

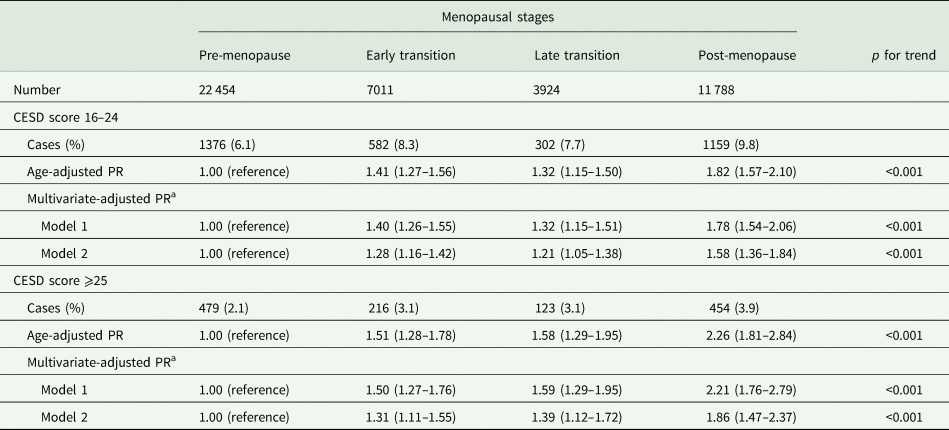

Menopausal stages were positively associated with depressive symptoms in a dose-dependent manner (Table 2). After adjustment for age, centre, year of a screening exam, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity level, total energy intake, BMI, educational level, antihypertensive medication, parity and age at menarche, the PR (95% CI) for CESD scores of 16–24 comparing early MT, late MT and post-menopause stages to the pre-menopausal stage was 1.40 (1.26–1.55), 1.32 (1.15–1.51) and 1.78 (1.54–2.06), respectively. The corresponding PR (95% CIs) for CESD scores ⩾25 was 1.50 (1.27–1.76), 1.59 (1.29–1.95) and 2.21 (1.76–2.79), respectively (Table 2, model 1). After further adjustments for sleep quality and sleep duration, and the history of suicidal behaviour, the association between the menopausal stage and depressive symptoms was slightly attenuated although remained statistically significant (Table 2, model 2; online Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2. Prevalence ratiosa (95% CI) of depression by menopausal stage

CESD, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression; CI, confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio.

a Estimated from multinomial logistic regression models using CESD scores as outcomes categorised as <16, 16–24 and ⩾25. Multivariable model 1 was adjusted for age, centre, year of screening examination, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity level, total energy intake, body mass index, educational level, antihypertensive medication, parity and age at menarche; model 2: model 1 plus an adjustment for sleep duration and quality.

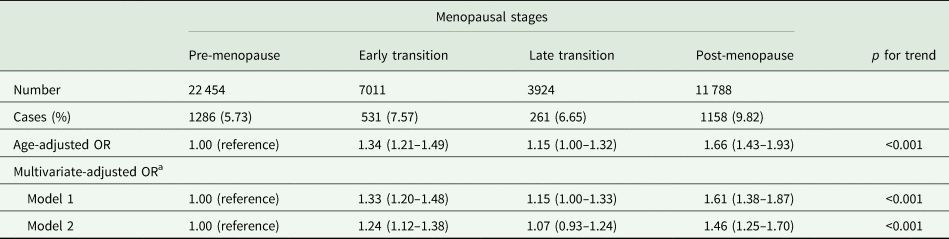

A total of 3236 women (7.16%) reported suicidal ideation. Menopausal stages were positively associated with suicidal ideation (Table 3). There were 1286 (5.73%) cases of suicidal ideation during the pre-menopause stage, 531 (7.57%) during the early MT, 261 (6.65%) during the late MT and 1158 (9.8%) during the post-menopause stage. The multivariable-adjusted PRs for suicidal ideation comparing early MT, late MT and post-menopause stages to the pre-menopause stage were 1.33 (1.20–1.48), 1.15 (1.00–1.33) and 1.61 (1.38–1.87) (p for trend <0.001), respectively. Although attenuated after adjusting for sleep duration and sleep quality, the association with the early MT and post-menopause stages remained statistically significant. However, a significantly higher prevalence of suicidal ideation during late MT compared with pre-menopause was no longer observed. After further adjustment for the history of suicidal behaviour, the associations remained virtually unchanged (online Supplementary Table S3). Depressive symptoms (CESD scores ⩾25) showed a tendency towards a consistently higher prevalence of suicidal behaviour across menopausal stages (online Supplementary Table S4). In additional analyses without excluding women with a history of psychiatric diagnosis, the results were slightly attenuated but overall patterns remained similar to those of the original analyses (online Supplementary Table S5). Analyses using binary category (pre- v. postmenopausal stages) showed similar patterns (online Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). When we evaluated the prevalence of (i) isolated depression within the past week, (ii) isolated suicidal ideation within the past 12 months and (iii) concurrent depression and suicidal ideation (i.e. women who reported having both depression and suicidal ideation at a given visit) across menopausal stages, overall patterns of association were similar to the findings of the original analyses for all three dependent variables, with the post-menopause stage being associated with the highest prevalence of either isolated or concurrent depression and suicidal ideation (online Supplementary Table S8).

Table 3. Odd ratiosa (95% CI) of suicidal ideation by menopausal stage

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

a Estimated from binomial logistic regression models. Multivariable model 1 was adjusted for age, centre, year of a screening exam, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity level, total energy intake, body mass index, educational level, antihypertensive medication, parity and age at menarche; model 2: model 1 plus an adjustment for sleep duration and quality.

In the subgroup analyses, the association between the menopausal stage and depressive symptoms differed by obesity, defined as BMI ⩾ 25 kg/m2, with a stronger association in obese women than in non-obese women (p for interaction 0.002) (online Supplementary Table S9). The association between the menopausal stage and suicidal ideation was stronger in women with alcohol intake ⩾10 v. <10 g/day (p for interaction 0.014) (online Supplementary Table S10). Otherwise, the associations did not significantly differ among the subgroups.

Discussion

In this large study of middle-aged Korean women, depressive symptoms and suicidality were significantly associated with menopausal stages and started to increase from the early transition stage. This association remained significant after adjusting for possible confounders. Our results provide the time window during which both depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation are more likely to occur among women in the early to late transition stage who may benefit from appropriate screening measures.

Previous epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that the prevalence and risk of depressive symptoms markedly rise during peri- and post-menopause (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Soares, Vitonis, Otto and Harlow2006; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Sammel, Lin and Nelson2006, Reference Freeman, Sammel, Boorman and Zhang2014; Woods et al., Reference Woods, Smith-DiJulio, Percival, Tao, Mariella and Mitchell2008; Timur and Sahin, Reference Timur and Sahin2010; Bromberger et al., Reference Bromberger, Kravitz, Chang, Cyranowski, Brown and Matthews2011; Colvin et al., Reference Colvin, Richardson, Cyranowski, Youk and Bromberger2017). A cross-sectional study of 685 women found that, compared to premenopausal women, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women had a twofold higher risk of developing depressive symptoms (Timur and Sahin, Reference Timur and Sahin2010). Another cross-sectional study reported that major depression was significantly higher when women were in the late perimenopausal or postmenopausal period relative to when they were premenopausal or early perimenopausal (Colvin et al., Reference Colvin, Richardson, Cyranowski, Youk and Bromberger2017). A longitudinal study from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) cohort of 221 women demonstrated that women were about two to four times more likely to experience a major depressive episode during or immediately after MT, with the highest risk in postmenopausal women (Bromberger and Kravitz, Reference Bromberger and Kravitz2011). However, as these previous studies did not differentiate between early and late MT or between perimenopausal and postmenopausal stages, it is unclear whether there are differences in the prevalence of depressive symptoms across menopausal stages. Studies that did incorporate more specific menopausal stages reported that the likelihood of depressive symptoms tended to peak in the late MT, or immediately before menopause, and slowly wanes thereafter, independent of age (Bromberger et al., Reference Bromberger, Matthews, Schott, Brockwell, Avis, Kravitz, Everson-Rose, Gold, Sowers and Randolph2007; Woods et al., Reference Woods, Smith-DiJulio, Percival, Tao, Mariella and Mitchell2008). In a 14-year longitudinal study from the Penn Ovarian Aging Study, the risk of depressive symptoms was higher before the final menstrual period and decreased thereafter (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Sammel, Boorman and Zhang2014). Our findings are largely consistent with prior findings in that the likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms markedly increases during the MT, especially towards the later stages compared with the premenopausal period. In addition, the associations with advancing menopausal stages do not seem to be fully explained by increasing age. However, contrary to previous reports, our findings show that the prevalence of depressive symptoms was higher in postmenopausal women than in women in MT. Depression is a multifactorial condition that can be attributed to genetic, psychosocial, demographic or cultural factors (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Mokonogho and Kumar2019). It is thus possible that some unmeasured factors inherent to our study population that are distinct from those of Western populations, which have been extensively studied previously, may have led to the differences in patterns. Our findings need to be further evaluated in future longitudinal studies of other Asian populations.

Similarly, we found the highest prevalence of suicidal ideation in postmenopausal women among all menopausal stages. There is relatively limited evidence on suicidality in peri- and post-menopausal women; however, our study findings are consistent with several prior studies (Pinto-Meza et al., Reference Pinto-Meza, Usall, Serrano-Blanco, Suarez and Haro2006; Kornstein et al., Reference Kornstein, Young, Harvey, Wisniewski, Barkin, Thase, Trivedi, Nierenberg and Rush2010). The reasons underlying the heightened risk of suicidal ideation associated with the postmenopausal stage in our study are not clear. A previous study examined the association between suicide attempts and menstrual stage and reported that women who had experienced menopause and amenorrhoea had low oestradiol and progesterone levels, and women with low gonadal hormones had suicide attempts of greater severity (Baca-Garcia et al., Reference Baca-Garcia, Diaz-Sastre, Ceverino, Perez-Rodriguez, Navarro-Jimenez, Lopez-Castroman, Saiz-Ruiz, Leon and Oquendo2010). Existing evidence supports the association of oestrogen and increased serotonin activity and low serotonergic function due to a drop in oestrogen levels (McQueen et al., Reference McQueen, Wilson and Fink1997; Carretti et al., Reference Carretti, Florio, Bertolin, Costa, Allegri and Zilli2005; Berman et al., Reference Berman, Puri, Chandrala, Puri, Macgregor, Liverman and Klein2006), which may increase suicide risk in those with predisposing factors (Arango et al., Reference Arango, Underwood, Boldrini, Tamir, Kassir, Hsiung, Chen and Mann2001; Oquendo and Mann, Reference Oquendo and Mann2001), suggesting that suicidality in postmenopausal women may at least partly have neurobiological underpinnings. Environmental factors also play a crucial role in the association between menopause and suicide. In particular, the role of family was found to be significant in women experiencing menopause. The emotional support of a spouse during the climacteric period was an important protective factor, whereas the lack of family support could lead to increased suicide (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Verjee, Bener and Gerber2013). Our study is supported by previous studies that found that MT and post-menopause are periods of not only physical but also psychological vulnerability, demonstrating that women in these stages have an elevated likelihood of depression and suicidal ideation. Optimal intervention strategies need to be developed to prevent depression and suicide attempts in this at-risk population.

In our subgroup analysis, we observed a stronger association between the menopausal stage and depressive symptoms in women with a high BMI. Middle-aged women in MT are predisposed to being obese due to the ageing process, changes in hormonal status and/or mood changes that may prompt maladaptive coping behaviours such as stress eating, and obesity may also exacerbate depressive symptoms (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Sammel, Lin and Nelson2006; Blumel et al., Reference Blumel, Chedraui, Aedo, Fica, Mezones-Holguin, Baron, Bencosme, Benitez, Bravo, Calle, Flores, Espinoza, Gomez, Hernandez-Bueno, Laribezcoa, Martino, Lima, Monterrosa, Mostajo, Ojeda, Onatra, Sanchez, Tserotas, Vallejo, Witis and Zuniga2015; Schreiber and Dautovich, Reference Schreiber and Dautovich2017). Furthermore, obesity is related to increased severity and frequency of menopausal symptoms or physical limitations that may cause considerable discomfort or irritability and, in turn, may negatively affect the psychological well-being of women. A study found that obese women experienced more frequent vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes, sweating and weight gain) than non-obese women, and the association between obesity and vasomotor symptoms was strongest in postmenopausal women (Koo et al., Reference Koo, Ahn, Lim, Cho and Park2017). Compared to women with a normal BMI, overweight and obese women were more likely to have physical limitations, which is also significantly associated with depression (Tseng et al., Reference Tseng, El Khoudary, Young, Farhat, Sowers, Sutton-Tyrrell and Newman2012). In addition, obesity may be associated with lower self-esteem, although this association may be population-specific. For instance, an inverse association between obesity and depressive symptoms was found in postmenopausal women with lower education levels, whereas no such association was observed in better-educated women (Jasienska et al., Reference Jasienska, Ziomkiewicz, Gorkiewicz and Pajak2005). Moreover, there are reports that body image, rather than obesity, is associated with lower self-esteem, which can be a significant predictor of depressive symptoms (Kékes Szabó, Reference Kékes Szabó2015; Noh et al., Reference Noh, Kwon, Yang, Cheon and Kim2018). A study conducted on midlife women in the USA suggested that depressive symptoms were not directly correlated with weight per se in postmenopausal women after adjustment for available confounders (Schreiber and Dautovich, Reference Schreiber and Dautovich2017). In Korean culture, which has relatively high societal pressure for thinness, women tend to overestimate their weight status and develop a distorted body image, which is also observed in other East Asian cultures (Noh et al., Reference Noh, Kwon, Yang, Cheon and Kim2018). Therefore, it is likely that being overweight or obese may be much more of a distressing factor for women in Korea compared to those in Western countries. However, given that our study is cross-sectional, the directionality of the association is unclear; further studies should investigate how obesity mediates the association between menopausal stages and depressive symptoms, and whether there are cultural variations in the relationship.

We also found that higher alcohol intake was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation in the late MT and post-menopause stage. It is uncertain whether alcohol consumption is driven by existing depressive symptoms, or whether it causes or worsens depressive symptoms and leads to suicidal ideation. It has been reported that depression and alcoholism have strong reciprocal relationships and frequently co-occur (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Fiellin and O'Connor2005). There are also reports that alcohol consumption may have a causal effect on the development of major depression (Flensborg-Madsen et al., Reference Flensborg-Madsen, Mortensen, Knop, Becker, Sher and Gronbaek2009; Boden and Fergusson, Reference Boden and Fergusson2011). While there is a lack of data on the specific effect of alcohol consumption on the association between menopausal stages and depression, there is a plethora of evidence suggesting that drinking is strongly associated with suicidal ideation (Norstrom and Rossow, Reference Norstrom and Rossow2016), and the association is stronger in women than in men (Yi et al., Reference Yi, Jung, Kimm, Sull, Lee, Lee and Ohrr2016). Studies have suggested that as women reach menopause, various environmental or psychosocial factors such as retirement and loss of loved ones, along with changes in body composition, may affect or exacerbate their drinking habits (Milic et al., Reference Milic, Glisic, Voortman, Borba, Asllanaj, Rojas, Troup, Kiefte-de Jong, van Beeck, Muka and Franco2018). Based on the data from the SWAN study, although excessive alcohol consumption may not increase during MT, it is a period of instability that may be associated with changes in alcohol-related behaviours (Peltier et al., Reference Peltier, Verplaetse, Roberts, Moore, Burke, Marotta, Phillips, Smith and McKee2020), which may also be driven by affective factors such as negative mood, retained stress and depressive symptoms related to menopause which may trigger suicidal ideation. Nevertheless, due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding the role of alcohol use in the relationship between MT and depressive symptoms. Further longitudinal studies are needed to confirm our findings.

The present study has several limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional design of our study, causality in the association between menopausal stages and depressive symptoms could not be determined. Second, the diagnosis of depressive symptoms was not made clinically by a physician and was based on a self-administered questionnaire. However, the CESD is one of the most widely used tools in population-based research settings to assess depressive symptoms and has good validity and reliability (Luckett et al., Reference Luckett, Butow, King, Oguchi, Heading, Hackl, Rankin and Price2010). Third, we did not consider the effect of vasomotor symptoms due to the lack of data. Previous reports have documented the close associations between depression, sleep and vasomotor symptoms in peri-menopausal women (Eichling and Sahni, Reference Eichling and Sahni2005; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Soares, Vitonis, Otto and Harlow2006; Alvaro et al., Reference Alvaro, Roberts and Harris2013; Worsley et al., Reference Worsley, Bell, Kulkarni and Davis2014). Future studies should examine whether the observed association between MT and depression is modified by the presence of vasomotor symptoms. Fourth, although past-year suicidal ideation has been widely implemented in psychiatric surveys and epidemiologic studies (Klimes-Dougan et al., Reference Klimes-Dougan, Safer, Ronsaville, Tinsley and Harris2007; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Ollmann, Miché, Venz, Hoyer, Pieper, Höfler and Beesdo-Baum2019), it does not allow for estimating the precise onset time of suicidal ideation. In analyses using isolated depression, isolated suicidal ideation and concurrent depression and suicidal ideation (i.e. women who reported having both depression and suicidal ideation at a given visit) as a dependent variable, overall patterns of association across menopausal stages were similar to the findings of the original analyses. However, given the lack of information on the exact timing of suicidal ideation with the timeframe of the inquiry being within the past 12 months, we cannot rule out the possibility that some women may have reported the events that had occurred in the prior stage. Further large-scale longitudinal studies are warranted to confirm the association between MT and suicidality. Lastly, our study subjects consisted mostly of relatively healthy Korean women with high socioeconomic status, which may limit the generalisability of our findings to other populations with different races/ethnicities or demographic characteristics.

The present study has several strengths. First, this was a large-scale study that examined women's psychological health across menopausal stages in Korea. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine women's psychological health based on the four distinctive menopausal stages in an Asian population. Second, this study used the STRAW + 10, which is known to be the current standard measure for classifying the specific menopausal stages. Because most women's health studies, especially concerning menopause, are based on dichotomous classification, either menopausal or non-menopausal, our study has the great advantage of identifying the menopausal stage and the potential health complications at a certain stage. Third, a wide range of data was obtained through standardised methods, enabling us to examine independent associations between menopausal stages and depressive symptoms.

In conclusion, in this study of middle-aged women, the prevalence of depressive symptoms and suicidality gradually increased with the advancing menopausal stage. Thus, psychological vulnerability around the time of MT should be considered, and a better understanding of the association between menopausal stages and women's mental health may help identify women at risk for depression and suicidality.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000439.

Data

The data are not available to be shared publicly because we do not have permission from the IRB to distribute the data. However, analytical methods are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

Y Chang and S Ryu planned, designed and directed the study, including quality assurance and control. S Ryu analysed the data and designed the analytic strategy of the study. All authors conducted the literature review and prepared the Materials and Methods and Discussion sections of the text. S Ahn, Y Kim and Y Chang drafted the manuscript. All authors interpreted the results and contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (IRB No. KBSMC 2020-08-042).

Patient consent statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital due to the use of a preexisting de-identified dataset.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not applicable.