The General Assembly … Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.Footnote 1

We reaffirm that democracy is a universal value based on the freely expressed will of people to determine their own political, economic, social and cultural systems and their full participation in all aspects of their lives.Footnote 2

This chapter presents an overview of the evolution of the United Nations General Assembly, its most important achievements and remaining weaknesses, and relevance. It argues that the UN Charter should be amended to allow the introduction of a system of weighted voting, to better reflect the relative significance and influence of its 193 members. A particular proposal will be presented, updating the work done by Schwartzberg.Footnote 3 We discuss its merits and limitations and propose that a gradual system of direct election of Assembly members be introduced. By way of example, we also present the UN Charter’s Articles 9–11 on General Assembly composition, functions and powers and how these Articles could be amended to reflect the new system of weighted voting and the enhanced powers that are envisaged for the Assembly under a revised Charter.

Key Achievements and Weaknesses

It is possible to have a lively debate about how representative the UNGA is, including the reasons why the founders of the United Nations embedded in the Charter the principle of one-country-one-vote for the General Assembly (Article 18(1)); indeed, in Chapter 2 we presented the likely most plausible explanation, reflecting the rather uneven distribution of political power at the time and the desire of the Big Four to ensure a UN that would not challenge their national prerogatives. Article 18(2) identifies a number of questions on which decisions of the General Assembly are to be made by a two-thirds majority of the members present and voting, including “recommendations with respect to the maintenance of international peace and security, the election of the non-permanent members of the Security Council, the election of the members of the Economic and Social Council, the admission of new Members to the United Nations, the suspension of the rights and privileges of membership, the expulsion of Members” and, of course, questions relating to the budget.

Other Articles of Chapter IV of the Charter on the General Assembly envisage a dual role; it shall be a body for high-level deliberation, but it will also have administrative oversight of the UN system. We are sympathetic to the views put forward by Grenville Clark – discussed in Chapter 2 – that the Big Four saw the one-country-one-vote system under Article 18(1) as a natural manifestation of the principle of “sovereign equality” of its members and an attempt to create a body that would play a mainly advisory role to the Security Council, which would be the locus of real power within the organization. As noted in Chapter 2, the one-country-one-vote principle undermined at the outset the credibility of the General Assembly and may have been a deliberate attempt to weaken it with respect to the Security Council.

In the early stages of the United Nations – certainly during the first decade and possibly through the late 1950s – the one-country-one-vote principle did not prevent the emergence of a working majority led by the United States and many of its allies in Europe and Latin America, which easily accounted for more than half of the UN membership. This in turn, resulted in the Soviet Union feeling isolated within the General Assembly and exercising its power through repeated use of the veto in the Security Council. During the first ten years of the United Nations, the Soviet Union exercised its veto no less than 80 times, the vast majority of instances used to reject applications for membership from a large number of countries. In sharp contrast, the United States did not exercise its first veto until 1970, a full 25 years after the creation of the UN.Footnote 4 Article 4 of the Charter establishes the criteria for membership, which, in essence requires countries to be “peace-loving states” that accept the obligations that it contains and makes membership conditional upon recommendation of the Security Council. It is clear that in these earlier periods the Soviet Union and the other members of the Council had very different understandings of the meaning of Article 4. Thus, Spain’s application for membership did not succeed until 1955 because of its earlier collaboration with the Axis powers during World War II. Indeed, only ten new members were admitted during the UN’s first ten years because of the Soviet veto.Footnote 5

The first big push for expanded membership came in 1955 when 16 new states were accepted into the organization, with a second wave of new entrants taking place in 1960–1961 when 22 new countries became members, reflecting a quickening in the pace of decolonization. In time, as United Nations membership expanded beyond its original 51 founding nations, the organization was gradually transformed into a body dominated by economically small and (often) politically less influential states. Thus, an Assembly that already in 1945 did not reflect in a meaningful way the economic size, population and influence of its members saw the problem greatly accentuated as its membership expanded in the following decades, particularly in the developing world. For instance, membership of African countries rose from four in 1945 to 42 in 1969 and 55 today or from 5.9 percent of the membership to 28.5 percent today. Of course, along the way, the United Nations became truly universal, with its current 193 members accounting for over 99 percent of world gross national product (GNP) and this has been a remarkable (and welcome) development in its own right.

The first decade of the United Nations did see some important achievements reflecting the prevailing distribution of power and the working majority led by the United States. The first session of the General Assembly took place in London on January 10, 1946, and it dealt with the issue of nuclear weapons. The UN Charter is silent on the issue of nuclear weapons because the San Francisco Conference where the Charter was adopted was concluded six weeks before the explosions in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Against the background of the fearsome destructions caused by these bombs there was an intense debate in policymaking circles, in the academic community, and in the pages of the international press about what the advent of nuclear weapons would mean for the newly created organization: in particular, in light of its stated desire “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war” and the explicit identification in Article 26 of the Security Council’s responsibilities to formulate plans “for the establishment of a system for the regulation of armaments” (see Chapter 9).

Perhaps appropriately, the General Assembly’s first resolution dealt with the problems raised by the discovery of atomic energy and established the Atomic Energy Commission, whose terms of reference include making proposals for the “control of atomic energy to the extent necessary to ensure its use only for peaceful purposes,” and “for the elimination from national armaments of atomic weapons and of all other major weapons adoptable to mass destruction.” In 1947, the Security Council established the Commission for Conventional Armaments to deliver proposals in the area of armaments reduction and delimitation of armed forces more generally. The Commission had limited success. By 1949 the Soviet Union had succeeded in obtaining nuclear weapons of its own and the Cold War entered an intense phase, which saw over the next several decades a substantial accumulation of conventional and nuclear armaments. These developments notwithstanding, the General Assembly did try to strengthen the role of the UN in the negotiation of disarmament agreements. One important achievement was active engagement in the setting up of various fora addressing global disarmament issues, as of the 1950s and early 1960s, including the UN Disarmament Commission (UNDC) and what would eventually become the Conference on Disarmament (CD) in Geneva established in 1978. The precursor body to the CD was initially made up of ten and then 18 members; it had grown to 61 members by 1996 and to 65 members by 2018. The CD in time became the principal venue for the negotiation of various disarmament treaties, including the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention, the 1992 Chemical Weapons Conventions (CWC), and the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, among others (see also Chapter 9).

As a result of these, according to Marin-Bosch “Today over 180 nations are committed, in legally binding, multilateral instruments such as the NPT or in nuclear weapon-free regional treaties, to refrain from acquiring nuclear weapons. And that is very significant.”Footnote 6 A more recent and potentially very important initiative is the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons adopted by 122 nations on July 7, 2017, which prohibits the development, testing, production, stockpiling, transfer, use, or threat of use of nuclear weapons. This initiative was launched with a General Assembly Resolution issued in December 2016 and the Treaty was negotiated with impressive speed in the three-week period leading up to its signing. None of the nuclear weapons states signed it, nor did NATO members approve it, but the Treaty is an eloquent reaffirmation of the idea that the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons has no moral justification whatsoever.

The various arms limitation initiatives cited above spearheaded by the General Assembly have had other positive collateral implications. For instance, in 1967, the nations of Latin America and the Caribbean signed the Treaty of Tlateloleco, in which they committed themselves not to acquire nuclear weapons and secured a legally binding pledge from the nuclear weapon states (NWS) not to use nuclear weapons against them, thereby creating a nuclear-free zone in the region. This in turn, encouraged the signing of similar treaties for other regions of the world including the 1985 Treaty of Rarotonga (South Pacific), the 1995 Treaty of Bangkok (South East Asia), and the 1996 Treaty of Pelindaba (Africa). These treaties are not particularly well known but are significant nevertheless, and the countries that have signed them have, thus far, fulfilled their commitments and therefore, contributed to slowing down nuclear proliferation. Of particular significance in this regard was the 1968 NPT (which entered into force in 1970), which established a clear-cut distinction between non-nuclear weapon states (NNWS) and the then five acknowledged nuclear weapon states. In 1995 when the NPTs signatories met to review their nuclear weapons commitments, the NNWS parties decided to permanently and unconditionally opt out of building nuclear weapons. This sharply highlighted the gap with respect to the NWS that remain unwilling to give up their nuclear weapons. At the time China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States pledged to move toward nuclear disarmament.

In parallel to these efforts, there was also an attempt within the UN system to delineate more clearly the legal underpinnings of the use of nuclear weapons. For instance, in 1993, the World Health Organization, and then the UN General Assembly, sought an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice on the legality of the use of such weapons, given the widespread and damaging health and environmental effects, so eloquently laid out in Jonathan Schell’s 1982 monumental The Fate of the Earth, which also addressed the moral dimension of the use of nuclear weapons. In its advisory opinion of July 8, 1996, the International Court of Justice concluded that “the threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the [applicable] rules of international law,” and reminded states that “[t]here exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective international control” (in particular under the terms of the widely ratified NPT).Footnote 7 These initiatives may have contributed to the five NWS feeling increasingly isolated within the UN on questions of nuclear disarmament. By the 1980s the United States and the Soviet Union had opted for conducting disarmament negotiations outside of the UN framework; for instance, the SALT-I and SALT-II treaties were the results of bilateral negotiations between the two superpowers and did not involve any of the established UN mechanisms. Article VI of the NPT imposes an obligation on its signatories not only to conduct negotiations on nuclear disarmament but actually to conclude such negotiations at some point in the not too distant future.Footnote 8

A second example: In 1948, the General Assembly issued Resolution 217 (III), International Bill of Human Rights, which contained the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As we have noted earlier, whereas the League’s Covenants had been largely silent on issues of human rights, the UN Charter explicitly embedded a range of human rights provisions, such as that contained in Article 55 (c). The Charter calls upon the United Nations to promote “universal respect for, and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.” The 1948 Resolution was endorsed by 48 of the then 58 member states. The significance of this Resolution cannot be overstated. It contributed to a major strengthening of the legal framework underpinning the observance of human rights at the global level and led to the negotiation of a wide range of international instruments addressing multiple dimensions of the human rights agenda, including on the status of refugees, genocide, the rights of women, slavery, torture, and several others. It led also to the 1966 adoption by the General Assembly of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenants on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see also Chapter 11).

While the General Assembly’s promotion of human rights is, without doubt, one of the most important areas of achievement, the Assembly also played a critical role in the process of decolonization. The UN Charter recognized explicitly the principle of the self-determination of peoples (Article 1(2)) and it was left to the General Assembly to identify territories that were non-self-governing or trust territories under League of Nations mandate. In this respect, the General Assembly had, as early as 1946, identified 74 non-self-governing territories (mainly colonies) belonging to the following UN member states: Australia, Belgium, Denmark, France, Netherlands, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Spanish and Portuguese colonies were added to this list in 1960. The challenge for the General Assembly was how to encourage the implementation of the principle of self-determination against the background of, at times, strong resistance from some members to even recognize that such territories were indeed colonies. For instance, for many years Spain and Portugal argued that territories under their control were “overseas provinces” (e.g., Angola, Sao Tome) and that as such they were subject to the protections embedded in Article 2(7), where the Charter proscribes the UN from “interven[ing] in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state.” A similar case was made by France in respect of Algeria and some of its other colonies.

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to go into a detailed description of the role played by the General Assembly in the process of decolonization, but suffice it to say that various General Assembly Resolutions, many of them pressing colonial powers to establish clear timetables for the granting of independence to their dependent territories, and firmly restating the legitimacy of peoples’ aspirations for independence, did much to strengthen the credibility of various grassroots political movements aimed at securing independence in various corners of the world. This resulted in a rapid increase in UN membership; by 1969, the United Nations had 126 members with the vast majority of the new entrants being former colonies, particularly in Africa.

The various General Assembly declarations touching upon the theme of human rights and its subsequent efforts to assist in the codification of the associated international law are a very good example of a larger body of work where the Assembly has sought to codify a series of norms pertaining to the behavior of states. The list of norms developed on various themes is long and includes a broad range of subjects, such as the peaceful uses of outer space, the environment and management of the global commons, the Law of the Sea, terrorism, peaceful coexistence of religions and cultures, the elimination of violence against women, elaborations on the importance of peaceful international dispute resolution, the essential elements of democracy, among a vast range of other progressive and humanitarian issues. While some of these initiatives have foundered in terms of implementation because of the absence of adequate enforcement mechanisms and/or the unwillingness of states sometimes to take seriously their commitments to resolutions that they themselves have supported through their representatives in the General Assembly, one must nevertheless recognize that the Assembly has played a useful catalytic role in helping to identify important core principles to guide the behavior of states, akin to the development of much needed Codes of Conduct.

In parallel to these important resolutions addressing issues of global concern, there were also attempts during the first decade to improve the working of the UN against the background of the distortions introduced by the repeated exercise of the veto by the Soviet Union. In this regard, Resolution 377 (V), also known as the “Uniting for Peace” Resolution, attempted to empower the General Assembly with the ability to act when the Security Council’s decision-making machinery had come to a standstill because of the exercise of the veto (in this case, that of the Soviet Union) and there were major issues of peace and security at play. In other words, the General Assembly made an explicit attempt to enter into the power vacuum created by a Security Council that was paralyzed. In particular, the Resolution resolves that

if the Security Council, because of lack of unanimity of the permanent members, fails to exercise its primary responsibilities for the maintenance of international peace and security in any case where there appears to be a threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression, the General Assembly shall consider the matter immediately with a view to making appropriate recommendations to Members for collective measures, including in the case of a breach of the peace or act of aggression, the use of armed force when necessary, to maintain or restore international peace and security.Footnote 9

Additionally, the UN Charter contains as a primary objective the furtherance of the economic and social development of peoples. The Preamble refers to “the promotion of the economic and social advancement of all peoples” as an important objective of the international community. The General Assembly’s record in this area is, in our estimation, considerably more mixed than its achievements in the area of human rights. The Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) was intended to play the central role in the implementation of these objectives and strengthened the link between the United Nations and its specialized agencies. ECOSOC’s beginnings were relatively auspicious, leading to the creation in 1947 of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). This set in motion several global rounds of trade liberalization, which contributed to a significant expansion of international trade and to a boost in economic growth for the global economy. The last of these, the Uruguay Round, eventually led in 1995 to the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO).

There seems to be general agreement, however, that by the turn of the century ECOSOC’s role in the area of social and economic development was much diminished. Several factors appear to have contributed to this. First, many of the specialized agencies began operating with a considerable degree of independence. For instance, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (created in 1944 at the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire) were founded with governing structures based on weighted voting, enabling the larger UN members to influence issues of economic development through their participation in the Boards of these organizations, leading to what became known, sometimes disparagingly, as the “Washington Consensus.” The fact that both the IMF and the World Bank had complete financial autonomy sharply weakened the link with the United Nations and thus with ECOSOC. By the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, the World Bank and particularly the IMF had decades of experience in crisis management, and in the promotion of policies intended to tackle poverty and to encourage better economic management. Not surprisingly, both organizations played a major role in addressing the impact of the crisis, with ECOSOC very much on the sidelines, both conceptually and operationally.

The second factor for the loss of ground by ECOSOC in the economic development space was the emergence of a large number of UN conferences convened by the General Assembly and with the extensive participation of civil society organizations on a range of global issues including population (1994), the environment (1992, 2012), social issues (1995), women (1995), and human rights (1993), which shifted the locus of debate beyond ECOSOC itself. ECOSOC credibility and legitimacy and its ability to occupy a significant position in the economic and development space may have been undermined by the fact that, like the General Assembly, it operates on the basis of a one-country-one-vote system. This in practice has meant that small developing countries had an outsize influence, prompting the larger members to channel their concerns through the WB and the IMF where they had in practice much greater influence. The presence of a large contingent of small developing countries representing a significant proportion of the world’s population in the General Assembly did also at times lead to polarization over the priorities of economic development between those defending global economic interests and those calling for more social and economic justice. An example of this are the debates that took place leading to General Assembly Resolutions on the “New International Economic Order,” which never took off in any operationally meaningful way, and it is probably accurate to say were largely ignored by the leaderships of the IMF and the World Bank. Not surprisingly, with the empowerment of smaller states within the General Assembly, the principle of sovereign equality has become deeply entrenched.

An interesting indicator of this phenomenon is provided by the assessed contribution to the budget of the lowest-income UN members, which was set at 0.04 percent in 1946 but had been reduced to 0.001 percent by the 1990s, or 40 times less. Furthermore, Switzerland’s contribution to the budget (1.151 percent) exceeds the cumulative contributions of the 120 countries with the smallest assessed shares. Indeed, the cumulative contribution of the 129 members with the lowest assessed shares, which is the minimum number of countries required for a two-thirds majority, is 1.633 percent. This is only slightly higher than the contribution of Turkey (1.371 percent) and lower than the contribution of Spain, the country with the next highest contribution (2.146 percent). A body organized on the basis of a principle that equates the voting power of China with a population of close to 1.4 billion people with that of Nauru having a population of about 13,000 (or over 106,000 times less) was fated to be less effective, and this distortion manifested itself in a number of ways. First and foremost, given the powers granted to the Assembly by the Charter over budgetary matters, is the perverse way that budget discussions, practices, and procedures evolved over time (discussed in detail in Chapter 12).

Another factor in the marginalization of the General Assembly stems from the nonbinding nature of Assembly resolutions, which by 2018 exceeded 18,000; the vast majority of them with no tangible operational repercussions on the ground. It is thus difficult to disagree with statements such as

[a]lthough the Security Council regained prominence after 1990 as a forum for managing international conflict, the General Assembly’s inability to break with its mind-numbing routine of debating and adopting resolutions (often multiple resolutions) on the same long list of topics contributes greatly to its continued obscurity… . Today it is overshadowed even within the UN not only by the more active Security Council but also by the series of UN global conferences and summits on particular issues.Footnote 10

Moving to a System of Weighted Voting

Amending the UN Charter to introduce a system of weighted voting has been the subject of extensive discussions over the years. It figured prominently in Clark and Sohn’s World Peace through World Law, where they presented detailed proposals on how to distribute the voting power among its members, and has been the subject of extensive research since then. We present a proposal in this chapter and comment on the challenges of devising a sensible system of representation. The motivation is not purely to create a voting structure that more closely resembles what currently exists at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which have operated on the basis of weighted voting since 1944 and, therefore, more clearly represented members’ economic and political power. It is actually principally about empowering the General Assembly to discharge more effectively the responsibilities given to it by Article 10 under the Charter, which grant it fairly wide discretion to discuss and make recommendations on a wide array of issues. Although Article 12 specifically gives the Security Council jurisdiction over interstate disputes and matters of international peace and security, the General Assembly can play, and has at times played, a role on such issues, particularly when the Security Council has been blocked or unable to act because of the exercise of the veto. (See for instance, the discussion above on the “Uniting for Peace” General Assembly Resolution and the factors that prompted it.) In such instances, an Assembly with a voice that more fairly represented the relative size of its members could speak with a greater measure of credibility that has generally been lacking under the one-country-one-vote system. In time, a reconstituted Assembly could be given the power to issue resolutions that are binding on its members and carry the force of international law. Expanding the powers of the General Assembly by turning it into a budding world legislature – the global equivalent of the European Parliament, with a more narrowly defined set of prerogatives and substantive jurisdiction – will never happen unless countries feel that there is broad correspondence between the size of the country and its voting power. But the issue goes well beyond redressing what has been perceived as a quaint (not to say unfair, given that the major powers in 1945 actually wanted it this way) system of representation. In fact, it overwhelmingly has to do with creating a body to occupy at least part of the space in the power vacuum that exists today to deal with urgent global problems for which we do not have the problem-solving mechanisms and institutions to address them.

In the paragraphs that follow we will present several options for a system of weighted voting. We agree with Schwartzberg that such a system should be based on a set of valid principles and objective criteria, applied to all members in an even-handed way. It should also be flexible enough to allow for evolution over time, to reflect changes in the data underpinning the indicators. It goes without saying that it should deliver a set of weights that is perceived by members as being realistic and fair.

A Modified Schwartzberg Proposal

Schwartzberg has put forward a proposal that uses three variables to arrive at a set of weights for membership in the General Assembly.Footnote 11 Each of these variables tries to capture some key principle, seen to be central to the creation of an equitable system of weighted voting. In particular, population size, to reflect each member’s accumulated demographic history and the idea that countries with larger populations represent a larger cross-section of humanity. The size of the member’s economy is a second variable, on the grounds that it is the driving factor determining the size of each country’s absolute contribution to the United Nations’ budget. While, as noted in Chapter 12 presenting a new funding mechanism, each country contributes a fixed share of their gross national income (GNI), their financial contributions differ markedly and clearly larger countries have a correspondingly larger impact on UN operations. Schwartzberg chooses to label this second variable “contributions to the UN budget” but this is a purely semantic distinction, since these contributions are exclusively dependent on a member’s GNI. The third variable is intended to capture the “legal/sovereign equality of nations principle, according to which all nations are counted equally.” All factors are weighted equally and are calculated, respectively, as percentages of the total population of all 193 members, their share of world GNI and their current voting power in the General Assembly, meaning that each country is allocated a 0.5181 percent share (e.g., 1/193). We will discuss this latter principle later in this section and examine its ramifications. Table 4.1 presents the results of applying this methodology, with updated data for all the variables but with an important modification. We believe this modification is justified on methodological grounds, and also to allay potential concerns on the part of many countries, particularly in the developing world, that the formula is not biased against them by the choice of metric used to assess economic size. Whereas Schwartzberg uses GNI at market prices, we use the weighted average (with equal weights) of gross domestic product (GDP) at market prices and GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) rates.Footnote 12

| Scenarios | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Assessed share1 | Population2 in %: P | GDP share3 in %: C | Membership share4 in %: M | I: W share5 in % | II: W share6 in % |

| Top 20 contributors | ||||||

| USA | 22.000 | 4.350 | 19.981 | 0.5181 | 8.283 | 8.956 |

| China | 12.005 | 18.515 | 16.947 | 0.5181 | 11.993 | 10.346 |

| Japan | 8.564 | 1.693 | 5.238 | 0.5181 | 2.483 | 3.592 |

| Germany | 6.090 | 1.104 | 3.990 | 0.5181 | 1.871 | 2.571 |

| United Kingdom | 4.567 | 0.882 | 2.817 | 0.5181 | 1.406 | 1.989 |

| France | 4.427 | 0.896 | 2.765 | 0.5181 | 1.393 | 1.947 |

| Italy | 3.307 | 0.809 | 2.142 | 0.5181 | 1.156 | 1.545 |

| Brazil | 2.948 | 2.795 | 2.588 | 0.5181 | 1.967 | 2.087 |

| Canada | 2.734 | 0.490 | 1.748 | 0.5181 | 0.919 | 1.247 |

| Russian Federation | 2.405 | 1.930 | 2.592 | 0.5181 | 1.680 | 1.618 |

| Republic of Korea | 2.267 | 0.329 | 1.775 | 0.5181 | 0.993 | 1.157 |

| Australia | 2.210 | 0.687 | 1.331 | 0.5181 | 0.726 | 1.019 |

| Spain | 2.146 | 0.622 | 1.534 | 0.5181 | 0.891 | 1.095 |

| Turkey | 1.371 | 1.078 | 1.406 | 0.5181 | 1.001 | 0.989 |

| Netherlands | 1.356 | 0.229 | 0.889 | 0.5181 | 0.545 | 0.701 |

| Mexico | 1.292 | 1.725 | 1.704 | 0.5181 | 1.316 | 1.178 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1.172 | 0.440 | 1.137 | 0.5181 | 0.698 | 0.710 |

| Switzerland | 1.151 | 0.113 | 0.636 | 0.5181 | 0.423 | 0.594 |

| Argentina | 0.915 | 0.591 | 0.769 | 0.5181 | 0.626 | 0.675 |

| Sweden | 0.906 | 0.134 | 0.545 | 0.5181 | 0.399 | 0.520 |

| Other countries | ||||||

| India | 0.834 | 17.885 | 5.404 | 0.5181 | 7.936 | 6.412 |

| Poland | 0.802 | 0.507 | 0.778 | 0.5181 | 0.601 | 0.609 |

| Indonesia | 0.543 | 3.526 | 1.932 | 0.5181 | 1.992 | 1.529 |

| Iran | 0.398 | 1.084 | 0.929 | 0.5181 | 0.844 | 0.667 |

| South Africa | 0.272 | 0.757 | 0.525 | 0.5181 | 0.600 | 0.516 |

| Nigeria | 0.250 | 2.549 | 0.683 | 0.5181 | 1.250 | 1.106 |

| Egypt | 0.186 | 1.303 | 0.627 | 0.5181 | 0.816 | 0.669 |

| Pakistan | 0.115 | 2.631 | 0.614 | 0.5181 | 1.254 | 1.088 |

| Lesotho | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.5181 | 0.184 | 0.183 |

| Liberia | 0.001 | 0.063 | 0.004 | 0.5181 | 0.195 | 0.194 |

1. Assessed budget contributions for the period 2019–2021 as determined by the General Assembly.

2. P is each country’s population share in the total population of all 193 UN members, 2017.

3. C is calculated as the weighted average of a country’s GDP share at market prices and GDP at PPP, for all 193 UN members, using 2017 numbers.

4. M is current voting power in the General Assembly (1/193), in percent.

5. W = (P+C+M)/3.

6. Based on 2019–2021 assessed budget shares.

In particular, we use the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook database for both GDP metrics for 2017, as opposed to 2009 in the Schwartzberg proposal. Two scenarios are presented in the Table 4.1. In Scenario I, the size of the economy variable is set as a percentage of each country’s share in world GDP, as calculated per the above method. So, for China for instance, this is set at 16.947 percent. In Scenario II, the size of the economy variable is captured by the actual assessed contribution rates established by the General Assembly for the period 2019–2021. This scenario is useful for comparison purposes, in the event that members did not accept to have contribution rates equal to the same fixed proportion of their GDP (as in Scenario I) and the current ad hoc arrangements prevailed which, as noted in Chapter 12, involve measures of GNI and a multiplicity of other factors, such as the burden of external debt, and so on. The table presents data for 30 countries; the top 20 contributors, which account for 83.83 percent of the total assessed budget (and a larger share if one were to include voluntary contributions) and several others deemed to be of interest, including a few small members for comparison purposes. In Scenario I, which embodies a new funding mechanism for the budget, the ten largest voting shares in the General Assembly are held by China (11.993 percent), the United States (8.283), India (7.936), Japan (2.483), Indonesia (1.992), Brazil (1.967), Germany (1.871), Russia (1.680), the United Kingdom (1.406), and France (1.393). Small countries such as Kiribati, Lesotho, and Liberia, all of which at present enjoy the lowest assessed contribution rate to the budget of 0.001 percent, have voting shares of 0.173, 0.184 and 0.195 percent, respectively. Table A1 in the Annex presents the voting shares under Scenario I for all 193 UN members. The results in Scenario II show somewhat smaller voting shares for China, India, Indonesia, and Russia and somewhat bigger shares for the United States, Japan, Germany, Brazil, the United Kingdom, and France. The voting power of the smallest countries is virtually unchanged, given their very small contributions to the budget.

It is interesting to note that in Scenario I the voting shares of Russia, the United Kingdom, and France, the three veto-wielding members of the Security Council other than China and the United States, are the 8th, 9th, and 10th largest in the General Assembly and are all under 2 percent.Footnote 13 Perhaps few things express more eloquently the irrationality of the veto power in 2018 than these numbers. A credible mechanism to allocate voting power in the General Assembly on the basis of sensible principles may run up against a perceived diminished stature in the world of these three countries in particular, with respect to the positions occupied in 1945 at the San Francisco Conference. In 2017, for example, Russia’s GDP was roughly equivalent to the size of Spanish GDP, which itself is less than 8 percent of the size of the US economy. Of course, the solution to this problem is not to confer the power of the veto to India, Japan, Indonesia, Brazil, and Germany, but to do away with the veto altogether, as we argue in Chapter 7 on the creation of the Executive Council. The voting privileges within the Security Council remain an unreasonable anachronism.

The merits of the above proposal notwithstanding, it is not wholly exempt from criticisms. An argument can be made that it introduces incentives whereby UN members gain voting power by boosting economic and population growth above the global average. If governments are intent on the pursuit of high-quality economic growth that might be mirrored in a sustainable environment and improved income distribution metrics, as opposed to simply higher GDP, or stabilizing or even slowing down population growth, their voting power in the General Assembly could be eroded over time. We feel these concerns are legitimate and would thus consider the updated Schwartzberg proposals presented above as a major improvement over the one-country-one-vote system, but as a transitional arrangement, pending the arrival of better economic metrics, which more intelligently capture measures of human welfare and sustainability.

Furthermore, the above arguments notwithstanding, it is also possible to have some misgivings about the third factor in the Schwartzberg proposal, based on the “sovereign equality of nations” principle which attributes a one-third weight to each country’s voting share in today’s General Assembly based on the practice of one-country-one-vote. At a purely methodological level, the effect of introducing this third factor is to increase the voting shares of the smaller countries and reduce the voting shares of the larger ones. Viewed as a political and transitional factor, introduced to entice the smaller countries to vote for an amendment to the UN Charter that would move the General Assembly to a system of weighted voting, it could make good sense. It would signal to members that voting shares in the General Assembly are not purely based on relative size factors – such as population and the size of the economy as embedded in the GNI/GDP – but include an additional factor that confers some value to the concept of nationhood and the importance of diversity, regardless of the size.

One could also argue that such proposal could be sold to member countries as delivering a system that builds upon the existing one-country-one-vote structure, in operation since 1945 and that would be part of a comprehensive set of reforms that would deliver multiple other benefits to members, including the smaller countries, as noted elsewhere in this volume (e.g., the introduction of a more genuine international rule of law and a system of collective security that would allow a redirection of budgetary resources to more productive ends).

But it is also possible to argue the opposite case. The one-country-one-vote principle could be considered undemocratic, although it has at times given a stronger voice to diverse states and peoples who might not normally be heard or considered influential, arguably to the benefit of the whole organization. However, its application (coupled with the veto power in the Security Council) has turned the United Nations into a less effective organization and the General Assembly, in particular, into a body given too often to political posturing and to the issuing of resolutions that carry the weight of nonbinding recommendations. They do not yet have adequate international democratic legitimacy, as they give the citizens of large countries such as China and India a tiny fraction of the voice given to the citizens of microstates. One could also argue that, other things being equal, it would discourage countries from granting independence to territories with ethnically distinct populations, or from political union as they would lose out voting share. Czechoslovakia doubled its General Assembly voting power when it split into Slovakia and the Czech Republic in 1993.

Embedding – even with a one-third share – the one-country-one-vote practice into a new system of weighted voting might also have other undesirable long-term implications. In the US senate, the state of Wyoming (with a population of slightly more than half a million) has the same number of senators (2) as the state of California, with more than 39 million people. When the US Senate votes to approve an international treaty, for instance, as it did in 1945 when it approved the UN Charter, the weight given to a citizen of Wyoming is 70 times larger than that given to a citizen of California. So, the principle of even-handedness of treatment or the application of the same criteria to all members is considerably strained in this version of the Schwartzberg proposal.

One key argument put forth by those who think that significant reforms are needed at the United Nations is that, in an interdependent world in which the meaning of national borders is being eroded through the forces of globalization, we need to strengthen our mechanisms for international cooperation. We need to join forces and work across national boundaries to address major global problems that take scant notice of notions of nationhood and sovereignty. To address the challenges of climate change, for instance, we need to think and act like world citizens, not in the traditional ways that put the national interest above everything else and which, it must be said, have been largely responsible for our failure to take meaningful actions to mitigate its impacts.

The challenge, in designing a proposal for weighted voting in the General Assembly, is one of balance. The principle of “sovereign equality” has in this context generally been damaging to the United Nations’ credibility. One can argue that individual humans – regardless of their nationality or other distinguishing feature such as ethnic origin, gender and so on – should be regarded as equal in terms of their rights and responsibilities, and that we should develop global governance systems that are based on the principle of equality of opportunity, the fundamental principle of the inalienable dignity of the individual human person, and the essential unity of the human race. However, a demographic measure, by itself, could give the most populous countries a de facto power of veto over major decisions of the General Assembly that require a two-thirds majority.

Using a measure of the weight of the economy such as the share in world GDP can seem logical in terms of relative contributions to the UN budget (who pays the bills calls the tune), but it could also be argued that giving the rich and powerful a bigger voice than the poor because they have more money is fundamentally unjust.

The sovereign equality principle (based in part on the principle of self-determination of peoples), while it may seem antidemocratic, acknowledges that the great diversity of nations in size, culture, forms of governance, and experience within the global system needs to be reflected in, and contribute to, global deliberative processes, to enrich them in a way that purely quantitative representation cannot. Minority perspectives can shed additional light on issues that might not at first be apparent to the majority, and decision-making can be strengthened as a result.Footnote 14 Our proposal aims at a just balance between these different perspectives.

An Updated Clark and Sohn Proposal

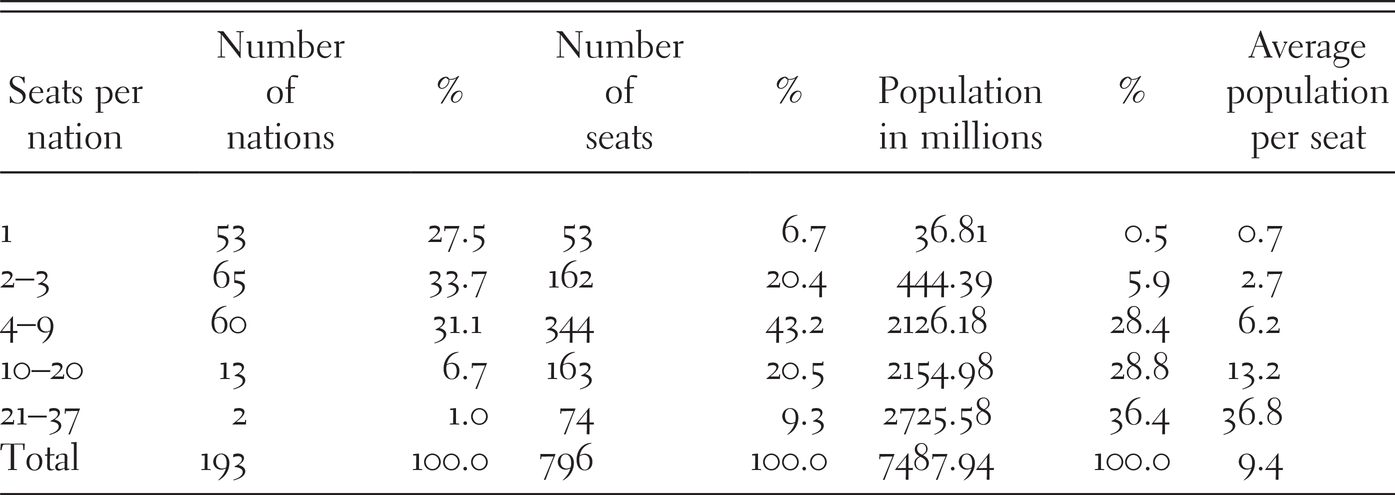

In World Peace through World Law (1966) Clark and Sohn made a strong case for the introduction of a system of weighted voting in the General Assembly. Clark, in particular, as we saw in Chapter 2, had played an active part in the debates leading to the creation of the United Nations and advocated for a stronger role for the General Assembly, seeing it as the seed of a global legislature with powers in a narrowly defined set of areas, mainly to do with peace and security questions. In framing their proposals and suggesting a particular set of voting shares they faced a number of challenges that are no longer present today. In 1960 there were 99 United Nations members that had joined the organization as fully independent states, but there were close to 100 million people living in non-self-governing and trust territories that, in their view, should also be represented. They also would have faced onerous data collection problems, both as regards coverage across countries and in terms of the quality of the sparse information available, for instance on internationally comparable measures of national income, particularly for developing countries. In setting the criteria for determining voting shares they considered a number of variables but felt that “the introduction of any such other factors would raise so many complications and involve such uncertain and invidious distinctions that is it wiser to hold to the less elaborate formula herein proposed,”Footnote 15 which was to link voting shares to population but in a way that created population groupings (e.g., the four largest nations, the next eight largest nations, the next twenty largest nations, and so on) and allocated the same voting share to all countries within each one of these groupings. They did this in a way that allocated proportionally fewer shares to the most populous states, an early application of the principle of digressive proportionality. In their discussion of voting shares Clark and Sohn laid out some principles to guide the determination of voting shares, including that every nation should be entitled to some representation no matter how small, that there should be a reasonable upper limit on the voting share of the most populous countries and that no factors other than population should be considered. Additionally, it was important to have a General Assembly that would not be very large and unwieldy. So, in their proposed allocation, the four states with the highest populations – China, India, the Soviet Union, and the United States – each would be entitled to 30 representatives in a Chamber comprising 568 members, equivalent to a 5.282 percent voting share each. Clark and Sohn’s application of the principle of digressive proportionality meant that the 12 largest nations with a 1960 population of 2,186 million people would be allocated 240 representatives, while the remaining 87 nations with a population of 891 million would be entitled to 311 representatives. Clark and Sohn spent considerably more time discussing how representatives to this body would be chosen, what would be the length of service and the relevant areas of legislative authority. Table 4.2 presents an updated Clark and Sohn proposal for the current 193 members that reflects the spirit of their original allocation. It is possible to generate variants of this proposal that distribute voting shares in a way that is somewhat more generous with countries with high populations.

Table 4.2 Updated General Assembly voting shares under modified Schwartzberg proposal and updated Clark proposal

| Country | Modified Schwartzberg proposal1 | Updated Clark proposal2 |

|---|---|---|

| Top 20 contributors | ||

| United States of America | 8.283 | 5.277 |

| China | 11.993 | 5.277 |

| Japan | 2.483 | 1.319 |

| Germany | 1.871 | 1.319 |

| United Kingdom | 1.406 | 0.660 |

| France | 1.393 | 0.660 |

| Italy | 1.156 | 0.660 |

| Brazil | 1.967 | 2.639 |

| Canada | 0.919 | 0.528 |

| Russian Federation | 1.680 | 1.319 |

| Republic of Korea | 0.993 | 0.660 |

| Australia | 0.726 | 0.528 |

| Spain | 0.891 | 0.660 |

| Turkey | 1.001 | 1.319 |

| Netherlands | 0.545 | 0.396 |

| Mexico | 1.316 | 1.319 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.698 | 0.528 |

| Switzerland | 0.423 | 0.264 |

| Argentina | 0.626 | 0.660 |

| Sweden | 0.399 | 0.396 |

| Other countries | ||

| India | 7.936 | 5.277 |

| Poland | 0.601 | 0.528 |

| Indonesia | 1.992 | 2.639 |

| Iran | 0.844 | 1.319 |

| South Africa | 0.600 | 0.660 |

| Nigeria | 1.250 | 2.639 |

| Egypt | 0.816 | 1.319 |

| Pakistan | 1.254 | 2.639 |

| Lesotho | 0.184 | 0.264 |

| Liberia | 0.195 | 0.264 |

1. From Table 4.1.

2. Allocates voting shares in relation to population using thresholds set at 300, 160, 70, 40, 20, 10, and 1 million people.

In light of the above discussion and mindful of the various limitations identified for each of the two proposals, we would like to side with the modified updated Schwartzberg proposal. On balance, we think this is the one that better captures the multiple factors that must be considered in coming up with a system of weighted voting in the General Assembly that is fair and transparent, striking a broadly acceptable balance between giving larger countries greater voice, while ensuring that smaller nations maintain an adequate level of representation. Although both proposals – Schwartzberg’s and Clark and Sohn’s – are a major improvement over the current system, it is, of course, possible to imagine alternative methodologies to come up with a set of country weights. One should, in any case, see these proposals as transitional arrangements, and as more sensible options to the current one-country-one-vote system, but likely to evolve in time as better data become available.

The Box at the end of this chapter presents Articles 9, 10 and 11 of the current UN Charter on the General Assembly composition, functions and powers. By way of illustration we also present amended versions of the same Articles to be consistent with the updated system of weighted voting proposed here and the enhanced functions and powers of the General Assembly, in light of other proposals made in subsequent chapters. These proposals and revisions concern only the peace and security functions in the UN Charter. A new but similar article will be needed to define the legislative functions and powers of the General Assembly concerning the management of the global environment.

Selection of Members

We propose a substantial revision of the powers, composition and method of voting of the General Assembly, as initially laid out in the revised Articles 9–22 of the UN Charter. In the first instance, the General Assembly would be given some powers to legislate with direct effect on member states, mainly in the areas of security, maintenance of peace and management of the global environment, with other issues (e.g., surveillance of global financial policies) remaining under the purview of the relevant specialized UN agencies and other international bodies. The General Assembly would take on further legislative powers in progressive steps subject to review of such powers every five years by its members. Powers delegated to the General Assembly would be explicitly laid out and enumerated in the revised Charter which would also contain – in a revised Article 2 on Purposes and Principles – clarity as to what powers would remain vested with member states to protect national autonomy and would not be delegated to the Assembly, following, for example, the EU model of subsidiarity (and proportionality), and/or a clarification of the proper division of powers as seen in systems characterized by federal forms of government. The General Assembly would retain its considerable powers of nonbinding recommendation in any areas deemed to have an impact on the welfare of the world’s people.

In respect of the manner of selection of the Assembly’s representatives we propose the gradual introduction of full popular vote, in three separate stages. In the first stage – lasting eight years or two four-year terms of the General Assembly – representatives would be chosen by their respective national legislatures or, in their absence, according to procedures within other duly constituted governance structures. In the second stage, at least half of the deputies would be chosen by popular vote within a given country; this stage would also last eight years. Finally, in the third stage all deputies would be chosen by popular national vote. Such elections would have to be certified by an impartial international elections board, according to international standards of free and fair elections, before the representative could be confirmed for service in the Assembly. While it may seem a stretch that all countries of the world would be expected to eventually elect their international representatives by popular vote, it has been noted that, in parallel with the wide array of statements emanating from UN bodies affirming the importance of democracy (see those mentioned in Chapter 5, below), as of the 1990s on the international plane, an emerging global “consensus” has been observed that democratic societies might be the “sole feasible social structure.”Footnote 16 As regards voting procedures within the General Assembly, decisions would be made by a majority of representatives present and voting, with particularly sensitive issues requiring potentially larger majorities and including, in some cases, at least two-thirds of the representatives of the 19 most populous nations.

Current UN Charter

The General Assembly Composition

Article 9

1. The General Assembly shall consist of all the Members of the United Nations.

2. Each Member shall have not more than five representatives in the General Assembly.

Functions and Powers

Article 10

The General Assembly may discuss any questions or any matters within the scope of the present Charter or relating to the powers and functions of any organs provided for in the present Charter, and, except as provided in Article 12, may make recommendations to the Members of the United Nations or to the Security Council or to both on any such questions or matters.

Article 11

1. The General Assembly may consider the general principles of cooperation in the maintenance of international peace and security, including the principles governing disarmament and the regulation of armaments, and may make recommendations with regard to such principles to the Members or to the Security Council or to both.

2. The General Assembly may discuss any questions relating to the maintenance of international peace and security brought before it by any Member of the United Nations, or by the Security Council, or by a state which is not a Member of the United Nations in accordance with Article 35, paragraph 2, and, except as provided in Article 12, may make recommendations with regard to any such questions to the state or states concerned or to the Security Council or to both. Any such question on which action is necessary shall be referred to the Security Council by the General Assembly either before or after discussion.

3. The General Assembly may call the attention of the Security Council to situations which are likely to endanger international peace and security.

4. The powers of the General Assembly set forth in this Article shall not limit the general scope of Article 10.

Revised Articles 9, 10, and 11Footnote 17

The General Assembly Composition

Article 9

1. The General Assembly shall consist of Representatives from all the member nations.Footnote 18

2. The number of representatives in the General Assembly shall be directly proportional to each member nation’s voting share. The voting share shall be determined as the arithmetic average of each member’s world population share, world GDP share, and a membership share which shall be equal for all members.

3. The apportionment of Representatives pursuant to the foregoing formula shall be made by the General Assembly upon the basis of world censuses and GDP estimates as compiled and published in the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. The first census shall be taken within ten years after the coming into force of this revised Charter and subsequent censuses shall be taken in every tenth year thereafter, in such manner as the Assembly shall direct. The Assembly shall make a reapportionment of the Representatives within two years after each such census.

4. Until the first apportionment of Representatives shall be made by the General Assembly upon the basis of the first world census, the apportionment of Representatives in the Assembly shall be based on the latest and most authoritative figures compiled by the United Nations Population Division.

5. Representatives shall be chosen for terms of four years, such terms to begin at noon on the Third Tuesday of September in every fourth year.

6. For the first two terms after the coming into force of this revised Charter, the Representatives from each member nation shall be chosen by its national legislature, or, in the absence of such a body, by the government through a process of consultation to ensure broad representation, except to the extent that such legislature may prescribe the election of the representatives by popular vote. For the next two terms, not less than half of the representatives from each member nation shall be elected by popular vote and the remainder shall be chosen by its national legislature, unless such legislature shall prescribe that all or part of such remainder shall also be elected by popular vote; provided that any member nation entitled to only one Representative during this two-term period may choose its Representative either through its national legislature or by popular vote as such legislature shall determine. Beginning with the fifth term, all the Representatives of each member nation shall be elected by popular vote. The General Assembly may, however, by a two-thirds vote of all the Representatives in the Assembly, whether or not present or voting, postpone for not more than four years the coming into effect of the requirement that not less than half of the Representatives shall be elected by popular vote; and the Assembly may also by a like majority postpone for not more than four years the requirement that all the Representatives shall be elected by popular vote. In all elections by popular vote held under this paragraph, all persons shall be entitled to vote who are qualified to vote for the members of the most numerous branch of the national legislatures of the respective nations, with the results being subject to international electoral certification.

7. Any vacancy among the Representatives of any member nation shall be filled in such manner as the national legislature of such member nation may determine. A Representative chosen to fill a vacancy shall hold office for the remainder of the term of his predecessor.

8. The Representatives shall receive reasonable compensation, to be fixed by the General Assembly and to be paid out of the funds of the United Nations.

9. There will be a limitation of three four-year terms on the length of service of Representatives.

Functions and Powers

Article 10

The General Assembly shall have the power:

a. to enact legislation binding upon member nations and all the peoples thereof, within the definite fields and in accordance with the strictly limited authority hereinafter delegated;

b. to deal with disputes, situations, threats to the peace, breaches of the peace, acts of aggression and matters relating to management of the planetary environment, as hereinafter provided;

c. to make nonbinding recommendations to the member nations, as hereinafter provided;

d. to elect the members of other organs of the United Nations, as hereinafter provided;

e. to discuss, and to direct and control the policies and actions of the other organs and agencies of the United Nations, with the exception of the International Court of Justice; and

f. to discuss any questions or any matters within the scope of this revised Charter.

Article 11

1. The General Assembly shall have the primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security, and for ensuring compliance with this revised Charter and the laws and regulations enacted thereunder.

2. To this end the General Assembly shall have the following legislative powers:

a. to enact such laws and regulations as are authorized by Annex I of this revised Charter relating to universal, enforceable and comprehensive national disarmament, including the control of nuclear energy and the use of outer space;

b. to enact such laws and regulations as are authorized by Annex II of this revised Charter relating to the military forces necessary for the enforcement of universal and comprehensive national disarmament, for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace, for the suppression of acts of aggression and other breaches of the peace, and for ensuring compliance with this revised Charter and the laws and regulations enacted thereunder;

c. to enact appropriate laws defining the conditions and establishing the general rules for the application of the measures provided for in Chapter VII;

d. to enact appropriate laws, as needed, establishing what acts or omissions of individuals or private organizations within the following categories shall be deemed offenses against the United Nations: (1) acts or omissions of government officials of any nation which either themselves constitute or directly cause a threat of force, or the actual use of force by one nation against any other nation, except that no use of force in self-defense under the circumstances defined in Article 51 of this revised Charter shall be made such an offense; (2) acts or omissions of any government official or any other individual or any private organization which either themselves constitute or directly cause a serious violation of Annex I of this revised Charter or of any law or regulation enacted thereunder; (3) acts or omissions causing damage to the property of the United Nations or injuring any person in the service of the United Nations while engaged in the performance of official duties or on account of the performance of such duties; and (4) acts or omissions of any individual in the service of any organ or agency of the United Nations, including the United Nations International Peace Force, which in the judgment of the General Assembly are seriously detrimental to the purposes of the United Nations;

e. to enact appropriate laws:

(1) prescribing the penalties for such offense as are defined by the General Assembly pursuant to the foregoing subparagraph (d);

(2) providing for the apprehension of individuals accused of offenses which the Assembly has defined as sufficiently serious to require apprehension, such apprehension to be by the United Nations civil police provided for in Annex III or by national authorities pursuant to arrangements with the United Nations or by the joint action of both;

(3) establishing procedures for the trial of such individuals in the courts administered by the United Nations, provided for in Annex III; and

(4) providing adequate means for the enforcement of penalties.

3. No such law shall, however, relieve an individual from responsibility for any punishable offense by reason of the fact that such individual acted as head of state or as a member of a nation’s government. Nor shall any such laws relieve an individual from responsibility for any such offense on the ground that he has acted pursuant to an order of his government or of a superior, if, in the circumstances at the time, it was reasonably possible for him to refuse compliance with that order.

4. The member nations agree to accept and carry out the laws and regulations enacted by the General Assembly under paragraph 2 of this Article, and the decisions of the Assembly made under this revised Charter including the Annexes; provided, however, that any member nation shall have the right to contest the validity of any such law, regulation or decision by appeal to the International Court of Justice. Pending the judgment of the Court upon any such appeal, the contested law, regulation, or decision shall nevertheless be carried out, unless the Assembly or the Court shall make an order permitting noncompliance, in whole or in part, during the Court’s consideration of the appeal.

5. As soon as possible after the coming into force of this revised Charter, the Executive Council shall negotiate with any state that may not have become a member of the United Nations an agreement by which such state will agree to observe all the prohibitions and requirements of the disarmament plan contained in Annex I of this revised Charter, and to accept and carry out all the laws, regulations, and decisions made thereunder, and by which the United Nations will recognize the right of any such state and of its citizens to all the protection and remedies guaranteed by this revised Charter to member nations and their citizens with respect to the enforcement of Annex I and the laws, regulations, and decisions made thereunder. If a state refuses to make such an agreement, the Executive Council shall inform the General Assembly, which shall decide upon measures to be taken to ensure the carrying out of the disarmament plan in the territory of such state.

The assembly’s very existence would also help promote the peaceful resolution of international conflicts. Because elected delegates would represent individuals and society instead of states, they would not have to vote along national lines. Coalitions would likely form on other bases, such as world-view, political orientation, and interests. Compromises among such competing but nonmilitarized coalitions might eventually undermine reliance on the current war system, in which international decisions are still made by heavily armed nations that are poised to destroy one another. In due course, international relations might more closely resemble policymaking within the most democratic societies in the world.Footnote 1

The United Nations is not a world government, but it is our primary forum to discuss issues and risks of global significance in an increasingly interdependent world. Whether it is perceived as being imbued with a strong dose of democratic legitimacy matters a great deal for its effectiveness, credibility, and ability to become a problem-solving organization. For all of these reasons, and for those expressed below, we suggest the establishment of a significantly reformed General Assembly as explained in Chapter 4. Until such significant reforms are realized, in this chapter we also sketch out the possibility of an interim “World Parliamentary Assembly” that could serve as an advisory body to the General Assembly, acting as a type of “second chamber,” and greatly enhancing the legitimacy of the UN as a global decision-maker as soon as possible.

This is particularly important because the United Nations General Assembly itself on a number of occasions has expressed its unambiguous support for democratic forms of governance for its members. For instance, General Assembly Resolution 44/146 (1989) on

Enhancing the effectiveness of the principle of periodic and genuine elections [stressed] its conviction that periodic and genuine elections are a necessary and indispensable element of sustained efforts to protect the rights and interests of the governed and that, as a matter of practical experience, the right of everyone to take part in the government of his or her country is a crucial factor in the effective enjoyment by all of a wide range of other human rights and fundamental freedoms, embracing political, economic, social and cultural rights.Footnote 2

And General Assembly Resolution 55/2 (2000), one of the more substantive resolutions issued in recent decades, also known as the United Nations Millennium Declaration, states: “We consider certain fundamental values to be essential to international relations in the twenty-first century.” These include: freedom, equality, solidarity, tolerance, respect for nature, and that “democratic and participatory governance based on the will of the people best assures these rights.”Footnote 3 Clearly the United Nations voice in these important matters would carry considerably more weight if it were seen itself as being imbued by adequate levels of democratic legitimacy.

The idea of establishing a second chamber at the United Nations has existed since the organization’s inception. Grenville Clark and Louis Sohn wrestled with the issue as they worked on World Peace through World Law in the 1950s. While not actually recommending the creation of a bicameral UN, they stated: “We hold no dogmatic views on this difficult subject, the essential point being that there must be some radical, yet equitable, change in the present system of representation in the General Assembly as a basis for conferring upon the Assembly certain essential, although carefully limited, powers of legislation which it does not now possess.”Footnote 4 The idea is certainly older than the UN; the founders of the League of Nations for a time considered adding a people’s assembly as part of the League’s initial organizational structure.

One key motivation was to enhance the democratic character of the UN by establishing a firmer linkage between the organization and the peoples it was meant to serve. The preamble to the UN Charter starts with “We the peoples” and highlights our determination to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war” and to achieve other noble ends. But, in time, the General Assembly, which comes closest among the UN’s existing agencies to representing the will of the people, falls far short of this. The men and women who serve on the General Assembly are diplomats representing the executive branches of their respective governments and there is generally no meaningful, direct linkage between them and the people they are supposed to represent. In fact, in many countries, there is no linkage between the governments themselves and the people they rule over because they are not working democracies. In his open letter to the General Assembly of October 1947 Albert Einstein stated:

the method of representation at the United Nations should be considerably modified. The present method of selection by government appointment does not leave any real freedom to the appointee. Furthermore, selection by governments cannot give the peoples of the world the feeling of being fairly and proportionately represented. The moral authority of the United Nations would be considerably enhanced if the delegates were elected directly by the people. Were they responsible to an electorate, they would have much more freedom to follow their consciences. Thus we could hope for more statesmen and fewer diplomats.Footnote 5

In time, rather than bring a measure of democratic legitimacy to the General Assembly by providing for the direct election of its members – an innovation that would require amendments to the UN Charter, as outlined in Chapter 4 – proposals emerged that put forward the creation of a second chamber, a World Parliamentary Assembly (WPA), complementary to the General Assembly, which would continue to be the main locus of government-to-government interactions. The WPA would help bridge the democratic legitimacy gap that arises when an organization, through its actions (e.g., the drafting of Conventions, decisions to intervene or not on behalf of the international community in various conflicts, the actions of its various specialized agencies and related organizations) can affect in tangible ways people’s welfare, but those affected by these decisions have little input in how they are formulated, arrived at, and implemented, thereby creating a disconnection between citizens and the United Nations.

In Chapter 4 on the General Assembly we argued in favor of giving the General Assembly greater powers to legislate in a narrow set of areas, to empower it to actually begin to deliver on the main aspirations embedded in the UN Charter. We think that this idea would gain greater acceptance and better outcomes would be ensured if the UN moved, as quickly as possible, to establish interim mechanisms that also represent peoples more directly, not just governments and/or states. Governments’ main interest at the UN to date, by and large (either consciously or through the power of inertia), is the preservation of a system overly reliant on a too-narrow conception of the sovereign state. With the possible exception of the member states of the European Union, they are mainly motivated by the belief that “a nation-state cannot be subjected to, or made accountable for the decisions of any authority beyond itself.”Footnote 6 This may have been a convenient ideological foundation for the UN for the major powers in 1945 but it has increasingly turned into an absurdity – close to 200 sovereign states operating in an interdependent world increasingly in need of a global rule of law, but bound by a chaotic patchwork of different, at times contradictory, sets of rules.

Representing the interests of the global citizenry, a new WPA, advising the current UN General Assembly, could bring in a fresh global perspective on the broad array of unresolved problems that we currently confront. It would be in a stronger position to promote higher levels of international cooperation because its members would be called upon to see such problems through the lens of humanity’s better interests rather than narrow national considerations. The WPA also could be a much more effective catalyst for advancing the process of reform and transformation at the United Nations itself because, as we shall explain below, its members would have a much looser linkage with their respective governments and their specific national – as opposed to global – priorities. In the 2010 version of his original paper making the case for the establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, Heinrich notes that such a body could also play a role in reinforcing democratic tendencies in many corners of the world and foster “a new planetarian ethos by symbolizing the idea of the world as one community.”Footnote 7

Setting up a World Parliamentary Assembly

Article 22 of the UN Charter states: “The General Assembly may establish such subsidiary organs as it deems necessary for the performance of its functions.”Footnote 8 It is likely that the creation of a WPA would be seen in the spirit of the “important questions” identified in Article 18 of the Charter, which require a two-thirds majority of those members present and voting for approval, but would not require the approval of the permanent members of the Security Council. So, building public and governmental support for a General Assembly resolution putting in motion the establishment of a WPA would be the first step in what would likely be a multi-stakeholder process, involving wide consultations. However, this process will not start from zero. The creation of a WPA has already received strong endorsements from a number of major organizations and bodies. In 1993 the Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade recommended that “Canada support the development of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly.”Footnote 9 In 2005, with the support of the Committee for a Democratic UN – now known as Democracy without Borders – 108 Swiss Parliamentarians sent an open letter to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan calling for the establishment of a WPA.Footnote 10 That same year the Congress of the Liberal International followed suit by calling “on the member states of the United Nations to enter into deliberations on the establishment of a Parliamentary Assembly at the United Nations.”Footnote 11

Also in June 2005 (and again in July 2018) the European Parliament issued a resolution that called for “the establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA) within the UN system, which would increase the democratic profile and internal democratic process of the organisation and allow world civil society to be directly associated in the decision-making process,” also stating that “the Parliamentary Assembly should be vested with genuine rights of information, participation and control, and should be able to adopt recommendations directed at the UN General Assembly.”Footnote 12 These declarations were given further stimulus in 2007 with the establishment of the International Campaign for a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, an umbrella organization that, as of 2018, has brought together over 150 civil society groups and 1540 parliamentarians from 123 countries. It defines itself as:

a global network of parliamentarians, non-governmental organizations, scholars, and dedicated citizens that advocates democratic representation of the world’s citizens at the United Nations. A United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, UNPA, for the first time would give elected citizen representatives, not only states, a direct and influential role in global policy.Footnote 13

The World Federation of United Nations Associations issued a resolution at their World Congress on October 21, 2018, stating that it “supports steps towards the creation of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly” and that the UN “must address the democratic deficit within global decision-making processes” if it is to be successful “in the pursuit of creating a better world for all and ensuring that no one is left behind.”Footnote 14 A similar resolution was issued in May of 2016 by the Pan-African Parliament.Footnote 15