Introduction

In the last two decades, public management reforms, as international phenomena, have become serious subjects in the majority of developed and developing countries (Batley, Reference Batley2004; Burau and Fenton, Reference Burau and Fenton2009). It is essential to consider these reforms to respond to the economic, organizational and cultural changes and to evaluate the level of improvement in a government effectiveness and, to critique the costly public sector (Dunleavy and Hood, Reference Dunleavy and Hood1994; Elias Sarker, Reference Elias Sarker2006).

As a part of these reforms, a paradigm of public sector management has been known as new public management (NPM) (Hoyle, Reference Hoyle2011). The NPM was begun in the late 1980s in developed countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia and was improved after implementation in various countries over the years (Pollitt, Reference Pollitt1990; Burau and Fenton, Reference Burau and Fenton2009; Pollitt and Bouckaert, Reference Pollitt and Bouckaert2011; Keisu et al., Reference Keisu, Öhman and Enberg2016; Willis et al., Reference Willis, Toffoli, Henderson, Couzner, Hamilton, Verrall and Blackman2016) This reform was created as an answer to the differences found in the performance of public sector compared with the private sector, and due to the poor incentive structures that may led to weak performance in public sector (Pallott, Reference Pallott1999; Shaw, Reference Shaw2004).Therefore, policy makers and reformers want to apply such reforms to ensure that the public sector organizations become look like their private sector counterparts (Poole et al., Reference Poole, Mansfield and Gould‐Williams2006; Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, Reference Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff2015).

In addition, these reforms are described as normative conceptualizations of public administration which include several inter-related components such as decentralization, paying attention to the human resources, utilization of pay-for-performance, increasing autonomy of public managers, use of market mechanism, emphasizing on output control, disaggregation, increasing competition and innovation and emphasizing great discipline and well economical use of resources (Dunleavy and Hood, Reference Dunleavy and Hood1994; Hood, Reference Hood1995; Austin, Reference Austin2004; Sarker, Reference Sarker2005).

Although in many countries, the private health sector has more than 50% of the total resources related to the health sector (Kalimullah et al., Reference Kalimullah, Alam and Nour2012), it is reported to be faced with a market failure in the provision of health services (Buse and Walt, Reference Buse and Walt2000; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Brugha, Hanson and McPake2002). On the other hand, health sector, like public sector is faced with failure to provide health services for people. Therefore, it is necessary for health sectors to participate in both public and private sectors (Buse and Walt, Reference Buse and Walt2000; Soeters and Griffiths, Reference Soeters and Griffiths2003). To do so, policy makers and managers in the health sector, like those in the other sectors, try to use positives characteristics of NPM (Shaw, Reference Shaw2004).

In a majority of countries, NPM policies have been applied in health sector to attain different goals including decreasing health care expenditures, increasing efficiency and effectiveness, cost saving and improving the quality of public services (Simonet, Reference Simonet2008; Connell et al., Reference Connell, Fawcett, Meagher, Newman and Lawler2009; Acerete et al., Reference Acerete, Stafford and Stapleton2011). For example in the United Kingdom, provider/funder dichotomy was developed as a radical market-based mechanism (Simonet, Reference Simonet2008). In New Zealand, Singapore and some other countries, it is emphasized on the rule of law, market-based approaches and contract-like arrangements (Aucoin and Peter, Reference Aucoin and Peter1995; Elias Sarker, Reference Elias Sarker2006). Denmark and Norway also tried to improve the management practices and to privatize the publicly owned enterprises (Jensen, Reference Jensen1998; Guthrie et al., Reference Guthrie, Olson and Humphrey1999).

Since 1979, in Iran, like other countries, the health policy makers ratified and performed various laws to achieve ‘Health for All’ (Keisu et al., Reference Keisu, Öhman and Enberg2016). One of the most important transformations during this period was the merging of medical education in Ministry of Health and the formation of the ‘Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME)’ at the national level (Willis et al., Reference Willis, Toffoli, Henderson, Couzner, Hamilton, Verrall and Blackman2016). Another reform was the establishment of ‘medical sciences universities’ at the provincial level (Mehrdad, Reference Mehrdad2009).

At the district level, ‘town’ was accepted as an administrative standard for the development of health care units. In this level, a district’s health network includes the district health center (urban and rural health centers, health posts and health houses) and the district general hospital (Asadi-Lari et al., Reference Asadi-Lari, Sayyari, Akbari and Gray2004). In 2005, family physician program and universal health insurance were implemented in all Iranian rural areas and after seven years, in 2012, these programs were performed in some urban areas (Nasrollahpour Shirvani et al., Reference Nasrollahpour Shirvani, Ashrafian Amiri, Motlagh, Kabir, Maleki, Shabestani Monfared and Alizadeh2010), as well. However, similar to other countries, there are many problems in the public health sector of Iran (Mehrdad, Reference Mehrdad2009).

Despite these transformations, the organizational structure in this section remained unchanged in the recent three decades (Zanganeh Baygi et al., Reference Zanganeh Baygi, Seyadin, Rajabi Fard Mazrae No and Kouhsari Khameneh2016). The traditional primary health care system (PHC) in this sector have had some remaining problems including low accessibility in urban areas, low availability of expert human resources, lack of effective performance measurement, and insufficient quality of health care (Farahbakhsh et al., Reference Farahbakhsh, Sadeghi-Bazargani, Nikniaz, Tabrizi, Zakeri and Azami2012; Kiaei et al., Reference Kiaei, Moradi, Hasanpoor, Mohammadi, Taheri and Ahmadzadeh2015). The World Bank also, in a report on the Iranian health system in 2007, highlighted many achievements of the system after extension of the health care networks, and clarified some existing problems including the problems of structure, strong focus on decision making, variety of service delivery systems and the fragmentation of this system, especially in the cities (Gressani et al., Reference Gressani, Saba, Fetini, Rutkowski, Maeda and Langenbrunner2007). It was stipulated in this report that the current organizational PHC structure in Iran was significantly inefficient (Takian et al., Reference Takian, Rashidian and Kabir2010). Moghadam et al. (Reference Moghadam, Sadeghi and Parva2012) have announced many weak points for the Iranian health system in urban areas. In addition, multiple centers with different service providers have caused problems in rendering the services (Seyedin and Jamali, Reference Seyedin and Jamali2011).

Therefore, health system reforms in providing PHC services have been considered as one of the important priorities of the current government (Party of Development and Moderation) (Hafezi et al., Reference Hafezi, Asqari and Momayezi2009). In order to achieve universal health coverage and equity in health care, the public and private health complex was created in 2013 to provide health services in urban areas, especially the slum and underprivileged urban areas (Tabrizi et al., Reference Tabrizi, Farahbakhsh, Sadeghi-Bazargani, Hassanzadeh, Zakeri and Abedi2016).The aim of establishing the health complexes was to implement an effective management system and organizational structure for development in the current situation (Tabrizi et al., Reference Tabrizi, Farahbakhsh, Sadeghi-Bazargani, Hassanzadeh, Zakeri and Abedi2016).

Health complex is a new PHC reform model in Iran which was developed as a part of Health Sector Evolution Plan (Tabrizi et al., Reference Tabrizi, Farahbakhsh, Sadeghi-Bazargani, Hassanzadeh, Zakeri and Abedi2016). This system provides actively comprehensive and integrated health services within the policy framework of the Ministry of Health in a defined geographic area (Jabari et al., Reference Jabari, Tabibi, Delgoshaei, Mahmoudi and Bakhshian2007). Health complex was designed based on the capabilities of public and private sectors for an entire population in a region and based on the defined per capita and was supervised by the town’s health care and treatment network. Each health complex covers a population about 40 000–120 000 people and a health complex includes a management center, several health centers and one comprehensive health center (Tabrizi et al., Reference Tabrizi, Farahbakhsh, Sadeghi-Bazargani, Hassanzadeh, Zakeri and Abedi2016).

Private health complexes are managed by a manager with the tasks of planning, coordinating, monitoring and evaluating staff units, providing resources, responding and so on. The managers are under supervision of the director of the complex, but managers in the public health sector still do not have freedom and cannot manage like their counterparts in the private sectors (Farahbakhsh et al., Reference Farahbakhsh, Sadeghi-Bazargani, Nikniaz, Tabrizi, Zakeri and Azami2012).

Based on what mentioned above, The Iranian health planners and policy makers are trying to benefit the principles of NPM (beneficial characteristics of the private sector, market-type mechanisms, utilization of the new payment methods and decentralization), which may be assistive in increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of public health complexes and in improving the management structures of public health complexes. The Iranian health planners and policy makers want public health complexes to be managed like private health complexes and want each public health complex to be directed as independently and empowered as possible. As an effort to help health managers and policy makers in finding a better understanding on NPM in the Iranian Health System, this study aimed to identify the main elements and infrastructures of implementing NPM in East Azerbaijan Province public health complex, Iran.

Methods

Study design and sampling

This qualitative study with conventional content analysis approach was carried out between October 2016 and March 2017 in East Azerbaijan in Iran. The characteristics of the health complex in East Azerbaijan province is described in Table 1. We conducted a series of semi-structured in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of participants (n=48). Also, we conducted three focus group discussions (FGDs) with nine participants. Participants in the in-depth interviews were the managers of health centers in both public and private sectors of East Azerbaijan health complex. The main descriptive characteristics of these participants are summarized in Table 2. Also, the participants in FGDs consisted academy members of health services managers, health policy makers, health economists and physicians with experience in heath complex management (Table 3). A formal letter was sent to the health complex and emails of faculty members from the school of management and medical informatics which was included the objective of our study, a description on the characteristic of NPM and its elements as well as a consent form to participate in the interviews and FGDs.

Table 1 Characteristics of health complex in East Azerbaijan province

Table 2 Profile of interviewees

Table 3 Profile of the participants in the focus group discussions

Data collection

To collect data, three FGD sessions were held with faculty members, and 48 in-depth interviews were established with the managers in public and private health complex. Data were gathered through verbatim transcripts of semi-structured recorded interviews. Before interviews, we contacted several top and middle managers of each center to identify the name and to define a set of reform initiatives, which were currently progressed. Each interview and/or FGD lasted between 60 and 90 min. The interviews were continued until data saturation. The interviews and FGDs were conducted by one researcher and one note-taker. Our research questions (RQ) included the following items:

RQ1: What are the managers’ perspectives toward NPM?

RQ2: Which elements of NPM are suitable for public health complex?

RQ3: What infrastructures are needed to implement NPM in the Iranian public health complex?

Analytical approach

The structure of this qualitative analysis was based on a prior knowledge about NPM to investigate the elements and infrastructures for better implementation of NPM. So, the research team applied a deductive content analysis process using the theoretical framework of previous studies. The texts were read again and again and then were encoded and categorized in accordance with the created themes for analysis. Conventional content analysis approach was applied, and the themes were rechecked with the participants. To ensure the reliability of our analysis, all the analyses were separately reviewed by two researchers in the study team, and in the case of disagreement, the team made the final decision on the theme.

Findings

The 48 interviews were performed from October 2016 to March 2017. The participants included the managers with 1–31 years of experience in health care fields. The interviewees included 10 women and 38 men. The majority of participants were physicians (n=32). FGDs were conducted with nine faculty members. The participants had 1–25 years of work experience. Four out of nine participants in the FGDs (56%) were Ph.D. in health services management, health policy and health economics.

Almost all of the participants had a positive attitude toward implementing NPM. They believed that if NPM were correctly implemented, the level of efficiency in public health complex may be increased. According to two of the participants:

‘Yes, the NPM has been considered as a good goal for organizations but when we can develop this reform in our public healthcare system that our organizations would have appropriate infrastructures.’

(Ph.D.)

‘Yes, managers don’t have authority in health complex and NPM tries to increase the power of manager. Therefore, in my idea, it is a good reform for this sector and it leads to efficiency and effectiveness.’

(MS)

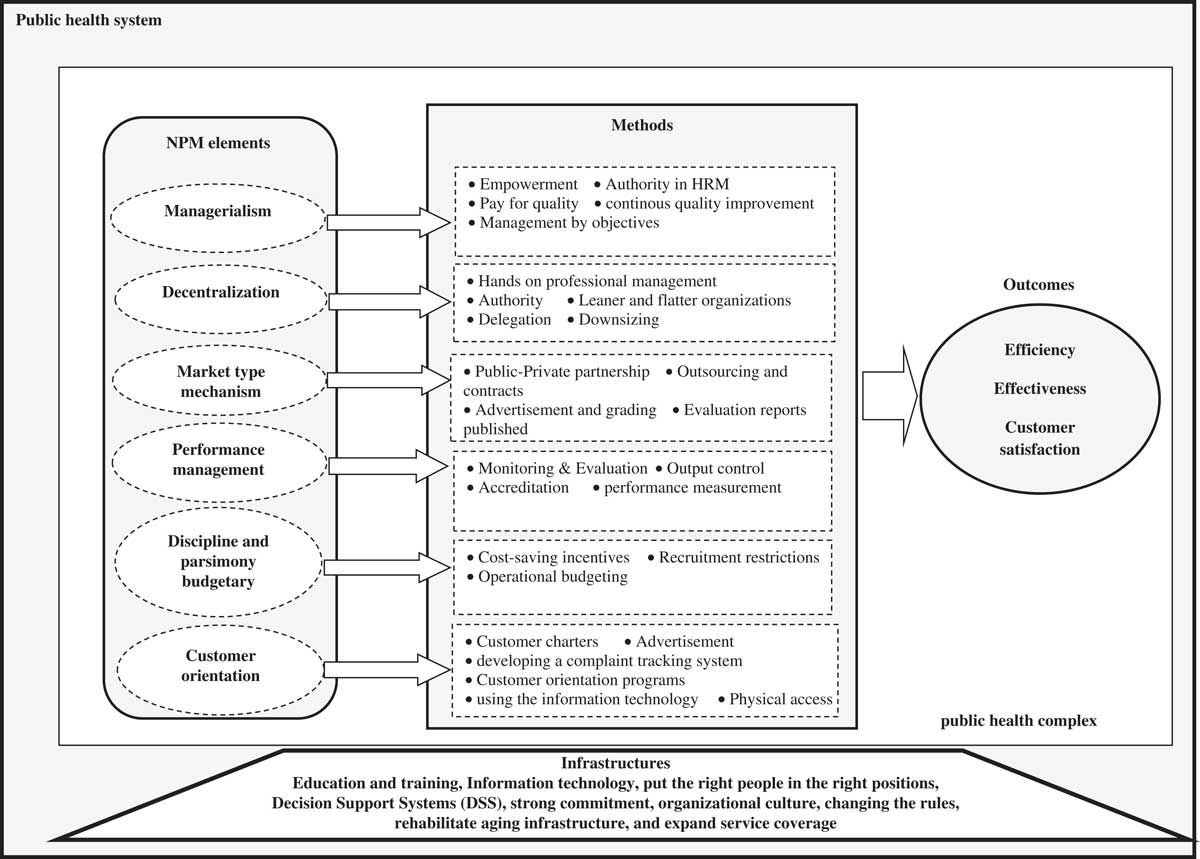

After data analysis, we designed a framework for NPM to better understand the interactions between the elements in the public health complex (Figure 1). According to the final codes extracted from the texts, the suitable elements of NPM for public health complex were categorized into six domains: managerialism, decentralization, market-type mechanism, performance measurement and new model of control, discipline and parsimony budgetary process and customer orientation.

Figure 1 Framework of new public management (NPM)

Managerialism

One of the elements of NPM was managerialism. From the perspective of managers, this element can help managers in public health organizations to manage like their counterparts in the private sector. According to three of the participants:

‘When I have authority about human resource management, like managers in the private sector, I can fairly use the rewards and punishment about my staff.’

(BA)

‘In my system, the payments aren’t based on performance. There aren’t difference between good and bad staff; therefore, good staff don’t have motivation for working while in the private sectors the payments are based on pay-for-performance.’

(MS)

‘My staff don’t have information about their job description, because it has written ambiguous.’

(MD)

The sub-themes for this element were categorized into: empowerment, authority in health resource management, pay for quality, continuous quality improvement and management by objective.

Decentralization

Authority, leaner and flatter organizations, hands-on professional management, downsizing and delegation were identified as decentralization and one of the elements of NPM which is useful for managing public health complex. Two participants stated that:

‘We should allow the managers to manage. In the public sector, unlike the private sector, managers can’t make decisions independently and the main decisions are made using the bureaucratic system.’

(MD, Ph.D.)

‘In public health complex, the managers in all functions are dependent on their senior managers, and bureaucracy is very common. In my opinion, we can’t eliminate bureaucracy in the public sector, but the system should give the delegation to managers and allow them to have a prominent role.’

(MD)

Private and public managers believed that decentralization was an important element in NPM and the implementation of the other elements are related to this element.

Market-type mechanism (MTM)

According to one participant, ‘if we want to create competitive environment, we must use the semi-market. Furthermore, our organizations can utilize the benefits of private sector using contracting and outsourcing. For example, we can contract with private sector about pharmacy management.’

(MS)

We identified four sub-themes for this element of NPM: public–private partnership, outsourcing and contracts, advertisement and grading and publishing evaluation reports. From the perspective of managers, MTM may help public sector to less monopolized the market in proportion to those that was before.

Performance management and new models of control

Another element of NPM was performance management. Monitoring and evaluation, output control, accreditation, performance measurement were the main sub-themes of performance management. Three managers stated that:

‘We need performance measurement because in our organization, monitoring is happened once a season and the payments are not based on performance and, moreover, there are not monitoring agencies in the public sector.’

(MD)

‘There are insurance deductions (30%) in public health complex, while in private sectors we don’t have any deduction, because we carefully check all of the medical documents but in public health system this is not being done. Public sector monitoring is based on input control, and it leads to inefficiency. Thus, we need a new model of control that will be based on output control.’

(MD)

‘In our system, the majority of audits are conducted at the organizational level and good staff are not motivated for this. NPM can help us using performance management with which we can recognize good staff from bad staff.’

(BA)

Discipline and parsimony budgetary process

One participant added that, ‘In the public organizations, the traditional budgeting has been used and the waste of resources is very high. Moreover, the most of staff are formal recruitments and don’t have motivation to work, because they do not afraid of getting fired. We have to try to use downsizing strategies to resolve this problem. In my opinion, NPM can help us in knowing the real amount of resources needed in our organizations. So, we have to use operational budgeting. It leads to increase efficiency, motivation and performance among staff.’

(Ph.D.)

Cost-saving incentives, recruitment restrictions and operational budgeting were the sub-themes of this element of NPM.

Customer orientation

Attention to the customer was one of the main elements of NPM. Public managers noted that customer orientation is a missing ring (Persian te) in Iranian public organizations and NPM without attention to the customer is incomplete. We identified six sub-themes for this element of NPM: customer charters, advertisement, developing a complaint tracking system, customer orientation programs, using the information technology and physical access.

‘The expectations of customers are different from one geographic area to another. So, our planning should be based on customer needs. In public health complex, and through advertisement, we can inform people about our organization’s activities.’

(MD)

‘People tend to the private sector more than the public sector, because they think that the private sector pay more attention to a customer. Therefore, we have to create a customer-oriented culture in the public organizations, and attempt to involve people in planning for their health. In addition, we can use information technology for communication with customer. For example, we can use SMS system for conveying information to the customers.’

(MD)

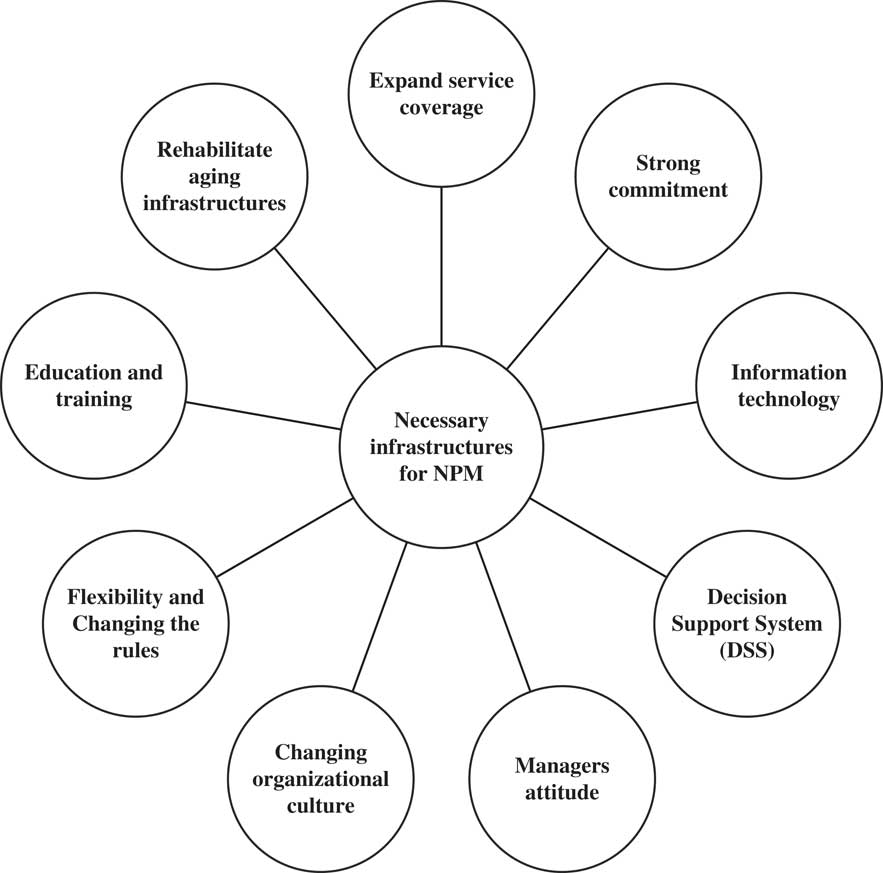

From the perspective of managers participated in the present study, nine main infrastructures are necessary to implement NPM (Figure 2). NPM may not be correctly performed in the absence of trust between managers and staffs. Furthermore, providing quality services is depended on the employees and managers attitude, skills, commitments and efforts. Moreover, the public sector managers should use information technology to assemble a mixture of technical skills with financial resources needed to implement the reforms. Flexibility and changing in rules may provide a basis for motivating, expanding, and managing the government’s human resources.

Figure 2 Infrastructures for implementing of new public management (NPM) in public health complex

Discussion

In this qualitative study, we identified six elements of NPM which are suitable for public health complex from the perspectives Iranian health managers. According to the results, the managers had an overall positive attitude toward NPM. Kalimullah et al. (Reference Kalimullah, Alam and Nour2012) identified five elements of NPM announced in the most of other similar studies: downsizing, managerialism, decentralization, debureaucratization and privatization. In another study six elements were reported for NPM: decentralization, privatization, orientation of the results from the market mechanism toward the public sector, private sector management practices, and introduction of participation. In this study, the elements of NPM were reported to be successfully implemented in public organizations (Babravicius and Dzemyda, Reference Babravicius and Dzemyda2012).

From the perspective of participants in the present study, if the elements of NPM are selected properly and in the case of infrastructures provided, the resulted reforms would improve the performance of the public health sector. Therefore, before implementing NPM, public health complex should provide the essential infrastructures. Studies have noted that developing countries cannot provide resources and managerial capacity for adopting NPM reforms (Flynn, Reference Flynn2000). In these countries, weak administrative and implementation capacity and resource constraints have been reported as the main barriers to public administration and management reforms (Batley and Larbi, Reference Batley and Larbi2004; Fernandez and Rainey, Reference Fernandez and Rainey2006). Therefore, before implementation of NPM, managers and employees need to be completely informed about such reforms. Primarily, organizational culture should be revised and information technology should be developed. Also, The organizations should be rehabilitated from the aging infrastructures and strong commitment between managers with suitable tools should be created. In many developed countries (England, Canada and Australia) and some developing countries (Egypt, Malaysia and New Zealand), the governments after providing appropriate infrastructures have been successfully performed the NPM reforms (Aucoin and Peter, Reference Aucoin and Peter1995; Hood, Reference Hood1995; Barzelay, Reference Barzelay2001; De Boer et al., Reference De Boer, Enders and Schimank2007; Constantinou-Miltiadou, Reference Constantinou-Miltiadou2015).

The most of previous studies mentioned decentralization, market-type mechanism, performance measurement, privatization, private-sector style management practices and attention to customer as the main elements of NPM (Promberger and Rauskala, Reference Promberger and Rauskala2003; Hammerschmid and Van de Walle, Reference Hammerschmid and Van de Walle2011; Engida and Bardill, Reference Engida and Bardill2013; Bačlija, Reference Bačlija2014; Constantinou-Miltiadou, Reference Constantinou-Miltiadou2015), which was similar to those found in the present study.

In NPM, aims are to apply new management methods in public organizations, with the hope to be resulted in a context with an appropriate environment for empowering the employees (Kaymakçı and Babacan, Reference Kaymakçı and Babacan2013). Public managers in our study were interested in learning new methods of management. They believed that service quality and performance in public health complex may be improved through applying managerial skills. According to their opinion, employees need to be empowered, as well.

As noted by Diefenbach (Reference Diefenbach2009) ‘the proponents of NPM believe that it will improve public services by making public sector organizations much more business-like’ (Diefenbach, Reference Diefenbach2009). Our study showed that the managers in public health complex tend to have freedom in management, and they want to participate in decision-making processes on human resource management and budgeting. They mentioned the need for delegation of authority in their systems which may lead to motivation in management. They also announced the need for more participants on the compilation of strategic plannings.

In recent years, due to technology development and more attention to employee development, organizations are demanding more creativity and responsibility from their employees (Kaymakçı and Babacan, Reference Kaymakçı and Babacan2013). Organizations and employees prefer to have employees with creativity and accountability instead of senior management, which conducted employees’ behavior and decisions (Quinn and Spreitzer, Reference Quinn and Spreitzer1997). The managers in our study mentioned the need for using technology for benchmarking and relationship with customers. They also noted that if we want to have increased level of satisfaction among customers, improved management structures and time management, we should provide our customers with information technologies like SMS system and effective automation, as well.

Decentralization was another main element of NPM (Constantinou-Miltiadou, Reference Constantinou-Miltiadou2015) and one of the central factors in changing public sector and making new public administrations (Hope, Reference Hope2001). Decentralization is a broad term, that may be defined as the transfer of authority or responsibility for decision making, planning, management or resource allocation from the central government to the field units, district administrative units, local government, regional or functional authorities, semiautonomous public authorities, parasitical organizations, private entities and nongovernmental private voluntary organizations (Dzimbiri, Reference Dzimbiri2008). Decentralization also involves the delegation of more authority over the officials working within the field, and closer to the problems (Engida and Bardill, Reference Engida and Bardill2013). Moreover, downsizing may lead to decrease in the cost of public organizations (Ferlie, Reference Ferlie1996). The results of our study showed that decentralization is somewhat implemented in the Iranian health complex but the rules are still very inflexible and bureaucracy is high. They mentioned that if we want to work with efficiency, senior managers should be trusted by public health managers and the bureaucracy should be decreased, as well.

Managers in our study noted their tendency to manage like the managers in the private sectors. They said that authority, as a factor of decentralization is an essential element of NPM needed for the well management of health systems. From their point of views, authority and effective performance are correlated together. As a result, if organizations want to maintain their managers with accountability for the output, they should give the managers some levels of control over their subordinates.

In Denmark, the delegation of financial authority and global budgets have been introduced as NPM reforms (Green‐Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2002). In Sweden, individual agencies are responsible for authority on employment and human resource management. Furthermore, collective bargaining among local-level public employers, has widely been decentralized and wage-setting systems have been reformed to make them more flexible, individualized and performance-oriented (Bach and Bordogna, Reference Bach and Bordogna2011). In the Cypriot public health sector, decentralization of managerial authority and creating flexibility to managers are main elements for NPM reforms (Constantinou-Miltiadou, Reference Constantinou-Miltiadou2015).

One of the elements of NPM mentioned by managers was performance management. The aim of this element is to report the outputs of public organizations and to apply these data to reward or penalize (Constantinou-Miltiadou, Reference Constantinou-Miltiadou2015). It is strongly and implicitly depended upon the other elements of the reform (Demediuk, Reference Demediuk2009). Performance management in Cyprus was created in response to change environmental conditions, institutional resources and individual values. This element in this country may lead to new progress in the public sector through confirmation of vision, goals, strategies, performance measures and indicators and reporting systems. Many countries like United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Norway have used performance management to improve the quality of services delivered to their citizens (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Kouzmin and Korac-Kakabadse1998; Hammerschmid and Van de Walle, Reference Hammerschmid and Van de Walle2011). Managers in our study explained that controls in the public health complex are based on inputs and not outputs which is insufficient for performance management. From their points of view, output and outcome controls as well as paying attention to quality and performance measurement are essential tools for public health complex. One of the main results of performance management was the need of public health complex to accreditation with the hope to encourage public and private health complex to compete for better and higher quality. In addition, accreditation may increase motivation between organizations for implementing effective activities.

The market-type mechanism, discipline and parsimony budgetary process and customer orientation were the other NPM elements emphasized by the health managers. Public health organizations, through market mechanisms (eg, competition with private sector, advertisement and grading), are supposedly forced to improve the quality of their services. Also, to improve the citizens’ trust and confidence, public health organization should try to make their services friendly, convenient and comprehensive.

Discipline and parsimony budgetary process was another element of NPM that draws a relationship between what organizations did and the cost of what they did (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Osborne and Ferlie2002). Many countries, after implementation of NPM elements, have found increased levels of efficiency and effectiveness in public organizations. For instance, some of the NPM elements were applied in Ghana’s health sector included downsizing, management decentralization, contracting-out, and performance contracts. In New Zealand, privatization was used to transfer the ownership of public enterprises to the private interests. Furthermore, in the public sector, it was attempted to contract arrangements for service delivery. In order to enhance accountability among managers they also used agreements, plans, budgets, financial reports and presentation of budgets, estimates, plans, and annual reports. There is no budgeting in the Iranian public health complex and it depends on the higher levels. Managers in the present study explained their need to operational and flexible budgeting. Finally, customer orientation from the perspective of the managers was very important and they need to have resources for increasing efficiency. They also noted that to increase customer satisfaction, there is a need to correct implementation of all the elements of NPM.

Strengths and limitations

We were able to interview a large sample of participants. However, due to the nature of qualitative studies, we cannot generalize our findings to the other populations. Participants in our study included both men and women from various age groups. A large number of the managers contacted by us to participate in the study announced agreement to take part in the interview sessions which indicate an excellent response rate. Also, illustrative verbatim quotes were provided for each sub-theme to demonstrate the relationship between the interpretation and the evidence for increasing trustworthiness. We did not invite the health care managers of health centers in Tehran, Shiraz and Esfahan provinces due to the recent initiation of health complex in these provinces.

Conclusion

The health care sector is of particular concern to society due to its growing costs and operational complexities. In order to solve such problems, the NPM methods have been proposed in the health care systems of a majority of Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries with the hope to avoid discrimination and injustice and to control costs. NPM is also used to provide a system with better efficiency and progress while dealing with distrust. One of the important strategies in the Iranian health system reforms is health complex. In public health complex, the managers are requested to use the characteristics of private sectors in health care delivery. Based on the opinion of participants in our study, NPM reforms may be useful for the public sector and at first, the necessary infrastructures should be provided. This framework may be a good evidence for health policy makers in PHC systems. It may be a practical guide for implementing the management reforms in PHCs. These reforms may be helpful in strengthening the public health system and the management capacity, as well. NPM also seems to be useful in interacting the public health sector with the private sector in terms of personnel and resources, performance, reward structure, and methods of doing business.

Acknowledgments

This study was based on an evaluation approved by the Deputy of Research Affairs at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. We are grateful to the East Azerbaijan Province Health Centre employees and health complex managers.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Ethical Standards

Ethical code of project for this project is: TBZMED.REC.1395.461 that was approved by the ethical committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (TUOMS). At the beginning of interview or FGD, verbal agreement was taken from the participants. The participants were told that if they want any time the voice-recording could be paused. Also, participants reassured that all information would remain confidential during the meetings.