The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic poses a significant challenge to health care workers (HCWs) all around the globe, affecting their workload and mental health (Ayanian, Reference Ayanian2020; Kisely et al., Reference Kisely, Warren, McMahon, Dalais, Henry and Siskind2020). Since workload and HCWs' well-being are related to the quality of provided care (Scheepers, Boerebach, Arah, Heineman, & Lombarts, Reference Scheepers, Boerebach, Arah, Heineman and Lombarts2015), both play a crucial role in sustaining a high work performance of the medical work force during this pandemic. Several studies investigated the mental health of HCWs during the current pandemic but reported partly contradicting findings (e.g. Lai et al., Reference Lai, Ma, Wang, Cai, Hu, Wei and Hu2020; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Socci, Pacitti, Di Lorenzo, Di Marco, Siracusano and Rossi2020; Tian et al., Reference Tian, Meng, Pan, Zhang, Cheung, Ng and Xiang2020). Moreover, all of these studies were conducted at only one time point.

With this study, we aimed to assess changes in working hours and mental health (assessed as symptoms of anxiety, depression, and burnout) in Swiss HCWs at the height of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (T1) and again after its flattening (T2). Since prior research demonstrated none or only modest changes in anxiety and depression among HCWs over the course of previous pandemics (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chou, Huang, Wang, Liu and Ho2006; Chong et al., Reference Chong, Wang, Hsieh, Lee, Chiu, Yeh and Chen2004; Su et al., Reference Su, Lien, Yang, Su, Wang, Tsai and Yin2007), we hypothesized that the difference in anxiety and depression between T1 and T2 would be smaller than the minimal clinically important difference. With regard to burnout, no hypothesis was specified.

We conducted two independent, cross-sectional online studies. Inclusion criteria for this analysis were (a) working as a nurse or physician in Switzerland, (b) being at least 18 years old and, (c) having no missing data in the variables of interest. To adjust for the differing characteristics of the two samples, participants were matched one-to-one regarding their age, gender, and profession. Under Swiss federal law, anonymous surveys do not require approval of an institutional review board. Participants were recruited with a snowball technique. Data were collected between 28 March and 4 April 2020 (T1) and between 9 May and 14 May 2020 (T2).

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were measured with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, and Löwe, Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, and Williams, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001), respectively. The minimal clinically important difference was defined as four points for the GAD-7 (Toussaint et al., Reference Toussaint, Hüsing, Gumz, Wingenfeld, Härter, Schramm and Löwe2020) and as five points for the PHQ-9 (Löwe, Unützer, Callahan, Perkins, & Kroenke, Reference Löwe, Unützer, Callahan, Perkins and Kroenke2004). Two single items derived from the Maslach Burnout Inventory (West, Dyrbye, Sloan, & Shanafelt, Reference West, Dyrbye, Sloan and Shanafelt2009) were used to assess burnout. The period of reference for all questions was the past 7 days.

Sample characteristics and median levels of symptoms were compared using χ2 and Mann–Whitney U tests and carried out in JASP version 0.12 (JASP Team, 2020). Associations between multiple variables were investigated using network analytic methods (Epskamp, Borsboom, & Fried, Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried2018). These analyses were conducted in the R statistical environment. The chosen significance level for all tests was α = 0.05.

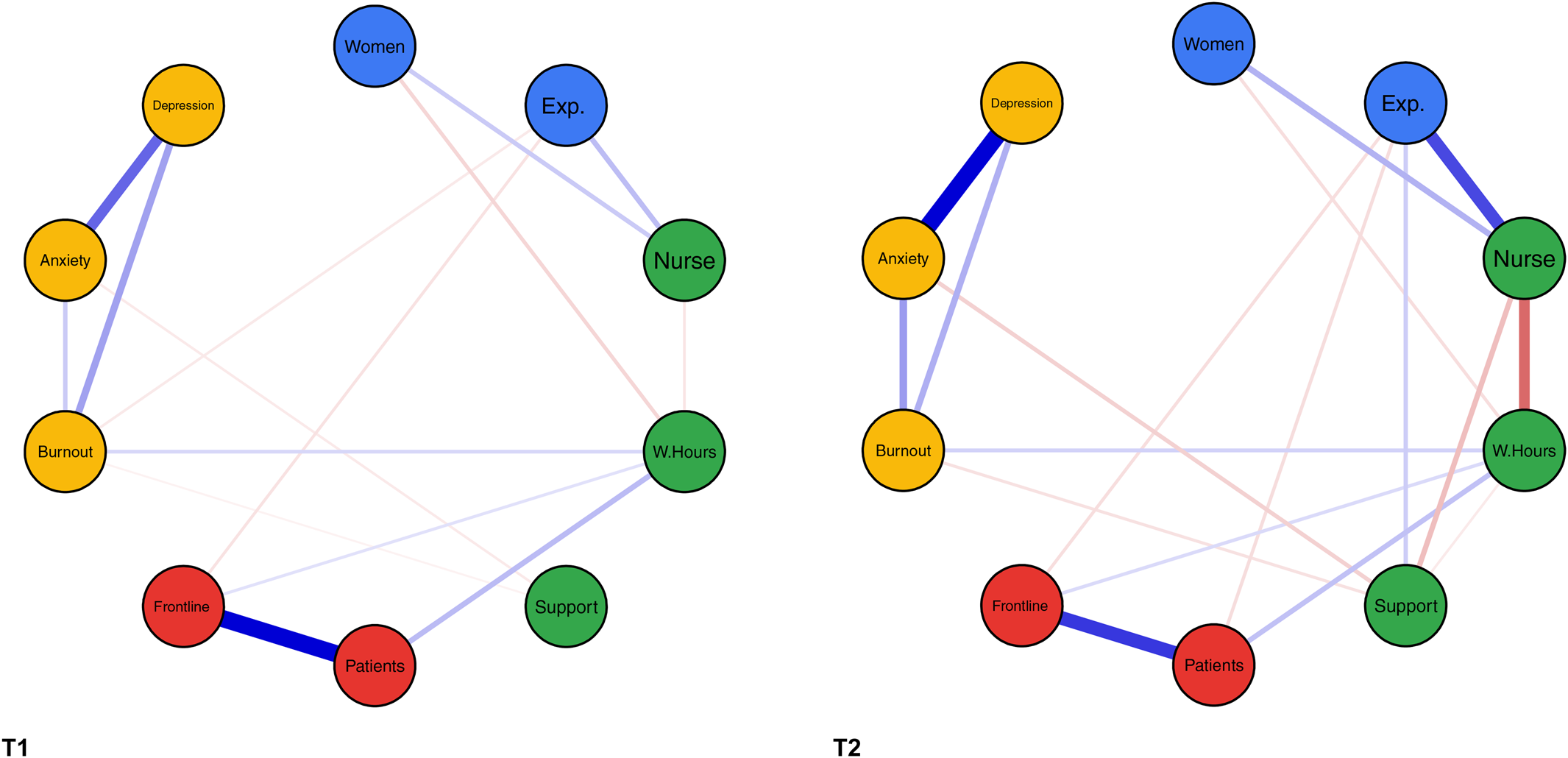

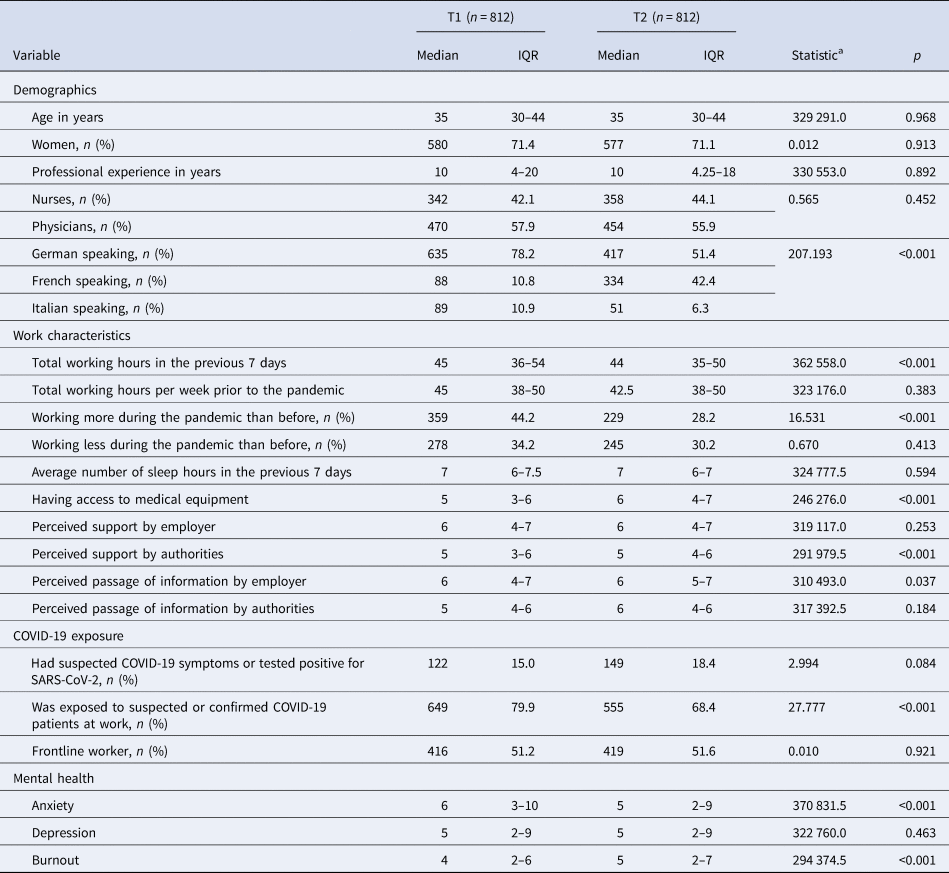

The demographics and the differences in anxiety, depression, and burnout of both samples are outlined in Table 1. The share of participants working fewer hours than prior to the pandemic did not differ between T1 and T2 (χ2 = 0.670, p = 0.413), however, less participants in the T2 sample were working longer hours than prior to the pandemic (χ2 = 16.531, p ≤ 0.001). Anxiety of participants of the first study was higher than among participants of the second study (U = 370 831.5, p ≤ 0.001, r = 0.125). Both samples had equal symptoms of depression (U = 322 760.0, p = 0.463). Participants in the second study reported more burnout than participants in the first sample (U = 294 332.5, p ≤ 0.001, r = −0.107). The results of the network analyses are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Relationships between multiple variables for two matched samples of 812 HCWs each at T1 and T2. Note. Nodes represent variables. The coloring of the nodes indicates different groups of variables (demographics, workplace-related factors, exposure to COVID-19, and mental health); edges represent associations between the nodes (continuous /green= positive, dashed/red = negative, thickness = magnitude of the relationship); women = gender (levels: men = 1, women = 2); Exp. = professional experience in years; nurse = nursing staff (variable = Profession; levels: physician = 1, nurse = 2); W.Hours = total working hours in the previous 7 days; support = perceived support by employer; patients = exposure to suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients at work (levels: No = 0, Yes = 1); ward = working in clinical unit designated to diagnosis and treatment of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (levels: No = 0, Yes = 1); burnout = overall burnout symptom score; anxiety = overall GAD-7 score; depression = overall PHQ-9 score.

Table 1. Demographics, work characteristics, and COVID-19 exposure of two age, gender, and profession matched samples of 812 HCWs each at T1 and T2

IQR = interquartile range; frontline = worked in at clinical unit designated to diagnosis and treatment of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19; burnout = burnout overall symptom score; anxiety = GAD-7 overall score; depression = PHQ-9 overall score.

a U or χ2.

Two weeks after the Swiss health care systems started to transition back to normal operations, roughly 30% were working more and 30% were working less hours compared to their usual hours in non-pandemic times. This underscores the complex impact of the pandemic and the taken measures on HCWs' working hours. The increase in anxiety is in concordance with three studies conducted during earlier pandemics, whereas the nondifference in depressive symptoms contrasts them (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chou, Huang, Wang, Liu and Ho2006; Chong et al., Reference Chong, Wang, Hsieh, Lee, Chiu, Yeh and Chen2004; Su et al., Reference Su, Lien, Yang, Su, Wang, Tsai and Yin2007). However, the differences in our study did not reach the minimal clinically relevant difference. In the case of burnout, it was of small magnitude. In the conducted network analyses burnout and anxiety were both independently related to lower perceived support by the employer in both studies, a well-described association also in non-pandemic contexts (Shanafelt & Noseworthy, Reference Shanafelt and Noseworthy2017). The nontargeted recruitment, the non-representativeness of our sample, the adaption of the questionnaires to cover the last 7 days, and the lack of data collected prior to the pandemic limit our study.

Taken together, our findings indicate that the course of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic did not substantially impact the mental health of Swiss HCWs. In addition, they emphasize the employers influence on HCWs' mental health also during this ongoing pandemic.

Financial support

Tobias R. Spiller was supported by a Forschungskredit of the University of Zurich, grant no. FK-19-048.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.