When the veil is placed about something, it hides what it contains, and makes it a secret. At the same time, however, the very presence of the veil (which is a visible object) publicly announces, as it were, that something is hidden, that here there is a secret. The veil at the same time hides and reveals, and therefore it is no exaggeration to see it as an embodiment of ambiguity.Footnote 1

Introduction

The functional purpose of curtains was to serve as partitions and screens, albeit — being made of fabric — movable and permeable ones, billowing in a draft and – depending on texture and colour — allowing light and sound to filter through. They were hung from doorways and other openings to protect interior spaces from heat, cold, drafts, dust and insects and to regulate the lighting of interior spaces. They could also be used to separate larger rooms into smaller segments, screening off specific areas that were given to specialised functions which required privacy or controlled access. Not least, especially in the case of the more ornate examples, curtains became part of the decoration of the spaces in which they were hung.Footnote 2

Their dual function as material barriers and potential points of access instigated the individual who came up to them to specific kinds of action, inviting him or her to turn away, to continue standing before them, to gaze past them or to cross them. What it was to be in each case was determined by context and social convention, by who was controlling the point of access marked by the curtain, as well as by the individual's motivations and relation to said controlling authority.Footnote 3 What stopped someone from crossing a curtain was not the actual physical object itself, but acknowledgement and respect of the authority – human or divine – that it represented, as well as fear of the unknown and the consequences that traversing the curtain without permission might entail. If these conditions did not obtain, then the curtain no longer constituted an effective barrier.Footnote 4

As barriers and screens, then, curtains served as a relatively easy-to-handle means for controlling vision, for directing physical movement and for shaping perceptions and behaviour. In addition, being found in liminal spaces both as physical boundaries and as points of access, they became imbued with a symbolic potential, which in its turn informed their use not only in ritual contexts but in art and literature as well. Existing and operating ‘in between’, they became associated with concepts of the private and the public, inclusion and exclusion, ignorance and knowledge, the visible and the invisible, light and darkness, concealment and revelation. Lifting, crossing or gazing through the curtain signalled passage from one condition to the other, a change in status, a transformation.Footnote 5

Withdrawal of an object, a person or even a specific area behind an opaque textile screen like a curtain made it automatically appear significant and distinguished. It imparted to it an aura of mystery, and hinted at a powerful and potentially dangerous presence that needed to be approached with fear and respect. The very flimsiness of the textile barrier advertised the power of that which was hidden, needing no solid walls or doors to safeguard it. One could even argue that the implication was that the curtain was there, at least in part, to warn and protect the person standing outside it from a direct and potentially dangerous encounter with what lay behind it. Still, human nature being what it is, secrecy and concealment created simultaneously the desire to attain what was hidden and heightened anticipation at the prospect of revelation. Thus, when the curtain was finally raised or pulled aside it brought release from tension and ensured engagement by provoking an emotional response compounded by feelings of wonder and privilege at being vouchsafed visual or physical access to what had originally been withheld.Footnote 6

From the foregoing, it is easy to appreciate why in different cultures curtains were consistently exploited in ceremonial performances, whether secular or religious. Indeed, following Annemarie Weyl Carr, one could claim that as media of both display and withdrawal, curtains ‘belonged to a realm of spectacle’.Footnote 7 Byzantium was no exception. The presence of curtains in the palace of the Byzantine emperors and their use in imperial ceremonial from Late Antiquity to Palaiologan times have been addressed in passing in a number of studies, above all those dealing with the ceremony of the prokypsis and its antecedents (see below).Footnote 8 In these studies, the emphasis is laid on the revelatory function of the curtains which transformed every appearance of the emperor into an epiphany. My own aim is to explore in greater depth how the performative and symbolic potential of curtains was exploited in order to communicate concepts of hierarchy, power and control and to express through spectacle the ideology and beliefs that animated the imperial establishment. The discussion will focus on the use of curtains in Byzantine imperial ritual contexts from the tenth century onwards as it can be reconstructed on the basis of written sources. The examination of the discrepancy between the presence of curtains in actual ceremonies involving the emperor's appearances in public and their virtual absence from Middle and Late Byzantine imperial portraiture will hopefully offer additional insights into the symbolism, the function and, not least, the limits of the curtain as a medium of projecting and visualising imperial power through Byzantine ritual and art.

Terminology, material attributes, modes of suspension

In contrast to the period of Late Antiquity, which has yielded many fragments of curtains,Footnote 9 hardly any Middle or Late Byzantine curtains have come down to us. Our information on the presence of curtains in the palace, on their appearance and their modes of suspension and lifting or parting derives mainly from the written sources, which use a variety of terms to describe them. Whether in addition to function, these various terms also signified differences in the appearance, length and mode of suspension of the items in question is not always possible to say.

The most common terms denoting curtains were ‘βῆλον’ (< Lat. velum = cloth, covering, awning, curtain, veil), ‘παραπέτασμα’ (< Gr. παραπετάννυμαι = to be hung before), and, less frequently, ‘κο[υ]ρτίνα’ (< Lat. cortina = curtain). As compared to the ‘βῆλον’, ‘κο(υ)ρτίνα’ probably referred to a curtain of a greater length.Footnote 10 The term ‘καταπέτασμα’ was as a rule not used for ordinary curtains outside an ecclesiastical context, being associated primarily with the veils of the biblical Tabernacle and the Jewish Temple, above all, the temple veil that was rent when Christ died on the cross (Matt. 27:51). The term ‘βηλόθυρον’ (< βῆλον [curtain] + θύρα [door]), which appears in Byzantine texts only from the eleventh century, usually designated a door curtain, including a bema-door curtain,Footnote 11 though in some texts it appears to have referred to a curtain in general.Footnote 12 ‘Βηλάρι[ο]ν’ (< Lat. velarium), on the other hand, while denoting a curtain in some contexts, in others it signalled simply a piece of fabric.Footnote 13 Finally, more generic terms like ‘βλαττίον’ (silk fabric), ‘ἔπιπλον’ (textile furnishing) and ‘πέπλος / πέπλον’ (veil) were also occasionally used to designate curtains.Footnote 14

The sources are not particularly informative regarding the materials, texture, dimensions, colour and decoration of Byzantine curtains, except for curtains employed in the imperial palace. Achmet, in his tenth-century Oneirokritikon, implies that there must have existed curtains of various densities and dimensions.Footnote 15 The material attributes of the curtains in each case would have been determined by the context of their usage. In the late twelfth century, for instance, the protosevastos Alexios Komnenos used dark-coloured purple curtains in his chambers to shut-off excess sunlight in order to sleep late.Footnote 16 Within the context of imperial ceremonial, as we shall see below, purple curtains were employed for their opacity, as well as for the symbolic connotations of their colour.Footnote 17

Beyond general references to their luxurious appearance, curtains used in the palace and in imperial ceremonies are seldom described in terms of their materials and decoration. When historical texts do go into some detail, the curtains are said to be made of silk, purple in colour or shot or embroidered with gold.Footnote 18 The use of gold thread would have added to the curtains’ density and weight and could have also affected their suppleness, contingent on how extensive it was. Not least, depending on the curtains’ location, it would also have created interesting visual effects with natural or artificial light being reflected off the golden thread.

For more information one needs to turn to the main textual source on palace curtains in the tenth century, namely the Book of Ceremonies of Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos (945-59). This text confirms the impression of the use of dark-coloured, especially purple curtains conveyed by the other sources. It also alludes to the existence of curtains adorned with a variety of techniques, including embroidery and decorative appliqués, as well as in-woven patterning.Footnote 19 While some of the palace curtains were brought out and used at various locations within the imperial palace and the Hippodrome as the need arose, others were specifically associated with certain imperial halls or particular festive occasions. During the daily reception on Sunday, for example, a curtain adorned with a motif of francolins (ταγηνάριον βῆλον) was suspended at the door of the Ioustinianos, a reception hall in the lower palace (Fig. 1).Footnote 20 The curtains of the Chrysotriklinos, the principal throne room and audience hall also in the lower palace, were reddish purple in colour (τὰ ὀξέα βῆλα τοῦ χρυσοτρικλίνου) and at least some bore figural decorations of griffins and wild asses (τὰ ὀξέα βῆλα τοῦ χρυσοτρικλίνου, οἱ γρυπόναγροι).Footnote 21 In another instance, the curtains of the Chrysotriklinos are described as woven with gold (καλλωπίζεται ὁ τῆς αὐγούστης κοιτὼν μετὰ τῶν χρυσοϋφάντων βήλων τοῦ χρυσοτρικλίνου).Footnote 22 It is possible that these constituted a different set of curtains, distinct from the red-purple ones, meant for use on special occasions. Indeed, elsewhere in the text there is explicit reference to ‘the golden curtains of Easter’ (τὰ χρυσᾶ τοῦ Πάσχα βῆλα), though it is unclear where exactly these were suspended, whether at the church of the Virgin of the Pharos, where the emperor attended the evening service on Holy Saturday, or at the Chrysotriklinos, as Albert Vogt suggests.Footnote 23 On that particular evening, the golden curtains were hung behind another set of curtains held by koubikoularioi, that is eunuch servants of the Imperial Chamber. The moment the cantor began chanting ‘Rise up, God’ all the koubikoularioi pulled the outer curtains at the same time, leaving only the golden curtains visible, the suddenness of their appearance and their golden radiance a symbol of the drama, brilliance and joy of Christ's Resurrection.

Fig. 1. The Chrysotriklinos with surrounding buildings. Redrawn, with some modifications, by Thomas Costi after M. J. Featherstone, ‘Space and ceremony in the Great Palace of Constantinople under the Macedonian emperors’, in Le corti nell'alto medioevo, Spoleto, 24–29 aprile 2014 [Settimane di studio della Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi sull'Alto Medioevo LXII] (Spoleto 2015) 587-608, fig. 3.

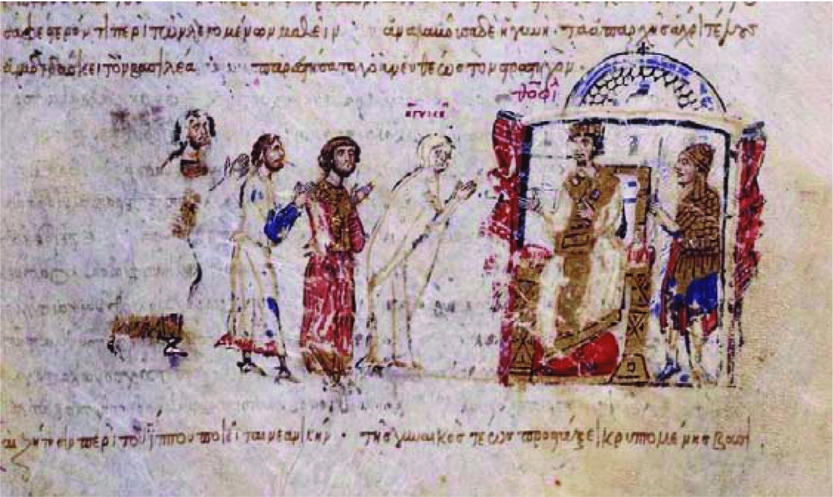

Equally limited is concrete information on the manner of suspension and lifting of Byzantine curtains. In artistic representations curtains are provided with a row of loops or metal rings through which they are attached to horizontal bars (Fig. 2).Footnote 24 Curtains could have also been suspended from rows of fixed hooks, similar to the late antique examples seen, for instance, above the lintel of the central door leading from the narthex into the nave of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.Footnote 25 Either or both methods could have been used in the palace. As to how the curtains were drawn during imperial ceremonies, the variety of phrases used in the Book of Ceremonies indicates the use of different modes at different locations and on different occasions. As Ruth Macrides astutely observed, such differences were significant and deliberate as they determined the gradual, versus the sudden, and the partial, versus the full revelation of that which was concealed behind the curtain.Footnote 26

Fig. 2. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, MS Vitr. 26-2 (Madrid Skylitzes), fol. 46r.b. Theophilos and the soldier's widow. Middle of 12th century (Photo: Biblioteca Nacional de España)

In the tenth century, on Easter Sunday curtains were suspended between two columns in the triklinos (reception hall) of the Nineteen Couches in the older section of the palace.Footnote 27 These curtains were drawn right and left (σύρουσι διχῶς τὰ βῆλα, οἷον δεξιᾷ καὶ ἀριστερᾷ), to admit various officials into the emperor's presence.Footnote 28 The so-called ‘divided curtain’ (σχιστὸν βῆλον), which was suspended at the portico of the Nineteen Couches on the occasion of the coronation of an empress, would have also had its panels drawn apart to either side in order to admit passage.Footnote 29 The use of the verb ‘ἀνοίγω’, to open, in another instance could likewise be referring to a curtain being pulled to the side.Footnote 30

A ‘drawn curtain’ (συρτὸν βῆλον) was suspended in the Chrysotriklinos, directly opposite the apse to the east, where the imperial throne stood; in one instance it is clearly stated that it was drawn aside (τοῦ δὲ συρτοῦ βήλου συρομένου) (Fig. 1).Footnote 31 Elsewhere, however, the curtains of the main western entrance to the great octagonal hall are said to be raised, rather than drawn, apparently with the help of silver beams (ἱστοπόδια), though the precise nature of the whole system is unclear.Footnote 32 Michael Featherstone, noting this apparent discrepancy has proposed that opening the western curtains involved a combination of the two modes ‘by drawing them back from the centre and raising the lower inside edges on the histopodia to the right and left’.Footnote 33 However, there is another alternative and that is that we are dealing with two different sets of curtains instead of one. The syrton velon, which is never said to be raised, separated the western vault of the Chrysotriklinos from the central space of the great hall.Footnote 34 As regards the curtain that was raised, this is in some cases specified either as the ‘western curtain’ or as the curtain of the ‘silver gates’, which adorned the western, outer entrance of the Chrysotriklinos.Footnote 35 With this in mind, I would suggest that the main western entrance to the principal reception hall of the Middle Byzantine palace was marked by two successive curtain barriers, the first, the curtain that was raised using the silver histopodia at the silver doors and the second, the syrton velon, between the western vault and the central space. A combination of curtain and door as the one envisioned for the western silver doors of the Chrysotriklinos was also to be seen at the three ivory gates of the Consistorium, the throne room of the old palace, when this hall was used for the promotion of a magistros by the emperor on an ordinary Sunday.Footnote 36 It was equally known in ecclesiastical architecture since Late Antiquity, as demonstrated by the example of Hagia Sophia mentioned above. As I have discussed elsewhere, the combination of curtain and door marks thresholds leading into the presence of authority, human and divine, with the ‘flimsier’ curtain communicating not only the presence or imminent manifestation of said authority in the space beyond but also the possibility of admittance even when the solid doors behind it were closed.Footnote 37 The existence of successive barriers at the main point of ingress to the Chrysotriklinos would have served to punctuate and pace the gradual passage from the outside to the inner most important area of the space where the emperor was enthroned, while the use of two different systems of lifting the curtain barriers would have enhanced the sensational value of being granted physical access to the imperial inner circle.

The nature of the experience of entering through a curtained threshold or seeing through it, however, depended not only on the manner of raising the curtain, but also on who did the lifting and whether he was visible or not. In the case of the curtains of the Chrysotriklinos, their opening though undertaken by specific court officials was dictated by the will of the emperor, thus conveying to the entrant the impression of being granted an honour and a privilege, while at the same time maintaining the distance, physical and hierarchical, that separated him from the ruler. On other ceremonial occasions, as in the case of the prokypsis in the Late Byzantine period, having the curtains hiding the emperor open suddenly by unseen hands would have added to the wondrousness of the imperial vision.Footnote 38

Curtains in imperial ceremonial

By the time of the compilation of the Book of Ceremonies, the use of curtains in Byzantine imperial ceremonial had a centuries-long tradition behind it. Four centuries earlier, Corippus, when describing the decorations for the inauguration of Justin II as consul in 566, explained: ‘They stretched out curtains as befitted each place. They covered them over so that they might marvel the more. That which is common is worthless: what is hidden stands out in honour. And the more a thing is hidden, the more valuable it is considered’.Footnote 39 The compiler of the Book of Ceremonies did not provide comparable commentary in his work, leaving us to extrapolate function and meaning from context, but such ideas apparently persisted throughout the period under consideration. As late as the fourteenth century, Nikephoros Gregoras, speaking of the cryptic nature of the Holy Scriptures, claims that their secret meaning is hidden behind ambivalent words and names ‘just like the chambers of the emperors and all those things that are sacred and precious to men are covered by various kinds of curtains (ὑπὸ παραπετάσμασιν), so that they do not become cheapened by being exposed to profane people and despised by being perceived easily and without trouble’.Footnote 40

Curtains feature in ceremonies taking place within the confines of the palace and when the emperor attended the liturgy at one of his capital's sanctuaries, foremost among which was the cathedral of Hagia Sophia. Even a superficial survey of the relevant references makes immediately apparent that the curtains’ main functions were to help control and ritualise access to the sacred person of the Byzantine emperor and to help safeguard his prestige and, most importantly, that of his office. The case of Michael IV (1034-41), who suffered from epilepsy, is illustrative in this respect: the moment the first signs of an oncoming seizure became apparent during a public function, the emperor's attendants would have the curtains drawn, hiding his infirmity from curious and pitying eyes.Footnote 41 Curtains were particularly associated with moments of transformation, screening the emperor when protocol demanded that he change attire during a ceremony and ensuring that he was seen in majestic grandeur when he was ready to be seen.Footnote 42 Their judicial use at these moments not only preserved imperial dignity, but transmuted practical necessity into a wondrous event, a revelation of the transformed emperor to those fortunate enough to witness it. This dramatic revelatory function of the curtain was equally pronounced on other ceremonial occasions, which did not involve a change of attire. Constantine X Doukas, for instance, would have given the impression of a providential ruler, distant yet benevolent, when he was revealed through curtains to give his inaugural speech to his court upon his accession in 1059, speaking of truth, justice and philanthropy.Footnote 43

With this in mind, one wonders whether Psellos’ comment on how Theodora disdained curtains in her interaction with her court during her sole reign (1055/6) was in fact meant to illustrate the forceful, highly visible and unmediated nature of her rule, even when compared to that of her male counterparts, rather than simply alluding, as Diether Roderich Reinsch suggests, to her abandonment of the modesty and withdrawal from the public eye that one would have expected from an imperial female.Footnote 44 Following her coronation, any empress would indeed be presented to the male members of the court through a curtain.Footnote 45 However, given that a similar public presentation through a curtain also obtained for the newly appointed prefect of the city,Footnote 46 I am hesitant about interpreting the use of curtains in relation to ceremonies involving the empress as specifically gender-related. As in the case of the prefect, and often the emperor, so in the case of the empress what the curtains helped to convey was above all a transformation and a passage from one condition to another, in this instance from the private to the public and from the sheltered world of upper-class women to the mixed, challenging world of the imperial court. This is not to claim that there was no segregation of the sexes at court; indeed, recent research has confirmed that a separate ‘court of women’ existed throughout the Middle and the Late Byzantine periods, though imperial women may not have been as confined to their ‘women's quarters’ as we tend to think.Footnote 47 However, in the light of the evidence presented here, what I am suggesting is that the ceremonial use of curtains in association with the person of the empress should not be adduced as evidence of her supposed seclusion because of her gender. Rather, I would argue, it was granted her as one more attribute of imperial status that she shared with the emperor: as we shall see below, curtains were likewise used to withdraw the emperor from the public gaze even though he was a man and to ensure the hieratic seclusion and mystery appropriate to the dignity and sanctity of the imperial office.

The focus of the ritual life of the Middle Byzantine court was the Chrysotriklinos, and reference has already been made to the curtains at its main, western entrance. The central domed space of this octagonal building was surrounded by side vaults, which, like the western vault with its syrton velon, were separated from the central area by means of curtains (Fig. 1).Footnote 48 During receptions and audiences, Byzantine officials would be arrayed behind the curtains in the vaulted spaces, awaiting to be admitted into the central area divided into groups according to rank, which were evocatively designated as ‘βῆλα’, that is ‘curtains’.Footnote 49 The red-purple curtains of the Chrystotriklinos must have had an impressive and stately appearance, serving as yet another manifestation of the resources of the Byzantine imperial establishment. Beyond that, their colour and opacity must have been deemed conducive to the creation of a mystical atmosphere, greatly desirable in the staging of imperial appearances. These dark-coloured curtains effectively prevented those on the outside from observing what lay beyond and obliged them to wait in a comparatively less well-lit space, since they must have screened-off most of the light coming in from the sixteen windows of the central dome of the throne room. At the same time, though, they must have allowed muffled sounds to filter through. By such means, the aura of mystery, accompanied by a sense of anticipation if not trepidation, must have been intensified in those awaiting admittance. When the reddish purple curtains were finally drawn, those on the outside, be they members of the court or other visitors, would enter into the brilliantly illuminated central space of the throne room to discover it dominated by the commanding figure of the enthroned emperor, who was thus revealed as a source of both power and light, detached on his throne in the apse yet very much present.Footnote 50

In addition to the Chrysotriklinos, curtains were suspended in other halls of the palace where receptions or promotions would take place. Mention has already been made of the curtains that were suspended at the triklinos of the Nineteen Couches for the reception of the court on Easter Sunday and, here we may also add, on the feast of the Pentecost. It is behind another set of curtains, suspended between two silver columns in the same hall, that, after the reception, the emperor would change into the loros-costume in order to make his stately way to Hagia Sophia.Footnote 51 Curtains regulating the ushering of dignitaries into the imperial presence according to rank were also suspended at the Triconch, a grand hall built by emperor Theophilos (829-42),Footnote 52 and at the dining hall where the emperor received various officials prior to ascending to his kathisma (imperial box) at the Hippodrome to attend the races.Footnote 53 As for the curtains that were hung outside the locked ivory doors of the Consistorium on the eve of the promotion of a magistros to be ready for use during the reception on the following day, their presence served equally as a means of announcing the imminence of the imperial advent and as a warning to the members of the court not to enter the hall since it was forbidden to gaze upon the empty throne that was placed there in anticipation of the emperor's presence the next day.Footnote 54

Curtains were also used to mark certain stations during imperial processions within the confines of the imperial palace. Rituals involving curtains marked the gradual transition of the emperor from the more ‘private’, inner sphere of his chamber and its servants to the more ‘public’, outer circle of the court, comprising the patrikioi, the strategoi, the members of the Senate and the various other tiers of dignitaries and office-holders. For instance, prior to the reception in the dining hall on the day of the races, the emperor was escorted by the members of the Imperial Chamber (ἄρχοντες τοῦ κουβουκλείου) to a nearby narrow hall or porch (στενόν), where he awaited the salutation of the patrikioi and the strategoi, who entered through a curtained doorway. It is through that same curtained doorway, one assumes, that the emperor would then proceed to the dining hall for the second, more public reception mentioned above.Footnote 55 A comparable gradual emergence of the emperor is observed during imperial processions through the upper palace to Hagia Sophia on great feast-days, such as Christmas Day and Monday after Easter. After being dressed at the Augusteus, the emperor moved to the porch (στενόν) known as the Golden Hand, where he received the proskynesis of the patrikioi and the strategoi, before proceeding first to the open courtyard of the Onopodion and then, to the following, more ‘public’ stages of the procession.Footnote 56 It is through this same curtained threshold between the Golden Hand and the Onopodion that the newly crowned empress, escorted by members of the women's court and the Imperial Chamber, would be presented to the patrikioi standing in the open courtyard, before proceeding through another curtained barrier raised by silentiarioi to a space called the Dikionion, where she received the obeisance of the patrikioi and the members of the Senate.Footnote 57 The impression that the curtained passage between the Golden Hand and the Onopodion formed a kind of interface between the more private and the more public sections of palace and court, at least during processions through the upper palace, is strengthened by the protocol for the promotion of a prefect: it is once again through this same curtained gate that the newly appointed prefect would be delivered by a praipositos, a eunuch dignitary, to the representatives of the city (πολίτευμα) gathered in the Onopodion.Footnote 58

At a practical level, the presence of the curtains in contexts such as the ones just described facilitated the orchestration of each ceremony by articulating and adorning the spaces in question, by allowing participants first, to take their allotted places unobserved and, then, by pacing their movements, and by providing cover to the emperor for prescribed changes in dress. In the case of the largely disused buildings of the upper palace, the curtains must have also provided an easy and quick way of revamping the dilapidated structures for ceremonial usage.Footnote 59 With their ornate appearance and rich tones, the curtains added to the pageantry of the proceedings, while their mere presence warned of the impending encounter with the emperor and transformed a given location into a special space appropriate to accommodate his sacred person.

The progressive emergence of the emperor from the ‘privacy’ of his chamber into the public eye on important feast days culminated with his crossing the threshold of the Chalke Gate, the old monumental entrance to the Great Palace.Footnote 60 A set of curtains – consistently called ‘κορτίναι’ probably due to their great size – were hung there, marking a permeable boundary between the palace and the city.Footnote 61 These curtains both signalled the hieratic seclusion of the sacred palace and, at the same time, announced the imminence of the imperial manifestation, which became a reality when the emperor crossed the veiled threshold to reveal himself to the public gaze.Footnote 62

From the Chalke Gate, on important feast days, the emperor would proceed to Hagia Sophia to attend the liturgy. He would arrive at the south vestibule of the narthex and there he would enter an area screened off by curtains called the ‘μητατώριον’, where a praipositos would remove the imperial crown from his head.Footnote 63 The curtains in this instance shielded the emperor at a very delicate and vulnerable moment, when he was being divested of the symbol of his worldly authority. When he emerged from behind the curtain, the emperor appeared transformed from an earthly autokrator into a servant of God. As such, he proceeded into the narthex and from there, most probably crossing a curtained threshold, he would enter, now himself a pious supplicant, into the hall of the Sovereign of All.

Within the church itself a special area at the eastern end of the south nave, also called the ‘μητατώριον’, was designated for the exclusive use of the emperor, where he could change robes and retire to attend the service when protocol did not demand his actual participation in the liturgical solemnities.Footnote 64 Whether this area was screened off by curtains, which would have been penetrated by the sounds of the liturgy, rather than by some other means, such as a marble screen, is not made explicit in the Book of Ceremonies, though in the sixth century Paul the Silentiary spoke of a wall separating the space reserved for the emperor in the church's south aisle.Footnote 65 On the other hand, Ruth Dwyer and Şebnem Yavuz in their 2012 survey of Hagia Sophia have identified rings embedded in the fabric of this part of the structure which they believe were used to hang curtains.Footnote 66 Curtains are certainly mentioned in association with comparable spaces for the use of the emperor in other Constantinopolitan churches.Footnote 67 Within the public context of the capital's sanctuaries, curtains were thus employed to maintain the mystery and isolation of imperial dignity, while at the same time proclaiming the imperial presence, at once attendant and removed.

Coming back to Hagia Sophia, according to the protocol for the major feasts, once the service was over, the emperor would depart to return to his palace through a room in the southeast corner of the Great Church. At the Holy Well, as it was called, behind yet another curtain, the emperor would reclaim his crown, this time by the hand of the patriarch in a symbolic gesture, I would suggest, meant to convey God's blessing and his continued endorsement of the emperor's divine right to rule.Footnote 68 And it is as a divinely appointed ruler that the emperor emerged crowned, once again transformed from behind a veil, to receive the acclamation of the members of the Factions waiting outside.Footnote 69

No text comparable to the Book of Ceremonies has come down to us from the period ranging from the eleventh century to the mid-fourteenth, when the treatise of pseudo-Kodinos on the offices and ceremonies of the Late Byzantine court was composed. For developments on the use of curtains in imperial ceremonial during these centuries one is by necessity limited to incidental references in historical and poetic works dating to that time. One such account is encountered in the work of George Pachymeres, speaking of the reception of Tatar ambassadors in Asia Minor by Theodore II Laskaris (1254-8). According to the Byzantine historian, the reception and everything leading up to it was managed in such a way as to instil fear in the foreign delegates and to convince them of the empire's power in order to dissuade them from thoughts of attack. Having been guided from the border through rough terrain to convince them, one supposes, that the lands of the empire could not be easily traversed by an invading force, the weary delegation was lead to the imperial presence along streets lined with heavily armed soldiers and richly arrayed courtiers, who would secretly relocate themselves along the route to give the impression of large numbers. The culmination of the reception was the revelation of the emperor from behind opulent curtains (βήλοις τε πολυτελέσι), seated on an elevated throne and holding a sword. Pachymeres underlines that the curtains parted suddenly by unseen means (ἐξαίφνης δ’ἐξ ἀδήλου τῶν παραπετασμάτων διανοιχθέντων), thus making the vision of the austere emperor appear even more awe inspiring to the eyes of the already worried ambassadors.Footnote 70

Such static, staged appearances involving the sudden revelation of the emperor from behind curtains were not addressed only to foreign visitors, but also to the emperor's own people. These appearances were often imbued with light symbolism and were meant to promote the image of the emperor as a second sun. They are already attested, in one variation or another, in the tenth century – one has in mind especially the reception of the emperor by the Factions at the Mystic Fountain of the Triconch on the eve of the races and his appearance in the imperial box at the Hippodrome – but it seems that as time passed the light symbolism became even more pronounced.Footnote 71 In a poem by the twelfth-century poet Manganeios Prodromos, for instance, the emperor Manuel I Komnenos (1143-80) is likened to the sun who gladdens the faces of his subjects by entering their hearts with his rays, ‘which send out bright glows on the surface of the curtains’.Footnote 72 The reference is probably to a ceremony that involved the use of lights and curtains, the latter perhaps shot with gold thread to better reflect the light. As Michael Jeffreys has suggested, the playful lights on the curtains are emblematic of the joy and warmth that the emperor inspires in his subjects.Footnote 73 Within such ritual contexts the curtain, apart from the medium of wondrous revelation, became the cloud that for a moment occluded the sun-like emperor, but was parted by his powerful rays so that his beneficial light could illuminate his subjects.Footnote 74

In the Late Byzantine period there was one special ceremony in which curtains and lights were used concurrently for the purpose of projecting in a quasi-theatrical manner the image of the emperor as another sun. This is the ceremony of the prokypsis, which involved the appearance of the emperor, sometimes accompanied by members of his family, on a specially constructed raised platform, which took place on Christmas Eve and Epiphany. References to the ceremony imply that it was enacted in the late afternoon and that the imperial platform was illuminated by artificial means. The emperor would ascend the stage-like dais behind closed curtains, which are said to be golden. Once everyone was in position, the signal would be given and the curtains would suddenly be drawn apart – opened, not raised – to reveal the emperor to his subjects gathered below the platform, transformed this time from a man into God's radiant, sun-like chosen representative on Earth. The ruler would be visible from the knees upwards, enhancing the impression that he was rising like the sun.Footnote 75

Many years ago Ernst Kantorowicz had suggested that the use of the curtains in the prokypsis should be ascribed to the influence of church ceremonial, where curtains at the chancel screen doors were being used, at least in some of the monastic churches of the imperial capital, already by the late eleventh century.Footnote 76 Indeed, according to the Protheoria, a liturgical commentary of the last quarter of the eleventh century, the sanctuary curtain closed after the Great Entrance to evoke the night on which Christ was betrayed and opened again at the end of the anaphora signalling the dawn when He was lead to Pontius Pilate.Footnote 77 Though the light symbolism and the revelatory function of the bema door curtains is indeed paralleled by the role of the curtains in the prokypsis, the long-established tradition of the use of curtains in imperial ceremonial that we have been tracing here suggests that if there was any connection between the two, it was imperial ritual that probably influenced ecclesiastical practice rather than the other way round.Footnote 78

On the other hand, Henry Maguire's bold suggestion that the prokypsis ceremony was inspired by imperial portraiture, itself informed by portrayals of Christ deprived of all material trappings and infused with golden light, leaves unexplained the time discrepancy between the appearance of such imperial portrayals, which are attested already in the ninth century, and the creation of the prokypsis in the twelfth or the thirteenth century.Footnote 79 Nor does it take into account the long tradition of comparable ceremonies – of which the prokypsis appears to be the culmination – involving the revelation of the emperor to his court and people from a high platform and imbued with light symbolism.Footnote 80 Equally, the proposition put forward by Warren Woodfin that the appearance of the emperor on the prokypsis from the knees upward was meant to evoke images of Christ in bust overlooks the fact that the emperor would be seen appearing like that as early as the fourth century at his kathisma, as shown in the reliefs of the base of the Obelisk of Theodosius at the Hippodrome.Footnote 81 This is not to say that the prokypsis did not promote the concept of the earthly hierarchy as a mirror of the heavenly one, nor that familiarity with religious and imperial art did not facilitate and nuance the spectators’ understanding of the message propounded by the tableau vivant of the ceremony. What leaves me sceptical is the idea that those orchestrating it would look for inspiration in art when they had the imperial ceremonial lore of centuries to draw upon. Still, even if the question of the origin of the ceremony remains open, one fact is undeniable: in the prokypsis, the transformative and revelatory function of curtains as the medium of imperial epiphany in Byzantine ceremonial truly came into its own.

Curtains in imperial portraiture

Despite the ubiquitous presence of curtains in imperial ceremonies, they hardly ever appear in imperial portraiture from the ninth century onward. This omission constitutes a departure from late antique practices, though even then the motif does not appear to have been widespread. In these early representations, a pair of curtains was depicted drawn back to either side to reveal a standing or enthroned central figure, who could be either male or female. Here the curtain has been ascribed a general honorific and revelatory meaning, appropriate to the portrayal of imperial personages in majesty regardless of gender.Footnote 82 The introduction of curtains specifically into certain early portraits of empresses has also been interpreted as a means of negotiating the empress's special status in Byzantine hierarchy and the tension between her official role, which brought her into the public gaze, and the social norms appropriate to her gender that demanded she be secluded.Footnote 83 In the light of the discussion above regarding the use of curtains in ceremonies involving the empress in the Middle Byzantine period, alternative interpretations of these early works appear possible, but exploring them goes beyond the scope of the present paper. The fact remains that in Middle and Late Byzantine imperial portraiture, whether of the emperor or the empress, curtains virtually disappear, a disappearance that becomes even more puzzling when compared with Carolingian and Ottonian royal and imperial portraiture, where curtains continue to be represented, probably in imitation of late antique models and despite the fact that curtains hardly featured in the rituals of these western medieval courts.Footnote 84 The juxtaposition of the ivory panel of Romanos II and Eudokia being crowned by Christ (945-9) with that of the emperor Otto II and Theophano also crowned by Christ, this time within a curtained niche (982-3) illustrates graphically the divergence between medieval Byzantine and western practices.Footnote 85

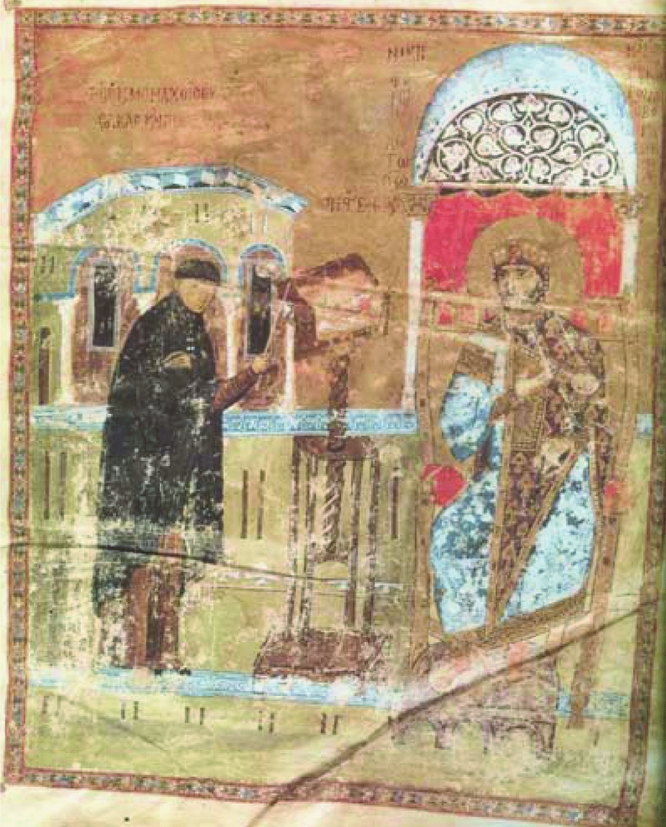

The only instance of a curtain introduced into an imperial portrayal I know of – which is more akin to a narrative scene rather than an iconic image – is the portrait of Nikephoros III Botaneiates receiving religious instruction by the monk Sabbas in Coislin 79, fol. 1(2bis)r (1071-81) (Fig. 3). A bright red curtain is suspended from a baldachin behind the enthroned emperor, framing his haloed head and making him stand out as the most important figure amongst his rather crowded surroundings. This mode of representation is more reminiscent of certain late antique representations of the enthroned Christ and the Virgin and Child, rather than the known late antique portrayals of the enthroned emperor or empress featuring curtains mentioned above.Footnote 86 Compared to late antique imperial images, this eleventh-century portrait bespeaks imperial majesty on display rather than being revealed. It is interesting to contemplate whether in this scene of religious instruction, the curtain behind the emperor had the added function of alluding to his being ‘in the know’, i.e. to his knowledge and understanding of secret teachings that for most remain hidden behind the veil of incomprehension. It could certainly help explain why the curtain was introduced here and not in other narrative or quasi-narrative representations of imperial majesty.Footnote 87

Fig. 3. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Coislin 79 (Homilies of St. John Chrysostom), fol. 1(2bis)r. Nikephoros III Botaneiates receiving religious instruction by the monk Sabbas. 1071–81. (Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France)

To my knowledge, the only extant medieval Byzantine portrayal of a historical figure of secular authority framed by open curtains is not an imperial one. The reference is to the portrait of the megas doux Alexios Apokaukos in a manuscript containing the works of Hippocrates (Par. gr. 2144, fol. 11r, dated 1341–5) (Fig. 4a-b). Whether the manuscript was commissioned by Apokaukos himself or whether it was presented as a gift to him is unknown. The megas doux is revealed to the viewer by a pair of open red curtains striking an elegant pose on an impressive wooden throne while gesturing towards a lectern on which a codex lies. The book is held open by an unidentified young male figure, who stands half-hidden behind Apokaukos’ throne. The famous doctor himself is portrayed on the opposite folio, enthroned beneath a different type of hanging made of supple blue fabric, which is suspended horizontally above his head by what look like ropes at the two corners. This type of horizontal drapery, which resembles a raised theatre curtain, is called aulaeum by Eberlein.Footnote 88 The difference in the type and the colour of the drapes associated with the two figures was possibly meant to highlight the difference in their status, one being an ancient sage, the other a living Byzantine notable.Footnote 89

Fig. 4a-b. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Par. gr. 2144 (Works of Hippocrates), fols. 10v-11r. Hippocrates (left) and the megas doux Alexios Apokaukos (right). 1341–45. (Photos: Bibliothèque nationale de France)

While the drapery above Hippocrates finds parallels in certain contemporary evangelists’ portraits, themselves reproducing earlier eleventh-century models when this type of horizontal hanging appears to have enjoyed a short period of popularity,Footnote 90 the curtain motif in Apokaukos’ portrait finds no parallels in Middle or Late Byzantine portraiture. It is equally exceptional in Byzantine religious iconography, where it was introduced into the portrayal of saintly figures in certain manuscripts associated with the so-called Macedonian Renaissance, but was apparently abandoned soon after.Footnote 91 On the other hand, the juxtaposition of an enthroned figure of secular authority revealed by a pair of curtains and the figure of an author, saintly or otherwise, beneath the aulaeum occurs in a group of Carolingian manuscripts.Footnote 92 Whether the Byzantine example and the much earlier western ones hark back to a common late antique prototype I cannot say. What one could claim is that the scheme adopted in the Byzantine manuscript is an archaizing one, probably intentionally so as a means for displaying Apokaukos’ erudition and culture despite his humble origins, the latter often criticised by his opponents. In the verses that are addressed to Apokaukos as if from the mouth of Hippocrates, he is described as a brilliantly accomplished and successful man and it is thus, I would argue, that he is revealed through the curtains, arrayed in his impressive court dress and his official headdress, adorned with the figure of an enthroned emperor.

The absence of curtains from Middle and Late Byzantine imperial portraiture, despite the existence of late antique models and the significant role they played in imperial ceremonial performances is puzzling. It becomes even more so when one realises that a comparable absence may be observed in religious iconography as well: numerous late antique precedents notwithstanding,Footnote 93 curtains as a framing device also disappear from iconic representations of Christ and the saints in post-Iconoclastic Byzantine art, especially after the tenth century. The only iconic religious pictorial contexts in which curtains or an auleum are sometimes introduced are seated portraits of evangelists at work. Here, the curtains allude to the revelation of divine truth through the Gospels made possible in the first place by Christ's assumption of flesh, which was equated with the temple's katapetasma (Hebrews 10: 20).Footnote 94 Interestingly, though iconic sacred portraits lack curtains, depictions of actual icons in art are often shown with (raised) icon veils, echoing current devotional practices.Footnote 95 The use of such screening veils for icons, especially from the eleventh century onwards, invites the question whether real veils were likewise used to screen imperial portraits and whether this may be the reason that no images of curtains were depicted framing the imperial figures in portraiture.Footnote 96 However, I am not aware of any evidence, written or other, for the suspension of screening veils or curtains in front of imperial portraits in Byzantium.

One probable explanation would be that curtains were omitted from imperial portraiture and iconic representations of Christ and the saints alike as part of the trappings of the material world that had no place in the heavenly setting in which these figures were represented and which Christ and the Christ-like emperor were thought to share. In this respect, it is noteworthy that it is not just curtains that are omitted, but all elements of an architectural background that, had they been included, would have detracted from the portraits’ spiritual and transcendental aspect with their materiality and spatial specificity.Footnote 97 Nevertheless, given that other ceremonial paraphernalia like thrones and footstools were included in Middle and Late Byzantine portrayals of both Christ and the emperor, I would like to propose an alternative though not necessarily contradicting hypothesis regarding the omission of curtains.

To my mind the reason for the absence specifically of curtains in Middle and Late Byzantine imperial portraiture can also be sought in the divergence between art and ritual when it comes to conveying a message and in the nature of that message. An imperial ceremony was a transient process, and its message was performed within a specific spatiotemporal frame using spectacular and dramatic means meant to ensure the engagement of its intended audience. Within this context the curtains functioned as the medium of revelation, alluding to the existence of a secret that was briefly exposed when they were drawn, to be removed again from view and direct knowledge when they were closed. Thus, through carefully managed concealment and revelation, they helped to maintain the mystery of the imperial office embodied in the reigning emperor and to ensure that both continued to be honoured, respected and feared by remaining largely distant and not easily approachable.

The purpose of the imperial portrait, however, was different. Yes, its aim, like ceremonial, was to convey a statement on the nature of the imperial office and on the emperor's relationship to God. In the portrait, however, there were no secrets or shrouded mystery: through the image, the truth about imperial power – a truth that was presented as timeless, universal and unchanging – was immediately and directly made accessible to all who gazed upon the portrait.

Behind this function of the image as the medium of revelation of truth one may detect the impact of Byzantine icon theory, as crystallized after Iconoclasm. This theory was predicated on God being revealed in the world by Christ's Incarnation and Passion: through His voluntary sacrifice, the temple veil – Christ's own flesh (cf. Hebrews 10:20) – was torn to open the way to God for humankind. Apart from making it possible for all to reach God, being made visible in the world, the incarnate Christ was also able to be portrayed, and such beliefs lead to the creation of images that were thought to provide direct and otherwise unmediated access to the sacred persons represented.Footnote 98 With this in mind, I would suggest that within the context of post-Iconoclastic imperial portraiture — as within the context of representations of Christ and the saints — it was the image itself that was the instrument of revelation. The curtains not only as revealing agents but also as ‘an embodiment of ambiguity’, hinting at secrets where the Byzantine image / icon by its very conceptualisation admitted none, were both redundant and counterproductive in these artistic contexts, and it is for this that I believe they were omitted.

Concluding remarks

The fascination of curtains lies not only in their inherent value as artefacts, but also in their power to endow other artefacts, spaces and persons with value and, not least, mystique.Footnote 99 Curtains in Byzantine imperial ceremonial were much more than simple props that added to the opulence of the spectacle and advertised the resources of the court. Being carefully manipulated, they helped cultivate, safeguard and project the importance of the Byzantine emperor and communicate statements regarding the nature of his authority and rule. By keeping him physically separate from his court and subjects, they maintained the mystery and sacredness of his office. In this spatial segregation the special status of the emperor as the pinnacle of the Byzantine court hierarchy and as God's chosen representative on Earth was performed in the most immediate and dramatic way for maximum effect. At the same time, the curtains, simply by being there, announced the presence of the emperor and his impending manifestation, while their permeability proclaimed to all that, though aloof and operating at a different level, he was nonetheless approachable, as befitted a benevolent and magnanimous Christian ruler.

The curtains’ transformative power turned Byzantine ceremonial performances into wondrous events where all the participants on either side of the curtain barrier became fully engaged by experiencing a change: for those inside the curtain, this change involved a transition from being hidden to being revealed; for those outside it, from unknowing and unseeing to knowing and bearing witness. Indeed, the curtains transformed the spectators from passive observers into involved, and by extension, responsive partakers in the ritual unfolding before their eyes. Given that without the intended audience's response, a ceremony's message would be lost, it is little wonder that curtains were ascribed such a central role in Byzantine imperial ceremonial.