Obesity is a complex, multifaceted public health problem in which the food environment plays a key role ( Reference Vandenbroeck, Goossens and Clemens 1 ). Out-of-home (OH) eating is one aspect of the food environment that is becoming increasingly important in promoting overeating and excess energy intakes. The increasing trend in OH eating has been well documented in the USA( Reference Kant and Graubard 2 , Reference Adair and Popkin 3 ), but a lack of consistent data and definition of OH eating has hindered the identification of any clear trends for the UK and Republic of Ireland (ROI). In the UK, OH eating accounted for 11 % of total energy intakes in 2011( 4 ) but the definition of OH eating was not clear, with the exception of including school and work meals. In ROI, OH eating contributed 24 % to total energy intakes when restaurants, takeaways, shops and delicatessens were included( 5 ).

In adults, OH eating has been associated with larger portion sizes( Reference Kant and Graubard 2 , Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulou 6 , Reference O’Dwyer, McCarthy and Burke 7 ) and higher energy intakes( Reference Kant and Graubard 2 , Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulou 6 – Reference Mancino, Todd and Guthrie 9 ) but lower micronutrient( Reference Lachat, Nago and Verstraeten 8 ) and fruit and vegetable intakes( Reference Orfanos, Naska and Trichopoulou 6 , Reference Mancino, Todd and Guthrie 9 , Reference Larson, Neumark-Sztainer and Laska 10 ). Similar findings have been found for children, suggesting that children who eat OH frequently have higher intakes of total energy, total fat, total carbohydrate, added sugars and sugar-sweetened beverages with lower intakes of fibre, milk, fruit and vegetables( Reference Ayala, Rogers and Arredondo 11 , Reference Bowman, Gortmaker and Ebbeling 12 ). Fast-food establishments and restaurants were found to contribute more to total energy intakes (14·8 %) than meals and snacks consumed in schools or day-care centres (8·7 %) by US 2–18-year-olds( Reference Adair and Popkin 3 ). Therefore, not surprisingly, high consumption of OH food has been associated with weight gain in children and adolescents (4–19 years)( Reference Rosenheck 13 , Reference Birch, Fisher and Davison 15 ).

The overall family food environment plays a pivotal role in developing children’s eating behaviours and parental eating habits have been correlated with children’s eating behaviours( Reference Birch, Fisher and Davison 15 – Reference Johannsen, Johannsen and Specker 19 ). Furthermore, regular family meals have been associated with lower levels of overweight and obesity( Reference Patrick and Nicklas 17 , Reference Gillman, Rifas-Shiman and Frazier 20 – Reference Taveras, Rifas-Shiman and Berkey 22 ), but parents in the USA admitted that eating together as a family occurred more frequently OH than in the home( Reference Fulkerson, Story and Neumark-Sztainer 23 ). If similar trends become the norm in the UK and ROI then there is clear scope for supporting families who regularly eat OH to select more healthy food items, particularly as childhood eating habits and obesity can track into adulthood( Reference Provencher, Perusse and Bouchard 18 , Reference Singh, Mulder and Twisk 24 ). Given that 77 % of Irish children (aged 5–12 years) ate OH at least once per week in 2004( 25 ) and that food establishments offer meals specifically for children, the OH eating context for children should be a key focus for public health. There has been an increased understanding of what influences children’s food choice decisions at home including taste, hunger, advertising, availability of food, body image and peers (e.g. references Reference Holsten, Deatrick and Kumanyika26–Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry29), but little is known about the role of these factors when children eat OH. A better understanding of family OH eating will help to plan future public health strategies in this complex eating context. The WHO has advocated the inclusion of all stakeholders in public health policies and interventions( 30 – 32 ) and there appears to be a willingness among OH caterers to engage in healthier eating initiatives, provided consumers find these acceptable( Reference Obbagy, Condrasky and Roe 33 , Reference Lachat, Naska and Trichopoulou 34 ). However, little is known about the motivation for families to make healthier OH food choices and clarification of this issue would help to ensure that public health interventions are likely to be effective.

Therefore the aim of the present paper was twofold: (i) to explore the factors influencing family OH eating events; and (ii) to identify possible opportunities for food businesses to support families in making healthier OH choices. For this purpose, family OH eating has been defined as any food or beverage that has been cooked outside the family home for a family to eat together, including takeaways but not including ready meals purchased in a supermarket( Reference McGuffin, Wallace and McCrorie 35 ).

Methods

Qualitative research methods were selected for an in-depth exploration of the factors influencing family OH eating. Both parents and children participated in the research to gain a more complete perspective of family dynamics when eating OH together. To maximise the range of family perspectives obtained in the research, parents and children were not related. Focus group discussions were selected for parents as the most appropriate method of encouraging parents to interact and obtain a better understanding of their perspective of family OH eating. Friendship pair discussions involve two children who are friends and were selected as the most appropriate method of encouraging communication with this age group( Reference MacDonald, Miell and Morgan 36 ). In addition, the moderator is able to redirect questions between the children and encourage them to discuss questions between themselves( Reference Jones, Mannino and Green 37 ) while avoiding the potential for biased responses that might occur as a result of either peer pressure in larger groups or in one-to-one interview situations. The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human participants were approved by the University of Ulster Research Ethics Committee (REC/11/0057). Written informed consent was obtained from parents and children.

Recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to recruit parents (of children aged 5–12 years) and children (aged 5–12 years) from the island of Ireland during June–August 2011. Inclusion of children and parents of children aged 5–12 years was selected so as to incorporate those most likely to be targeted by children’s menus when eating OH. A market research company was engaged to recruit a sample of parents and children by face-to-face methods. Both parents for the focus groups and parents of children for the friendship pairs completed a short characteristics questionnaire to ensure participants represented equal numbers of gender, age (parents <35 years, ≥35 years; children aged 5–6 years, 7–8 years, 9–10 years, 11–12 years), socio-economic status (high and low) and demographic backgrounds (location on the island of Ireland). If a respondent met the desired criteria for that session, he/she was formally invited to take part. Parent and child characteristics of those who participated are displayed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 Characteristics of focus group participants: purposive sample of parents (of children aged 5–12 years) from the island of Ireland, June–August 2011 (n 186)

* Market Research Society grading of occupations: high, occupations categorised as A, B and C1; low, occupations categorised as C2, D and E( 48 ).

Table 2 Characteristics of friendship pair discussion participants: purposive sample of children (aged 5–12 years) from the island of Ireland, June–August 2011 (n 96)

* Market Research Society grading of occupations: high, occupations categorised as A, B and C1; low, occupations categorised as C2, D and E( 48 ).

Focus group (parents) protocol

Twenty-four (n 8 in Northern Ireland; n 16 in ROI) mixed-gender (with the exception of one all-female) focus group discussions were conducted (six to eight participants in each group), each lasting approximately 90 min. The discussion topics are listed in Table 3 and were based on previous literature on food choice in the home and discussions by the research team; however, the schedule was also flexible to allow parents to raise issues of importance to them.

Table 3 Semi-structured discussion areas for focus groups and friendship pair discussions

One of three experienced moderators facilitated the discussions (A.L., N.B., D.M.), which were held in informal settings convenient to participants. A note taker was also present but did not participate (L.E.M., R.K.P.). At the outset, the moderator explained that the discussions were concerned with family experiences of eating OH but no explicit reference was made to nutrition or health. Parents were asked to introduce themselves and as an ice-breaker reported how many children they had and where they liked to eat OH as a family. The moderator encouraged participation from all parents and prompted elaboration on issues related to the discussion guide or unanticipated but relevant topics. An honorarium was given to parents for time and travel costs (£30).

Friendship pair (children) protocol

Forty-eight (n 16 in Northern Ireland; n 32 in ROI) friendship pair discussions were conducted with children of the same age and gender. Each lasted 15–30 min, depending on the motivation and ability of the child to engage in the discussion (i.e. discussions times were curtailed if the children were distracted and not willing to participate fully). A semi-structured discussion guide (Table 3) was developed to complement the discussion guide developed for the focus group discussions, but it was also flexible to tailor the discussions to the children’s cognitive ability (i.e. younger children were unable to recall information, such as establishment names) and interest.

One of three experienced moderators facilitated the discussions with children (A.L., N.B., D.M.) and a note taker was also present during the discussions (L.E.M., R.K.P.). Parents were invited to sit in on the discussions if they wished but did not participate in the discussions. As an ice-breaker children were asked where their favourite places to eat OH were and what foods they liked to order OH. The moderator encouraged both children to participate and discuss issues between themselves. When all of the topics in the discussion guide were addressed children completed a quiz to facilitate further discussion. Children were presented with seven word pairs of food typically available OH, one of which was considered to be ‘healthy’ and the other ‘less healthy’ (Table 3). They were initially asked to select which food they preferred and then which one they perceived as being ‘healthier’. At the end of each friendship pair discussion an honorarium in the form of a book token was given to each participating child (£10 for each child, £10 for parent to cover travel costs).

Analysis

Focus group discussions were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim, with researchers present as note takers checking transcripts for accuracy with original recordings and field notes (L.E.M., R.K.P.). Friendship pair discussions were audio-recorded and field notes were taken throughout. Transcripts were analysed using a thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke( Reference Braun and Clarke 38 ), independently by two researchers (L.E.M., R.K.P.). NVivo 9 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) was used for more effective data management.

Data familiarisation was achieved by repeated reading of the transcripts and listening to the audio-recordings. The focus group and friendship pair transcripts were analysed separately by systematically coding the data under the main discussion topics (to allow main themes for each discussion topic to emerge). A standard coding format was agreed by the two researchers by coding five randomly selected transcripts. Related codes were then independently collated into potential themes and repeatedly reviewed and refined to ensure they reflected the coded extracts and data set as a whole. Theoretical saturation was reached at approximately eighteen transcripts for the focus groups and twenty-four for the friendship pairs. The two researchers discussed the findings and good agreement was achieved on themes, with full agreement being reached after minor clarifications (inter-rater reliability of 1·00). The agreed themes were checked to ensure there were clear distinctions and the final themes were named and defined. Appropriate extracts from the focus groups and friendship pairs were selected and agreed to support the final themes.

Results

The main theme that emerged from both parents’ and children’s discussions regarding reasons for eating OH was ‘as a treat’ and for parents the main theme for selecting what establishment to eat in was ‘family friendly’ aspects. In terms of children’s OH food choices, ‘taste and food preference’ were paramount, while parents were more concerned with permitting children to have a treat. The themes that emerged from parents’ and children’s discussions are presented below under the main discussion topics.

Reasons for eating out-of-home

Parents reported they predominantly make the final decision for the family to eat OH and the reasons for doing so are listed in Table 4. The most important motivating factor for parents to decide to eat OH was to ‘treat’ their family. Eating OH was an opportunity for families to eat together and allowed parents to spend quality time with their children without being distracted by cooking or household chores. It was also perceived by parents as a convenient alternative to eating at home where the family has a break from the everyday eating pattern. The comments from the children complemented those of the adults, namely that they eat OH ‘as a treat’ and ‘to give mummy/daddy a break in the kitchen’.

Table 4 Factors that influence family out-of-home (OH) eating among purposive sample of parents (of children aged 5–12 years) from the island of Ireland, June–August 2011 (n 186)

Another reason cited for eating OH was the wide range of special offers available and the ready accessibility of a range of eating establishments near family homes. Parents also perceived that the cost of OH eating was comparable to eating at home, if not cheaper in some cases.

Choice of out-of-home eating establishments

After parents initiated the decision for the family to eat OH, they often permitted their children to choose the establishment (Table 4) as a method of ensuring their child was engaged and more likely to finish his/her meal. Parents believed their children selected an establishment based on marketing techniques, such as advertising, free toys and/or the food available.

From the parent’s perspective, ‘family friendly’ aspects of the establishment were of key importance when choosing a location as this would be more likely to ensure the entire family enjoyed the experience in an environment where they all felt comfortable. Parents were attracted to establishments that provided a form of entertainment/diversion for children, such as colouring pencils, a clown or bouncy castle.

Cost was a major factor influencing parental choice of eating establishment. Knowing the cost of the family meal before entering the establishment (e.g. set menu price, chain establishments) was appreciated by parents as they could budget for the occasion and hoped to avoid extra costs, such as drinks and desserts.

The time available for eating the meal tended to dictate which establishment was selected by the family. When eating OH for a social occasion, a sit-in restaurant with a slower service time was more likely to be selected. Alternatively, if time constrained, a fast-food type establishment with rapid service was likely to be the choice. In general, establishments with fast service times were preferred by families, particularly parents with younger children, as this helped avoid children becoming bored and possibly disruptive.

Family meals OH were more enjoyable in establishments that were perceived to be stress free. Therefore parents preferred to patronise establishments where there was previous experience of family enjoyment or somewhere recommended by other families. The nutritional quality of food was of lesser importance to parents when selecting an establishment; treat and enjoyment factors had greater priority for them. A better standard of food and service was sought when eating OH for a special occasion, such as a birthday; therefore a full-service restaurant was more likely to be selected by parents on these occasions.

Children’s out-of-home food choice

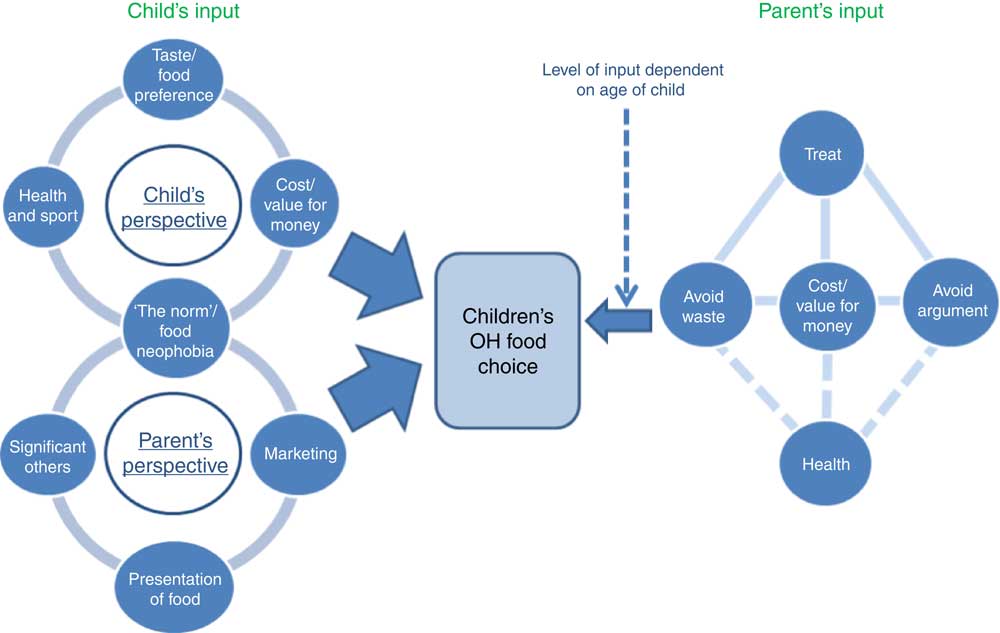

Figure 1 is a diagrammatic representation of factors that were reported to impinge upon children’s OH food choice decisions. Parents and children both contributed to a child’s final food choice decision (Table 5) and the child’s decision has been reported from the parent’s and child’s perspective. In general, children exerted most control over the final food choice decision and parental input varied depending on the age of the child, with younger children given less control. It was evident that children have their own opinions about what affects their food choice decision and these were first and foremost ‘taste/food preference’ followed by ‘cost/value for money’ and ‘health and sport’. Parents also provided insight into the factors they believed influenced their children’s food choice decision and these were ‘marketing’, ‘presentation of food’ and ‘significant others’. The only common factor reported by both parents and children as influencing a child’s decision was ‘the norm/food neophobia’, whereby children were afraid to try new foods or when foods were presented differently; therefore they preferred to select foods they were familiar with. Factors influencing parental input were ‘treat’, ‘avoid waste’, ‘avoid an argument’ and to a lesser extent ‘health’.

Fig. 1 Factors impinging on children’s out-of-home (OH) food choice decisions. Both parents and children contributed to the OH food choice decision, therefore factors influencing food choice are grouped under ‘Parent’s input’ and ‘Child’s input’. Parental input varied depending on the age of their child and in general children had most responsibility for the final decision, as indicated by the larger arrows. The child’s input was investigated from the parent’s and child’s perspective in focus groups and friendship pair discussions respectively and the only common factor reported by both parents and children was ‘the norm’/food neophobia. Factors influencing the parental input were prioritised with ‘treat’ having the strongest influence, followed by ‘avoid waste’ of food, ‘cost/value for money’ and ‘avoid argument’ with their children on a similar priority level (![]() ). These all were more important than ‘health’ and the dashed lines (

). These all were more important than ‘health’ and the dashed lines (![]() ) indicate ‘health’ was only considered if these other priorities were satisfied

) indicate ‘health’ was only considered if these other priorities were satisfied

Table 5 Factors that influence child and parental input into the child’s final out-of-home food choice decision among samples of children (aged 5–12 years; n 96) and parents (of children aged 5–12 years; n 186) from the island of Ireland, June–August 2011

Locations on the island of Ireland (North/South, rural/urban), age of parent and socio-economic status were not found to affect the factors involved in children’s OH food choice, but age of child, and in some cases gender, may have influenced the priority of themes. For example, older girls may be given more control over their own food choice decisions than boys of the same age:

‘Girls [start choosing themselves] at 4. The boy you would get away with [telling him what to order up to] 9 or 10.’ (Parent)

‘Give them less choice the younger they are. I mean they can’t read the menu.’ (Parent)

‘I might try with the younger ones, I’ll try and steer them towards something more healthy but the older [children] – I have no say.’ (Parent)

Child’s contribution to out-of-home food choice decision

Child’s perspective

From the child’s perspective, the most important factor that influenced their food choice decision was taste/food preference (Table 5). Food neophobia was another major factor found to contribute to a child’s food choice decision and was reported by both parents and children. Overall, children discussed ordering familiar foods that they like the taste of, irrespective of the type of establishment they were discussing. Chinese and foods from carveries and buffets were the only instances when children recalled a wider variety of foods such as roast meats, potatoes, vegetables, curries, spicy chicken and rice.

For older children (>11 years) who ate OH with their friends as a social event, cost and value for money impacted on their food choice. These factors were largely irrelevant when they ate OH with parents.

There were conflicting reports from children with regard to health issues for eating OH. Some older children (>8 years) discussed the importance of ‘healthy food’ in relation to sport and how this might affect their choice. However, the quiz demonstrated that the main reason for children liking a food was taste preference, with health implications or ‘healthiness’ having minimal impact. Children categorised foods as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ and all children perceived ‘good’ foods as anything that was, or contained, fruit, vegetables, milk and water. Knowledge of health increased with child age and older children were able to explain in more detail why foods were healthier:

‘Fish fingers are healthy, they are fish.’ (Boy, age 5–6 years)

‘Salmon is better because fish is good for the brain and fish fingers aren’t [healthy] because they’re fried.’ (Girl, age 11–12 years)

‘Milk’s good because it’s healthy.’ (Girl, age 5–6 years)

‘Milk is healthier as it’s full of calcium which is good for like your bones and teeth.’ (Boy, age 11–12 years)

Parent’s perspective

Parents reported food neophobia was a problem frequently encountered with their children (particularly younger children) but in the OH environment this was particularly evident. In general, parents believed children’s menus were very limited and of lower nutritional quality compared with the adult menu, with processed meats dominating the menu at the expense of healthier items such as fruit and vegetables. However, parents of younger children and ‘fussy eaters’ appreciated the almost standard nature of children’s menus between establishments.

Parents believed marketing techniques used by OH establishments or how food was presented strongly influenced their child’s food choice decision. Younger children in particular were reported to be affected by attractive packaging or foods presented in shapes, as well as free toys and television advertisements. Children’s peers were also considered by parents to affect children’s food choices both positively and negatively, and parents themselves felt some pressure from children’s peers to ‘conform to the norm’ (Table 5).

Parents did not consider that health played any role in a child’s OH food choice decision despite their belief that children had a good awareness of nutrition from education in school.

Parent’s contribution to out-of-home food choice decision

Parents had strong feelings that OH eating should be a treat and was expected to be an enjoyable eating experience where parents can feel less guilty about relaxing normal food-related rules that they may have when eating at home (Table 5).

For parents ‘wasting food’, ‘avoiding an argument’ with their children and ‘cost/value for money’ were the other key factors that influenced what they would like their children to order OH (Table 5). After ‘treat’, these were on a similar priority level and were interrelated. For example, parents did not want children to order a menu item that was too expensive or was likely to result in plate waste (such as having a large portion size, food not liked), but compromises were made in the face of counter-argument by the child. Despite parents reporting that they would like to consider health for their children’s food choices when eating OH, health considerations were overshadowed by these priorities. Consequently, parents were less likely to encourage a healthier OH food choice if it was at odds with the child’s choice or interfered with their own priorities (Table 5). Healthier items were associated by parents as not being good value for money and likely to increase the risk of food neophobia and food wastage. However, parents also discussed strategies they might use to encourage children to make small health compromises (Table 5).

Opportunities for healthier out-of-home eating

Healthier food choices for children when eating out of home

Parents believed they had most responsibility for what children ate OH but that OH establishments also had a key role to play in supporting families by providing an appropriate selection of healthy, in addition to less healthy, options. While parents currently perceived OH eating as generally unhealthy, they did consider ‘traditional‘, ‘fresh’, ‘served with vegetables’ and ‘made from scratch’ options as healthier alternatives for their children. Parents viewed half portions of the adult’s menu as healthier alternatives to the children’s menu and considered these were of better nutritional quality.

Strategies recommended for healthier out-of-home eating

Parents, and in some cases children, discussed possible opportunities that establishments could employ to support families in making healthier food choices (Table 6). These centred around cost, flexibility of food establishments, more appropriate portion sizes for children, healthier cooking methods and marketing strategies for healthier foods.

Table 6 Potential opportunities to encourage healthier out-of-home eating suggested by samples of children (aged 5–12 years; n 96) and parents (of children aged 5–12 years; n 186) from the island of Ireland, June–August 2011

Given that parents and older children were primarily influenced by cost when eating OH, they would be more likely to consider healthier items if these were included as standard and were competitively priced against other menu items:

‘Well I think if they include it [fruit and vegetables] as part of the child’s meal then my youngest would probably eat it. But he won’t choose the fruit over the fries.’ (Parent)

‘If they stuck vegetables on the side of the plate more, it would be more normal.’ (Parent)

More flexibility was considered by parents as the most effective method of overcoming children’s food neophobia OH. Carveries, buffets and mixed platters were considered to allow children to try new foods without the concern of receiving an entire meal that they would not like:

‘But it was so annoying and I mean I got to a stage where I would say to them can I just have a plain vegetable and they would say it is already made.’ (Parent)

‘I know when my kids eat more vegetables is when we go to a buffet style. There is a lovely Chinese where they will pick the different vegetables.’ (Parent)

‘See if they done little trial bites for the children and they could taste little bits of different things that would be good because they like to taste what we are eating.’ (Parent)

Portion sizes were reported to be inconsistent between establishments and very often were too large for younger children but too small for older children. Providing a range of portion sizes for the children’s menu would allow more appropriate portions to be served to children. Both parents and children would like more establishments to offer half portions of the adult menu to increase the choice provided:

‘The 3-year-old and 8-year-old get the very same potion – a big mountain of chips and you know they’re not going to eat it and I think it’s a waste.’ (Parent)

‘If you just have your menu that reflects... a half portion of Caesar salad, half portion of spaghetti bolognaise, half portion of the roast of the day, you go in there and you would go in day after day because you get good value for money and it is education, sending out the right message to kids.’ (Parent)

‘Basically get the exact same meal [as the adult] in a smaller size right through the whole menu.’ (Parent)

Parents assumed changing current cooking methods to grilling or baking would be a small compromise for establishments to improve the nutritional quality of current children’s menus:

‘Could they have a low-fat mayonnaise option or if they suggest that they could grill it for you instead of frying, or use a different kind of oil maybe.’ (Parent)

‘I wouldn’t mind seeing something where they give you the option, would you like it fried or would you like it grilled.’ (Parent)

Current marketing strategies, such as a free toy or attractive packaging, were suggested by parents for healthier menu items to attract and encourage children to select these:

‘The way children watch TV now – they’re trying to draw them in, if they could draw them in to healthier food.’ (Parent)

‘You go into the crisps [aisle] and there are nice bright packets and in the fruit [aisle] there is just a little plastic bag over the bananas. It is not really appealing for the kids in that way, the younger ones especially.’ (Parent)

Discussion

This research has provided a unique insight into family experiences when eating OH from both parent/guardian and child perspectives. Parents believed food businesses could do more to support families to select healthier foods and highlighted potential opportunities that may improve the nutritional quality of OH food specifically targeted at children. However, improving the nutritional quality of OH food will be challenging as various issues need to be considered. Furthermore, initiatives will not be successful if the views of all relevant stakeholders are not considered.

The perception of OH eating as a treat was the most frequently mentioned factor by both parents and children. Irrespective of family demographics and what priority was placed on healthy eating in the home, health was considered less frequently in OH eating. Although ‘a treat’ may have connotations of being unhealthy, the challenge will be to ensure food that is healthier will also be perceived as a treat. There is a desire for parents to encourage their children to make healthier choices but only if the more important priorities are also met. Parents were more willing to consider health in regard to ‘quality’ of the food and believed establishments should give more focus to providing fresh meats, such as beef steak, chicken/fish fillets, as well as the more popular foods such as chicken nuggets and sausages. If the current menu items were cooked differently and were served with fruit, vegetables, yoghurt or milk, parents would view current children’s menus as healthier.

This type of approach may also resonate with the catering industry which has been found to prefer small changes that customers will not notice, such as changing cooking methods or adding fruit and vegetables as opposed to reducing portion sizes to decrease the energy density( Reference Obbagy, Condrasky and Roe 33 ). Given that children did not apply their knowledge of health and food in food choice decisions, these small by stealth changes would not detract from the enjoyment of the meal and may prove to be some of the most effective strategies. Parents also considered that children had received nutrition knowledge in school, although this did not impact upon food choice decisions. This gap between knowledge and children’s food choice decisions has been raised previously( Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon 27 , Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 28 ) and emphasises the mismatch between having the knowledge and putting it into practice.

The findings of this research are also fully supportive of Edwards, who emphasised the importance of considering not just food when eating OH but also the individual and his/her situation( Reference Edwards 39 ). Parents will sacrifice the quality of food when eating OH for a stress-free, enjoyable experience. Thus food businesses that take these needs into account, in addition to the food on offer, will be more likely to attract families as customers. Similar to Warde and Martens, the present study also demonstrated that the OH eating experience begins before entering an establishment( Reference Warde and Martens 40 ). Parents considered the best type of establishment to patronise by determining if their children would maintain interest for the occasion: if their children were likely to be disruptive in a sit-down restaurant, parents would select a child-friendly fast-food establishment with a short service time.

Clear differences were identified between what parents and children described as influencing the child’s food choice decision, with only one common theme being reported by both: ‘the norm/food neophobia’. Parents reported healthier foods in particular were likely to induce feelings of rejection in children but they believed if establishments were more willing to meet children’s special requests by being more flexible, such as avoiding any type of garnish and serving sauces separately, more children may be more likely to try new foods. Moreover, parents’ confidence in children trying new foods may need to be increased given they were more concerned with avoiding food and money waste than health considerations. Smaller portions of the adult menus would be an excellent opportunity for increasing parents’ trust that the meal will be enjoyed and promotes children eating the same foods as their parents in an environment where this tends not to happen( Reference Skafida 41 ). Parents were strongly of the opinion that marketing greatly impacted upon children’s food choice decisions, but it is interesting to note that children did not acknowledge this, as was previously shown in the home( Reference Holsten, Deatrick and Kumanyika 26 , Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 28 ) and OH settings( Reference Warren, Parry and Lynch 42 ). Parents in our study recommended using currently effective marketing techniques to promote healthier menu items in an effort to encourage children to try these, such as free toys and colourful packaging.

Given that cost is a high priority in food choice decisions by adults( Reference Ward, Mamerow and Henderson 43 –45) (and for children when purchasing their own OH food( Reference Holsten, Deatrick and Kumanyika 26 , Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 28 )), healthier foods are only likely to be selected in the OH setting if they are competitively priced. The preference was clearly for ‘all in’ pricing where a main course, side, drink and dessert were included in children’s meals. If healthier items, such as fruit and vegetables, were included in this cost it is likely that more parents will encourage children to select/consume these healthier items. However, from the food businesses’ perspective they may be reluctant to include healthier items if these are more expensive( Reference Lachat, Naska and Trichopoulou 34 ). Greater engagement with food businesses will be pivotal if they are to be persuaded to provide competitively priced healthier items without impacting overall profit margins. However, it will be of great benefit if they do to increase the family customer base.

Concurring with previous research, parents and children reported that in contrast to the home setting( Reference Holsten, Deatrick and Kumanyika 26 , Reference Warren, Parry and Lynch 42 , Reference Bassett, Chapman and Beagan 46 ), autonomy for choosing OH food begins at a much younger age( Reference Fitzgerald, Heary and Nixon 27 , Reference Warren, Parry and Lynch 42 ). As a result, any efforts to encourage children to make healthier choices should be cognisant of the fact that children make food choices based predominantly on taste( Reference Holsten, Deatrick and Kumanyika 26 – Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry 29 , Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett 47 ). However, children’s food choice decisions are even more complex in the OH environment given that while children have increased autonomy in the decision made, the process is bidirectional with parents. This highlights how imperative it is to consider both parents’ and children’s competing priorities in a public health intervention aimed at supporting healthier OH choices.

The main strength of this research has been the exploration of issues concerned with OH eating from both the parent’s and child’s perspective, and from a wide range of backgrounds across the island of Ireland. However, there are also acknowledged limitations. Although purposive sampling techniques were used to recruit participants in the interest of generating a rich data set, the study participants may not have been representative of the general population. The inclusion of a large number of discussion topics for parents and children may not have achieved a full exploration of each discussion topic but it has provided a good overview of the factors influencing current family OH eating practices.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the family OH eating environment is a unique and increasingly a key part of the food environment. At present OH eating occasions are largely perceived as a treat for all the family where although parents would like to consider health, it is not currently a priority for many parents and children. However, there are potential opportunities for food businesses to support families to make healthier decisions which will only serve to increase an establishment’s attractiveness to families. The key changes highlighted by parents and children that may be most effective were increased choice, increased flexibility and a change to healthier cooking methods. Training for food businesses to create interesting, appealing and economically viable menu items that maintain the treat element of the occasion will be important to ensure the success of healthier OH eating. Of upmost importance, the entire family OH experience needs to be considered when developing public health interventions as these will not be effective if they do not acknowledge family priorities and expectations in this environment.

Acknowledgements

The authors dedicate this article to the memory of their colleague Professor Julie Wallace (7 April 1971–7 February 2012). Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the parents and children who participated in the study and to Nick Bohill (N.B.) and Dawn McCartney (D.M.) for their contribution towards moderating the pairs and groups. Financial support: This material is based upon works supported by safefood, the Food Safety Promotion Board (under grant number 10-2009). L.E.M. is supported by a PhD award from the Department of Employment and Learning, UK. safefood and the Department of Employment and Learning had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: M.B.E.L., J.M.W.W., G.H. and A.L designed the study. G.H. and A.L. recruited participants and conducted the research. L.E.M. and R.K.P. attended qualitative sessions as note takers. L.E.M. and R.K.P. analysed the data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. T.A.M., G.H. and A.L. critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. M.B.E.L. led the research and finalised the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The research was approved by the University of Ulster Research Ethics Committee (REC/11/0057).