Introduction

Childhood adversity is a serious public health issue with high global prevalence and lifelong negative impact on individuals' health and well-being. Furthermore, its effects cut across generations. Childhood adversity is commonly defined as an exposure to any type of physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse or neglect that occurred before 18 years of age (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos2012). It is estimated that every year millions of children suffer from different forms of abuse and neglect (Afifi & MacMillan, Reference Afifi and MacMillan2011), with a worldwide prevalence ranging between 12.7% and 26.7% (Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, Reference Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2013; Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Alink, & Van Ijzendoorn, Reference Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Alink and Van Ijzendoorn2012; Stoltenborgh, Van Ijzendoorn, Euser, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, Reference Stoltenborgh, Van Ijzendoorn, Euser and Bakermans-Kranenburg2011). As adults, individuals with a history of childhood adversity may be more likely to have children who also experience adversity (Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Cyr, Eirich, Fearon, Ly, Rash and Alink2019). A history of maternal childhood adversity (MCA, i.e. adversities experienced by mothers when they were children) in particular has been associated with the presence of depression, internalising and externalising problems in their children (Myhre, Dyb, Wentzel-Larsen, Grogaard, & Thoresen, Reference Myhre, Dyb, Wentzel-Larsen, Grogaard and Thoresen2014; Su, D'Arcy, & Meng, Reference Su, D'Arcy and Meng2022). This evidence suggests that childhood adversity can lock successive generations of families into poorer health outcomes and a vulnerability to behavioural and mental health problems.

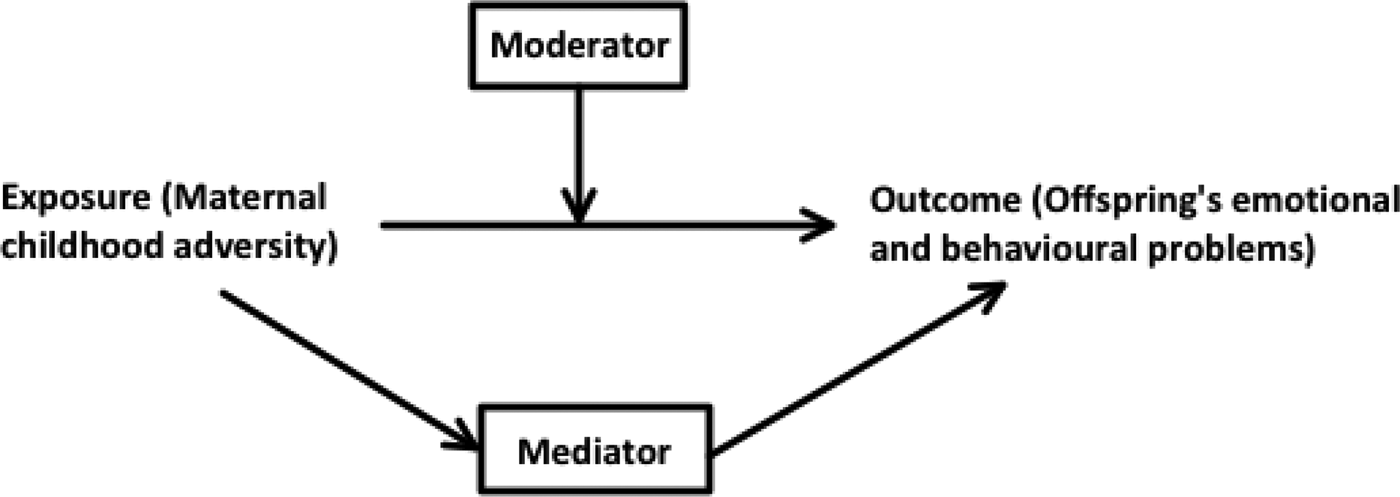

Exploring mediators and moderators in the link between MCA and their children's outcomes is important in clinical prevention, as interventions can precisely target these factors to help improve health outcomes. Mediators are variables that act on the causal pathway between the exposure and outcome, which is influenced by the exposure and in turn influences the outcome, while moderators can affect the direction or strength of the relation between the exposure and the outcome. A significant body of research has investigated the potential mediators underlying the pathway between mothers' experiences of childhood adversity and adverse emotional and behavioural development in their children. These have included maternal individual characteristics, such as maternal mental health problems (Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim, & Short, Reference Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim and Short2013; Myhre et al., Reference Myhre, Dyb, Wentzel-Larsen, Grogaard and Thoresen2014; Plant, Barker, Waters, Pawlby, & Pariante, Reference Plant, Barker, Waters, Pawlby and Pariante2013), and family nurturing factors consisting of maternal hostility (Rijlaarsdam et al., Reference Rijlaarsdam, Stevens, Jansen, Ringoot, Jaddoe, Hofman and Tiemeier2014), harsh parenting discipline (Rijlaarsdam et al., Reference Rijlaarsdam, Stevens, Jansen, Ringoot, Jaddoe, Hofman and Tiemeier2014; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Cederbaum, Mennen, Traube, Chou and Lee2019), maternal social support (Bosquet Enlow, Englund, & Egeland, Reference Bosquet Enlow, Englund and Egeland2018; Min et al., Reference Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim and Short2013) and their own children's experience of early adversity (Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen, & Alan Sroufe, Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Alan Sroufe2005; Herrenkohl & Herrenkohl, Reference Herrenkohl and Herrenkohl2007). On the other hand, potential moderators affecting the strength of the relationship between MCA and children's emotional and behavioural development have also been identified. These moderators include maternal mental health (Bouvette-Turcot et al., Reference Bouvette-Turcot, Fleming, Wazana, Sokolowski, Gaudreau, Gonzalez and Meaney2015; Isosavi et al., Reference Isosavi, Diab, Kangaslampi, Qouta, Kankaanpaa, Puura and Punamaki2017; Miranda, de la Osa, Granero, & Ezpeleta, Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2011), child biological characteristics (Bouvette-Turcot et al., Reference Bouvette-Turcot, Fleming, Wazana, Sokolowski, Gaudreau, Gonzalez and Meaney2015; van de Ven, van den Heuvel, Bhogal, Lewis, & Thomason, Reference van de Ven, van den Heuvel, Bhogal, Lewis and Thomason2020; Villani et al., Reference Villani, Ludmer, Gonzalez, Levitan, Kennedy, Masellis and Atkinson2018), child sex (Linde-Krieger & Yates, Reference Linde-Krieger and Yates2018; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Cederbaum, Mennen, Traube, Chou and Lee2019) and parenting practices (Meller, Kuperman, McCullough, & Shaffer, Reference Meller, Kuperman, McCullough and Shaffer2016; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2011). However, whether these mediators or moderators consistently play a significant role in the association between MCA and children's emotional and behavioural development remains to be established.

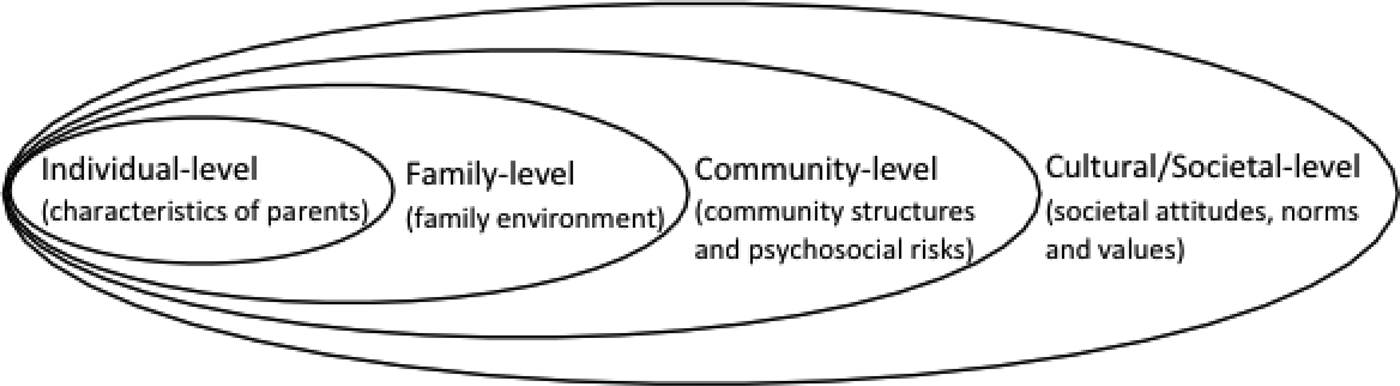

To systematically synthesise these factors, we adopted an approach based on the ecological framework of child maltreatment (Belsky, Reference Belsky1980) and on the intergenerational transmission of childhood abuse (Langeland & Dijkstra, Reference Langeland and Dijkstra1995) (Fig. 1). This categorises health determinants into four different levels (individual, family, community and societal levels) which can be used to identify vulnerable populations and to inform specific multi-level interventions (Egan, Tannahill, Petticrew, & Thomas, Reference Egan, Tannahill, Petticrew and Thomas2008; Sidebotham & Heron, Reference Sidebotham and Heron2006; Wold & Mittelmark, Reference Wold and Mittelmark2018). Since there are no reviews that have comprehensively synthesised or quantified the evidence on the mediators and moderators linking MCA and children's mental health at multiple levels, this review is timely and needed. Evaluating the possible pathways linking maternal adversity and child outcomes with a systematic and quantitative approach would also help delineate the key processes involved, and help identifying the most vulnerable individuals who could benefit from interventions that break the transmission from MCA to adverse outcomes in children.

Fig. 1. The ecological framework for understanding the link between maternal childhood adversity and their children's mental health development.

This review aims to provide a narrative synthesis of existing literature to identify the mediators and moderators that regulate the association between MCA and adverse emotional and behavioural development in children. Furthermore, it aims to investigate the magnitude of any mediating effect by providing a quantitative meta-synthesis.

Methods

The process of this systematic review and meta-analysis was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement (Yepes-Nuñez, Urrútia, Romero-García, & Alonso-Fernández, Reference Yepes-Nuñez, Urrútia, Romero-García and Alonso-Fernández2021). Furthermore, all results were reported based on the categories in an ecological framework (Fig. 1).

Study search

Systematic searches of peer-reviewed papers in EMBASE, PsycINFO, Medline and the Cochrane Library were conducted up to 26th of February 2021, using a combination of controlled terms and keywords (online Supplementary Appendix A). Systematic searches of grey literature (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Hillier-Brown, Moore, Lake, Araujo-Soares, White and Summerbell2016) were also conducted to identify unpublished articles and documents using search engines, including OpenGrey and WorldCat. Reference lists of included articles were searched and reviewed. Searches were restricted to studies using human participants and written in English, with no restriction on publication year.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) used an observational study design (i.e. cohort, cross-sectional and case–control studies); (2) examined the association between a history of childhood adversity in the mother (including biological mothers and step-mothers as the primary caregiver), at least one form of either physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional/psychological abuse and neglect that occurred before 18 years of age) and their children's emotional and behavioural outcomes [either emotional or behavioural development by age 18 years, including internalising problems, externalising problems, antisocial behaviours, conduct problems, emotional and behavioural dysregulation, depression, anxiety, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)]; and (3) quantitatively analysed at least one mediator or moderator in the association between MCA and children's outcomes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The conceptualisation of the mediator and moderator relationships illustrated by a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). Moderator: A variable that affects the direction/or strength of the relation between the exposure and outcome. Mediator: A variable on the causal pathway between the exposure and outcome, which is influenced by the exposure and in turn influences the outcome.

We excluded: (1) reviews, meta-analyses, conference abstracts, book chapters or incomplete articles; (2) qualitative studies.

Screening and data extraction

Abstracts and articles for inclusion were double-screened by XM and AB. Upon completion of the initial search, studies were exported to Excel and screened independently by XM and AB to establish reliability and to ensure that no relevant studies were missed. PD and CN were consulted to reach consensus where necessary. For the meta-analysis, effect sizes were extracted by XM, with 10% extracted by CS independently, to ensure accuracy. Effect sizes were indirect standardised effect (β) and variance (square of the standard error of β) in all mediation models in each study. Where appropriate data were not available, these were calculated using available data in the paper and further requests were sent to study authors. Ultimately, 781 articles' abstracts were screened, and 74 full-text articles were then screened. After review and discussion of discrepancies, 41 studies were selected for the final review and five for the meta-analysis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review and meta-analysis processes.

Strategy for data synthesis

The narrative synthesis provides a detailed account of the samples and study designs, the types and measures of MCA, children's outcomes and measures, the mediating and/or moderating factors in the association between MCA and children's outcomes. We systematically synthesise mediators and moderators at the (1) individual level (maternal characteristics), (2) family level (family relationship, including parenting practices, interaction between parents and child, and domestic violence) and (3) community (psychosocial factors) and societal (societal attitudes and values) level, based on an ecological framework (Fig. 1).

The quantitative meta-analyses were run in R (version 3.6.3), after excluding studies with an insufficient number of consistent outcomes or with incomplete data (Fig. 3). Nine single-mediating analyses were identified and separate meta-analyses were conducted on three mediating pathways: (1) maternal depression; (2) negative parenting practices; and (3) maternal insecure attachment. We used parameter-based meta-analytic structural equation modelling (MASEM) to synthesise the mediation analysis after extracting the indirect effects reported, or computing the indirect effects from the correlation matrices of the primary studies, as well as estimating sampling variances (Cheung, Reference Cheung2022). Afterwards, we used the metaSEM packages to calculate the pooled indirect effects and used restricted maximum likelihood (REML) to estimate parameters in random-effect models (Cheung, Reference Cheung2015). The degree of heterogeneity was assessed by τ 2, which is the heterogeneity variance of the random effects (Borenstein, Higgins, Hedges, & Rothstein, Reference Borenstein, Higgins, Hedges and Rothstein2017). All p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scales for case–control, cohort and cross-sectional studies (Madhavan, Lagorio, Crary, Dahl, & Carnaby, Reference Madhavan, Lagorio, Crary, Dahl and Carnaby2016; Moskalewicz & Oremus, Reference Moskalewicz and Oremus2020) were used to assess study quality, based on selection, comparability and exposure/outcome (online Supplementary Table S1). A score ⩾7 indicates a good quality study and scores 5–6 indicate a satisfactory quality study (Herzog et al., Reference Herzog, Álvarez-Pasquin, Díaz, Del Barrio, Estrada and Gil2013). Scores ranged from 5 to 8, indicating a satisfactory quality for all studies included in the review (online Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

Results

Forty-one eligible studies were identified, including 11 cross-sectional studies, 3 case–control studies and 27 longitudinal cohort studies (Fig. 3, Table 1). Most studies were published from 2011 onwards (n = 36, 90%), with most conducted in North America (n = 25, 61%) and Europe (n = 11, 27%), with sample sizes ranging from 45 to 109 758 mother–child dyads. While most studies were population-based, such as the Nurse's Health Study II (Roberts, Liew, Lyall, Ascherio, & Weisskopf, Reference Roberts, Liew, Lyall, Ascherio and Weisskopf2018; Roberts, Lyall, & Weisskopf, Reference Roberts, Lyall and Weisskopf2017; Roberts, Lyall, Rich-Edwards, Ascherio, & Weisskopf, Reference Roberts, Lyall, Rich-Edwards, Ascherio and Weisskopf2013), the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) (Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn, Golding, & Team, Reference Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn, Golding and Team2004) and Generation R (Rijlaarsdam et al., Reference Rijlaarsdam, Stevens, Jansen, Ringoot, Jaddoe, Hofman and Tiemeier2014), there were also studies from specific populations, including four from children attending psychiatric outpatient services (Bodeker et al., Reference Bodeker, Fuchs, Fuhrer, Kluczniok, Dittrich, Reichl and Resch2019; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2011, Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2013a, Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2013b), six from low-income families (Bosquet Enlow et al., Reference Bosquet Enlow, Englund and Egeland2018; McDonnell & Valentino, Reference McDonnell and Valentino2016; Min et al., Reference Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim and Short2013; Russotti, Warmingham, Handley, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, Reference Russotti, Warmingham, Handley, Rogosch and Cicchetti2021; Thompson, Reference Thompson2007; Warmingham, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, Reference Warmingham, Rogosch and Cicchetti2020), and two including teenage mothers (Pasalich, Cyr, Zheng, McMahon, & Spieker, Reference Pasalich, Cyr, Zheng, McMahon and Spieker2016; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Cederbaum, Mennen, Traube, Chou and Lee2019). The most common instruments used to evaluate children's outcomes were the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach, Kreutzer, DeLuca and Caplan2011; McConaughy, Reference McConaughy, Andrews, Saklofske and Janzen2001) (n = 19, 46%) and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, Reference Goodman1997) (n = 6, 15%), while the most commonly used measure for MCA was the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein, Fink, Handelsman, & Foote, Reference Bernstein, Fink, Handelsman and Foote1998) (n = 18, 44%).

Table 1. Characteristics of eligible studies included in this review, grouped by study design

Note: *Significant factors.

Mediators

Individual-level mediators

Individual-level mediators included maternal depression, anxiety, and perinatal health.

The mediating role of maternal mental health was reported in several studies, with more evidence for a role of depression than anxiety. We identified 10 longitudinal studies that reported that children of mothers exposed to childhood adversity were more likely to develop emotional-behavioural problems than children of mothers who were not exposed to MCA, with 6–45% of the total effects being mediated by postnatal depression (Bouvette-Turcot et al., Reference Bouvette-Turcot, Fleming, Unternaehrer, Gonzalez, Atkinson, Gaudreau and Meaney2020; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Sikkema, Vythilingum, Geerts, Faure, Watt and Stein2017; Giallo et al., Reference Giallo, Gartland, Seymour, Conway, Mensah, Skinner and Brown2020; Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, & Jenkins, Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon and Jenkins2015; Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire, & Jenkins, Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire and Jenkins2017; Min et al., Reference Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim and Short2013; Myhre et al., Reference Myhre, Dyb, Wentzel-Larsen, Grogaard and Thoresen2014; Pereira, Ludmer, Gonzalez, & Atkinson, Reference Pereira, Ludmer, Gonzalez and Atkinson2018; Plant, Jones, Pariante, & Pawlby, Reference Plant, Jones, Pariante and Pawlby2017; Zvara, Mills-Koonce, Carmody, & Cox, Reference Zvara, Mills-Koonce, Carmody and Cox2017). Of note, one study reported that both maternal antenatal and postnatal depression independently mediated the relationship between MCA and children's emotional-behavioural problems, with 20 and 6% of the total effects on child internalising behaviours, and 14 and 37% on child externalising behaviours being explained by antenatal and postnatal depression respectively (Plant et al., Reference Plant, Jones, Pariante and Pawlby2017). On the other hand, four cross-sectional studies suggested that current maternal depression positively fully or partially mediated the pathway from MCA to child problems, such as anxiety and depression, and rule-breaking and aggressive behaviours (Meller et al., Reference Meller, Kuperman, McCullough and Shaffer2016; Miranda, de la Osa, Granero, & Ezpeleta, Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2013a, Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2013b; Russotti et al., Reference Russotti, Warmingham, Handley, Rogosch and Cicchetti2021), and one study suggested that maternal depression throughout life, rather than postnatal depression, played a mediating role beyond the postpartum period (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Houts, Arseneault, Pariante, Sikkema and Moffitt2019).

Only two studies assessed maternal anxiety as an independent mediator and three included maternal anxiety in the assessment. Among these, three indicated that maternal mental distress, including anxiety significantly mediated the association between MCA and the presence of children's internalising and externalising problems (Min et al., Reference Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim and Short2013; Myhre et al., Reference Myhre, Dyb, Wentzel-Larsen, Grogaard and Thoresen2014; Oshio & Umeda, Reference Oshio and Umeda2016), and the UK ALSPAC study suggested that maternal postnatal anxiety rather than depression independently mediated 16% of the relationship between maternal childhood sexual abuse and poorer child emotional-behavioural adjustment at age 47 months (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn, Golding and Team2004). However, another cross-sectional study conducted among psychiatric outpatient children in Spain found the opposite result, suggesting that maternal postpartum depression rather than anxiety mediated the relationship between MCA and child externalising behaviour in 8- to 17-year-old youths (Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2013a). It is possible that maternal anxiety is associated with mental health problems in young children, while maternal depression could have more influence on adolescent mental health.

By contrast, seven studies did not support the presence of a mediating role for any type of maternal mental health problems in the relationship between MCA and child (Bosquet Enlow et al., Reference Bosquet Enlow, Englund and Egeland2018; Esteves, Gray, Theall, & Drury, Reference Esteves, Gray, Theall and Drury2017; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2011; Thompson, Reference Thompson2007; Warmingham et al., Reference Warmingham, Rogosch and Cicchetti2020) or infant emotional-behavioural problems (Isosavi et al., Reference Isosavi, Diab, Kangaslampi, Qouta, Kankaanpaa, Puura and Punamaki2017; McDonnell & Valentino, Reference McDonnell and Valentino2016). Interestingly, six of these studies included participants from low-income or high-risk neighbourhoods, suggesting that lower socioeconomic circumstances may modify the mediating effect of maternal mental health problems.

Only four studies investigated the role of maternal perinatal health as a mediator. One study suggested that gestational diabetes, abortion history and smoking during pregnancy significantly mediated 3.5, 3.0 and 2.5% respectively, of the association between MCA and an increased risk of their children's autism (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Lyall, Rich-Edwards, Ascherio and Weisskopf2013), while another study did not find perinatal risk factors to be mediators for ADHD (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Liew, Lyall, Ascherio and Weisskopf2018). Furthermore, maternal adolescent childbearing, their children's preterm birth or low birth weight were not significant mediators in the relationship between MCA and children's emotional-behavioural difficulties (Giallo et al., Reference Giallo, Gartland, Seymour, Conway, Mensah, Skinner and Brown2020; Russotti et al., Reference Russotti, Warmingham, Handley, Rogosch and Cicchetti2021).

Family-level mediators

Family-level mediators included child traumatic experiences, negative and positive parenting practices, maternal–child attachment, and intimate partner violence.

Notably, traumatic experiences in the children themselves have been posited as mediators in the link between MCA and child emotional-behavioural problems, with eight out of nine studies that investigated this factor reporting its significant role in mediating 17–47% of the total effects (Bosquet Enlow et al., Reference Bosquet Enlow, Englund and Egeland2018; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Houts, Arseneault, Pariante, Sikkema and Moffitt2019; Collishaw, Dunn, O'Connor, & Golding, Reference Collishaw, Dunn, O'Connor and Golding2007; Miranda, de la Osa, Granero, & Ezpeleta, Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2013b; Plant et al., Reference Plant, Barker, Waters, Pawlby and Pariante2013; Plant et al., Reference Plant, Jones, Pariante and Pawlby2017; Russotti et al., Reference Russotti, Warmingham, Handley, Rogosch and Cicchetti2021; Warmingham et al., Reference Warmingham, Rogosch and Cicchetti2020). Only one cross-sectional study, conducted among 101 predominantly African–American mother–child dyads living in high-risk neighbourhoods in the United States, did not report this link (Esteves et al., Reference Esteves, Gray, Theall and Drury2017), suggesting that socioeconomic deprivation may have attenuated the mediating effect of child traumatic experiences.

Parenting practices, both negative and positive, have been the most frequently investigated family-level mediators in the relationship between MCA and children's emotional-behavioural problems. Evidence is inconsistent for the role of negative parenting practices, with two longitudinal population-based studies indicating these significantly mediated 15–70% of the total effect (Rijlaarsdam et al., Reference Rijlaarsdam, Stevens, Jansen, Ringoot, Jaddoe, Hofman and Tiemeier2014; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Cederbaum, Mennen, Traube, Chou and Lee2019). However, two studies in psychiatric outpatient settings, and one in a deprived community sample did not find any effect for harsh parenting discipline (Esteves et al., Reference Esteves, Gray, Theall and Drury2017; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2011, Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2013b). Five studies investigated the potential mediating effect of maternal hostility as a negative parenting mediator. Of these, two suggested this played a significant mediating role (Collishaw et al., Reference Collishaw, Dunn, O'Connor and Golding2007; Rijlaarsdam et al., Reference Rijlaarsdam, Stevens, Jansen, Ringoot, Jaddoe, Hofman and Tiemeier2014), while the other three studies did not (Bosquet Enlow et al., Reference Bosquet Enlow, Englund and Egeland2018; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2013a; Pasalich et al., Reference Pasalich, Cyr, Zheng, McMahon and Spieker2016). Of note, these studies used different measures to define maternal hostility, which could explain discrepancies in findings.

Similarly, findings are inconsistent on the role of positive parenting practices. Among the studies included, one community-based longitudinal study in the United States suggested maternal sensitive parenting practice significantly reduced the link between maternal childhood sexual trauma and child conduct problems (Zvara et al., Reference Zvara, Mills-Koonce, Carmody and Cox2017), whereas two studies conducted in Germany and Canada respectively only found its mediating protective effect between maternal depression and child emotional-behavioural development (Bodeker et al., Reference Bodeker, Fuchs, Fuhrer, Kluczniok, Dittrich, Reichl and Resch2019; Bouvette-Turcot et al., Reference Bouvette-Turcot, Fleming, Unternaehrer, Gonzalez, Atkinson, Gaudreau and Meaney2020). Furthermore, the UK ALSPAC study found that a mother's higher confidence in her relationship with her child negatively mediated 13% of the total effects of maternal childhood sexual abuse on their children's emotional-behavioural problems (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn, Golding and Team2004), while a longitudinal study in Canada found responsive parenting not to significantly mediate the association between MCA and child internalising behaviour (Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon and Jenkins2015).

Attachment styles are patterns of interactions in intimate relationships (Widom, Czaja, Kozakowski, & Chauhan, Reference Widom, Czaja, Kozakowski and Chauhan2018), and thus important family-level factors at theoretical and practical level. Among the three studies investigating the role of maternal–child attachment in the pathway between MCA and children's emotional-behavioural development, two found that maternal avoidant attachment (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Ludmer, Gonzalez and Atkinson2018) and insecure infant attachment (Pasalich et al., Reference Pasalich, Cyr, Zheng, McMahon and Spieker2016) significantly mediated 35 and 64% of the association between MCA and child externalising problems, while the other study indicated that maternal secure attachment was protective, and mediated 31% of the total effect between MCA and child total behavioural problems (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Humphreys, King, Mondal, Gotlib and Robakis2021).

Another important family-level factor is intimate partner violence, which was investigated as a potential mediator in four studies (Giallo et al., Reference Giallo, Gartland, Seymour, Conway, Mensah, Skinner and Brown2020; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Lyall and Weisskopf2017, Reference Roberts, Liew, Lyall, Ascherio and Weisskopf2018; Zvara et al., Reference Zvara, Mills-Koonce, Carmody and Cox2017). One of these found that postpartum exposure to intimate partner violence mediated 16% of the total effect between MCA and child emotional-behavioural problems (Giallo et al., Reference Giallo, Gartland, Seymour, Conway, Mensah, Skinner and Brown2020), while one study only found it mediated 24% of the total effect between maternal childhood sexual trauma and sensitive parenting (Zvara et al., Reference Zvara, Mills-Koonce, Carmody and Cox2017). However, two population-based case–control studies did not find intimate partner violence to be a mediator between MCA and child ASD or ADHD (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Lyall and Weisskopf2017, Reference Roberts, Liew, Lyall, Ascherio and Weisskopf2018).

Community and Societal- level mediators

Only six studies reported on community factors (social support and psychosocial risks) and no studies on societal factors.

Although social support is generally accepted to be a protective factor for mental health (Wang, Mann, Lloyd-Evans, Ma, & Johnson, Reference Wang, Mann, Lloyd-Evans, Ma and Johnson2018), only three studies investigated the mediating role of maternal perceived social support, with one study finding this to be a significant protective mediator (β = 0.06, 95% CI 0.01–1.15) in primarily poor African–American mother–child dyads (Min et al., Reference Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim and Short2013), and the other two studies suggesting its role was non-significant (Bosquet Enlow et al., Reference Bosquet Enlow, Englund and Egeland2018; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Ludmer, Gonzalez and Atkinson2018). For infants, a longitudinal study found that the relationship between MCA and infant emotional health was mediated by cumulative psychosocial risks (β = 0.037, 95% CI 0.001–0.056), including being a single parent, being a teenage mother, having low family income, low maternal education and marital conflict (Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire and Jenkins2017). However, two studies conducted in a large-scale cohort and in a low-income community sample did not find socio-economic circumstances to be significant mediators between MCA and children's ADHD or total behavioural problems, including social withdrawal, anxiety/depression and aggressive behaviour (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Liew, Lyall, Ascherio and Weisskopf2018; Thompson, Reference Thompson2007).

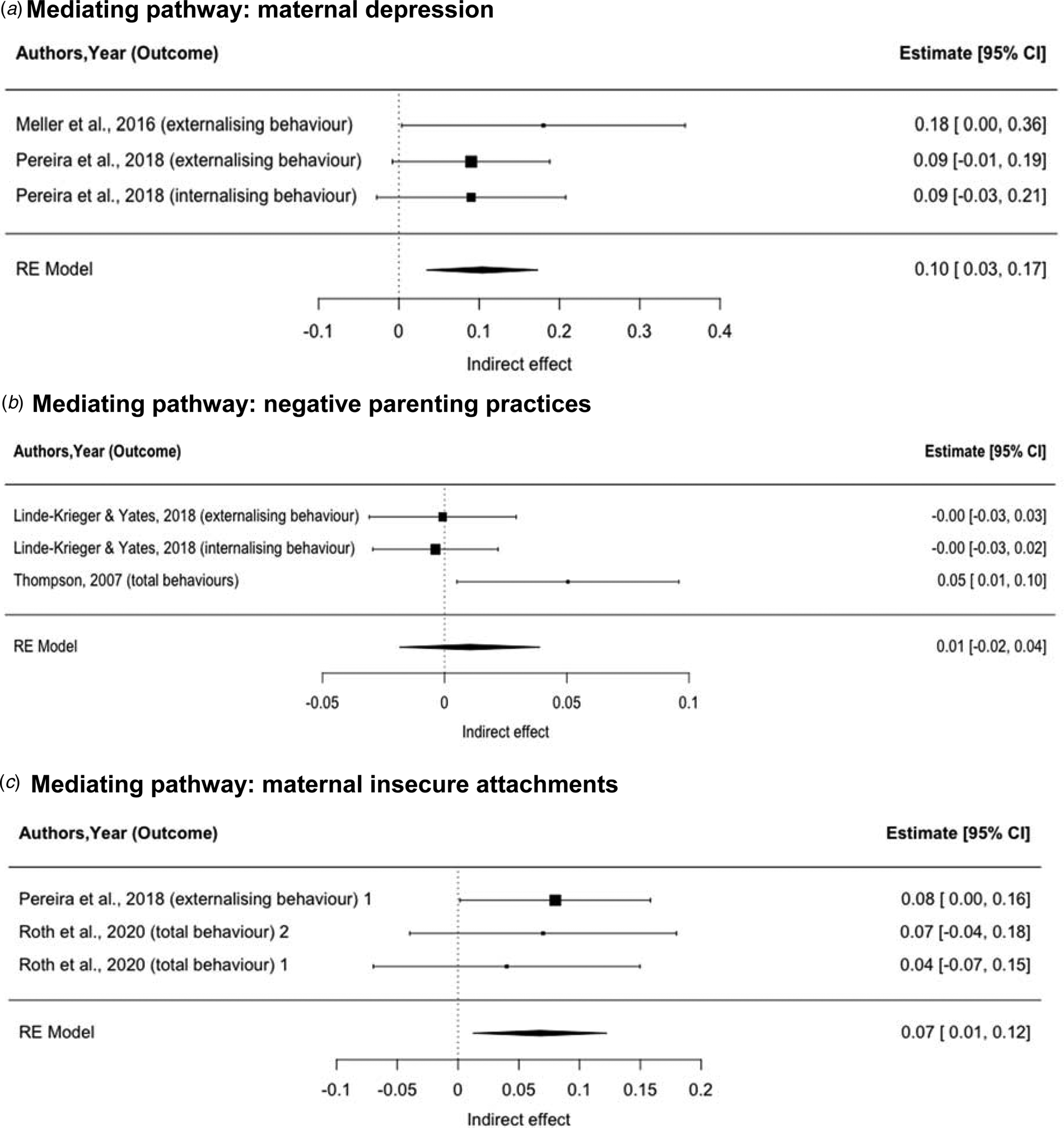

Meta-analysis of single-mediator analyses

To limit heterogeneity of findings and ensure reliability, we limited the meta-analysis to studies that assessed emotional and behavioural development in terms of externalising behaviours, internalising behaviours and emotional-behavioural difficulties, assessed using the CBCL and the SDQ. The meta-analysis was therefore conducted on nine single-mediator pathway analyses with complete coefficients (Fig. 3). The standardised indirect effect estimates (βs) were 0.10 (95% CI 0.03–0.17) for an individual-level mediating pathway (maternal depression), 0.01 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.04) for a family-level mediating pathway (negative parenting practices) and 0.07 (95% CI 0.01–0.12) for a family-level mediating pathway (maternal insecure attachment) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, 47 and 25% of the total effect of MCA on child behaviours could be mediated by maternal depression and maternal insecure attachments, respectively (online Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 4. Pooled indirect effects of mediating pathways between maternal childhood adversity and their children's emotional and behavioural problems. (a) Mediating pathway: maternal depression. (b) Mediating pathway: negative parenting practices. (c) Mediating pathway: maternal insecure attachments.

Note: 1 Mediator: avoidant maternal attachment; 2 Mediator: anxious maternal attachment.

Moderators

Individual-level moderators

Individual-level moderators included maternal mental health, child sex, biological and genetic factors.

In contrast to its significant mediating role discussed above, two studies reported a non-significant moderating effect of maternal mental health in the association between MCA and children's (Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2011) or infants' emotional and behavioural dysregulation (Bouvette-Turcot et al., Reference Bouvette-Turcot, Fleming, Wazana, Sokolowski, Gaudreau, Gonzalez and Meaney2015). However, a study conducted in the Gaza Strip found that maternal exposure to war trauma acted as a moderator between maternal childhood emotional abuse and infant negative affectivity, with a significant interaction for maternal childhood emotional abuse X war trauma (β = −0.21, p = 0.002) (Isosavi et al., Reference Isosavi, Diab, Kangaslampi, Qouta, Kankaanpaa, Puura and Punamaki2017). A tentative explanation is that high war trauma could blur the maternal perception of their infants' characteristics, as the results of this study were based on maternal ratings of infants' behaviours. Additionally, for adolescent antisocial behaviour, one study found maternal antenatal depression could strengthen the association between MCA and child antisocial behaviours (Plant et al., Reference Plant, Barker, Waters, Pawlby and Pariante2013).

The most frequently investigated moderator in the relationship between MCA and children's emotional-behavioural problems was child sex. Four of the six studies that tested the moderating effect of child sex did not find any sex difference in the association between MCA and child behaviours (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Houts, Arseneault, Pariante, Sikkema and Moffitt2019; Min et al., Reference Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim and Short2013; Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2013a; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Lyall, Rich-Edwards, Ascherio and Weisskopf2013). However, using moderated mediation and multi-group analyses, the other two studies revealed a sex difference in the mediating pathway of parenting practice between MCA and child externalising behaviour, with the mediating effect of parenting practises being only significant for girls (Linde-Krieger & Yates, Reference Linde-Krieger and Yates2018; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Cederbaum, Mennen, Traube, Chou and Lee2019). These findings suggest that girls may be more sensitive than boys to parenting practices in their emotional and behavioural development.

Other biological and genetic moderators were reported in four studies, including infant serotonin-transporter-linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR), dopamine transporter solute carrier family C6, member 4 (SLC6A3), and catechol- O-methyltransferase (COMT) genes, maternal oxytocin receptor (OXTR, rs53576) genotype and maternal cortisol levels (Bouvette-Turcot et al., Reference Bouvette-Turcot, Fleming, Wazana, Sokolowski, Gaudreau, Gonzalez and Meaney2015; Ludmer et al., Reference Ludmer, Gonzalez, Kennedy, Masellis, Meinz and Atkinson2018; Villani et al., Reference Villani, Ludmer, Gonzalez, Levitan, Kennedy, Masellis and Atkinson2018), as well as child frontal alpha wave asymmetry (van de Ven et al., Reference van de Ven, van den Heuvel, Bhogal, Lewis and Thomason2020). These moderators were suggested to interact with MCA, further affecting both infant and child emotional-behavioural dysregulation, such as negative emotionality, behavioural dysregulation and mother-infant disorganised attachment.

Family-level moderators

Only two studies tested the moderating role of negative parenting practices. A small cross-sectional study found that the mediating effect of maternal postpartum depression was stronger among mothers with high levels of maternal hostility compared to mothers with low levels of maternal hostility (Meller et al., Reference Meller, Kuperman, McCullough and Shaffer2016). By contrast, another cross-sectional study in mothers from psychiatric outpatient settings did not find harsh parenting discipline to be a significant moderator in the relationship between MCA and child internalising or externalising behaviours (Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta2011).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive systematic review of mediators and moderators in the relationship between maternal childhood adversity and the emotional-behavioural development of their children, and this is also the first meta-analysis of mediating pathways in this link. Our review shows that maternal mental health, child traumatic experiences and insecure maternal–child attachment are consistent mediators. Our meta-analysis also confirms two significant mediating pathways: maternal depression and maternal insecure attachment. However, we found limited evidence on the mediating role of community-level factors, especially societal and cultural factors, pointing to an important research gap in this area. This is further compounded by the fact that the only few studies identified predominantly investigated the moderating role of biological and genetic factors, with no comprehensive evaluation of psychosocial factors.

Maternal depression was confirmed as a key mediator in the relationship between MCA and child emotional-behavioural problems. Notably, multiple studies have found that depression occurring in the first three years postpartum is a significant mediator, highlighting the importance of good maternal perinatal mental health throughout infants' childhood. Interestingly, evidence from low-income communities indicates that mothers with more depressive symptoms might be more likely to use restrictive management strategies to keep children safe from harm (Gutman, Friedel, & Hitt, Reference Gutman, Friedel and Hitt2003), suggesting that negative parenting practices, might overtake any potential mediating role for maternal depression. Previous studies also found evidence that the relationship between maternal depression and children's externalising symptoms is partially negatively mediated by the maternal level of positivity in the interaction with her child (Ewell Foster, Garber, & Durlak, Reference Ewell Foster, Garber and Durlak2008). However, the negative impact of experiencing socioeconomic deprivation can also play a significant role in the emotional and behavioural development of the child, masking any specific effect of poor maternal mental health.

A maternal insecure attachment was confirmed as another significant mediator in the association between MCA and child internalising and externalising problems. Adult attachment styles are patterns of interactions in intimate relationships throughout adulthood, developed from expectations and responses to interpersonal events in early childhood relationships (Widom et al., Reference Widom, Czaja, Kozakowski and Chauhan2018), and are influenced by childhood adversity and family environment. More research would help establish whether other mediators co-occur with maternal attachment in this pathway.

Interestingly, our meta-analysis suggests that negative parenting practices do not significantly mediate the association between MCA and child emotional-behavioural problems (Esteves et al., Reference Esteves, Gray, Theall and Drury2017; Linde-Krieger & Yates, Reference Linde-Krieger and Yates2018; Thompson, Reference Thompson2007). Importantly, child sex may moderate the mediating role of negative parenting practices, being more evident in girls than in boys (Linde-Krieger & Yates, Reference Linde-Krieger and Yates2018; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Cederbaum, Mennen, Traube, Chou and Lee2019). This points to the potential value of sex-specific interventions if these findings are replicated. Of note, studies that did not find a significant moderating effect of child sex did not evaluate parenting practices as mediators. Girls may be particularly sensitive to parenting styles and negative events occurring in the family context, by virtue of their tendency to have a closer relationship with their families (Smith Leavell & Tamis-LeMonda, Reference Smith Leavell, Tamis-LeMonda and Fincham2013). Also, sex differences may be due to different biological responses to childhood stressors, as some evidence suggests that girls have a stronger cortisol response to childhood stressors (Hollanders, van der Voorn, Rotteveel, & Finken, Reference Hollanders, van der Voorn, Rotteveel and Finken2017).

By contrast, only few studies investigated positive parenting, pointing to maternal confidence in her relationship with her child as a significant protective mediator (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn, Golding and Team2004), while findings on responsive/sensitive parenting were inconsistent (Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon and Jenkins2015; Zvara et al., Reference Zvara, Mills-Koonce, Carmody and Cox2017). Of note, converging evidence from both intervention trials and observational longitudinal studies suggests that, at least in early childhood, positive rather than negative parenting may be a developmentally more important predictor of child problem behaviours (Gardner, Hutchings, Bywater, & Whitaker, Reference Gardner, Hutchings, Bywater and Whitaker2010; Gardner, Shaw, Dishion, Burton, & Supplee, Reference Gardner, Shaw, Dishion, Burton and Supplee2007; Gardner, Sonuga-Barke, & Sayal, Reference Gardner, Sonuga-Barke and Sayal1999). Interestingly, a recent study found that responsive parenting acted as a moderator mitigating the ill effects of maternal posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms on children's depression and stress-related symptoms (Greene, McCarthy, Estabrook, Wakschlag, & Briggs-Gowan, Reference Greene, McCarthy, Estabrook, Wakschlag and Briggs-Gowan2020). More research would help establish the potential benefit of promoting positive parenting in breaking the intergenerational transmission of childhood adversity on child mental health.

Another important family-level mediating pathway we identified is the exposure of the children themselves to traumatic experiences. This is consistent with evidence that a family may stay locked in an environment of childhood adversity, as supported by meta-analytic evidence that children whose parents have a history of childhood maltreatment are three times more likely to be maltreated than those whose parents have no such history (Assink et al., Reference Assink, Spruit, Schuts, Lindauer, van der Put and Stams2018). Furthermore, research has also suggested that childhood adverse experiences such as maltreatment, often aggregate with low social economic status, family disruption and intimate partner violence, indicating the likely involvement of multiple complex pathways related to the family context (Appleyard et al., Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Alan Sroufe2005).

The presence of intimate partner violence further complicates the rearing environment, with its strong association with maternal mental health, household dysfunction, and parenting negative practices. Here, we found that intimate partner violence mediated the relationship between maternal childhood adversity and child emotional-behavioural problems. Intimate violence severely impacts mothers and child, through maternal exposure to violence and, simultaneously, a traumatic experience for the child (witnessing of violence). Indeed, children who witness intimate partner violence and experience harsh parenting have been found to present more severe behavioural problems (Easterbrooks, Katz, Kotake, Stelmach, & Chaudhuri, Reference Easterbrooks, Katz, Kotake, Stelmach and Chaudhuri2015). At community level, only few studies investigated the mediating effects of maternal social support and socio-economic status, with inconsistent results. This highlights the need for a more in-depth evaluation of the role of social support, especially among those mothers living in a complex intimate relationship and in socio-economically deprived environments, as they represent a particularly vulnerable population.

Importantly, our finding that some mediators were associated with each other points to the need to evaluate more multilevel-mediator models. For instance, the absence of maternal sensitive parenting could mediate the effect of intimate partner violence on child conduct problems (Zvara et al., Reference Zvara, Mills-Koonce, Carmody and Cox2017). This is in line with previous evidence that having a supportive romantic partner and low levels of intimate partner violence are a buffer against the intergenerational cycle of abuse (Jaffee et al., Reference Jaffee, Bowes, Ouellet-Morin, Fisher, Moffitt, Merrick and Arseneault2013). In addition, both maternal and paternal hostility and parenting discipline were found to be inter-correlated and both acted as significant mediators between MCA and child externalising behaviours (Rijlaarsdam et al., Reference Rijlaarsdam, Stevens, Jansen, Ringoot, Jaddoe, Hofman and Tiemeier2014). This points to the importance of parental roles beyond the maternal one for child mental health, particularly within the family rearing environment.

This review showed that more than 90% of studies identified were conducted in high-income and western countries, whereas most of the world's children and adolescents live in low- and middle-income countries. On one side, this could reflect the fact that we only included studies published in English. However, it could also point to a real need for more studies in low-income countries which face greater financial and human resources constraints in the allocation of their health and social protection resources. In addition, society's attitude and culture can influence family-level factors, another area that demands additional exploration (Dwairy et al., Reference Dwairy, Achoui, Filus, Rezvan nia, Casullo and Vohra2010). For example, an effect for maternal parenting practices has been found to be more significant in the Middle East and South Asia, where fathers are less involved in parenting because of cultural differences (Dwairy et al., Reference Dwairy, Achoui, Filus, Rezvan nia, Casullo and Vohra2010). Previous evidence has also shown that East Asian mothers may be more psychologically controlling than Western mothers (Pomerantz & Wang, Reference Pomerantz and Wang2009). A cross-national investigation in six countries indicated that a more frequent experience of physical discipline was less strongly associated with adverse child outcomes in countries where the experience of physical discipline is more normative for the cultural context (Lansford et al., Reference Lansford, Chang, Dodge, Malone, Oburu, Palmérus and Quinn2005). However, whether these cultural differences influence the relationship between MCA and children's emotional-behavioural development remains to be established.

This review has a number of strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review based on the ecological framework that synthesises the mediators and moderators in the relationship between MCA and children's emotional-behavioural development, and the first to meta-analyse its possible mediating pathways. For example, here we were able to show specificity for the mediating effects of maternal depression and negative parenting practices with a meta-analytic approach, highlighting the role of maternal mental health as a key factor. Importantly, this review points to the urgent need to investigate community and societal -level mediators and moderators, including social support, socio-economic status and cultural differences.

Some limitations should also be addressed. First, we could not include all studies in the meta-analysis due to differences in outcomes and lack of estimates for some of the mediators. Second, all studies were based on retrospective reports of maternal childhood adversity, which might introduce recall and reporting biases, although retrospective reports in adulthood of major adverse experiences in childhood have been validated and they have a worthwhile place in research (Hardt & Rutter, Reference Hardt and Rutter2004). Third, our review only focused on the traditional maternal role, while many modern families do not follow the traditional nuclear family structure. We focused on mothers as their role has been the most frequently reported in the literature and as they are still the most common carers in many societies, playing a vital role in practical interventions. However, fathers, as well as stepparents, guardians and extended family as caregivers could all play an important role in the pathways to children's outcomes and modern family structures should be more comprehensively evaluated in this context. Lastly, most studies were conducted in high-income western countries as discussed above, which might limit the generalisability of the findings to low- and middle-income countries. Nonetheless, the fact that some studies were conducted in disadvantaged groups, such as teenage mothers, low-income families and clinical settings, would help make the results more generalisable.

Conclusion

Families, schools, and communities, as well as clinicians could benefit from this evidence for conducting more effective interventions. For example, in primary health settings, physicians should be mindful of the broader implications of maternal depressive symptoms and respond with prompt assessment and further referral for symptom management, particularly in those mothers who also have a personal history of childhood adversity. In maternity and community health settings, an optimal parenting style and higher individual resilience in both mother and child can be promoted to mitigate family-level risk (Avellar & Supplee, Reference Avellar and Supplee2013). At a societal level, it would be important to increase public awareness on the importance of good mental health and positive parenting. These multilevel interventions informed by established mediators could help minimise the impact of MCA on children's mental wellbeing in the most vulnerable children and their families, helping them pursue a more positive life trajectory.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722001775

Acknowledgements

XM is supported by the King's-China Scholarship Council (K-CSC). Paola Dazzan's research is partly supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London and the UK Medical Research Council (Grant MR/S003444/1).

Author contributions

XM conceptualised the review, carried out the searches, screened the abstracts and full texts, did the narrative synthesis, extracted data for the meta-analysis, conducted the meta-analysis, drafted and finalised the manuscript. AB conceptualised the review, screened the abstracts and full texts, and revised the manuscript. CS supervised the meta-analysis, extracted data for the meta-analysis and revised the manuscript. AJL provided feedback on methodology and revised the manuscript. PJC, RP, MM (Ms Matter), NM, KH, CM, SH, AS, GS, CP, MM (Dr Mehta), GM and ARM all contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. CN and PD contributed to the conceptualisation, supervised the work and revised the multiple versions of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.