Can international courts induce greater compliance with their rulings? How should they engage noncompliant states? This paper introduces the concept of dialogic oversight, a process by which judicial or quasi-judicial bodies monitor compliance with their rulings or recommendations through multilateral exchanges of information. It typically involves a combination of mandated self-reporting, third-party involvement, and supervision hearings. This form of oversight, present in domestic and international law, opens channels of communication with state agents and civil society, creating spaces for “dialogic justice.”Footnote 1

We explore the effectiveness of this strategy by analyzing all the supervision hearings conducted by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) through 2019. State compliance is one of the central challenges faced by international courts. Although human rights rulings may have significant impacts in the absence of compliance, reparations are central to the effectiveness of human rights regimes.Footnote 2 The IACtHR has therefore emphasized the importance of state compliance, not only as a matter of justice in specific cases but also as a raison d’être for the Court.Footnote 3 The innovative monitoring system adopted by the IACtHR includes a set of practices purported to reinforce compliance, including supervision hearings.

Our study uses propensity-score matching, difference-in-differences, and doubly robust event-history estimators to assess the effect of supervision hearings on the probability of state compliance, using a database that covers all reparation measures ordered by the IACtHR between 1989 and 2019. We present three main findings. First, supervision hearings increase the likelihood of state compliance by about 3 percent on average per year, a substantial increase over the baseline. Second, effective oversight does not exclusively depend on public exposure. Private supervision hearings, which dominate the IACtHR's agenda, drive the positive results. However, third, effective dialogic oversight depends on the engagement of a vibrant civil society.

These findings underpin our contributions to the literature. We conceptualize dialogic oversight as a distinctive mechanism to promote state compliance. This concept connects seemingly unrelated literatures in constitutional law and international organizations, which describe similar logics in the domestic and international legal arenas.Footnote 4 The approach is relevant for a broad range of judicial and quasi-judicial institutions because it creates opportunities to foster agreements that move implementation forward. In addition, our study offers the first empirical evaluation of the effectiveness of the IACtHR's innovative supervision hearings. Those hearings have been taken as a reference by other bodies, including the International Court of Justice and the African Court on Human and People's Rights, for their own supervision strategies. We find that hearings are reasonably effective in promoting compliance. Although the effect is modest in absolute terms, it is strong in relative terms and statistically consistent across estimators. This empirical evidence contributes to an emerging literature on how international courts can facilitate compliance with their judgments.

Dialogic Oversight and State Compliance

Two seemingly unrelated lines of research underscore how the combination of oversight and dialogue creates conditions for state compliance. The first line, focusing on domestic courts, relies on the concept of “collaborative oversight.”Footnote 5 The second, focusing on international quasi-judicial bodies, relies on the concept of “constructive dialogue.”Footnote 6 The underlying commonalties in these two literatures inspire the encompassing concept of “dialogic oversight,” presented at the end of the section.

Oversight

Legal scholars have noticed that domestic courts are not well equipped to compel government compliance.Footnote 7 The challenge is even greater for international courts, which command states to take action without much leverage.Footnote 8 Theories of international relations explain state compliance with reference to factors such as institutional capacity, political will, democracy, and states’ calculated interests.Footnote 9 While most theoretical explanations focus on causal conditions over which courts have little control, recent studies have emphasized actionable criteria such as remedial design, unified opinions, and the clarity of the courts’ rulings.Footnote 10

Monitoring is the primary instrument courts have at their disposal to ensure compliance. (We use “oversight,” “supervision,” and “monitoring” as synonyms.) Requests for information and supervision hearings open lines of communication with the state agents in charge of implementing court rulings, and expose state agents who are reluctant to comply.Footnote 11 Some international courts delegate this task, while more proactive courts exercise supervision directly. For instance, the European Court of Human Rights delegates this function to the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, while the IACtHR oversees compliance through its supervision unit.

Judicial Dialogue

In the legal literature, “dialogue” usually refers to an interactive process by which judges reach decisions or assimilate standards. Students of constitutional and international law have shown that courts can engage in dialogue among themselves, with state actors, and with civil society.Footnote 12 International courts have responded to the growing interaction between legal systems by becoming more cooperative and engaged with domestic stakeholders.Footnote 13

The idea of judicial dialogue implies that international courts communicate with the domestic judiciaries implementing their decisions.Footnote 14 Judicial dialogue often occurs through citations, without any direct contact between judges; some scholars even suggest that judicial dialogue represents an “indirect” form of judicial review.Footnote 15 In some cases, it also takes the form of technical exchanges between international courts and domestic judges or state officials.Footnote 16 Westbrook and Slaughter assert that contemporary courts are increasingly engaged in “international judicial negotiations” with other courts across jurisdictions.Footnote 17 In the realm of human rights, courts also engage in transnational judicial dialogue, establishing communication across regional tribunals at the supranational level.Footnote 18

Collaborative Oversight

Students of constitutional law argue that domestic courts can promote compliance by encouraging stakeholder participation in the monitoring process.Footnote 19 Rodríguez-Garavito introduces two concepts: dialogic rulings and dialogic monitoring. Dialogic rulings allow courts to set clear goals while leaving operational decisions to government agencies; they open a deliberative process that encourages discussion of policy alternatives to solve structural problems. Dialogic monitoring, in turn, relies on participatory follow-up measures such as public hearings, court-appointed monitoring commissions, and progress reports.Footnote 20

Botero describes this strategy as “collaborative oversight,” a model in which “the court, elected leaders, private actors, and civil society agents converge to address issues.”Footnote 21 For Botero, the impact of court rulings is shaped by the combination of court-promoted monitoring mechanisms and dense legal constituencies, which together constitute a “collaborative oversight arena,” or “a space where civil society organizations, government control agencies, the court, and the targets of the decision participate in the oversight process over an extended period of time … It involves all actors interacting in a space that encompasses several monitoring institutions: public follow-up hearings in the court, the periodic production and processing of compliance reports, and a follow-up commission.”Footnote 22

High courts rely on collaborative oversight to implement complex rulings in the realm of economic, social, and cultural rights. India's Supreme Court started using commissions to monitor the implementation of its rulings in the late 1990s, and did so most notably in the Right to Food Case of 2001. Argentina's Supreme Court combined legal teams, public hearings, and commissions to oversee the implementation of a 2008 environmental ruling in the Riachuelo basin; and Colombia's Constitutional Court employed similar strategies to protect the right to health in Case T-760 of 2008.Footnote 23

Constructive Dialogue

The concept of constructive dialogue emerged in the context of the periodic review processes of UN human rights “treaty bodies.” Each of the nine core international human rights treaties—on racial discrimination; civil and political rights; economic, social, and cultural rights; discrimination against women; torture; rights of the child; migrant workers; enforced disappearance; and persons with disabilities—relies on a committee of experts (or treaty body) to monitor its implementation.Footnote 24 Although details vary across treaty bodies, states typically submit an initial report assessing compliance with the provisions of the treaty after ratification, followed by periodic reports at intervals of two to five years. Most importantly, government delegations travel to Geneva to discuss those reports. “This so-called ‘constructive dialogue’ provides an opportunity for mutual engagement, acknowledgment of progress made, and identification of areas for improvement.”Footnote 25

Discussions of the review process frame the committees’ oversight in dialogic terms by emphasizing their advisory role. Treaty bodies claim that constructive dialogue “offers an opportunity for States parties to receive expert advice on compliance with their international human rights commitments, which assists them in their implementation of the treaties at the national level.”Footnote 26 Similarly, Grossman notes that “the purpose of the oral dialogue is to allow States Parties direct access to the expertise of the Committee members as a resource to assist states in the compliance with their obligations. Within this paradigm of cooperation, the phrase that may best capture the nature of the exchanges is ‘constructive dialogue’.”Footnote 27

Creamer and Simmons offer systematic empirical evidence that the process of self-reporting has cumulative effects in the improvement of women's rights and physical integrity rights. These effects are primarily driven by civil society participation in shadow reporting, media attention, and legislative activity. More broadly, constructive dialogue activates four mechanisms that contribute to human rights improvements: elite socialization, learning and capacity building, domestic mobilization, and law development.Footnote 28

Dialogic Oversight

Collaborative oversight at the domestic level and constructive dialogue at the international level are manifestations of a broader practice. Dialogic oversight is the process by which judicial or quasi-judicial bodies monitor compliance with their orders or recommendations through open, multilateral exchanges of information that include two-way communications with the state (as opposed to one-way reporting), as well as information provided by third parties. Dialogic oversight typically involves a combination of mandated state reporting, third-party verification, and supervision hearings.

The literature has implicitly acknowledged the importance of dialogic oversight for international human rights bodies. For example, Sandoval, Leach, and Murray define dialogue as “the reviewing process carried out by supranational human rights mechanisms of the implementation of their decisions, which includes the utilization of tools to encourage the parties to explore ways of moving implementation forward, either between themselves or with the direct help of the monitoring body.”Footnote 29 Huneeus says that international courts “should directly involve actors from the justice system in each stage of the remedy, from the original ruling to the final supervision.”Footnote 30 Dulitzky argues that the Inter-American system has been more effective where there has been dialogue between the government, civil society, and the Inter-American organs.Footnote 31 Parra-Vera asserts that IACtHR decisions facilitate dialogue between local actors locked in inter-institutional disputes, helping them overcome obstacles to implementation and create new operational frameworks.Footnote 32

Dialogic oversight does not involve the renegotiation of court orders or recommendations at the supervision stage. In contrast to Neuman's “supervised negotiation,” dialogue in this context is limited to the interpretation of obligations and their implementation process.Footnote 33 For treaty bodies, obligations are determined by the content of the treaty. For international courts, the substantive content of the measures is determined when the court adjudicates the dispute, before the supervision stage. This means that the court plays two roles: a primary role as adjudicator at the contentious stage, and an ancillary role as a mediator at the supervision stage. As a mediator, the court engages the parties in the case to facilitate the implementation of the measures ordered by the ruling.

The literatures on collaborative oversight and constructive dialogue identify two causal mechanisms to explain the effectiveness of dialogic oversight in promoting compliance. The first one is dialogic engagement with stakeholders. Kent and Taylor define this as the process by which an organization—in this case, an international court—engages stakeholders to “make things happen.” Dialogic engagement operates primarily through ideational change; it creates a two-way, relational, give-and-take to achieve an intended goal, and it fosters understanding, goodwill, and a shared view of reality.Footnote 34 For instance, Botero notes that collaborative oversight arenas generate “the effective diffusion of policy ideas and new cognitive paradigms among governmental actors [and] help diffuse the rights-based framework among those charged with designing policy and implementation.”Footnote 35 Similarly, Creamer and Simmons hypothesize that constructive dialogue prompts elite socialization, dissemination of best practices among state actors, and the development of implementation capacity.Footnote 36

The second mechanism involves civil society mobilization, facilitated by the dialogic environment. A strong civil society produces independent information about compliance and pressures the state to honor its obligations. However, studies conceptualize the role of this variable in slightly different ways. One approach envisions civil society mobilization as a mediating variable activated by dialogic oversight. Grossman, for instance, documents that treaty bodies acknowledge the importance of publicity in their deliberations to promote civil society accountability. Creamer and Simmons underscore the role of civil society organizations throughout their work, noting that “the review process sparks shadow reporting and gains a domestic audience through the national media.”Footnote 37 Another approach envisions a strong civil society as a moderating variable that compounds the effects of dialogic engagement. Botero argues that dense legal constituencies (that is, multiple and interconnected civil society organizations) leverage monitoring mechanisms to create collaborative oversight arenas. Similarly, Friedman and Maiorano state that “rulings are only likely to be implemented by a reluctant government if the organizations and activists which sought the judgement act to ensure that what the court orders is done.”Footnote 38

The two causal mechanisms reinforce each other, as civil society mobilization encourages public officials to embrace new cognitive paradigms. Yet there are potential tensions between the two. Publicity is central to activating civil society accountability, but it is less relevant—and potentially counterproductive—for dialogic engagement among elites. Publicity makes civil society mobilization relatively easy to document, while the effects of dialogic engagement remain more elusive. Here we leverage the experience of the IACtHR to assess the effectiveness of dialogic oversight in a context in which publicity has played a limited role.

Supervision in the IACtHR

The IACtHR is the regional court created in the framework of the Organization of American States (OAS). States that ratify the American Convention on Human Rights and recognize the jurisdiction of the Court agree to comply with the Court's rulings.Footnote 39 According to the American Convention, the IACtHR has advisory and adjudicatory functions.Footnote 40 It has the authority not only to decide that a state is responsible for human rights violations but also to rule on reparations due for such violations.

The most distinctive features of the Court's judicial practice are the development of an ambitious reparation framework and its monitoring of compliance. The IACtHR has consistently mandated integral reparations beyond compensatory damages, ordering a wide range of nonmonetary remedies. It has built a unique “remedial regime” including extensive measures of restitution, rehabilitation, and satisfaction; guarantees of nonrepetition; and monetary compensation. Almost every Court decision orders the state to implement multiple reparation measures.Footnote 41

Although the American Convention does not explicitly grant the IACtHR authority to monitor compliance, the Court interprets its monitoring function as an extension of its jurisdictional function. Unlike other international courts, the IACtHR retains jurisdiction over the case until it deems that the state has complied in full.Footnote 42

The Monitoring System

The IACtHR established its authority to monitor compliance through jurisprudential developments.Footnote 43 In an early interpretation of its first decision, Velasquez Rodríguez v. Honduras (1989–90), the Court clarified that it would “supervise compliance with the award of damages, and that the case would not be deemed closed until compensation was paid in full.”Footnote 44 The rationale for this oversight relied on an expansive interpretation of Article 68.2 of the American Convention on Human Rights.Footnote 45 Following this precedent, since 1996 the Court has issued regular resolutions assessing levels of compliance in pending cases. Cases are archived only once states comply in full with all reparation measures.

The Court relies on a broad set of instruments to promote the implementation of its rulings. Traditional tools include requests for information (self-reporting), the publication of supervision resolutions, and the referral of cases to the OAS General Assembly. More recent tools include supervision hearings (the focus of this study), site visits, and requests for information from third parties.

Among traditional instruments, the reporting procedure empowers the Court to ask state officials about their efforts to implement reparations.Footnote 46 Court rulings typically order states to present an initial report within a year, and then regular updates at periods of six months to over a year.Footnote 47 The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the victims’ legal representatives can respond to the reports. Based on this information, the Court issues resolutions.Footnote 48

Supervision resolutions assess the level of compliance with reparation measures ordered by the IACtHR in a given case. They do not modify the Court's original ruling, but they may provide guidance on how to achieve compliance.Footnote 49 The first part of a resolution typically makes a detailed evaluation of the implementation process to date. In the second part, the Court characterizes the status of each reparation measure as pending, partial compliance, or full compliance. After a declaration of full compliance, supervision of the individual measure is closed.Footnote 50 Supervision resolutions are the main documentary source to track levels of compliance over time.

In extreme cases, the Court can report noncompliance to the OAS General Assembly, per Article 65 of the American Convention on Human Rights. However, this “nuclear option” has proved ineffective, and it is rarely used. The Court has referred only fifteen cases to the General Assembly, typically to expose irredeemable patterns of noncompliance rather than delays in specific cases.Footnote 51

The Court has taken steps to institutionalize its monitoring function. In 2009, an amendment to the Court's Rules of Procedure introduced an explicit protocol for monitoring compliance with judgments.Footnote 52 In 2015, the Secretariat of the Court established a unit dedicated exclusively to monitoring compliance.Footnote 53 The unit has adopted novel strategies, including on-site supervision hearings and site visits, the request for information from third-party sources, and informal meetings with state delegations. This monitoring function has evolved into a sophisticated model, arguably the most innovative among international courts. Despite its increasing formalization, it retains procedural flexibility, and the Court deploys supervision actions according to the needs in each case.Footnote 54

In recent years, the Court has expanded its repertoire. For instance, in 2015, it began conducting site visits. Court delegates visit particular communities or projects to obtain information on the implementation of reparation measures. Such visits remain infrequent (only eight took place through 2019). In 2019, the Court also started to hold informal meetings with victims or state agents.Footnote 55 In contrast to hearings, these meetings allow court officials to gather information without the presence of judges. The IACtHR has also increasingly requested information and amicus curiae from third parties at the supervision stage.

In practice, supervision hearings have become the main instrument the Court uses to promote compliance. Hearings allow the Court to confront state officials with representatives of the victims and of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Because the Court can summon parties to San José, hearings do not require state approval unless they are conducted on site.

Supervision Hearings As Dialogic Oversight

In 2007, the IACtHR began to conduct hearings on compliance.Footnote 56 In contrast to hearings taking place at the trial stage, supervision hearings do not affect the outcome of the case. Supervision starts once the Court has ruled and laid out a list of reparation measures. The reparations ordered by the Court are not subject to negotiation; the hearings simply seek to document and promote compliance with those measures.

Between 2007 and 2019, the IACtHR conducted 197 supervision hearings covering 538 reparation measures (about a third of the Court's portfolio). Hearings vary in their levels of publicity, the number of cases covered, and their location, but the modal hearing is private, covers a single case, and happens at the Court's headquarters. Private hearings are restricted to judges, victims’ representatives, the state, and the IACtHR. Public hearings are open to journalists and third parties.Footnote 57 Notably, 91 percent of all hearings through 2019 were private. Most (54 percent) addressed a single case, but the Court occasionally covered multiple cases when addressing a common pattern of violations by the state. Most hearings (71 percent) were hosted in San José, and the rest took place on site.

Hearings typically take about two hours, and follow a standard sequence. State representatives describe progress in complying with their obligations; representatives of the victims and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights present their observations; and the parties have an opportunity for rebuttal. The session concludes with a discussion in which judges—three or four are usually present—informally question the parties.Footnote 58 In 2022, the Court started appointing judge rapporteurs to preserve greater continuity in supervision.

Private supervision hearings are distinctive examples of dialogic oversight. Pérez and Sandoval note: “The hearing is organized in a roundtable, symbolizing that the role of the Court is less hierarchical and more horizontal … Judges do not use their gowns … The Court usually assumes a role that is more like that of a mediator instead of an adjudicator, supporting dialogue between parties towards achieving compliance.”Footnote 59 Judges identify obstacles to implementation and suggest options for overcoming them.Footnote 60 They also promote the establishment of timetables or follow-up mechanisms. The Court itself has depicted hearings as a space to enable dialogue and agreements between parties.Footnote 61

For instance, during a private hearing on Afro-descendant Communities Displaced from the Río Cacarica Basin (Operation Genesis) v. Colombia, the parties were asked to agree on a timetable for the execution of pending reparations. The President of the Court proposed the creation of a mechanism to monitor this timetable, including participation by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and a team from the Court's Secretariat.Footnote 62 Likewise, in the cases of Sawhoyamaxa Indigenous Community, Yakye Axa Indigenous Community, and Xákmok Kásek Indigenous Community Against Paraguay, the Court explicitly scheduled a private hearing to promote dialogue between senior state officials and victims’ legal representatives.Footnote 63 Sandoval, Leach, and Murray conclude that “hearings have been most effective where the Court has facilitated communication between the parties and allowed them to establish the way forward.”Footnote 64

Public hearings are more formal and follow an adversarial model. Pérez and Sandoval note that “the Court resumes its role as an adjudicator and drops that of mediator.”Footnote 65 Public hearings usually concern major disputes over the interpretation or implementation of reparations. For instance, the first public hearing, on Sawhoyamaxa Indigenous Community v. Paraguay in 2009, followed the deaths of several community members, including children, as a consequence of the lack of compliance.

Because private hearings dominate the IACtHR's supervision strategy, they offer an opportunity to assess the effectiveness of dialogic oversight in international law. While public hearings have greater potential for shaming recalcitrant state officials, private hearings are more conducive to dialogic engagement, the first mechanism identified in the previous section. At the same time, we should not assume that private hearings happen in a sealed bubble. Given the importance of a specialized “community of practice” for the implementation of human rights reparations, a vibrant civil society—the second mechanism identified earlier—remains crucial to prompt state officials to follow the agreements achieved during private hearings.Footnote 66

Assessing the Effectiveness of Dialogic Oversight

We have seen that the IACtHR predominantly follows a strategy of dialogic oversight during the supervision process. But is this strategy effective? External observers believe so. The OAS General Assembly concluded that “private hearings held on the monitoring of compliance with the Court's judgments have been important and constructive and have yielded positive results.”Footnote 67 Similarly, Sandoval, Leach, and Murray note that the Court's hearings have “a positive effect on implementation, helping things move forward when states appear to be dragging their feet.”Footnote 68

We analyze data on every case in which the IACtHR ruled against a state between 1989 and 2019.Footnote 69 These 257 cases include 1,878 reparation measures ordered by the IACtHR. For example, in its first ruling, Velásquez Rodríguez v. Honduras (1989), the Court ordered Honduras to pay compensation for nonpecuniary damages to the victim's wife (about USD 93,000) and his three children (about USD 280,000). We observe those orders every year between the date of the ruling and the time of compliance—or through 2019, if the measure remained under supervision at the time. This produces a data set of 11,989 reparation-years.

Our dependent variable is an indicator that takes a value of 1 on the year when the state complied in full with a reparation measure (747 events), and 0 in any previous year (11,242 observations). The date of compliance is based on the qualitative information provided by the Court's supervision resolutions. Reparation measures drop from the sample after compliance, creating the structure for an event-history analysis.

Supervision Hearings

The “treatment” variable is a dichotomous indicator capturing the timing of supervision hearings. We collected information on the 197 hearings conducted by the IACtHR between 2007 and 2019, using the Court's annual reports and supervision resolutions to document their characteristics. Supervision hearings may or may not cover all reparation measures ordered in a case. Thus the coding of our variable links the timing of the hearing with the specific measures discussed at each meeting. For instance, in Bámaca Velásquez v. Guatemala (2000) the Court ordered seven reparation measures, but the hearing of May 2014 focused exclusively on the order to investigate the victim's disappearance, so we code the Court's intervention in 2014 as “treating” a single measure in this case.

Our variable hearing takes a value of 1 if a given reparation measure is monitored in any given year, and 0 otherwise. The hearings covered 768 reparation measures (or more precisely, reparation-years), but 89 percent of them (684 reparation-years) were discussed in private hearings. To isolate the effects of dialogic engagement, we also estimate duration models with an alternative measure that exclusively captures private hearings.

Confounders

We control for three factors that might affect the state's propensity to comply with a measure, as well as the Court's decision to oversee it: civil society, prior compliance, and the type of reparation. An active civil society pressures state officials to honor its obligations, but also warns the Court about state inaction, prompting oversight.Footnote 70 We measure the presence of a strong civil society using the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) index of Freedom of Association. This composite index, ranging from 0 to 1, captures the extent to which civil society organizations are able to form and operate freely, and opposition parties are allowed to form and to participate in elections.Footnote 71 We recode this variable as a dichotomous indicator of a strong civil society when the V-Dem index is greater than 0.85. This is not an extreme value in our sample, because most of the countries are democracies (the mean for the sample is 0.81, and the median is 0.84). For robustness, we also show results with the continuous measure in Table 4 (presented later).

As noted earlier, the strength of civil society is also a potential moderator of the effect of supervision hearings: dialogic oversight requires the collaboration of civil society. The use of a dichotomous indicator facilitates the interpretation of interaction terms (presented later, in Table 4). In addition, because V-Dem does not provide information for Suriname or Trinidad and Tobago, we employed additional information to complete the coding of the indicator for those cases.Footnote 72

Our second control variable captures any recent change in compliance with respect to reparation measures ordered in the same case. This dichotomous indicator takes a value of 1 if the state has complied partially or in full with any measure ordered in the case over the past two years. Progress in implementation signals that the state has mustered the political will to comply, and thus recent changes may signal further compliance with other measures in the near future.Footnote 73 At the same time, new developments on the ground prompt the Court to conduct hearings to document the status of the case. At those hearings, pending measures in the case are also reviewed and thus exposed to dialogic oversight.

Third, we note that the Court makes special efforts to monitor complex reparations, but the literature has established that governments fulfill monetary and symbolic obligations more frequently than complex reparation measures.Footnote 74 We classify the type of reparation using six categories adopted by the IACtHR in its rulings: restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction, guarantees of no repetition, obligation to investigate and prosecute perpetrators, and indemnifications (including in this group the refund of legal costs and contributions to the Court's fund for victims). The reference category in all models is restitution.

Selection Concerns and Estimation

Any assessment of oversight hearings must account for the fact that the Court selects the cases to be monitored. A naive comparison of rates of compliance for reparations with and without hearings would be misleading because the Court is not likely to hold hearings for just any reparations. Threats to inference run in two opposite directions. A naive comparison would overestimate the effect of hearings if strategic judges, concerned about the legitimacy of the Court, target promising cases in which they anticipate compliance in the near future.Footnote 75 Conversely, a naive comparison would underestimate the effect of hearings if judges focus their limited resources on difficult cases and recalcitrant states that require tighter oversight.

How does the IACtHR decide which cases need a supervision hearing? To what extent are those cases different from the cases that are not monitored? We outline answers to those questions based on the work of Pérez and Sandoval and our own interviews with members of the Court's Supervision Unit (6 July 2023).Footnote 76 At the present, there are no strict regulations of the criteria for a supervision hearing. Pérez and Sandoval note that this flexibility “is an asset for compliance” but also “generates uncertainty for stakeholders.”Footnote 77 The Court can convene a hearing following a request from parties in the case (just 12 percent of the hearings in our sample) or on its own initiative (about 54 percent of the hearings; we were unable to document the origin for the other 34 percent).Footnote 78 Parties can request a hearing at any point, but there are no formal rules for the granting of those requests or the timeline of any hearings. The Court, in turn, initiates hearings motivated by a range of circumstances: when the state self-reports progress and the Court needs to verify compliance; when there is a controversy between the parties in relation to the implementation of a measure; when the delay in implementing measures poses a risk to the physical or psychological integrity of the victims; when the Court has ordered provisional measures at the supervision stage; or when the state has failed to report periodically on implementation.Footnote 79

In most such situations, the Court is likely to focus on difficult cases and more recalcitrant states. An analysis of the reparation measures covered by the hearings reinforces this conjecture. Reparations typically deemed hard to implement (measures on rehabilitation, nonrepetition, and the prosecution of perpetrators) represent most of the orders covered by hearings (51 percent), but a small proportion of those not covered by hearings (27 percent). In contrast, easier measures of satisfaction, restitution, and monetary compensation are underrepresented in the agenda for hearings (49 percent) vis-à-vis the other cases (73 percent). This pattern indicates that a naive comparison of compliance rates is likely to underestimate the effects of dialogic oversight.

To minimize the impact of selection effects on our empirical analysis, we employ three related strategies: propensity-score matching, difference-in-differences (DiD) estimation, and doubly robust event-history models. None of these is failproof, but taken together they strengthen our confidence in the results. First, we compare the 768 reparation-years that experienced hearings (the “treated” group) to a selected group of reparation-years that are very similar in most observed respects (the “control” group). This strategy relies on the assumption that, if the two groups are balanced with respect to observed covariates, they are probably balanced with respect to unobserved confounders as well. Second, we account for any unobserved confounders driving differences between treated and untreated reparations by using a DiD estimator. This strategy relies on the assumption that the effect of those unobserved confounders remains constant over time (the parallel-trends assumption). We augment this analysis with propensity-score weights derived from the matching procedure. Third, we estimate discrete-time event-history models with covariate adjustments. Event-history models enable a more intuitive presentation of the moderating effects of civil society, but they are more sensitive to omitted confounders than DiD models. We partially address this weakness by using inverse probability matching, creating a doubly robust estimator. All the estimators presented here generate consistent results.

Propensity-Score Matching

Our matching procedure is implemented in three steps: exact matching, propensity-score estimation, and inverse probability weighting. Because conditions change over time, we identify a five-year window around every hearing (including the year of the hearing, the two years prior, and the two years after). Within this window, we select all observations corresponding to the same state and the same type of reparation measure. For instance, since a hearing on the Furlán case covered a measure of nonrepetition against Argentina in 2015, our matched sample will include all measures of nonrepetition for Argentina in 2013 through 2017. This procedure identifies observations plausibly subject to hearings, but it reduces our sample size by 28 percent (from 11,989 to 8,581). Using this restricted sample, we estimate the probability of a hearing with a saturated logit model that includes all observed covariates (civil society, change in compliance, type of reparation, and a continuous variable for the number of years since the Court's decision), plus interactions among those variables. Finally, we use the predicted probability resulting from this model to construct an inverse probability weight (IPW) for all observations in the restricted sample.Footnote 80

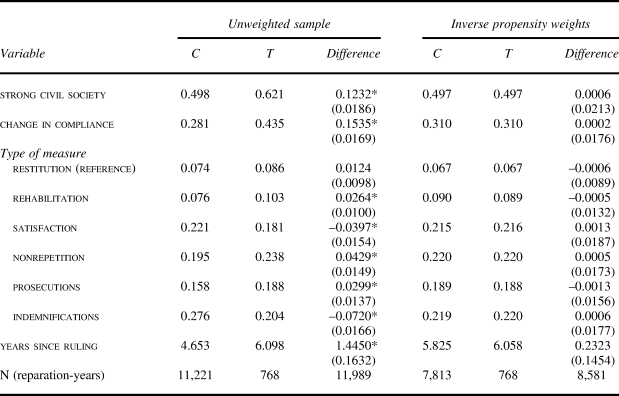

Table 1 presents balance tests for all covariates in the original sample (N = 11,989) and in the IPW-matched sample (N = 8,581). Data for the original sample suggest that hearings are more likely under a strong civil society, following recent changes in compliance, in cases with “difficult” measures (rehabilitation, nonrepetition, or prosecution of perpetrators), and in cases with a longer history of noncompliance. These differences, however, disappear in the matched sample. Thus, while there is no significant difference between the rate of compliance for treated and untreated observations in the unmatched sample (the average rate is about 6 percent per year in both groups), the balanced sample shows a significant difference between the two groups, with rates of compliance close to 5 percent in the treated group and 2 percent in the untreated group (p < .05).

Table 1. Balance tests for matched sample (inverse probability weight)

Note: Entries are means for Control (C) and Treatment (T) groups, plus difference in means (with standard errors). *p < .05.

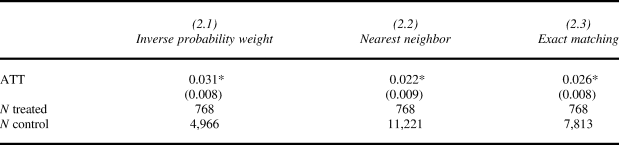

Table 2 compares estimates for the ATT (the average treatment effect among the treated—that is, the reparations subject to hearings) obtained under this procedure against two alternative matching procedures. Model 1.2 reports the estimate under the IPW procedure described earlier. Model 2.2 selects at least two control observations for every treated observation using nearest-neighbor matching with replacement. This procedure (Mahalanobis distance) relies on the same set of variables as model 2.1 (window variable, civil society, change in compliance, reparation type, and age of the decision). In turn, model 2.3 selects at least two control observations for every treated one using exact matching. This procedure relies on the same set of variables except age of the decision, because it was not possible to find exact matches for all hearings when using this continuous variable. We find, with results consistent across all alternative matching strategies, that hearings increase the probability of compliance by between 2 and 3 percent per year.Footnote 81

Table 2. Alternative matching strategies

Note: ATT (average treatment effect among the treated) is defined as E(y 1 − y 0 | treatment = 1). *p < .05.

Difference-in-Differences

While the matching procedure is able to balance observed covariates, it assumes that unobserved covariates are equally balanced. To minimize the impact of unobserved covariates in our estimation, we further model the effect of hearings using a DiD design. This approach relies on the idea that reparations subject to hearings could be intrinsically different from the rest in ways that affect compliance. We distinguish those reparations using group fixed effects, which identify reparations exposed to treatment even before they experience a hearing. Similarly, it is possible that the Court adopted hearing procedures after 2006 because rates of compliance were already in decline. We account for those unobserved historical conditions using period fixed effects. The resulting DiD equation is

where Yit is a dichotomous indicator of compliance for the i-th reparation measure in year t, Hit is a treatment indicator that captures exposure to a hearing for any given reparation-year, Gi is a group variable that distinguishes reparations selected for treatment, Pt is a period variable that distinguishes time effects, Xit represents a potential set of covariates, α is the baseline rate of compliance for untreated reparation measures in the period preceding the implementation of hearings, and εit is a residual. Under this design, we interpret δ as the ATT. Because our dependent variable is dichotomous, this estimate corresponds to a linear probability model.

We define group and period variables in two ways for greater robustness. In the first set of models presented in Table 3, the group variable is a single dummy that distinguishes reparations selected for hearings from those that never experienced a hearing, and the period variable is a single dummy that distinguishes the eras before (1989–2006) and after (2007–2019) the adoption of supervision hearings by the IACtHR. This design mimics the conventional, two-time-period DiD (with standard errors clustered by reparation). In the second set of models, the group variables identify individual reparations (1,878 groups), and the period variables identify particular years (1989, 2019). This design mimics a two-way fixed-effects (TWFE) model. Such models have two known problems, but they represent lesser concerns for this study.Footnote 82 One is that the TWFE estimator compares not only treated versus nontreated but also newly treated versus already-treated observations. We do not have “already treated” observations in our study because our treatment variable captures hearings on the year when they take place; reparations do not remain “treated” in later years. Preliminary analyses showed that the effect of hearings declines quickly after the meeting, so we assume that units switch in and out of treatment within a year. The other concern with TWFE is that the ATT may vary for different cohorts. This is plausible, but the limited number of hearings per year, and the fact that we cannot assume reparations remain treated after a hearing, prevents the use of estimators for heterogeneous effects.Footnote 83 We thus estimate homogeneous treatment effects.

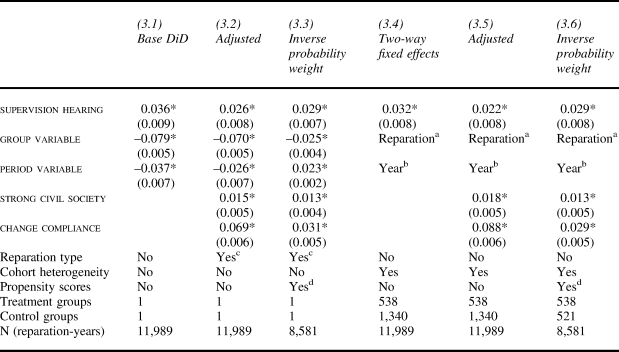

Table 3. Effect of supervision hearings on compliance (difference-in-differences)

Notes: Estimates reflect ATT (average treatment effect among the treated) in linear probability model (standard errors clustered by reparation). *p < .05.

a Models 2.4–2.6 are adjusted for group effects (1,878 reparations). Estimates not shown.

b Models 2.4–2.6 are adjusted for year effects (1989, 2019). Estimates not shown.

c Models 2.2 and 2.3 include dummy variables for five reparation types (rehabilitation, satisfaction, nonrepetition, prosecutions, and indemnifications; restitution is reference category). Estimates not shown to save space. Reparation types are absorbed by fixed effects in models 2.5–2.6.

d Matching procedure reduces sample size in models 2.3 and 2.6.

Table 3 presents the results of six DiD models. As we explained, models 3.1 to 3.3 assume just two groups and two periods, while models 3.4 to 3.6 assume 1,878 groups and thirty-one time periods. The first model in each set uses a basic DiD specification without any additional adjustments. To relax the parallel-trends assumption, models 3.2 and 3.5 augment this specification by adding controls for a strong civil society and recent changes in compliance for the case. (Model 3.2 also controls for the type of reparation, a feature absorbed by reparation fixed effects in model 3.5.) Finally, models 3.3 and 3.6 estimate the adjusted regression using the matched sample with inverse propensity weights.

The estimates in Table 3 indicate that hearings have an ATT of about 3 percent per year. Estimates for the full sample range between 0.022 and 0.036, while estimates for the weighted sample are 0.029 in both instances. While 3 percent may seem small, note that the expected rate of compliance for untreated units in model 3.3 is about 2.4 percent, while for treated units it is about 5.3 percent; thus, supervision hearings may double the probability of compliance. Dialogic oversight does not guarantee state compliance, but it improves the conditions for the adoption of reparations. In the following section we explore how civil society boosts these effects.

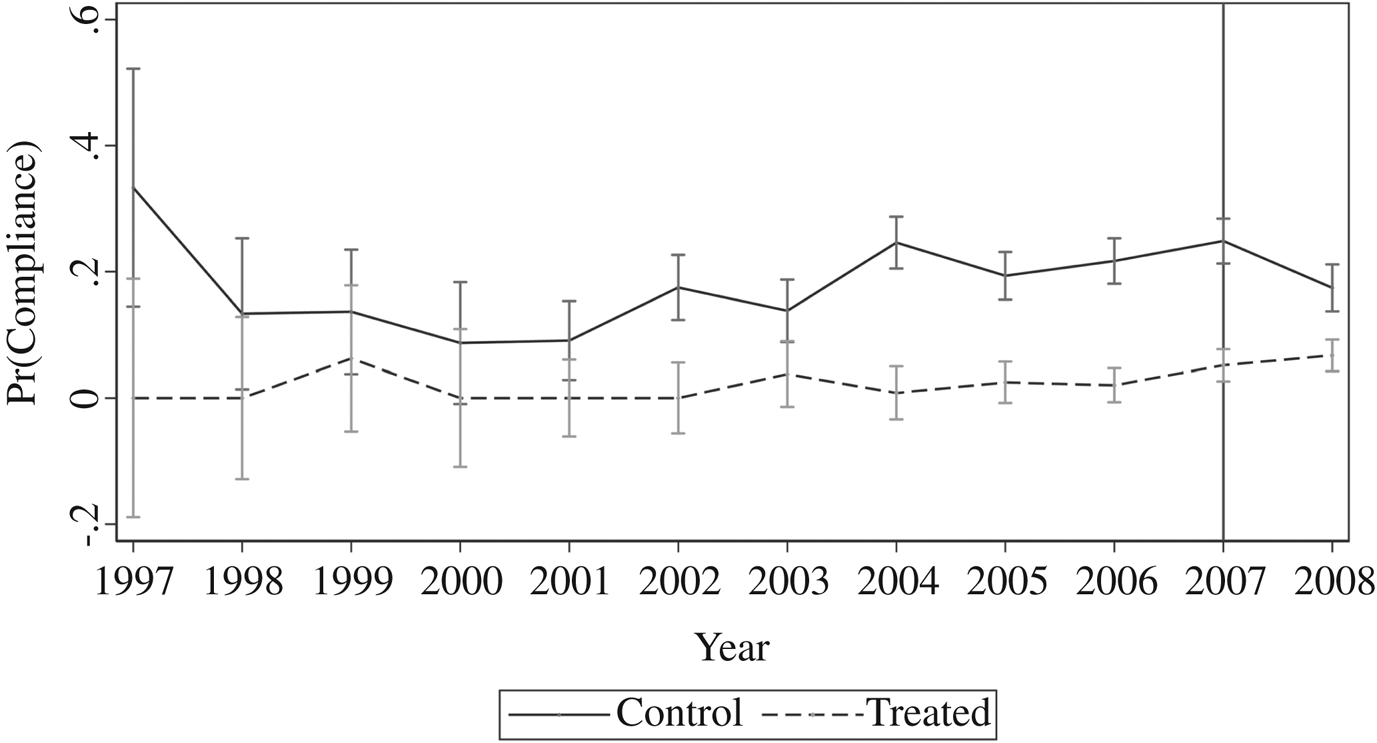

We probe the parallel-trends assumption underpinning Table 3 by tracing variation in compliance within the treatment and control groups prior to 2007, the year when the IACtHR started conducting supervision hearings. Figure 1 compares the rate of compliance for the treatment group (the set of reparation measures that eventually were subject to supervision hearings after 2007) and the control group (the set that never experienced a supervision hearing) between 1997 and 2007. Treated reparations historically saw less compliance, indicating that the IACtHR decided to monitor “hard” reparations with a lower probability of success. The difference between the two groups becomes statistically significant after 2004, partly as a result of the larger number of observations, as the Court decided more cases. However, there is no indication of diverging trends prior to 2007, and certainly no indication of an increase in compliance among the group of reparations later subject to supervision hearings.

Figure 1. Trends for compliance for treatment and control groups were parallel before 2007

Event-History Models

Our third estimation strategy relies on a discrete-time event-history model. This strategy allows us to estimate the probability of compliance for any given observation, with the inverse of this probability representing the expected time to compliance (in years). Because they do not rely on a linear probability assumption, event-history models presumably estimate predicted probabilities more accurately than the DiD models presented before. Our estimator of choice employs a complementary log-log link because compliance is a rare event, and accounts for duration dependence using a sextic transformation of time, measured in years since the date of ruling.Footnote 84

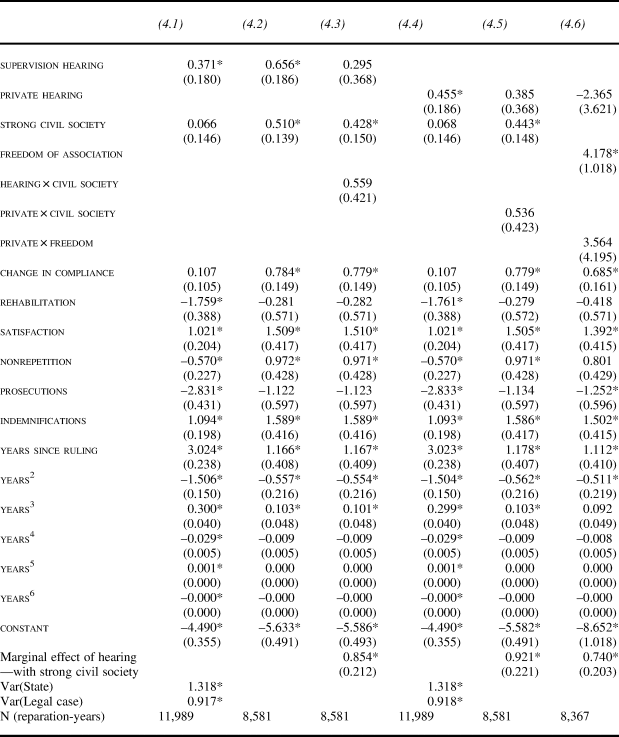

Table 4 presents six event-history models. We take advantage of this approach to probe the two causal mechanisms discussed earlier. To probe the role of dialogic engagement, we compare treatment estimates for our standard measure of hearings (4.1–4.3) to a different set of models, including a more restrictive measure that captures exclusively private hearings (4.4–4.6). If supervision hearings operate through dialogic engagement, the modal (private) hearing should not be less effective than the average hearing. To probe on the role of civil society, we estimate three models (4.3, 4.5, and 4.6) that include an interaction between hearings and a strong civil society. In those models, the coefficient for hearings reflects the effect of supervision under a weaker civil society. The marginal effects of hearings under a strong civil society are reported at the bottom of the table.

Table 4. Effect of supervision hearings on compliance (event-history)

Notes: Entries are complementary log-log estimates (standard errors clustered by reparation). Models 4.1A and 4.3A assume frailties by state and legal case. Matching reduces N in models 4.2, 4.3, and 4.6. The marginal effect in model 4.6 is calculated for the 75th percentile of Freedom of Association. *p < .05.

All these models control for the presence of a strong civil society, recent changes in compliance, and type of reparation. In addition, we try alternative estimators to check the robustness of our results: models 4.1 and 4.4 estimate the average effect of hearings and private hearings using the full sample and an event-history estimator that includes frailties by state and legal case. The remaining models, in contrast, employ a doubly robust estimator that weights observations using our IPW. Models 4.1–4.5 include our dichotomous measure of a strong civil society, but model 4.6 employs the original Freedom of Association index created by the V-Dem project.

We see three main findings in this table. First, supervision hearings improve the conditions for compliance. The magnitude of the effect is notably similar to the one estimated by DiD models: hearings increase the average probability of compliance by 3 percent (from 0.108 to 0.138) in model 4.1 and by 2 percent (from 0.024 to 0.046) in model 4.2.Footnote 85 For model 4.1, this small difference translates into a reduction of the expected time to compliance from nine years to seven years.

Second, it is clear that the beneficial effect of hearings is not driven by the visibility achieved by a few public hearings. In line with our thesis about dialogic engagement, private hearings are also effective: in model 4.4 (akin to model 4.1), private hearings increase the average probability of compliance by almost 4 percent (from 0.108 to 0.145), which maps into a similar reduction of the expected time to compliance, from nine to seven years.

Third, dialogic oversight most likely depends on the collaboration of civil society. Models 4.3 and 4.5 show that hearings have little effect on compliance when civil society is weak. In contrast, their impact is sustained by a strong civil society. In model 4.3, the marginal effect of hearings under a strong civil society (0.854, p < .001) translates into an expected increase in the probability of compliance of almost 4 percent (0.030 to 0.067). Similarly, in model 3.5, the marginal effect of private hearings with a strong civil society (0.921, p < .001) translates into an increase in the probability of compliance of just over 4 percent (0.030 to 0.071), with a concomitant reduction in the expected time to compliance from thirty-four to fourteen years. This finding remains unaltered when we replace the civil society dummy with the continuous V-Dem index (model 4.6).

Conclusion

Dialogic oversight, as practiced during the supervision hearings conducted by the IACtHR, can promote better compliance. It does not guarantee compliance, but under the right circumstances it does create conditions for state action. The experience of the IACtHR is consistent with the experience of UN treaty bodies, where Creamer and Simmons note that “the evidence supporting the contribution of constructive dialogue to rights improvements is reasonably strong.”Footnote 86

This article makes two important contributions. First, we extend the idea of dialogic monitoring into the international arena, connecting seemingly unrelated literatures on domestic courts and international treaty bodies.Footnote 87 The concept of dialogic oversight emphasizes the ability of monitoring bodies to leverage a combination of state self-reporting, stakeholder engagement, and multilateral dialogue during supervision hearings.

Second, we offer the first empirical assessment of the effectiveness of oversight hearings in the IACtHR. Our estimating strategies take seriously the inferential threats created by the fact that the Court selects which cases (and specific orders) should be subject to supervision hearings. Our best estimate is that hearings produce a short-term increase of about 3 percent in the annual probability of compliance. Although this effect may look small, it represents a relative increase of between 36 percent and 120 percent from the baseline expectation of compliance (depending on the sample and estimators used). This can translate into substantial reductions in the expected time to compliance. This finding complements recent empirical studies showing that the IACtHR can promote compliance at the adjudication stage by ruling unanimously and clearly.Footnote 88

These conclusions reinforce findings on the relevance of dialogic engagement to compliance in other fora. In international investment arbitration, parties have expanded the use of post-award settlements, which promote constructive dialogue between the investor and the host state.Footnote 89 In the United States, federal agencies’ failure to comply often leads to a delicate dialogue between the agency, judge, and plaintiff. This process entails the judge's access to information on the agency's difficulties and efforts to comply, and a complex negotiation over the terms and timing of compliance.Footnote 90

Strategies of dialogic oversight may not be effective in all contexts, and further analysis of oversight mechanisms will be necessary to guide supervision strategies. Our analysis suggests that a strong civil society is necessary for this strategy to work. Systematic studies of compliance will help establish best practices and models of supervision for international courts operating in different environments. Additional research must determine the specific mechanisms through which civil society makes dialogic engagement most effective, and how courts can leverage those mechanisms to strengthen the international justice system.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LEQJEQ>.

Acknowledgments

This paper was developed at the University of Notre Dame's Reparations Design and Compliance Lab. We are indebted to the Kellogg Institute for International Studies for supporting the Lab. Ana Lucía Aguirre, Diane Desierto, Gary Goertz, Alexandra Huneeus, Mariela Morales Antoniazzi, Paloma Núñez, Gabriela Pacheco, Emilia Powell, Julio Ríos Figueroa, Pablo Saavedra, Clara Sandoval, and our colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Public and International Law, the University of Minnesota, Florida International University, Texas Tech University, and IE University in Madrid offered valuable feedback.