INTRODUCTION

This paper reports on a project conducted with representatives of indigenous Māori organizations (businesses/trusts/incorporations) that are active in New Zealand land-based sectors. The broad aim of the research was to assist these organizations in thinking about their current and future positioning with regard to climate change. Since indigenous groups are very much at the interface of community, economic, social and environment issues (see, e.g., Stevens, 1997; Berkes, Reference Berkes2009; Raymond et al., 2010), climate change is an issue of some significance.

Initially the intent of the project was to explore the risks of climate change to Māori. Since around 50% of its current asset base is in primary industry such as agriculture and forestry, for the Māori people, or tangata whenua (‘people of the land’), it seems manifestly clear that seeking to understand and mitigate the potential excesses of climate change is an important matter. However the project quickly took on a more ambitious agenda. With a rapidly growing asset base in land-based sectors, and with distinctive values related to land, resource use and enterprise, the notion that Maori might respond positively to and even benefit from climate change became the primary focus.

With this early reframing of the project it became immediately clear that extracting competitive advantage out of climate change is a highly complex and ‘messy’ issue whose realization would require a careful intertwining of strategic decision-making with traditional cultural values, community, sustainability and natural resource management. Given this level of complexity it was decided from the outset that there was a need for methodological framework that could not only outline a process for exploring these kinds of ‘messy’ or ‘wicked’ problem situations, but also one that does not shy from recognizing diverse subjectivities and making explicit how they reflect and/or underpin strategic action. In alluding to the interconnections between those who live on earth and climactic elements, Māori legends often interpret significant climactic events as arising out of interactions between traditional mythical Gods and natural elements such as the ocean, wind and forests; and contemporary research on these topics (see, e.g., Ulrich, Reference Ulrich1993; Tunks, Reference Tunks1997; King, Penny, & Severne, Reference King, Penny and Severne2010), strongly emphasizes the value of taking these traditional interpretations and ways of knowing into account in strategic decision-making. However, although there are these broadly shared understandings about the interconnection between natural elements and human behaviour, it would be wrong to suggest that there is such a thing as a single ‘Māori worldview’ (‘Te Ao Māori’) that pertains to climate change, hence the need for a methodology can accommodate such a position. More will be said about this shortly.

In what follows the paper begins by outlining the broad methodological framework used in the study and then the study design. It then provides some background information on the project. The main substantive part of the paper has two parts: the first, a section that seeks to capture some of the ‘appreciations’ that, for Māori, might enable and/or constrain strategic activity in the climate change arena; the second, a discussion on how various modelling tools associated with the primary methodology were used in the project.

Box 1 Brief historical background on New Zealand’s Māori and Pakeha (European) Communities

Most historical commentators believe that Māori reached New Zealand in about A.D. 800. In 1840, Māori chiefs and the British government signed the Treaty of Waitangi. This involved Māori ceding sovereignty to the British while retaining territorial rights. The first organized colonial settlement to New Zealand began that year. A series of land wars between 1843 and 1872 ended with the defeat of Māori. The British colony of New Zealand became an independent dominion in 1907. In recent years, successive governments of New Zealand have sought to address longstanding Māori grievances through financial and land ownership settlements. Currently Māori account for ~15% of the 4.5 million population. Tribal-based Māori businesses, many of which have been set up as a result of Treaty of Waitangi settlements, are currently valued at $50 billion. In addition to the land and sea-based sector – forestry, dairy, red meat, seafood – these now include major investments in geothermal, digital, services, education, tourism and housing.

SOFT SYSTEMS METHODOLOGY

In simple terms, Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) seeks to assist problem owners and/or decision makers to better understand and agree on action in complex and/or multi-perspective situations. Unlike traditional rational problem solving methodologies that focus on working out how to do a defined what, in SSM ‘ … ends, goals, purposes are themselves problematic …’ (Checkland, Reference Checkland1981: 316). Hence both the what and the how are at issue. Aligned with this is distinctive image of research. This is less about ‘expert’ knowledge being deployed to deal with a defined problem, and more about a process occurring in which interested parties first develop an adequate formulation of the problem situation before attempting to take action to ‘improve’, but not necessarily ‘solve’ it.

SSM has developed considerably since Peter Checkland’s first major formulation of it in 1981, and there is now an extensive literature that describes various approaches to it, and which reports on its application across various settings. Although it has been subject to a number of revisions and modifications during the period between its two major formulations (1981 and 1990), the original ‘seven stage’ SSM continues to be the most widely known. As such this will be the main point of reference here.

Of the seven stages, 1 and 2 aim to develop an initial and holistic understanding of the various issues that might pertain to a problem situation, as well as the range of interpretations/subjectivities that might underpin these. Often these are represented in the form of one or more drawings or ‘rich pictures’. As the study or intervention proceeds, these understandings, typically focusing on key roles, values and norms expressed by, and/or associated with the various participants, are further elaborated upon and refined, as are any other aspects that pertain to the situation. Once an initial appreciation of a problem situation has been arrived at, Stages 3 and 4 involve narrowing down to focus on specific areas that seem to offer the prospect of generating useful learning and insight. Stage 3 does this by developing a precise textual description of what are referred to as ‘holons’ or ‘systems’ (‘systems’ hereafter) each of which embodies a particular subjective perspective, ‘viewpoint’, or ‘weltanschuaang’. In Stage 4 these textual descriptions are expanded upon and captured in the form of conceptual models. These delineate a sequence of linked activities expressed using verbs, that logic dictates need to occur in order for the system to do what is being claimed it does. More will be said about this later; however at this stage, it is important to note that these textual and conceptual devices are generally not required to represent anything tangible in the so-called ‘real world’. This is one of the key defining features of SSM: the models must be relevant to the real world but primarily they are abstractions that are designed to assist interested parties in thinking about possible real world action to improve a given scenario. As, Williams nicely puts it, ‘One of the interesting things about SSM, is that it constrains your thinking in order for you to expand your thinking’ (Reference Williams2005: 2).

Once these abstract devices have been designed, and deemed to be ‘fit for purpose’ as a way of structuring debate and generating learning, SSM’s Stage 5 uses them to identify nominally ‘desirable’ actions, which then, in Stage 6, are considered from a feasibility perspective. Scholars and practitioners of SSM often regard this moving back and forth between the abstract and perceptions of ‘the real’ in order to generate insight and take action, as the real ‘powerhouse’ of the methodology (Checkland & Scholes, Reference Checkland and Howell1990; Davies & Ledington, Reference Davies and Ledington1991; Williams, Reference Williams2005).

Having considered the feasibility of actions that are otherwise deemed to be desirable, Stage 7 is where action of some sort occurs. This is not always a substantive intervention. It could, for example, simply involve further debate, or a more detailed investigation of the situation, or evaluation of options that have been earmarked for improving it. As we shall see, this is what eventuated in this project.

At this point, it is important to reinforce the point that although these stages are conceptually distinct and have been described sequentially, their application is often simultaneous and the whole process iterative. Indeed it would be very unusual to not have a deliberate to-ing and fro-ing between the various stages. Moreover the methodology itself is designed to be used flexibly. This acknowledges not only the reality the terrain covered by projects of this ‘messy’ nature can evolve and sometimes change dramatically, but also the reality that resource constraints and the priorities of participants often dictates what can be accomplished within a given context and timeframe.

THE CLIMATE CHANGE RESEARCH PROJECT

Traditional Māori values pertaining to business

Since the primary topic under discussion here is potential commercial advantage in relation to climate change, it is worth beginning by making a few comments about traditional Māori values towards business in general. While these are not necessarily considered to be inimical to Western values, they do tend to differ in key areas. Prominent amongst these are the priorities accorded to environmental protection, community involvement and obligations, and the typically much longer planning horizon. The latter is worth emphasizing. Geared towards creating intergenerational wealth, planning horizons can extend well into the long term (see, e.g., Karaitiana, Reference Karaitiana2010). This orientation towards caring for nature, people and enterprise, all for the enhancement of future generations is strongly linked to values associated with whakapapa (geneology) and kaitiakitanga (stewardship). Beyond that, for Māori, economic activity has historically been structured more around community needs than around wants or desires. Hence in the Māori enterprises literature, collectivism and community responsibility, rather than individualism and competition, are strongly emphasized (Klein, Reference Klein2000; Mataira, Reference Mataira2000; Durie, Reference Durie2003; Love & Love, Reference Love and Love2005; Petrie, Reference Petrie2006).

Background to the project

At the outset of this project it was very clear that conducting research in an indigenous setting would likely present a set of challenges that would require careful foresight as well as a good deal of preparatory work. To some extent this is necessary in all action research-type projects; however the range of issues to be considered are of a different order and significantly more pressing when nonindigenous researchers or change agents work in indigenous settings. In particular, the requirement for cultural awareness and sensitivity shifts from what might otherwise be seen to be a desirable but perhaps not essential ‘add on’, to being a core requirement, and one that has to be seriously grappled with. This is an even more pressing concern in the relatively common scenario in which indigenous peoples experience tension with, if not outright alienation from, what is perceived to be a dominating culture.

Against this background, the most pressing issue to be grappled with was the stark requirement of ‘Kaupapa Māori’ research that the researchers must not only be Māori, but also conversant in all things Māori (Glover, Reference Glover2002; Jahnke & Taiapa, Reference Jahnke and Taiapa2003; Walker, Eketone, & Gibbs, Reference Walker, Eketone and Gibbs2006). In this case that was clearly impossible. Despite this, there were things that could be done to increase the chances that the research would firstly take place at all, and then hopefully to meet some key objectives. In some manner or other the actions that were taken reflected the acceptance that legitimate questions could be raised about the motivations behind the study, and about the alignment of the two party’s values. From a philosophical point of view, questions could be asked about possible tensions between what some might characterize as key differences between indigenous and nonindigenous ways of constructing, knowing about, explaining situations, as well as about interacting in them. There is also the general understanding that where indigenous research is undertaken it should be done ‘with’ the stakeholders concerned and certainly not ‘on’ them.

Since how all of this potentially difficult territory was traversed is discussed in some detail in another paper (see Brocklesby & Beall, 2017), it is not rehearsed here. What can be said though is that for the first author in particular (a US citizen), it involved a good deal of preparatory work; most notably becoming more familiar with and incorporating where possible aspects of Māori language and tikanga (customs); (re)-studying the Treaty of Waitangi and history of interaction between the Crown and Māori; and a good deal of brushing up on cross-cultural research methods. In addition it involved applying as expeditiously as possible key principles articulated tino rangatirtanga (where meetings with Māori authorities took place to determine what research would best contribute to Māori development and self-determination, see Walker, Eketone, & Gibbs, Reference Walker, Eketone and Gibbs2006); whakawhangaungatanga (establishing relationships of trust) aspects of which involved general discussion of whakapapa/genealogy before launching into the climate change specific research questions; and importantly recognizing that all knowledge shared must be treated with utmost respect and protected.

It is also worth noting that the research design broadly followed the tiaki model, where Māori authorities largely facilitate and mentor the research process (O’Sullivan & Dana, Reference Osterwalder and Pigneur2008). Initially key to this was to elicit the help of Māori advisors in facilitating the inclusion of a broad range of iwi, covering different regions and across different sectors to provide for some degree of diversity. The outcome of this was that 15 Māori businesses/trusts/incorporations, all active in land-based sectors were identified as possible participants in the project. Ten of these agreed to participate and were included in the study. For each entity, a representative with responsibilities for strategic decision-making was identified as the key participant. Table 1 provides information on the sample included in this research. However, iwi (tribal) affiliation and any identifying features of the organization have been deliberately excluded.

Table 1 The project participants

The principal method of inquiry for this research was through in-depth interviews and follow-up face-to-face and/or telephone/email discussion. The interviews followed a semi-structured format in order to provide flexibility for the unique knowledge and background of each participant. With these it was considered to be very important to not condense the responses and lose the unique voice of each participant. Knowledge according to Māori is acquired through taking an holistic approach, and ‘there is no single or privileged truth according to Māori-centred knowing and being’ (Takino, Reference Takino1998: 291). While they share similar values, historical experiences and localized interactions have created a diversity of perspectives throughout Māoridom. Hence in the following section, a concerted effort has been made to privilege the voice of each participant through the use of full quotes. While it is up to readers to form their own judgments, we have been conscious of and sought to avoid ‘othering’ research practices where the nonindigenous researcher imposes analysis on indigenous people (Smith, Reference Smith2005).

This research occurred in two broad phases. Phase 1 – broadly corresponding with what in later formulations of SSM is referred to ‘social and political system analysis’ involved exploring participants perceptions of relevant roles, values and norms in relation to climate change. This phase concluded with participants being asked to identify priority areas for strategic action. In Phase 2 these ‘transformation priorities’ informed the construction of a number of conceptual models the purpose being to further structure a debate about what actions Māori organizations might take in furthering their climate change-related interests.

Phase 1: ‘social and political analysis’ – investigating values, roles and norms

As Māori protocol dictates, the opening of each interview sought to cover key aspects of both interviewer and interviewee’s background, or whakapapa. Thereafter a number of trigger questions, all revolving around values, roles and norms, were used to: (i) elucidate perceptions of climate change and the potential role for Māori; (ii) consider the organization’s strategy and goals, and areas of potential or perceived comparative advantage; (iii) to identify possible transformations and/or leverage points that might generate comparative advantage in this context.

On values

This section reports on participants’ beliefs about what are humanly ‘good’ or ‘bad’ principles of behaviour, some in general, but others relating to the situation under investigation (Checkland & Scholes, Reference Checkland and Howell1990: 49). Within the SSM framework, values are a core component of understanding any problem situation. However they are even more central to understanding Māori, it being strongly emphasized by almost all participants that it is values that underpin Māori identity and set Māori apart from Pākehā, or non-Māori.

One of our key points of difference is our authenticity. Our ability to remain true to ourselves and to our culture and to our values, and also the fact that we do things differently. And not only authenticity but longevity, cause we’re not going anywhere.

It is worth noting that on this executing ‘tino rangatiratanga’ account, Māori illustrate what much of the management literature believes to be essential in developing ‘good’ strategy. It is based on the view that understanding core values allows organizations to better guide their own destiny and create for themselves a sustainable competitive advantage (see, e.g., Hawken, Lovins, & Lovins, Reference Hawken, Lovins and Lovins1999; Cummings, Reference Cummings2002; Harmsworth, Reference Harmsworth2002; Henderson & Thompson, Reference Henderson and Thompson2003; Scrimgeour & Iremonger, Reference Scrimgeour and Iremonger2004; Miller, Reference Miller2005).

More specifically, in relation to the land and the natural environment, participants were keen to point out that Māori values differ from commonly held so-called ‘Western’ beliefs in a variety of ways. In this vein, kaitiakitanga – roughly translated as ‘stewardship’ or ‘guardianship’ – alludes to the relationship between Māori and the land and the natural environment. With an eye on the future it also speaks to intergenerational thinking. Many Western scholars have equated kaitiakitanga with sustainability, but kaitiakitanga includes additional elements not translated exactly in the English meaning of sustainability (Miller, Reference Miller2005). Below are two illustrative excerpts from discussions about kaitiakitanga with the participants and what meaning they attached to it.

So 50 years, the thinking is that that’s three generations. It is always about our tamariki and our mokopuna, so the ones that are here today and the ones that are coming. We have to make sure that in all our decisions that that is foremost.

The Māori word around sustainability is not to restrain but to enhance. So a fundamentally different way of looking at things, so how do we enhance and then empower this environment and the environment around it. And the interconnectedness of it all, so it is not just about the river, it is everything around it.

Interwoven with the concept of kaitiakitanga is the concept of mauri; this being the process that ‘binds the physical, spiritual and psychological aspects of all life’ (Tunks, Reference Tunks1997). As a value kaitiakitanga includes the maintenance of the mauri of all life and its utu (or ‘balance’). One participant shared their explanation of the relationship between these values and how it guides their business strategy:

At the very heart of it [Māori business strategy] is essentially our custom, ethos, belief, philosophy towards the natural world. So whilst we live in a modern world, deep down in Māoridom there’s the notion of Kaitiakitanga – guardianship, and that guardianship, the philosophy that flows from the creation story of Māori and that’s through our Papatuanuku, the earth mother, and Ranginui and the marriage, the children, the drama of that marriage and what happened to the siblings. So out of that, is our genealogy; it comes down to this day, and we respect the fact that all living things have a life force – they have a mauri. So if you believe in that concept, it is not difficult to be a – I suppose Pākehās would call it – environmentalist. I mean there are modern names for what we call, and in part, what we call kaitiakitanga – guardianship of all living things. And whilst it is not a written law, it is a philosophy of belief and the notion that we should leave this earth in a better state for the next generation than we left it.

Not surprisingly, some of the participants acknowledged that traditional values can be challenging to maintain or incorporate in a modern business context, largely because it was felt that they are at odds with a so-called ‘Western corporate model’, which typically prioritizes economic returns above all else. The majority of participants discussed this difference by relating experience or impressions from their time studying and/or working in Western institutions. They then made an effort to provide examples of how Māori values are difficult to maintain in the non-Māori world in which their organizations are competing:

I think [Māori values] come into play now more than ever. I think they are more needed now more than ever before, but that doesn’t make it any easier in terms of running a business.

Despite this, it was felt that although these values may be hard to incorporate while still delivering economic returns, if successful they might hold out the promise of comparative advantage for their business. A typical response was:

Our being Māori is our real point of difference. Our being Māori is our competitive advantage. And so we need to capitalize on that and build on it.

What might this involve? In general, and perhaps most obviously, it would come from an increased demand for products produced with a low carbon footprint provided by organizations with a strong social and environmental consciousness built into their DNA (Lash & Wellington, Reference Lash and Wellington2007). Culturally and historically Māori are well positioned to deliver on this. However, realizing comparative advantage will depend on many factors, one of which is how Māori values inform Māori perceptions of their role in climate change and how this might translate into their business strategy and business models.

On roles

Having first been asked to comment on what they think of when they think of climate change, participants were then asked to describe how their values inform perceptions of their own and, more specifically, that of their organisation’s role in relation to it. Based on current demographic and economic trends, Māori will increasingly be prominent in key sectors in the New Zealand land-based economy; combine this with their traditional kaitiaki role and one can begin to see some serious possibilities.

On this topic, however, there was greater diversity of responses. Some participants felt that achieving reductions in greenhouse gas emissions is in line with Māori traditional values, ‘I suggest that the ETS and its philosophies and what they’re trying to achieve, aligns very comfortably with traditional Māori values’. Other participants, however, felt that while Māori do have the traditional kaitiaki, role, they do not want to then be told by non-Māori how this should be realized through climate change regulation or policy that they see as having little connection with the environment. For example:

If climate change is the issue, then it is serious. But this whole ETS stuff focuses everybody’s attention away from climate change and onto money … when the real issue is are my kids going to be okay?

Against the backdrop of the rapidly increasing economic and social role of Māori businesses in New Zealand, participants were asked to reflect on what this might mean in terms of a leadership role on climate change. Reactions and responses to this question were mixed, but in various ways all participants expressed some surprise to this question, giving the impression that it was not an area that they may have considered previously, and even if it had, while there is recognition that Māori values might set them apart as an organization, this did not necessarily translate into a leadership position. Even if it did, significant challenges would have to be overcome before it became a reality.

I think the Māori role at the moment is heavily influenced by what non-Māori feel it should be rather than what we identify for ourselves. Because there are elements of our culture and the way we do things that could have contributed to some of the solutions for climate change and environmental sustainability.

I think there’s a role but I do not necessarily think that there’s a will for that [Māori leadership on climate change] to happen.

You’ve got people that want to say NZ is a leader overseas, and honestly we overrate ourselves. People do not give a shit. So instead of getting caught up in that we need to figure this stuff out on the ground.

We’ve done no real thinking on it.

These excerpts clearly illustrate that while ostensibly Māori values are very much in line with environmental action this is a long way away from being fully developed into any sort of coherent strategy to act on climate change or to gain competitive advantage from it. We submit that one possible explanation for this, explored in the next section, has to do with Māori perceptions of key norms or expected behaviours that might pertain to the situation.

On norms

In this context, and closely intertwined with values and roles, norms are simply defined as ‘expected behaviours’ (Checkland & Scholes, Reference Checkland and Howell1990: 49). For Māori stakeholders and their organizations the origin of these are a combination of those about them from their own Māori community and those from non-Māori, as well as their perceptions of norms for non-Māori or Pākehā. All of these impact upon what Māori believe their role should be, which is very often the one that is adopted. In Pākehā New Zealand society, negative stories about Māori promulgated in and beyond the media, have tended to be much more frequent than positive stories (see, e.g., Stuart, Reference Stuart2002). This so-called ‘deficit reporting’ on the underperformance of Māori institutions and/or people has, it is claimed, added to a norm of negative behaviour and statistics that, in areas such as unemployment, crime, and domestic violence, apparently bears witness to the deficiencies of Māori people and the poor reputation of entities associated with them. As a result, many Pākehā New Zealanders have negative expectations associated with Māori and Māori entities. This can create a demoralizing and self-deprecating norm for many Māori people (Chant, Reference Chant2009). This point was reinforced by participants:

You know the perception out there in Pākehā-land is that Māori are sort of… what you read in the paper, you could pick up the paper everyday and see a bad news story, usually about Māori, why – because the press loves to talk about something bad. And it is easier to do that than to talk about a Pākehā and so on. And there’s just as many bad Pākehā as there are Māori

Despite this, there is also an expectation that Māori will look after Māori. This is in line with traditional Māori values, and also part of the strengthening cultural ties over the last 30 years as part of Māori revitalization.

With our owners and beneficiaries, it is how do we support our marae. We have four marae in our rohe that we support.

So therefore our primary goal will be to try and build our people’s capacity and to build their ability to be self sustainable.

It doesn’t matter where you are in the world … those whānau connections … are always going to be there, until the day you die.

Another growing norm within Māori communities is the expectation of understanding traditional values and tikanga (customs). This has created a tension between Māori who have grown up learning those whānau connections and values and those that have not; this being evident even in the small variety of perspectives revealed in this research. As discussed in the section on values, there is a strong belief that you have to understand Māori values in order to understand Māori and Māori organizations and much has been done to this end. This has been part of what some consider to be a relatively recent Māori renaissance that sees younger generations being educated about Māori history, the language and traditional values. Despite this, as below, concerns about a divergence in perspectives between older/rural Māori and younger/urban Māori continue to be expressed.

We once had a wealth of kaumātua and now we do not. We talk about leadership all the time, and developing our rangatahi, but the problem is we’re going to have a gap of 10, 20, 30 years before they can take those roles, so we’re in a bit of a trough.

And for that generation, that bracket, in my view they were often, they never grew up in their rural communities. They had shifted away to the urban centres, so there was that misconnect back to those values and the land. So you’ll go around and talk to Māori people and some older Māori people will say absolutely, and others will say we’re not interested in money, what are we doing about our land, what are we doing for the future for our kids. But you’ll also get that from younger ones like your age.

Well again you have the old people, like some our shareholders, the vast majority of people who responded to our most recent survey, were 50 plus, and they have a different view of the incorporation than young people, older people are always thinking about the family or whānau (family) and the connection. But through that they expect a dividend but they use that dividend for education purposes for their kids or grandchildren or whatever. The top three things, or priorities, that were highlighted were dividend number one, land retention, and education grants.

Pressure for growth and quick returns, and that to me is the biggest thing, there are a lot of tribes around the country and a lot of that comes back to your upbringing and did you grow up on your marae (meeting house), do you have that tikanga (customs) ingrained, and a lot of people do not, a lot of Māori have gone and been Westernized. So we sort of need to be decolonized

At the same time, Māori have certain behaviours that they expect from non-Māori. Seemingly these often include condescension, and, as alluded to earlier, a short-termist, narrow, largely pecuniary-based, and a more individualist than communitarian view of business.

Money talks. The Pākehātanga (non-Māori way) is the dollar. For me it is a tool to achieve something. I do not believe in the dollar as a matter of course. I know that if I have a dollar I can achieve things and put that resource to use, but for the tikanga (customs) of the Pākehā (non-Māori), it is the mighty dollar.

So what you see in Māori businesses and Pākehā businesses that are trying to work with Māori businesses, they do not have that same mix, they will have savvy commercial managers and all the rest of it, but none of those underpinning values of Māori, and that’s what gets themselves into strife trying to do stuff with Māori, it is just different and they do not realize or appreciate the full difference

Summarizing this section, the proposition is that it is the mutually reinforcing combination of values, roles and norms that help to explain whatever worldviews underscore how people make sense of problem situations. However, in the case being discussed here, while the notion of a ‘Māori worldview’ or Te Ao Māori, might roll easily off the tongue, this is clearly not a singular concept. Some broad generalizations can be made, but it is important to acknowledge the diversity of perspectives that exist.

That aside, as far as climate change is concerned, it is clear that many Māori are seemingly sceptical about the basic idea. So while their traditional values may appear to align with contemporary mitigation and adaptation agendas, these are just one element of the overall worldviews that pertain to climate change. Hence while traditional environmental stewardship values may be a potentially important enabler of activity in this area, conversely roles and norms pertaining to business and business strategy can be significantly constraining. Most obviously this is the case if climate change is regarded as a largely Western political construct to further restrict Māori economic development thereby reinforcing systemic inequalities.

Phase 2: conceptual modelling

Following the initial set of interviews, each participant received drafts of their transcript in order to provide any further comment on the information that they shared. In addition each participant was asked to comment specifically on the areas identified as possible ‘transformation points’ that might be considered relevant to taking action in relation to climate change. The responses were then coded to identify common themes and patterns. Initially this resulted in nine ‘systems’ being chosen for possible modelling. Of the nine, five were selected, first for describing in more precise terms, and then for modelling. These systems were selected to best represent the diversity of viewpoints and potential transformation points expressed through the interviews. In the listing below, each one is described as ‘A system to … ’.

-

1. reduce business risks and maximize opportunity as a result of climate change to facilitate greater economic growth and maintenance of traditional values

-

2. capitalize on the point of difference for Māori businesses through certification/branding around climate change

-

3. create a new leadership role for Māori businesses and land owners on how to successfully incorporate climate change mitigation and adaptation into business strategy

-

4. reduce greenhouse gas emissions and promote economic development for Māori

-

5. achieve comparative advantage in the context of climate change by building scale in working together, kotahitanga (working as one)

Once such a listing of possible systems has been arrived at, and before conceptual modelling begins, each one has to be described in more precise terms. Conventionally, in SSM there is a particular technique for producing what are referred to as ‘root definitions’. Space limitations prevent describing these here, suffice to say that these exist to provide clarity and to specify more precisely within a particular set of environmental constraints, what the key transformation is, who enacts it, what worldview gives it meaning, and who is expected to benefit from it. All of this occurs during Stage 3 in the methodological sequence. Stage 4 then builds upon this by developing conceptual models that identify the activities that enact the transformation, as well as the sequences and dependencies involved. In other words according to a defined worldview these models portray what logically needs to occur in order for the system to do what is being claimed it does. But to repeat what was said earlier, while these abstract conceptual models are relevant to the so-called real-world they do not necessarily represent it. They might deliberately be designed in such a way, but the main use is simply to structure debate and assist with thinking about what action might be taken to address a given situation.

Two illustrative models

As before, space limitations preclude providing full details of all of what was done through this project. For that reason only two of the models used are described here. Their inclusion here is because the participants in the study considered that they were not only highly relevant to the situation in question, but also relatively feasible. This latter aspect is covered in the next section.

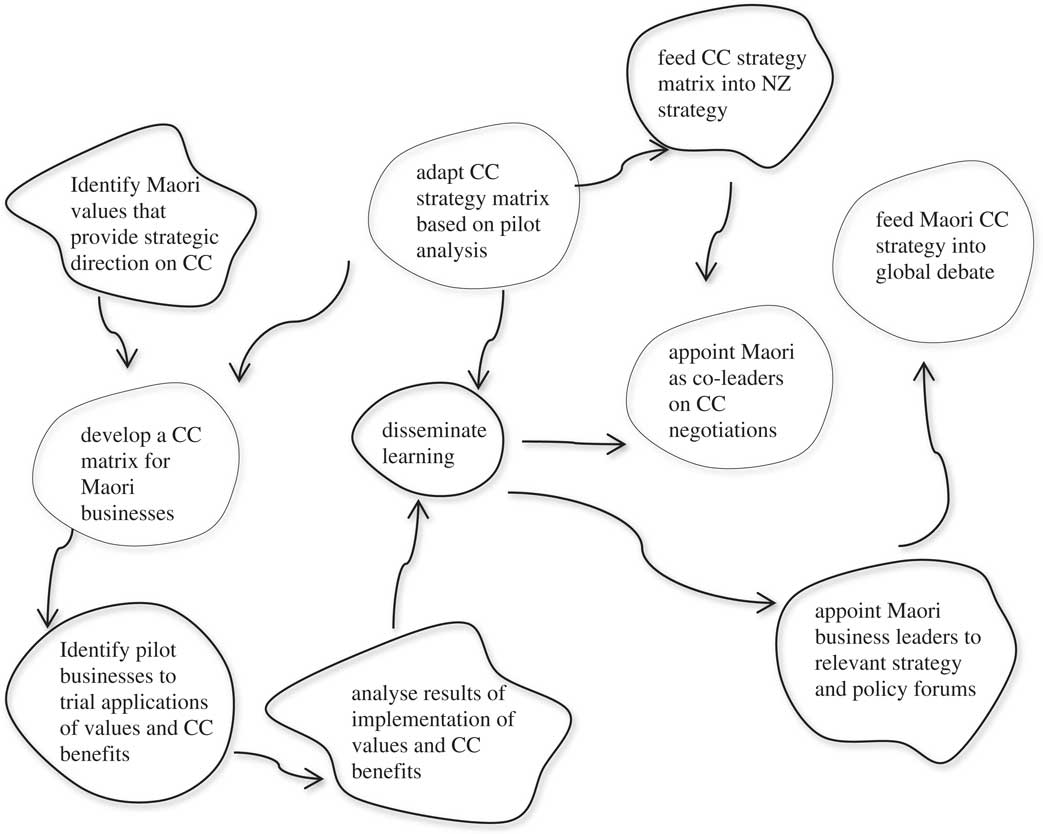

The first model illustrated here (Figure 1), addresses two areas of concern raised by the participants: (1) the deficit focus on Māori institutions/people and (2) the goal of economic development in line with Māori values. First, climate change provides a unique opportunity for Māori organizations to take on a leadership role given their values and history of sustainable resource management. This in turn would provide an opportunity for positive attention from the media and from non-Māori organizations that could feasibly learn from subsequent successes. At the same time, by leading the way on implementing mitigation and adaptation activities in land-based businesses; Māori organizations could gain comparative advantage through first- mover status, and thus promote further economic development.

Figure 1 A system to create a new leadership role for Māori businesses on how to successfully incorporate climate change mitigation and adaptation into business strategy

In simple terms, and without delving deeper into each activity (note that each one of these can be modelled in its own right as a entire system with its own sub-activities), the model activities begin by first identifying the values and traditional knowledge that might pertain to climate change and then consider how this would be applied in various land-based businesses to reduce emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. This would be followed by testing whether this implementation actually results in lower emissions and higher adaptive capacity. Once concrete practices/strategies were identified, Māori could feed this knowledge into the national and international policy discussions around climate change, thereby taking on a leadership role in this area.

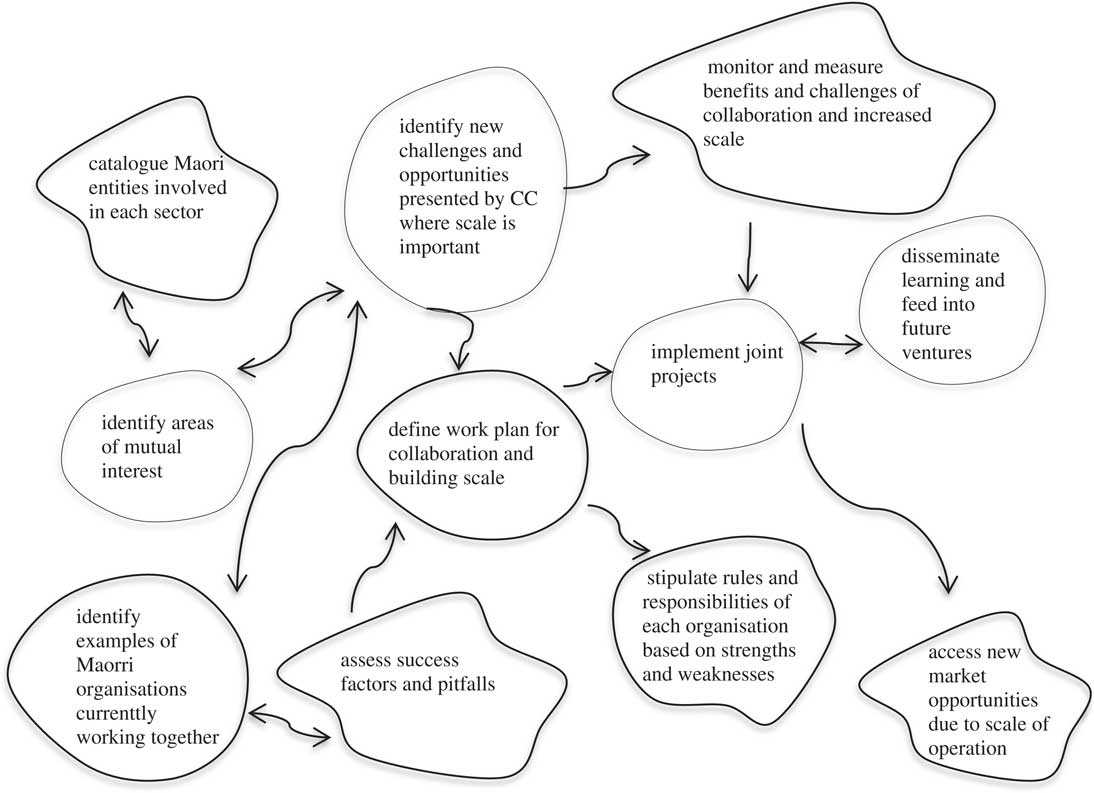

This second model illustrated here (Figure 2) was developed to address participants concerns about a lack of scale in entering new areas of business. Māori organizations are often owned collectively and Māori land blocks are typically smaller and dispersed, presenting obvious challenges for achieving economic scale and scale in addressing or benefiting from opportunities and challenges, in this case presented by climate change. In addition, working collectively is also a core component of Māori values, even though it can present considerable challenges. The above model then, is targeted as a transformation from not working together to achieve comparative advantage to working together to achieve scale in order to maximize both the ability to deal with the challenges and maximize the opportunities presented by climate change. The activities within the model are structured to first address where there may be areas of mutual interest and then to catalogue ways that Māori organizations may already be working together in some form. In addition to assessing the current barriers and success factors, identifying new challenges and opportunities presented for working together, will provide the basis for developing an action plan. Following the development of a plan, definition of roles and responsibilities for each organization will provide for the implementation of joint initiatives. Monitoring of the success and failures of each initiative will provide further learning and development for further initiatives and a mechanism for continual improvement. These lessons can then be shared more broadly in order to maximize the potential for Māori organizations to achieve comparative advantage by building scale in working together.

Figure 2 A system to help build comparative advantage by building scale through working together

Putting the models to work

As we have said, the purpose of developing conceptual models is to have a point of reference to compare with perceptions of the ‘real world’, and in doing so to identify desirable and feasible areas for action (SSM Stages 5, 6, and 7, respectively). There are various ways of doing this. However the approach taken here was to first ask the participants to rate each system in terms of its relevance and feasibility and to explain these. While, as has already been said, the two models outlined above were considered to be both relevant and feasible, this was not universally the case, some often being one but not the other. Some participants for example considered that climate change could present a unique opportunity to identify an area of common purpose among Māori organizations; however it was felt that this would take significant effort and time. Equally capitalizing on the point of difference of Māori organizations from a branding or certification scheme was also viewed positively but it was not prioritized because it was felt that there would be a significant amount of other transformations that would need to be accomplished first.

Participants were then asked to list the activities and actions that they are already conducting and/or might plan on conducting to achieve the transformation in question. These were then compared with the activities listed in each model. In SSM this ‘real world interrogation’ process can be done in different ways and with varying degrees of formality (see, e.g., Davies & Ledington, Reference Davies and Ledington1991). Here a relatively informal semi-structured approach was taken that involved questioning along the following lines:

-

1. Do the activities listed in the model actually occur ? If yes, in what way/how? If not, why not?

-

2. Who is involved in these activities?

-

3. What resources such as money, materials, technology, and skills are drawn upon in carrying out the activity?

-

4. How is the activity planned and controlled and by whom?

-

5. How well is it done?

Using one of our models as an example, and in order to provide a very basic insight into how this aspect of the process works, Table 2 shows some of the initial high-level responses to these questions.

Table 2 Comparing and contrasting

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

At the outset it was said that given their current and growing asset base and their unique values related to land, resource use, and enterprise, it is clear that not only do Māori have an interest in climate change mitigation and adaptation, it also has the potential to be capitalized upon to promote economic and hence social development. However since the participants had not thought seriously about this, if at all, it was necessary to take one step back and investigate what it would take for Māori to first see and then consider how competitive advantage might be realised. Using SSM as a framework for working with the leaders of Māori entities this has involved thinking about how their roles, values and norms inform how they engage with the topic under consideration, and then using abstract models generated through interviews and discussion to structure debate on what actions, for them, might be both desirable and feasible.

Although it is hard to say conclusively that this approach was successful, the feedback was positive. For example, at the beginning, one participant said: “I think climate change is all a lot of bull, (it) is just a marketing plan for somebody to create an economic advantage”.

At the end of the project the same person remarked:

I think climate change can help people realize what they’re doing, that they’re affecting their environment, and I think it is making us look back on how we do things. We’re a throwaway society, we do not utilise things for long, and so we need to say, how can we make this into an opportunity?

Another participant who thought that they were being asked something different at the start of the research to what he understood at the end said:

But you saw my reaction when you asked the initial question. I couldn’t quite sort of hook into what it was you were actually looking for, but after you articulated it more and I saw the models, then yeah straight away I see the connections.

At the very least the process did allow participants to engage with and think somewhat differently about climate change. At the outset, and unsurprisingly, many participants were preoccupied with the need for changes in Crown policy especially in areas such as education, employment, health, regional development and crime/justice. For some, putting climate change on the agenda would only add to an already overwhelming number of competing priorities within Māori institutions. Later however, as things began to settle down and the kernel of possibilities began to quietly bubble to the surface it became clear that it was not entirely fanciful for these leaders to speculate that they had missed something and that there might just be opportunities that their organizations could usefully explore. It was now clear however, that this was neither the time nor place to drill down and generate substantive proposals. For a start, the time allocated to the project was almost exhausted so even if more detailed work was put on the agenda, logistically, delivering on this would have been difficult. More importantly, we were acutely aware that these Māori organizations have much stronger systems of participative governance and community involvement than do most comparable sized Western businesses. So although we set out with a different view, we considered it more than acceptable to seed the idea of a possible reframing, or new ‘direction of travel’, in relation to climate change than to seek to push things to a point where our leaders might develop proposals that might subsequently fail to pass the test of community endorsement.

Moreover, even where a proposal has community backing, traction in the market place is the ultimate goal, so even the most creatively thought out and ostensibly plausible proposition still has to be well conceived and subsequently tested in the market place, all of which takes time. How this might be done in particular cases is beyond the scope of this paper; suffice to say that the innovation and strategy literatures are replete with frameworks that, depending on circumstances, can be drawn upon either singly or, depending upon circumstances, in creative combinations.

One such approach that seems to befit the collective governance processes favoured by many Māori organizations including the ones involved here, is to draw upon classic strategic concerns such as environmental analysis, competitive positioning and building upon existing resources and capabilities, but initially to do so in a manner that privileges visual drawings and pictures over detailed written documents and plans. Further down the track, when the focus shifts from broad strategic direction to the more detailed aspects of strategy and business models, visuals – including quantitative ones – can be highly effective in orienting and animating collective debate (see, e.g., Osterwalder & Pigneur, Reference O’Sullivan and Dana2010; Sibbet, Reference Sibbet2013; Cummings & Angwin, Reference Cummings and Angwin2015).

Of course this does not mean that opportunities and actions so identified will be implemented or indeed be successful if they are. Some will fail simply because with limited resources and high levels of uncertainty it makes sense for these organizations to adopt a simple low-cost ‘safe-to-fail’ experimental approach to market testing. Given the risks involved, in the first instance it is surely much better for these organizations to adopt this ‘design thinking’ type approach to business opportunities, than prematurely and/or over-committing to expensive large scale projects based upon detailed plans.

Beyond this, there are obviously numerous other constraints that, depending upon the nature of the proposal, may need to be carefully thought about and managed. Most obviously the long history and relationships between iwi, trusts, incorporations and individuals within Māoridom rings some warning bells in relation to the collaborative, scale-building conceptual model illustrated earlier, and which is increasingly evident in successful business models. Today, rarely is it possible for organizations to fulfil all of their objectives on their own, so partnerships of one sort or another are increasingly necessary. And central to this concern is that while Māori may understand that working together either to build scale, or to fit the different pieces of a proposal together, cultural and historical barriers may need to be addressed. As one participant put it:

If Māori can get their act together, working on the assumption that Māori will work with Māori. There’s plenty of opportunity for us to do business with each other, but Māori are still tribal. You’ll hear people all around the country saying Māori need to work together, yeah of course they do, but we also have long memories. You know back in 1835 when your tribe killed someone in my tribe and then my tribe bopped you, things like that. Cause at the end of the day we’re human, and what makes logical sense isn’t always what happens.

In similar vein, while the participating organizations may decide that it is to their benefit to take the steps outlined in the models illustrated in the paper, some of the areas identified for transformation will require action by a range of external stakeholders including funding bodies, research institutes, universities and others. Despite the attempts that were made through the project to not focus undue attention on the role of the Crown, it is hard to escape its importance. In fact, although the environmental constraints differed slightly for each model, the principal factor that continued to emerge was the relationship between Māori organizations and the Crown. Despite the economic advancement of many Māori businesses and significant progress in the area of treaty settlements, there continues to be an element of distrust and a perceived lack of transparency from the Crown in their relationship and policymaking concerning Māori. For example:

It is not well understood [the potential role and comparative advantage of Māori] because this sort of level of conversation doesn’t necessarily take place between the two communities [Pākehā and Māori]. It is only in the last 25 years we’ve had serious conversations about serious matters. And it is been our generation that have forced that. And I say forced, because it hasn’t come about through the volition of the majority, hasn’t been Pākehās who want to talk about difficult things or philosophies or whatever. I’ve said to them, Well you guys have extracted your economic rent and you want us to provide ours for free. I do not think so, I’m happy to accommodate, but there’s a cost.

More specifically, since: ‘we have suffered from policy regulation that was put in place which 100 years later has not been effective, hasn’t met its purpose, and the only people that have lost are Māori’, the perception seems to be that the Crown’s current policies on climate change will likely be no different.

If this view has any real currency, for the Māori organizations included in this research and for others, achieving comparative advantage in the context of climate change will certainly be dependent on the organizations themselves. However it will also be heavily influenced by how the Crown’s policies allow for, and/or facilitate exploiting the unique value of Māori in that particular context. And this might depend substantially on perhaps the most important transformation of all which is to begin by better seeing the comparative advantage of Māori as a people.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to offer sincere thanks to the Māori businesses and their representatives who participated in or facilitated this project.