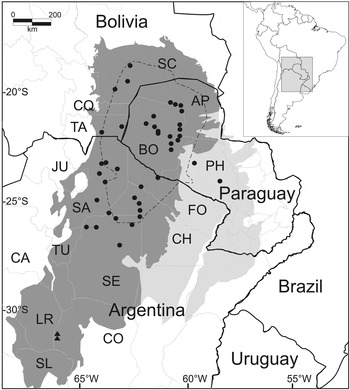

Among the three extant species of peccary the Endangered Chacoan peccary Catagonus wagneri(Altrichter et al., Reference Altrichter, Taber, Noss, Maffei and Campos2014) is the rarest and the most threatened. The species was first described by Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1930), as a subfossil, and was rediscovered as an extant species in Paraguay by Wetzel et al. (Reference Wetzel, Dubos, Martin and Myers1975). Later, the presence of the Chacoan peccary was confirmed in the Paraguayan departments of Boquerón, Alto Paraguay and west of Presidente Hayes, in western Formosa, northern Chaco, eastern Salta and the far north of Santiago del Estero provinces in Argentina, and east of Tarija and south of Santa Cruz (and probably east of Chuquisaca) provinces in Bolivia (Mayer & Wetzel, Reference Mayer and Wetzel1986; Taber, Reference Taber and Olivier1993; Chébez, Reference Chébez2008; Maffei et al., Reference Maffei, Cuéllar and Banegas2008; Fig. 1). Thus the known distribution of the species is restricted to the north and centre of the driest portion of the Chaco ecoregion. However, distribution models fitted only with occurrence localities from Argentina (Torres & Jayat, Reference Torres and Jayat2010) showed that suitable habitats extended further south to the province of Córdoba in central Argentina. Here we present the first two records of the Chacoan peccary in the province of Córdoba and report several records 100 km or more beyond the limits of the currently accepted distribution (represented by the IUCN polygon, i.e. the polygon depicting the distributional area according to the criteria of IUCN experts; Altrichter et al., Reference Altrichter, Taber, Noss, Maffei and Campos2014).

Fig. 1 Distribution of occurrence localities of the Chacoan peccary Catagonus wagneri from museum collections and the literature (circles), and the two new records reported here (triangles). The Dry Chaco ecoregion is shaded in dark grey and the Humid Chaco in light grey. The IUCN polygon (Altrichter et al., Reference Altrichter, Taber, Noss, Maffei and Campos2014) is delimited by a dashed line, representing the currently accepted range. Sub-national political boundaries are indicated only in those countries where the Chacoan peccary is present. SC, Santa Cruz; CQ, Chuquisaca; TA, Tarija; AP, Alto Paraguay; BO, Boquerón; PH, Presidente Hayes; JU, Jujuy; SA, Salta; FO, Formosa; CH, Chaco; SE, Santiago del Estero; TU, Tucumán; CA, Catamarca; LR, La Rioja; CO, Córdoba; SL, San Luis.

The first record from Córdoba is a skull of an adult of unknown sex hunted in 2013 in the west of the province, c. 10 km west of El Cadillo, which we collected on 29 March 2015 and later deposited in the Mammal Collection of the Museo de Zoología of the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Supplementary Material 1). The skull was incomplete, lacking the lower jaw, but most of the cranial diagnostic characters (Mayer & Wetzel, Reference Mayer and Wetzel1986) were evident: rostrum and nasal chambers more pronounced, a proportionately smaller brain-case, a deeper zygomatic bar below the orbit, and a more posterior position of the orbit (with its anterior edge located well posterior to the last molar) than in the other peccary species; the infraorbital foramen well anterior to the zygomatic arch; and the lack of a pronounced articular fossa on the anterior face of the zygomatic arch (Plate 1). On 19 July 2015 we photographed a skull of an individual that had been hunted in Estancia Pinas in 2003, c. 20 km from the locality of the first record (Plate 2). Both records were c. 650 km south-west of the IUCN polygon. The individuals were hunted in secondary forests typical of the southernmost Dry Chaco ecoregion (sensu Olson et al., Reference Olson, Dinerstein, Wikramanayake, Burgess, Powell and Underwood2001), with Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco as the emergent tree, Prosopis flexuosa, Cercidium praecox and Ziziphus mistol dominant in the tree stratum, Celtis ehrenbergiana, Larrea divaricata, Mymozyganthus carinatus, Acacia furcatispina, Acacia praecox, Opuntia sulphurea and Opuntia quimilo as the main components of the shrub stratum, and Deinacanthon urbanianum as the most abundant grass in the herbaceous stratum (Cabido et al., Reference Cabido, Manzur, Carranza and González Albarracín1994).

Plate 1 Lateral, ventral and dorsal views of the skulls of a Chacoan peccary Catagonus wagneri (MZUC-I00429) hunted 10 km west of El Cadillo, in the province of Córdoba in central Argentina (left) and of a collared peccary Pecari tajacu (MZUC-I00435) from La Paquita, in the province of Córdoba (right).

Plate 2 Skull of a Chacoan peccary hunted by local people in Pinas, west of Córdoba province, Argentina, in 2003.

These findings were part of the results of 18 semi-structured interviews (Guber, Reference Guber2011; Valles, Reference Valles2014) that we conducted during March–August 2015 in seven rural communities in an area of 751 km2 in the west and north-west of Córdoba province to gather information about the Chacoan peccary. Questions focused on the respondents’ ability to distinguish the species, knowledge about its habits, and frequency of sightings. Seventy-two percent of the respondents mentioned this peccary species (known locally as chancho moro) as part of the local fauna. They were able to distinguish this species from the collared peccary Pecari tajacu, the only peccary species previously recorded in Córdoba (Morando & Polop, Reference Morando and Polop1997). They described it as a long-haired species, and bigger, faster and less gregarious (solitary or in pairs) than the collared peccary; all these characteristics are in agreement with the description of the Chacoan peccary. The fact that another species recorded recently in the same area, the lesser anteater Tamandua tetradactyla (Torres et al., Reference Torres, Monguillot, Bruno, Michelutti and Ponce2009), was recognized by only two respondents and does not have a local name despite its striking appearance suggests the Chacoan peccary is not necessarily a recent immigrant.

We searched for records of the Chacoan peccary in museum collections and in the literature (Supplementary Material 1), and used maps, gazetteers and Google Earth (Google Inc., Mountain View, USA) to determine their geographical location. Museum databases often include the geographical coordinates of records, but locations are often approximate. We revised and improved these data for almost all records. We found a total of 53 presence localities for the species, attributable to a given location with an error < 5 arc-minutes. Two localities were within the Humid Chaco (Fig. 1), 14 (26%) were outside the IUCN polygon, and six (11%) were > 100 km from the polygon limits, including our new records in Córdoba (Fig. 1).

Our findings highlight the need for further field research and biodiversity inventories in central Argentina, particularly in areas with Chaco forests. This is also an example of the value of local knowledge to researchers. Local people have long known of the presence of the Chacoan peccary in central Argentina, and its presence should not be surprising given that the environment in western and northern Córdoba is similar to that described for the species. In another example, the Chacoan naked-tailed armadillo Cabassous chacoensis was recorded in central-western Argentina, far from the nearest known presence locality in the north of the country (Tamburini & Briguera, Reference Tamburini and Briguera2013 and references therein), although the species and its biology are well known by local inhabitants, who have historically used it as food.

Although there is no information about the existence of the Chacoan peccary in the area between Córdoba and the region covered by the IUCN polygon, it is possible that the population in Córdoba is not isolated. There is continuous forest linking both areas, as shown by the most recent land cover classifications (Morales Poclava et al., Reference Morales Poclava, Lizarraga, Elena, Noé, Mosciaro and Vale2007; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Aide, Grau and Riner2010), with climatically suitable conditions (Torres & Jayat, Reference Torres and Jayat2010).

Even if the presence of the Chacoan peccary is confirmed in those areas linking Córdoba with the rest of its known distribution, we believe that the current international and national conservation status should not be changed. The Chaco ecoregion is threatened by land-use change (Grau et al., Reference Grau, Gasparri and Aide2005; Aide et al., Reference Aide, Clark, Grau, López-Carr, Levy and Redo2012), and deforestation rates in Córdoba province are among the highest in Latin America and worldwide (Zak et al., Reference Zak, Cabido, Cáceres and Díaz2008). Furthermore, the Chacoan peccary is heavily hunted by local people in Córdoba, as in the rest of its distribution (Altrichter et al., Reference Altrichter, Taber, Noss, Maffei and Campos2014). However, we believe there is still an opportunity to conserve this population, considering the connectivity with similar habitats further north. Accordingly, we consider that the presence of this Endangered species could be used as an important justification for protection of the remnant forests in Central Argentina.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Eulogio Quiroga, Abraham Quiroga, Nicolás Flores and Nicolás Rodrigues for their help with field work. We also thank the following curators: Sergio Bogan (Fundación de Historia Natural Félix de Azara), Janet Brown (Oklahoma Museum of Natural History), Mónica Díaz (Fundación Miguel Lillo), David Flores (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales Bernardino Rivadavia), and Itatí Olivares and Diego Verzi (Museo de Ciencias Naturales de La Plata). Some occurrence records were obtained from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility database. This work was partially funded by Fondo Nacional de Ciencia y Técnica, Argentina (FONCyT, PICT No. 1693-2006) and Secretaría de Ciencia y Tecnología, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina (Grant N° 1565–2014).

Biographical sketches

Ricardo Torres's research focuses on the application of species distribution models to mammal conservation in South America. Daniela Tamburini and Enzo Rossi are interested in the biology of mammals, particularly Xenarthrans, in Central Argentina. Julián Lescano studies anthropogenic factors affecting wildlife in central Argentina.