Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an increasing health problem that affects about 600 million people globally, and it is expected to be the third most common cause of death worldwide by 2020. The morbidity and mortality risk in COPD results in both economic and social burden, which is a considerable and increasing problem for society, as well as for the affected individuals and their families (Global Initiative for Chronic Lung Disease (GOLD), 2008). COPD is strongly associated with smoking habits, which is by far the most commonly encountered risk factor for COPD (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Bjerg-Bäcklund, Rönmark, Larsson and Lundbäck2006). COPD is characterized by a slow progressive deterioration; the impaired lung function is irreversible. The symptoms are mainly shortness of breath, coughing, sputum production, fatigue, and weight loss (GOLD, 2008). In the end stage of COPD, there are difficulties in managing everyday life and day-to-day activities cannot be carried out; the patient becomes increasingly dependent on others (Ek and Ternestedt, Reference Ek and Ternestedt2008). To a great extent, the primary carer of a person with a chronic disease is a relative, and the person is cared for at home. Women are much more likely than men to be caught up in heavy caring by providing personal care and performing other caring tasks. It is important to take into account the needs of support for both carers and care recipients, and their needs should be seen as a whole in the social care system (Jegermalm, Reference Jegermalm2006).

Chronic illness is not only a problem for the person who is ill, but also affects the spouse, and both the present and the future will be changed (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz1997). Sharing everyday life with someone who is chronically ill may mean less opportunity for rest, privacy, and freedom. The need for help from the care recipients is sometimes boundless, and it can lead to difficulties for spouses, because their life is in some cases dictated almost entirely by the care recipient's needs and it is difficult to find free zones (Jeppsson Grassman, Reference Jeppsson Grassman2003). Spouses suffer significantly, experiencing severe anxiety and helplessness as they witness their partner's suffering and feel powerless to reduce it (Booth et al., Reference Booth, Silvester and Todd2003). Previous studies on the impact of caregiving on health have shown that caregivers were at high risk for psychological and other health-related problems. Caregivers were more stressed, depressed, and had lower levels of subjective well-being and physical health (Pinquart and Sörensen, Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2003; Reference Pinquart and Sörensen2007; Vitaliano et al., Reference Vitaliano, Zhang and Scanlan2003). Feelings of loss and grieving, psychological distress and depression can occur (Cain and Wicks, Reference Cain and Wicks2000; Bergs, Reference Bergs2002; Kara and Mirici, Reference Kara and Mirici2004; Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Holanda, Medeiros, Mota and Pereira2007).

A literature review (Lindqvist et al., Reference Lindqvist, Håkansson and Petersson2004) showed that women who are informal caregivers to chronically ill persons give significantly more demanding and complex care than men, and have difficulties in balancing family life, employment, and social life. The female caregivers reported deteriorated health to a higher extent, and they were more physically and mentally affected than men in the caregiving role. Bergs (Reference Bergs2002) showed that the assigned role of the sick partner changed the partnership and the healthier spouse had to take over more responsibilities, which led to restructuring of roles and created confusion and insecurity. The caregivers’ own health problems created a concern that they may not be able to give the relative the help they needed (Gysels and Higginson, Reference Gysels and Higginson2009).

Persons with mild to severe COPD are in Sweden, usually managed in primary health care, while very severe COPD cases, especially if treated with oxygen therapy, are managed in hospital clinics. Otherwise, the patients are in their homes, and only in the event of acute deterioration, for example infections, are they admitted to the hospitals’ pulmonary wards. The length of hospital stay has decreased in the last few years, and most people with COPD are cared for in their homes with follow-ups in primary health care or the pulmonary department at the hospital. In recent years, pulmonary rehabilitation programmes or COPD schools have been developed in many countries for patients and their spouses to learn to manage to cope and live with the effects of COPD. On a number of occasions, the managing team teaches about the disease and its management, self-care, pulmonary rehabilitation, cough and inhalation technique, nutrition, exercise, etc. (Heart and Lung Association, 2009). For practical matters, a person with COPD can get mainly tax-funded home service, with fees depending on the person's income and what municipality he/she is living in. Many people generally refrain from using home service, because they think it is too expensive (Szebehely, Reference Szebehely2003). Relatives are seen as a resource by society, and thus the pressure on the spouses and relatives will increase, because of restraints in home service with higher fees and stricter assessments of the needs of patients and spouses (Szebehely and Ulmanen, Reference Szebehely and Ulmanen2005). Thus, spouses increasingly take the caring responsibility for their COPD sufferer. The assistance that informal caregivers can receive is a support group for caregivers, respite care at home, and practical help with household tasks and home modifications, information from healthcare professionals and participation in COPD school (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2010). Psychological/psychotherapeutic support is seldom offered to people with COPD in Sweden, which means that it is rarely offered to the informal caregivers either (Lindqvist and Hallberg, Reference Lindqvist and Hallberg2010).

No previous studies have been found on the conception of daily life in women living with a man suffering from COPD at different stages of the disease. However, there are studies focusing on the quality of life of women living with a man affected with COPD. It has been shown that women lack opportunities for recreation and support from friends, family, and health professionals (Bergs, Reference Bergs2002). Carers of persons with severe lung disease were affected by severely restricted lives and they felt frustration and were heavily burdened. It was important for the spouse to have a part-time job in order to reduce both the isolation and the economic burden (Brewin, Reference Brewin2004). A study focusing mainly on persons with severe COPD and four spouses showed that household tasks and heavier work were left for the spouses to handle (Kanervisto et al., Reference Kanervisto, Kaistila and Paavilainen2007). As the COPD progresses, the relationship is affected, with a decrease in shared activities and less time being spent together as a couple (Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Young, Donahue and Rocker2010).

Seamark et al. (Reference Seamark, Blake and Seamark2004) focused on patients’ experience of living with severe COPD and the impact on their relatives who took on several roles as the illness progressed, and found that they experienced the same losses as the patient. When studying the family's perspective on adjustment and social behaviour of older adults with severe COPD, it was clear that the caregivers were dissatisfied with leisure activities, and that relatives of chronically ill men experienced more dissatisfaction with socially expected activity performance than did relatives of chronically ill women (Leidy and Traver, Reference Leidy and Traver1996). COPD is a progressive disease, and thus it is important to study conceptions related to the different stages in order to deepen the understanding of the informal carer's situation.

Aim

The aim of the study was to describe conceptions of daily life in women living with a man suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in different stages.

Methods

Design

This study had a descriptive qualitative design and used a phenomenographic approach (Marton, Reference Marton1981; Marton and Booth, Reference Marton and Booth1997). The method was chosen in order to explore the variety of ways in which something was conceived and viewed by the women. Phenomenography distinguishes between the first-order perspective, the actual state of something, and the second-order perspective – how a person conceives something or how something appears to them. Phenomenography describes conceptions using the second-order perspective. Conceptions are essential in phenomenography and are based on variations in people's awareness of the surrounding world. Marton (Reference Marton1992) describes phenomenography as a research method designed to describe the qualitatively different ways in which a phenomenon is experienced, conceptualized, or understood, based on an analysis of accounts of experiences as they are formed in descriptions.

Participants

Included in the study were women living together with men who had been diagnosed with COPD at different stages, mild to severe, and with the exception of men with continuous oxygen treatment and very severe COPD, which is the end stage of the disease (GOLD, 2008). Twenty-one women, aged 53–84 years (median 72 years), were included (Table 1). A purposeful sampling procedure was used. The women were recruited from two hospitals, different healthcare centres, and patient associations. Information was given to health professionals and chairmen of patient associations to strive to recruit female spouses of men differing in the stage and duration of COPD, in age and place of residence, in order to maximize variation in conceptions (Marton and Booth, Reference Marton and Booth1997). The head physician and managers of the departments received written and oral information about the study and gave their written approval. When the men suffering from COPD visited the hospital, the healthcare centres, or the patient association, they received a letter of invitation to join the study from the nurse or chairman and were asked to invite their spouses to participate in the study. The wife then sent a letter of consent to the first author.

Table 1 Description of female participants in the study

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

1Values are median (range).

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews (Marton and Booth, Reference Marton and Booth1997) between August 2008 and May 2009. An interview guide was developed on the basis of the literature and was peer reviewed by researchers/nurses who were experienced in chronic disease management. The entry question was ‘How is a typical day for you?’; this was followed by follow-up questions, for example ‘What effect has it had on you that your husband got COPD?’ (see Appendix 1). Two pilot interviews (included in the study) were conducted and functioned well and led to no changes in the interview guide. Fifteen interviews took place in the participants’ homes, one at a participant's workplace, and the other five at a university office. A nurse (first author) with experience in the field conducted all the interviews. Each interview lasted 40 to 120 min, was tape-recorded, and transcribed verbatim.

Ethical considerations

The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration, and with written informed consent from the participants (World Medical Association Declaration, 2008). According to Swedish law at the time of the study, ethical approval was not required for research studies that did not pose a physical or mental risk to the informants (Swedish Health Care Act, 2003).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the phenomenographic procedure described by Sjöström and Dahlgren (Reference Sjöström and Dahlgren2002), which has seven steps. (1) Familiarization: each transcribed interview text was read through and the tape-recording was listened to several times to give an understanding of the meaning of the content and a sense of the whole. (2) Compilation: the most significant statements given by each participant were identified and questions were asked about the text. (3) Condensation: longer statements were reduced to find the core of each dialogue. (4) Grouping: answers that appeared to have similarities were brought together. (5) Comparison: selected statements were compared to find variations and establish categories that were distinct from each other, and the preliminary analysis was reviewed. (6) Labelling: each category was given an appropriate label to express the essence of the understanding of its content. (7) Contrasting: the categories were compared and contrasted to find the unique characteristics of each category.

Rigour

In phenomenographic research, the core question of credibility is about the relationship between the empirical data and the categories for describing ways of experiencing a certain phenomenon (Marton, Reference Marton1981; Marton and Booth, Reference Marton and Booth1997). The credibility of this study is ensured by the way similarities and differences between the participants are supported by the empirical data. In a group of people, there are a limited number of ways of conceiving a phenomenon; with 20–25 participants, the variations are likely to be covered (Marton and Booth, Reference Marton and Booth2000). The co-authors double-checked the content of the categories to verify the relevance. In accordance with Sjöström and Dahlgren's (Reference Sjöström and Dahlgren2002) advice, a precise description of each part of the research process is given, and quotations from the interviews are provided so that the relevance of the categories can be judged.

Findings

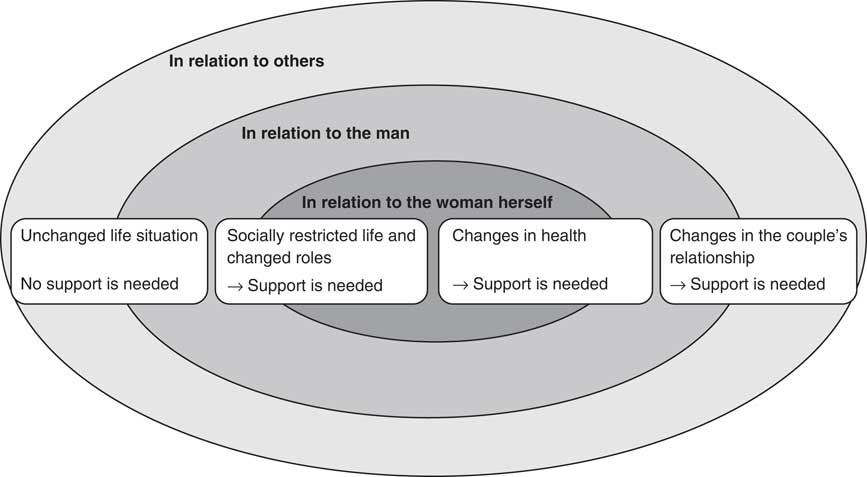

Four descriptive categories were found: (1) unchanged life situation where no support was needed; (2) socially restricted life and changed roles where support is needed; (3) changes in health where support is needed; and (4) changes in the couple's relationship and their need for support. The categories were described from three perspectives: in relation to the woman herself, in relation to the man, and in relation to others. The outcome space is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The four descriptive categories described from three perspectives, regarding the varying conceptions of women's daily lives together with a man suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease represents the outcome space.

Unchanged life situation

For some of the women whose men had mild COPD, their daily lives were unchanged from before the men became ill. They did not consider that the disease had affected life in any way, and they could do what they wanted to do. The resources they had were enough and no support from others was needed.

His illness doesn't affect my day at all; I live my life. I can work, so at the moment I don't need any help because things are functioning. (9)

Socially restricted life and changed roles

In relation to the woman herself

Some women were so focused on the man's disorder and needs that they forgot their own needs and began to feel increasingly isolated; they lost their independence and gained an increased sense of responsibility. They felt loss of freedom and spontaneity in their daily lives. The lost social contacts affected the women's daily life; they were forced to live a different life than planned. Some women, especially when the COPD became more severe, had to understand that their own lives would not be as they had planned, and that the disease would govern their life and support was needed. As the disease escalated, everything was affected; it dominated their life and they had to plan their daily routines, and they had no time for themselves.

My husband's illness fully dominates our daily routines. I get hardly any time of my own. (3)

In relation to the man

Some women believed they were unable to leave their home as they felt anxious about what could happen to their husband. A feeling of being a guardian instead of being a spouse sometimes arose when the disease progressed, and daily life was ruled by the man's condition.

I'm afraid to leave him alone and I have to do just about everything… I feel more like a caregiver than a wife… I have to be a little bit like a guard. (12)

They found that the disease was unpredictable; they could have planned something together but had to change it because of the disease. The women became aware that COPD is a progressive disease, and the future seemed out of control, and thus only short-term goals could be set. They were living more in the present because of the COPD. When they performed activities together, they had to be careful that it would not be too tiring for the man.

The COPD gets worse gradually, … we do a lot together … if disease lets us. I have to think about whether he is up to it and I have to listen closely to his breathing … We have to live in the present. (1)

Being able to travel depended on the state of the disease. At the beginning of the disease, they planned the trips very carefully but later on they could not travel at all. They avoided destinations with exhausting fumes or strenuous landscapes, and chose comfortable ways of travelling and brought a lot of medications with them. They had to take into account the fact that there might be a risk of infection for the spouse, as they knew it could worsen the spouse's condition. Meeting places where many people gathered, for example concerts, were avoided. The COPD problems could suddenly increase and the women felt uncertain of how to handle it, and it created distress for them.

We must always think about where to travel. We can't just go to any environment. There's a lot of planning. When we go somewhere, we must take a lot of medicines with us. (6)

We are aware of the fact that there is a risk of infection… of course one avoids crowds if one knows… (16)

In relation to others

The man's coughing was a source of irritation and they felt that other people were disturbed by it. Social contacts became limited as the disease progressed and the responsibilities increased. The women were so busy with their concern and care for their spouse that they withdrew from friends and activities, which limited their social life.

I can't leave him for long, … I have to help him all the time. I can't do anything myself… and meet other people. (3)

Most of the women felt that health professionals did not communicate with them. No one asked them how they were managing at home, whether they had the strength or needed support. They felt that it was taken for granted that they would take care of everything. They felt ignored, and they were left alone to take full responsibility for the situation. Only three women had been informed on one occasion by their doctor about their spouse's COPD, three couples attended COPD school, and two received aid in terms of a shower instead of bathtub and a special bed. In addition to this, they did not report receiving any support. Some women had the strength and ability to seek information themselves in order to increase their knowledge about the disease.

I've lost faith in healthcare. Nobody has given me information. I have nobody to turn to… I must take all the responsibility. (7)

Even when the man was cared for in the hospital, some women felt ignored and sensed that they were disturbing the staff.

Nobody at the infirmary explained anything. I asked, they sat there with their computers and I felt that I was in their way. They never made contact with me. (15)

Smoking was found to have negative consequences for the couples. Some felt ignored and were told by others that COPD was self-inflicted. Sometimes they had to defend themselves by arguing that if they had known it was so dangerous they would not have smoked. Smoking was conceived as a loaded word together with COPD. If they did not smoke they had to explain that it was caused by something else.

They haven't said straight out, but the implication is that COPD is a self-inflicted illness. (7)

They wished for understanding, information, and emotional and practical support from health professionals and local authorities. The women felt their spouse would be unable to live at home without them. As soon as the spouse had left the hospital or healthcare centre, the women conceived that they had all the responsibility for the care; no one cared about how things worked out at home. The women ended up in the caring role without having decided it themselves, and no one asked them whether they could manage it. The women felt concern about what would happen if they could not cope.

We have never talked about the situation at home. No one cares. When I don't have the energy, it won't work. I have never been offered information… or some support, some emotional support would be good. The person at home never gets anything. (20)

The grants for medications and medical visits did not cause any economic problems, as the high-cost ceiling covered the costs. Only one spouse had home service, and two had ended it because of the costs. However, most of the women refrained from home service because of the high cost, and regretted that they could not be supported with heavy duties that they felt they needed help with.

Home help costs a bit, and unfortunately we had a bad experience … they charged a huge amount … high-cost protection helps a lot. (5)

Changes in health

In relation to the woman herself

The women's own health problems had an impact on how they conceived their caring situation. They developed strategies to manage daily life to maintain their health and well-being, for example by physical exercise, healthy eating, reading, writing, and medication. At the beginning of the disease, the strain was felt to be negligible, but as the disease progressed most of the women's feelings of stress and frustration became more intense and they did not continue with the activities, and support was needed. COPD required major changes in their life and they always worried about the man. They felt fatigue, anxiety, and had sleep disturbances. Several women also had serious diseases of their own.

I have to get up 4–5 times every night so I am totally exhausted … I have difficulty in sleeping because I lie and listen for when he breathes, … I have had a heart attack (4)

In relation to the man

The women said they prioritized their husband's health and well-being and compromised their own health. The man's breathing problems were more important than the women's own health, and thus they ended up doing everything at home.

I do everything… at times I don't feel well, … Wash, clean and bake, I do all the shopping myself. (12)

In relation to others

Most women felt that no one in healthcare noticed their vulnerable position and risk of developing health problems. Some believed that there was no concern or empathy for them and they felt like an appendage. Others felt they were treated differently from male relatives because of their gender.

I think that healthcare is too terrible, for them, one is an appendage, consideration and empathy are missing from care. There are ethical shortfalls and one is dependent on their care, I think that men are treated better … women are seen to be more complaining. (1)

The women requested some kind of contact who could answer their questions and give them physical, emotional, and social support, especially when their spouse got worse. It would be good to talk someone such as a social welfare counsellor. The COPD school for patients and spouses was considered good, but only three couples have been offered it and participated in it, and they wished for follow-ups.

A social welfare counsellor is needed… The COPD school was extremely good, but after a few years I want a follow-up. (10)

Changes in the couple's relationship

In relation to the woman herself

The women were forced to review their life situation and reduce responsibilities for which they did not have time or energy. For example, they sold their summer cottage or caravan, or moved from a house to an apartment. Several women turned to their children or relatives to get emotional or practical support, whereas others had no one to turn to. They experienced lack of support from health professionals to discuss relationship problems caused by the disease. The total change of life situation led to many different feelings.

It is difficult to be happy and it doesn't take much to put me in a bad mood. What is needed is emotional support, one needs the help and fellowship of health professionals. (8)

In relation to the man

Some of the women conceived that they had difficulties in handling the demands from their husband. The state of the couple's relationship before the COPD had an impact on how they conceived their situation. Several couples had an open dialogue about the disease and their relationship. For some couples, the relationship deepened and for others the dialogue and relationship were affected negatively. Some of the men did not talk about their COPD or related problems, whereas others benefited from it by blaming the disease for their inability to help their wives. Some women felt exploited by their husbands. Sometimes the woman found it difficult to talk to her husband because he had become more sensitive.

One becomes aware of what one has; it has changed into a deeper relationship. (21)

He doesn't talk about illnesses… it would be better …, but it's just not possible. (16)

He never forgets the illness, he will easily talk about how ill he is. (20)

Almost all of the women felt that their husbands needed their support and found it natural to take care of them. For some women, the coughing and the mucus formation caused feelings of disgust, leading to difficulties in kissing him. For others, their feelings changed because they felt that the man had become more of a sick person. The intimate relationship changed for most women because of the COPD, as sexual intercourse was considered too strenuous for the man. Some couples had ceased to have intercourse, whereas others felt that being close was more important.

The goodnight kiss after he has coughed up a large amount of phlegm, …is horrible, I do it, but I don't like it. (3)

I don't have the same feelings; he has become a little bit like an invalid, life together isn't quite the same. (8)

In relation to others

The couple could do fewer things together, and contacts with others were reduced or broken depending on the progression of the disease. Some couples were involved in patient associations, but this also decreased gradually because of the progress of the COPD.

I can't leave him for long and go into town… I think that I would want to be involved in one thing or another but it wouldn't work. (3)

Discussion

This study is unique, as no previous study addressing conceptions of daily life in women living with a man suffering from COPD at different stages has been found. The main findings showed four different conceptions: an unchanged life situation where no support was needed; socially restricted life and changed roles; changes in health; and changes in the couple's relationship and need for support.

This study showed that women living with a man with mild COPD experienced no changes in their daily life, and therefore felt no need of support. It was when the COPD gradually escalated that the women's daily lives were affected and they conceived an increased impact on their own life situation and need of support. Many women felt that they were left alone and were not supported. The women's increased responsibilities and limited time for social activities resulted in caregiver strain, as previously shown in relatives of people with severe COPD (Seamark et al., Reference Seamark, Blake and Seamark2004; Kanervisto et al., Reference Kanervisto, Kaistila and Paavilainen2007). As in Bergs's (Reference Bergs2002) study, relatives were shown to have a reduced life situation because of the isolation. The women in the present study experienced an increased burden and difficulties in daily life; they took care of their spouse and the household, and they had to be available without the possibility of sharing the burden with someone else. The women were strongly affected by their husbands’ COPD, even if it has not reached the end stage, indicating that women lack emotional, social, and practical support, information, and cooperation. It is important that health professionals and local authorities establish contact at an early stage of the disease with those who have a chronic disease such as COPD and with their spouses, as COPD is a progressive disease.

Studies have shown a financial burden on a family when a chronic disease affects one of the family members, and that economic support from society is insufficient and leads to financial hardship (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Ryan and Connor2001; Scharlach et al., Reference Scharlach, Li and Dalvi2006). According to the present study in a Swedish context, the high-cost ceiling for medical treatment was found to cover most of the costs, but not to finance home service, which led women not to use that service.

From the patients’ perspective, a chronic disease might be seen either as an interruption of their lives, as an intrusive illness, or as an immersion in illness (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz1997). In addition, the caregiving women in this study became affected in a similar way by their spouses’ disease, and some of the women also had health problems of their own. The results showed both interruption and immersion, but mainly an intrusion of the disease – as the man's disease dominated their entire lives and led to losses. The women's day depended on the spouses’ condition; if the men had bad days, it restricted the women's daily lives. There was a role change from being a spouse to becoming a caregiver who compensated for the limitations in the man's function, which required adjustment and could affect the women's health.

The women felt they were left alone in the caring situation where their own health was at risk of deteriorating. The strain to which women were subjected was both physical and mental, and it could lead to illness, as previously described (Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Holanda, Medeiros, Mota and Pereira2007; Simpson and Rocker, Reference Simpson and Rocker2008). The women felt they were compromising their own health and putting their husband's well-being before their own. They could have serious diseases of their own, but it was the men's problems that were central and dominant. To sustain the women's health, it is crucial to encourage strategies for maintaining their own health by support from health professionals, home services, and voluntary organizations. Through a sense of coherence (SOC), the women may feel better in their caring situation. Various studies on depression, dementia, mental illness, and stroke (Andrén and Elmståhl, Reference Andrén and Elmståhl2008; Chumbler et al., Reference Chumbler, Rittman and Wu2008; Suresky et al., Reference Suresky, Zauszniewski and Bekhet2008; Välimäki et al., Reference Välimäki, Vehviläinen-Julkunen, Pietilä and Pirttilä2009) have shown the importance and influence of SOC, which is also shown in our findings on COPD.

Antonovsky (Reference Antonovsky1987) has shown that comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness lead to an SOC, and are thus essential elements if humans are to cope. Some people become ill when stressed, whereas others remain healthy, depending on low or high SOC. People's attitudes to strain are built up through resources, such as knowledge and social support. People have different resources, either in themselves or in others helping to cope with things (Antonovsky, Reference Antonovsky1987). The present study reveals that women lacked information, emotional and practical support, and that they lost social contacts and risked their own health. The caregiving women need to feel that their situation is manageable either by their own resources or with support from others (eg health professionals, municipality), or both. A sense of high degree of manageability enables a person to handle difficult situations without having to feel like a victim. It is therefore important to make the women's caregiving role comprehensible to enable them to increase the control of their daily life. The caregiving women need to feel meaningfulness so that they can confront the challenge and make the best of their situation. If health professionals show commitment to informal caregivers, they can strengthen the motivation in the women, and that creates meaningfulness. Spouses are a valuable resource for the chronically ill person (Ek and Ternestedt, Reference Ek and Ternestedt2008). Therefore, it is important to make women's caring situation comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful, and to supply the resources needed to prevent spouses from becoming tomorrow's patients.

The women called for a contact person for physical, emotional, and social support, especially when their spouse got worse. Multi-professional teamwork with coordination by a COPD nurse, familiar with the disease and continually monitoring needs and providing adequate support for caregiving women, would be helpful (Österlund Efraimsson et al., Reference Österlund Efraimsson, Hillervik and Ehrenberger2008). In Sweden, psychological/psychotherapeutic support is seldom offered to people with COPD, which means that it is rarely offered to the informal carers either (Lindqvist and Hallberg, Reference Lindqvist and Hallberg2010). The possibility of talking to health professionals with knowledge and familiarity with informal caregiving spouses’ situations has been shown to be helpful (Wackerbarth, Reference Wackerbarth1999; Salfi et al., Reference Salfi, Ploeg and Black2005). In hospitals, health professionals could develop individual care plans in which spouse planning should be integrated, irrespective of where the patient is managed, a primary healthcare clinic or a hospital.

According to the Swedish Health and Medical Services Act (1982:763), care of high quality should be person centred and holistic. To achieve these goals, contextual factors such as relatives also need to be taken into consideration and to be involved in care planning. The restriction of health care, with an increasing number of patients being cared for in their homes by relatives, creates a new and unknown situation and generates new demands on health professionals (Jegermalm, Reference Jegermalm2006). It is a challenge to plan for high-quality care, mainly home based, as a three-part cooperation between the patient, his/her family, and health professionals.

Strengths and limitations

Twenty-one interviews were conducted, which is considered an adequate number to allow different conceptions (Marton and Booth, Reference Marton and Booth2000), and this is considered a strength of the study. Findings from a qualitative study do not aim to arrive at a generalized conclusion, which can be seen as a limitation, but the results can be transferred to other settings or groups with similar characteristics (Sjöström and Dahlgren, Reference Sjöström and Dahlgren2002). Excluded were men with very severe COPD, which is the end stage of the disease, and being continuously treated with oxygen, and thus requiring more hospital treatment than being cared for at home by their spouse. No one in this study was provided with specialist care at home. The most important benefit is the deeper understanding of the studied area. The results in this study are restricted to women and men might conceive caregiving and daily life living with a woman suffering from COPD in a different way, and therefore further studies are needed.

Conclusion and implications

There is variation in women's conceptions of their daily life, related to the seriousness of the spouses’ COPD. As the COPD escalated, they increasingly felt that almost everything in their daily life was affected – in relation to themselves, the man, and others. There is a need for health professionals and local authorities to identify caregiving women's conceptions of daily life and their need for support. The contact should come in at an early stage of the disease, and with follow-ups, as COPD is progressive and the needs can change. More effort should be put into teamwork, with different professionals working together in cooperation with the patient and spouse; the COPD nurse should coordinate necessary support, and also include spouse planning from the beginning.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by the School of Health and Caring Sciences, Linnaeus University. No funding was received from any funding agency either in the commercial sector or in the not-for-profit sector. Author contributions: G.L., K.H.J., K.H.E., and B.A. were responsible for the study conception, design, and for the drafting of the manuscript. G.L. carried out the data collection and data analysis under critical revision from K.H.J., K.H.E., and B.A. G.L., K.H.J., K.H.E., and B.A. made critical revisions to the paper. K.H.J., K.H.E., and B.A. supervised the study.

Appendix 1: Interview guide

Entry question:

‘How is a typical day for you’?

Follow-up questions:

• What effect has it had on your daily life that your husband got COPD?

• How is the division of labour in your home?

• What do you do to manage your daily life?

• Do you use specific strategies to manage daily life?

• What consequences has your husband's illness had on you? Physical/mental/social/professional life?

• How is your own health?

• How do you take care of your own health?

• How is your role/relation/feelings/sex life/economy? Has it changed? If so, how?

• How are you treated by society as a spouse?

• How are you treated by health care?

• What kind of help do you need as a caregiver? Emotional support/psychological support/practical support/aid/financial support?

• What kind of support do you get from healthcare and municipality? Information? Did you get information? Are you involved and seen by health care?

• How do you conceive that the healthcare professionals perceive COPD?

• What is your opinion if I say that there may be a perception that COPD is a self-inflicted disease? If so, has it had any impact on you?

• What thoughts/feelings do you have about the past/present/future?