With the notable rise in the United States in explicitly white supremacist activities (Byman Reference Byman2022), increased political polarization (Pierson and Schickler Reference Pierson and Schickler2020), Christian nationalists’ ongoing attempts to seize power (Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020), and the emergence of a national racial reckoning (McDermott and Ferguson Reference McDermott and Ferguson2022), it is important to understand what factors contribute to political attitudes among white Americans. While political scientists, psychologists, and sociologists have focused on either socialization or political attitudes (Anoll et al. Reference Anoll2022; Burke et al. Reference Burke2013; De Mesquita Reference De Mesquita2002; Diekman and Schneider Reference Diekman and Schneider2010; Godefroidt Reference Godefroidt2022; Loyd and Gaither Reference Loyd and Gaither2018; McCall and Manza Reference McCall, Manza, Edwards, Jacobs and Shapiro2011; Peterson et al. Reference Peterson2020; Schoon et al. Reference Schoon2010; Stockemer Reference Stockemer2017; Umaña-Taylor and Hill Reference Umaña-Taylor and Hill2020), we found none that have examined the relationship of childhood ethnic-racial socialization (ERS) by parents to young adult political attitudes among white Americans, despite abundant evidence of the key role that families play in imbuing children with feelings toward various social, political, and religious experiences (Guhin et al. Reference Guhin2021) and shaping adult attitudes and behaviors (Degner and Dalege Reference Degner and Dalege2013; Grindal Reference Grindal2017; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes2006; Lesane-Brown Reference Lesane-Brown2006).

Engaging in timely research to explore this relationship is critical, especially given the increasingly enmeshed nature of political attitudes and race (Gimpel and Tam Cho Reference Gimpel and Tam Cho2004; Inwood 2020). Socialization is a factory of ideological reproduction (Feagin Reference Feagin2006) and affects how inequalities are created, maintained, and distributed. Political attitudes predict voting behaviors (Wang Reference Wang2016) subsequently affecting social inequalities (Reeves and Mackenbach Reference Reeves and Mackenbach2019). This paper examines the relations between perceived ERS in childhood and political attitudes in young adulthood among white Americans—that is, people who label themselves and their parents as “white.” We examine a national sample to capture diversity within the U.S. population of white young adults. We employ a comprehensive set of ERS measures that capture participants’ recollections of the ERS strategies their parents employed while the participant was growing up. These strategies include those historically studied in families of color and those recently identified in research with white families.

Ethnic-Racial Socialization

Socialization refers to the process of transmitting cultural norms, values, attitudes, and mores, such that the receiver is better equipped to function appropriately in a given series of roles (Grindal and Nieri Reference Grindal and Nieri2015; Guhin et al. Reference Guhin2021). While many different agents can engage in socialization, we focus here on socialization by parents. Furthermore, we focus on ERS, the process by which parents transmit ideas, attitudes, and values about race and ethnicity to their children (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes2006). The most studied dimensions of ERS are cultural socialization (messages about the family’s racial and/or ethnic traditions, such as food and holidays), preparation for bias (messages preparing children for the possibility of ethnic-racial discrimination), and promotion of mistrust (messages encouraging a skepticism of and guardedness against ethnic-racial out-groups).

Early work on ERS focused on families of color and aimed to reveal how parents used these three socialization messages to foster a positive self-concept and navigate racism in a society with inequitable opportunities (Priest et al. Reference Priest2014; Umaña-Taylor and Hill Reference Umaña-Taylor and Hill2020). In recent years, greater attention has been paid to ERS in white families (Loyd and Gaither Reference Loyd and Gaither2018; Nieri and Huft Reference Nieri and Huft2023; Simon Reference Simon2021). The research on white families generally recognizes that white families differ from families of color in that whites inhabit a socially privileged position in American society (Bowen Matthew Reference Bowen Matthew2022; Brown Reference Brown2021). Therefore, the content, patterns, and outcomes of ERS in white families may differ from those in families of color. For example, socialization about egalitarianism, which involves messages about the equality of ethnic-racial groups, in families of color may be intended to teach children of color that they are as good as white children, despite the racist messages that they receive in society (Loyd and Gaither Reference Loyd and Gaither2018; Umaña-Taylor and Hill Reference Umaña-Taylor and Hill2020). In contrast, in white families, this strategy may teach white children that people of color should not receive special treatment, even in spite of historical and ongoing inequities between people of color and whites. Similarly, mainstream socialization, which involves messages endorsing mainstream (white) institutions and values, such as individualism, and as such, deemphasizing group identities, such as race (Loyd and Gaither Reference Loyd and Gaither2018; Hecht et al. Reference Hecht2003; Rollins Reference Rollins, Roy and Rollins2019; Umaña-Taylor and Hill Reference Umaña-Taylor and Hill2020), in families of color may be intended to teach children of color how to navigate and succeed in a society structured by and for white people (Bowen Matthew Reference Bowen Matthew2022; Brown Reference Brown2021). In contrast, in white families, this strategy may operate to teach white children that mainstream white values are the only or correct values by which American society should operate.

Prior research has shown that white parents engage in less frequent and somewhat different ERS (Loyd and Gaither Reference Loyd and Gaither2018; Simon Reference Simon2021). While white parents may employ ERS strategies used by parents of color (i.e., those mentioned in earlier paragraphs), they also employ other strategies. White parents may practice silence on race, teaching that race and racism should not be discussed (Bartoli et al. Reference Bartoli2016; Briscoe Reference Briscoe2003; Pahlke et al. Reference Pahlke2020; Underhill Reference Underhill2016; Reference Underhill2018; Zucker and Patterson Reference Zucker and Patterson2018). They may promote exposure to diversity, seeking to expose their children to other ethnic-racial children and teach that diversity is valuable (Underhill Reference Underhill2016, Reference Underhill2019; Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Vittrup Reference Vittrup2018; Zucker Reference Zucker2019). Finally, they may engage in anti-racism socialization, which involves messages about types of racism (e.g., internalized, tacit, institutional, structural) other than just interpersonal racism, white privilege, standing up to racism, and allyship with people of color (Anoll et al. Reference Anoll2022; Gillen-O’Neel et al. Reference Gillen-O’Neel2021; Hagerman Reference Hagerman2017, Reference Hagerman2018; Heberle et al. Reference Heberle2021. Thomann and Suyemoto Reference Thomann and Suyemoto2018; Thomas Reference Thomas2019; Underhill and Simms Reference Underhill and Simms2022). While some other strategies (e.g., exposure to diversity) may also be motivated by parents’ anti-racist sentiments, we distinguish between those socialization strategies and anti-racism socialization that aims to teach about systemic racism.

Some white parents are relatively successful in their attempts to prevent racist attitudes, promote ethnic-racial diversity appreciation, or cultivate anti-racist attitudes in their children (Gillen-O’Neel et al. Reference Gillen-O’Neel2021; Hagerman Reference Hagerman2017, Reference Hagerman2018; Underhill and Simms Reference Underhill and Simms2022; Pahlke et al. Reference Pahlke2020; Thomas Reference Thomas2019). Others use ERS strategies that undermine their efforts and reinforce attitudes and practices that enable ethnic-racial inequities (Gillen-O’Neel et al. Reference Gillen-O’Neel2021; Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Underhill Reference Underhill2016, Reference Underhill2018; Vittrup Reference Vittrup2018; Pinsoneault Reference Pinsoneault2015). Simply, ERS among white families remains an understudied area of research, and one wrought with conflicting findings on the outcomes of ERS. This is the first of two notable gaps in the literature that we attempt to address. The second gap regards the relation of ERS to political attitudes.

ERS and Political Attitudes

Although racial attitudes inform political attitudes (Jardina Reference Jardina2021; Peterson and Riley Reference Peterson and Riley2022), we found only two studies that examine how ERS in white families relates to young adults’ political attitudes. Eveland and Nathanson (Reference Eveland and Nathanson2020) found that Republican parents, relative to Democratic parents, discussed race with their children less frequently than Democratic parents. Thompson (Reference Thompson2021) found that political party affiliation moderated the relationship between progressive ERS (messages about the structural advantages of whiteness) and awareness of structural racial disadvantages. Progressive ERS while growing up was associated with increased awareness in adulthood of the structural disadvantages faced by Blacks, and this relation was stronger for white Democrats than for white Republicans.

Prior research has linked various ERS strategies in white families to ethnic identity. Cultural socialization is linked to greater ethnic identity exploration and commitment (Else-Quest and Morse Reference Else-Quest and Morse2014; Morse Reference Morse2012; Wilson Reference Wilson2008) and ethnic identity affirmation/belonging (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes2009; Wilson Reference Wilson2008). Preparation for bias is also linked to ethnic identity, but the evidence of the specific direction of the relation is inconsistent (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes2009; Wilson Reference Wilson2008). Promotion of mistrust is linked to greater ethnic identity affirmation/belonging and exploration (Wilson Reference Wilson2008). To the extent that these forms of socialization emphasize white identity, we expect that they may also increase a sense of fear, threat, and anxiety related to whites’ group membership. Many conservative and Republican political positions are bound up in racial ideology emphasizing whiteness (Byman Reference Byman2022; Ehrenberg Reference Ehrenberg2022; Metzl Reference Metz2019; Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020). Political conservatism is motivated, in part, by perceived fear and threats (Burke et al. Reference Burke2013; Jost et al. Reference Jost2003). This is seen clearly in the current narratives circulated among political conservatives, many of which revolve around fear of immigrants, Muslims, and LGBTQ+ people, and modern public education curriculum. Therefore, we expect that:

H1: Participants who perceive more frequent cultural socialization, preparation for bias, or promotion of mistrust will be more conservative and affiliate more with the Republican party in young adulthood.

Egalitarianism, mainstream socialization, and silent racial socialization are strategies that, particularly in white families, deemphasize race and its role in enabling people to experience success in American society. For example, egalitarianism focuses on equality between ethnic-racial groups and, as such, does not teach about structural racism, which produces and maintains ethnic-racial inequities (Vittrup Reference Vittrup2018). Mainstream socialization aims to facilitate navigation of the current system rather than resistance to or modification of it (Rollins Reference Rollins, Roy and Rollins2019). Mainstream socialization focuses on seemingly individual and non-racialized ideas of success, including work ethic, good citizenship, and moral righteousness (Thornton et al. Reference Thornton1990). Of course, the propagated ideas of work, citizenship, and morality are premised on mainstream white culture. While mainstream socialization highlights the importance of ahistorical, deracialized ideas of individual success on one hand, it also deemphasizes the role of racism and discrimination affecting groups on the other (Rollins Reference Rollins, Roy and Rollins2019; Thornton et al. Reference Thornton1990). Lastly, silent racial socialization refers to strategies that actively discourage the discussion of race and the role it plays in the larger society (Keum and Ahn Reference Keum and Ahn2021).

Scholars of ERS in white families (e.g., Abaied and Perry 2021; Anoll et al. Reference Anoll2022; Bartoli et al. Reference Bartoli2016; Briscoe Reference Briscoe2003; Pahlke et al. Reference Pahlke2020; Underhill Reference Underhill2016, Reference Underhill2018; Vittrup Reference Vittrup2018; Zucker and Patterson Reference Zucker and Patterson2018) have shown how the deployment of these strategies can be reflective of colorblind or race evasive ideology, which argues that race is no longer relevant in American society and that to focus on race is to be racist (Neville et al. Reference Neville2013). Research has documented the association of this ideology with political positions against race-conscious policies, such as affirmative action (Mazzocco et al. Reference Mazzocco2012). Other research suggests that this ideology has greater resonance in conservative and Republican circles (Carr Reference Carr1997; Gutierrez Reference Gutierrez2016; Mazzocco Reference Mazzocco2017). For example, political liberals are more likely than conservatives to engage in equity-focused (rather than egalitarian-focused) decision-making (Axt et al. Reference Axt2016). Therefore, we expect that:

H2: Participants who perceive more frequent egalitarian socialization, mainstream socialization, or silent racial socialization will express more conservative political attitudes and affiliate more with the Republican party in young adulthood.

Exposure to diversity is a color-conscious socialization strategy. White parents employ it on the grounds that familiarity with ethnic-racial diversity is beneficial. For some parents, exposure to diversity is a way for children to learn about other ethnic-racial groups and be less prejudiced (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Underhill 2016; Reference Underhill2019). For other parents, exposure to diversity is a way for children to cultivate their social capital to navigate an ethnically–racially diverse society, though not necessarily to be less prejudiced (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018). Because parents with different motivations may employ this strategy (Anoll et al. Reference Anoll2022), the political attitudes that flow from exposure to this strategy may vary. We found no prior study examining the relation of this socialization strategy to political attitudes. We found only two studies examining exposure to diversity, though not as a socialization strategy, that linked greater exposure to more liberal political attitudes in adulthood (Billings et al. Reference Billings2021; Brown et al. Reference Brown2021). Given this background, we do not hypothesize a specific direction, but we expect that:

H3: Perceived exposure to diversity socialization will be related to political ideology and political party identification in young adulthood.

Like exposure to diversity, anti-racism socialization can be a color-conscious strategy. However, they differ along two dimensions. First, anti-racist socialization, as studied to date, often involves a more direct attempt to recognize systemic forces that perpetuate racism. While exposure to diversity socialization tends to be more individualistic in its underlying tenets (i.e., racism can be addressed on an individual level with greater exposure to and tolerance for different groups), anti-racist socialization often pushes for more meso- and macro-level changes. Anti-racist socialization may include creating racial justice groups in schools (Underhill and Simms Reference Underhill and Simms2022), building a critical consciousness about race (Heberle et al. Reference Heberle2021), directly confronting racism (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2017; Heberle et al. Reference Heberle2021), teaching about racial privilege (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2017; Heberle et al. Reference Heberle2021), and sheltering undocumented immigrants (Underhill and Simms Reference Underhill and Simms2022).

Second, the two strategies differ in how their benefits are framed. Exposure to diversity is often portrayed as a benefit to oneself. Middle-class white families largely expose their children to diversity to enrich their own children’s lives, not necessarily to benefit members of other ethnic-racial groups (Underhill Reference Underhill2019). In contrast, anti-racist socialization often focuses on benefiting out-group members. By identifying and challenging hegemonic whiteness, white families can better support ethnic and racial minorities (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2017). Recognizing systemic racism and striving for systemic changes, as promoted by anti-racist socialization, are likely connected to more liberal political views. While an individualistic perspective, such as that highlighted in exposure to diversity, might be found across the political spectrum, the structural critique is often linked to people on the political left. Consequently, this difference in understanding the root of racial issues might explain the political attitudes of people with exposure to different socialization strategies.

Some scholars of ERS in white families have documented the use of anti-racism socialization specifically by parents who identify as politically liberal or progressive (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2017; Underhill and Simms Reference Underhill and Simms2022) or as Democrats (Anoll et al. Reference Anoll2022). Other scholars have documented the use of this strategy by white parents but did not assess the political attitudes of the parents (Gillen-O’Neel et al. Reference Gillen-O’Neel2021; Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Thomann & Suyemoto Reference Thomann and Suyemoto2018; Thomas Reference Thomas2019; Pinsoneault Reference Pinsoneault2015). Conservatives and Republicans have been largely underrepresented and mostly inactive in the anti-racism movement, particularly in recent mobilizations associated with Black Lives Matter (Bhattacharyya et al. Reference Bhattacharyya2020; Bonnett Reference Bonnett2000; Bray Reference Bray2017; Drakulich and Denver Reference Drakulich and Denver2022; Thompson Reference Thompson2001; Zamalin Reference Zamalin2019). Because of the clear relation between political views and anti-racism, as well as the tendency to view racial issues as structural rather than individual, we expect that:

H4: Participants who perceive more frequent anti-racism socialization will express less conservative political attitudes and affiliate less with the Republican party in young adulthood.

Methods

Sample

Participants were between the ages of 18–25, which is considered to be an emerging adult (Arnett Reference Arnett2000). Consistent with much of the socialization literature (Priest et al. Reference Priest2014), we focus on young adults because they entered adulthood during a time of demographic shift toward greater racial-ethnic diversity in the United States (Frey Reference Frey2020; Robinson-Wood et al. Reference Robinson-Wood2021), which has enhanced the racial identity of white people (Jardina Reference Jardina2019). Furthermore, this age allows for participants to be good informants of culture and insightful about their own experiences, while still being able to accurately reflect on their socialization experiences while growing up. All participants identified as white, currently lived in the United States, and were raised by two white birth parents. The final sample used for this analysis consisted of 933 participants.

The average age of participants was 21.69. The sample was 53.4% female, 45.1% male, and 1.5% nonbinary or other gender. A third (30.5%) identified as a Republican, 31.1% identified as a Democrat, and 33.4% identified as an Independent or other party. Similarly, 31.6% identified as conservative, 30.7% identified as liberal, and 37.7% identified as moderate. Regarding religious beliefs, 53.5% identified as Christian, with 23.2% of Christians identifying as Evangelical. We find our sample to be comparable to the national population of white young adults in terms of age, gender, political attitudes, and religious affiliation (Pew Research Center 2020; 2017).

Procedure

We utilized Qualtrics, an online survey platform, to recruit and gather data from 1,009 participants. Participant quotas were balanced along gender and four geographic regions (West, Northeast, Midwest, South). Qualtrics maintains a panel of participants around the country; we contracted with them to access a sample. Qualtrics then gathered and screened the data and delivered an anonymized dataset to us.

Measures

We measured dimensions of ERS that have been traditionally studied in the ERS literature (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes2006) as well as dimensions identified in the literature on white families (Nieri et al. Reference Nieri2023). We measured eight total dimensions: cultural socialization, preparation for bias, promotion of mistrust, egalitarianism, mainstream socialization, silent racial socialization, exposure to diversity, and anti-racist socialization. The questions asked the respondents to retrospectively report the frequency of ERS messages and strategies they received from their parents during their youth (e.g., “When you were growing up, how often did your parents encourage you to be proud of your racial/ethnic group?”), an approach consistent with prior ERS research with young adults (Grindal, Reference Grindal2017). We focus on perceptions of parental socialization because they reveal how parenting is directly experienced (Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson2002).

Each dimension of ERS was measured with a scale containing multiple items. For each item, participants reported their perceptions of ERS from their youth with one of five response options ranging from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Very often”). The items in each scale were averaged and served as our measure for that dimension of ERS. We used empirically validated measures whenever possible, modifying them slightly to allow for comparisons across measures.

Cultural socialization consisted of five items measuring parental strategies that encourage pride for and promote a greater understanding of one’s race (e.g., “…Encourage you to attend cultural events of your racial/ethnic group”) (ɑ = .88). Preparation for bias consisted of five items measuring ways in which parents prepared their children to withstand racial discrimination (e.g., “…Speak with you about how your race/ethnicity might affect how others view your abilities?”) (ɑ = .87). Promotion of mistrust consisted of three items measuring the extent to which parents promoted an overt distrust of racial out-groups (e.g., “…Tell you to avoid other racial/ethnic groups because of their members’ prejudice against your racial/ethnic group?”) (ɑ = .91). All three measures were based on Tran and Lee’s (Reference Tran and RM2010) version of Hughes and Chen’s measures (Reference Hughes, Chen, Balter and Tamis-LeMonda1999). Egalitarianism consisted of six items exploring ways participants learned from their parents that America had equal opportunities for all races (e.g., “…Tell you that American society is fair to all races?”) (ɑ = .81) (Langrehr et al. Reference Langrehr2016). Mainstream socialization consisted of four items measuring how parents minimized the importance of race in favor of other individual traits (e.g., “…Tell you that a person’s individual characteristics are more important than the characteristics of the group(s) to which they belong?”) (ɑ = .76). This was created by the researchers based on the work by Rollins (Reference Rollins, Roy and Rollins2019). Silent racial socialization consisted of five items measuring how parents discouraged discussions about race (e.g., “…Tell you to avoid talking about race with other people?”) (ɑ = .89) (Keum and Ahn Reference Keum and Ahn2021). Exposure to diversity consisted of four items measuring how parents fostered interracial relationships (e.g., “…Encourage you to be friends with people from other racial/ethnic groups.”) (ɑ = .87). Anti-racism consisted of three items measuring how parents directly acknowledged and addressed the negative impacts of racism (e.g., “…Speak with you about famous racial incidents like the Ferguson riots.”) These two measures were created based on qualitative research on whites’ socialization (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Pahlke et al. Reference Pahlke2020; Underhill Reference Underhill2019; Vittrup Reference Vittrup2018). Please see Appendix A in the supplementary material for the items within each ERS measure.

Political attitudes were measured using two questions. Political ideology was measured by asking, “What best describes your current political attitudes?” Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly liberal” to “Strongly conservative.” Political party affiliation was measured by asking, “What best describes your current political party affiliation?” Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Democrat” to “Strongly Republican,” with an eighth answer for “Other political party” available. Cases reporting “Other party” were excluded. Both questions are based on similar measures in the General Social Survey (Smith et al. 2019), which measures political ideology and political party identification along a bipolar 7-point Likert scale.

Rather than creating an index variable combining conservative attitudes and Republican party affiliation, we examined the variables separately. While there is a strong correlation between political attitudes and party affiliation, some individuals may disaffiliate with the party most closely aligned with their political attitudes (Pew Research Center 2021). Additionally, some may choose to affiliate with a party to mobilize voting power while not fully endorsing the political party’s platform. For these reasons, we pursued a more nuanced assessment of political attitudes, analyzing political ideology separately from political party affiliation.

Covariates included gender, education level, religious affiliation, and identification as an Evangelical Christian, which previous research indicates tend to be related to political attitudes (Collet and Lizardo Reference Collet and Lizardo2009; Diekman and Schneider Reference Diekman and Schneider2010; Hayes Reference Hayes1995). Gender was measured using one question (i.e., “What is your gender?”), with the available options being “Man,” “Woman,” and “Nonbinary or other gender.” Man was the reference category. Education level was asked with the question, “What best describes your highest level of education,” with options ranging from “less than 8th grade” up to “master’s degree or higher degree.” Religious affiliation was captured by the question, “What best describes your religious affiliation (if any)?” Consistent with existing religiosity measures, participants could choose “Protestant,” “Catholic,” “Other Christian,” “Jewish,” “Atheist,” “Agnostic,” and “Other affiliation.” During data analysis, “Jewish” and “Other affiliation” were collapsed into a single “Non-Christian” category, and “Atheist” and “Agnostic” were collapsed into “Secular.” Protestant was used as the reference category during analyses. Participants identified as being Evangelical or not (i.e., “Do you identify as an Evangelical Christian?”), answering, “Yes” or “No.” The latter was the reference category. Preliminary models also explored age and region of residence as covariates. However, they were not related to the outcomes and, thus, were not included in subsequent analyses in the interest of parsimony.

Analyses

We produced descriptive statistics on all measures (Table 1) and bivariate correlations of ERS variables, political attitudes, and covariates (Table 2). We then conducted two ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions (Table 3). The regression models examined the direct relation of each type of perceived ERS to each of the two outcomes, including all ERS strategies and controlling for covariates (religious affiliation, Evangelical identification, gender, and highest level of education). We report standardized regression coefficients.

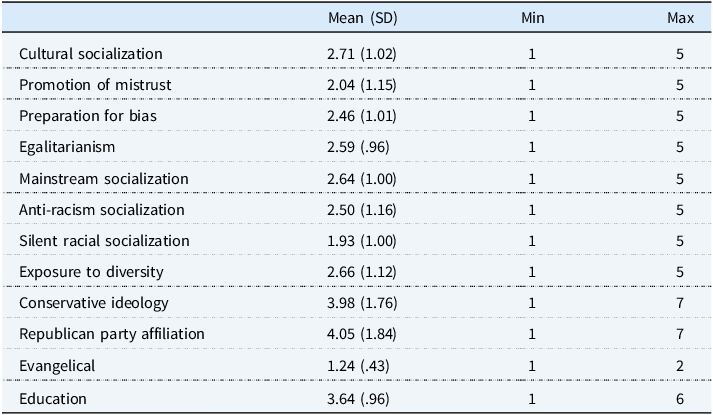

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of perceived ethnic-racial socialization and participant characteristics

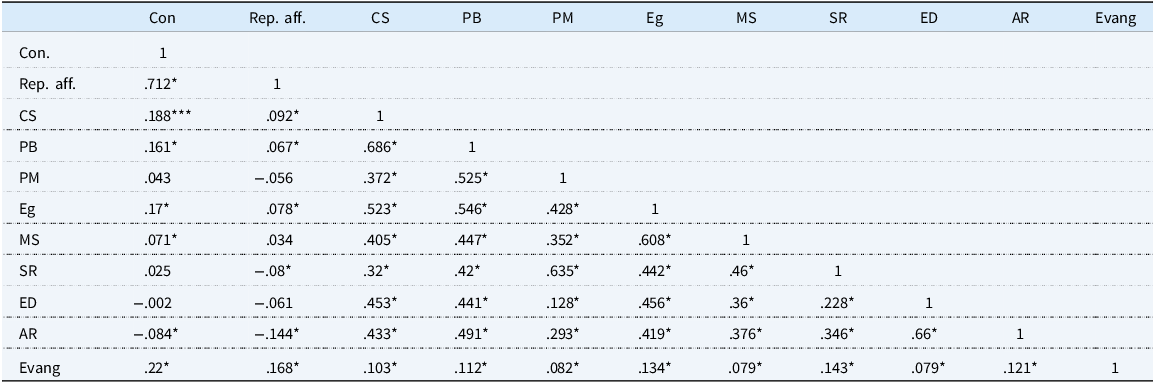

Table 2. Correlations between perceived ethnic-racial socialization and political attitudes

*p < .05.

Con. = conservative ideology, Rep aff. = Republican affiliation, CS = cultural socialization, PB = prep for bias, PM = promotion of mistrust, Eg = egalitarian socialization, MS = mainstream socialization, SR = silent racial socialization, ED = exposure to diversity, AR = anti-racism, Evang = evangelical.

Table 3. Ordinary least squares regressions of perceived ERS on political attitudes (standardized coefficients)

+ p < .10 *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Results

On average, the frequency of ERS strategies participants reported experiencing is low (Table 1). Participants report having experienced silent racial socialization least frequently and cultural socialization most frequently. On average, participants experienced all ERS strategies rarely. Participants leaned slightly conservative and slightly Republican. The Pearson correlations of all ERS strategies among themselves are positive and statistically significant (Table 2).

We find that most childhood ERS strategies relate to young adult political attitudes. We find partial support for Hypotheses 1. Cultural socialization was positively related to conservatism (β = .124, p < .01), and the relation to Republican party affiliation trended toward but did not reach statistical significance (β = .074, p < .10). Preparation for bias was positively related to both conservatism (β = .112, p < .05) and Republican party identification (β = .11, p < .05), implying a more direct connection between this form of ERS and both ideological and partisan alignment. Promotion of mistrust was not associated with conservatism but was inversely associated with Republican party affiliation (β = −.091, p < .05). These divergent results raise questions about how different components of ERS align or misalign with political ideology and partisanship, suggesting that some forms of ERS might reinforce ideological beliefs without directly influencing party affiliation. Broadly, they suggest that cultural socialization may be more strongly connected to conservative ideology than to Republican affiliation. Conversely, the promotion of mistrust appears more strongly related to Republican affiliation than conservative ideology. Preparation for bias is equally related to both.

With regard to Hypothesis 2, we find partial support. Egalitarianism was positively related to conservatism (β = .147, p < .001) and Republican party affiliation (β = .097, p < .05). This indicates that egalitarian socialization, despite its ostensibly neutral stance, may subtly encourage conservative leanings. Mainstream socialization was not associated with conservatism or Republican party affiliation. Silent racial socialization was not associated with conservatism but was inversely associated with Republican party identification (β = −.115, p < .01). This complex pattern suggests that colorblind approaches to ERS can have diverse and sometimes counterintuitive effects on political attitudes and affiliation. Broadly, this suggests that silent racial socialization is related more strongly to Republican party affiliation than to conservative ideology. Overall, among these three approaches, we find that egalitarianism and silent racial socialization are linked to conservative attitudes (though in opposite directions).

We do not find support for Hypothesis 3. Exposure to diversity is not related to conservative ideology or Republican party affiliation. This finding could indicate that exposure to diversity is either a more neutral or complex factor in shaping political attitudes. Consistent with Hypothesis 4, anti-racism is negatively related to conservative ideology (β = −.165, p < .001) and Republican party affiliation (β = −.157, p < .001). This finding highlights the strong relation of anti-racism socialization to liberalism and Democratic affiliation.

The OLS models (Table 3) indicate that ERS strategies and the covariates explain 25% of the variance in political attitudes and 21% of the variance in Republican party affiliation. Finally, in a post hoc analysis to explore multicollinearity, we examined variance inflation factors (VIF) after running OLS regressions and found no collinearity using a cutoff score of 3.5. The VIF scores ranged from 1.06 to 3.32, well below a level of concern warranted for removing variables from the models. This cutoff is consistent with the literature, which often utilizes a cutoff score of 3.5, 5, or 10 (Craney and Surles Reference Craney and Surles2002; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2007).

Discussion

Using a large national sample, we employed a comprehensive set of measures of perceived ERS to explore the relation between ERS strategies within white families and young adults’ political attitudes. We find full or partial support for three of our four hypotheses. Consistent with multiple bodies of literature identifying the links between race and politics as well as socialization and adult attitudes (Degner and Dalege Reference Degner and Dalege2013; Emerson and Smith Reference Emerson and Smith2000; Eveland and Nathanson Reference Eveland and Nathanson2020; Froese and Mencken Reference Froese and Mencken2009; Green and Dionne Reference Green, Dionne and Teixeira2008; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes2006; Lesane-Brown Reference Lesane-Brown2006; Thompson Reference Thompson2021; Tranby and Hartmann Reference Tranby and Hartmann2008), we find that multiple ERS strategies relate to white young adult political attitudes. More specifically, we find that many ERS strategies are strongly related to political ideology and party identification and more so than demographic predictors (e.g., religious affiliation, education level, gender).

Cultural Socialization, Preparation for Bias, and Promotion of Mistrust

We find that cultural socialization is related to more politically conservative views, and preparation for bias is related to both conservatism and Republican party affiliation. Cultural socialization and preparation for bias are socialization strategies that emphasize ethnic-racial identity, and the salience of white identity may make white young adults more receptive to conservative and Republican platforms that emphasize the need to be concerned about and protect one’s position in society, particularly as told through white victimization narratives (Jost et al. Reference Jost2003; Phipps Reference Phipps2021; Boehme and Isom Scott Reference Boehme and Isom Scott2020; Sengul Reference Sengul2022).

The finding that cultural socialization is more strongly related to conservative ideology than Republican party affiliation is interesting. It may be that exposure to cultural socialization in childhood was more common among those who identify as conservative than those who identify as Republican. For example, it may be that children who were taught racial/ethnic traditions and customs, important people in the history of racial/ethnic groups, and pride in their racial/ethnic group appreciate, as young adults, conservative ideology’s high value on tradition and heritage. Conservatives’ emotional investment (and subsequent fury upon removal) of Confederate monuments, flags, and symbology is a prime example of this (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper2021; Cooper and Knots Reference Cooper and Knots2006). While the Republican party may also value tradition and heritage, it must necessarily focus on the present and future in addition to the past, given electoral politics. As a result, cultural socialization may not as clearly relate to party affiliation.

The finding that preparation for bias was related to conservative attitudes and Republican party identification is not surprising, given the strong relation between conservative views and Republican party identification. While conservative ideology often includes broader values, such as fiscal responsibility and individual liberty, the Republican party has recently relied heavily on narratives of white victimization in much of their campaigning. This includes messages around in-group protection, national identity, and skepticism toward out-groups. The rise in alt-right and alt-lite political figures (Trump, Marjorie Taylor Green, Lauren Boebert, Alex Jones) and organizations (Three Percenters, Proud Boys, Oath Keepers) has been predicated, in part, on framing white Americans as systematically disenfranchised, marginalized, and victimized (Boehme and Isom Scott Reference Boehme and Isom Scott2020; Sengul Reference Sengul2022).

Although promotion of mistrust also emphasizes ethnic-racial identity, it was not related to political attitudes as hypothesized. Promotion of mistrust and anti-racism socialization are positively correlated. For participants who received both of these strategies, they may conclude that avoiding interaction with other groups, as encouraged by promotion of mistrust messages, is a way to respect others (and the social spaces they occupy). Thus, avoiding interaction with another ethnic-racial group may be interpreted as avoiding performing racism (i.e., avoidance is anti-racist). If this is true, an outcome of this would be that socialization through promotion of mistrust may not breed fear, as it provides a way to avoid racism. Mistrust is particularly fear-inspiring if one is also not equipped with tools to address mistrust. However, if individuals are delivered or perceive a two-pronged message—mistrust other groups and avoid them as a way to avoid performing racism—then they may feel less fearful or anxious. In turn, a person who receives this two-pronged socialization may find less reason to affiliate with the Republican party in young adulthood, as fear is a motivator of conservative attitudes and Republican party affiliation (Burke et al. Reference Burke2013; Jost et al. Reference Jost2003). This fear, however, may not directly translate into having more conservative views, as conservatism often includes broader ideologies unrelated to fear.

Egalitarianism, Mainstream Socialization, and Silent Racial Socialization

Although we hypothesized that exposure to egalitarianism, mainstream socialization, and silent racial socialization would be positively associated with political attitudes, the results were mixed. We anticipated that the colorblind nature of these socialization strategies would lead young adults to respond favorably to conservative and Republican platforms that reflect colorblind ideology (Carr Reference Carr1997; Gutierrez Reference Gutierrez2016; Mazzocco Reference Mazzocco2017). We do find egalitarianism socialization—which promotes the idea that all individuals in the United States, regardless of race, have equal opportunities—is positively related to conservative ideology and Republican party affiliation.

Regarding mainstream socialization, we find there is no clear relation to political outcomes. Some of the items in this measure captured messages minimizing racial differences. People who received these messages from parents may be less willing to endorse white victimization narratives, which highlight racial differences—at least at the group level, and, thus, be less likely in young adulthood to endorse conservative ideology and the Republican party. This complicated result highlights the need to better capture the nuance in socialization messages. Some messages convey equality among individuals, while others convey equality among groups. Some messages affirm the existence of racial differences due to interpersonal racism, while others affirm the existence of racial differences due to systemic racism. Some focus on the status of people of color, while others focus on the status of whites. Our measure of mainstream socialization may tap better into liberal colorblind ideology, emphasizing people of color as victims of interpersonal racism, than into conservative colorblind ideology, emphasizing whites as victims of systemic racism.

Regarding silent racial socialization, which involves messages minimizing discussion of and attention to race, we find it not to be related to conservative ideology and, unexpectedly, negatively related to Republican party affiliation. As with promotion of mistrust, silent racial socialization was positively correlated with anti-racism socialization. It may be that those who receive these messages together interpret them to mean that not talking about race is a good way to avoid being racist. Studies have shown that some white parents, including some politically liberal parents, believe avoidance of race talk will prevent their child from becoming racist (Briscoe Reference Briscoe2003; Pahlke et al. Reference Pahlke2020; Underhill Reference Underhill2016, Reference Underhill2018). Young adults who were socialized in this way may be less likely to affiliate with the Republican party. Meanwhile, it may be that Republican young adults had parents who explicitly spoke with them about race, including about the potential victimization of whites as a group. In such families, the children would be more likely to affiliate with the Republican party in young adulthood since the party claims to defend against a supposed threat to whites (Boehme and Isom Scott Reference Boehme and Isom Scott2020; Jost et al. Reference Jost2003; Phipps Reference Phipps2021; Sengul Reference Sengul2022). These beliefs about threats to whiteness may not be closely connected to the conservative ideology though. Thus, the relation between silent racial socialization and conservative ideology may be weaker than that between silent racial socialization and party affiliation.

With all three of these strategies, we note that while colorblind ideology is a strong feature of conservative ideology and Republican doctrine, as previously described, research has shown that whites across the political spectrum may endorse colorblind ideology (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2017), and furthermore, white parents wanting to socialize their children to be anti-racist may employ strategies that reflect their own endorsement of colorblind ideology (Hagerman Reference Hagerman2018; Pahlke et al. Reference Pahlke2012; Vittrup Reference Vittrup2018; Zucker and Patterson Reference Zucker and Patterson2018; Zucker Reference Zucker2019; Pinsoneault Reference Pinsoneault2015). Going forward, therefore, it is important to attend to differences in silent racial socialization messages: some minimize ethnicity–race with the goal of preventing racism, and others minimize it because the belief is that racism does not exist or race is not salient to white people. While both messages are problematic in that they minimize race, they may inform future political attitudes in opposing ways. Researchers should explore silent racial socialization, not just by assessing the frequency of messaging but also the content and intent of messaging, which may help clarify how and why parents talk about whiteness.

Exposure to Diversity

While we did not predict the direction of the relation, we expected to find a statistically significant relation between exposure to diversity and political attitudes. However, we did not find exposure to diversity to be associated with political attitudes. It may be that this effect is contingent on the reasons why parents employ these strategies and the specific content of these messages that underlie the parents’ rationale. For instance, if parents contextualize exposure to diversity strategies within a broader discussion of racial injustice, this might yield a stronger relationship with liberal ideology and party identification. In our analyses, since we did not identify parental intent in exposure to diversity strategies, these unmeasured countervailing effects may have washed out in the models. As with silent racial socialization, then, it will be important in future research to better capture the intent of messages about exposure to diversity and whether they involve acknowledging the existence and injustice of racism. Gathering data about parents’ ERS goals (e.g., children’s attitudinal, behavioral, or affective change) can help provide clarity.

Anti-racism Socialization

We find that, as expected, anti-racism socialization is negatively related to conservative ideology and Republican party affiliation. This result is consistent with findings from the Pew Research Center (2020) that white Democrats in 2020 were more likely to acknowledge structural racism than other whites. It is also consistent with historical precedence that anti-racist projects were more commonly engaged in by liberals than conservatives (see Black Panthers, Black Lives Matter, By Any Means Necessary, Showing Up for Racial Justice, Anti-Racist Action Network (Alkebulan Reference Alkebulan2007; Clay et al. Reference Clay2023; Crass Reference Crass2013; Cullors Reference Cullors2018; Moore and Tracy Reference Moore and Tracy2020)).

Our findings on anti-racism socialization also illustrate complicated messaging in white families. Anti-racism socialization is highly correlated with the promotion of mistrust, indicating that the two may be delivered together. The fact that these seemingly opposing messages are being communicated within the same family seems to indicate a larger pattern with white parents—they mean well but may not be succeeding at the anti-racism in which they believe themselves to be engaging. This possibility is consistent with the literature suggesting white parents who engage in anti-racist socialization struggle with various tensions and conflicts (Heberle et al. Reference Heberle2021). Some white parents, whether liberal or conservative, appear to have good intentions (i.e., developing an anti-racist political consciousness in their children), but their goal is complicated by the promotion of mistrust messaging.

Further investigation is needed to better uncover the content, quality, and intent of anti-racist messaging in particular. We need to expand the quantitative measurement of anti-racism socialization to capture the various messages parents may share—for example, about how to be an ally and how to divest from white privilege. Furthermore, whether quantitatively or qualitatively, we need to explore the extent to which parents’ anti-racism messaging includes or co-occurs with talk of specific political issues, political parties, or politicians. It could also be helpful to assess whether and how parents’ tensions and conflicts associated with anti-racism socialization relate to children’s experience and processing of that socialization, potentially moderating its relation to political attitudes. It could also be helpful to model together parents’ ERS goals and strategies to assess for alignment and its impact. It is not clear, for example, if white liberal and conservative parents have the same intent behind their anti-racist socialization messages. However, suppose it is true that both liberals and conservatives alike want a less racist, non-racist, or anti-racist future. In that case, we need to explore how racial attitudes are socialized within the home and how those attitudes may differ across the political spectrum. This is crucial, as anti-racist messaging is a primary site of racial attitude creation, replication, and subversion.

In summary, these findings reveal that childhood ERS is related to young adult political attitudes but in nuanced and varied ways. The distinct patterns observed for each ERS strategy demand from future researchers a deeper exploration of how these socialization practices relate to the development of political beliefs and identities.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations of note are the cross-sectional and retrospective nature of the data. There may be inaccuracies in participants’ memories when asked to reflect on childhood experiences. Additionally, given the data being collected at a single point in time, it is impossible to identify causal relations. While our strength lies in the comprehensive measurement of the types of perceived socialization by parents, we did not collect information from other socializing agents (e.g., religious institution, peers, school, media). Another limitation is that we combined race and ethnicity; we did not tease apart a white racial identity from a white ethnic identity.

Future research could collect longitudinal and prospective data to explore causal relations in ERS strategies and political attitudes. Additionally, future research could explore other socializing agents and their role in the processing of parental socialization messages. We suggest refinement of the quantitative measures of ERS, particularly those for egalitarianism, mainstream socialization, silent racial socialization, and exposure to diversity to better capture the nuances of the messages in white families across the political spectrum. Additionally, future researchers could examine how parental political ideology influences the selection of ERS strategies they utilize with their children. Finally, we suggest employing qualitative methods to explore how different ERS strategies contribute to young adult political attitudes. Specifically, we suggest in-depth interviews with young white adults to better ascertain the meanings they ascribe to various ERS strategies they experienced growing up, as well as their perceptions on the relations between ERS strategies and political attitudes.

The ERS strategies we are seeing in white families are clearly complicated. It is certainly not as simple as labeling one portion of the political spectrum more or less racist. Moving forward, we urge researchers to explore the content and intent of ERS messaging. Further, we recognize that racial attitudes have real political implications. Because attitudes translate to positions on policy matters, we note the need to explore perspectives on other specific social and political matters (e.g., voting rights, affirmative action policies, immigration attitudes, far-right support).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2024.4.

Funding statement

The data collection was supported by a grant from the CLASS Excellence Fund from the University of Idaho. The analysis was supported by a grant from the Academic Senate, University of California at Riverside.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.