In Ghana, maternal and child undernutrition remains a major public health challenge and Ghana has been classified among the thirty-six countries global accounting for 90 % of all stunting among children under 5 years(Reference Bhutta, Ahmed and Black1,2) . According to the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, about 20 % of children under 5 years were stunted(2). In 2018, the prevalence rates of stunting were 37, 36, and 25 % for the Northern, Upper East and Upper West regions, respectively, while the prevalence rates of wasting were 11, 11, and 7 % in the same regions(Reference Sienso and Lyford3). Among children under 5 years, 66 % were anaemic, while 44 % of women 15–49 years of age were anaemic(2). Additionally, 41 % of women nationally are now recorded as overweight and obese, suggesting a growing double burden of malnutrition. Urban Ghanaian women are increasingly becoming overweight and obese, while women in rural areas remain underweight(Reference Doku and Neupane4). In 2010, about 1·2 million people in the general population in Ghana were food insecure with a greater proportion of this group coming from the Northern part of the country(5). Low productivity in the agriculture sector as a result of low soil fertility and unreliable rainfall has been a major problem for food and nutrition security in Ghana(5).

Ghana’s National Nutrition Policy aims to increase the coverage of high-impact nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific interventions to ensure optimal nutrition of Ghanaians, with special reference to improving maternal and child nutrition(6). The policy is intended to educate people about the importance of investing in nutrition, guide the implementation of evidence-based nutrition interventions and promote healthy lifestyles and appropriate dietary habits(6). Various interventions, such as postharvest food storage techniques and production of animal-sourced foods, have been introduced to increase and improve access to nutritious foods in sub-Saharan African countries including Ghana(Reference Masters, Rosettie and Kranz7,8). Integrated agriculture–nutrition interventions in Ghana have resulted in significantly higher child length and height z scores, improved diet diversity and quality of infant feeding practices, some of these linked to women growing empowerment(Reference Marquis, Colecraft and Kanlisi9,Reference Malapit and Quisumbing10) . Also, growth promotion, micronutrient supplementation, behaviour change communication about infant and young child feeding practices and community management of severe acute malnutrition have also been introduced to improve nutritional status(Reference Gongwer and Aryeetey11).

However, access to nutritious foods remains a challenge in Ghana where factors including diseases and pests affect crop yields and flooding and poverty affect availability of and access to nutritious foods(Reference Zakari, Ying and Song12). Climate change exacerbates problems of access to food in Ghana. It disrupts agricultural outputs, especially in the Northern region of Ghana which is particularly vulnerable to climate change, and where millions of poor smallholder farmers rely on rainfall for food and income for their families(Reference Etwire, Al-Hassan and Kuwornu13,Reference Antwi-Agyei, Fraser and Dougill14) .

Despite efforts, maternal and child undernutrition still remains a challenge in Ghana(Reference Sienso and Lyford3,Reference Tette, Sifah and Nartey15) . There is limited evidence to guide appropriate community-level initiatives to address nutritional challenges in developing countries such as Ghana. Designing interventions to improve nutrition requires a clear understanding of the personal and contextual factors affecting patterns of food choice and consumption, including social and psychological factors(Reference Robinson16,Reference Naidu, Baliga and Yadav17) . The current study explored community perceptions on contextual strategies to improve maternal and child nutrition in rural Kassena-Nankana Districts of Northern Ghana.

This is a sub-study of a larger National Institute for Health Research-funded international collaboration Improved Nutrition Preconception Pregnancy Post-Delivery of partners based in Ghana, Burkina Faso, South Africa and the UK. Improved Nutrition Preconception Pregnancy Post-Delivery aims to develop supportive delivery of nutrition interventions in the ‘first 1000 days plus’, meaning preconception, pregnancy and the first 2 years of life. The community’s perceptions of such interventions are presented in this special series(Reference Compaoré, Ouedraogo and Boua18–Reference Watson, Kehoe and Erzse20). These were collected to inform the design of interventions to improve maternal and child health and nutrition in these populations.

Methods

Study design

This qualitative study draws on data from ten focus group discussions (FGD) with community-dwelling adult men and women aged 18–50 years. The discussions were conducted between January and April 2019. Qualitative research is descriptive of the process and the meanings gained through words(Reference Creswell21), which helps in capturing the feelings, experiences and perceptions of individuals on the issue under investigation. The approach was deemed appropriate because our study aimed to gain a deeper understanding of local people perceptions of contextual solutions to improve maternal and child nutrition.

Study site

The study was conducted in the Kassena-Nankana East and West Districts of Northern Ghana by the Navrongo Health Research Centre. The Navrongo Health Research Centre operates the Navrongo Health and Demographic Surveillance System in the two districts. The districts cover an area of 1675 km2 of Sahelian savannah with a population of about 153 000(Reference Oduro, Wak and Azongo22). The main languages spoken in the area are Kasem and Nankani. The population is predominantly rural with subsistence farming as the mainstay of the economy. There are two distinct seasons: the rainy season from May to October and the dry season from November to April. The population largely lives on subsistence crops including millet, sorghum, rice, maize and groundnuts(Reference Chatio and Akweongo23). Fruits and vegetables such as tomatoes, onions, pepper, sweet potatoes, cabbage and lettuce are also produced in the area. Inhabitants of the two districts mostly live in multi-household compounds.

Sampling techniques

Data from the Navrongo Health and Demographic Surveillance System were used as the sampling frame. For data collection purposes, the Navrongo Health and Demographic Surveillance System area has been divided into five zones (East, West, North, South and Central)(Reference Chatio, Aborigo and Adongo24). The East and South zones are predominantly Nankani speaking while the West, Central and North are Kasem speaking zones. These zones are further divided into clusters. Two zones, one each in the Kasem (North) and Nankani (South) speaking areas, were randomly selected for the study. Ten clusters (five in each zone) were randomly selected as communities where the FGD were conducted. In each cluster, about twenty individuals who met the age and sex criteria were randomly selected and were contacted by the data collectors. The first twelve people who gave consent were invited to participate in each FGD.

Training and data collection procedures

Four university graduates (research officers) with experience in conducting qualitative interviews were recruited and trained for data collection. A pre-test was conducted at the end of the training to evaluate the performance of data collectors and help finalise the discussion guides for data collection.

Each FGD was conducted by two research officers, one serving as a moderator and the other as an observer and a note taker. The data collectors visited individuals at home and invited them to participate in the FGD. The FGD were constituted separately based on gender (men, women), ethno-linguistics group (Kasem and Nankani) and further disaggregated by age (18–25, 26–39 and 40–50 years for women; 24–34 and 35–50 years for men). This enabled us to solicit views across different age–gender groups among the two main ethnic groups in the study area. A total of ten FGD (four with men and six with women) were conducted. A suitable venue was selected by study participants at the community level where the discussions were held using the two main local languages (Kasem and Nankani) and tape recorded with the consent of study participants. On average, the FGD lasted 1 h. A harmonised discussion guide was developed for all three study sites with enough flexibility to allow researchers to tailor the discussion to the local context. The guide covered areas such as maternal and child health issues, maternal and child nutritional problems and suggestions to improve maternal and child nutrition.

Data analysis techniques

The recordings were transcribed verbatim into English by graduate research officers who were native speakers with experience in transcribing qualitative interviews. A codebook was developed using the original research questions and themes that emerged from the data to guide data coding and analysis. The data were organised using QSR Nvivo 12 software for thematic analysis(Reference Guest, Macqueen and Namey25). The transcripts were initially coded independently by two members of the research team. The coding process involved a critical review of each transcript to identify emerging themes from the data and also based on the objectives of the study. The two coders then met to compare their independently identified themes. They resolved any divergence by re-reading the relevant sections of the transcripts together and agreed on the best fit interpretation of the data. The findings are presented in themes and supported by relevant quotes from the data.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

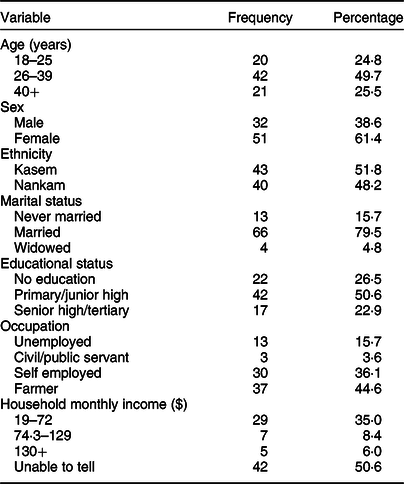

Eighty-three adults took part in the study, of whom 49·7 % were between 26 and 39 years. The majority of the participants were married and 51·8 % were from the Kasem ethnic group. About 51·0 % had between primary and junior high education with only 22·9 % having secondary or higher qualification. About 45·0 % of the participants were farmers. Almost 51·0 % were unable to indicate their household monthly income because they did not know how much they earned (Table 1).

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

Community perspectives of factors affecting maternal and child nutrition

Study participants highlighted four main factors affecting maternal and child nutrition in the area. These comprised poverty, poor harvest, lack of irrigated agricultural land and perceived lack of support from men.

Poverty

Poverty was perceived to be a significant determinant of participants’ nutrition across all ages and genders. Most participants believed poverty to be the main economic determinant limiting their access to nutritious food. They attributed this to the high rates of unemployment in the area. Study participants associated the paucity of job opportunities with lack of money to buy the food that would enhance their nutritional status.

The hand is less (meaning there is no money). To be honest, in this our community, money is a problem for us. There is no work for us to do to get money and support ourselves. It is only sufferings and hunger because when we need something we cannot buy because of poverty. (FGD-women-Kasem-18–25 years)

We know nutritious food helps the woman…but it is poverty that makes you unable to take care of the woman or buy nutritious food she needs to eat to help her and the children … (FGD-men-Nankani-35–50 years)

Poor harvest and lack of irrigated agriculture

Another challenge to good nutrition identified by study participants was poor harvest due to low soil fertility and unreliable rainfall. Both men and women in the discussions held the view that food production in the district was dictated by weather and often limited to the rainy season, which is short and unreliable. Study participants noted that farm harvests were affected by low soil fertility and diseases and pests that affect crop yields resulting in poor nutrition at the community level.

Our land is not good (infertile). We all farm but we don’t get anything because there is no fertilizer. When it is raining season, we farm everywhere and we don’t get returns on the farming because we don’t have money to buy the medicine (pesticides) to spray and kill the diseases affecting our crops. (FGD-men-Kasem-35–50 years)

As for farming, there is nothing in there. You will work and work but you would not get anything there, the little you get from the farming you eat that. Within a short time, the food is finished…where will you get food to eat and be healthy? It is only sufferings. (FGD-women-Nankani-18–25 years)

The majority of the study participants were of the view that unavailability of water in the dry season made it difficult to grow vegetables and other food crops, thus restricting access to nutritious food in the community. They explained that vegetables were easily available during the rainy season, making it easier to enrich their diet, but this was not the case in the dry season.

….When it is raining season, we do gardening, but this dry season, there is no water for us to do the gardens or grow crops to get food during this time of the year. So as we are sitting, it is difficult for us to get nutritious food this time of the year. (FGD-men-Kasem-24–34 years)

Perceived lack of male support

Study participants also shared their views on how gender roles affect maternal and child nutrition in the area. Most of the women perceived that men were not taking up their responsibilities of providing for the family. They recounted the difficulties they faced in the upbringing of their children, noting that the children’s education, health needs and feeding were left under their care without support from their husbands. Study participants of both genders identified the lack of support by men as a significant barrier to access to nutritious foods by women and children as shown in the excerpts below:

To me, it is the drinking. The men, they married us and we are now suffering. They have money to buy alcohol and they know what to do outside and they have left the women. The problem is that they have refused to care for the children and now we (women) don’t have anything to do and get money. How can we get nutritious food for the children? That is the problem we have in this community. (FGD-women-Nankani-26–39 years)

That is true, most men as soon as they get the money, they forget that they have women that they have to take care of let alone say children. Where will they (women and children) go and get food to eat if you the man is not concerned? So that is the problem for some of the men here. (FGD-men-Nankani-24–34 years)

Although the women did not directly suggest ways in which men could be more involved in family life, the men reflected on how they could support women, suggesting that they should be more patient and contribute to childcare.

Having patience, allow your temper to go down… you should know how to talk kindly to a pregnant woman. (FGD-men-Kasem-35–50 years)

The men too should have patience to bath the children, when they are sick. Give them their medications before they go out. (FGD-men-Kasem-35–50 years)

Proposed contextual interventions to improve community nutrition

Study participants identified various strategies that could improve maternal and child nutrition in the area. These included irrigated agricultural land, education on nutrition, provision of agricultural inputs and food supplements.

Irrigated agricultural land

A common suggestion among study participants was for a construction of dams in the communities to provide water for all year round agricultural activities. This would help community members to rear animals during the dry season and also make small gardens where they could grow nutritious foods and fresh vegetables to facilitate access to nutritious food for their families.

What I have to say is that if we are provided with water like dams for us to do gardens, we can get fresh vegetables to eat during the dry season. This will be beneficial to us because it will help us get food. (FGD-woemn-Nankani-18–25 years)

….So, if we had water, we can get all the vegetables we need to eat and be healthy. With the water, we can grow trees, vegetables and when that happens, food will not be a problem for us in the community. I think that water can help us to do dry season gardens to enable us take care of our women and children. (FGD-men-Kasem-35–50 years)

Provision of agricultural materials

Some of the participants associated their poor farm yields with lack of agricultural materials. According to them, lack of these farming materials leads to poor yield. Participants were of the view that any support in terms of high yield seeds (groundnuts and beans) and also fertiliser and pesticides to spray insects that destroy their crops would improve their farm yields and thereby provide enough nutritious food for the community.

Most of us don’t have….So if we could get support in terms of some of the seedlings it will help us to have good harvest. (FGD-women-Kasem-40–50 years)

….Here, when you plant your crops and before you realize insects will eat everything. So I think if they are able to come and support us with chemicals (pesticides) and fertilizer at a reduced price that will enable us get good yield and there will be food for us to eat. (FGD-men-Nankani-35–50 years)

Some participants also wished for financial support to rear animals such as goats, sheep and fowls. They believed that meat from such animals could enrich the nutrition of their households. Moreover, they could sell some of the animals to buy other nutritious food that they did not produce to enhance their nutritional status.

What I want to be done here to help us especially the women is that if they could get support especially, financial support to rear goats and fowls, it will benefit us a lot. (FGD-women-Nankani-40–50 years)

If the youth could be supported to rear animals that would help the women in terms of their diet….we could extract milk from cattle for the women to be drinking and for feeding the children. So if you could support us in rearing animals, it would help us. (FGD-men-Kasem-24–34 years)

Effective community education on nutrition

Study participants recommended that intensive education be provided to community members, especially women, on the types of locally produced nutritious foods they could eat and more importantly how to prepare them. To facilitate this approach, participants suggested that trained community-based health volunteers could educate people in the communities on nutrition issues. This strategy was identified mainly by the men in the discussions as a way of improving community members’ knowledge on nutrition and thereby contributing to enhance maternal and child nutritional status.

You see, now we don’t have people to talk to us especially women about the types of foods especially the locally produced foods that is nutritious or what they are supposed to eat and be healthy. If they don’t know, it would be difficult for them to eat good food or even how to prepare good food for their children. So if we could get people who will come and teach women, it would bring about massive change in this community. (FGD-men-Nankani-24–34 years)

….When you (refers to the research team) come and teach our people that will help. Also we have health volunteers in this community. We will select them to help this idea to work. That is something we have been yearning for, and we are not getting, so if we get such a thing we will support you because we know it is going to benefit us. (FGD-men-Kasem-35–50 years)

Food aid and nutrition supplementation

Some of the participants recalled several nutrition-specific interventions they had been offered in the past and felt that reintroducing these as well as improving their ability to farm would be good for the nutritional status of their women and children. These nutrition-specific interventions included providing food supplements during antenatal visits and at child welfare clinics.

….So for me if the health workers could give food items to pregnant women and say when you wake up prepare this and eat, take this for the children, use this to prepare food for the children. I think this can help. (FDG-men-Kasem-24–34 years)

At first they used to give us flour from the health facilities to pregnant women or mothers. They would give you the flour to go and prepare it for the child to eat and be strong and healthy. That is no more there at the health facilities, for a very long time. We don’t remember when that was stopped. So when they do that again, it will be good. (FGD-women-Nankani-26–39 years)

Discussion

The current study explored community members’ perceptions of factors affecting the nutrition of women and children and their ideas for contextual–appropriate interventions to improve maternal and child nutrition in rural Northern Ghana. Our study revealed that socio-economic factors recognised to influence access to nutritious food included poverty, poor farm yields and lack of water for dry season agriculture as the main barriers to good nutrition. Subsistence agriculture is the predominant occupation in the study area. Communities depend mainly on rainfall for their farming activities. Not surprisingly, community members mentioned low soil fertility and unreliable rainfall as having negative effects on food production and hence nutritional status of women and children in the area. There were no ethnic differences in views reported on the issues in the current study. It has been previously reported that low agricultural productivity coupled with reliance on rain-fed and low performing largely un-irrigated agricultural lands negatively affects community nutrition(5). To make matters worse, high levels of poverty in the area make it extremely difficult for farmers to get agricultural inputs such as fertiliser and pesticides to use on their farms in order to boost farm yields. Our findings support earlier studies that reported low income levels as responsible for malnutrition(Reference Yimer26,Reference Panth, Gavarkovs and Tamez27) . Others have noted that high cost of hiring farm machinery, inadequate access to credit facilities, poor water supply for irrigation and ineffective technical assistance significantly affected nutrition especially in rural communities(Reference Armah28).

Socially entrenched gender roles and the lack of fulfillment of responsibilities on the part of the men were also widely discussed, mostly by the women. Generally, men are the head of the household and are supposed to provide for the up-keep of the family. Men’s participation and share of their economic responsibilities within the family were considered inadequate and perceived as a barrier to ensuring optimal nutritional status of family members. Although it was the women who voiced the lack of support from the men, some men admitted their lack of involvement(Reference Compaoré, Ouedraogo and Boua18). Men attributed their inability to provide for the family to the general lack of economic opportunities and the increasingly poor returns from agricultural activities. Also, the excessive drinking habits of some men in the area affected their ability to provide for their family members. Community members observed that lack of financial support coupled with lack of income generating opportunities often made it difficult for families to have access to nutritious food. Evidence exists that men’s involvement in child care and feeding could improve nutritional status in rural communities(Reference Juma, Enumah and Wheatley29–Reference Abate and Belachew31).

Despite these numerous challenges, community members proposed various interventions that could improve maternal and child nutrition. They noted that the availability and support to undertake income generating opportunities such as farming and trading especially for women could help solve the poverty situation in the area. They expressed the view that such initiatives would significantly improve maternal and child nutrition largely because the income generated from these activities would make it possible for households to purchase nutritious foods that are not grown in the community. This is consistent with earlier studies reporting that women’s empowerment, employment and social protection could reduce maternal undernutrition, morbidity and mortality(Reference Bhutta, Das and Rizvi8,Reference Rahman, Saima and Goni32) .

The recommendations from the community members in the current study suggest that a focus on agricultural interventions and women’s empowerment would be effective. These types of nutrition-sensitive interventions which also create economic opportunities have been found to improve maternal and child nutrition outcomes(Reference Ruel and Alderman33). Components of interventions which combine agricultural inputs and women’s empowerment include training women to set up and manage poultry-based small businesses and upskilling wider community members in home gardening and food demonstrations. Participants in the current study made a point of asking for nutrition education in the form of food demonstrations to enhance their knowledge on the types of locally produced foods they could eat to improve maternal and child nutrition. These types of interventions have been found to significantly improve child dietary diversity and increase infant length, height and weight z scores in Ghana(Reference Marquis, Colecraft and Kanlisi9). Another agricultural intervention in the neighbouring West African country Burkina Faso also focused on women’s empowerment by dedicating land to women and provided training on agriculture production and income generation. This also produced significant reductions in child wasting and improvements in mothers’ nutrition and empowerment outcomes(Reference Heckert, Olney and Ruel34,Reference Olney, Pedehombga and Ruel35) . Community members in the present study suggested that these types of nutrition-sensitive intervention might be acceptable to them; they wanted support with agricultural outputs, opportunities for women to generate income and education on how to prepare locally grown foods.

Furthermore, measures such as provision of irrigation infrastructure and improved access to agricultural inputs such as high yield seeds, pesticides and fertiliser to boost agricultural productivity were suggested in the current study as ways to improve nutritional status. Study participants suggested that such measures would increase food production and availability all year round and make it easier for households to consume nutritious foods. Evidence from other studies suggests that investment in irrigation infrastructure could be an important poverty alleviation strategy since it boosts agricultural productivity by reducing the risks associated with unreliable rainfall in most of the sub-Saharan African countries including Ghana(Reference Dinye36,Reference Hoddinott, Berhane and Gilligan37) . Small-scale irrigation schemes in the North Eastern region of Ghana have shown to be successful in poverty reduction through creating employment, improving household income source and nutritional status(Reference Adam, Al-hassan and Akolgo38). Community members spoke of changing climates and unreliable rainfall impacting their agricultural outputs and the food they were able to grow and sell. The 2019 Lancet commission on the global ‘syndemic’ of obesity, undernutrition and climate change described the way climate change was exacerbating undernutrition and obesity(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender39). In the context of Navrongo, community members aligned agricultural issues, associated with climate change, to limited access to food and underweight mothers and children. Interventions in this context therefore need to account for effects of climate change and fluctuations in the traditional patterns of the seasons.

Continued investments in nutrition-sensitive interventions could help prevent maternal and child undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and mortality especially in rural communities(Reference Bhutta, Das and Rizvi8,Reference Ruel and Alderman33) . Also, involvement of community members in nutrition interventions could help them identify their own initiatives to improve nutrition(Reference Masters, Rosettie and Kranz7,Reference Robinson16) . It has been demonstrated that good nutrition in early life is the foundation for long-term good health and a healthy dietary pattern reduces maternal and child undernutrition(Reference Mohammed, Khanum and Mamatha40–Reference Kumar42). If the proposed strategies identified by study participants are implemented and sustained, this could help to improve maternal and child nutrition in the area.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this research is the random selection and representation of men and women of different age groups and ethnicity in the FGD. This allowed us to reflect the diversity of experience of men and women in this community and a range of information on potential interventions to improve maternal and child nutrition. The main limitation of the study was that the interviews were conducted in the local languages of the study area, tape recorded, transcribed and translated into English. It is possible that some statements made in the local languages may have lost their original meaning in the English translation. However, the interviews were transcribed by graduate research officers who are native speakers with experience in transcribing qualitative interviews. Any loss of meaning during the translation was minimised and did not affect the findings of the study.

Conclusion

Nutrition plays an important role in maternal and child health. Based on our interpretation of the data, we recommend specific contextual and nutrition-sensitive interventions such as improved irrigation of agricultural land, provision of agricultural inputs to improve crop yield in combination with community education about how to maximise the nutritional benefits of locally available foods as avenues to improve maternal and child nutrition. The impacts of climate change also need to be accounted for, however, when designing agricultural interventions to improve maternal and child nutrition in this context.

It is also recommended that community members’ involvement in designing and implementing practical nutrition programmes at the community level could lead to improvement in maternal and child nutritional intake and sustainability of such programmes. It is therefore important for stakeholders such as the Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Ministry of Health, Ghana Health Service and civil society organisations to take appropriate steps towards supporting community initiated strategies to improving maternal and child nutrition in Ghana.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to all the study participants for sharing their experiences and views with the research team. We are also grateful to all individuals who supported the study team in one way or the other during data collection and analysis. Financial support: The current research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (17\63\154) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: Substantial contributions to conception and design: C.D., E.A.N., M.-L.N. and M.B. Data acquisition: C.D., J.K.A., E.D., P.B. and E.W.N. Analysis and/or interpretation: C.D., S.T.C., J.K.A., E.D., R.A. and M.B. Drafting the article: C.D., S.T.C., J.K.A., E.W.N. and E.D. Critically revised the article for important intellectual content: E.A.N., D.W., S.H.K., M.A.D., W.O., R.A., P.W., A.R.O., M.-L.N. and M.B. Final approval of the article: C.D., E.A.N., S.T.C., J.K.A., E.D., P.B., E.W.N., D.A.-B., D.W., S.H.K., M.A.D., W.O., R.A., P.W., A.R.O., M.-L.N. and M.B. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Navrongo Health Research Centre Institutional Review Board (approval no. NHRCIRB322) and the University of Southampton Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (no. 47290). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.