1. Introduction

Child Physical Maltreatment (CPM) is a global public health issue, with 23% of the European adult population reporting having been physically maltreated in childhood Reference Sethi, Bellis, Hughes, Gilbert, Mitis and Galea[1]. CPM is defined as violence perpetrated by a household member (usually a parent or a primary caregiver) towards the child. CPM includes the child being beaten, kicked, burnt, hit with belts or other objects, or being threatened with knives or other weapons Reference Bifulco, Brown and Harris[2]. These violent behaviors substantially increase the risk of physical harm and the infliction of non-accidental physical injury to a child, including bruises, bites, bone fractures, cuts, welts, and burns Reference Bifulco, Brown and Harris[2]. The presence of physical injury resulting from a violent behavior toward the child is considered as an operational marker of the CPM severity Reference Sethi, Bellis, Hughes, Gilbert, Mitis and Galea[3–Reference Griffin and Amodeo5]. In accordance with the widely-adopted Modified Maltreatment Classification System, CMP severity is operationalized as a dimensional construct that describes different levels of the seriousness of a given act of maltreatment in function of the harmfulness of physical sequelae caused by the violent behavior Reference Bifulco, Brown and Harris[4, Reference English and Investigators6]. CMP severity might range from dangerous behaviors but with no physical injuries or marks indicated (the lowest level of severity) to permanent disability, scarring, disfigurement, or fatality (the highest level of severity) Reference English and Investigators[6].

Strong relationships between criteria of CPM classification (such as CPM type, frequency, chronicity) and psychopathology symptoms and/or psychiatric disorders in adults have been described in literature Reference Litrownik, Lau, Briggs, Newton, Romney and Dubowitz[7, Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos8]. In particular, the frequency and chronicity of CPM exposure are being associated with an increased risk of earlier onset and higher severity of psychopathology symptoms, including depression, anxiety, alcohol dependence, psychotic symptoms, posttraumatic symptoms, and suicidal behaviors Reference Manly, Cicchetti and Barnett[9–Reference Hayashi, Okamoto, Takagaki, Okada, Toki and Inoue11]. Despite these well-established findings, differential associations between distinct CPM patterns and the emergence of specific psychological problems in adulthood have remained surprisingly unexplored at an empirical level Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos[8]. Little is known about whether specific subgroups of CPM exposure may report a higher risk of psychopathology symptoms in adulthood.

This limitation might be partially explained through methodological reasons. Previous research has neglected the potential clinical utility of discriminating CPM behaviors from the physical sequelae resulting from CPM. Prior empirical work has combined the presence and/or frequency of CPM behaviors (e.g., beat, hit with a belt) and CPM physical sequelae (e.g., bruises, fractures) into a single conceptual category to predict adverse psychological consequences in adults Reference Griffin and Amodeo[12–Reference Lindert, von Ehrenstein, Grashow, Gal, Braehler and Weisskopf14]. This methodological option is preventing the detection of differential associations between distinct CPM histories and psychopathology symptoms in adulthood. This is particularly critical since prior research in other types of child abuse suggest that the presence of abuse-related physical sequelae is associated with a heightened risk of adult psychiatric disorders Reference English and Investigators[15, Reference Bernet and Stein16]. In particular, some studies show that adults who were exposed to severe forms of sexual abuse (e.g., injuries related to sexual abuse) reported higher prevalence of mental health problems than non-exposed or low-severity exposed adults Reference Gilbert, Bauer, Carroll and Downs[17–Reference Cutajar, Mullen, Ogloff, Thomas, Wells and Spataro19]. These findings in sexual abuse suggest that a similar pattern of associations in CPM may emerge, in which a more detrimental association between the history of CPM with physical sequelae and later psychopathology symptoms might be expected.

To our knowledge, no previous research has tested this hypothesis directly. However, this assumption is conceptually supported. First, as physical sequelae are more likely to occur during more violent episodes of maltreatment, they are likely to be perceived as significant and real threats to survival. According to the evolutionary-developmental frameworks of adaptative development Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos[20, Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff21], children facing life-threatening environments develop and activate a pattern of physiological, behavioral, and emotional responses to monitorize and respond to an environment of imminent and inescapable threat. The continual activation of these responses is adaptive to competently survive in violent contexts, but it has long-term developmental costs, adversely affecting the development of the nervous, neuroendocrine, and immune systems Reference Danese and McEwen[22]. More specifically, children exposed to highly-threatening environments develop overtime altered nervous and neuroendocrine functional activity characterized by high responsivity and basal activity in both the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA-axis) and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), as well as by a low tone and responsivity of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff[21]. This pattern of stress reactivity functioning is thought to be the major mechanism linking highly adverse experiences (e.g., exposure to physical sequelae CPM) and risk of psychopathology Reference Del Giudice and Ellis[23].

The exposure to the physical sequelae of CPM might also induce children to interpret the parenting subsystem as an even more threating, unpredictable, and harmful environment Reference Davies and Martin[24]. The emotional security theory suggests that such a stressful nurturing environment undermines children’s sense of emotional security and safety in parent-child relationships, impairing children’s internal representations of the abusive parent as a reliable caregiver to fulfill their instrumental and emotional needs Reference Cecil, Viding, Fearon, Glaser and McCrory[24, Reference Davies, Forman, Rasi and Stevens25]. This may lead to a disturbance in attachment security and development of hypo and overreactive emotional and behavioral strategies to cope with such adverse parenting outcomes Reference Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van Ijzendoorn[20]. As a result, these emotional and behavioral difficulties exert a deleterious impact on individuals’ abilities to successfully negotiate subsequent developmental tasks, increasing the risk of later psychopathology symptoms Reference Coe, Davies and Sturge-Apple[26].

To provide additional insight into the associations between the history of CPM and psychopathology symptoms in adulthood, it is also crucial to consider that distinct associations may occur between CPM (with and without sequelae) and different psychopathology dimensions. Past research has mainly examined the association between CPM and depression and anxiety disorders Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos[27]. In addition, previous studies tested primarily this association in clinical samples, using almost exclusively golden-standard measures to diagnose psychiatric disorders Reference Lowe, Meyers, Galea, Aiello, Uddin and Wildman[28, Reference Green, McLaughlin, Berglund, Gruber, Sampson and Zaslavsky29]. This categorical approach based on the notion of the presence or absence of psychopathology symptoms Reference Widiger, Gore, Widiger and Gore[30] precludes, however, the possibility of different histories of CPM exposure being associated with the co-occurrence of distinct types of clinical symptoms. Therefore, a dimensional approach to psychopathology allows a more fine-grained analysis of the full-range presence of symptoms, regardless of whether the formal criteria of diagnosis have been met Reference Hayashi, Okamoto, Takagaki, Okada, Toki and Inoue[30, Reference Hudziak, Achenbach, Althoff and Pine31]. In particular, by assuming a continuum in psychopathology intensity, this approach provides additional insights into the comorbidity of symptoms, as well as whether and to what extent the psychopathology grouping of symptoms varies under distinct consequences of CPM.

In order to address these limitations, this study sought to examine differential associations between three types of histories of CPM and psychopathology symptoms in adulthood. Consistent with our rationale, we hypothesized that adults with no history of CPM would show the lowest levels of psychopathology when compared with adults exposed to CPM with or without physical sequelae. We also hypothesized that, among adults exposed to CPM, those who reported CPM-related physical sequelae would exhibit the highest levels of symptoms across all assessed psychopathological dimensions.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

This cross-sectional study is a secondary analysis of existing data of the Portuguese National Representative Study of Psychosocial Context of Child Abuse (PNRSAB). The total sample of the PNRSAB The primary research goals of the PNRSAB were to describe the prevalence of child physical maltreatment and to examine the associations between CPM and psychopathology symptoms.

The total sample comprised 941 adults (55% women). Participants were mothers and fathers of children randomly selected in five public elementary schools in Northern Portugal (sample selection procedures are described in-depth to follow Reference Figueiredo, Bifulco, Paiva, Maia, Fernandes and Matos[32]). After being informed about the research aims and ethical procedures, adults who consented to participate completed and returned the assessment protocols and the letters of informed consent in sealed envelopes provided by the research team. This community school-based survey received ethical approval from the regional education authorities (Direcção Regional da Educação do Norte). A comparison to the national population statistics for marital status, education level, and income in the year that participants’ data were collected revealed that the current sample is representative of the Northern Portuguese population Reference Lamela and Figueiredo[33].

The participants’ mean age was 37.15 years (SD = 6.26; range = 22–59). With respect to marital status, 91.3% of the sample were married or in cohabitation, and 8.7% were divorced, single, or widowed. Five hundred and ninety-seven (63.4%) participants had until a 9th-grade compulsory education level, and 344 (36.6%) participants had a high school or college degree. Most mothers (66.5%) reported an income lower than the average national salary (765 €).

2.2. Measures

CPM perpetrated by a parent or a primary caregiver during childhood and/or adolescence (0–18 years) was assessed with the Childhood History Questionnaire (CHQ)Reference Milner, Robertson and Rogers[34]. The CHQ is a retrospective self-report measure that assesses adults’ exposure to physical abusive behaviors and CPM-related physical sequelae during childhood and adolescence. The main CHQ question is: “As a child, did you receive any of the following from one of your parents or another adult?" In a 5-point Likert-scale (from 0 to 4), respondents were asked to recall the presence and frequency (i.e., never, rarely, occasionally, often, and very often) of four physically abusive behaviors (whipping, slapping/kicking, poking/punching, and hair-pulling). Respondents were then requested to indicate the presence of five potential physical sequelae resulting from those physical abusive behaviors (i.e., bruises/welts, cuts/scratches, dislocations, burns, and bone fractures). Three scoring methods can be applied to analyze CHQ answers. The first method is the computation of a total score by summing respondents’ answers to each of the nine items; the second method is the computation of two subtotal scores: a subtotal score for the frequency of the physically abusive behaviors (4 items), and a subtotal score for the frequency of CPM-related physical sequelae (5 items). The third method is a dichotomizing procedure by scoring the presence or absence of any exposure to physically abusive behaviors and presence or absence of any physical sequelae related to CPM exposure. As the adults’ childhood history of CPM exposure was not a primary variable of interest of the PNRSAB, the CHQ were manually scored by the research team, and only the final scores were entered in the database. Data regarding to frequency of exposure to physically abusive behaviors were scored using the second method (computing a subtotal score), and the third method (dichotomizing procedure) was employed to score the presence/absence of any CPM-related physical sequelae. The Portuguese version of the CHQ showed good psychometric properties Reference Figueiredo, Bifulco, Paiva, Maia, Fernandes and Matos[32]. In the current sample, internal consistency was very good (Kuder-Richardson-20 =.81).

Psychopathology symptoms were measured with the Brief Symptom Inventory Reference Derogatis and Melisaratos[35]. This widely-used 53-item self-report inventory assesses nine primary psychopathology symptom dimensions: depression, hostility, anxiety, phobic anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, psychoticism, paranoid ideation, somatization, and interpersonal sensitivity. Each item is rated on a 5-Likert point scale (from 0 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘extremely’). Additionally, the General Severity Index (GSI) was computed, since it is the single best global indicator of current psychopathology distress levels. Higher scores represent greater psychopathology symptoms. The Portuguese version of the BSI showed adequate psychometric properties Reference Canavarro, Simões, Gonçalves and Almeida[36]. Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample ranged from 0.73 (psychoticism subscale) to 0.88 (depression subscale).

2.3. Participants’ assignment to the CMP groups

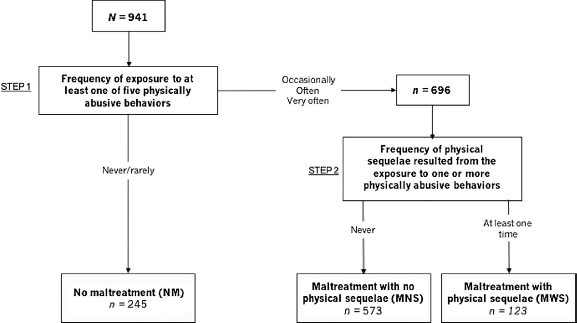

The CHQ was used to assign participants to one of the three physical maltreatment groups, according to their experience of physical maltreatment until 18 years of age. The assignment was conducted using a two-step procedure, based on participants’ answers regarding (1) the exposure to physically abusive behaviors and (2) the presence of physical sequelae resulted from the exposure to physically abusive behaviors. The groups’ assignment procedure is displayed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Procedure for Participants’ Assignment to the CPM Groups.

In step 1, we analyzed the participants’ reports about the exposure to the five CHQ listed physically abusive behaviors. Respondents who indicated never or rarely experiencing any of those physically abusive behaviors were assigned to the non-maltreatment group (NM; N = 245, 26% of the total sample). We decided to include participants with rare experiences of CPM in the non-maltreated group based on recent work that showed that single or rare events of physical abuse in childhood did not increase the risk of psychopathology symptoms in adulthood, either for women or men Reference Agnew-Blais and Danese[37–Reference Greenfield and Marks39].

The remaining 696 participants reported they had been occasionally, often, or very often exposed to at least one of physically abusive behaviors. In step 2, we analyzed answers of these remaining 696 participants regarding the presence of physical sequelae (i.e., bruise/welt, cut/scratch, dislocation, burn, or bone fracture) resulted from physically abusive behaviors. Participants reporting that never suffered physical sequelae resulting from physically abusive behaviors were assigned to the maltreatment with no physical sequelae group (MNS; N = 573, 61% of the total sample). In contrast, participants who reported that they had suffered at least one physical sequelae resulting from a physically abusive behavior perpetrated by a parent were assigned to the maltreatment with physical sequelae group (MWS; N = 123, 13% of the total sample).

2.4. Data analysis

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to examine group differences in age, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted to assess group differences in gender, marital status, years of education, and family income/month distribution. Differences between the three groups in the psychopathology dimensions were first examined using ANOVA, followed by ANCOVA (analyses of covariance), adjusting for potential covariates. As multiple tests were conducted, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests were performed in order to prevent Type I Error.

3. Results

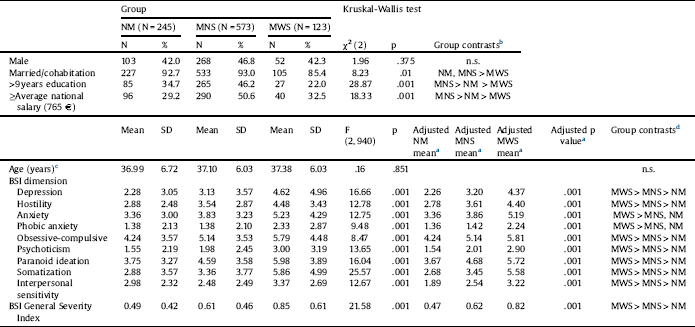

ANOVA and Independent Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted to test differences between the groups in socio-demographic variables. Differences between groups were found in marital status, years of education, and family income/month (Table 1). Dunn’s post hoc tests revealed that, when compared with the other groups, MWS group exhibited the lowest proportion of married/cohabiting participants and also the lowest proportion of participants with more of 9 years of education and with a higher income than the average national salary. When compared with the NM group, MNS group exhibited the highest proportion of participants with more of 9 years of education and with a higher income than the average national salary. No differences between MNS and NM groups were found in the proportion of married/cohabiting participants. No differences between groups were found in participants’ age and gender (Table 1).

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics, Observed and Adjusted MeansFootnote a in BSI Dimensions in No Maltreatment (NM), Maltreatment with no Sequelae (MNS), and Maltreatment with Sequelae (MWS), and Group Contrasts.

a Adjusted for marital status, education and income per month.

b Significant group differences on Kruskal-Wallis test at p <.05 using Dunn’s post hoc test.

c Age ranges: NM group, 22–64 years; MNS group, 22–63 years; MWS group, 24–58 years.

d Significant group differences on ANOVA and ANCOVA at p <.05 using Bonferroni-corrected post hoc test.

Next, ANOVA indicated significant group differences on all BSI dimensions, in which participants of the MWS group exhibited significantly higher scores than the other two groups. Table 1 displays mean unadjusted of BSI dimensions in the three maltreatment groups. ANCOVA was used to statistically control the potential effects of socio-demographic variables. Marital status, years of education, and family income/month were used as covariates since differences between groups were found on those variables. Table 1 shows adjusted means of BSI dimensions, with ANCOVA results revealing the same significant differences between groups. Neither the group means nor the significance levels were substantially changed after covariates adjustment. Participants of the MWS group obtained a GSI mean higher than the other two groups, while participants of the MNS group showed a GSI mean higher than participants of the NM group (Table 1).

4. Discussion

This study sought to test the associations between exposure to CPM with and without physical sequelae and psychopathology symptoms in a community sample of Portuguese adults. Our findings show that individuals within the MWS group reported the highest scores of symptoms in all assessed psychopathology dimensions. We also found that individuals within the NM group exhibited the lowest levels of psychopathology symptoms, with the exception in BSI anxiety-related subscales. Our findings are consistent with prior reports of an association between CPM and psychopathology symptoms in adulthood Reference Cecil, Viding, Fearon, Glaser and McCrory[9–Reference Hayashi, Okamoto, Takagaki, Okada, Toki and Inoue11].

However, for the first time in literature, our study provides empirical evidence of the higher risk of psychopathology symptoms for the adults who reported the presence of physical sequelae related to CPM, including depressive, somatic, and psychotic symptoms. Taken together, the present findings offer initial support for the clinical and conceptual utility of discriminating CPM behaviors from CPM physical sequelae in the assessment of CPM experiences and its association with later psychopathology symptoms. The current research reveals that psychopathology symptoms’ scores were significantly distinct between the two groups of CPM, suggesting that physical sequelae may operate as a distinct risk factor in the mental health trajectories. Although hypothetical, we believe that these findings are consistent with emerging evolutionary-developmental perspectives of adaptive development which places the development of the stress response system within its proximal ecology when interpreting individual differences in mental health outcomes Reference Del Giudice and Ellis[23]. These frameworks assert that children calibrate their behavior in ways to increase their fitness within a specific environmental condition. In an environment of CPM episodes that cause physical injuries, children have to adapt their behavior to face immediate and unpredictable threats, including hypervigilance and extreme fight-flight responses. These behavioral adaptations in such hard conditions are mediated by the nervous and neuroendocrine systems, resulting in a specific physiological profile Reference Del Giudice and Ellis[23]. This vigilant profile (i.e., low to moderate PNS responsivity, and high SNS and HPA responsivity) is associated with elevated levels of aggressive/antisocial and depression/anxiety behaviors Reference Lindert, von Ehrenstein, Grashow, Gal, Braehler and Weisskopf[21, Reference Ellis and Del Giudice40]. Despite its adaptative function to struggle with immediate threats in childhood, this physiological-behavioral pattern hampers individuals’ efforts to cope successfully with later changes in their environments, leading to psychopathology symptoms in adulthood. Based on these frameworks, as CPM with physical injuries might be perceived as more threatening to survival, children exposed to such violent forms of CPM have to perform higher behavioral adaptations that are associated with extreme variations of this vigilant phenotype. Therefore, when compared with the other two groups, it makes sense that adults who report physical sequelae of CPM are those who report higher mental health problems. In partial support of this assertion, empirical research has associated the exposure to maltreatment with this particular physiological pattern and later psychopathology symptoms Reference Quevedo, Doty, Roos and Anker[41, Reference Doom, Cicchetti and Rogosch42]. For example, a recent longitudinal study showed that maltreated youth were more likely than non-maltreated youth to present low cortisol levels, suggesting a high HPA responsivity Reference Peckins, Susman, Negriff, Noll and Trickett[43]. However, none of these studies discriminated CPM behaviors from CPM physical sequelae.

By extension, our results also raise the possibility that the presence of physical sequelae in CPM episodes could operate as a stronger indicator of higher exposure to a risk constellation in childhood Reference Repetti, Taylor and Seeman[44, Reference Lamela and Figueiredo45]. First, physical sequelae are more likely to be inflicted during more severe episodes of CPM Reference Milner, Robertson and Rogers[34]. Parents who perpetrate severe CPM are more likely to exhibit psychiatric disorders Reference Walsh, MacMillan and Jamieson[46], higher anger dysregulation Reference Rodriguez and Richardson[47], and higher social risk Reference Cancian, Yang and Slack[48], which are also documented as significant distal risk factors for the emergence of psychopathology symptoms in adulthood. In addition, CPM is highly likely to co-occur with other family risk factors Reference Turner, Finkelhor, Ormrod, Hamby, Leeb and Mercy[49] that cumulatively may constrain the developmental acquisition of internal and external adaptative coping resources that buffer the effects of exposure to stress Reference Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, Polo-Tomás and Taylor[50]. Exposure to multiple sources of stress is thought to be a cumulative chain of risk that is longitudinally linked with the dysregulation of children’s psychological, behavioral, and neurobiological self-regulatory processes that ultimately increases individuals’ vulnerability to psychopathology in adulthood Reference Kessler, McLaughlin, Green, Gruber, Sampson and Zaslavsky[51–Reference Evans and Cassells53]. Therefore, as CPM with physical sequelae is likely to co-occur with other family adversities it may also operate as a marker of exposure to cumulative risk during childhood that also increases the odds of psychopathology symptoms in adulthood Reference Evans, Li and Whipple[54]. Thus, differences in psychopathology dimensions across CPM groups may suggest that individuals exposed to CPM with physical sequelae may be exposed to a risk constellation beyond CPM. Further research is needed to address the role of the cumulative effect of stressors on the association between CPM and adult psychopathology symptoms.

Several limitations warrant discussion. First, the presence of physical sequelae resulting from CPM exposure assessed via CHQ was coded and entered in the PNRSAB database as a dichotomous variable (presence vs. absence of physical sequelae). This prior methodological option prevented the examination of the association between different levels of severity of physical sequelae and adults’ psychopathology symptoms. The MWS group congregated all participants who reported physical sequelae regardless their severity and frequency. This dichotomization option precluded the inspection of the severity of CPM as a continuous dimension and also the examination of potential subtypes of severity in the MWS group. Despite our study was the first to provide empirical support for the association between CPM-related physical injuries and adults’ psychopathology symptoms, future research should expand our results by controlling the CPM severity and also by exploring the differential association between different levels of physical sequelae and later mental health outcomes. Second, all constructs were only assessed using self-report measures. Despite that all measures used in the current research have demonstrated significant associations with interviewing and observational measures, multi-informant and multimethod procedures could have contributed to a higher accuracy of measurement and also decreased possible shared method variance. This is significantly more important in the assessment of CPM exposure since some previous research suggests moderate CPM retrospective self-reports and official records Reference Glover, Burns, Vargas, Sciolla, Zhang and Glover[55, Reference Pinto and Maia56]. Second, temporal variations in the severity of psychopathology symptoms might be expected, as suggested by longitudinal studies Reference Mezuk and Kendler[57]. However, due to the cross-sectional design of the current study, the potential differential impact of these changes over time on our findings was not examined. Finally, the current research was only conducted mainly with young adults with children. While this relative homogeneity augments statistical confidence in the associations found, this limited variability restrains the generalization of these findings from adults without children or older adults.

4.1. Clinical implications

Our results may also have three major clinical implications. First, by showing differential associations between exposure to CPM with and without physical sequelae and adult psychopathology symptoms, mental health professionals should not only assess CPM behaviors but also routinely include measures of CPM physical sequelae in their assessment protocols. In addition, as CPM subgroups were associated with different psychopathology dimensions, our results may imply that clinical assessment can benefit from the inclusion of a dimensional approach of psychopathology, rather than a categorical approach of assessment of these constructs. A dimensional approach for the assessment of psychopathology may be required for the translation of our findings into more effective clinical interventions in primary care settings. Second, by identifying specific subgroups reporting a higher risk of specific problems in parenting and co-parenting, our findings may raise the necessity of selective preventive interventions. In primary care settings, clinicians should especially screen psychopathology symptoms in adults with history of exposure to CPM with physical sequelae. In particular, mental health professionals could identify individuals with high cognitive-affective depression symptoms and somatic complaints for early support and intervention. Finally, our results could be applied in the assessment of the early onset of psychopathology symptoms in children exposed to CPM. These findings highlight that early intervention and prevention initiatives should be designed for those children who report physical injuries related to CPM episodes because the presence of these injuries increases the risk of more detrimental mental health outcomes in adulthood.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.