Introduction

Most lower houses rely on electoral systems based on regional constituencies, enabling to represent all territories in a given country. According to Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967), descriptive representation is based on the fact that the representatives and the represented share a series of similar characteristics, such as being born in the same region. Although descriptive representation is only one dimension of political representation, sharing characteristics with candidates can be an important factor for voters. Parties are aware of this fact and take strategic decisions based on this criterion.

MPs are not necessarily born in the constituency that they represent. Mobility across constituencies is frequent, obeying criteria such as personal interest and motivations, parties’ strategic decisions, and electoral needs depending on the situation (Pedersen, Kjaer, and Ekiassen Reference Pedersen, Kjaer and Eliassen2007). This territorial mobility, defined in this work as the fact of being elected as an MP in a different autonomous community (comunidad autónoma) than one’s place of birth, has rarely been taken into account in the literature, with some exceptions (Latner and McGann Reference Latner and McGann2005; Pedersen, Kjaer, and Ekiassen Reference Pedersen, Kjaer and Eliassen2007; Jakub Reference Jakub2017). Many questions remain unanswered. What effects do the movements of these MPs—sometimes called “parachutists” or “carpetbaggers”—have on territorial descriptive representation in Congress? Can any mobility patterns or trends be identified? Is territorial mobility related to politics?

To fill this knowledge gap, this article proposes to study territorial descriptive representation by focusing on the case of Spanish MPs in the Congress of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados) since the democratic transition (1978). Territorial descriptive representation compares the number of seats of each autonomous community and the number of MPs born in the corresponding region. When these two data match, territorial descriptive representation is adjusted to the population size of each autonomous community—on which their number of seats depends. The manner in which MP mobility may affect the territorial descriptive representation is then analyzed.

Spain is a relevant case study. Indeed, strong territorial tensions still shake national politics due to the mobilization of its peripheries. Spain’s territorial configuration is complex, and the country is often described as a decentralized state with many federal features (Ruipérez Reference Ruipérez1993; Blanco-Valdés Reference Blanco-Valdés2012; Aja Reference Aja2014). Indeed, this State of autonomies (Estado de las autonomías) is divided into 17 autonomous communities—encompassing a total of 50 provinces—plus two autonomous cities (Ceuta and Melilla). At the same time, however, Spain retains some centralist elements, such as provincial divisions, the presence of state administrative officials representing central ministries in the provinces and regions (delegados del gobierno), and a powerful national capital, Madrid, which concentrates all the central political institutions.

Within this framework, it is worth noting the diversity of the territorial peripheries, which present different levels of identity and degrees of integration with respect to the central state. Among them, we find the so-called four “historical nationalities” (nacionalidades históricas): the Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia, and Andalusia. Of these, both the Basque Country and Catalonia would fit the description of “failed cores” (Eisenstadt and Rokkan Reference Eisenstadt and Rokkan1973; Rokkan and Urwin Reference Rokkan and Urwin1983) because a significant number of Basques and Catalans feel they are deeply distinct from the rest of Spain. In turn, Galicia and Andalusia would rather respond to the typology of “pure peripheries,” as they are more dependent and assimilated in the central state. The notion of pure peripheries could also be used to label the insular territories (the Canary Islands and the Balearic Islands) and two additional regions with specific features (the Valencian Community and Navarre).

The concept of territorial representation is particularly apparent in the Spanish lower house. Although Article 66 of the 1978 Constitution affirms that the Congress represents all Spanish people, the electoral system consists of 52 constituencies (one per province, plus Ceuta and Melilla) that elect the MPs to the Congreso. The number of seats in each constituency is proportional to the population (with a minimum of two seats), enabling the (rather disproportional) territorial representation of the entire country. This article takes the autonomous community as a territorial reference (the MPs’ birthplace) since the 50 provinces are grouped into 17 autonomous communities (plus the two autonomous cities) which have superior territorial, administrative, and political powers.

The descriptive analysis performed below was possible thanks to the BAPOLCON data set, which includes sociodemographic and political variables relating to all the deputies elected from the constituent legislature in 1977 to the XIV legislature in 2020. The present article is structured as described next. First, a literature review introduces the territorial analyses that have hitherto been conducted on the legislative power in Spain and elsewhere. The following section describes the methodology following in the study. The results are then presented, divided into the following subsections: an overview of localism in the Spanish Congress; the territorial origins and constituencies of native and non-native MPs; the role of political parties; the relevance of the hyper elites within the lower chamber; and a proposal of models for classifying territories according to the territorial dynamics of Spanish MPs. The article concludes with a discussion of the main results with respect to the literature and future lines of research.

Literature Review

In culturally diverse countries, such as Belgium (Deschouwer Reference Deschouwer2006) and Switzerland (Stojanović Reference Stojanović2016), the principle of territorial distribution among ministers is explicitly guaranteed by constitutional and legal provisions. These systems are sometimes defined as “consociations” in accordance with Lijphart’s (Reference Lijphart1969) definition. However, in most states, territorial balance in the council of ministers is not mandatory. This balance depends on political variables relating to the networks of influence, the parties’ internal logic, or the positioning of peripheral regions in the political center. This is the case of Spain, where the geographical distribution of ministers and civil servants is not regulated by law. Nevertheless, as demonstrated by Spanish scholars (Cuenca and Miranda Reference Cuenca and Miranda1987; Linz, Jerez, and Corzo Reference Linz, Jerez and Corzo2002), territorial equilibrium matters. The territorial networks in central institutions (Villena-Oliver and Aldeguer-Cerdà Reference Villena-Oliver and Aldeguer-Cerdà2017), and the regions of recruitment of state-wide parties—conservatives in the center of the peninsula and progressives in the Mediterranean regions and Northern Spain (Rodríguez-Teruel Reference Rodríguez-Teruel2011, Reference Rodríguez-Teruel2013)—have already been brought to the fore.

With the development of Spain’s autonomous communities came territorial elites connected to them. The creation of territorial institutions, with parliaments and executives, modeled on those of the state, fostered the emergence of regional elites (Stolz Reference Stolz2013). Since then, in Spain, state and regional politics have constituted two equally attractive arenas in which to pursue political careers. The literature has a name for this phenomenon: the “integrated career model” (Dodeigne Reference Dodeigne2018, 730). Two major factors must be in place for this to occur: first, a high level of professionalization; and second, a strong regional identity that is overt and politicized enough to make sub-state institutions symbolically independent vis-à-vis the state (Stolz Reference Stolz2003, 243). This model is consolidated in Catalonia, where the two arenas, Spanish and Catalan, have an equal weight in MPs’ political careers, with neither being a step ahead of the other (Slotz Reference Stolz2011, 233).

Except for the few states with a single constituency (Israel and the Netherlands, for instance), the electoral systems designed for electing MPs usually divide the national territory into local electoral districts so as to guarantee a certain degree of territorial representation. Consequently, territorial representation in parliaments has been studied less than that in executives. However, some studies, such as that of Latner and McGann (Reference Latner and McGann2005), have indicated that even in cases of single constituency parliaments, geographical representation is quite balanced, although not perfectly so. Metropolitan areas are somewhat overrepresented, as are the more remote peripheral areas, to the detriment of regions adjacent to the central region. A study with similar characteristics was led by Jakub (Reference Jakub2017) on the Slovak Parliament. He found that MPs residing in the capital, Bratislava, were three times overrepresented compared with the proportional number of voters in that region. In the case of the United Kingdom, Berry (Reference Berry2013) analyzed the proportion of MPs who were born and won a seat in Westminster in the same region. This latter study showed the overrepresentation of the capital, London, and Scotland.

As previously mentioned, the Spanish Constitution is unclear regarding the concept of territorial representation. On the one hand, its article 68.1 affirms that the Congress represents all Spanish people. On the other, since 1978, article 68.2 establishes the province as an electoral district for the Congress of Deputies. Moreover, decision 19/2011 of the Constitutional Court states that “[…] the electoral system, in addition to being proportional, must ensure the representation of the different areas of the territory.” In other words, territorial representation applies not only to the appointment of senators to the upper house (Senado)—supposedly created to represent the territorial interests—but also to that of MPs to the Congress of Deputies.

Of interest, it should be noted that this institutional design was the product of historical bargaining. Territorial representation based on provincial constituencies appeared during the pre-constitutional debates held at the Francoist Court of Procurators and was included in the Law of Political Reform 1/1977 during the Transition (Herrero de Miñón Reference Herrero de Miñón2017). The most conservative procurators, prone to a majority system, presented the provincial constituency (created in 1833) as a corrector of the principle of proportionality, which in turn was imposed as a key element of the Spanish electoral system (Alzaga Reference Alzaga2020; Soriano Reference Soriano2020). This corrective purpose of the provincial constituencies has since been successfully implemented, granting overrepresentation to the less populated provinces. Although the democratic opposition criticized this point of the electoral law during the Transition, provinces remained the exclusive constituencies for electing the members of the Congreso.

Paradoxically, one of the side effects of this seminal decision adopted under a centralist-authoritarian regime was the constitution of provincial fiefs for the main state-wide parties as well as for the region-wide formations. This is especially the case in the areas with a distinct feeling of belonging, such as the Basque Country or Catalonia, where specific electoral markets arose under the pressure of ethnonationalist parties. The support of ethnonationalist parties has also been necessary on several occasions to secure most national cabinets led by the Partido Socialista (Socialist Party -PSOE- in 1993, 2008, 2018—through a vote of no confidence—and 2020) and the Partido Popular (People’s Party -PP- in 1996). As stressed by Coller et al. (Reference Coller, Portillo, Domínguez, Escobar and García2018), Basque and Catalan nationalist parties include more MPs who were born in their autonomous communities in their lists than the state-wide parties that also obtain representation in those peripheral constituencies.

In the power structures of parliaments, there are privileged positions, occupied by MPs with a relevant position in their parliamentary group. The Permanent Deputation and the Board of Spokespersons usually include the MPs with the most central position in parliamentary life, thus constituting a hyper elite within the elite (Santana, Aguilar, and Coller Reference Santana, Aguilar and Coller2016). The Permanent Deputation (Diputación Permanente) is the body that rules the chamber when the Plenary cannot meet or is dissolved between legislatures. Its members are appointed by the parliamentary groups, in proportion to their number of seats. The Board of Spokespersons (Junta de Portavoces) comprises the spokespeople of the parliamentary groups. The spokespersons are extremely active in the day-to-day politics of the Congress and are considerably influential within their respective groups. The positions of power designated by the parliamentary group’s leaders tend to follow Putnam’s (Reference Putnam1976) law of increasing disproportion, whereby the more disadvantaged a social group, the less it is represented at the highest levels of power. This was confirmed, for example, by Santana, Aguilar, and Coller (Reference Santana, Aguilar and Coller2016) regarding the presence of women in the hyper elite of regional parliaments in Spain. In the hyper elite, however, a principle of territorial representation no longer acts as a mediator as it did in the provincial constituencies for the entire Congress. In other words, an analysis of the territorial balance in the hyper elite will reflect the political decisions of the parliamentary groups without institutional correctors.

Methodology

This article addresses the territorial component in Pitkin’s descriptive representation, which is based on the common characteristics shared by representatives and the represented. It is important to clarify that the territorial component (the autonomous community of birth of the MPs) is only one component among others of the descriptive representation, such as gender or age. Similarly, descriptive representation is only one dimension of representation. Being born in an autonomous community does not necessarily imply better or worse representation, although it does at the descriptive level. Indeed, one advantage of working with the territorial dimension of the descriptive representation is that objective data can be used, such as the place of birth. However, the interest in studying MPs’ origins in relation to their seats (descriptive territorial representation) lies in understanding MP mobility and the possible dynamics of territorial tensions.

A descriptive statistical analysis, thus, was conducted to study territorial descriptive representation in the Spanish Parliament from 1977 to 2020. The main analytical tool was a modified version of the Territorial Representation Index (TRI) (Cuenca and Miranda Reference Cuenca and Miranda1987), which links MPs’ birthplaces to the size of the constituencies in which they are elected. The TRI measures different levels of territorial descriptive representation per region. The data were compiled using the BAPOLCON data set,Footnote 1 which contains records of the 2,522 deputies who have occupied one of the 5,250 seats in Congress since 1977 (constituent legislature) until April 2020 (XIV legislature). The latest fieldwork took place from November 2019 to April 2020, when the last modification was recorded.Footnote 2 Although the electoral constituency in Spain is provincial, we analyzed the data by autonomous community. The reason for this decision was that the comunidades autónomas exert the greatest influence on the feeling of belonging in Spain: territorial adscription is expressed in regional terms rather than in local terms (Moreno Reference Moreno2006). Spanish regions have a statute of autonomy and representative powers (executive and legislative) that are directly elected by universal suffrage.

We attributed the condition of native (local born) or parachutist to the MPs by comparing their autonomous community of birth with the autonomous community of their current constituency. If the two regions matched, the MP was considered a native. If the MP was born in a different autonomous community from that of his/her constituency, then the MP was considered to be a parachutist. Clearly, this definition presents serious limitations. It does not reflect the case, for instance, of MPs who were born in one autonomous community but raised in another. Information on the place of residence or the location of the primary–secondary school/university could have been collected too, but those data were very difficult to obtain in Spain (Latner and McGann Reference Latner and McGann2005; Pedersen, Kjaer, and Eliassen Reference Pedersen, Kjaer and Eliassen2007; Berry Reference Berry2013; Jakub Reference Jakub2017). Using the birthplace provides robust data, which are easier to collect and compare with data from other studies that have previously been conducted in Spain and elsewhere (Rodríguez-Teruel Reference Rodríguez-Teruel2011; Coller, Santana, and Jaime Reference Coller, Portillo, Domínguez, Escobar and García2018).

The analyses excluded deputies who were born abroad (2% of all MPs) due to the impossibility of comparing their place of birth and their constituency. Unlike France and the United Kingdom, Spain does not have “foreign constituencies” located in former colonies, so these foreign MPs would invariably be parachutists, wherever they were elected. To avoid this distortion, they were given a special treatment in our analysis. MPs elected in the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla were also excluded, because they only have one seat each. The small number of cases could have led to alterations compared to the other regions.

Results and Discussion

Native and Parachutist Candidates

We used a modified version of the Territorial Representation Index (TRI) to measure the degree to which each region’s territorial elites are represented in the Congress of Deputies. Originally designed by Cuenca and Miranda (Reference Cuenca and Miranda1987), the TRI compares the number of ministers by territory with the respective population. In this study, however, the index was calculated by dividing the percentage of representatives born in a territory (autonomous community) by the percentage of seats held by this territory in the Congress. The more proportional the territorial representation, the closer to 1 its index value. In the regions with a high proportion of native MPs, the value is above 1. In those with a low proportion of native MPs, the index value is below 1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Territorial Representation Index of the Congress of Deputies of Spain (1977–2020).

Source: Author’s own elaboration using the BAPOLCON database.

Figure 1 shows a historical disproportion among territories. Broadly speaking, the MPs born in the center and the north of the Spain have historically been overrepresented in the Congress of Deputies, while those born in the south, on the islands, and in the Mediterranean regions have been underrepresented. More precisely, the Canary Islands is the autonomous community that has had the lowest number of natives holding a seat in the Congreso (TRI = 0.81), followed by the southern Castile–La Mancha (0.85), Andalusia (0.9), Catalonia (0.89), and the Valencian Community (0.91) on the Mediterranean coast. At the other end of the spectrum, Cantabria has been the most overrepresented region in the lower house (TRI = 1.31), followed by Castile and León (1.12), Madrid (1.11), and the Basque Country (1.1). There are differences between underrepresented Catalans and overrepresented Basques. As will be shown later, the high proportion of MPs born in the Basque Country constitutes an exception among peripheral regions. It is also worth noting that Madrid has 10% more natives in the courts than would correspond to it in terms of seats. This finding seems to confirm the capital effect and its influence on the presence of native elites in central institutions.

Observing the historical evolution of the TRI by legislature (Table 1), the trends have remained stable, with some exceptions. Andalusia, the Canary Islands, and Castile–La Mancha are, along with Catalonia, the most underrepresented territories in the Congress based on the number of MPs born there. MPs born in Catalonia are slightly less underrepresented in the Congress from the sixth to the 12th legislature, with the exception of the last two, which began in 2019. The Basque Country remains an exception among the peripheral territories. The TRI was above 1 except in four legislatures, even exceeding a value of 1.2 in another four. Among the overrepresented regions, Madrid, Castile and León, together with Cantabria, stand out for their stability over time, with very high values in many legislatures. However, since 2015–2019, the trend has changed for those autonomous communities, which are now underrepresented. It is difficult to understand the reasons for this change in recent years, but worthy of note, it coincides with a party system transformation in Spain, characterized by the entry of new political parties and increased parliamentary fragmentation (Portillo-Pérez and Domínguez Reference Portillo-Pérez, Domínguez, Freire, Barragán, Coller, Lisi and Tsatsanis2020).

Table 1. Territorial Representation Index of the Congress of Deputies of Spain (1977–2020)

Source: Author’s own elaboration using the BAPOLCON database.

Note 1: Legislatures of the Congress of Deputies of Spain: Constituent (July 1977), I (March 1979), II (November 1982), III (July 1986), IV (November 1989), V (June 1993), VI (March 1996), VII (April 2000), VIII (April 2004), IX (April 2008), X (December 2011), XI (January 2015), XII (July 2016), XIII (May 2019), and XIV (December 2019).

Note 2: Average = 1; standard deviation = 0.12, and standard error = 0.03.

Territorial Origin of the MPs Representing the Peripheries and Madrid

To explain the imbalance among territories, it is necessary to delve into the mobility dynamics among constituencies. Figure 2 displays the proportion of native MPs who obtained a seat in their autonomous community (see also Tables A and B in the Online Appendix for the frequencies). As can be seen, the peripheral regions (the Canary Islands, Galicia, the Basque Country, Navarre, the Balearic Islands, the Valencian Community, Catalonia, Asturias, and Andalusia) are more likely to elect natives than the others. If we compare the number of native MPs in each autonomous community to the number of natives in the population of those territories (Table C and Figure A in the Online Appendix), the Balearic Islands (18%), Catalonia (12%), and the Basque Country (10%) stand out for having more natives among their MPs than in their population. Therefore, the native population of these communities is overrepresented in the seats that they elect to Congress. It seems that having a language of their own, or at least a different political–cultural reality, encourages the selection of candidates who are familiar with the local idiosyncrasy. The rest of the communities that elect a high percentage of natives to their seats have the same or somewhat higher percentages of natives in their population, with no overrepresentation of natives. The two variables, natives among the citizens and natives among MPs, do not present a statistically significant relationship.Footnote 3

Figure 2. Congress Seats Obtained in Each Territory by Native MPs (1977–2020) (%).

Source: Author’s own elaboration using the BAPOLCON database.

The autonomous communities with the lowest percentage of native MPs are those in central regions and Madrid. For the most part, their percentage of natives in parliamentary seats are lower than the percentage of natives in the citizenry, so natives in these territories are descriptively underrepresented. The electoral lists of these constituencies have a rather large number of MPs who were born elsewhere. In Madrid, half of the seats are occupied by deputies who were not born in the capital. This result is puzzling given that MPs who were born in Madrid are overrepresented in the Congress. It is reasonable, thus, to deduce that half of them win seats in Madrid, while the other half compete in the rest of the country.

Table 2 focuses on historical nationalities (Catalonia, Galicia, the Basque Country, and Andalusia) as well as Madrid, and illustrates the origin of the MPs who, without having been born in those territories, hold a seat there. In Catalonia, non-natives come from neighboring regions (such as Aragon and the Valencian Community) and from other areas with a long tradition of migrations (such as Andalusia) (García and Delgado Reference García and Delgado1988). In Madrid, as in Galicia and the Basque Country, MPs born in Castile and León represent a high percentage of non-natives who obtained a seat in those territories. As for Andalusia and the Basque Country, the high number of MPs from Madrid who win a seat there is striking. Finally, Galicia and the Basque Country, two territories with high emigration rates in the 20th century (Sallé Reference Sallé2009), have a high percentage of foreign-born MPs. This dynamic could be explained by the return of candidates born abroad.

Table 2. Autonomous Community (A.C.) of Birth and Election of Congress MPs (1977–2020) (%)

Source: Author’s own elaboration using the BAPOLCON database.

The Constituencies of the MPs Born in Peripheral Regions and Madrid

No direct relationship appears to exist between the proportion of native MPs born in a given region and those elected in another autonomous community. The trends, however, are very similar among territories. One exception is the Basque Country, which does not behave like the rest of the peripheries for this variable (Figure 3). The islands and the areas presenting cultural singularity have the lowest percentages of deputies elected from outside. Regarding the citizenry, in these peripheral autonomous communities, a low percentage of the native population has emigrated to other Spanish regions (Table D and Figure B in the Online Appendix). Nevertheless, the relationship between this value for deputies and that for the citizenry is not statistically significant.Footnote 4

Figure 3. Autonomous Community of Origin of Congress MPs Elected in Another Region (1977–2020) (%).

Source: Author’s own elaboration using the BAPOLCON database.

Conversely, more than half of the MPs born in Madrid obtained a seat outside the autonomous community (A.C.), which is 41 percentage points higher than the level at which the native population of Madrid resides in other autonomous communities. They are followed by the MPs born in Cantabria, La Rioja, and Castile and León, who exceed the 30% share of natives who obtained their seat in another autonomous community. As a national average, 24% of MPs have obtained their seat outside their native autonomous community, six points above the percentage of Spaniards living in a different autonomous community from the one in which they were born (18%). Therefore, the internal mobility of MPs between Spanish territories is somewhat greater than that of citizens.

Having determined the global percentage of native MPs who obtained their seat in a different region, Table 3 shows the specific dynamic of the MPs who were born in Andalusia, the Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia, and Madrid and elected in another autonomous community. Our aim was to analyze the destinations of the MPs born in these territories when they did not run for a seat in the electoral district in which they were born. As can be seen, Madrid has a huge power of attraction over the state peripheries since it constitutes the first recipient of non-native MPs. The reason is probably that, as the state’s capital, Madrid’s electoral lists have a special impact on public opinion, thus providing a suitable stage for MPs with a good position within the party and who seek visibility. On the one hand, more than a third (30–35%) of MPs who were born in Andalusia, Castile–La Mancha, Castile and León, the Canary Islands, Catalonia, Galicia, La Rioja, and the Basque Country have been elected in a Madrid constituency. On the other, MPs who were born in Madrid have usually been elected in Castile and León (22%), Castile–La Mancha (16%), Andalusia (14%), and the Valencian Community (13%). It is also interesting to note that native MP mobility is very low in the two territories governed by the strongest ethnonationalist parties, namely the Basque Country and Catalonia. Only 1% of Catalan-born MPs have been elected in the Basque country, and only 3% of Basque-born MPs have obtained a seat in Catalonia. However, Catalonia has been a well-established destination for Andalusian and Galician-born MPs (around 20%), reflecting a common internal migratory direction in the second half of the 20th century (García and Delgado Reference García and Delgado1988).

Table 3. Congress Seats Occupied by Native MPs From Five Regions Elected Outside (1977–2020) (%)

Source: Author’s own elaboration using the BAPOLCON database.

Abbreviation: A.C., autonomous community.

Although not visible in Table 3, it is worth noting that MPs born in other regions have usually won a seat in a neighboring territory. For example, MPs born in Valencia have usually been elected in Madrid (10%) or Catalonia (34%). Among the parliamentarians born in Extremadura, 42% have been elected in Andalusia. The Navarre-born members of Congress have been elected in the Basque Country (49%) and in Aragon (42%); the deputies from Aragon are also more likely to have been elected in Catalonia (43%). Those born in Murcia have mainly been elected in the Valencian Community (43%) and Andalusia (26%). Finally, Asturias-born MPs constitute the exception to this rule of geographical proximity, since 33% of them have been elected in Andalusia.

The Role of Political Parties

Drawing on Coller et al. (Reference Coller, Portillo, Domínguez, Escobar and García2018), it was hypothesized that region-wide parties, that is, those defending the interests of a substate territory, include more native MPs than state-wide parties. The prime reason is that those political formation parties are not under the tutelage of a general quarter located in Madrid (the state capital), imposing parachuted MPs on its local branches. In addition, some regional parties tend to recruit native MPs for their ability to speak the regional language. Moreover, regional parties have the promotion of regional (or national) identity on their agenda as opposed to a state identity. This highly explicit thematic axis in Catalonia and the Basque Country may also help to explain the large number of natives among their MPs. Although this is not always the case, intuitively, a nonnative may be regarded as less motivated in terms of identity to support issues (going on electoral lists) such as independence or the sovereignty agenda. Such statements have proven to be true. In Spain, these parties have recruited 16% more natives than state-wide parties. In Figure 4, we compare the percentage of native MPs elected in five regions and the Spanish average in political parties at the regional and state levels. As expected, Catalonia and the Basque Country have a higher percentage of natives than the Spanish average, mainly due to the influence of their region-wide parties (the percentage of natives in the state-wide parties in these two communities is very close to the average).

Figure 4. Congress seats held by native MPs in five autonomous communities (1977–2020) (%).

Source: Author’s own elaboration using the BAPOLCON database.

Note: * means that differences are statistically significant at 95% confidence intervals.

Although to a lesser extent than in Catalonia and the Basque Country, region-wide parties from the Canary Islands and Galicia also incorporate higher percentages of native MPs than the state-wide parties—3 and 7% more, respectively. The same could be said about the rest of the region-wide parties’ MPs who were elected in Andalusia, Aragon, the Valencian Community, and Asturias. Since 1977, these parties have been composed of a higher percentage of natives than the state-wide parties. One exception is Navarre, where region-wide parties include 2 percentage points fewer native MPs than the state parties.

The data in Table 4 indicate the percentages of native MPs according to the status of their respective parties: region or state-wide.Footnote 5 One can observe that left-wing region-wide parties in Catalonia and the Basque Country (Esquerra Republicana de Cataluña (ERC) and Abertzales) include the highest percentage of natives. It is also worth noting that the state-wide parties (PSOE, PP, and IU-Podemos) in these territories have very similar percentages of natives to that of the rest of Spain. To put it differently, the high percentage of native MPs in Catalonia and the Basque Country seems to be due to their towering presence in the autonomous parties, because state-wide parties have hardly increased the percentage of natives among their ranks in those autonomous communities.

Table 4. Congress Seats Held by Native MPs in the Main Parties of Five Autonomous Communities (A.C.s) (1977–2020) (%)

Source: Author’s own elaboration using the BAPOLCON database.

Note: Not all regional parties are listed here; the above were selected owing to their major presence throughout the 15 legislatures analyzed. The meanings of the parties’ acronyms can be found in endnote 5.

Table 4 also shows that Coalición Canaria (CC) exceeds the average share of native MPs in its region by more than 16 percentage points. However, in Galicia and Navarre, two parties with different ideologies, namely the Bloque Nacionalista Gallego (BNG) and the Unión del Pueblo Navarro (UPN), have fewer natives than the rest of the region and state-wide parties. A possible explanation could be that the BNG only obtained 3% of the seats elected in Galicia since 1977. In Navarre, the UPN obtained almost 20% of all seats, but its coalition with the Partido Popular—the main state-wide right-wing party in Spain—may have influenced its recruitment policy.

Finally, we calculated the TRI for each political party by dividing the number of native MPs by the number of corresponding seats in a given autonomous community. As a result, only the PSOE and the PP have maintained a mostly constant representation of native MPs throughout the Spanish regions (Table E in the Online Appendix shows the historical PP and PSOE TRI per autonomous community). Globally speaking, the PSOE tends to recruit its MPs from northern Spain: the Basque Country (TRI of 1.27), Cantabria (1.25), Castile and León (1.21), and Asturias (1.15) are overrepresented. In contrast, Socialist MPs born in the Mediterranean regions are underrepresented: Catalonia (0.85), the Balearic Islands (0.93), Murcia (0.96), and Andalusia (0.91)— with the exception of the Valencian Community (1.1). The native MPs of the PP are mainly present in Cantabria and the Basque Country, with a TRI of 1.42 and 1.34, respectively. The PP also overrepresents the MPs born in Madrid (1.33), confirming its importance as a recruitment hub for ministers (Rodríguez-Teruel Reference Rodríguez-Teruel2011, Reference Rodríguez-Teruel2013) and parliamentarians for the Conservatives.

The Parliamentary Hyper Elite

To complete the analysis of the territorial representation in the Congress of Deputies, we also analyzed the “hyper elite” within the lower chamber, that is, the roster of MPs belonging to the Permanent Deputation and the Board of Spokespersons (Santana, Aguilar, and Coller Reference Santana, Aguilar and Coller2016). MPs are selected for hyper-elite posts by the parliamentary group’s leadership from among its members without, a priori, taking into account a territorial balance. This lack of adjustment to a territorial balance regarding the origin of MPs helps us to analyze how parliamentary groups favor or disfavor the presence of MPs born in each territory.

Table 5 introduces the TRI for the hyper elite of the Congress. On the one hand, the percentage of seats occupied in the Permanent Delegation or on the Board of Spokespersons of the parliamentary groups by natives of each autonomous community is taken into account. This percentage is then divided by the percentage of seats that corresponds to those regions in the Congress of Deputies. These parliamentary bodies naturally have a clear political component and are not supposed to take the territorial balance into account when appointing MPs to these positions. However, our analysis provides relevant insights. Indeed, it allows us to confirm that the MPs born in Catalonia, the Valencian Community, the Canary Islands, the Balearic Islands, and Andalusia are also underrepresented in this body. Even Galicia—which is slightly overrepresented in the whole Congress—has fewer MPs in the hyper elite than it should, based on its corresponding seats. This peripheral nature diminishes the presence of these regions in the power center of the lower house. At the other end of the scale, Madrid, Castile and León, and “the Basque exception” are overrepresented. This complementary analysis confirms the closeness of those territorial elites with respect to the legislative power. The overall trend previously observed for Congress is, thus, largely consolidated by the hyper elite, for whom the political decision component is more discretionary, yet decisive, regarding the selection of MPs.

Table 5. Territorial Representation Index Applied to the Congress Hyper Elite (1977–2020) (%)

Source: Author’s own elaboration using the BAPOLCON database.

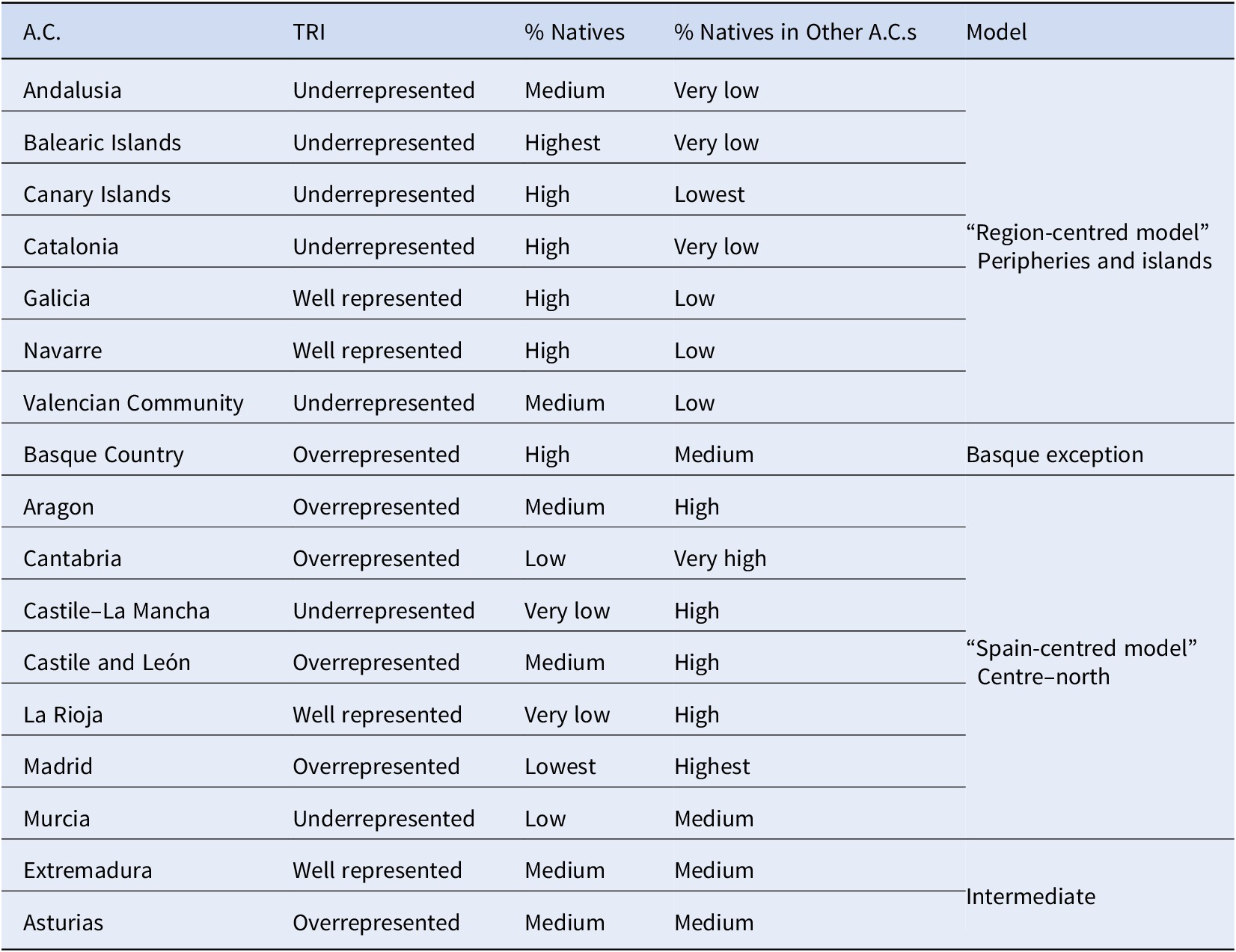

Models of MP Territorial Dynamics

Table 6 summarizes our findings and allows the classification of the territories in relation to the previously explored indicators. Four general models of territorial dynamics are identified. First, the “region-centered model” encompasses the islands (the Canary Islands and the Balearic Islands) and peripheral territories such as Catalonia, Galicia, Navarre, the Valencian Community, and Andalusia. These autonomous communities are characterized by constant underrepresentation in the Congress (fewer MPs born in those regions than seats) and in the hyper elite. They present high shares of natives, but their capacity to “export” MPs is limited, probably due to the considerable attraction of regional politics. These regions have a strongly politicized regional identity, which gives their MPs incentives to remain within these territories (Stolz Reference Stolz2003, 243).

Table 6. Territorial Dynamics Models According to Autonomous Community (A.C.)

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on the interpretation of the results.

Note: Values of categories: for the TRI, underrepresented (0.95 or less), well represented (from 0.96 to 1.04), and overrepresented (1.05 or more); for the percentage of natives, low (70 or less), medium (from 71 to 80), and high (more than 80); for the percentage of natives in other autonomous communities, low (19.9 or less), medium (from 20 to 27.5), and high (more than 27.5).

The second model is “Spain-centered” and incorporates Madrid, Castile–La Mancha, Castile and León, Cantabria, and La Rioja. This group corresponds to the central–northern parts of Spain. Those regions are overrepresented owing to their great capacity to “export” MPs and despite the limited presence of native MPs occupying their seats in the Congress. However, Madrid, Cantabria, La Rioja, and Castile and León are also among the most overrepresented regions in the hyper elite. Such extensive mobility is especially significant in Madrid; only half of those having obtained a seat in Madrid were born there (the capital effect). However, MPs from Madrid are overrepresented in the chamber thanks to the large number of Madrid-born MPs who have won a seat elsewhere. Lying between these two models is the intermediate model, which refers to autonomous communities (Extremadura and Asturias) that are well represented and account for average numbers of MPs, both native and from other autonomous communities.

The Basque Country model is an exception because, unlike other peripheral autonomous communities, it is overrepresented in the Congreso de Diputados. This situation is due to a large number of native MPs being elected in the three Basque constituencies—as in the “region-centered” model. However, the Basque Country also accumulates a high average percentage of Basque-born MPs elected in other territories, mostly in Madrid but also in La Rioja, Andalusia, or Castile and León—as in the “Spain-centered” model. Accordingly, this region is also overrepresented among the hyper elite.

Conclusion

This descriptive study analyzed the territorial representation of MPs and the effects of MP mobility in the Spanish Congress of Deputies. Based on the descriptive representation of Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) and using a modified version of the Territorial Representation Index (TRI) (Cuenca and Miranda Reference Cuenca and Miranda1987), MPs’ autonomous communities of birth were taken as a reference and compared with: the autonomous communities in which they were elected; the number of seats in Congress associated with each autonomous community (size); the roles of the parties; and how territorial inequalities were reflected in the parliamentary hyper elite. As a result, it was found that, despite legislative efforts to maintain a balanced geographical representation, MP mobility generates imbalances that persist over time. Specifically, some autonomous communities (Andalusia, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Catalonia, the Valencian Community, and Castile–La Mancha) are historically underrepresented while others are well represented (Galicia, Navarre, La Rioja, and Extremadura) or overrepresented (Aragon, Cantabria, Asturias, Castile and León, and Murcia). Moreover, there are some special cases of overrepresentation, such as Madrid (the capital effect) and the Basque Country, which are exporters of native MPs to other autonomous communities. It was not the aim of this article to explain why MPs move, but it was found, nevertheless, that mobility is not a simple reflection of population movement. MPs have their own dynamics as their movements are not statistically significantly correlated with the migration dynamics of citizens. The results for Spain corroborate findings in the literature according to which native MPs from central regions and Madrid are overrepresented (Latner and McGann Reference Latner and McGann2005; Berry Reference Berry2013; Jakub Reference Jakub2017). Moreover, it could be observed that the attractiveness of territorial politics in the peripheries (Stolz Reference Stolz2003; Dodeigne Reference Dodeigne2018) may be one of the reasons why native MPs in these territories do not stand for election in other constituencies (except for the Basque Country).

This under- and overrepresentation were also reflected in the hyper elite, a power and decision-making body, which curiously does not have any measure to guarantee territorial proportionality (see Table 5). The dynamics additionally occur at the party level, and become party selection strategies: it is common for region-wide parties to have more natives than state-wide parties, especially in the peripheries, where the number of natives is greater (greater cultural identification) (see Figure 4 and Table 4). These dynamics give rise to the four general models explained in the present article (see Table 6): the region-centered model—coinciding with the peripheries and the islands; the Spain-centered model (center–north); the intermediate model; and, lastly, the Basque exception model.

Overall, this preliminary study presents a number of limitations. Taking MPs’ birthplace into consideration may be a relevant—although imperfect—indicator of the evolution of the territorial representation. However, it is necessary to further investigate the individual roles of MPs with respect to their territory of reference (through their local, regional, or state orientation) in order to better understand the representation and political implications of MP mobility. Consequently, although the present work is a first step and opens the debate on the territorial representation of the legislative branch, further studies—with a broader scope—need to follow.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Xavier Coller, co-owner of the BAPOLCON database, for his generous provision of the database. They also thank the hard-working team of Nationalities Papers for their support during the COVID-19 pandemic and especially the reviewers, who greatly contributed to improving the contents of the manuscript. Finally, the authors thank Jean-Baptiste Harguindéguy and Giulia Sandri for their recommendations and revisions throughout the writing of this study.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2022.6.

Financial Support

The authors are currently employed under a predoctoral contract at the Pablo de Olavide University, funded by the State Research Agency of the Spanish government (BES-2017-081555 and FPU16/02601). The updating of the BAPOLCON database was conducted during the research project: CIUPARCRI “Ciudadanía y parlamentarios en tiempos de crisis y renovación democrática: El caso comparado de España en el contexto del sur de Europa” (CSO2016-78016-R) funded since 2016 by the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Empresa (Ministry of Economy and Enterprise). The authors also thank the Department of Sociology of the Pablo de Olavide University for financially supporting the linguistic revision of the English version of this article.

Disclosures

None.