Among the many cases of democratic decline that have attracted the attention of scholars in recent years, a handful stand out for the peculiar and protracted means by which elected leaders have methodically subverted democratic institutions. In contrast to breakdowns such as the iconic military coups of the 1970s, these recent cases exhibit a gradual process of erosion, in which incumbents attack institutions iteratively, at the margins, and with the cover of legitimacy conferred by elections. In countries as far afield as Venezuela, Turkey, and Thailand, democratically elected leaders have challenged political rights and freedoms, repealed term limits, attacked the press, restricted or closed legislatures, packed courts or removed judges, asserted personal control over state bureaucracies, jailed political opponents, and persecuted opposition parties. Bermeo (Reference Bermeo2016) calls this process “executive aggrandizement,” which she distinguishes from other types of democratic erosion or breakdown like military coups, “executive coups” like Fujimori’s autogolpe, or various forms of electoral manipulation. Bermeo and other scholars note that aggrandizement has been frequent in recent decades and is a common feature in cases of democratic backsliding (see also Lührmann and Lindberg 2019, Kaufman and Haggard Reference Kaufman and Haggard2019; Svolik Reference Svolik2019; Waldner and Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018). Yet the literature has not developed a comprehensive explanation of how aggrandizement unfolds.

A proper understanding of regime dynamics in fragile democracies requires analysis of a broad range of outcomes. The literature’s disproportionate focus on cases like Turkey and Venezuela, in which incumbents have successfully established authoritarian regimes, has produced an incomplete picture of the process of aggrandizement, and has led scholars to overestimate the likelihood of democratic breakdown (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016, 6; Schedler Reference Schedler2019). We illustrate this point by analyzing cases in which democratic institutions survive aggrandizement, in addition to those that result in democratic breakdown either because the incumbent consolidates power or is removed from office by nondemocratic means.

Our approach generates insight about regime outcomes by analyzing the complex strategic environment that aggrandizement creates for the incumbent and opposition actors. Drawing inspiration from O’Donnell and Schmitter (Reference O’Donnell and Schmitte r1986), we conceive of the initial challenge to the institutional status quo as the start of a “critical period,” during which incumbents and opposition actors face strategic dilemmas in repeated interactions while operating under significant uncertainty (see also Bernard Reference Bernhard2015; Capoccia Reference Capoccia2005, esp. 16; Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñan Reference Scott and Pérez-Liñán2013). Writing in the same context, Gamboa (Reference Gamboa2017) demonstrates that the reaction of opposition actorsFootnote 1 to aggrandizement was especially critical to the survival of democracy in Colombia, and democratic collapse in Venezuela. We slightly modify Gamboa’s framework and demonstrate that her insights can also help to explain a more diverse set of cases. While incumbent actions are always instrumental in democratic breakdowns of this kind (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018), we also find that the opposition’s aggressive tactics exacerbated breakdowns in Turkey, Venezuela, and Thailand, while the more moderate approach of opposition actors in Ecuador and Bolivia (until recently) helped to sustain democratic institutions. We also explore how institutional factors and the progression of time affect the calculations of many opposition actors. We show that uncertainty tends to generate cautious behavior initially, but that incentives for continued moderation decrease over time, making democratic breakdown more likely.

Explaining the Consequences of Aggrandizement

Our overarching goal is to explain why aggrandizement results in one of three distinct regime outcomes. The first is an incumbent takeover, in which the incumbent’s gradual consolidation of power results in an authoritarian regime. In our view, incumbent takeover requires a certain level of institutionalization, such as the implementation of a new, non-democratic constitution, or the decisive removal of term limits, which are an important bulwark against the personalization of power in new or weak democracies (Corrales Reference Corrales2018, esp. ch. 8). The incumbent may also establish control over the state bureaucracy to such an extent that executive mandates outweigh constitutional principles, and this consolidation of power manifests in such actions as blatant political repression, the imprisonment of journalists and opposition politicians, or the nullification of inconvenient electoral results. Compared to related concepts such as “competitive authoritarianism” (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002, Levitsky and Loxton Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013), which is based primarily on the lack of fairness in electoral processes, our understanding of incumbent takeover implies a stricter threshold for labeling a country as authoritarian, based on a determination that democratic institutions are decisively broken.

The second possible outcome of aggrandizement is incumbent removal. In these cases aggrandizement deepens into a regime crisis, but in contrast to incumbent takeovers, the executive is removed from office via the extra-constitutional intervention of another actor. Most commonly we would expect this actor to be the military, but in principle crises of this kind might also be resolved by a rebellion, the intervention of a foreign power, or some other means. We also conceive of these cases as instances of democratic breakdown, because of the extra-ordinary means by which the incumbent is removed and the resulting uncertainty about the sanctity of electoral institutions moving forward. In principle, incumbent removals might lead to rapid redemocratization, as posited by Linz’s (Reference Linz1978) discussion of reequilibration or by the idea of “promissory coups” (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016). But in practice, incumbent removals rarely generate improved democratic outcomes even when they have a plausible democratic justification, as our discussion of the Thai and Bolivian cases illustrates.

The third possibility is democratic survival. Aggrandizement is a form of democratic erosion, and therefore it weakens democratic institutions by definition. Actions such as challenging political rights and freedoms, attacking coequal branches of government, or undermining electoral processes have real consequences. However, countervailing institutions are often resilient, and erosion may fall short of an authoritarian institutional restructuring. Aggrandizing incumbents may fail in their attempts to remove core constitutional guarantees of power-sharing and alternation, to personalize the state bureaucracy, or to bring the national judiciary to heel. Space for dissent, organization, and electoral competition may remain open, even if it is restricted. And in cases that we identify as democratic survival, the incumbent is eventually replaced through normal democratic procedures (typically, a national election).

The literature has not developed a clear explanation of these distinct outcomes because it has focused primarily on the actions of incumbents in cases of incumbent takeover (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Waldner and Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018, 16; Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016, 11-12). These studies, not to mention the common depiction of such leaders as omnipotent “strongmen” in scholarly and journalistic accounts, suggest an executive-centric understanding of aggrandizement and its consequences. This focus is warranted to a point—the personal charisma and leadership, the intense authoritarian ambition, and perhaps the luck of leaders like Hugo Chávez and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan were obviously instrumental to democratic breakdown as it happened in Venezuela and Turkey. Nevertheless, we argue that the actions of incumbents do not uniquely determine outcomes. Presidents are rarely as powerful as the literature portrays them. Opposition behavior matters too, and outcomes are a function of repeated interactions, gambles, guesses, and choices made by both incumbents and opposition actors in the indeterminate environment of critical periods. Our conceptual framework allows us to analyze the strategic choices of key political actors, whose behavior may be constrained by cognitive or normative biases, but who have broad latitude to act within structural and institutional constraints.

Our analysis begins where one or more actors perceives a substantial challenge to the institutional status quo, and we view this challenge as a struggle for power. Incumbents aim to protect their tenure in office, to press any advantages in power that they perceive, and to undermine constraints on their power, though they may not initially intend to upend democratic institutions. Opposition actors—by which we mean not only an electoral opposition but also organized civic groups like unions, religious organizations, or business groups, and even institutions like legislatures, when they are controlled by actors who oppose the incumbent and act in unison—aim to limit these maneuvers. We assume that these actors initially favor the status quo democratic institutions as a means of constraining the executive, though events may lead them to question this preference over time. Initially, both sides may be constrained by democratic institutions, not only because institutions limit power, but also because there are gains to be had from cooperation. Yet as we will see, the institutional challenge suggests that the democratic equilibrium is under threat.

The Role of Uncertainty

The critical periods that we analyze here are characterized by fundamental uncertainties about the basic rules of the game, the intentions of other actors, and the balance of power between the executive and the opposition. O’Donnell and Schmitter (Reference O’Donnell and Schmitte r1986) most famously brought these ideas to the study of democratization, and many other scholars have expanded on their insights. Schedler (Reference Schedler2013) argues that authoritarian leaders are particularly vulnerable to uncertainty because their opponents are more likely to withhold information or to conceal behavior. Weak democracies with aggrandizing executives are not (yet) authoritarian regimes, but incumbents and opposition actors face heightened uncertainty for similar reasons. In presidential democracies, the uncertainty caused by “outsider” candidates (Linz Reference Linz, Linz and Valenzuela1994) and “inchoate” party systems (Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995) “is not limited to outcomes … there is also more uncertainty about who the players will be” (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2018, 75). These conditions can lead to democratic instability because they fail to structure electoral competition in ways that create stable expectations and widespread agreement about the democratic compact. Scholars of Middle Eastern politics have identified a similar source of uncertainty caused by the dubious democratic commitments of the rising Islamist opposition movements (Lust Reference Lust2011).

Most countries that experience aggrandizement, including all of the cases we analyze in this article, have already experienced a political shock like the breakdown of the party system or the electoral victory of an outsider candidate. Helmke (Reference Helmke2017) analyzes imbalances that may exist between an outsider president’s formal constitutional powers and her level of partisan support (in congress or among the public), and shows that uncertainty regarding these imbalances can precipitate institutional crises such as those we study here. For example, a president who is constitutionally strong but politically weak may use formal powers to sidestep or undermine other branches and institutions. In other words, aggrandizement can result when incumbents perceive themselves to be in a weak position and are suspicious of other actors’ commitment to democratic institutions. Presidents who do this may not intend to undermine democracy (Helmke Reference Helmke2017, 14, 102). But they must take “a calculated risk. And precisely because presidents are unable to perfectly gauge the point at which exerting their power triggers legislative sanctions, presidents … sometimes push the envelope too far” (Helmke Reference Helmke2017, 12).

Aggrandizing executives do not know exactly how committed opposition actors are to democratic institutions, either normatively or instrumentally. Nor do they know how provoked they will feel, nor how unified they will remain, in response to initial attempts to aggrandize. Executives may act when they perceive even a temporary advantage in the balance of power, as Waldner and Lust (Reference Waldner and Lust2018, 16) argue. But their perception might be wrong, and their attempts to consolidate power may backfire. These various forms of uncertainty, in addition to the possibility that they may actually be playing a weak hand in some cases, leads us to predict the sequential nature of aggrandizement and the gradual pace of change at the beginning of the critical period.

The Opposition’s Strategic Dilemma: Responding to Aggrandizement

Uncertainty also affects the behavior of opposition actors, which may include political parties, the press, business groups, organized social groups like unions, parties, or religious organizations, or institutions like the legislature in certain situations. Take for example a case in which the executive uses decree power to bypass legislative resistance on a particular issue. Parties in the legislature, and other groups that oppose the incumbent, must decide if this move is the first attempted step in a broader effort to sideline the legislature entirely. If they mistakenly decide that it is not, then they may later regret not taking a stand against the encroaching executive. But if opposition groups mistakenly decide that the action is a threat (when it is not) and respond to it, they could suffer a range of consequences, from wasting scarce resources to provoking additional aggrandizement. In the cases we study here, uncertainty about the executive’s intentions and long-term strategy is severe. The strategic difficulties of various opposition actors are further compounded by their heterogeneity—they have different goals, organizational capacities, and levels of information, which may make it difficult for them to maintain cohesion and to act collectively.

Additionally, all of the countries we study here are weak democracies, which implies that the democratic commitments of powerful actors are conditional and subject to change based on their perceptions of what other actors are doing. Typically, the executive challenge creates the initial threat to democracy, and it forces opposition actors into a difficult strategic choice. Gamboa (Reference Gamboa2017) characterizes possible opposition responses according to their goals and strategies. Goals can be radical or moderate. “Radical goals … aim to end [the] presidency before the end of his constitutional term, while moderate goals … [aim merely to] thwart the president’s project.” Strategies can be “institutional,” such as using courts or elections, or “extra-institutional,” such as coups, violence, or boycotts (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017, 462; see also Cannon Reference Cannon2014). Gamboa further suggests that “individually, neither radical goals nor extra-institutional strategies contribute to democratic erosion. Together, however, [they] can have negative consequences” (2017, 462). In contrast, we believe that some “institutional” strategies can still damage democracy if they are unconventionally used to remove incumbents, and so we offer a slightly simpler conceptualization of opposition behavior along a single dimension. Most simply stated, the opposition can work to limit the extent of the executive’s encroachments and buy time for the next election, by which time the incumbent may be in a weaker electoral position for any number of reasons, or it can pursue a more aggressive attack against the incumbent’s power by trying to remove her from office before the end of the term. We refer to these two responses as moderate and radical.

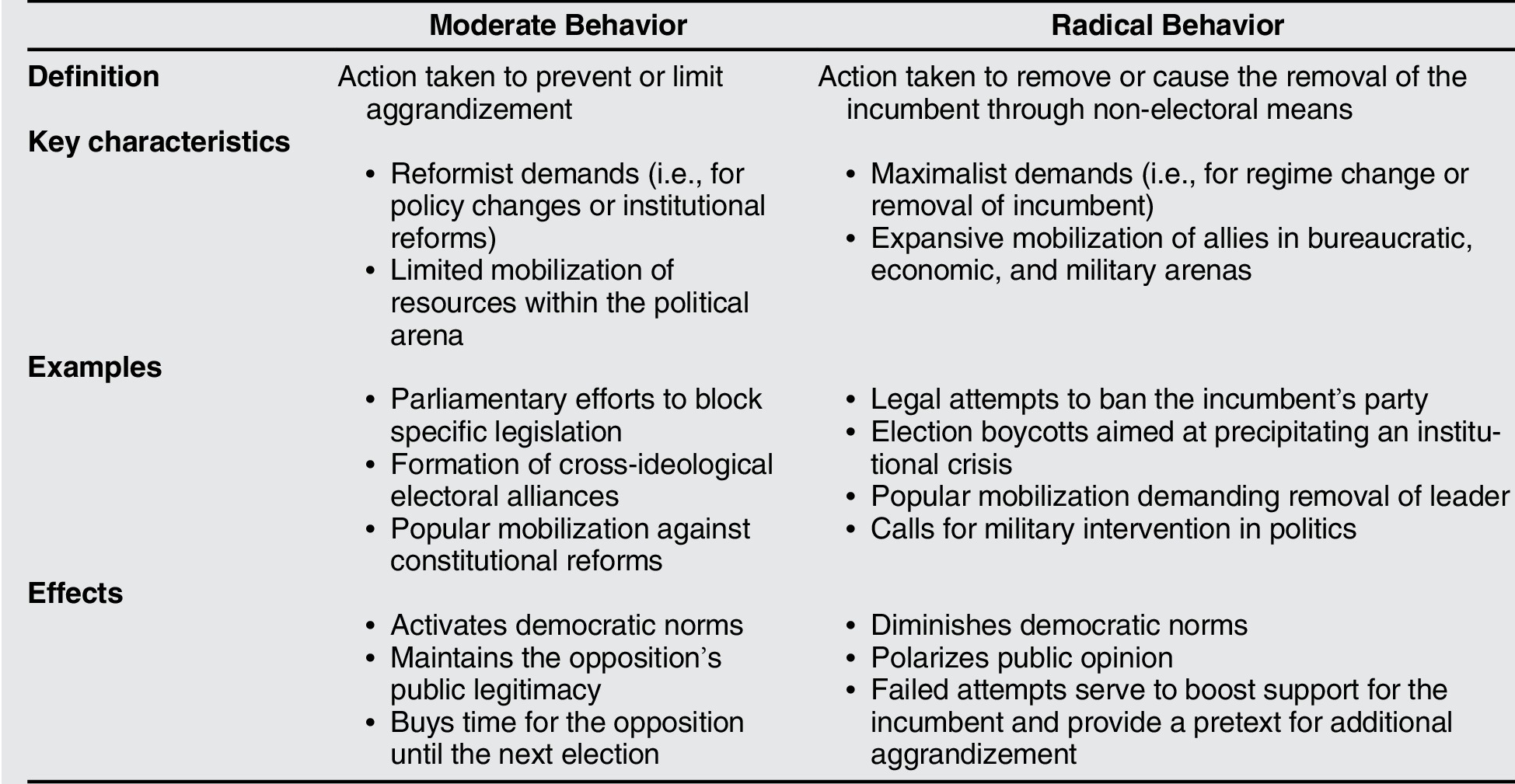

Moderate opposition behavior is focused on reversing or limiting the incumbent’s particular act of aggrandizement. It is framed as a dispute of law and policy rather than a rejection of the electoral legitimacy of the incumbent. Radical opposition behavior, on the other hand, is built on the demand that the incumbent resign or be immediately removed from power, using extra-institutional means if necessary. This demand is expressed through opposition leaders’ speech and their disengagement with the incumbent. Radical opposition behavior is expansive, in the sense that opposition leaders invoke help from “non-political” sectors, such as the military, bureaucratic, or economic elite. The goal is to mobilize all possible resources to force the incumbent to resign. Moderate opposition behavior, on the other hand, is strategically limited to the political arena, which conventionally carries a democratic legitimacy. We illustrate the main differences between moderate and radical opposition behavior in table 1. Our usage substantially overlaps with Gamboa’s (Reference Gamboa2017), with minor differences that we have described.

Table 1 Moderate and radical responses to aggrandizement

Most forms of opposition behavior fall squarely at one end of this dimension or the other. Electoral campaigning, lobbying, and political organizing are all moderate. Coup attempts and violent insurrection are categorically radical. Yet in some cases, neither the “institutionality” of the behavior nor its exact form is sufficient for categorizing the action as moderate or radical. In these cases, context matters. A public protest against a particular presidential decree, or a pre-election protest calling for the inclusion of a particular political party, is relatively moderate (see Schedler Reference Schedler and Lindberg2009, Reference Schedler2013). A protest calling for the military to depose the incumbent is decidedly radical. Similarly, an economic boycott organized around specific policy demands is moderate, but if the stated intention of organizers is to force the resignation or removal of the incumbent, this is more radical. There are even relatively moderate and radical means of pursuing political battles through the judiciary: challenging an executive order in the courts is a moderate action; attempting to use allies within the judiciary to outlaw the incumbent’s political party or remove the incumbent from office, is radical. In these examples, the ambiguity lies in the fact that not all protests (or boycotts, or court cases) are the same. But our criteria for determining whether opposition behavior is moderate or radical are consistent and objective, based on whether the explicit goal of the behavior, as revealed in the statements and actions of opposition leaders, is to prevent a specific act of aggrandizement and constrain the incumbent, or to remove her.

Opposition actors need to weigh the risks and benefits of these different options. Moderation offers certain advantages (see also Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017). A public commitment to democratic institutions is usually important for maintaining support beyond the partisan base. Moderation also buys time, so it should be an attractive option whenever the opposition perceives that the executive’s encroachments will be limited, or slow. Especially during the first term of an aggrandizing executive, opposition groups tend to focus on the next election as the most reasonable opportunity to remove the incumbent. At the same time, moderation entails certain risks. Even if particular institutional attacks seem minor, repeated attacks can add up, to the point that the opposition effectively forfeits the democratic bargain without even putting up a fight. Similarly, opposition actors may fear that moderation will encourage further aggrandizement. Radical responses to aggrandizement, on the other hand, are no panacea. Typically, any particular opposition actor would not be able to win an extra-institutional challenge to incumbent rule on its own. It could enlist the help of the military (or some other third party) in the hopes that the military would quickly re-establish civilian rule after intervening (Linz Reference Linz1978; Kinney Reference Kinney2019). Some opposition actors might even prefer the non-democratic rule of the military to the non-democratic rule of the incumbent. But asking the military to intervene is a risky proposition, and opposition actors would typically have limited capacity to influence or predict regime developments after a military intervention.

Iterated Behavior over Time and Predicted Outcomes

A key characteristic of critical periods is that the incumbent and opposition interact repeatedly, in an iterated fashion with no commonly known endpoint. For convenience, we can describe these interactions as though they take place in an alternating fashion: in each stage, the executive decides whether to challenge the institutional status quo “a little bit more,” and the opposition decides how to respond. In reality, the timing may be more complicated, distinct opposition actors may act at different times, and the executive may not be the first mover.

While we do not believe that incumbents and opposition actors always aim for proportional responses to each other, we do expect them to act cautiously at first, especially during the first term of an aggrandizing incumbent. This is because radicalism runs the risk of democratic breakdown, and will usually appear disproportional to the initial encroachments of the executive. Even if some opposition actors perceive a dire threat to democracy, it will be difficult to generate consensus among the opposition. Opposition groups may also judge that the initial election victory of the incumbent was an aberration, unlikely to be repeated. If these actors believe there is a strong chance to vote out the incumbent in the next election, they will remain moderate. Therefore, we expect that the opposition will usually meet early encroachments with an appeal to democratic institutions—perhaps rhetorical, as in public statements about the dangers inherent in the executive’s behavior, or perhaps more pragmatic, as in an appeal to the judiciary to protect a legislative prerogative. We expect this to be true even where there is variation in the degree of aggrandizement.

Yet the relative power of the opposition decreases with each successful encroachment by the executive, and thus the opposition’s ideal strategy may change over time. Once the executive usurps a particular power, closes a newspaper, or dismantles a political party, those changes are likely to stick. Even if some of the executive’s attempts fail, our baseline expectation is a rachet effect—a steady accretion of power to the incumbent (see also Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017; Waldner and Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018). Therefore we expect the aftermath of the incumbent’s second election to be an especially fragile point for democratic institutions. Not all opposition groups are actively involved in electoral contestation, and some groups will favor moderate (or radical) tactics regardless of the electoral calendar. Still, if the second election ends with the decisive victory of the incumbent, even election-minded opposition actors may reconsider their reliance on electoral mechanisms, and the prospects of waiting an entire electoral cycle for another opportunity may prove daunting, especially if they anticipate continued aggrandizement throughout the second term. Thus, we expect irregular attempts to remove incumbents to be more likely just after an electoral defeat, especially in the second electoral cycle or beyond.

The decisions opposition groups make at these critical moments are causally related to the different outcomes we have described. Moderate opposition behaviors are supportive of democratic institutions, and are thus more likely (though not certain) to result in democratic survival. Moderation signals support for democratic norms and institutions and makes it harder for the incumbent to justify a large-scale institutional transformation to concentrate executive power. Furthermore, working within democratic institutions may discourage further encroachments by de-escalating tensions with the executive and other political elites. On the other hand, we argue that radical opposition behavior significantly increases the risk of democratic breakdown. Radical responses to aggrandizement that fail to remove the incumbent can exact reputational costs as well as the loss of public support, the time and energy of opposition organizations, or even access to state resources (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017). They also provide the incumbent with the opportunity to paint his opponents as being hostile to democracy and to generate anger towards them, which helps the incumbent build mass support for his authoritarian agenda (Laebens and Öztürk 2020, 25; Öztürk Reference Öztürk2020, ch. 2). Even the cases in which radical attempts to remove an incumbent succeed, they can still lead to democratic breakdown, because the removal of a popularly elected incumbent by force typically creates severe institutional damage and can deepen political cleavages, leading to polarization and long-term instability (Linz Reference Linz1978, ch. 5).

Empirical Analysis

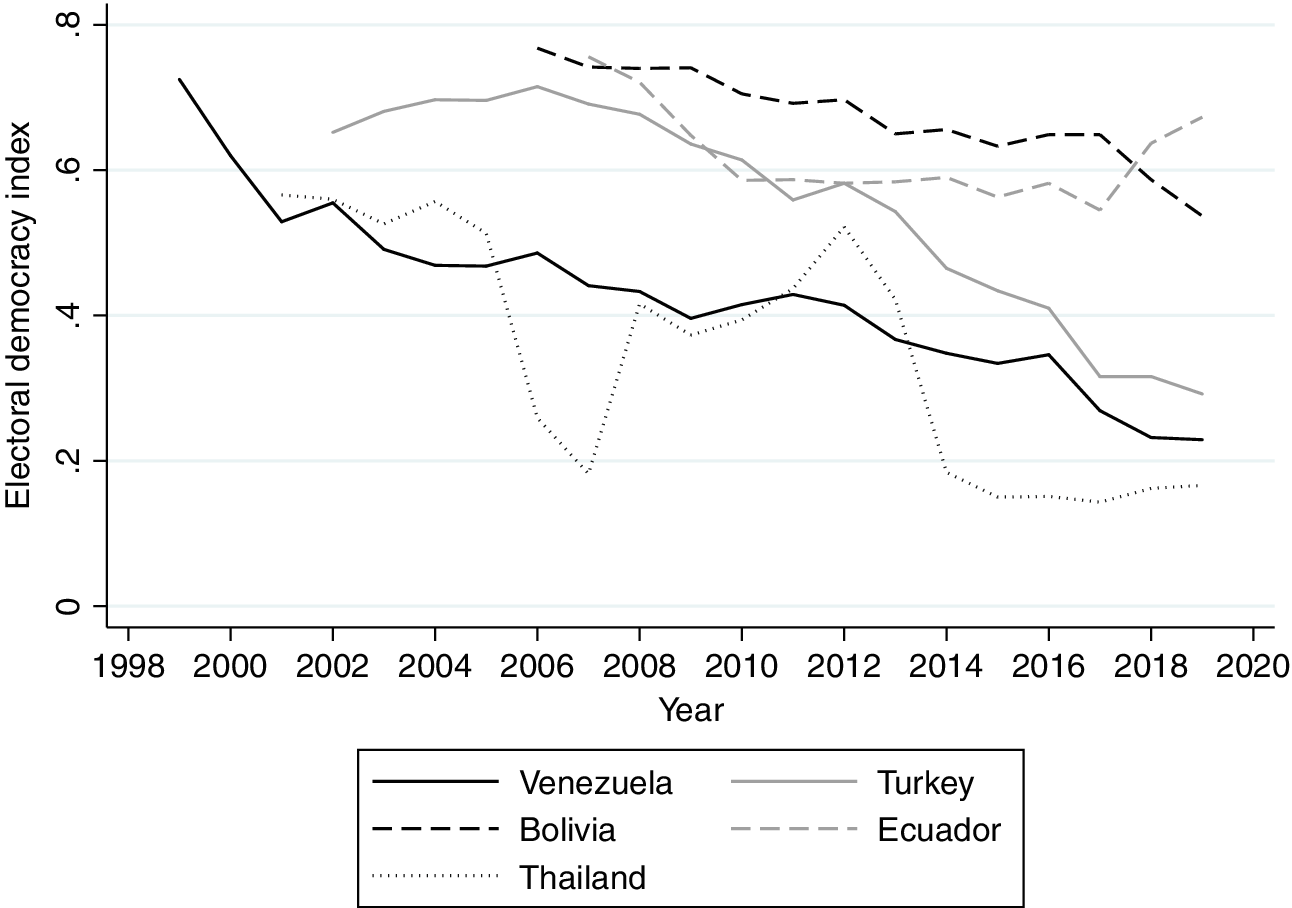

Our empirical goals are both descriptive and analytical. Descriptively, we document variation in regime outcomes among cases of aggrandizement and we elucidate the strategic environment that exists during the critical periods that aggrandizement creates. Analytically, we aim to understand how political actors respond to this strategic environment, and we offer preliminary tests of our hypotheses regarding the timing of changes in opposition behavior and the effect of opposition behavior on regime outcomes. All our cases begin with the election of an outsider candidate (or party) to office, and end for reasons that we will discuss. Two cases resulted in incumbent takeover (Venezuela under Chávez, 1999–2009, and Turkey under Erdoğan, 2002–2017), one is of incumbent removal (Thailand under Thaksin Shinawatra, 2001–2006), and one is of democratic survival (Ecuador under Rafael Correa, 2007–2017). We treat Bolivia under Evo Morales (2006–2019) separately, as a case in which democracy survived repeated aggrandizement for many years, but which ultimately resulted in an incumbent removal after the 2019 election. In figure 1, we show the value of the V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index for each of these five countries, from the start of the critical period through 2019.

Figure 1 Democratic backsliding and breakdown in five countries

Source: V-Dem version 10.

Our analytical efforts are based on structured comparisons of these five cases (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005). This case selection strategy helps to control for many institutional and structural factors that would otherwise need to be analyzed directly (refer to Part A of our online appendix for a detailed discussion). We analyze our cases in two stages. First, we explore the early years of the critical period, which typically run to the end of the incumbent’s first term. We show that, as expected, opposition groups tend towards moderate responses to executive encroachments, such as a focus on electoral mechanisms of influence and an appeal to horizontal accountability. The second stage of our analysis examines the divergence in opposition behavior that tends to occur after the second election (and sometimes later). We show that opposition actors are more radical after the second major elections in Venezuela, Turkey, and Thailand, and we discuss the changing strategic environments that led opposition actors to reevaluate their options during this period. In Bolivia and Ecuador, opposition groups remained mostly moderate during the second and third terms, until actors in both countries had to confront the decisive question of term limits for the sitting incumbent. In Ecuador, Correa backed away from trying for a fourth term, but just barely. In Bolivia, Morales’s successful effort to overturn term limits, even after they had been affirmed by a national referendum, eventually precipitated the crisis around the 2019 election. We have summarized our comparative framework and the most salient details of the five cases in table 2.

Table 2 Analytical summary of five case studies

Note: * We list the start of the three Latin American cases according to the date the presidents were inaugurated, even though they were actually elected late in the prior calendar year.

** In these two cases, executive aggrandizement continued, but did not trigger radical opposition responses.

Uncertainty and Moderation in Early Critical Periods

We have argued that pervasive uncertainty at the start of critical periods tends to push opposition actors toward moderation, because it is hard to assess the executive’s intentions, because they may not be able to build consensus for more radical actions, and because the subsequent election initially appears to be the best option for ousting the executive from power. Executives also tend to act with relative caution, even as they pursue aggrandizement, because of their own set of uncertainties.

Turkey clearly illustrates this dynamic. Mutual suspicion between the Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AKP) and secular institutions was well entrenched even prior to the 2002 elections. Secularists had long distrusted the democratic commitments of Islamist parties like the AKP and could point to anti-democratic rhetoric to justify their suspicions. For example, in 1996 Erdoğan had famously said that “democracy is like a streetcar. When you come to your stop, you get off” (Sontag Reference Sontag2003).Footnote 2 With that sort of history and the perception of Islamist parties as a threat to the constitutional order, secular parties perceived Erdoğan’s electoral victory as a significant crisis. In response, Erdoğan and the AKP acted with considerable caution. During the campaign, they repeatedly announced that they had no intentions of changing the constitutional regime if they were elected. After the election, they refrained from pursuing any significant constitutional changes to avoid conflict with opposition forces, even though they held a supermajority in parliament. The AKP government recognized that opposition actors could perceive even moderate proposals as potential attacks on democracy.

At the same time, powerful opposition actors generally stayed within the bounds of democratic institutions when devising strategies to oppose Erdoğan and the AKP majority. This is not because more radical reactions were somehow unthinkable or “off the table.” Indeed, public rumors about a military intervention emerged and clandestine debates about intervention were happening (Balbay Reference Balbay2003; Yalman Reference Yalman2014, 274, 463). Leaked minutes of a top-secret meeting attended by all four-star Turkish generals in December 2003 indicate the precariousness of the situation (Berkan Reference Berkan2011, 60-67; Örnek Reference Örnek2014, 207-216).Footnote 3 The generals were afraid that the AKP would use its electoral power to dismantle the constitution, but they could not agree on the appropriate way to respond. Only twenty days after this meeting, in an attempt to discern Erdoğan’s motives, the generals invited him to a special “briefing,” at which they explicitly asked him to explain what “democracy is like a streetcar” meant (Berkan Reference Berkan2011, 64; Yalman Reference Yalman2014, 274). A coup did not materialize because hardliners were unable to convince more moderate officers to join them, and they were not sure whether civil society and the general public would support them. Instead, civilian and military opposition groups remained cautious, and focused their attention on the 2007 elections.

The Thai case also illustrates a high degree of uncertainty and a tendency towards moderation during Thaksin’s first term. Indeed, speaking of his political future just two months after taking office, and already facing a (preexisting) corruption trial, Thaksin reflected that “only uncertainty is certain” (Mydans Reference Mydans2001). The court case had been filed prior to the 2001 election, based on an investigation of Thaksin’s personal finances while he was a deputy prime minister in the late 1990s. As it happened, he was acquitted by the Supreme Court with only a one-vote margin, but civic organizations continued to accuse him of corruption even after his acquittal (Phongpaichit and Baker Reference Phongpaichit and Baker2009, 65). Even though his party controlled the executive and legislative branches, Thaksin perceived himself to be in a weak position, and he feared that his opponents would be able to destabilize his rule (Hewison Reference Hewison2010, 127). He responded with efforts to undermine organizations that opposed him, and he warned judicial institutions “not to be too independent” (Phongpaichit and Baker Reference Phongpaichit and Baker2009, 173). Yet for the most part, Thaksin’s moves against opposition groups and democratic institutions in 2002 were cautious. For example, in separate incidents, his administration dropped money-laundering investigations against oppositional civil society organizations and journalists, and withdrew a proposal to establish an “ethics oversight board” to monitor the media, after harsh public reactions (Phongpaichit and Baker Reference Phongpaichit and Baker2009, 153).

Most opposition groups also acted with moderation in the years after the 2001 election. Their main aim was to oppose Thaksin on policy rather than undermining his incumbency (Sinpeng Reference Sinpeng2013, 144). As the 2005 election approached, most opposition movements focused on electoral forms of opposition, such as tactical voting against Thaksin’s party, even when that meant supporting the relatively conservative Democrat Party. In fact, the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), whose “yellow shirts” would later be so closely associated with the protests that led to the coup against Thaksin, was founded in late 2004 for the explicit purpose of creating an electoral counterweight to Thaksin’s coalition (Kitirianglarp and Hewison Reference Kitirianglarp and Hewison2009, 465-6).

The early years in our three Latin American cases (Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia) share many similarities with the Turkish and Thai cases. Critical periods began with the electoral victories of “outsider” candidates who had called for fundamental institutional and economic reforms during their campaigns, and who then undertook executive aggrandizement once in office. Most notably, all three presidents pursued new constitutions early in their first terms.

Rewriting a constitution is not prima facie evidence of an intent to undermine democracy, but in these three cases the picture is complicated. On the one hand, all three presidents had explicitly campaigned on the idea, so they had earned a mandate for reform. Voters in Venezuela and Ecuador approved constituent assemblies via national referendums (Bolivia’s constitution specified a different mechanism). All three new constitutions were approved by separate national referenda (Stoyan Reference Stoyan2020). For these reasons, Corrales (Reference Corrales2018, 4) calls these reform efforts “moments of heightened … participatory democracy.” The three incumbents claimed, with some justification, that the new constitutions were more democratic than their predecessors, especially with regard to the expansion of political participation (see also Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016, 16, and Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017, 465). All three constitutions specified presidential term limits, and the new Venezuelan constitution added a recall provision that had no precedent in the prior constitution.

On the other hand, all three incumbents were attempting to concentrate power in the executive. Corrales (Reference Corrales2018) and Stoyan (Reference Stoyan2020) show that this effort was successful in Venezuela and Ecuador, and less so in Bolivia. In addition, to varying degrees, the three incumbents ran roughshod over legislatures and constitutional procedures to bring their projects to fruition. Substantial popular support does not change the fact that these were episodes of executive aggrandizement, and therefore they connote a degree of democratic erosion, even if they stopped well short of an authoritarian seizure of power.

Importantly, opposition actors responded with relative moderation in all three cases. Despite some talk, no serious efforts to derail the inauguration of the new presidents materialized. Opposition parties participated in elections for the constituent assemblies. The courts played a relatively independent role—while they ultimately backed the constitutional processes in all three countries, they also ruled against the government on other important matters. In Ecuador, the congress attempted to work with the Correa administration on this issue, asking only that the assembly would not gain the power to dissolve the congress (which, unfortunately for them, the assembly eventually did; Conaghan Reference Conaghan2008). Protest marches were mostly peaceful and focused on policy disagreements.

Bolivia stands out as a partial exception, as there were some incidents of violent opposition behavior during Morales’s first term. In 2007, protests related to the ongoing constituent assembly turned violent in Sucre and Cochabamba. Yet the protests aimed to influence the constitutional debates, and in fact were successful in limiting the consolidation of executive power in the new constitution; they were not aimed at Morales’s incumbency per se (Stoyan Reference Stoyan2020, 115). The following year, in the eastern media luna region, four administrative departments held autonomy referendums, which the government declared to be illegal, and violent clashes later that year left thirty dead. While the severity of the actual threat of separatism is open to debate, it is fair to say that we would not have predicted such aggressive opposition tactics so early in the critical period. Interestingly, in this instance Morales was able to defuse the crisis by appealing to democratic institutions: he promoted a recall referendum (for which the opposition governors would also have to face the voters), and he later helped to manage a process of power devolution to the regions, which significantly eased political tensions. Over the subsequent year or two, more moderate forms of opposition became the norm, until just recently.

Divergent Responses to Aggrandizement after the Second Election

We have shown common patterns of uncertainty and moderation in the initial stages of executive aggrandizement. Further, in all five of our cases, incumbents capped off their first term in office by winning a second terms with resounding electoral victories. These strong electoral mandates for aggrandizing incumbents only deepened the strategic dilemma for opposition groups, and this is the point at which we observe significant divergence in the trajectories of our cases. In some, opposition groups turned to irregular means of removing the incumbent after the second major election, while in others the opposition maintained a moderate posture for many years. The evidence suggests that democracy has a better chance of surviving when opposition actors stay moderate and play for time. Where they opt for more radical responses, democracy is likely to break down one way or another.

A. Turkey and Venezuela: Radical Opposition and Incumbent Takeover

Radical opposition behavior contributed to the breakdown of democracy in Turkey and Venezuela. Of course, Erdoğan and Chávez were the primary agents of breakdown in these two cases, and we do not intend to minimize their role. But it is important to consider that they succeeded where many other aggrandizing incumbents have failed. Even though opposition actors were responding to very real threats posed by the incumbent leaders, the evidence shows that radical responses failed to neutralize these threats. In fact, they motivated Erdoğan and Chávez to pursue further aggrandizement, and provided them with an opportunity to mobilize their social bases in support of their efforts.

As we have described, opposition groups in Turkey worked within the institutional framework for the first few years of Erdoğan’s premiership, and focused primarily on electoral mechanisms for removing the AKP from power. This focus began to change after the AKP’s victory in the 2007 general election, in which the party won 47 % of the national vote—more than twice as much as the main opposition party. Shortly after the new government was sworn in, the AKP began taking bolder actions on the issue of Islamic headscarves and promoted a constitutional change that would rescind the headscarf ban in Turkish universities. Turkey’s Chief Public Prosecutor responded to these actions by charging the party with promoting Islamic law and undermining secularism, in violation of the constitution, and demanded a ban on the party and its leaders—including Erdoğan and then-president Abdullah Gül. Leaders of the main opposition party supported the prosecutor and called on the AKP to respect the court’s decision. Although the closure case adhered to the existing institutional framework in a narrow sense, it was a move widely interpreted as a “judicial coup” by scholars, AKP supporters, and many international institutions, including the European Union (Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz2008; Gunter Reference Gunter2012; Müftüler-Bac Reference Müftüler-Baç2016). In the end, the Supreme Court ruled that the AKP had indeed violated the constitutional principle of secularism, but on a narrow vote, it decided only to remove the AKP’s public funding, rather than banning the party altogether.

The closure trial damaged Turkish democracy significantly. Most importantly, the trial led AKP leaders to take bolder steps to gain the control of the judicial branch. When rumors surfaced in 2010 that the Prosecutor might file a new closure suit against the AKP, the party immediately introduced a constitutional reform package that would solidify their control over the judiciary (Kalaycıoğlu Reference Kalaycıoğlu2012). Since the AKP parliamentary bloc did not have the votes needed to change the constitution, the reform was put to a public referendum. Even many liberal intellectuals and European Union officials, fearful of the anti-democratic moves of the judiciary, supported the reform effort (Bali Reference Bali2010). As a result, the AKP was able to assemble a large coalition, and the referendum was approved by a wide margin. In hindsight, many Turkish scholars view this referendum as a turning point in the AKP’s consolidation of power, especially since Erdoğan later used his influence over the judiciary to prosecute and repress opponents (Esen and Gumuscu Reference Esen and Gumuscu2016, 1585). This is a clear instance in which an irregular opposition effort to remove the incumbent caused additional damage to democratic institutions and eventually strengthened the incumbent’s position. Of course, the AKP might have attempted to subordinate the judiciary even if the closure case had not happened. But it seems unlikely that Erdoğan would have been able to build such a strong coalition in favor of the judicial reforms without the widespread perception that the prosecutor and the courts had overstepped their authority to begin with.

In the years after the 2010 referendum, Erdoğan continued to amass power and attack his opponents. Opposition groups, in response, experimented with various tactics, including increased personal attacks against Erdoğan (Selçuk, Hekimci, and Erpul Reference Selçuk, Hekimci and Erpul2019), large-scale street protests, corruption probes targeting high-ranking officials in the AKP, and formal and informal electoral alliances against the AKP (Selçuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020). Opposition political parties even had an opportunity to form a coalition government after the June 2015 general election. The chance was lost, however, when renewed conflict with the Kurdish separatist movement sparked a wave of nationalist sentiment, allowing Erdoğan to regain his parliamentary majority by calling snap elections in November of that year. While Erdoğan continued to undermine democratic institutions during this period, there were still significant limits to his power because of a notable decline in electoral support and the lack of enthusiasm among the AKP voters and leaders about Erdoğan’s plans to create a presidential form of government, which would provide an institutional foundation for his (heretofore) personalistic power (Aytaç, Çarkoğlu, and Yıldırım Reference Aytaç, Çarkoğlu and Yıldırım2017, 16-17; Yeşilada Reference Yeşilada2016, 25).

But then, in what Erdoğan immediately characterized as “a gift from God” (Gotev, Reference Gotev2016), a junta of Turkish military officers with ties to the Gulenist faction attempted a coup, on the night of July 15, 2016. Gulenists were the most politically powerful religious organization in Turkey during the 2000s. They controlled substantial economic resources, owned several media organizations, had strong ties to the military and judiciary, and commanded a certain degree of respect among the conservative public in Turkey. The Gulenist faction had supported the AKP during the first decade of AKP rule, but growing disagreements over ideology and bureaucratic power-sharing gradually led the Gulenists to join the opposition ranks during 2010s (Taş Reference Taş2018). Tensions increased when the AKP, emboldened by its victory in the November 2015 parliamentary elections, took steps to cleanse Gulenists from the military and judiciary. The coup attempt, occurring less than one year after the election, was the radical response of the Gulenist movement (Yavuz and Koç Reference Yavuz and Koç2016). As the coup was unfolding on the night of July 15, the plotters tried to recruit support from secular opposition groups. However, opposition parties and secular military officers fought against the coup on that night, together with the AKP leadership, their supporters, and police forces. As a result, the coup attempt had failed within a couple of hours.

In the aftermath, Erdoğan acted swiftly and decisively to solidify his hold on power. For several weeks, the AKP encouraged its supporters in all major cities and towns to spend nights outside, at city centers, “watching against another coup attempt,” and celebrating their victory against the putschists. Public approval for Erdoğan jumped to 68% during this period (Yavuz and Koç Reference Yavuz and Koç2016, 144). The secular opposition disavowed the coup and supported the AKP celebrations, partly in an attempt to limit Erdoğan’s ability to capitalize on the crisis. But their efforts failed. Erdoğan managed to seize the moment to institutionalize his authoritarian rule. The AKP first declared a state of emergency, and then began massive purges in the bureaucracy. Around 100,000 civil servants were expelled from the military, police forces, judiciary, and other bureaucratic cadres, all having been accused of sympathy with the “terrorist” Gulenist faction. Hundreds of journalists were arrested. Media outlets were banned. Opposition politicians, including the charismatic leader of the Kurdish party Selahattin Demirtaş and MPs from the Republican People’s Party (CHP), were jailed. Finally, taking advantage of his strong position, Erdoğan pushed forward a referendum to replace Turkey’s parliamentary system with a hyper-presidential regime. A referendum was held in April 2017, less than one year after the coup d’état and while the country was still ruled by a state of emergency. Turkish voters approved the reform, which finally institutionalized Erdoğan’s single-man rule, by a slim margin of 3%.

Our analysis reveals similar patterns in Venezuela. A more conciliatory approach in the first two years of the Chávez presidency gave way to highly visible, radical attempts not only to oppose Chávez’s policies, but to remove him from power, especially after he began his second term in January 2001 (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017, 464-468). Radical opposition behavior played into Chávez’ hands, allowing him to paint his opponents as coup plotters or enemies of democracy, and to justify his consolidation of power between 2002 and 2009 (see Cannon Reference Cannon2014; Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017; Rittinger and Cleary Reference Rittinger and Cleary2013). Due to space limitations, we discuss this process in detail in Part B of our online appendix.

B. Thailand: Radical Opposition and Incumbent Removal

Radical opposition behavior also contributed to the breakdown of democracy in Thailand. The 2005 parliamentary election was a major disappointment for the opposition. Thaksin’s Thai Rak Thai party (TRT) won 61% of the party-list votes, compared to 23% for the main opposition party. While Thaksin, who had previously said that he intended to stay in power for twenty years, was celebrating his electoral victory, his opponents were in fear of his sustained rule (Phongpaichit and Baker Reference Phongpaichit and Baker2009, 240). Some opposition figures tried to organize an anti-Thaksin movement around the issue of corruption immediately after 2005 elections, but these efforts did not generate significant momentum, at least initially (Phongpaichit and Baker Reference Phongpaichit and Baker2009, 257).

In early 2006, Thaksin made a crucial mistake that reenergized the opposition and brought about his downfall. He sold his family’s shares (worth US$ 2 billion) in a telecommunications firm to a company with ties to Singapore’s government, and did so in a way that avoided paying taxes on the transaction. Opposition groups accused Thaksin of corruption and even treason, based on the idea that the telecoms firm was a strategic national asset (Ferrara Reference Ferrara2015, 236). This touched off a new wave of protests, especially relying on the urban middle class, which was decidedly radical. Protestors called for Thaksin to quit while asking the King to appoint a new prime minister (Phongpaichit and Baker Reference Phongpaichit and Baker2009, 267; Kitirianglarp and Hewison Reference Kitirianglarp and Hewison2009), while leaders of the PAD movement appealed to the military to “step in” (Connors Reference Connors2008; Sinpeng Reference Sinpeng2013, 209). When Thaksin called for new elections in April 2006, opposition parties responded by calling for an electoral boycott. The goal was to create a constitutional crisis that could “create stronger grounds for the King to intervene” (Phongpaichit and Baker Reference Phongpaichit and Baker2009, 271). The plan worked, in a sense. Although Thaksin’s TRT won 56% of the party-list votes, millions of voters spoiled their ballots or abstained, causing valid turnout to fall below the required threshold in many districts. This left about forty parliamentary seats vacant, which prevented the parliament from being seated. The boycott and other disputes over the election created a political crisis, which deepened when the Election Commission declared the election null. In the meantime, opposition groups continued their street protests.

Eventually, in September 2006, the military intervened through a bloodless coup while Thaksin was abroad. Its initial goal was to establish a new democratic regime that also recognized the prerogatives of the military and bureaucracy, and nearly all opposition groups supported this project (Connors and Hewison Reference Connors and Hewison2008). However, new elections held in December 2007 returned Thaksinists to power. The following decade in Thai politics was a replay of the same political conflict between Thaksinists and radical opposition forces. Opposition movements organized violent street protests, opposition parties boycotted elections, and the Constitutional Court disqualified Thaksinist parties and politicians from elections. Ongoing polarization and instability eventually led to the establishment of a military regime in 2014.

C. Ecuador: Continued Moderation and Democratic Survival

Under Correa, Ecuador underwent a similar process of aggrandizement. We have already discussed the promulgation of a new constitution in 2008. The constituent assembly also assumed legislative powers for a short time, effectively sidelining the national congress until new legislative elections were held in 2009. That same year, the new national assembly passed electoral reforms (called the Código de la Democrácia) that restricted the ability of the press to report on opposition candidates, while creating a number of rules that favored press coverage for Correa’s own party (Sanchez-Sibony Reference Sanchez-Sibony2017, 131-132). In the ensuing years Correa turned his attention to the media, seizing some private outlets while expanding the role of state-owned outlets, and passing a series of reforms that restricted the ability of private media to report on the government (Sanchez-Sibony Reference Sanchez-Sibony2017, 131-132). These restrictions were aggressively enforced, leading to prominent cases of prosecutions against reporters and newspapers for publishing information critical of Correa or his policies. Changes to the judicial system, which included creating new courts packed with partisans, and firing judges who ruled against the government, provided legal cover for all of these incidents of aggrandizement. And finally, among many other instances, in 2014 Correa maneuvered to change the term-limit law that had been enshrined in the 2008 constitution. The Congress eventually passed an amendment removing term limits in December 2015. These attacks against countervailing institutions were not “tussles” (Waldner and Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018). They were significant power-grabs that damaged Ecuadorian democracy and created an uneven political playing field, akin to what Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2002) would call a competitive authoritarian regime (see also Levitsky and Loxton Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013; Sanchez-Sibony Reference Sanchez-Sibony2017).

Yet throughout Correa’s incumbency, opposition forces typically worked within the institutional framework to oppose Correa’s aggrandizement and to buy time.Footnote 4 Opposition parties did not overreact when Correa proposed the constituent assembly or when the assembly maneuvered to dissolve the legislature in 2007. Social movements and public protests focused on economic policy and the distribution of state resources. In response to Correa’s attacks on media freedom and civil liberties, private media and some popular organizations filed legal challenges in Ecuadorian courts and appealed, with some success, to international institutions like the Inter American Commission of Human Rights (Conaghan Reference Conaghan2017, 519; de la Torre and Ortiz Lemos Reference De la Torre and Lemos2016, 232). Throughout this period, opposition parties continued to participate in the electoral process, even knowing that they were disadvantaged by the electoral system and the restrictions on media coverage.

Opposition strategy began to bear fruit as the economic boom period came to an end in 2014, when they won several important local elections. They maintained their moderate strategies during the term limit debate, by collecting signatures, demanding a popular referendum, and organizing mass protests to dissuade the legislature from amending the constitution. Like many protests during Correa’s presidency, and in contrast to demonstrations such as the oil workers’ strike in Venezuela, these steps were aimed at policy, not at removing the president (Thompson Reference Thompson2015). In fact, opposition leaders took care to make sure that the protests did not turn against Correa himself, perhaps because they knew that this could backfire. For example, Jaime Nebot, the right-wing mayor of Guayaquil who led several large protests, said “The president has a mandate, nobody wants him to go with the recall” (El Universo 2015a), and that the protests were against the policies rather than the president (El Universo 2015b). At one protest, when some in the crowd chanted “Out, Correa, out!”, Nebot retorted that they would have to bring that about through the ballot box (El Universo 2015c; Agence France Presse 2015). Other protest leaders maintained similar positions.

Of course, it is fair to argue that some of the opposition’s moderation, especially on the right, resulted from the weakness of its political base, rather than a high-minded devotion to democratic principles. Especially in the early years of Correa’s government, opposition parties in Ecuador were “weak, divided and inefficient” (de la Torre and Ortiz Lemos Reference De la Torre and Lemos2016). Yet this is not a sufficient explanation of moderation in the Ecuadorian case, not only because weak opposition parties are common to all of our cases, but also because the Ecuadorian opposition remained moderate even as it began to win important electoral victories and mobilize mass protests during last few years of Correa’s presidency. Neither can moderation be explained by elite interests. Some scholars suggest that the economic relationship between the state and economic elites was more symbiotic in Ecuador than in some other Latin American countries (Bowen Reference Bowen, Luna and Kaltwasser2014), or that Correa did not actually threaten the core interests of the economic elite (de la Torre and Ortiz Lemos Reference De la Torre and Lemos2016, 237). But this would not explain continued moderation as Correa’s rule became increasingly threatening to economic elites and the military, especially during his third presidential term.Footnote 5 Opposition actors could have chosen a more radical path at several key moments, but they did not.

In the end, moderation paid off. The economic downturn, combined with the wave of opposition protests and Correa’s inability to frame them as radical coup plots, caused Correa to lose ground electorally. Eventually he decided that it would be a better strategy to not run in the 2017 election (Conaghan Reference Conaghan2017, 520). The moderate nature of opposition behavior might have also convinced Correa that he could safely return to power in the next election after 2017. The vote on the constitutional amendment went forward and term limits were repealed, even as Correa supported the candidacy of his former vice president, Lenín Moreno, with the expectation of maintaining a hand in the government. But after Moreno won the 2017 election, he broke from Correa and reversed some of the most troubling instances of aggrandizement under Correa’s presidency. For example, term limits were reestablished in 2018—against Correa’s wishes. Moreno also supported reforms, which the congress passed into law in December 2018, that reversed the most abusive elements of the national communications law. The moderation of the Ecuadorian opposition is not the only reason for this positive turn of events, but the opposition’s focus on democratic norms and procedures clearly contributed to the outcome of democratic survival in Ecuador.

D. Bolivia: The Limits of Moderation

As we write, Evo Morales is living in exile in Argentina, facing an active arrest warrant should he return to Bolivia. The interim government, whose legality is disputed, and which should have held elections within 120 days in any event, has cited the ongoing coronavirus quarantine as justification for repeatedly delaying elections, which are now scheduled to be held on October 18, 2020. The fate of democratic institutions in Bolivia is highly uncertain. Yet we can recognize patterns of aggrandizement and opposition response that conform to our theoretical framework.

We have already described opposition behavior that was more radical than we would have predicted during Evo Morales’s first term in office, from 2006–2009. This was also a period in which Morales pursued significant aggrandizement. His government arrested some opposition politicians in defiance of a court order in October 2008; he fought with the Supreme Court; he sent troops into Santa Cruz department in November 2009. He gained additional powers to appoint judges in February of 2010. Yet opposition forces maintained a focus on constraining Morales and strengthening countervailing institutions from about 2009 to 2018, and this stance helped to limit the damage to democracy during this time period (see figure 1). For this entire period, opposition groups continued to focus on election organizing, peaceful protests, and legal maneuvers to push for their preferred policies or outcomes. In some cases, their strategy succeeded in limiting Morales’s encroachments, such as when the electorate rejected a referendum to eliminate term limits in 2016.

Nevertheless, Bolivia’s institutions eventually reached their breaking point. The first signs of a turn towards a more confrontational dynamic came when Morales, reversing his earlier promises, signaled his intention to bypass the result of the 2016 referendum. His party (the Movimiento al Socialismo [MAS], or Movement for Socialism) announced in early 2017 that it was considering several “democratic” alternatives for abrogating term limits. In September 2017, the MAS filed a case with the Bolivian constitutional court (Tribunal Constitucional Plurinacional) seeking to overturn the referendum on the grounds that it violated Bolivia’s human rights commitments under international law (by preventing citizens like Morales from running for office). Two months later, the court ruled in Morales’s favor. After each of these incidents, opposition parties organized large street protests, which focused on the protection of democratic norms by calling for Morales and the courts to “respect the referendum.” Yet Morales ran for a fourth term.

Therefore the national elections in October 2019 occurred under conditions of greater distrust and uncertainty than the country had experienced in at least a decade. According to the official returns, Morales won 47% of the vote, down from his 61% share in the 2014 presidential election, despite a relatively strong economic outlook at the time. Discontent regarding Morales’ increasing authoritarianism was, arguably, an important reason behind this significant erosion of popular support (Derpic Reference Jorge2019). When the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (Tribunal Supremo Electoral) announced that Morales would win the election, with a margin just large enough to avoid a run-off, opposition groups cried foul. Street protests organized by the opposition quickly turned violent. At first, Morales defended the integrity of the electoral process. But when the Organization of American States (OAS) election observation mission claimed evidence of vote fraud, Morales proposed new elections to diffuse the crisis.Footnote 6 It was too late. On the same day, the military publicly suggested that Morales should resign, which he did (Díaz Cuellar Reference Vladimir2019).

As our theoretical framework would suggest, the irregular removal of the president generated additional damage to democratic institutions, from which they seem unlikely to recover in the short term. At the same time, the current crisis also results from Morales’s long history of aggrandizement, most notably the machinations by which he undermined presidential term limits to run for an unprecedented fourth term in office. As we have seen in our analysis of other cases, opposition groups clearly felt that Morales had already undermined democratic institutions, which would justify (in their minds) the more confrontational approach to which they turned after the October election. While a return to democratic institutions in late 2020 is not impossible, the combination of repeated aggrandizement and radical reactions makes this outcome unlikely. Moderate opposition behavior helped to sustain Bolivia’s democratic institutions for many years, but the institutional status quo became untenable once Morales’s aggrandizement had developed into a bid for perpetual power.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our goal has been to describe and explain the different regime trajectories that can occur in response to executive aggrandizement. Democratic breakdown is always a possibility. But we have shown that incumbents can also fail to consolidate authoritarian power, either because their behavior provokes their own ouster via nondemocratic means, or because democratic institutions are sufficiently resilient to remove them via the ballot box. We argue that opposition responses to aggrandizement help to determine which of these outcomes occurs. Moderation does not guarantee democratic survival, but radical responses tend to make things worse. Opposition actors are better able to protect democratic institutions when they appeal to electoral fairness and other democratic norms, while working to contain the incumbent rather than provoking her. But at the same time, moderation is difficult to sustain over time, as opposition actors face discrete moments of uncertainty and desperation that can induce them to opt for radical tactics.

In developing these arguments, we have relied on an agency-based approach that explains the trajectory of democratic erosion by undertaking a careful analysis of the uncertain strategic environment during critical periods. This agentic approach has often been criticized for ignoring the structural determinants of actors’ choices (Waldner and Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018). But as we have argued (in our online appendix), our case selection process managed to control for many structural factors, and remaining differences across cases do not suggest any clean covariation with the regime outcomes we want to explain. In addition, we endeavored in our case studies to focus on discrete instances of behavior and rhetoric on the part of specific opposition leaders that illustrated their agency during critical periods. In all the cases studied here, opposition actors had room to make different choices. This does not mean that their decisions were random, and further historical analysis might shed light on idiosyncratic decision-making processes of these opposition leaders. Our point is rather that structural conditions do not suggest a single behavioral path among the set of available alternatives, and in that sense they are not fully determinative.

One limitation of our study is that we cannot distinguish the causes of incumbent takeover and incumbent removal. In other words, when radical opposition behavior pushes the two sides into a winner-take-all conflict, what determines the victor? We can stipulate some clear, but theoretically thin, factors, such as having the support of the military. We also speculate that the social and geographic bases of support for the incumbent might influence the ultimate outcome. In Venezuela, Chávez initially did not have the support of the military, though after the attempted coup in 2002, he worked to ensure that he would never lack such support again (Rittinger and Cleary Reference Rittinger and Cleary2013). He also benefitted from having a high level of support in Caracas and other urban areas—when protests occurred, he was always able to draw on his social bases of support for counter-protests. In contrast, Thaksin’s support was disproportionately in the countryside; when the military moved to control Bangkok on the night of September 19, 2006, it faced little resistance. Finally, the level of unity among opposition actors may help to determine the consequences of radical attempts against the incumbent. One reason that the Gulenist coup failed was the lack of support among secular opposition groups. Conversely, there was broad opposition support for the 2006 coup in Thailand. Clearly there is more to be learned about how political agency interacts with structural and institutional factors to generate different regime outcomes in response to executive aggrandizement. But democratic institutions are more resilient than many scholars have portrayed them to be, and perhaps the opposition’s best course of action is to focus on protecting the democratic institutions that they have.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720003667.