The study of popular music presupposes a thing called ‘popular music’ – but how useful is this rubric, and to what does it refer? The quandary is not new. Indeed, in his editorial for the very first issue of Popular Music, Richard Middleton (Reference Middleton1981, p. 3) indicated that the nascent field must confront the question ‘what is popular music?’ Given such a daunting and potentially chimerical prospect, Middleton opted for an approach that, instead of answering this question directly, would tackle ‘a particular aspect of the topography of the area, which in turn has a bearing on the definitional question’ – the relationship between folk and popular musics (Middleton Reference Middleton1981). Throwing in another complex and contested term, he thus implied that such definitional predicaments do not have simple solutions, but rather involve a nexus of ideas reliant upon juxtapositions and acts of purposeful exclusion. Terms such as ‘popular’ and ‘folk’, in other words, convey a history of usage both scholarly and vernacular that we must deal with if we are ever to understand them fully. As Lawrence Levine (Reference Levine1988, p. 8) argues in his study of emerging aesthetic hierarchies in the USA during the 19th century, what we think of as popular culture has changed markedly over time: as ‘the products of ideologies which were always subject to modifications and transformations’, he attests, ‘the perimeters of our cultural divisions have been permeable and shifting rather than fixed and immutable’. The editors of Popular Music, however, pointed towards what they saw as the development of ‘a coherent, delimited field of study’ incorporating R&B, music hall, bossa nova, Tin Pan Alley, punk rock and highlife: although aiming for ‘a broad definition of popular music’, they employed this term to denote the mass-mediated products ‘of industrialised or industrialising societies’ (Middleton and Horn Reference Middleton and Horn1981, pp. 1–2).

As Philip Tagg notes, the tacitly ethnocentric ‘popular’ in both popular music studies and the International Association for the Study of Popular Music ‘originally sought to do no more than label what was, around 1980, still in the dustbin of conventional academe’ – those genres and practices barred from or overlooked by ‘canons then deemed fit for serious study in established institutions’ (International Advisory Editors Reference Editors2005, p. 135).Footnote 1 By the early 1990s, on the crest of the ‘new’ musicological wave in the USA, certain voices had begun calling for the discipline to become much more self-critical about such flagrant and essentialising omissions, demonstrated by Richard Leppert and Susan McClary's (Reference Leppert and McClary1989) Music and Society: The Politics of Composition, Performance and Reception and Katherine Bergeron and Philip Bohlman's Disciplining Music: Musicology and Its Canons. Canons, Bergeron (Reference Bergeron1992, p. 8) suggested, work as instruments of social discipline and surveillance, ordering bodies and discourse within fields of artistic and scholarly endeavour. Acts of imaginative resistance were hence required to approach marginal musics on their own terms – squinting, as she puts it, ‘into those unmarked spaces in order to discover what the discipline has not accounted for’. Such an undertaking involved a radical rethinking of the tools and apparatus that musicologists had traditionally brought to their objects of study: aesthetic autonomy, written notation, formalist analysis, the work concept, ‘great man’ history, and so on. Along with debates pertaining to gender, ethnicity, sexuality and globalisation, popular music appeared to ‘threaten musicology's most ingrained habits’ (Randel Reference Randel1992, p. 15).Footnote 2

Given that the insights of new musicology have permeated, at least to some extent, the discipline as a whole in the 21st century, it seemed apt for Popular Music to convene a virtual symposium in 2005 around the polemic ‘can we get rid of the “popular” in popular music?’ Two distinct attitudes emerged. First, in Alf Björnberg's words, that as so much music today shares its modes of production and circulation we have ‘much to gain and little to lose from a dismantling of the distinction between “popular music” and “music”’ (International Advisory Editors Reference Editors2005, p. 134) – a position calling attention to studio recording practices, business protocol and modes of digital dissemination uniting classical music, world music, jazz and indie with the mainstream. The second was that the term should be preserved because of its descriptive utility and capacity to stimulate pedagogical discussion – in Tagg's words, its very ‘conceptual messiness’ being ‘one of its must useful characteristics’ (International Advisory Editors Reference Editors2005, p. 136). Among those wishing to retain the term, Middleton drew attention to a further rift between two conflicting perspectives that he labelled ‘descriptivist’ and ‘discursivist’ (p. 143). Exemplifying the ‘descriptivist’ view, Simon Frith defended the existence of ‘a specific object of study … that must be approached differently from other kinds of music’ (p. 134). The ‘discursivist’ stance, by way of contrast, maintains that popular music does not exist per se, but rather functions, as Peter Wicke contends, as ‘a pure discursive operator, without any fixed meaning or content’ (p. 143).

Clearly, such disputes reveal that we are no closer to achieving an answer to the question ‘what is popular music?’ than scholars were in the 1980s. In pursuing an answer, however, we risk forgetting that the question itself is suspect, implying an invariant essence that Foucauldian genealogy would be swift to challenge. The history of a concept such as the popular should aim to disturb – revealing ‘the heterogeneity of what was imagined consistent with itself’ (Foucault Reference Foucault and Rabinow1984, p. 82). Helmi Järviluoma offers the most enlightening response to the symposium in this respect:

To me it is not particularly interesting to try to find one more top-down – and as Morag Shiach has noted, often men's – definition of the ‘popular’ according to its contents. Rather, it is interesting to hear how, when and where it is used and needed; how its contents are being produced historically and situationally in the shifting tide waters of ‘high’ and ‘low’. Out goes the dream of sameness. As some feminist theorists might put it, it is useful for us both to use the term (‘do it’) and ‘trouble it’ simultaneously. (International Advisory Editors Reference Editors2005, p. 140)Footnote 3

This article takes seriously Järviluoma's call to ‘trouble’ the popular, setting aside gestures of definitional foreclosure in favour of tracing the ways in which the term ‘popular music’ was understood at a crucial point in time in a particular geographical locale. In so doing, I show that the popular, rather than representing one facet of what Andreas Huyssen (Reference Huyssen1988, p. viii) has termed the ‘Great Divide’ between high art and mass culture, cuts across this discourse. Concentrating on a period in Britain from the ascendency of the music hall in the 1860s to the emergence of electric recording in the 1920s – the era, in other words, during which modernity becomes increasingly characterised by an antagonistic relationship between elites and consumer entertainment – I show that the popular held a number of rival meanings, being used in reference to the work of ‘high’ art composers as well as to dismiss ‘low’ commercial music. Popular music, in short, is one of those inescapably protean concepts that, as Frederic Jameson insists (Reference Jameson1981, p. 9), must always be historicised. Before pursuing this argument, it is worth pausing to revisit a few of the most significant theoretical attempts to circumscribe the popular.

The deadlocks of definition

Scholarly endeavors to define the popular have invariably run aground.Footnote 4 In his much-cited essay ‘Notes on deconstructing “the popular”’, Stuart Hall rejects both commercial and folkloric definitions, urging scholars towards a view of the popular as a shifting terrain of containment, resistance, identification, domination and reform. As Hall points out, ‘market’ definitions incline towards either a condescending model of passive consumers in a manipulative culture industry or the heroic and equally unsustainable alternative of a popular milieu entirely free from power relations. ‘Descriptive’ definitions likewise fall short given that they reify the popular, denying change in aesthetic categories. What Hall underscores is that such errors arise as a result of our propensity ‘to think of cultural forms as whole and coherent’, whereas they are in fact ‘deeply contradictory’ (Reference Jameson1981, p. 233). Hall's deconstructive act was thus to find secreted within the term popular an unstable array of identities. To overcome this obstacle, Hall turned to a dynamic hypothesis involving a cultural battleground in which hegemonic power intersects with and shapes subjugated communities. ‘What is essential to the definition of popular culture’, he concludes, are the relations that ‘define “popular culture” in a continuing tension … to the dominant culture’ (p. 235). This Gramscian model nevertheless had its own problems. Despite admitting that ‘just as there is no fixed content to the category of “popular culture”, so there is no fixed subject to attach to it’ (p. 329), Hall appeared unwilling to abandon a conception of the popular as an oppressed domain allied with the disruptive signifying practices of punk. The popular, Hall implied, is always actively struggling against a power bloc – but, we might protest, what if popular culture was a constituent of this very power bloc? Focusing on the ways in which dominance and subordination are formulated, Hall's definition finally collapses into the analysis of a process.

Responding to the shortcomings of this dialectical approach characteristic of the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies,Footnote 5 Holt Parker proposes a sequence of definitions derived from Bourdieu's notion of cultural capital and Arthur Danto's (Reference Danto1964) theory of the ‘artworld’. Directing attention towards institutions that hold the power to authorise what is art and therefore to establish the boundaries between cultural fields, Parker advances a thesis that ‘popular culture is unauthorized culture’ – a realm consisting of ‘products that require little cultural capital either to produce or else to consume’ (Parker Reference Parker2011, pp. 165, 161). The idea that popular culture exists outside the bounds of official recognition and ‘ceases to be popular when it is authorized’, however, recapitulates the romantic vision that Hall was at pains to dismantle (p. 166). In musical terms, Parker's theory leaves us with an extremely narrow collection of vernacular practices restricted to examples such as early hip hop in the Bronx, skiffle bands, work songs and children's music. As Parker maintains, each field of cultural production nonetheless ‘has its equivalent of the artworld, and each level of cultural activity, too’ (p. 167). Each field also has its own forms of ‘subcultural capital’ (Thornton Reference Thornton1995), undermining the idea that such areas are entirely devoid of authorisation. Ironically, Parker's definition thus returns us to Hall's relational model with the focus shifted onto processes of acquiring, evading, or being excluded from institutional endorsement. In consequence, he is forced to admit, a precise definition of the popular is ‘elusive, perhaps delusive’ (p. 169).

Whereas cultural studies sees the popular enacting ‘resistance through rituals’ (Hall and Jefferson Reference Hall and Jefferson2006), Frankfurt School critical theory posits a pessimistic counterpoint: mass culture as ritualised submission, conformity and delirium. Writing in 1941, Theodor Adorno argued that popular music could be identified by two interrelated characteristics: standardisation and pseudo-individualisation. In his view, such material consists of a series of interchangeable elements that bear no relation to a larger whole – their functional, pre-digested content merely encouraging recognition. As a result, Adorno (Reference Adorno and Leppert2002, p. 438) claims, ‘the hit will lead back to the same familiar experience, and nothing fundamentally novel will be introduced’. Popular music appeared to dictate how listeners behave, removing the need for effort, activity and independent thought. How did this come about? The answer: an unbreachable system of competitive imitation driven by the imperatives of an industrial marketplace. As paradigms of instrumentality, commodity fetishism and glamorised ‘plugging’, song hits engendered ‘a system of response-mechanisms wholly antagonistic to the ideal of individuality in a free, liberal society’ (p. 442). Such standardisation, however, had to be concealed or forgotten in order not to provoke hostility. This process of ‘endowing cultural mass production with the halo of free choice or open market’ meant that artists or genres within the popular domain provided ‘trademarks of identification for differentiating between the actually undifferentiated’ (pp. 445–6).Footnote 6 Representing a kind of mass infantilisation or automatism, Adorno concluded, popular music was a cathartic leisure product requiring no effort to consume that served principally to distract the population from reality while fortifying the asymmetries of capital. Marking an ‘adjustment to injustice’ (p. 464) and the cessation of resistance to authoritarian regimes, popular music was thus a prophet of social catastrophe – a harbinger and aesthetic analogue of fascism in the free world.

Grappling with Adorno's argument became a rite of passage for early scholars of popular music (Frith Reference Frith1978; Paddison Reference Paddison1982; Gendron Reference Gendron and Modleski1986; Middleton Reference Middleton1990). What I wish to highlight is the extent to which Adorno elides concrete detail in favour of an analysis grounded in the categorical distinction between two homogenous ‘spheres’ of music – the popular (indicated by big band hits of the Paul Whiteman era) and the serious (indicating Western classical music as well as ‘bad’ serious music). Predicated on an endorsement of modernist avant-gardism as an aesthetic corrective through the ideal of negation, Adorno's (Reference Adorno and Leppert2002, p. 460) theory presumes belief in the historical ‘autonomy of music’ to differentiate material earmarked by ‘a mere socio-psychological function’: both are inaccurate assumptions that downplay the longstanding transactions between ‘serious’ and ‘popular’ domains, as well as the systems of thought inaugurating a view that some music floats free of social contingencies. Indeed, Adorno falls into the trap Hall outlines by establishing a timeless vision of the popular drawn primarily from a manual entitled How to Write and Sell a Song Hit (Silver and Bruce Reference Silver and Bruce1939) that he wields as a critique of capitalist imperialism. As he later emphasised with his colleague Max Horkheimer in their seminal Dialectic of Enlightenment (Reference Adorno, Horkheimer and Cumming1997), Adorno understood mass culture as evidence of Enlightenment's janiform progress towards rationalised ‘mass deception’ – dismissing what Jameson (Reference Jameson1979, p. 144) later characterised as the ‘Utopian or transcendent potential’ of commodity culture. We cannot fully do justice to such products, Jameson affirms, without taking seriously their trace, however faint, of a positive function independent of the commercial order from which they emerged. More significantly, as Frith (Reference Frith1996, p. 15) notes, a simplistic equation of the popular with the market reveals little about why such goods are chosen, valued or rejected by their consumers.

So where does this leave us? Defining the popular in the abstract seems to lead to an unhelpful and confusing impasse. However unfathomable this stalemate appears, the popular harbours one element that stubbornly persists: derived from the Latin adjective populāris, the word invokes a conceptualisation of ‘the people’ and is thus unavoidably political. In spite of the term's mutability, as Middleton (Reference Middleton2006, p. 34) argues, ‘the people as subject is embedded somewhere within it, and with an emotional charge that will apparently just not go away’ – especially as it affords a certain experience of jouissance. If we do away with the Lacanian scaffolding that he adopts by way of Slavoj Žižek, Middleton's argument is instructive in that it begins to register a more historical understanding of the popular. The voice of the people, he reminds us, ‘is always plural, hybrid, compromised’, existing in dialogue because it ‘owes its very existence, and historical potential, as “popular” to a machinery (economic, cultural) put in place by those superiors whom it would then want to usurp’ (p. 23). Extending Paul Gilroy's (Reference Gilroy1993) ideas, the voice of the people thus forms a ‘counterculture of modernity’ and, furthermore, ‘is constitutive of modernity … its role not only reactive but also productive’ (Middleton Reference Middleton2006). In other words, the popular has a particular resonance in modernity as both determinant and symptom of social change. What this theoretical formulation sidesteps, however, is a genealogy of usage: how, precisely, was the term employed during this period of upheaval?

In what follows I map out the beginnings of such a genealogy, focusing on the ways in which the term ‘popular music’ was engaged discursively by metropolitan commentators in Britain during an era of rapid urbanisation that witnessed not only striking advances in technology and mass communications, the emergence of a professional music industry and the early revolutions of artistic modernism, but also unsettling developments across the political spectrum.Footnote 7 This fin-de-siècle world warrants our attention, in short, as the crucible of Western modernity (Saler Reference Saler2015, p. 47). As Peter Bailey (Reference Bailey1978, p. 5) proposes in his classic study of leisure during the Victorian era, the second half of the 19th century brought about new forms of recreation that ‘threatened to outstrip the reach of existing systems of social control’. The response among concerned members of the intelligentsia was an eagerness to restructure leisure activities along ‘rational’ lines, supplanting ‘noxious’ pursuits with activities that might heal enduring social divisions triggered by industrialisation. My argument is that use of the term ‘popular’ fell into two broad categories during this period: first, as a way to identify and/or denigrate mass culture; and second, in a more ambiguous way to establish a pathway for social reform and to champion approved aspects of working- or middle-class life. Whereas the first dismissed the masses owing to their habits of consumption, the second aimed to rescue this populace from the culture industry. These discourses, however, represent two sides of the same coin – highlighting the injurious aspects of entertainment while offering a substitute predicated on temperance, edification and respectability.

A desert of semi-lunatic trash

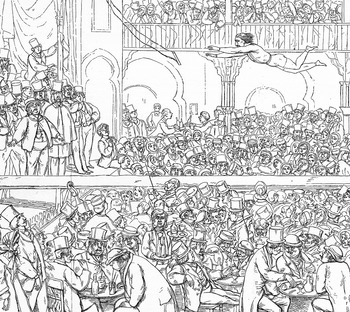

‘Concert halls and such like places of public entertainment’, an 1861 article in the Cornhill Magazine observed, ‘have lately become so like taverns, or taverns have become so like concert halls’ that it was hard to tell them apart (Anon. 1861, p. 713). Accompanied by a Hogarthian sketch featuring the French acrobat Jules Léotard performing a flying trapeze at the Alhambra Theatre in London's Leicester Square (Figure 1), the magazine's vision of the popular was a West End music hall in which an intoxicated and multitudinous lower middle-class audience absorbed a plethora of diversions that stimulated the senses but required little effort to apprehend:

It must be very much better than a play – if we may form an opinion from the numbers who crowd to these places – to be able to sit with a little table before one, with, for instance, a bottle of beer upon it, to have one eye turned upon an acrobat, the other gazing affectionately at the drink, a cigar hanging lazily from the mouth, from which curls of smoke come forth leisurely and languidly, for one's ears to imbibe the while the brilliant but violent vocalisation of modern Italy, or the refined comic song of our own land, happy with either, and considering each song, dance, or other performance with an impartial look of contentment (Anon. 1861)

Figure 1. ‘Bird's-Eye Views of Society. No. IX: A Popular Entertainment’ (detail), Cornhill Magazine 4/24 (1861), foldout image adjacent to p. 713.

Such depictions both reflected and helped to shape the perception of a burgeoning leisure industry in the capital. As an indication of commercialism and mass demand, the popular was a force to be reckoned with: an 1862 article in the Saturday Review affirmed that ‘the especial fickleness of the general public in matters of amusement renders the path of any caterer for their entertainment who may be bold enough to deviate from the conventional and well-beaten track, anything but a path of roses’ (Anon. 1862, p. 710). Most attempts to offer such alternatives, it noted, were marred by ‘what is, unfortunately, but too correctly called the popular element’ (p. 711).

The logician and political economist W. Stanley Jevons bemoaned this situation some 17 years later, remarking on what he saw as ‘a tendency in England at least, to the progressive degradation of popular amusements’: when ‘our English masses try to amuse themselves’, he went on, ‘they do it in such a clumsy and vulgar way as to disgust one with the very name of amusement’ (Jevons Reference Jevons1878, p. 500). For Jevons, the music hall was a prime indicator of such public errancy:

What can be worse than the common run of London music-halls, where we have a nightly exhibition of all that is degraded in taste? Would that these halls were really music-halls! but the sacred name of music is defiled in its application to them. It passes the art of language to describe the mixture of inane songs, of senseless burlesques, and of sensational acrobatic tricks, which make the staple of a music-hall entertainment. Under the present state of things, the most vulgar and vicious lead the taste, and the conductors of such establishments passively follow. (Jevons Reference Jevons1878, p. 500)

Jevons stated, however, that the cause lay not with the lower classes but with an elite who refused to cultivate civilising forms of leisure. In his view there appeared to be little provision for wholesome recreation in the metropolis, leaving doors open for shrewd caterers to vice and coarseness – ‘no necessary characteristics of hard hands and short purses’, but symptoms of ‘the way in which for so long popular education and popular recreation have been discountenanced’ (p. 513).

Variants of this opinion resounded into the 20th century as the music hall morphed into a more reputable, rationalised and highly lucrative enterprise spanning the country.Footnote 8 Writing during the First World War, for example, the theatre critic William Archer (Reference Archer1916, p. 253) remarked that such institutions were ‘certainly not the least among the forces that shape and colour the mind of a nation’. He continued:

Every night and almost every afternoon tens of thousands of men and women, boys and girls, flock to the ‘Empires’ and ‘Palaces’ which have arisen in every centre of population above the grade of a village. That they are deeply influenced, morally and aesthetically, by the entertainments presented to them, is scarcely to be disputed. (Archer Reference Archer1916, p. 253)

Much like contemporaneous folk revivalists, Archer dismissed the music hall as a ‘desert of semi-lunatic trash’ that had ‘killed a genuine vein of lyric faculty in the English people’ (p. 258). To support this argument, Archer drew a tripartite distinction between ‘culture-poetry’, ‘folk-poetry’ and the ‘high-pressure activity’ of the music hall (p. 257) – a reinscription of the art/folk/popular classification that, as Matthew Gelbart shows (Reference Gelbart2007), emerged from European Romanticism and gave the folksong revival its historiographical underpinning.Footnote 9 Juxtaposing music hall material with folksongs, however, revealed a semantic ambiguity: ‘these delightful songs’, Archer (Reference Archer1916, p. 258) declared, ‘are spontaneous products of popular, as opposed to professedly literary, talent’. What Archer was suggesting, in line with presumptions championed by Cecil J. Sharp in Reference Sharp1907, was that truly ‘popular’ material was categorically distinct from composed popular song – exemplifying what Derek Scott (Reference Scott2008, p. 109) describes as an ‘ideological schism’ drawn between mass-produced music and songs imagined to be uncontaminated by commerce.Footnote 10

Archer had little faith in the mass population's temper, concluding that there existed a ‘lack of any imperative public demand for intelligence and refinement’ in entertainment (Archer Reference Archer1916, pp. 260–61). Imagining military officers spending one final night with their betrothed witnessing ‘a piece of garish and cynical inanity, humiliating alike to our national and to our personal self-respect’ made it seem ‘very doubtful whether England is worth fighting for’ (p. 261). As the emblem of a rapidly modernising world, Archer ultimately saw popular music as a threat to social order:

In the strenuous years that lie before us, when our whole existence may depend upon our making the very most of such moral and intellectual qualities as nature has bestowed upon us, the enormous wastage involved in our lower forms of popular entertainment must, if unchecked, lead to disastrous consequences. How is it to be checked? Only by awakening in the public a reasonable sense of responsibility. (Archer Reference Archer1916)

The people might be rescued, Archer counselled, by refusing to follow the crowd and instead taking guidance from a directory that would separate those entertainments that were decent and desirable from those that were ‘indubitably noxious’ (Archer Reference Archer1916). What was at stake in such outwardly trivial matters? Nothing less than civilisation itself: ‘the relaxation of moral and intellectual fibre involved in the encouragement of such entertainments’, he affirmed, ‘is a serious national evil’ (p. 262).

There is a curious slippage in such arguments between the disparagement of ‘popular’ material and a condemnation of ‘popular’ sensibility (of which popular material seems to be either a disturbing symptom or cause). Although such material was often dismissed as an undifferentiated and pestilent mass, the population's taste in music was by all accounts supremely fickle and impossible to pin down. As one contemporaneous critic noted, the commercial publication of sheet music was accordingly a ‘highly speculative and uncertain’ business (Tompkins Reference Tompkins1902, p. 746). Appearing in both the New York Evening Post and the Musical Standard, an article entitled ‘The Making of a Popular Song’ likewise reported that composers working in the music publishing district centred around West 28th Street in Manhattan were not in fact able to predict which songs would eventually become hits:

In spite of all their needed business assurance, you cannot find a single inhabitant of Harmony Square who will venture to give you a recipe for the making of a popular song. Even the man who has accomplished one cannot tell you how he did it. A big success does not ensure another. A man may write one; he may write more than one, with failures tucked in between; or he may never write another. ‘It all depends,’ says the publisher. ‘And all the pushing in the world won't make the public swallow a song it doesn't want’. (Anon. 1906, p. 247)Footnote 11

The term popular, it seems, was not used to describe all commercially oriented sheet music, but was reserved for exceptional pieces that happened to resonate with the zeitgeist or contained a kernel of truth that many people could relate to – a classic example being Charles K. Harris’ 1892 favourite ‘After the Ball’.

This article's dispassionate take on New York City's commercial music hub was relatively uncommon. From around 1903, as Keir Keightley (Reference Keightley2012, p. 718) argues, appellations such as Harmony Square were supplanted in the press by the pejorative and enduring moniker Tin Pan Alley – ‘a phrase that amplified the disdain discernable in the sound of the tin pan’. The conjoining of tin metal, cheap cookware and the alleyway, he proposes, conjured up a powerful node of meanings inseparable from a melancholic disillusionment with industrialised modernity. During the late 19th century mass-produced tin cans became signifiers of junk, shoddiness, lowness and inauthenticity, standing synecdochically for the degradations of the modern world at large. When applied to commercial music publishing, Keightley argues, such metonymy encouraged the view that the industrial production of culture equated with ‘the industrial production of trash’ (p. 721). Tin Pan Alley, in other words, came to symbolise not only cheap, poor quality music, but also the poor taste of consumers – likened to the inferior inhabitants of urban slums, strewn with the mass-produced detritus of the modern city. Parallels with Frankfurt School critique are not hard to discern. Indeed, Adorno (Reference Adorno and Ashton1976, p. 26) makes explicit recourse to the tin metaphor, proposing that popular music uses forms ‘as empty cans into which the material is pressed’, avoiding dialectical interaction between form and content. His claim was not entirely unjustified: the anonymous article in the Musical Standard notes that such material was knowingly formulaic, falling into a number of overlapping yet characteristic subgenres (see Goldmark Reference Goldmark2015). All of this material, the writer stressed, appealed to an earnest or ‘primary emotion’ (Anon. 1906, p. 248).

This notion of ‘primary’ or ‘primitive’ emotional appeal provided the focus of contempt for the most infamous genre of mass consumed music associated with Tin Pan Alley, inflaming passions in both Britain and the US: ragtime. ‘Never in the complete musical history of our country’, an article in the Washington Post stated, ‘has one style of music caused so much dissension’ (Anon. 1900). In Britain, ragtime was inseparable from the transatlantic histories of blackface minstrelsy – a ubiquitous theatrical entertainment that, unlike its raucous counterpart in the USA, established a broad and respectable appeal during the 19th century (Lott Reference Lott1993; Pickering Reference Pickering2008). The Reverend H.R. Haweis (Reference Haweis1871, pp. 517–18) considered the form to be a ‘branch of strictly popular music’, albeit one based on a ‘parody’ of ‘genuine negro melody … as much like the original article as a penny woodcut is like a line engraving’. Coinciding with the height of Imperialism, burnt cork performance had given birth to a ‘coon’ song craze around the fin de siècle, simulating American blackness as a carnivalesque subversion of Victorian decorum that worked to uphold racialised visions of difference.Footnote 12 As Michael Pickering (Reference Pickering2000, p. 176) argues, minstrelsy activated something akin to a hall of mirrors in which psychological conflicts ‘were grotesquely magnified or dissolved and images of self were inverted, reversed, thrown bizarrely out of shape, and then reassuringly restored’. With its roots deep in this tradition, ragtime offered a transgressive rendering of imagined otherness that – as printed sheet music – offered the thrill of donning a musical blackface mask in the home. The genre, moreover, signalled a new experience of modernity sparked by the rise of a globalised entertainment industry, gramophone and wireless technology, youth culture and liberating forms of social dance in which prior constraints on women and sexuality were openly challenged (Baxendale Reference Baxendale1995; Berlin Reference Berlin1980).

Evaluations of ragtime with an unequivocally racialised bearing emerged in Britain, setting a precedent for the reception of early jazz (Parsonage Reference Parsonage2003). One writer for the Academy, for example, praised the leader of the Manchester brass band ‘The Besses o’ th’ Barn’ for refusing requests for the genre in 1913:

Much as I enjoyed their rendering of the operas of my childhood – Donizetti, Rossini, Verdi – their fine attack, their wonderful part-playing of hymns, I appreciated most of all this sturdy resistance of a perverted taste for hashed-up nigger melodies that has lately filtered down from the smart set to the social underworld, till we hear it alike on the Steinway grand in my lady's drawing-room and on the barrel organ in the slums. There is no profound mystery about this curiously uneven measure, for I have heard it, or something very like it, coming from the doors of negro shacks in Louisiana and even thrummed on tom-toms by savages in Africa, and if Europe is to go to such ideals for its music, then truly we are looking backward. (F. G. A. 1913)

Unlike the safe charade of blackface, rhythmic dexterity appeared to contaminate the unalloyed purity of Western culture – demonstrating the lie at the heart of colonialism's Manichean vision. For the author, such music brought with it not only ‘bad taste and foolishness’ on both sides of the Atlantic, but also the dread of cultural miscegenation (F. G. A. 1913). Ragtime, in short, represented an unpleasant incursion of musical and somatic alterity. Such views were not untypical of writing on black popular music at the time, much of which equated jazz with ‘jungle’ barbarism. ‘With its savage gift for progressive retardation and acceleration, guided by the sense of swing’ one article averred, jazz ‘reawakened in the most sophisticated audience instincts that are deep-seated in most of us’ (Anon. 1918). Ultimately, African American music signalled a disquieting libidinal atavism that risked undermining the dignity and hard-won sophistication of modern civilisation – a fear that revolved around the body's untamed responses to complex rhythmic motion.

The idea that syncopated black music presented a menace to polite society had numerous adherents. In an article for the English Review entitled ‘Ragtime: the new Tarantism’, music critic Francis Toye (Reference Toye1913, p. 654) decried the genre's association with ‘dances of a lascivious or merely ridiculous kind’ accompanied by ‘yells or interjections of most revolting sound’. Such music, he argued, was an instigator of social and mental instability through its volatile and illogical rhythmic impetus:

There are true rhythms and true movements that are in accordance with nature, which is sanity, and false rhythms and false movements, which are allied with hysteria, neurosis and nervous instability generally … Nobody denies the rhythmical power of rag-time, and rhythm is always ‘stimulating’. But in this case the stimulus is that of an irritant. These ‘crotchety’ accents, these deliberate interferences with the natural logic of rhythm this lengthening of something here and shortening of something else there, must all have some influence on the brain. The behaviour of the chorus during the rag-time songs of the Alhambra revue, for instance, is not without significance. Any unsophisticated visitor from Mars, who did not know of their excuse, would judge from their looks, their movements, and their strident but pathetic yells that they were raving lunatics only fit for the Martian equivalent of a strait-jacket. (Toye Reference Toye1913, pp. 656–7)

Such views, as John Baxendale (Reference Baxendale1995, p. 147) notes, linked ‘degeneracy, moral chaos and sexual license with the corrupting power of both women and the racial “other”’. Popular music and socio-political order were thus fundamentally intertwined. Indeed, the one motif connecting discourse on popular music during this period is a repeated reference to the aphorism by Scottish writer Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun (Reference Fletcher1732, p. 372) that ‘if a man were permitted to make all the ballads, he need not care who should make the laws of a nation’. The anxiety underlying this view was that popular music not only seemed to exercise an apparently untameable influence over its citizens, but also – as an echo of the conduct and tastes of the populace – indicated the collective mental, spiritual and physical health of a body politic.

Intellectuals writing at the turn of the 20th century were particularly attuned to this vision of the popular as a dangerous and disorderly realm defined by the intersection of free market capitalism and mass demand for frivolous amusement. Expounding a utopian theory of individualism in his 1891 essay ‘The soul of man under socialism’, for instance, Oscar Wilde berated popular taste as it stymied freedom of expression as well as hindering artistic progress and innovation:

The public has always, and in every age, been badly brought up. They are continually asking Art to be popular, to please their want of taste, to flatter their absurd vanity, to tell them what they have been told before, to show them what they ought to be tired of seeing, to amuse them when they feel heavy after eating too much, and to distract their thoughts when they are wearied of their own stupidity. (Wilde Reference Wilde2001, p. 142)

For Wilde, popular authority was thus ‘a thing blind, deaf, hideous, grotesque, tragic, amusing, serious and obscene’ (p. 154). As John Carey argues, this conviction was typical of a highbrow elite hostile to the emergence of a new reading public during the 19th century: the denial of humanity to the notional masses or even a eugenic thirst for their extermination afforded ‘an imaginative refuge’ for writers including D.H. Lawrence, W.B. Yeats, and Virginia Woolf (Reference Carey1992, p. 15). Art not only had to be autonomous from society and from use value, but also located beyond the inclinations and aptitudes of the populace – distinguishing features of modernism indebted to a confluence of Nietzschean rhetoric and Kantian aesthetics. As with folk revivalism, modernism was consequently one of the products of mass culture.

A recreation and a solace

Confusion over the term ‘popular’, however, was widespread. An editorial from the Musical Standard in 1871, for instance, declared that although the term ‘popular music’ was ‘in very common use … it would be difficult to define what description of music most deserves such a distinction’ (Anon. 1871, p. 37). This article continued:

One class of music is popular with a certain standard of taste, and another class is considered popular by those with whose taste or degree of musical education it is most in accordance. Some consider cheap, that is, low-priced music, ‘popular’. Some write music under the idea that it will meet certain popular demands, either in consequence of its simplicity or its passages of a sensational nature. Publishers can also apply the term to what class of music they think proper; but in the majority of cases the term ‘popular’ may be regarded as assumed by interested authors and publishers, rather than deserved as the result of public opinion. (Anon. 1871)

Such ambiguity continued to plague the term as the new century advanced into the jazz age: a 1921 article in the Manchester Guardian entitled ‘What is Popular Music?’ drew attention to the many unanswered questions still surrounding the term: ‘What is “essentially popular” music?’ it queried ‘Is it good music or bad? Is it native or alien? Is it new or old? Is it of necessity even “light” music?’ (Anon. 1921). The 1871 editorial in the Musical Standard was emphatic on this point:

The one instance where the term ‘popular music’ is strictly applicable, is in the case of the cheap editions of works by writers of undoubted reputation. The cheap editions of Beethoven's pianoforte music richly merit the designation of ‘popular’; and so do many of the cheap forms in which Handel's and Haydn's oratorios are given to the public. (Anon. 1871, p. 37)

Motivating this statement was the notion that such music – as categorically ‘good music’ – needed to be put ‘within the reach of the masses’ for their edification. Through the study of music ‘in its higher branches’, the writer hoped, ‘good music would soon become the popular music of the multitude’.

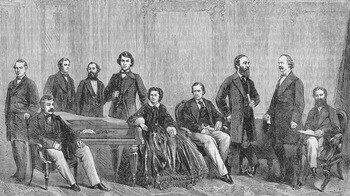

The idea of popular music was inescapably entangled with the principles of social reformism.Footnote 13 As Jevons proclaimed, ‘the idea that the mass of the people might have their refined, and yet popular amusements, is only just dawning’ (Reference Jevons1878, p. 501). Wishing to ‘secure the ultimate victory of morality and culture’ (p. 499), Jevons saw music as one of the cornerstones of recreational change: ‘the question is, the Free Library and the News Room versus the Public-house, and … the well-conducted Concert versus the inane and vulgar Music-hall’ (Jevons Reference Jevons1878, p. 502). Characteristic of this middle-class mission to introduce concert music to the masses was a series of reduced-cost performances initiated by the publishing company Chappell & Co. featuring the acclaimed Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim at the newly opened St James's Hall, Piccadilly. Christened the Monday and Saturday Popular Concerts (Figure 2), these events gained a firm foothold in London: according to one contemporaneous critic, ‘the favour with which the public received the Mozart, Beethoven, and Mendelssohn nights … showed that an audience might always be relied upon where the orchestral works of any of the great masters in music formed the staple entertainment’ (Anon. 1862, p. 710). Jevons himself praised the series, although wished to see more stirring and publicly visible events of popular music taking place across the captial. ‘Those who have noticed the manner in which a confessedly popular and casual audience receive the Symphonies of Beethoven’, he added, ‘will not despair of musical taste in England’ (p. 510).

Figure 2. ‘The Monday Evening Popular Concerts: The Instrumentalists’, Illustrated London News, 25 April 1863, p. 465. Figures depicted: Julius Benedict, Samuel Arthur Chappell, Arabella Goddard, Charles Hallé, Joseph Joachim, Carlo Alfredo Piatti, Louis Ries, Prosper Sainton, Lindsay Sloper, Henry Webb.

During the late 19th century, as Dave Russell has documented (Reference Russell1997), a taste for art music was not restricted to wealthy elites. Although meanings differed depending on context, musical eclecticism in both amateur and professional realms was a feature of a society in which repertoire and genres were, to some extent, shared between classes. Via ‘people's concerts’, choral societies, brass bands, state education and festivals, he notes, a significant proportion of the population became familiar with composers including Wagner, Donizetti and Handel (especially owing to his Messiah oratorio). Driven by a ‘belief in music's efficacy as a social healer’, reformers strove for class reconciliation (p. 26) – a sharing of culture, Russell points out, that was perhaps easier than the sharing of political privilege or the proceeds of industrial capitalism (p. 64). The term ‘popular’ was used to designate not only these philanthropic endeavours to widen access to concerts, but also works with a certain ‘universality of appeal’: composers such as Beethoven, George Hopper argued in 1898, who ‘re-echo the deeper feelings of the race … pre-eminently understood the mission of music, so much so that his thoughts, like Shakespeare's, were not of an age but for all time’. ‘Popularity’, Hopper went as far as to propose, ‘even in the grossest music is in itself a proof of merit’ (Hopper Reference Hopper1898). Haweis (Reference Haweis1871, p. 517) concurred in his discussion of African American melodies, avowing that ‘nothing popular should be held beneath the attention of thoughtful people’.Footnote 14 Such opinions, however, were rare and could exist alongside contradictory passages of denunciation.

Nine years after Jevons's essay, J. Spencer Curwen – son of John Curwen, Congregational minister, educationist, abolitionist and architect of the Tonic Sol-Fa system – took up the theme of musical reform in the Contemporary Review. Proposing that music fulfilled ‘its most attractive and beneficent mission when the masses of the people enjoy it as a recreation and a solace’, Curwen reiterated that it was the social reformer's task not to lead by negation nor merely to condemn commercial amusements, but rather to replace them with superior diversions: ‘The point is, to occupy [the population] healthily; to drive out the base and carnal by quietly filling up their leisure with the lofty and the intellectual’ (Curwen Reference Curwen1887, p. 236). The best way to ‘fight the public-houses and music-halls’, he stated, was ‘by starting a counter-attraction’ (p. 241). Such ideals were part of sweeping efforts by a middle-class elite fearful of the corrupting effects of undirected leisure time: the solution, Bailey (Reference Bailey1978, pp. 5–6) argues, ‘required the building of a new social conformity’ – a play discipline equivalent to labour discipline that might ‘immunise workers against the alleged degenerations of their own culture’. Above all, Scott (Reference Scott2002, p. 64) affirms, social reformers strove for a utopian goal: the establishment of ‘a single, shared culture’. Curwen's ambition was the improvement of public taste – his title ‘The progress of popular music’ referring to practices such as singing in schools, organ recitals, brass bands, domestic music making on the concertina or accordion, amateur choirs, Eisteddfods and inexpensive concerts of classical music. These pursuits, for Curwen, constituted an authentically ‘popular’ music.

Reformers were committed to a refinement of working-class behaviour both through attention to great art and also through the effects of joining together to create music across the nation. Embracing a stance strikingly at odds with the folksong revival that would blossom in the decades to come, Curwen noted that the fallout of mass urbanisation had brought with it at least one positive outcome:

At the beginning of the century half the population was engaged in agriculture, and lived amid rural surroundings. Now only one-seventh or one-eighth is so engaged; the rest being occupied in industrial occupations, nearly all of which are carried on in towns, amid surroundings which are ugly, noisy, and often unhealthy. Thus Nature, which is man's best restorer, is out of the reach of a majority of our population … It may be added that our aggregation in towns, however much it has done to destroy the picturesqueness of life, has been distinctly favourable to musical culture, which thrives best in places where people can meet constantly and in large numbers. (Curwen Reference Curwen1887, pp. 236–7)Footnote 15

Such demographic change, however, brought with it the very aspects of mass culture that Curwen and his fellow social reformers so vociferously opposed. Noting that most urban residents found ‘their chief musical recreation in the music hall’, Curwen (Reference Curwen1887) denounced such leisure pursuits on the grounds that ‘the sole object of the proprietors is to sell their beer and spirits’ and that ‘music in these places takes its turn with ventriloquism, gymnastics, and caricature of all kinds’ (p. 245). Galvanising this outlook was the widespread fear that, in line with the ideas of heritability promulgated by Francis Galton, if certain biological faculties such as the perception of colour were not fittingly used or cultivated, they would atrophy over time and perhaps disappear altogether.Footnote 16 Heralding an analogous deterioration of listening habits and aesthetic sensitivity, the music hall posed a serious danger to the English race's future ability to benefit from the higher reaches of Western art music.

Behind what can initially appear as contempt, however, was often a genuinely democratic faith in the tastes of the multitude juxtaposed with the ideas of those in the music industry. In 1878, for example, Henry C. Lunn suggested that most ‘popular’ music was in fact the product of a condescending metropolitan imagination:

It has frequently occurred to me that those who devote themselves to providing ‘people's music’, at moderate prices, as a rule, bestow but little pains to ascertain what kind of compositions the ‘people’ really desire. Taking it for granted that popular art must be inferior art, selections intended to attract what is usually termed the ‘million’ are often made up of materials which would repel music-lovers. (Lunn Reference Lunn1878, p. 660)

Retaining the pervasive idea that a taste for Western classical music was ‘elevated’ in comparison with a commercial domain, Lunn nevertheless sought to destabilise the ways in which music was employed to validate social distinctions:

At the last Gloucester Festival … when the fashionably dressed promenaders were about to re-enter the cathedral for the second part of the morning's performance I was addressed by an earnest and intelligent-looking working-man, who inquired whether I thought he should be able to hear many of the choruses in the ‘Hymn of Praise’ outside. Finding by my reply that I sympathised with him, he began to enlarge upon the wondrous beauties of the choral pieces he had already heard; but it was not until I asked him whether he would like to be inside the cathedral that the weight of his rough eloquence touched me. ‘Like to be there, sir!’ he said, calmly and with not a tinge of bitter feeling in the tone of his voice; ‘yes, if I could get a corner where my poor dress would not be seen, and so would many like me. But the Festival's not for such as us[’] … The opinion expressed by this man I found fairly represented the class to which he belonged, for in conversation with many others in the town it was often observed to me not only that good music well done was shut out from ‘such as them’, but that bad music ill done was presumed to be the kind of entertainment they craved for. (Lunn Reference Lunn1878)

In other words, Lunn was arguing for the taste polarity of highbrow/lowbrow to be untethered from its implied class-based concomitant. The schism he saw instead involved a contrast between respectful lovers of music and those who showed no interest in the art form and treated concerts as social occasions – ‘loungers’ who saw music as a ‘secondary attraction’ to quaffing champagne (p. 661).

The only barrier to the enjoyment of classical music by all, Lunn (Reference Lunn1878) stressed, was that performances of the great works were ‘reserved for those who can afford to pay for such luxuries’. Whereas musical recreations allied with a reformist agenda attempted to broaden public access by reducing admission costs, as Scott (Reference Scott2002, p. 61) notes, ticket pricing was frequently used ‘to produce a class hierarchy of concerts’ – buttressing distinctions between classes and within class fractions. Reading against the grain, Lunn's vignette is an example of this desire for status reinforcement: his ventriloquised portrait of an ‘earnest and intelligent-looking working-man’, suitably deferential and lacking in animosity, is a portrait of working-class respectability depicted as the obeisant mirror of bourgeois decorum. Given the relative opaqueness of working-class life for many commentators, Bailey (Reference Bailey1998, pp. 43–4) points out, such reassuring visions answered a yearning for ‘conceptual order and stability’, furnishing ‘proof of the middle-class capacity to remake society in their own image’. Such encounters, however, were multifaceted: Lunn's interlocutor, we must assume, was performing a role in full knowledge of class differentials and expectations – a role that, later on, might well be cast off or modified. As Bailey (Reference Bailey1998) proposes, working-class respectability is best seen as a ‘situational’ identity that labourers could adopt for ‘instrumental or calculative’ ends (pp. 30, 39). The notion that no deterministic relationship existed between class, affluence, and aesthetic preference was nevertheless a powerful insight. An article on ‘Popular Entertainments’ from 1865, for example, noted that in Britain ‘even in the same classes very different tastes prevail … we may see artizans and grisettes at the high-class drama, and men of a very superior grade at the music-halls’; ‘plenty of money and fine clothes’, it pointed out, ‘give no assurance of mental refinement’ (Anon. 1865, pp. 327–8).

Likewise, Curwen noted that ‘a distinction must be drawn between the West-end music-halls, which, it is to be feared, are wholly bad, and those in the industrial quarters of East and South London, which, bad as they are, are attended by a large number of honest working folk’ (Curwen Reference Curwen1887, pp. 244–5). The latter, an article in the National Observer made clear, was the ‘popular’ music hall; the former was a debauched and capitalised offshoot frequented by the errant petty bourgeois. In these well-appointed halls, voguish variety entertainment was only ‘half appreciated by a listless, languid audience, comfortably fed and well-seated, which asks no more than something that shall fleet the time between dinner and bed agreeably’ (Anon. 1894a, pp. 536–7). In contrast, this article continued, was a more authentic realm:

We are not at all sure that the popular halls lose anything that is worth saving by the comparative poverty of their decorations. The interest of the whole house is focused upon the stage. This compels the most indolent actor to throw all his energy into his work; he dares not lose the attention of the audience, and the audience will very soon find him out should he condescend to trickery that he may win applause thereby. And it cares for very little that is not human nature. (Anon. 1894a, p. 537)

These houses, it remarked, were patronised by a working-class audience of ‘relentless critics’ ‘bred to the music-hall’ who ‘set no restraint upon their feelings, no measure upon their applause or disapproval’ (Anon. 1894a). Such positive views of London's working class and other civil or conscientious labouring figures, we should not forget, were also complicit in promoting an attentive, disciplined and governable populace as a bulwark against the combined threats of Chartism, industrial militancy, pauperism and moral degeneracy.Footnote 17 An elevation of the East End, moreover, often served to articulate a gendered opposition to what was felt to be the ‘emasculating forces’ of mass consumer culture (Faulk Reference Faulk2004, p. 130; see Huyssen Reference Huyssen1988).

Similarly gendered polarisations existed within the realm of commercial sheet music – oppositions relegating the licentious excesses of West End music halls in favour of virtuous material by more respectable authors. A review of Dresden China and Other Songs by the prolific Oxford-educated songwriter and barrister Frederic E. Weatherly, for example, praised the ‘honest manly sentiment’ of his lyrics as an antidote to ‘the baneful effects of the rowdy popular Muse’ (Anon. 1880, p. 756). Despite also dubbing Weatherly's songs ‘popular’, the reviewer drew a distinction between two different sets of writers peddling their wares:

First, there are the music-hall bards. These songsters stir the great heart of the city folks, as it were with the sound of a trumpet. ‘To arms, to arms, to arms, they cry’, in the name of Jingo. They breathe of heady delights, of war, of wine, of the popular Aphrodite … The ethical analysis of these popular songs produces distressing results. The residuum of each composition is a deposit of solid unalloyed vulgarity. The lover of rowdy popular songs confesses himself to be a mean admirer of mean things, of a cheap, noisy, flashy sort of life, of a constant state of alcoholic excitement. Fancy paints him in a magenta necktie, with dirty yellow gloves, with a book on the Derby, with a stick that inexpensively imitates the last fashion but two. (Anon. 1880, p. 755)

Such material betokened a lifestyle of unrefined Dionysian revelry involving a cheap imitation of gentility: ‘if popular songs make popular characters’, the author speculated, ‘we may expect a ghastly generation of dingy gommeux as a consequence of fast music-hall ditties’ (Anon. 1880). These figures were generally young, lower middle-class clerks – a new and socially aspirational grouping vilified by the literary intelligentsia and considered especially vulnerable ‘to the temptations of fast company’ (Bailey Reference Bailey1978, p. 93; see Carey Reference Carey1992). The swell's ‘admiration for wealth and status’ was nonetheless double edged, staging a burlesque of Victorian morality by ‘celebrating excess and idleness’ (Scott Reference Scott2002, p. 71). The music hall, Bailey (Reference Bailey1998, pp. 8–9) argues, functioned as a ‘laboratory of style’ in which both its patrons and performers could engage in a kind of ‘cultural cross-dressing’ – becoming ‘transient tenants of various and competing subject positions, each a multiple-self unevenly defined in collusive antithesis with the dominant cultural order’.

In contrast, this review stated, was a category of more upstanding material, revealing a moral disjunction between two variants of middle-class identity:

There is another class of popular song, which is full of tender sentiment and domestic affection, and bluff, honest pleasure in a laborious life. This sort, if one may judge by the milder kind of drawing-room ditty, and by the airs of the barrel-organ-grinders, is as popular among the respectable middle classes as ‘Champagne Charley’ among the jeunesse cuivrée of London. (Anon. 1880, pp. 755–6)

Imbued with ‘kindliness’ and ‘gentle melancholy’ (Anon. 1880), such material promised order, temperance and integrity in the face of unprecedented socio-economic change. Providing a masculine counterbalance to the corrupting effects of sybaritic urban dandyism, these songs assured class distinctions that the swell's parodic gestures undermined. Not all commentators, however, took such an intolerant view of these new facets of Victorian mass entertainment – one writer in the Saturday Review urging its readers to treat the music hall with a ‘courteous openmindedness’ given that it was ‘as certain, as serious, a fact as democracy’ (Anon. 1894b).

Towards a new cartography

Although it is beyond the scope of the present article to trace such a process in detail, we might surmise that in the wake of modernism's aesthetic polarisations – the apex of Huyssen's ‘Great Divide’ – this second way of viewing the popular as a channel for social reform is gradually eclipsed by the first, which remains with us today as a way of identifying the products, principles and dangers of advanced neoliberalism. Indicative of much Leftist discourse on contemporary mass culture, for instance, is an impromptu speech made at the July 2016 WXPN XPONENTIAL music festival in Camden, New Jersey by Josh Tillman, alias Father John Misty, who addressed his audience volubly amid shouts of ‘you're right!’ and ‘preach it!’:

Do you people realize we have an entertaining tyrant happening right now? … I always thought that it was gonna look way more sophisticated than this when fucking evil happened, when the collective consciousness was so numb and so fucking sated and so gorged on entertainment … I cannot play ‘Bored in the USA’ for you right now. Because guess what – I soft-shoed that shit into existence by going ‘no no no, look over here, put your self-awareness on, it will never actually be that bad because we're too smart’. And while we were looking in that direction stupidity just fucking runs the world because entertainment is stupid. Do you guys realize that? At the core, entertainment is stupid.Footnote 18

The tyrant, of course, was Donald J. Trump, the populist Republican candidate soon to be elected 45th President of the USA. As we have seen from the period under discussion, such attacks on the popular are not new: in this Adornian reading mass culture functions as escapism or as a social narcotic, lulling the population into a state of political negligence. This view nevertheless harbours a paradox for radicals in which the popular exemplifies something to be concurrently distrusted (as the signifier of a vulgar, mindless and potentially fascist mob) and embraced (for its latent revolutionary potential). This contradiction is the enigma at the heart of the popular: a mass imagined as simultaneously docile and seditious.

Popular culture, as Bailey (Reference Bailey1998, pp. 10–11) attests, is ‘a sprawling hybrid’ with a dynamic constituency ‘not coterminous with any single class’: its meanings, he writes, ‘like its satisfactions, are ambiguous and far from always benign, mixing the reactionary and conservative with the potentially subversive’. Definitions of popular music thus exist within a litany of contradictory ideas. During the epoch in which urban mass culture arises as a constituent of modernity, we can discern at least 10 different ways in which the term was used: (1) as an indication of commercialism and vulgarity that portended the degeneration of modern civilisation; (2) as a positive depiction of vernacular, amateur or domestic music making; (3) as a descriptor for low-priced editions and performances of works by composers of Western art music; (4) as proof of merit in itself; (5) as a presumption of what the masses desired in the commercial imagination of those in the music industry; (6) as the real and unruly aesthetic preferences of the population as a whole; (7) as whatever happened to be valued by different communities of taste; (8) as the sign of something universal or in touch with humanity; (9) as a way of identifying folksong in opposition to literary or commercial products; and (10) as a way to construe lower-class respectability. The idea was simultaneously used to stage and articulate disputes between what was perceived to be reputable and genuine and what was perceived to be artificial and debased, creating a cascade of binary oppositions: ‘low’ commercial music vs. ‘high’ classical music; ‘degenerate’ music vs. ‘organic’ folksong; ‘vulgar’ entertainment vs. ‘manly’ sentimental song; and ‘decadent’ middle-class music halls vs. ‘honest’ working-class music halls. Rarely, however, did commentators aim to interpret the popular on its own terms; rather, it was always imbricated with aesthetic and moral judgements and a concomitant desire to effect change.

The popular, in short, is a floating signifier with the potential to reference mutually opposing ideas. Underlying all these conflicting polarities and definitions was the issue of whether popular material adversely influenced or merely reflected popular views and tastes: for social reformers, neither option was particularly palatable, and both were often equivocally interlaced. In Britain, these figures saw leisure as the ideal conduit for an authoritarian substitution of ‘good’ music for ‘bad’ in the hope of improving the public's supposedly delinquent tastes – the symptom of an anxious elite attempting to edify and unite a mass populace according to hierarchical ideals that reproduced their own sensibilities and aesthetic values. The issue of race only compounded such issues, given that blackness was ensnared with a vision of the popular as base in its recourse to ‘exotic’, ‘primitive’ or even ‘hysterical’ rhythms. Other writers, however, trusted the public's preferences to such a degree that the solution to reform lay simply in granting the masses access to an elevated sphere too often rendered inaccessible by cost or etiquette. The meaning of ‘popular’ in popular music thus altered according to how the word was understood as a political signifier: although it could be employed to represent depravity, in other contexts it signified democracy. During this turbulent era, in other words, we witness a discursive conflict break out over the significance of popular music – a fight that reformers ultimately lose in their quixotic attempts to wrest the idea of the popular from an equivalence with commerce and immorality, and inscribe it with positive or egalitarian connotations. The phrase must therefore be read in light of the shifting, paradoxical and politically charged motivations behind its various appearances. How is it being used and why? By whom? In reference to material culture, tastes, practices or particular social groupings? In condemnation or praise?

It is this extraordinary ability of the term ‘popular’ to refer equally to Beethoven, bhagṛā, and blackface minstrelsy that should impel us to establish new conversations within musicology – transdisciplinary dialogues attentive not only to the fluctuating musical habits of those deemed ‘the people’, but also to those with the privilege of determining who ‘the people’ are. One approach that would benefit such a remapping of the cultural landscape is an increased attention to individual acts of engagement with music – whether high or low, countercultural or mainstream. Instead of attempting to decide what popular music is, we might turn our attention towards the praxis of reception. In his analysis of everyday life, for example, Michel de Certeau encourages looking into a hidden kind of poiēsis:

the analysis of the images broadcast by television (representation) and of the time spent watching television (behavior) should be complemented by a study of what the cultural consumer ‘makes’ or ‘does’ during this time and with these images. The same goes for the use of urban space, the products purchased in the supermarket, the stories and legends distributed by the newspapers. (de Certeau Reference de Certeau and Rendall1984, p. xii)

Consumers, de Certeau insists, are ‘silent discoverers of their own paths in the jungle of functionalist rationality’ (p. xviii). Recuperating these fragmentary, unpredictable ‘tactics’ of re-appropriation would grant people an agency denied by theoretical models that imply passivity, homogeneity and domination – while acknowledging that such bricolage occurs within modernity's overarching ‘strategies’ of power and coercion. Reimagining our field of study according to these small but significant acts would provide the material for a new cartography of the popular.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to Delia Casadei, Nick Cook, James Gabrillo, Oskar Cox Jensen, and Chris Townsend for their thoughts on an early draft. I’m also indebted to the anonymous reviewers for this journal, as well as those who offered comments after my papers at University College Cork and New College, Oxford.