Introduction

Over the past decade, the quality of hospice care within the United States has emerged as a public health concern (Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, Gallo and Bradley2004; Perry and Stone Reference Perry and Stone2011; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Beltran and Gammonley2021). Existing studies have unearthed substantial disparities in the quality of hospice care services (Parast et al. Reference Parast, Elliott and Hambarsoomian2018a, Reference Parast, Haas and Tolpadi2018b). In response to these quality concerns, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has taken proactive measures by publishing Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) scores on their Hospice Compare website (CMS 2021). With less than one-third of California hospices having CAHPS scores reported on Hospice Compare (Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Cardenas and Singleton2021), there exists an untapped, rich resource of hospice quality data in open-ended online reviews that has yet to be explored, categorized into positive and negative reviews, and analyzed thematically.

Having different types of quality assessments, including both open-ended reviews and close-ended surveys, is essential for a comprehensive understanding of hospice care quality. While close-ended surveys provide standardized and quantifiable data, open-ended reviews add depth, context, and individual perspectives. Together, these assessments offer a more holistic view of caregiver experiences, enabling hospices to identify strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement in their services. By combining quantitative data from surveys with qualitative insights from open-ended reviews, hospices can make more informed decisions and implement targeted improvements to enhance the overall quality of care provided to patients and their families.

Advocacy for hospice consumers is bolstered not only by the Hospice Compare website but also by the burgeoning interest in online consumer health service reviews, seen on platforms like Yelp and Google (Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Cardenas and Singleton2021; Raths Reference Raths2016; Scotty 2018; Yelp 2022). An extensive literature review found that 1 study compared open-ended reviews with closed-ended Hospice CAHPS scores (Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Cardenas and Singleton2021). Rahman and team discovered that themes emerging from Yelp were broader and more varied compared to those on Hospice Compare. Nonetheless, they didn’t contrast positive reviews with negative ones. We did find a study that examine only the negative reviews from large hospices (Brereton et al. Reference Brereton, Matlock and Fitzgerald2020). In our investigative process, we pursued a caring model as a guiding framework.

Watson’s theory of human caring

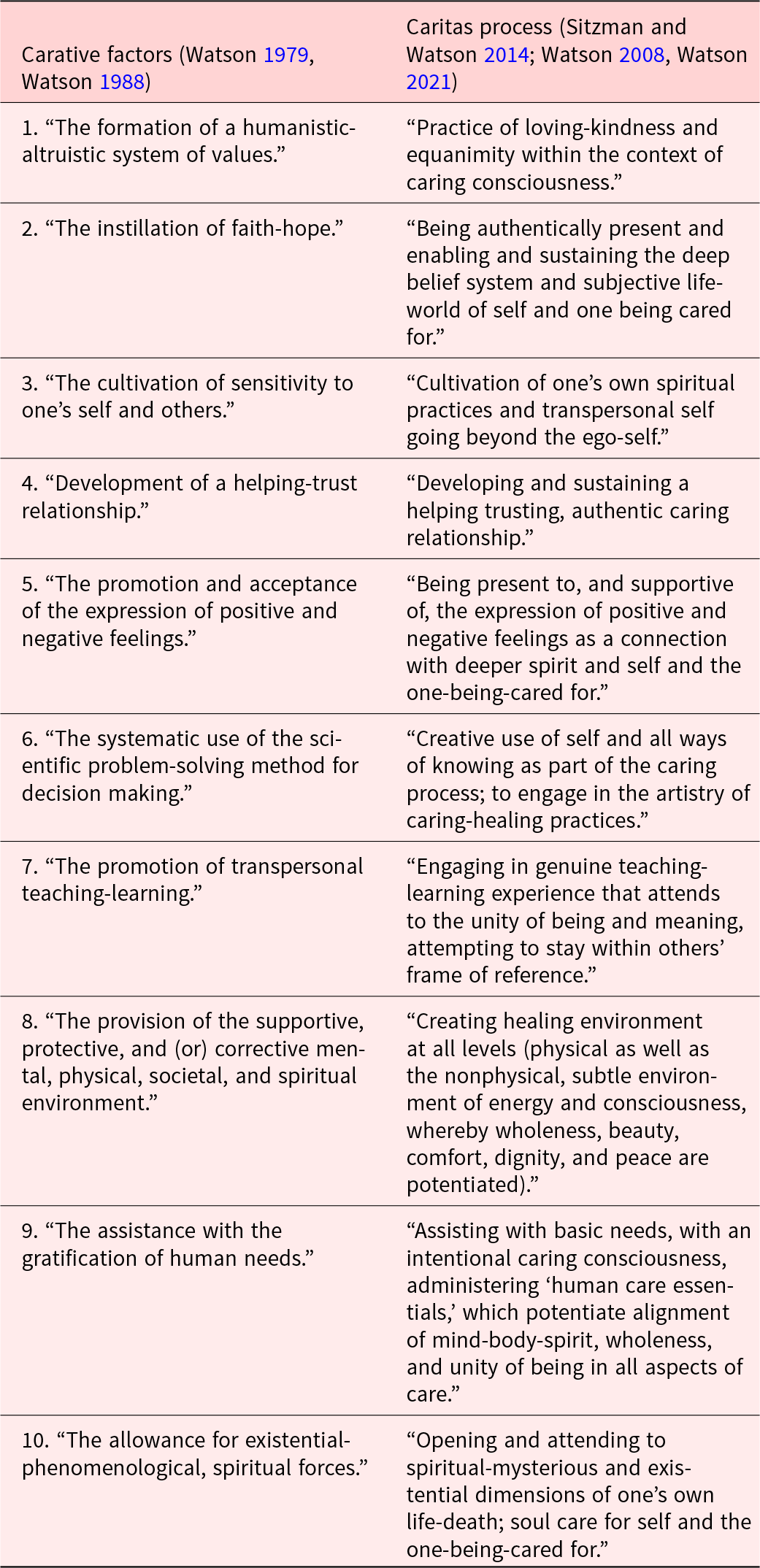

Jean Watson’s theory of caring (Watson Reference Watson1979, Reference Watson1988) has clear relevance to the hospice care context (CMS 2022). Watson urged, “care and love are the most universal, the most tremendous, and the most mysterious of cosmic forces: they comprise the primal universal psychic energy” (Watson Reference Watson1988, 33–34). Table 1 displays Watson’s 10 carative factors as the basis of health care processes (Watson Reference Watson1979, Reference Watson1988). Employing Watson’s human-valuing perspective in conjunction with our thematic analysis approach enabled caregivers to articulate their personalized interpretations of what hospice care means to them. Taking a user experience approach, this study’s purpose was to develop a method and model of hospice quality assessment from natural language processing (NLP) of online caregiver reviews using Watson’s carative model as an interpretative lens for understanding decedent caregiver needs.

Table 1. Watson’s carative factors and caritas processes

Method

A retrospective user experience approach was taken leveraging thematic sentiment analysis. Human coding was used to identify initial topics. Inspired to delve directly into expressed hospice experiences, our preliminary pilot process was modeled after the “read-first” approach recommended by Rahman and colleagues. Utilizing a grounded theory methodology, their research team engaged human coders to interpret and categorize Yelp reviews of US hospices (Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Cardenas and Singleton2021). Our objective was to unearth both positive and negative themes presenting in these reviews, and subsequently, to decipher what these combined insights might divulge about hospice quality.

Complementing CAHPS surveys with open-ended reviews from hospice caregivers presents several advantages. First, such reviews allow caregivers to articulate their experiences and concerns unconstrained by a preset question set, facilitating the identification of issues potentially overlooked by closed-ended surveys. Second, they yield rich, contextually detailed information, as caregivers can express their perspectives, emotions, and personal narratives, enriching our understanding of their experiences. Lastly, these open-ended reviews provide personalized feedback, enabling caregivers to voice their unique needs, expectations, and preferences, thus identifying areas for service customization and enhancement.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Given the scarcity of online reviews for certain hospices, we sourced hospices from the Lexis-Nexis list of the 50 largest hospices (Shabbir Reference Shabbir2021) with the aim of acquiring a sufficient number of reviews to form a representative sample of hospice experiences. We opted for the largest hospices to ensure the possibility of locating 30 reviews per hospice. The research team, consisting of 3 members, each undertook the task of finding 30 reviews for 5 for-profit hospices and 5 non-profit hospices, yielding a total of 15 hospices for each category. Following the review of these pilot responses, we identified themes and compiled a list of 25 initial themes.

To maintain the integrity and representation of caregiver reviews, we screened reviews based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Reviews were excluded on the following grounds: first, if they were submitted by caregivers whose loved ones did not meet Medicare qualifications for admission, and second, in light of the information suggesting that around 10–25% of hospice reviews on Google or Yelp could potentially be fraudulent or authored by the hospice’s own personnel (Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, Cardenas and Singleton2021; Scotty 2018; Yelp 2022), we excluded reviews with no narrative component. Google and Yelp both use artificial intelligence to remove reviews likely to be fake (Ranard et al. Reference Ranard, Werner and Antanavicius2016). Third, we dismissed reviews originating from non-caregivers. Following these quality-based exclusions, we established our inclusion criterion, which specified that the reviews must come solely from caregivers of deceased enrollees, spanning a 6-year period from 2013 to 2023.

Analysis

Human theme coding

In our pilot sample, we utilized thematic analysis, informed by Watson’s carative factors, to identify themes and categories within the reviews. A team consisting of 2 trained research assistants and a faculty member, who is also an experienced hospice professional, independently performed open coding of the reviews. Following this, a comparative analysis was carried out where team members discussed the identified themes side by side. Our operational definitions for each theme underwent iterative refinement from their original formulations. Additionally, we tallied the frequency of each theme’s occurrence in 1–2-star and 4–5-star reviews, allowing for a more nuanced comprehension of themes predominantly associated with either positive or negative hospice care experiences.

Machine theme coding

We aimed to obtain a stratified sample, weighted by hospice size, mirroring the daily census of hospice enrollees among the largest hospices in the United States. To ensure a nationally representative sample of US hospice providers based on active hospice census, we set sample size criteria. For smaller hospices, comprising less than .30% of the hospice market capitalization, we aimed to collect a minimum of 30 reviews. Medium-sized hospices, representing .30–.50% of the market, required 50 reviews. Larger hospices, accounting for 0.50–1.0% of the market, necessitated 100 reviews. Lastly, for the largest hospices, those surpassing 1.0% of the market, we aimed for 200–250 reviews.

Sentiment analysis was performed on hospice reviews using a Google’s NLP API (Blei et al. Reference Blei, Ng and Jordan2013; Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Eichstaedt and Kern2013; Schwartz and Ungar Reference Schwartz and Ungar2015). The dataset was preprocessed to remove stop words, punctuations, and Uniform Resource Locators. The remaining text was tokenized and converted to lowercase for consistency. We then used Google Cloud Natural Language to classify the sentiment of each review.

Sentiment scores ranged from –1 to 1, with –1 indicating extremely negative sentiment, 0 indicating neutral sentiment, and 1 indicating extremely positive sentiment. A sentiment score between –.25 and .25 is considered neutral, between –.25 and –.5 or .25 and .5 is mildly negative or positive, and below –.5 or above .5 is highly negative or positive. Magnitude scores ranged from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating a lack of emotion or intensity, and 1 indicating strong emotional intensity. A magnitude score between .1 and .3 is considered low, between .3 and .7 is moderate, and >.7 is high (Cambria and Hussain Reference Cambria, Hussain, Hussain, Chang and Meethan2012).

We employed both manual and automated methods to discern the most recurrent themes within the reviews. Initially, a subset of the reviews was manually read and common themes were identified. Subsequently, a text mining approach was utilized to pinpoint additional themes automatically. This text mining was executed using the Python programming language along with the Natural Language Toolkit library, utilizing techniques like tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, and named entity recognition. The sentiment analysis of the hospice reviews led to the identification of the top 25 themes based on their frequency of occurrence. For each theme, we computed both the sentiment and magnitude scores.

Thematic co-occurrence

To develop a model for overall hospice quality, we ran co-occurrence analysis. We then calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between the 2 matrices to determine the association between positive and negative themes in the reviews. To test the significance of the correlation coefficient, we conducted a permutation test by randomly shuffling the positive and negative themes and recalculating the correlation coefficient 10,000 times. We then compared the observed correlation coefficient with the distribution of correlation coefficients obtained from the permutation test to calculate a p-value.

Results

Pilot sample – theme identification and prevalence

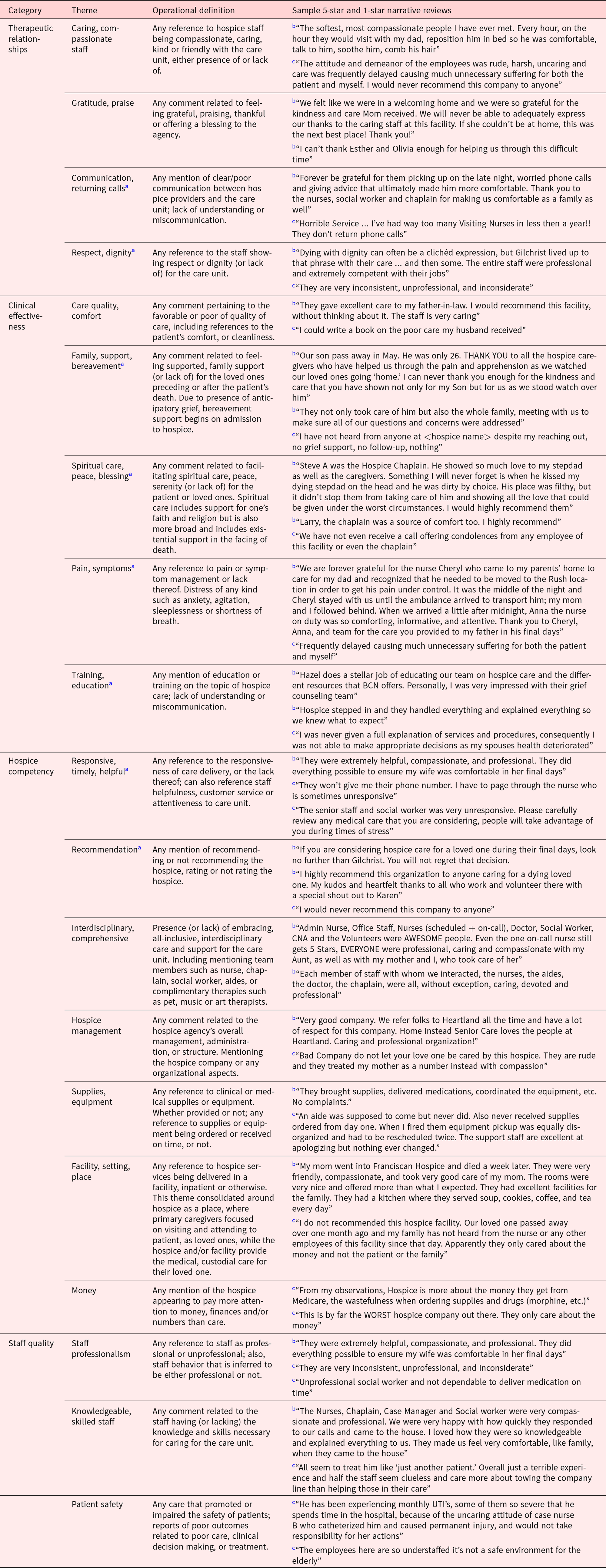

There were 683 positive reviews (66.96%) and 337 negative reviews (33.04%) in the pilot sample. From the initial 25 themes, our team converged on 20 themes, which we arranged into 4 main categories: therapeutic relationships, clinical effectiveness, staff quality, and hospice competency. Table 2 shows each category, its associated themes, operational definitions, and sample reviews. Table 3 illustrates that through our identification process, we discovered 8 review themes that were directly linked with all 8 CAHPS indicators and their corresponding Watson’s carative factor (Watson Reference Watson1979, Reference Watson1988). To maintain conciseness, our report prioritizes the 10 most dominant themes along with those associated with the 8 CAHPS measures.

Table 2. Review themes – categories, themes, operational definitions, and sample reviews

Eight of our identified review themes were directly associated with all (8 of 8) caregiver-survey measures published in CAHPS scores.

a This coded theme is directly addressed by 1 of 8 items in the Hospice CAHPS survey to be posted on CMS’s Hospice Compare.

b Five-star review.

c One-star review.

Table 3. Comparison of theme frequencies in online hospice reviews by star rating with equivalent CAHPS indicators (n = 1020)

a Review themes begin with caring, compassionate staff. Positive reviews are 4–5 stars, negative reviews are 1–2 stars.

b Two global CAHPS measures – “Recommend” and “Rate the hospice.”

Review stars mean for this pilot sample = 3.71.

Therapeutic relationships

Four themes comprised the therapeutic relationship category. Table 3 illustrates that through our identification process, we discovered 8 review themes that were directly linked with all 8 CAHPS indicators. The most frequently mentioned theme was caring, compassionate staff, identified in over half (46.22%) of all reviews. This theme comprised the nature of patients’ care and whether staff treated patients and loved ones with kindness and compassion.

Gratitude, praise (39.19%) was the third-most frequently mentioned theme. Communication (also a CAHPS measure) was the seventh-most frequently identified theme in 24.56% of all reviews. Poor communication was the most common grievance in negative (1-2 star) reviews. Respect, dignity (also a CAHPS measure) was the seventh least mentioned theme in online reviews (14.94% of all reviews).

Clinical effectiveness

This category comprised 6 related themes. The second most prevalence theme was care quality and comfort (45.29%). Positive (4-5 star) reviews had significantly more proclamations of high care quality (40.45%) than protests of inadequate care quality in negative reviews (34.90%).

The theme of spiritual care, peace, and blessing (14.32%, also a related CAHPS measure) captures values regarding worldview, religion, faith, and peace at end-of-life. Positive reviews (16.13%) had statistically significant more praises for spiritual care than laments in negative reviews (7.16%). Pain and symptom management (also a CAHPS measure) is related to whether the patient experienced pain or other symptoms and whether these were controlled or managed (12.43%).

Emotional, bereavement, family support (also a CAHPS measure) was the fifth most common theme (26.53%). Positive reviews (27.18%) had statistically significant more declarations of emotional support than concerns of nonsupport in negative reviews (18.97%). Education or training (also a CAHPS measure) was the fourth least mentioned theme in online reviews (9.50%).

Hospice competency

Four themes comprised this category. The fourth-most frequent theme in this study, responsive, timely, or helpful (also a CAHPS measure), was identified in 35.49%. Reviewers were more likely to report on low responsiveness than its presence. Negative reviews (37.95%) had statistically significant more mentions of low responsiveness than positive reviews (25.14%). Like the closely related communication theme, reviewers were likelier to report poor responsiveness in negative reviews than commend good communication in positive ones.

The sixth-most prevalent theme in this study is recommending (or not recommending) the hospice, as identified in 26.15% of the online reviews. This theme (also a CAHPS measure) is a global hospice quality measure like the hospice rating. Interdisciplinary and comprehensiveness of hospice services were identified as the eighth most common theme (22.44%). This theme concerned whether the care was interdisciplinary and other services expected of hospice providers. Interdisciplinary and comprehensive care was routine in positive reviews (35.92%) yet rare in negative reviews (11.46%). Hospice management (17.95%) was a theme in this study. The reviewer’s comments related to how well or poorly the agency seemed to have been managed. Some comments pertained to problems with staffing, billing, and organization.

Staff quality

This category comprised 3 themes. Comments in this category focused on staff professionalism (21.74%) and appropriate care during visits. Complaints about staff professionalism were more prevalent in negative reviews (32.94%) than commendations on the theme in positive reviews (14.01%). Eight review themes represent the 8 CAHPS score indicators (see Table 3). The recommending theme is equivalent to the 2 global CAHPS measures of recommending and rating the hospice.

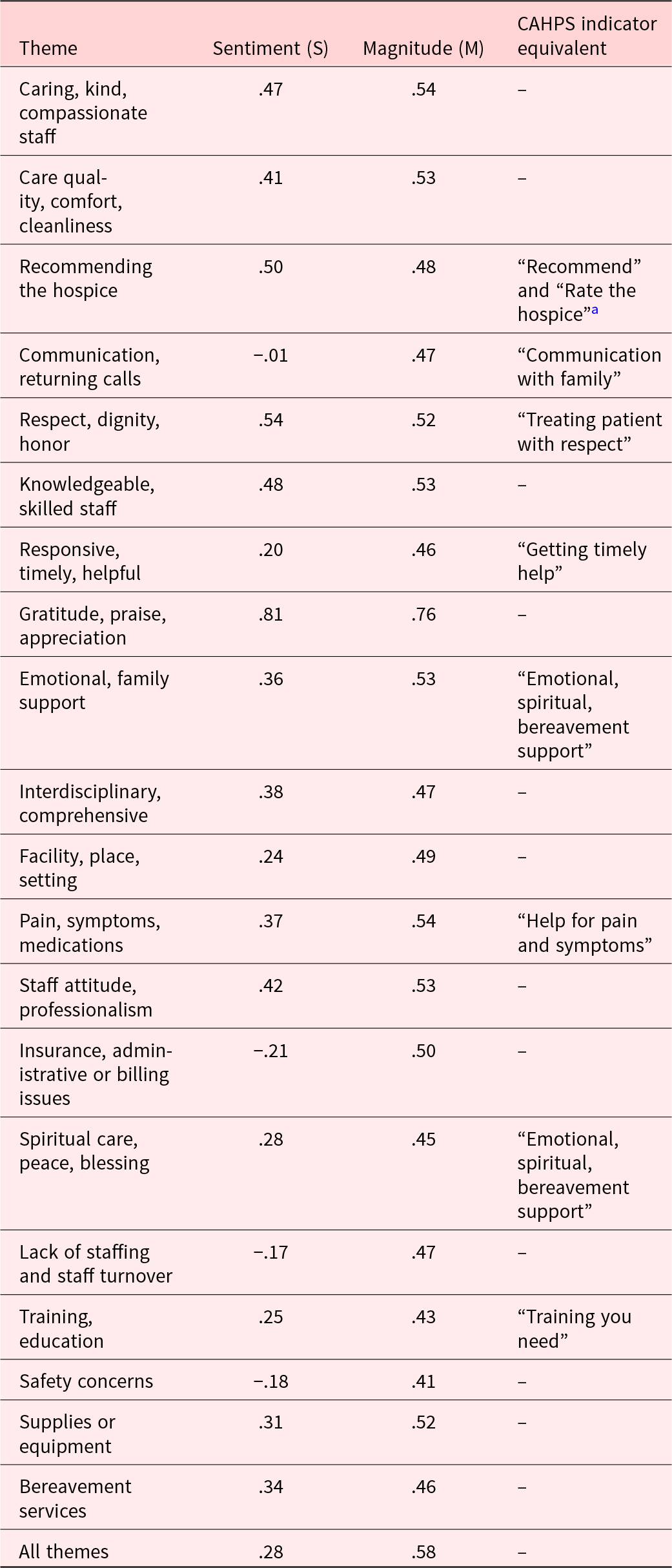

Study sample – topic consolidation and sentiment findings

We required a hospice to have at least 30 reviews for inclusion, and 47 of the 50 hospices (94%) reviewed met this criterion. Solamor Hospice, Kaiser Permanente, and Hospice Advantage did not meet this criterion and thus were excluded. Also, we discovered that Hospice Advantage was acquired by Compassus in 2015. Compassus did meet this criterion and thus was included. With the LexisNexis top 100 list and to bring the total to 50, we then added the next 3 hospices Hope Healthcare of Rhode Island (51st largest), Hospice of Wake County–Transition LifeCare (52nd), and Hospice Care Network, New York (53rd). The average number of reviews per hospice was 69 among the 3393 total reviews.

We compiled and analyzed the reviews for machine coding using Google Cloud NLP. We refined our themes after the pilot and before the study sample analysis, and the themes of Hospice management and Money were combined into Insurance, administrative or billing. Pain, symptoms and medications were consolidated into Pain, symptoms, medications. Bereavement services was broken out as a separate theme; Lack of staffing was added.

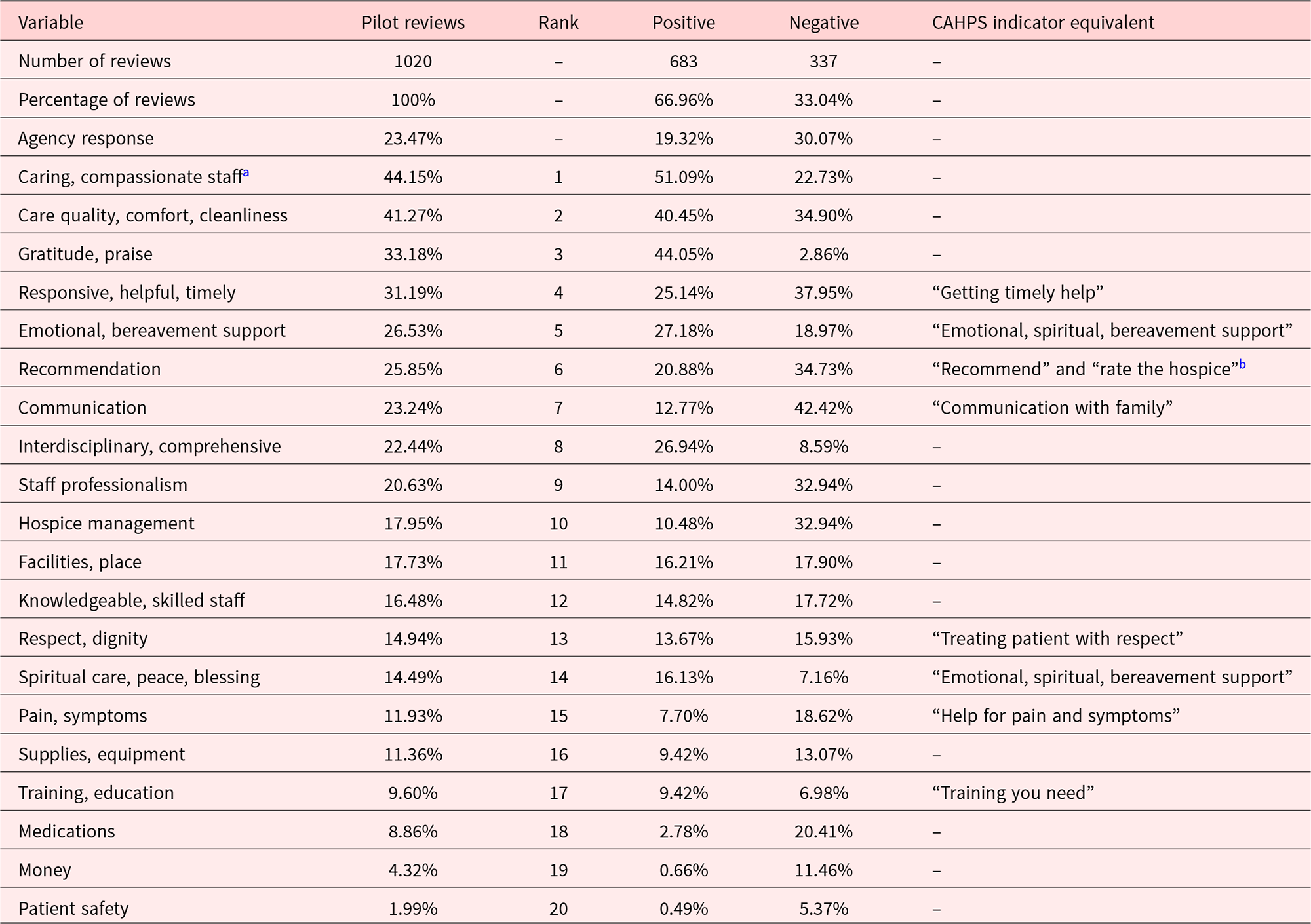

In Table 4, the findings among the study sample (n = 3393) were similar to the above findings in the pilot sample (n = 1020). Besides Gratitude, praise, with its inherent positive sentiment, the themes with the highest positive sentiments (S) and magnitudes (M) were Caring, kind, and compassionate staff (S = +.47, M = .56), and Care quality, comfort, and cleanliness (S = +.41, M = .55). Other themes following with moderate-to-high positive sentiment and moderate magnitude were Treating the patient with respect (S = + .54, M = .52); Help for pain and symptoms (S = +.37, M = .52); and Emotional, spiritual, bereavement support (S = +.38, M = .51). Lowest sentiment scores were Insurance, administrative or billing (S = – .21, M = .50); Lack of staffing (S = –.17, M = .47); Communication with the family (S = – .01, M = .47); Getting timely help (S = .20, M = .46); and Training you need (S = .25, M = .43).

Table 4. Sentiment analysis of online hospice reviews and equivalent CAHPS indicators (n = 3393)

a Two global CAHPS measures – “Recommend” and “Rate the hospice.”

Review stars mean for this pilot sample = 3.68.

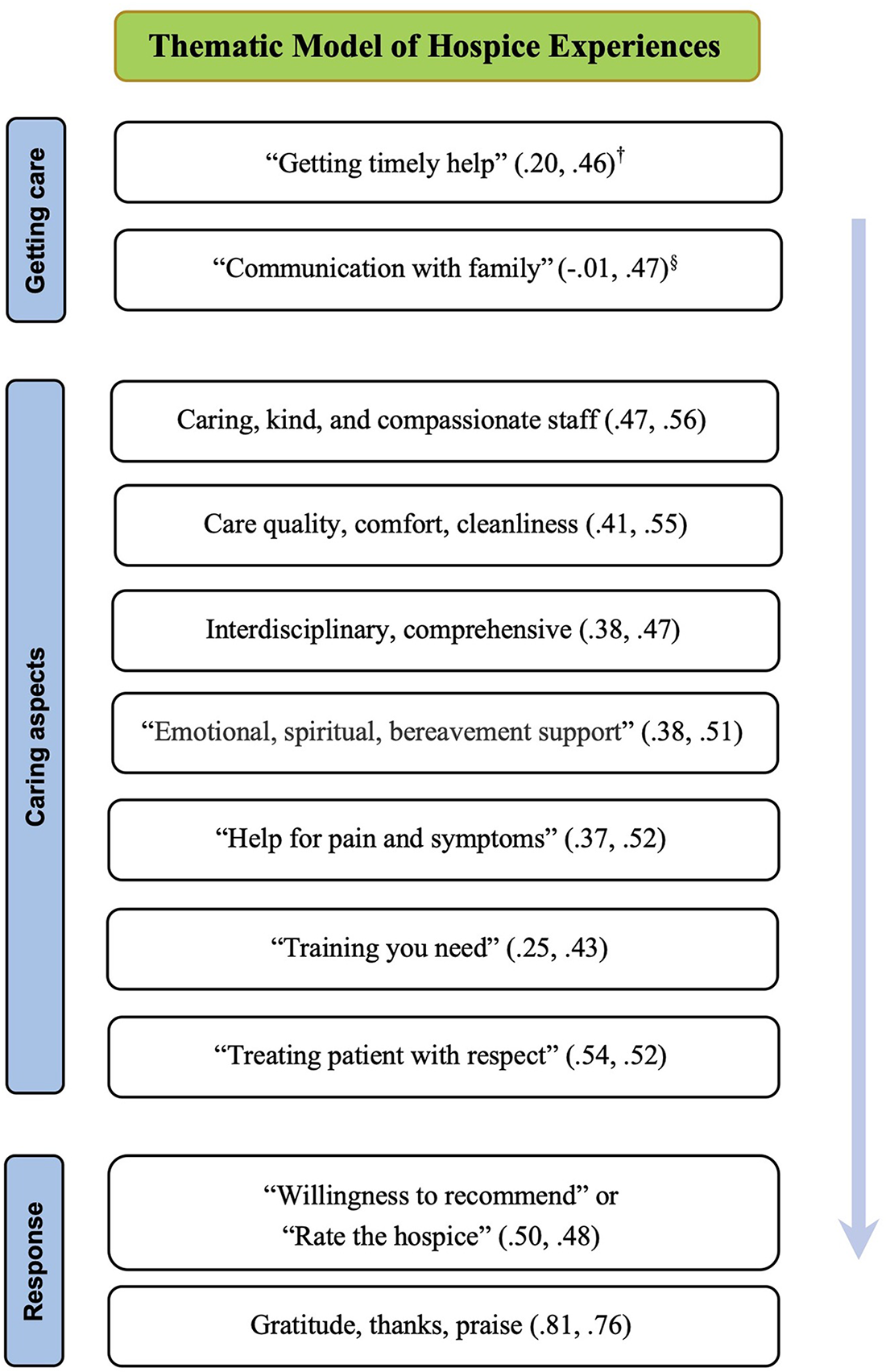

Figure 1 illuminates key thematic findings of this study through a theme flow diagram. The 8 most prominent themes from the sentiment analysis were the same 8 themes from the human coding in the pilot study. Two themes capture the process of getting care: Getting timely help and Communication with family. Then 7 themes are the caring aspects. Emotional, spiritual, bereavement support (for patients and families) were combined into 1 variable for this final model analysis. Finally, 2 themes capture the response to caring aspects: Gratitude, praise and Willingness to recommend or rating the hospice. Patient safety, though important, was a rarely mentioned topic (1.99%) and so was not included in the final thematic model.

Figure 1. Thematic Model of Hospice Experiences

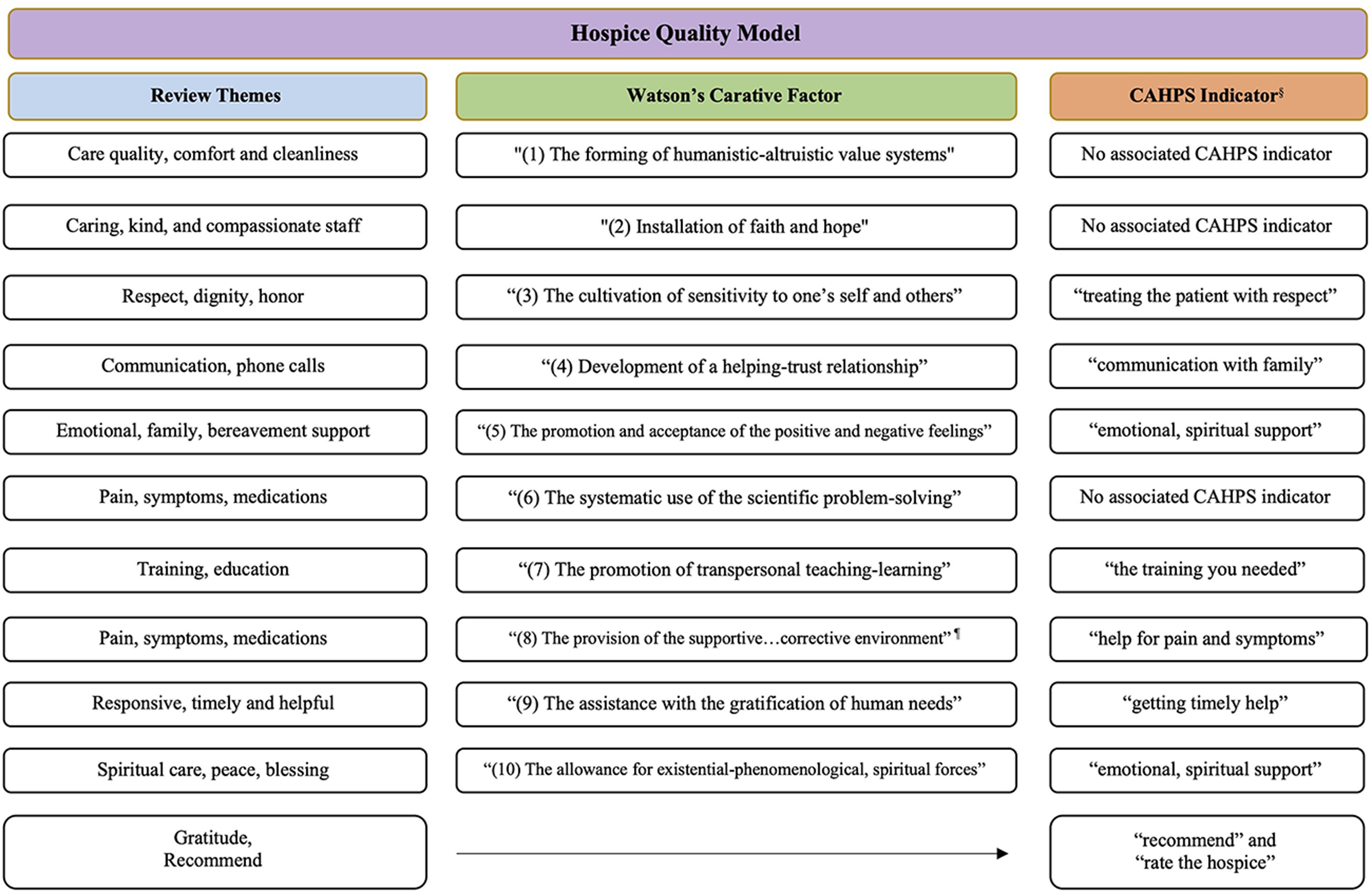

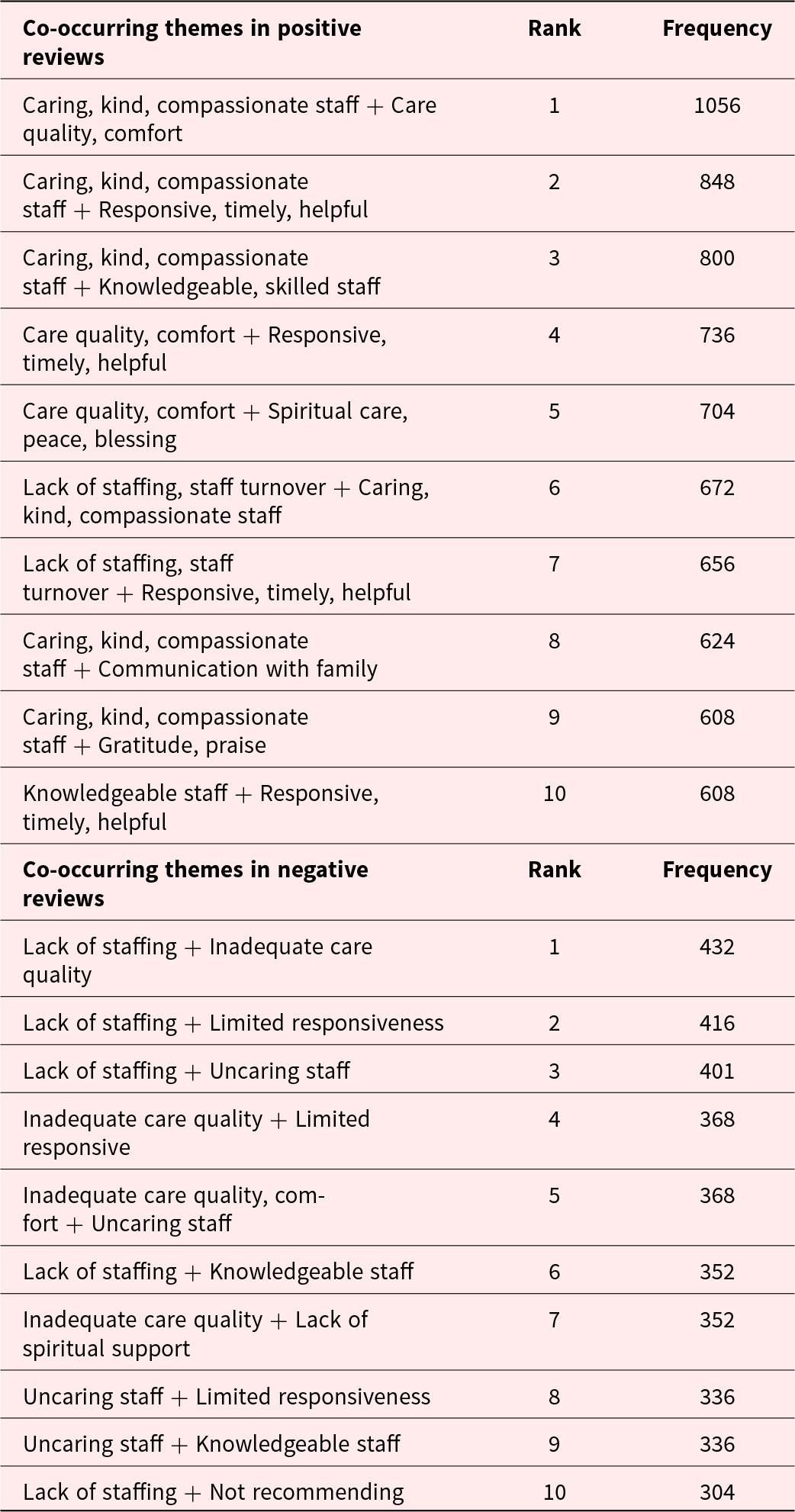

To test our model of overall hospice quality, we ran co-occurrence to analysis for the most common positive and negative themes. The results of the 10 most co-occurring themes are shown in Table 5. There was a significant negative correlation between the top 10 positive and top 10 negative themes (r = –.45, p < .001), indicating that reviews mentioning positive themes were less likely to mention negative themes, and vice versa. This provides evidence of an emerging model of hospice care quality from these themes. Figure 2 displays the final model of hospice quality developed from review themes, Watson’s carative factors, and CAHPS indicators.

Figure 2. Hospice Quality Model

Table 5. Co-occurrence analysis for most common themes (n = 3393)

Note: These themes represent the most common combinations of themes that occur in the reviews. The co-occurrence frequencies represent the number of times these themes are mentioned together in the reviews. For example, “Lack of staffing” and “Inadequate care quality” co-occur 432 times in the negative reviews. This provides evidence of an emerging model of hospice care quality from these themes.

Discussion

This study aimed to qualitatively code themes in hospice caregiver reviews, discover review themes, and develop a model of hospice quality. In this section, we first explore topics, prevalence and sentiment arising from the caregiver reviews, their alignment to CAHPS measures and Watson’s factors, and finally we comment on our methods.

Caring staff, care quality, and comfort

Watson’s caring theory proved beneficial in interpreting the needs of caregivers of the deceased and the co-occurrence findings substantiate the model that was developed. All 10 of Watson’s carative factors were reflected in the themes identified from the reviews (Figure 2). In the subsequent discussion, we exemplify areas where the review themes, CAHPS scores, and carative factors share conceptual congruence. The top 2 themes Caring staff and Care quality were represented by the first 2 carative factors, “(1) The forming of humanistic-altruistic value systems” and “(2) Installation of faith and hope.” Watson advised that care should be delivered from a place of love (Watson Reference Watson1988). Likewise, decedent caregivers agreed since they endorsed altruistic care and caring professionals most prominently of all themes. This finding is congruent with results from Yelp studies in hospitals (Ranard et al. Reference Ranard, Werner and Antanavicius2016; Raths Reference Raths2016), and nursing homes where caring and compassionate staff were frequently mentioned by reviewers (Johari et al. Reference Johari, Kellogg and Vazquez2018; Schapira et al. Reference Schapira, Shea and Duey2016). Our findings also agreed with the Yelp hospice study by Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Cardenas and Singleton2021) and the Yelp hospital study by Ranard et al. (Reference Ranard, Werner and Antanavicius2016). Rahman’s most prevalent themes were as follows: (1) compassionate, caring staff, identified in nearly half (46.28%); (2) gratitude and recommending (44.74%); (3) timeliness or responsiveness (39.63%); (4) communication (23.37%); and (5) quality of care (21.05%). Caring staff, gratitude, responsiveness, communication, and care quality were shared between the 3 studies as commonly mentioned themes.

On the topic of staffing, findings on the Lack of staffing highlight the reality that staff retention is a prevalent issue in the US hospice industry. It is incumbent on providers to strive for improved staff retention, as continuity of care is a critical aspect expressed by decedent caregivers. Also, governing agencies should be intervening to provide development, education and training incentives and opportunities for nurses and nursing aids for healthcare, in general, and end-of-life care specifically. Staffing is required for responsiveness and good communication.

Responsiveness and communication

The third most prevalent theme, responsiveness, aligned conceptually with the carative factor, “(9) Assistance with the gratification of human needs.” Given that many hospice patients are cared for in their homes, the importance of swift responses to care requests is quite understandable. The looming reality and inevitability of death heightened the need for prompt responsiveness. Reviewers expressed that they anticipated a high degree of responsiveness.

Good communication is at the core of the carative theme, “(4), Development of a helping-trust relationship.” Poor communication was more likely to be reported than good communication in this study. One explanation is that caregivers come to hospice expecting good listening and attentiveness. They likely report this as good care quality or caring staff since these aspects are likely perceived as hallmarks of good service. However, when communication falls short, the care process deteriorated, as seen in many negative reviews where poor communication is a primary grievance. In negative reviews, inadequate communication and lack of responsiveness emerged as the most frequent complaints.

Emotional, spiritual, bereavement support

Emotional, family support, and bereavement services were harmonious with the carative factor, “(5) The promotion and acceptance of the expression of positive and negative feelings.” Reviewers reported that emotional and bereavement support during and after hospice was vital to them. In the CAHPS survey, CMS assesses both aspects as well. One of the 8 CAHPS indicators of hospice quality is “emotional and spiritual support.” The theme of spiritual care, peace, and blessing appeared in one-fifth of all reviews. Spiritual care harmonized with the carative factor, “(10) The allowance for existential-phenomenological, spiritual forces.” Hospices should always bear in mind the importance of providing care to the entire family, particularly considering that the primary caregiver will represent the patient and their loved ones when offering feedback about hospice care during the CAHPS process.

Recommending, gratitude, and management

In our understanding, endorsements and expressions of gratitude from caregivers typically represent a positive response to excellent care, just as criticisms about management often signal inadequate service. Signs of gratitude suggest the establishment of a therapeutic bond. Caring behaviors and good communication were associated with the outcome of caregiver satisfaction as expressed in grateful language in review narratives. It is likely that caregivers who make an effort to write reviews and express thanks to the hospice team feel a sense of connection to the compassionate professionals who built relationships with them. The high incidence of negative reviews is concerning, suggesting that certain hospices may not be providing effective care to a significant number of their admitted patients.

Interdisciplinary and comprehensive care

The interdisciplinary and comprehensive theme showed up in comments about all-inclusive and holistic care. Pain and symptom management, also a critical CAHPS measure, is the central goal of palliative care that aligns well with Watson’s carative factor “(8) The provision of the supportive, protective, and (or) corrective mental, physical, societal, and spiritual environment.” Education or training, a CAHPS measure with 6 survey questions, aligns with Watson’s factor, “(7) The promotion of transpersonal teaching-learning.”

Implications for hospice quality evaluation

To encapsulate, both close-ended CAHPS scores and open-ended online reviews offer significant conceptual similarities and offer supplementary insights. Particularly in the case of hospices with sparse CAHPS results, it is crucial to employ various quality evaluations to comprehend the full scope of hospice care quality. While close-ended surveys supply standardized, quantifiable data, open-ended reviews offer added dimensions of depth, context, and individual viewpoints. Through the amalgamation of these different types of evaluations, hospices can achieve a more comprehensive understanding of caregiver experiences, which allows them to pinpoint strengths, areas needing enhancement, and potential areas for service improvement. This eventually leads to an overall enhancement in the quality of care provided to patients and their families.

These findings suggest that hospices should consider actively engaging with and responding to their reviews. This not only demonstrates that the hospice staff genuinely cares but also helps to validate the experiences of patients, be they positive or negative, potentially triggering enhancements in service delivery. Another inference drawn from these results is that since caregivers frequently mentioned caring staff and overall quality in their reviews, it would be beneficial for CMS to integrate at least one question for each aspect into their 47-question survey. For example, “Do you feel the hospice staff cared about you and your loved one?” Hospice care services are intimately linked to, and evaluated in light of, the caring, or uncaring, people providing the services.

Watson’s caring theory serves as a valuable framework for understanding, and all the carative elements found expression in the themes we discovered and developed. The reviews emphasize the significance of the human-centric and holistic aspects of hospice care – compassionate caregivers, quality of care, and emotional, spiritual, and bereavement support (Barry et al. Reference Barry, Carlson and Thompson2012). In contrast, CAHPS scores are oriented to government-evaluated service measures (CMS 2021). There was construct agreement between the 8 CAHPS score indicators, 8 review themes, and Watson’s caring theory. Reviewers appeared to endorse caring people, availability, and timely caring experiences as top of mind when they reviewed the hospice. Recommending is the highest compliment a hospice can receive.

Strengths, limitations, and future research

This study had certain significant strengths and limitations. Among the key strengths were the utilization of both human and machine coding methods with considerable sample sizes, enabling us to determine 10 central themes. By confining our research to the 50 largest providers, we ensured a sufficient number of reviews per hospice, thereby preserving the study’s validity, though this meant excluding some smaller providers. However, as Google and Yelp reviewers are not randomly selected but volunteer contributors, the sample in this study may display a bias toward the demographics of those who post reviews.

On our methodological process, for anyone seeking to conduct this type of sentiment analysis, we strongly recommend also reading in the star ratings of the reviews as the narrative review portion is processed. This allowed us to narrow negative topics to negative reviews to increase the accuracy of sentiment analysis, and reduce false negatives. Such that, negatively oriented themes, for example “Family support, less than expect” do not trigger in any positive sentiments.

TextBlob is an alternative to Google NLP that does not require setting up a Google NLP API account. However, we found that it is not as effective at detecting sentiment direction. Both Google NLP and TextBlob produced nearly the same prevalence results, within ± 3%. In this study, we normalized our magnitude scores to range from 0 to 1, which made analysis more straightforward, since other variables matched. However, we noticed that using the raw scores (allowing them to range from 0 to infinity) offered a better comparison of emotional intensity and review length, we plan to use that method in future studies.

The sentiment analysis carried out in this study presents certain advantages and drawbacks. The application of NLP techniques allows for the handling of vast volumes of unstructured text data, offering valuable insights into the sentiments expressed in the hospice caregiver reviews (Liu Reference Liu2012). The sentiment analysis approach employed in this study is based on machine learning algorithms and lexicon-based methods, which have been widely used in sentiment analysis research (Pang and Lee Reference Pang and Lee2008).

Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize several limitations. First, the quality and representativeness of these reviews could differ, and potential biases in the amassed data might be present (Cambria and Hussain Reference Cambria, Hussain, Hussain, Chang and Meethan2012). Second, sentiment analysis techniques may not capture the full complexity of human sentiment and emotions. While efforts have been made to develop accurate sentiment analysis models, the interpretation of sentiment can still be subjective (Cambria and Hussain Reference Cambria, Hussain, Hussain, Chang and Meethan2012; Nasukawa and Yi Reference Nasukawa and Yi2003). The sentiment scores and magnitude assigned to the review themes are based on algorithms and predefined lexicons, which may not fully capture the nuances of the caregivers’ experiences and emotions (Liu Reference Liu2015).

In this study, over 95% of the reviews received were either 1-star or 5-star reviews, indicating caregivers perceived their experiences as either excellent or terrible. This fact was utilized as an advantage in this study, as the distinct themes of negative criticisms and postive praises could offer insights into the user experience at both extremes of high and low hospice performance. As our central interest lay in sentiments derived from the narrative section of the reviews, potential floor and ceiling effects from bimodal data, that could influence the outcomes, are not considered significant. In this context, the star ratings of the reviews were only presented as descriptive data and were not included in the analysis.

The caregiver perspective is vitally important, but enrollees often expect more than is in-scope with the Medicare benefit. A final limitation was that we were not able to assess where caregiver’s expectations were out of scope; however, in a parallel study published using the same dataset, we assessed that about 1 in 6 review expressed expectations outside the scope of the hospice Medicare benefit (Hotchkiss Reference Hotchkiss2023). Thus, for a well-rounded understanding of the quality of hospice care, it is crucial to embrace diverse viewpoints and include feedback from various stakeholders (Cambria and Hussain Reference Cambria, Hussain, Hussain, Chang and Meethan2012). Another hospice quality study linked employee satisfaction to caregiver satisfaction (CAHPS) scores (Hotchkiss Reference Hotchkiss2022).

When considering factors about the researchers that could impact the study, such as personal attributes, experiences, and preconceived ideas, it should be noted that the primary researcher is an experienced hospice professional who has observed the highest and lowest levels of hospice quality. If there exists any bias, it could potentially lean toward unearthing deficits in hospice quality and urging hospices to elevate their standards. Further research on hospice quality should investigate caregiver expectations and draw comparisons between review themes based on their profit status.

Conclusions

Hospice caregivers were most likely to recommend hospices with caring staff, providing quality care, being responsive to requests, and offering family support, including bereavement and supportive care. Close-ended CAHPS scores and open-ended online reviews have substantial conceptual agreement. Open-ended reviews place more value on the human and big-picture elements in hospice – caring people and overall care quality. All 10 of Watson’s carative factors and all 8 CAHPS measures were presented in the discovered review themes.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the work of Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Cardenas and Singleton2021 on review themes and categories which, were a helpful framework in the human theme coding stage of our analysis. Also, we wish to thank Brereton et al., Reference Brereton, Matlock and Fitzgerald2020 for their theme exploration and discerning caregiver expectations which we used in our parallel study on overall US hospice quality (Hotchkiss et al., Reference Hotchkiss2023).

Competing interests

None.