Discretion is at the core of executive power. This discretion, which gives chief executives the freedom to decide how to implement policy initiatives, shapes policy from the construction of border walls and the preservation of rainforests to trade barriers and public health measures that combat global pandemics. Consequently, political observers frequently speculate about discretion in the shadow of pending actions, and calls to either rein in or expand presidents' discretion are as old as the foundings of most political systems – and continue today.Footnote 1

Yet important theoretical questions about presidential discretion remain untested because of measurement challenges. Conventional views of presidentialism suggest that the superior information available to the president, combined with the president's ability to act quickly in a crisis, lead to variation in discretion across policy areas (for example, Epstein and O'Halloran Reference Epstein and O'Halloran1999; Volden Reference Volden2002). Presidents leverage this discretion to act alone, often signing executive decrees or orders (for example, Carey and Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1998; Howell Reference Howell2003; Negretto Reference Negretto2004; Opalo Reference Opalo2019). To answer more basic questions about how much (or how little) discretion the president has, journalists often report on expert opinions regarding presidential discretion – but these reports are limited to particular policies and are not systematic.Footnote 2 The few efforts to measure this concept in the social sciences rely on divergent understandings of the source of authority, do not scale across policy areas, or are not specific to the authority of the chief executive.

We calculate and present estimates of presidential discretion over public policy in the United States derived from a survey of a panel of experts in the social sciences, humanities and law. More specifically, we utilize a pairwise comparison approach to calculate latent discretion across policy areas on a common scale. Sources of presidential discretion are varied: presidents may be enabled by ambiguous statutes, unexpended appropriations, the actions of presidential appointees in executive agencies or constitutions. Expert judgments implicitly account for this variation. In contrast to other approaches to measuring discretion, this pairwise comparison framework also allows us to provide estimates of uncertainty.Footnote 3 Our approach reduces informational demands by asking respondents to compare pairs of policy areas, which improves the precision of the estimates relative to other expert surveys. Moreover, it can be applied broadly to political contexts outside the United States.

After we obtained estimates from this survey, we validated them by examining their ability to organize key theoretical propositions. We find that presidents have more discretion in foreign – relative to domestic – policy (sometimes referred to as the ‘two presidencies’ thesis; see Canes-Wrone, Howell and Lewis Reference Canes-Wrone, Howell and Lewis2008; Wildavsky Reference Wildavsky1966), and that greater discretion is associated with more unilateral presidential initiatives in the contemporary era. These results are robust to numerous alternative measurement strategies and multiple measures of presidential policy outputs. This new measure has broader implications for the study of executive power. Research on political institutions has argued that the delegation of policy-making authority promotes its use. We find evidence that the president's discretion is associated with the issuance of unilateral decrees. Moreover, we argue that our approach can be adapted to study presidential discretion in a comparative context, and to examine the gap between public and expert perceptions of presidential power.

Presidential Discretion and Policy Change

Discretion in a political setting is the authority to decide whether or not to take policy action, and if so, which action or policy to choose. A variety of policy makers enjoy this kind of discretion, including presidents, federal bureaucrats, teachers, police officers, judges and state governors. Though presidents are typically chief executives whose exercise of discretion has broad influence on policies and other political actors, presidential discretion has mostly escaped systematic empirical investigation.

Presidents derive their discretion from a variety of sources, including explicit grants of authority or useful ambiguities in constitutions, and most importantly, delegation from legislatures. The literature on delegation is vast and spans disciplines, but the stylized process is easy to summarize.Footnote 4 Laws often do not (or cannot) spell out exactly how policy should be carried out. Legislators sometimes lack the necessary time or expertise (for example, Landis Reference Landis1938). They may prefer generalities to avoid making controversial decisions (Fox and Jordan Reference Fox and Jordan2011) or because they lack the expertise to develop higher-quality policy. As a result, laws invariably include some imprecision that allows (or even asks) the executive branch to step in (VanSickle-Ward Reference VanSickle-Ward2014). This process is ubiquitous. According to one recent estimate, more than 99 per cent of all major US laws contain at least some delegation to government agencies (Clouser McCann and Shipan Reference Clouser McCann and ShipanForthcoming). Problems and controversies arising from this basic fact motivate much research in the legal subfield of administrative law.

Theories of delegation often focus on determinants of the amount of authority that is delegated. Numerous studies argue that when a legislature delegates, it also decides how much discretion for developing new policies should be attached to that grant of delegation (for example, Epstein and O'Halloran Reference Epstein and O'Halloran1999; Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002; Stephenson Reference Stephenson2006). Presidents can also draw on other existing laws as a basis for policy-making authority, even if these laws do not specifically ask the president to take action. The amount of discretion varies across policy areas because Congress might constrain the president in one area but allow for greater discretion in another, or because the president recognizes other sorts of constraints (for example, via courts, resource limitations or personnel) on the use of discretion. Theories typically predict greater discretion when the president and Congress are aligned (known as the ‘ally principle’), and when Congress is more uncertain about the correct policy.

This dynamic contributes, for example, to a conventional proposition in presidency scholarship – known as the ‘two presidencies’ thesis. Wildavsky (Reference Wildavsky1966) first remarked that presidents tend to have ‘much greater success’ in foreign than in domestic affairs (162). Evaluations of this notion over the next 40 years were decidedly mixed; most research finds a time-bound effect (for example, Cohen Reference Cohen1982; Fleisher and Bond Reference Fleisher and Bond2000). Most importantly, the logic of the president's comparative boost in influence remained mostly unstated until Canes-Wrone, Howell and Lewis (Reference Canes-Wrone, Howell and Lewis2008). The critical components of this logic are themselves reasons for delegation: presidents can act quickly in foreign affairs, are better informed and have incentives to care about international affairs (Howell, Jackman and Rogowski Reference Howell, Jackman and Rogowski2013). Foreign affairs tend to exacerbate the information asymmetry between the president and Congress, and the greater this asymmetry, the more discretion legislators are likely to grant.Footnote 5 Each of these reasons contributes to a straightforward proposition: presidents should have greater discretion in foreign affairs.

Contemporary scholarship also sheds light on how this discretion will be used once it is granted. Theories of unilateral action are critical for understanding presidents’ policy making. Their basic intuition has been articulated by presidents, candidates and voters. Presidents are seen as first movers who can change the status quo, especially when legislatures are gridlocked (Carey and Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1998; Negretto Reference Negretto2004; Opalo Reference Opalo2019). In the US context, formal theories of unilateral action incorporate several key elements of this stylized narrative, with the president modeled as a first mover and Congress's ability to respond limited by super-majoritarian requirements (for example, Chiou and Rothenberg Reference Chiou and Rothenberg2014; Howell Reference Howell2003). Most of this theoretical work focuses on comparative statics associated with changes in Congress and the president's preferences. This focus is partly a function of the relative ease of measuring ideological disagreement or divided government. Thus several decades of research on unilateral action have established empirical associations between the issuance of various presidential directives and political covariates like the size of the majority party, the ideological distance between the president and Congress, polarization and divided government.Footnote 6

But assumptions about presidential discretion are critical to understanding unilateral action. In Howell (Reference Howell2003), a discretion region enforced by the Supreme Court explicitly limits the policy gain associated with unilateral action. More recently, Chiou and Rothenberg (Reference Chiou and Rothenberg2017) demonstrate that limits on the direction and degree of presidents' proposal power play a critical role in predicting outcomes. Because discretion is typically modeled as an exogenous parameter that determines the set of alternative policies available to a president, more discretion implies more opportunities for unilateral action.Footnote 7

Measuring Discretion

Given the importance of discretion to understanding policy making across separate powers, how have scholars measured it? An initial answer is: they often do not. Sometimes they focus on substituting delegation at the federal level for delegation to the states (Clouser McCann Reference Clouser McCann2016). At other times they turn their attention to other covariates of delegation, such as the spatial distance between policy makers (for example, Shipan Reference Shipan2004). Relatedly, in studies of unilateral presidential policy making, scholars usually ignore the comparative static predictions related to discretion parameters.

Attempts to measure discretion have typically focused on the discretion afforded to and exercised by government agencies. Although we are interested in presidential discretion, which is conceptually and empirically distinct from agency discretion, the approaches of studies that measure agency discretion are informative. Epstein and O'Halloran (Reference Epstein and O'Halloran1999) conceive of discretion as the amount of delegation that a law provides minus the extent of constraints on that delegation. This first systematic measure of discretion enabled empirical tests of theories of delegation and highlighted the importance of procedural constraints (Franchino Reference Franchino2004). Most recently, Anastasopoulos and Bertelli (Reference Anastasopoulos and Bertelli2020) extended this approach by leveraging supervised machine learning.

Alternatively, Huber and Shipan (Reference Huber and Shipan2002) argue that the length of a law can serve as a useful proxy for the amount of discretion. This approach provides a measure more straightforward to compute, and has been used by a number of other studies (for example, Clinton et al. Reference Clinton2012; Randazzo, Waterman and Fine Reference Randazzo, Waterman and Fine2006; Randazzo, Waterman and Fix Reference Randazzo, Waterman and Fix2011). Most recently, Bolton and Thrower (Reference Bolton and Thrower2019) develop an approach to measuring discretion that relies on information that can be gleaned from appropriations bills. They conceive of discretion as the ratio of new budget authority to the number of pages of limitation riders (for example, MacDonald Reference MacDonald2010).

Existing approaches, however, have important limitations. The process of hand coding legislation is difficult to replicate. Hand coding third-party summaries of legislation relies on the assumption that the descriptions of delegation contained in the summaries are written in a consistent fashion over time. In the case of the CQ Almanacs, this consistency is unlikely because the yearly summaries have become shorter over time, in concert with a secular trend in Congress towards long, omnibus legislation. Moreover, though Anastasopoulos and Bertelli (Reference Anastasopoulos and Bertelli2020) offer a scalable and replicable extension of this approach, it still relies on the initial hand coding of third-party summaries. Word counts are valuable for comparisons within a policy area, but are potentially problematic to use across policy areas. This approach also precludes the inclusion of omnibus legislation that spans multiple policy areas. Although Bolton and Thrower rightly recognize that appropriations can constrain agencies, ignoring the role of authorizing statutes seems likely to introduce bias. It is not clear why appropriations alone capture delegation, independent of the underlying authorizations that can themselves constrain or increase discretion.

Most importantly, none of the measures described above was intended to capture the discretion of a chief executive. In fact, some conflate procedural constraints on agencies with presidential discretion. Limitations riders and oversight provisions can privilege presidential influence over agency policy making. Yet using existing measures, including these provisions would decrease estimates of discretion. This is an important omission in the US context, since executive policy making appears to be increasingly driven by the initiative of the elected head of the executive branch.

In summary, our goal is to provide estimates of presidential discretion in the United States, which we distinguish from the discretion afforded to executive branch agencies. Presidents can, of course, instruct uninsulated agencies to take policy actions or suggest these actions to them; hence, agency discretion might comprise one component of presidential discretion. However, presidents also have the authority to exercise discretion in a variety of other ways – for example, when Congress explicitly gives the president discretion, when ambiguous statutes allow presidents to claim authority and discretion, when the courts issue rulings that broaden the president's ability to act and when the Constitution provides for discretion. Thus presidential discretion is broader than and conceptually distinct from agency discretion.Footnote 8

Measuring Presidential Discretion With Experts

As the diversity of measures already discussed suggests, prior scholarly work generally conceives of discretion as a combination of legal authority, resources and constraints. Due to the challenges associated with accurately capturing each of these aspects of discretion, it is especially difficult to develop a measure that is comparable across policy areas. Some areas of public policy, for example, might rely on a free hand written into law or an implicit deference granted by the American Constitution. Others might be based on the raw number of available personnel and funds to determine the ultimate discretion available to a president.

Expert ratings are particularly suited to capturing concepts that, like executive discretion, are latent and thus inherently difficult to measure with observable data. Not surprisingly, political scientists have increasingly turned to expert surveys to measure a range of latent political concepts, such as the ideology of government agencies (Clinton and Lewis Reference Clinton and Lewis2008), judicial independence (Feld and Voigt Reference Feld and Voigt2003), the positions of political parties (Laver Reference Laver1998; Ray Reference Ray1999), legislative power (Chernykh, Doyle and Power Reference Chernykh, Doyle and Power2017; Fish and Kroenig Reference Fish and Kroenig2009) and democracy itself (Treier and Jackman Reference Treier and Jackman2008). Most involve variants of item response models, which leverage multiple raters who are each given a list of items to place on a scale. For example, Clinton and Lewis (Reference Clinton and Lewis2008) asked a set of experts to rate government agencies on a scale containing three options: slant liberal, slant conservative and neither (with a fourth option of ‘I don't know’ also available). Other studies have asked experts to place items on a Likert scale.

We instead ask experts to make a series of paired comparisons. Though this approach is almost 100 years old and has been widely applied across the social sciences (Bradley and Terry Reference Bradley and Terry1954; Carson and Czajkowski Reference Carson and Czajkowski2014; Louviere, Flynn and Carson Reference Louviere, Flynn and Carson2010; Thurstone Reference Thurstone1927), it has only recently been applied in political science as a means of efficiently coding texts (for example, Benoit, Munger and Spirling Reference Benoit, Munger and Spirling2019; Carlson and Montgomery Reference Carlson and Montgomery2017). As Carlson and Montgomery note, paired comparisons simplify coders' tasks by replacing the rating of each item along a latent scale with a series of binary, discrete choices. In our context, this involves a simple judgment: given two policy areas, in which does the president have more discretion? This approach improves the quality of the resulting measures by reducing the cognitive burden on raters.

Our process involves five steps, which we elaborate in the following sections:

(1) Define a set of public policy areas.

(2) Identify a set of subject matter experts.

(3) Define discretion.

(4) Present each expert with twenty pairs of randomly selected policies, and ask the expert to select the policy area in each pair over which the president has more discretion.

(5) Estimate a random utility model to recover the latent level of discretion in each policy area, relative to others.

This approach has a variety of appealing features that address some of the limitations of past measures of discretion. It provides estimates of uncertainty. It spans a cross section of the policy-making landscape in the United States and beyond. It is not sensitive to individual hand coders, or arbitrary changes in secondary sources. It identifies the specific actor thought to enjoy discretion – the president, whose discretion is overlooked in past work on the topic. Finally, by leveraging expert opinions, our approach implicitly incorporates numerous sources of discretion (such as statutory language, appropriations, the Constitution). On their own, any of these would provide an incomplete description of the concept.

Topic Selection

To begin our task of measuring the degree of presidential discretion, we first need to identify the relevant set of policy areas. To do so, we turned to the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP), which categorizes the vast domain of public policy into twenty-one broad areas, such as Civil Rights, Health, Defense and Foreign Trade, and then further subdivides each of those broader categories into a series of more specific subtopics.Footnote 9 The category of Health, for example, is disaggregated into subcategories that include Health Insurance Availability and Costs, Prescription Drug Coverage and Costs, Abortion Policy, and Substance Abuse Prevent and Treatment. We selected the policy topics from each category in which the president is involved in implementing or setting policy. One advantage of utilizing this rating scheme is that the resulting measures of presidential discretion are easily merged with numerous other political event and text datasets. This makes it relatively straightforward to extend our approach to presidents beyond the United States.

We selected fifty-four separate topics for inclusion in our survey. For each major topic, we determined whether limiting a policy area to a single major topic would obscure heterogeneity in policy-making authority. Agricultural policy making, for example, includes diverse and separate functions such as direct payments to farmers and ranchers, export promotion and food inspection, so we identified and included these subtopics, rather than just the broader major topic. We generally used the same labels for a policy area as the CAP, but in a few cases we changed or simplified the labels to make the subject of the policy area clearer. A complete list of the topics and label changes appears in Appendix Table A1.

Expert Selection

We sought experts with specialized knowledge of policy making by American presidents and the executive branch. Here, we drew upon several sources. First, we turned to the Presidents and Executive Politics section of the American Political Science Association. From this section we identified experts by looking at lists of section officers, award committees and award winners. We then turned to journals, beginning with Presidential Studies Quarterly and then examining more general journals, to identify scholars who had written on these topics. Next, we supplemented these two approaches by sending out inquiries to scholars who publish on these topics, asking them for suggestions of other scholars with expertise on presidential policy making. Because we wanted to reach beyond political science to the disciplines of law, economics, history and public policy, we especially used this approach to identify scholars in those fields. Ultimately, we identified thirty-three of these scholars by referral.

Our final panel included 173 scholars. Of the experts we contacted, 128 completed the survey, representing a response rate of 74 per cent, which is in line with those of other expert surveys. Clinton and Lewis (Reference Clinton and Lewis2008), the closest in subject matter to our study, report a response rate of 70 per cent. As we show below, because of the relative agreement of raters and the number of comparisons each rater completed, this sample is more than sufficient to recover precise discretion estimates. The majority of these respondents – seventy-nine of them – come from the discipline of political science. But we also had respondents from the fields of law (thirty-five), economics (six), history (ten) and public policy (six).Footnote 10 To gauge the relative robustness of these measures, we also report findings for scores that exclude political scientists (see Appendix Figures B7 and B8). We defer discussion of these alternative scores until the presentation of the results.

Definition of Discretion

The survey presented experts with the following prompt:

Presidents can use their legal authority as the head of the executive branch to change policy without Congress. In some cases, they have a great deal of discretion, or freedom, to change existing policies and create new ones. In others, their ability to use executive actions to change or create policy is more limited.

The implied definition of discretion has several critical components, which are designed to prime a distinct concept without constraining the considerations that raters bring to their choices. First, it defines discretion as the freedom to change policy that results from the president operating as the head of the executive branch. Secondly, it explicitly mentions actions that are independent of Congress, which is central to how scholars and the public think about executive unilateralism. Moreover, as we show in the Appendix, priming ‘without Congress’ is important for excluding non-executive-driven policy change.

Finally, one additional concern is the temporal relevance of the resulting measure. A score that did not limit the time period in question would face two issues. First and most obviously, many of the topics we present did not exist during the administrations of John Quincy Adams or Grover Cleveland. Secondly, the choices of contemporary experts will likely be subject to some degree of recency bias, implicitly rendering these scores relevant to only the contemporary era. For these reasons, we explicitly prompt experts with the previous four presidents: Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump.Footnote 11 Overall, then, our measure is time invariant. Although this means we cannot use it to assess changes in presidential discretion over time, or to measure presidential discretion in earlier eras, these limitations are outweighed by the benefits of being able to measure discretion over policies that have been important in recent years and to avoid confounding assessments of discretion with evaluations of specific presidents.

Implementation

Each respondent was asked to compare twenty pairs of randomly selected terms. We presented each respondent with two policy areas – for example, National Parks and Monuments versus Media and Broadcast Industry Regulation – and asked them to identify the item in each pair over which the president has more discretion. Policy areas were sampled with replacement across (but not within) pairs. It was not possible for a comparison to present the same policy area in one pair, but policy areas could appear more than once across the set of twenty pairs. Appendix Figure A1 presents a sample screenshot.

The expert survey was fielded through email invitations sent by the authors beginning on 27 March 2019. Follow-up email reminders were sent two weeks later to those who had not yet responded. Responses were received between 28 March and 28 May, with the vast majority arriving within a week of our request. Some scholars responded by choosing not to participate, and several others did not complete the survey. Appendix Table A3 shows some minor differences across invited and completed surveys by gender and seniority, but these are not statistically distinguishable by conventional standards. Overall, these figures – in addition to the high response rate – demonstrate that this expert panel is broadly representative of the subject field.

Estimation

We estimate a random utility model to obtain discretion scores. Following Carlson and Montgomery (Reference Carlson and Montgomery2017), we model the probability of a paired selection with parameters for our latent measure and respondent quality. Specifically, the probability that topic j is selected over topic i is a function of the discretion of each topic (d j, d i), weighted by the quality of rater k, q k, such that:

In this framework, respondent quality can be thought of as the degree to which a respondent agrees with other respondents. We estimate these models in RStan with diffuse priors (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter2017). These baseline estimates treat all respondents the same, incorporating no background or demographic characteristics.

There are, of course, numerous potential alternatives to this model. One is to exclude respondent quality parameters so the model above is equivalent to a standard Bradley-Terry model (Bradley and Terry Reference Bradley and Terry1954). Another is to include exogenous regressors to predict respondent quality. We forgo the latter for now because investigating hypotheses regarding respondent quality are not necessary to address our research question. These data might be useful, for example, for investigating partisan determinants of responses, but these are not central to understanding latent presidential power. However, it is clear that all raters are not equally qualified to answer such questions. As we report in Appendix Section A3, there is variation in the incidence of transitivity violations across experts. All parametric, probabilistic choice models assume some form of stochastic transitivity, which itself is not empirically verifiable. But some raters are more internally inconsistent than others. This implies that some effort to model respondent quality – whatever its determinants – is necessary.Footnote 12 This suggests that the quality parameters, q k, are appropriate. As another alternative, we also examine simple, non-parametric scores that represent the probability that a topic will be selected. In general, given the straightforward structure of the task, we have found that the rank order of discretion by topic does not significantly change across estimation strategies. We report the results for these supplementary estimates in the Appendix.

Presidential Discretion

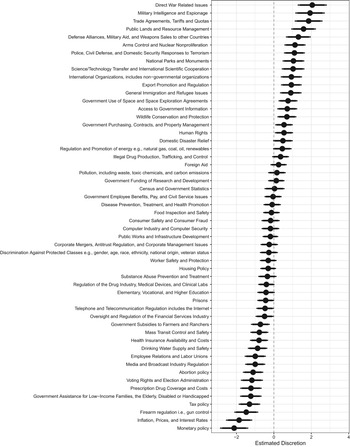

The baseline estimates of presidential discretion, reported in Figure 1, exhibit strong face validity. Experts identify issues like immigration, trade, intelligence and defense as highly discretionary. Presidents' constitutional prerogative in war-making is believed to grant them considerable discretion, and Congress has largely delegated unilateral authority to revise tariff schedules to presidents. In contrast, issues like abortion, gun control and monetary policy appear in the lowest quartile. Abortion and gun control are largely matters of state control, and subject to prevailing legal precedents that limit the opportunity for intervention.

Figure 1. Expert estimates of presidential discretion

Note: sample includes 128 US scholars in political science, history, economics and law.

Furthermore, initial diagnostic checks suggest that the scores and procedure perform well. Notably, these scores are not driven by whether agencies have substantial discretion over a policy area. We examined this possibility in two ways, which we describe in more detail in Appendix Section B2. First, we compared our measure of presidential discretion to existing measures of agency discretion. As the figures and discussion in the Appendix show, we find that our measure of presidential discretion is orthogonal to both a statute-based measure and an appropriations-based measure.

Secondly, we consider policies that fall under the purview of independent agencies. By virtue of their location outside the executive branch, these agencies are formally independent of both Congress and the president, and can thus be assumed to have some degree of discretion over policy areas within their jurisdictions. Although there are some policy areas in which the president is perceived to exercise a high level of discretion over policies that are covered by independent agencies – such as Government Purchasing, which is handled by the independent General Services Administration, and Export Promotion and Regulation, where the Export-Import Bank plays a significant role – there are many other areas in which independent agencies exercise substantial discretion but our experts code presidents as having limited discretion. Table B8 reports a complete listing of policy areas and independent agencies’ jurisdictions. Given the lack of a relationship between the policy areas that fall under the jurisdiction of independent agencies, other ratings of agency discretion, and our ratings of presidential discretion, we are confident that our measures are not simply capturing agency discretion.

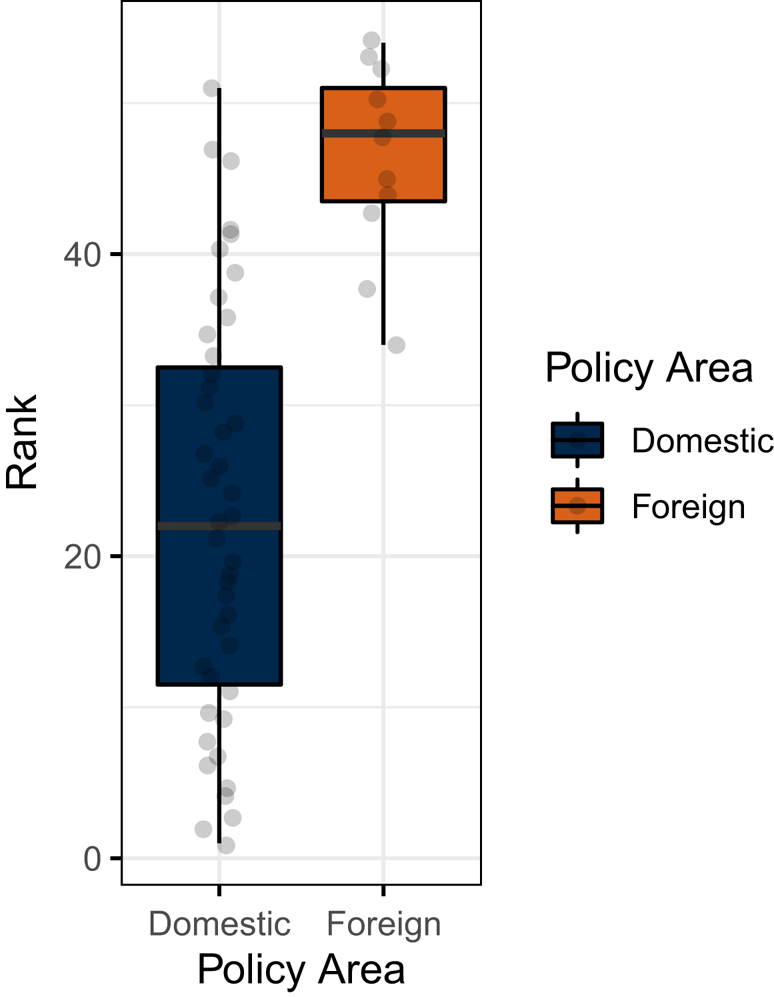

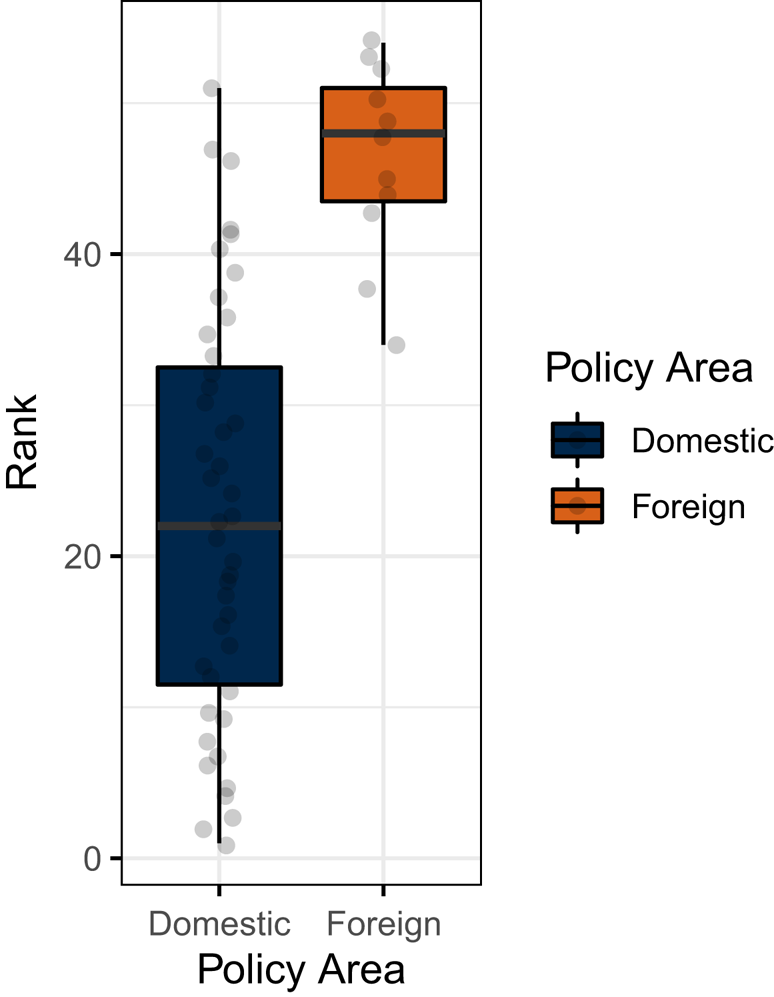

Of course, these estimates are useful for more than just basic descriptions of stylized accounts of policy areas. One way to validate them is to examine the central propositions posed by theories of delegation and unilateral action. Consistent with theories of delegation, the estimates largely confirm the ‘two presidencies’ dynamic. As Figure 2 indicates, policy areas reasonably classified under the umbrella of foreign affairs tend to be ranked higher in presidential discretion (that is, as ones over which presidents have more discretion). In Figure 2, we have rank ordered the policy areas to reduce the likelihood that the differences are being driven by outliers like war and military intelligence, but the results remain unchanged across latent trait estimation strategy or when using the continuous scores.

Figure 2. The two presidencies thesis

Note: higher rank indicates more discretion. Arms control, defense alliances, war, exports, foreign aid, refugees and immigration, human rights, international organizations, military intelligence, responses to terrorism and trade agreements were classified as foreign policy areas. Points jittered to prevent over plotting.

While evaluating the two presidencies thesis is relatively straightforward, measuring unilateral action on the part of presidents is uniquely difficult among American political institutions. Unlike legislation, regulations or judicial decisions, the numerous formal and informal initiatives generated by presidents are not subject to any standardized record-keeping scheme. There are at least two dozen classes of documents that bear the president's signature and are the administrative means of unilateral action (Relyea Reference Relyea2005). Worse still, some notable actions – like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or No Child Left Behind waivers – appear to be classic examples of presidential initiatives, but cannot be traced to a formal presidential directive. Moreover, collecting and aggregating these myriad sources of potential action raises the issue of including orders that are insignificant or do not fit the standard spatial model of policy change (Chiou and Rothenberg Reference Chiou and Rothenberg2014; Howell Reference Howell2005; Mayer and Price Reference Mayer and Price2002). For this reason, we leverage multiple measures to assess the connection between discretion and unilateral action.

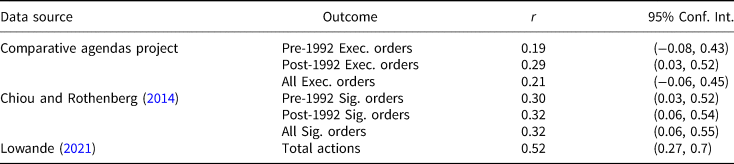

We first use raw counts of executive orders maintained by the CAP. To address the question of significance, we next utilize scores estimated by Chiou and Rothenberg (Reference Chiou and Rothenberg2014), who aggregate the ratings of retrospective and contemporary sources with a hierarchical item-response model. We subset the CAP executive order list to the set with a significance score greater than 0.5, which includes slightly more than the top quartile of orders. Finally, to address the potential omission of non-executive order initiatives, we use estimates of total unilateral action from Lowande (Reference Lowande2021). These totals include all directives published in the Compilation of Presidential Documents from 1992 through 2018, along with unclassified national security directives, and presidentially driven regulatory or enforcement initiatives mentioned in law reviews.

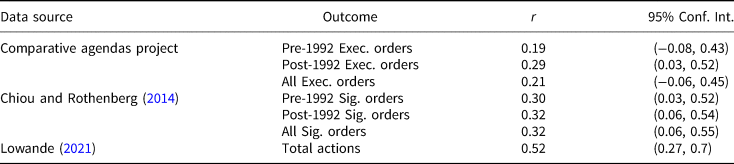

Overall, we find that discretion is positively associated with these measures of unilateral action. We report this series of correlations and bivariate relationships in Table 1 and Figure 3. The typical magnitude of this effect is around two additional significant orders during the 1992–2018 period for a one-standard-deviation increase in discretion.Footnote 13 This relationship is robust to non-parametric specifications of discretion (that is, rank transformation and mean selection scores), as well as analyses that take into account the uncertainty of the discretion scores by inverse error weighting.

Table 1. Discretion is positively associated with presidential action

Note: includes random utility model estimates of discretion. Executive order counts come from the Comparative Agendas Project; executive order counts from Chiou and Rothenberg (Reference Chiou and Rothenberg2014) were generated by setting a significance threshold of 0.5; estimates of total unilateral action come from Lowande (Reference Lowande2021), and include all directives, as well as non-directive actions like regulations and informal orders.

Figure 3. Presidential discretion and unilateral action by policy area, 1992–2018

Note: executive order counts (left plot) come from the Comparative Agendas Project; executive order counts (center plot) from Chiou and Rothenberg (Reference Chiou and Rothenberg2014) were generated by setting a significance threshold of 0.5; estimates of total unilateral action (right panel) come from Lowande (Reference Lowande2021), and include all directives, as well as non-directive actions like regulations and informal orders. Includes random utility model (RUM) estimates of discretion.

This relationship is also robust to different measures of unilateral action. The relationship is stronger as insignificant orders are removed and other types of directives beyond executive orders are included.Footnote 14 All revisions to trade barriers occur via proclamation (included in this measure), which improves its relative fit with the discretion scores. It is also reassuring that the relationship between unilateral action and discretion weakens prior to 1992, which suggests that the time horizon provided to experts as part of the definition of discretion was informative.

Another potential concern is that key predictions of the presidency theory we have assessed will be known to the expert raters. As a result, it might not be surprising that political scientists’ assessments ultimately reproduce conventional wisdom in the field. To investigate this concern, we re-estimated our scores using only non-political scientists. This subset of mostly legal scholars produced very similar assessments of the presidential discretion. As we show in the Appendix, these estimates also reproduce the patterns found in Figures 2 (B7) and 3 (B8). This gives us more confidence that these patterns are not a function of the predominance of the hypotheses themselves in the discipline of political science.Footnote 15 In summary, our new measure of presidential discretion comports with stylized accounts of the concept and usefully organizes observed cases of unilateral action over the previous four presidencies.

Discussion

Policy making in modern democracies cannot be understood without considering the discretion of chief executives. In American politics, the stakes of this discretion are high. Whether over 700,000 immigrants maintain their temporary legal status, whether utilities must use carbon-capture technology or whether Chinese imports slow to a trickle all feasibly depend on the whims of the president. Though contemporaneous reporting speculates about the legality of presidential moves, scholars have long known that the discretion to act is not random. By providing novel estimates of presidential discretion, our study demonstrates that this strategic process has produced a policy arena with variation in presidents' opportunities to be responsive to the public. This effort has four core payoffs.

First, our approach to estimating presidential discretion has general and broad implications for expert surveys as a methodology for uncovering latent concepts. Using discrete choice experiments on expert panels has several appealing features. They are not time consuming for respondents and permit incomplete exposure to all items within raters. These features mean that the number of items – in this case, policy areas – can be increased without decreasing the likelihood of completion or limiting the reliability of the measure. For these reasons, this approach may also work well for samples of non-experts, and renders the results of such companion surveys more valid and directly comparable. This allows researchers to ask a straightforward, but often overlooked, question: how do the perceptions of experts and non-experts diverge for latent concepts like discretion? In Appendix A2, we describe a companion survey of the general public that will allow for comparisons of expert and public ratings.

Secondly, we provide the first systematic estimates of discretionary authority available to the president of the United States. Thirdly, we demonstrate that our estimates are associated with observed behavior in ways that provide novel support for theories of executive discretion and policymaking. We find that experts are united in their assessment that the president enjoys more discretion in foreign policy, relative to domestic policy. In addition, we found support for the proposition that discretion is associated with action, a relationship that holds across numerous measures of both discretion and action. These patterns are descriptive, but they lend support to each theory and demonstrate the validity of the measures. This work lays ground for future studies. Most obviously, our study only examines presidential discretion in the United States, but our approach is broadly applicable, and can be leveraged for comparative studies of presidential discretion – which we leave future work to pursue.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000296.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this paper can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PI2OVC.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions were presented at the University of South Carolina, the 2019 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association in Washington, DC and the 2020 annual meeting of the Southern Political Science Association, San Juan, PR. We thank Andrew Clarke, Marty Davidson, Thomas Gray, John Jackson, Bryan Jones, George Krause, Benjamin Lempert, David Lewis, Jacob Montgomery, Sara Morell, Brendan Nyhan, Sinead Redmond, Yuki Shiraito, Joel Sievert, Sharece Thrower, Jacob Walden, and Kevin Quinn for helpful comments and suggestions. Sebastian Leder Macek provided helpful research assistance. Shipan would like to acknowledge the support of the RSSS fellowship at the Australian National University. Special thanks to the panel of scholars who completed our survey. We are responsible for all errors.

Ethical standards

This research was determined to be exempt from IRB review (# HUM00159579).