The earliest accounts of Spanish encounters with the Indigenous inhabitants of the highlands recorded some extraordinary rumours. Conquistadors and early observers wrote that the plateaux and high valleys of the eastern range of the Northern Andes were inhabited by a people called the Muisca, ruled by powerful lords who sponsored lavish religious practices. There was talk of a great house ‘dedicated to the sun’, where ‘certain sacrifices and ceremonies’ took place, full of ‘an infinity of gold and stones’.Footnote 1 There were ‘temples in each town’, chapels in ‘mountains, paths, and diverse parts’, an impressive infrastructure of causeways and avenues, and a range of sacred ‘forests and lakes consecrated to their false religion’, sites of a variety of nefarious practices, including ‘sacrifices’ of blood and children. That every individual, ‘poor as they might be’, possessed ‘one or two or three or more idols’ – some, elaborate gold figures, others humbler wooden objects – which they carried with them at all times, even into battle. Although it was largely unknown to whom these buildings and sites were dedicated, or what purpose the rituals and paraphernalia served, one thing was certain: Early observers agreed that religion played a crucial role in the lives of these people. The Muisca appeared to be, in the words of one, ‘in their erroneous manner, extremely religious’.Footnote 2 That the authors of these early sources made this claim is easily explained: It was a common trope among Spanish observers of Indigenous societies around the New World and Southeast Asia keen to highlight their potential to embrace Christianity while underscoring the need for colonial rule and evangelisation.Footnote 3 Making sense of what they observed is another matter.

This chapter explores some of the contours of the religious practices of the peoples who came to be known as the Muisca in the early decades after the European invasion. This is not a straightforward task: It involves unpicking a series of powerful stereotypes, assumptions, and elaborations – fictions, some more rooted in reality than others – that emerged and became entrenched over the course of the colonial period in two distinct but interconnected registers of writing about the New Kingdom of Granada and its Indigenous inhabitants. The first is the influential corpus of materials produced largely for foreign audiences that comprised early descriptions, chronicles and works of history, important civil and ecclesiastical legislation, and key linguistic works; the second, the corpus of bureaucratic writing produced by local observers, priests, and bureaucrats in the service of colonial institutions. More subtly, exploring these practices also requires us to unpick some of our own assumptions about the functioning of religious traditions, economic production, social organisation, and political power among Indigenous peoples.

The picture that emerges is one of complex ritual practices deeply embedded in local contexts, where they performed crucial roles in the functioning of key aspects of everyday life for Muisca individuals and communities. This is a far cry from the visions of Muisca ‘religion’ in colonial texts and much of the historiography, and it is key to exploring how these groups would interact with the developing colonial church and its programme of evangelisation in the decades to come. To make sense of it, we need to start at the root of these misunderstandings.

Overlapping Fictions

Few early accounts of the European exploration and conquest of the region that became the New Kingdom of Granada have survived, and none were ever produced of the volume and scale of those from Mexico and Peru. Europeans had been active in the Caribbean coast of the region from the turn of the sixteenth century, but it was not until the late 1530s that they set about exploring the interior. The catalyst was news of the invasion of Peru, which prompted three expeditions – from Santa Marta in the north, Venezuela in the east, and Popayán in the south-west – that sought an overland connection from the Central Andes to the Caribbean. The first of these was an expedition south along the Magdalena River led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, which set off in April 1536, climbed the Eastern Cordillera and first encountered the Indigenous groups that inhabited its highlands, and culminated in the foundation of Santafé de Bogotá in August 1538.

There are only two known accounts by people involved in this expedition: One by Jiménez de Quesada and another by two of his men. The first is now lost, but was used in the sixteenth century by a number of authors as the basis for their own retelling of these events. The second, known as the ‘Relación del Nuevo Reino’, was a letter written by Juan de San Martín and Antonio de Lebrija from Cartagena in 1539, while they waited to return to Spain. The following decade two additional texts of disputed authorship appeared that narrated the Jiménez de Quesada expedition and described the inhabitants of the highlands. The first, which seems to have been composed between 1545 and 1550, is known as the ‘Relación de la conquista de Santa Marta y Nuevo Reino de Granada’ and may have also been written by one of Jiménez de Quesada’s men. The second is the more famous ‘Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada’, the authorship of which remains the subject of debate.Footnote 4

These first Europeans who arrived in the high valleys and plateaux of the Eastern Cordillera encountered a variety of agricultural societies, inhabiting a multitude of settlements of various sizes, and organised in different political configurations. As in other regions of the Andes, their basic units were matrilineal kinship groups – each with its own languages, resources, deities, and leaders – which had come together with others to form composite political units of different sizes, but without this resulting in the political unification of the region. Some of these composite groups were large and their leaders rich and powerful, such as Bogotá, whose name came to be given to the largest of these highland valleys, while others were more modest and their rulers less distinguished. This diversity and lack of centralisation surprised and disappointed the invaders, whose ambition was to find societies similar to those of Central Mexico and Peru, and who had great difficulty in understanding and explaining what they encountered on the basis of those models and expectations. One aspect that was particularly challenging was the religious landscape, as is clear from their earliest descriptions of these groups, which are full of rumours of rich temples full of gold and precious stones, run by a hierarchy of priests who performed frightening rituals.Footnote 5

The authors of these early accounts, like their contemporaries in other regions of Spanish America and South-east Asia, relied on categories and frames of reference derived from their European past and present to understand and describe what they observed. This is one reason why they identified Indigenous leaders with European princes and assumed that religious practices were performed by priests and directed to transcendental deities. However, they were also invested in presenting the disparate groups they encountered as a coherent and unified people, following the model of the Inca and Mexica, whose encounter by Europeans a few years earlier had motivated these expeditions. In fact, accounts of the expeditions of Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, and of the Indigenous societies they encountered, served not just as inspiration but even as practical models or scripts to imitate.Footnote 6 It is not surprising that their accounts, written in the model of the accounts of the expeditions of their more distinguished contemporaries, emphasised the prowess and bravery of the small band under Jiménez de Quesada and the power and sophistication of the enemy they faced.Footnote 7 Would-be conquering heroes, after all, needed fitting opponents, and to justify their actions, their struggle needed a moral and legal cause. It was for this reason that these early accounts also sought to cast Indigenous leaders as despots, drawing on established European discourses of good government, and contrasting the virtuous, Christian rule of the Spanish monarchy with the excesses of Indigenous tyrants.Footnote 8

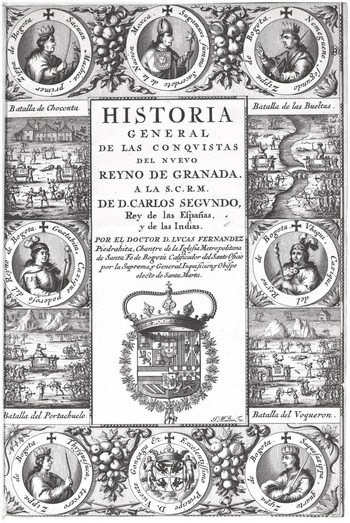

With time, these images developed in scope and ambition, as successive authors in New Granada writing primarily for foreign audiences, occasionally in collaboration with Indigenous elites, sought to render the pre-Hispanic societies of the region all the more impressive, in a bid to highlight the prestige of their homeland or in pursuit of other objectives.Footnote 9 By the late seventeenth century, these authors had produced richly detailed accounts of an imagined history of the Muisca before the arrival of Spaniards, complete with detailed descriptions of powerful centralised political structures culminating in two great kings – the Zipa of Santafé and the Zaque of Tunja – and a common, unified transcendental religion run by a hierarchy of priests. Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita’s 1688 Historia general of New Granada – in many ways the colonial culmination of this register of writing – was thus full of confident assertions concerning a Muisca ‘religion’ with a pantheon of deities, creation stories, and visions of the afterlife, led from great temples by high priests – some of whom were pictured, at great expense, in three richly illustrated title pages that accompanied his book (e.g. Figure 1.1).Footnote 10

The story of the Muisca has been one that has grown in the telling and retelling, and the stereotypes and images that came to characterise this register of writing have not been easy to dispel. Part of their enduring power is that they continue to be key to the way we Colombians have imagined the roots of our nation since independence. Since the early nineteenth century, generations of writers and scholars continued to reproduce and further embellish the claims of these colonial texts in works of history, theatre, and art, as the Muisca above all other Indigenous groups became integral to the construction of the identity of the Colombian Republic.Footnote 11 Still today, images of the Muisca and their material culture appear everywhere from banknotes to public buildings, as we continue to appropriate the Muisca – in the words of Carl Langebaek – as ‘the official “tribe” of the Colombian nation’ and a sort of ‘local version of the Aztecs and the Incas’.Footnote 12 In the process, the colonial circumstances of the production of these images and stereotypes have faded from view, and these elaborations have come to be taken as reliable reflections of the pre-Hispanic past, to the point of being used to inform not just historical research but even the analysis of archaeological and linguistic findings.

This has begun to change in recent years, but in piecemeal fashion. One important recent area of focus for historians has been the Spanish invasion itself, as recent works have questioned the traditional Eurocentric triumphalist story – found everywhere from the first accounts of the early expeditions, through seventeenth-century chronicles, to the nineteenth-century historical works that they inspired – of a small band of Spaniards, led by brave and pious leaders, overcoming overwhelming odds to ‘conquer’ the region in brief episodes of military conflict.Footnote 13 Another, as we will see shortly, is the notion of political centralisation among Muisca groups at the moment of contact. But the religious landscape described in this register of writing has received much less critical attention.Footnote 14

The influential, if increasingly fanciful, images of the Muisca and of the New Kingdom that can be found in this register of writing diverge from those of the second register that developed in the region over the colonial period: the internal documentation of the colonial bureaucracy. While the authors who wrote about the region and its supposed past for foreign audiences could ignore or gloss over local realities, those in charge of constructing colonial institutions and incorporating Indigenous people into colonial rule at a local level had no choice but to try to make sense of them, if only in order to overcome and take advantage of them. This began in earnest with the establishment of the kingdom’s civil and ecclesiastical government, with the arrival of the Audiencia of Santafé in 1550 and of the first bishop in 1553, which are the focus of Chapter 2.Footnote 15 By the time Fernández de Piedrahita’s Historia general was published in 1688, these local bureaucrats and missionaries had produced a large corpus of written sources that documented their continued interactions with Indigenous communities and individuals. These sources are no more objective than the writings of the chroniclers, but they do provide an alternative perspective from which to reassess a great many established ideas and stereotypes about Indigenous societies, and especially the Muisca, who, as the groups closest to the centres of Spanish settlement, received the greatest attention from colonial officials. The authors of this bureaucratic register of writing were no less reliant on imported categories and frames of reference than the chroniclers, and they too tended to assume, at least initially, that the Indigenous inhabitants of the highlands constituted a single ‘people’ or ‘nation’ with a common language, that Indigenous rulers worked in a manner comparable to European lords, and that Indigenous people constituted a pagan laity engaged in the worship of a demonic religion with temples, priests, and sacraments. In short, another fiction, perhaps less grandiose, but still far removed from local realities. Backed by the power of colonial institutions, and constituting the bulk of the colonial archive, this bureaucratic register constituted not only a privileged perspective on what it purported to describe but also in important ways a legal reality – what recent scholars of the New Kingdom of Granada have termed a papereality or a ‘kingdom on paper’, whose assumptions and explanatory power are all too easily taken for granted.Footnote 16

Despite these obstacles, recent scholarship on the Muisca from different disciplines has been scrutinising this second register of writing, alongside archaeological and linguistic findings, and offering new insights that allow us to explore the contours of Indigenous political and religious features at the time of first contact with Europeans and through the first decades of the colonial period. The result is a very different picture indeed: far from a unitary and homogenous society ruled by one or two great kings and with a centralised religion of priests and temples, the picture that emerges is a rich tapestry of enormous diversity and local specificity that deserves much greater attention.

Politics, Power, and Social Organisation

The starkest change so far in our understanding of the Muisca has concerned their political organisation and the power of elites. Among the chroniclers, early reports of the wealth and power of two important Indigenous leaders soon gave rise to the notion that the Muisca had been consolidated into two large kingdoms, led by the rulers of Bogotá and Tunja. This idea, first advanced in the 1570s by the Franciscan chronicler Pedro de Aguado, would reach its most elaborate colonial formulation in the work of Fernández de Piedrahita a century later, whose history of the two kingdoms included details of dynastic conflict, warfare, and intrigue between these two rival states.Footnote 17 The model of political organisation that emerged in these works, of an extremely hierarchical and centralised society organised into just two large political units, was enthusiastically taken up by historians in the nineteenth century and long remained influential, even as it shed its more obviously early modern terminology and the Muisca ‘kingdoms’ of the Zipa and the Zaque became ‘confederations’.Footnote 18

This model of two states has long been criticised, first as historians identified a handful of other large Indigenous polities and more recently as the consensus has moved further away from ideas of centralised political organisation altogether. Indeed, the latest research across a variety of fields suggests that the Muisca at the time of contact with Spaniards were organised into a large number of political units of different configurations and sizes. As in other regions of the Andes, all political units were at their core composed of basic matrilineal kinship groups that came together with each other in different ways to form composite units, which often came together again to form larger units still.Footnote 19 Scholars since the 1970s have argued that the larger Muisca political units were essentially nested amalgamations of subunits down to the level of the household, but recent research, especially the work of Jorge Gamboa, has moved further in emphasising that these associations were far more flexible and loose than previously thought, and that the component units were largely economically autonomous and self-contained – a situation that made them especially adaptable to changing circumstances.Footnote 20

As in so many other regions, the violence and disruption unleashed by the arrival of Europeans resulted in fundamental changes to the political landscape. The Spanish invasion of the Muisca territories, like those of other regions, was not a straightforward series of military engagements, but a gradual process that took shape over a prolonged period, made possible by the making and remaking of alliances with Indigenous groups. As a result of Spanish pressure, some of the larger conglomerations of Muisca political units – including Bogotá and Tunja, and many more – broke into their component parts in order to react efficiently to changing conditions.Footnote 21 Even what Spaniards saw as the most solid of political ties proved to be more flexible than they had anticipated. The ruler of Chía, for example, who had been observed to have an especially close relationship to his uncle Bogotá – as his subordinate and perhaps even designated successor – showed that he was willing to align himself with Spaniards against his superior when it suited his purposes.Footnote 22

Indeed, recent work on the history of this early period has begun to focus on the structural features of Muisca hierarchies that explain their inability to resist the Spanish invasion as a concerted whole, and at the same time allowed individual Muisca groups to realign themselves to best adapt to the changes that it represented.Footnote 23 This situation raises interesting questions concerning the mechanics of the imposition of Spanish rule elsewhere in Spanish America, because New Granada once again does not fit the model of other regions. On one hand, there exists the notion that the more sophisticated political apparatuses of the Inca and the Mexica rendered Peru and Central Mexico easier to dominate, because by capturing the Tenochca Tlatoani or the Sapa Inca Spaniards could hijack the political systems that they dominated; and on the other, the idea that political fragmentation and a lack of centralisation among Indigenous groups, such as the Mapuche, rendered regions more difficult to subjugate.Footnote 24 Neither model applies here.

From 1539, the Spanish arrivals began to assemble the institutions of colonial civil and ecclesiastical government. At its root, as elsewhere, was the system of encomiendas – grants of the right to collect tribute from Indigenous communities – which were distributed to individual Spaniards. As in other regions, these grants took advantage of the existing social and political structures of Indigenous communities, so that Muisca groups were assigned to encomenderos as self-contained political and economic units, each headed by an Indigenous ruler. Because some groups were still much larger than others, as in other regions, this process also involved simplifying and homogenising the diverse political landscape, ‘dismembering’ – as contemporaries put it – the larger political units into more manageable pieces, and identifying the rulers of each one, who were to collect tribute from their subjects and pay it up the chain to their encomenderos.Footnote 25

This started with the 105 encomiendas that Jiménez de Quesada granted his followers and collaborators shortly after the foundation of Santafé. By 1560, the records of the first visitation conducted by the Audiencia indicate that 171 encomiendas had been granted, composed of some 88,000 tribute-paying individuals and their families.Footnote 26 By the 1570s, by one estimate, all Muisca polities had been distributed to encomenderos. Initially, insurrections against the new encomenderos were common, but none surpassed the level of the purely local, of an alliance of two or three Indigenous leaders and their subjects, reflecting the political fragmentation of the region.Footnote 27 The effects of this reorganisation will be explored later in this book, but the point is that the basic building blocks of Muisca societies – the matrilineal kinship groups and the composite units of different configurations that they had long come together to form – not only remained in place, but became the foundations of the colonial tributary system.

To write of ‘kinship groups’ and ‘composite units’ may seem inelegant, but we lack a better political vocabulary to describe these different structures before the European invasion.Footnote 28 Spaniards at the time were less concerned with documenting and understanding Indigenous political organisation than transforming it for their own purposes. In addition to dismembering the larger composite units into distributable parts, Spaniards sought to simplify the complex political structures of different groups into something more akin to what they were used to seeing in other regions. After the initial work of political dismemberment was complete, Spaniards mapped a two-tiered system of political organisation on to Indigenous communities, labelling those leaders who seemed to govern whole groups ‘caciques’ and their polities ‘cacicazgos’ – a political vocabulary they had obtained and brought with them from the Caribbean – and those who governed only subordinate units ‘capitanes’, or captains, and their units ‘capitanías’, ‘parcialidades’ or simply ‘partes’, parts. This Spanish system of Indigenous political organisation rode roughshod over what were undoubtedly more nuanced and varied relations, but it would do for their purposes.Footnote 29

Positions of leadership and other responsibilities within the matrilineal kinship groups that made up Muisca societies were generally held by men but transmitted along matrilineal lines, usually from the incumbent to the eldest son of his eldest sister. At the same time, certain kinship groups played specific roles within the larger units of which they were part – including exercising leadership – so that specific positions in a composite group were transmitted within a specific component part.Footnote 30 This has long been known, but what has been much less clear is how Indigenous leaders maintained and exercised power over their communities and what their precise functions were, in large part owing to the distorting weight of imported stereotypes.

Early colonial sources wrote of the exaggerated reverence and shows of respect shown by the Muisca to their leaders, in part as an effort to portray many of them as tyrants in need of being deposed. The very earliest Spanish account of Muisca societies, by San Martín and Lebrija, told of how Muisca leaders were greatly revered, describing specifically how Bogotá was ‘honoured excessively by his vassals, because, truth be told, in this New Kingdom the Indians are greatly subjected to their lords’.Footnote 31 In this and later texts no one doubted that Indigenous rulers exercised power in a manner comparable to European princes. Indeed, as Chapter 3 explores, in Spanish law, Indigenous leaders were understood to be natural lords, whose power was derived from natural law and ancient custom. By the late seventeenth century, Fernández de Piedrahita and his fellow authors were writing of great Muisca kings and despots, of electors in the manner of those of the Holy Roman Empire, and of dukes and nobles in the manner of European aristocrats, whose hereditary power over subordinate groups was taken for granted.Footnote 32 These accounts and legal frameworks created the impression these figures exercised power in a manner comparable to how European lords held power over their subjects: controlling land, labour, and exchange.Footnote 33

Most recent research on the Muisca from across a range of fields has sought to reassess these ideas and better understand the foundations of the power of authorities. For example, archaeologists have, for some time, shown that political power among the Muisca was not based on direct control of fertile lands or labour, and that economic inequality between elites and the rest of the population was limited.Footnote 34 They note, for example, that the Muisca region is conspicuous among other areas of what is now Colombia for its lack of lavish burial offerings that could distinguish elite burials from those of commoners.Footnote 35 Archaeologists have also found little evidence that elites could appropriate resources to the point of resulting in nutritional problems among the rest of the population in times of dearth, further questioning the notion that political power was based on economic disparities.Footnote 36 Indeed, most recent archaeological research coincides in highlighting that the basic units that composed Muisca polities were to a very great degree economically self-sufficient, and that the leaders of the larger political units that they formed had little direct control over production.Footnote 37

It is difficult at first sight to understand the position of Indigenous authorities in their societies in light of this evidence, but as scholars have reassessed the relative importance of factors such as the control of land and labour in explaining the place and role of Indigenous authorities, other elements have become more prominent – especially those related to their ritual and religious practices. Indeed, the records of civil and ecclesiastical visitations and inquiries carried out among different Muisca groups over the course of the sixteenth century reveal how it was the sponsorship and administration of the sacred that was at the root not just of the position of authorities, but of the very functioning of economic production and exchange. To understand how, it is best to see it action.

The corpus of colonial sources that describe Indigenous religious practices is not vast or systematic. As we will see, changing attitudes among the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of New Granada concerning the most effective means of Christianisation in the seventeenth century meant that they launched few enquiries to investigate Indigenous religious practices, and certainly nothing as systematic as the punitive inquisitorial models that emerged in the centres of empire.Footnote 38 What they did produce, however, provides revealing glimpses of the existence of complex and multi-layered practices, firmly rooted in local communities and kinship groups.

Ritual Economy and Leadership

On Christmas Eve 1563, news reached Santafé that a great ceremony was taking place in an Indigenous town some thirty miles to the south-east of the kingdom’s capital.Footnote 39 Reports stated that large numbers of people had been summoned by Ubaque – the ruler of the community and town of the same name – who had called together not only his subjects but also the leaders and representatives of multiple other groups from as far afield as the province of Tunja, and even some of the Indigenous inhabitants of the city of Santafé.Footnote 40 Even though the majority of Indigenous people involved were not Christians, the authorities were especially concerned about the deleterious effect that the celebrations would have on those who were.Footnote 41 There was talk of feasting, dancing, and processions for ‘the cult and veneration of the devil’ and even of ritual homicide, all on the capital’s doorstep and – as the authorities repeatedly noted – at Christmas of all times, ‘in mockery of the mysteries of our holy faith’.Footnote 42 The Audiencia took it upon itself to investigate, dispatching one of its members, the oidor Melchor Pérez de Arteaga, to the town.Footnote 43 That it was a civil authority and not an ecclesiastical one that was investigating these allegations is significant, as we will see, and a reminder that the authority and leadership of the church over the religious affairs of the kingdom would take years to be consolidated. The proceedings at Ubaque were to be the last large public religious celebration held openly by a Muisca group that was recorded by Spanish observers.

Pérez de Arteaga arrived in the town three days later to find that the celebrations were still ongoing. A great number of people were present, certainly hundreds and perhaps even thousands, including a number of Indigenous leaders, caciques and captains from around the region – from communities such as Suba, Tuna, Bogotá, Cajicá, and Fontibón, which we will be visiting later.Footnote 44 One Spanish official reported that there were as many as five or six thousand people present, while another explained that these barely amounted ‘to a third of the Indians who were expected to come’.Footnote 45 Most of the people were ‘singing and dancing with banners’, processing in groups along a long causeway marked off in front of the cacique’s cercado, his residential compound, which had been decorated with feather standards. Each group carried ‘banners before them and [were] dressed in different ways’, some wearing masks and headdresses, ‘playing flutes and conches and other instruments’ and ‘singing sorrowful songs in a language that could not be understood’.Footnote 46 The groups of dancers were observed processing along the causeway and entering the cacique’s compound, where the celebrations continued, in particular the consumption of food and drink. Pérez de Arteaga called the caciques together and told them to stop, and persuaded them, ‘with gentle words’ to remain in the town and not to hide or dispose of the objects they were using, so that he could investigate. Or so he recorded in his account of the proceedings.Footnote 47

The following day, when the celebrations finally stopped, Pérez de Arteaga was able to interrogate a number of Indigenous leaders and to confiscate a large number of masks, musical instruments, gold jewellery, and feather adornments. He later had a number of buildings that seemed to be integral to the celebrations destroyed, and took a number of caciques and other people with him to Santafé for further interrogation.Footnote 48 That he was able to do this is extraordinary given the vast disparity in numbers between those present and the oidor and his entourage, but it is not easily explained by the documentation itself, which takes the imposition and efficacy of Spanish power for granted. In addition to participants in the celebrations, Pérez de Arteaga also interrogated Spanish observers in Ubaque and, back in Santafé, a number of other Indigenous leaders who had apparently refused to attend despite being invited. The investigation continued into the early days of 1564, but was dropped after the continued detention of Indigenous rulers resulted in a strike among labourers working on the construction of the cathedral of Santafé, who refused to work whilst their leaders were detained. A few days later, bishop Juan de los Barrios persuaded the Audiencia to release the prisoners so construction could resume, and the records stop.Footnote 49

The report of Pérez de Arteaga’s investigation is an intriguing document, testimony to the attempts of Spanish authorities to understand what was taking place and the issues this involved, and to their efforts to make sense of the diverse perspectives of the people they interrogated. Part of the confusion arose from the fact that even though the authorities described the celebration as a single event, the celebrations actually comprised a variety of individual practices related to different aspects of the community’s life, including several to do with the agricultural cycle and others with succession to the office of ruler and the preparation of the next incumbent. Many of these elements would be documented in other sites around the region in greater detail over the following decades. For this reason, the events of Ubaque in 1563 provide an excellent starting point for examining some of the workings of a number of different practices.

A good place to start is the feasting and drinking that so concerned Spanish observers. The proceedings of Ubaque, in common with a broad range of Indigenous celebrations in New Granada and elsewhere, were described by Spanish authorities with the denigrating terminology of ‘borrachera’ or drunken revelry, as an expression of Indigenous intemperance and an affront to natural reason. This was a very old trope in Christian writing about non-Christians, present from early critiques of so-called pagans in the Mediterranean in late antiquity.Footnote 50 Augustine, for example, identified drunken excess as one of the hallmarks of the influence of false deities, denouncing drunkenness as means through which they induced their worshippers ‘to become the worst of men’.Footnote 51 As with so much of the late-antique Christian repertory on paganism, drunkenness looms large in early modern characterisations of Indigenous people across the New World.Footnote 52 That it was a Spanish obsession, however, should not distract us from recognising the importance of the consumption of certain foods and drink in celebrations of this sort. These were much more significant than Spaniards realised, if for different reasons.

Pérez de Arteaga recorded seeing large numbers of gourds and other vessels of chicha, maize beer, provided by Ubaque to his guests, and the consumption of this beer was clearly central to the celebrations.Footnote 53 Indeed, Indigenous witnesses reported that this was one of the principal reasons they had come. Riguativa, a captain from the town of Fontibón, reported that he had been invited ‘to celebrate and to drink’, and explained flatly that ‘this is why this witness had come to the town of Ubaque’. Others reported that Ubaque had promised them gifts as well. Xaguaza, the leader of Tuna, explained that Ubaque had ‘said he would give [him] gold and mantas’, blankets of cotton cloth.Footnote 54 But what was behind Ubaque’s largesse?

Celebrations of this sort were not unusual. Indeed, Spanish witnesses reported having seen multiple celebrations in Ubaque alone. Nicolás Gutiérrez, who lived nearby, explained that he had seen ‘three borracheras like this one now’, even if none had been ‘as solemn as this’.Footnote 55 Observers coincided in saying that what made this ceremony so striking was its scale. Even older Indigenous witnesses explained that they had never seen anything like it since the days of the old ruler of Bogotá, before the Spanish invasion.Footnote 56 This seems to have been deliberate. The statements of Spanish and Indigenous witnesses, and Pérez de Arteaga’s record of the many distinguished Indigenous leaders who participated, make it clear that the celebration at Ubaque in 1563 was, on an important level, a bid for regional pre-eminence and a display of wealth before other regional leaders, including the successor to the now less prominent polity of Bogotá.Footnote 57 When questioned, Ubaque eventually explained that it had taken him six months of planning.Footnote 58 It was clearly an investment of significant labour and resources in a bid for regional pre-eminence. But how to pay for all of this?

The answer is that this was not a one-way exchange. When Ubaque was interrogated, he explained that he had also received gold and other gifts from the participants. ‘Each cacique and captain who came’, he explained, ‘has given a piece of gold, some worth 10 pesos and some worth 5’.Footnote 59 When asked about this, some Indigenous witnesses confirmed they had brought gifts. Chasquechusa, described as a captain of Bogotá, reported having brought Ubaque two mantas.Footnote 60 This was not simply a display of generosity, but an occasion for exchange, and through this exchange for the making and remaking of political allegiances in a period of profound political change.

These gifts aside, it was clear even to Spaniards that it was the community of Ubaque that had provided the resources and labour for the celebration. News of the celebrations had reached Santafé through a number of Dominican friars active in the area, including one Francisco Lorenzo, who testified before Pérez de Arteaga. His testimony is a litany of the regime’s worst fears – ritual homicide, adultery, incest, the summoning of demons, and dancing – but it also expressed concern about the misuse of the community’s resources by Ubaque. Lorenzo explained how these sorts of celebrations involved the collection of vast amounts of ‘mantas, gold, and maize’, which, he speculated, probably placed an unsustainable financial burden on Ubaque’s subjects and would doubtless cause them to flee the town to escape their ruler’s unreasonable demands.Footnote 61 Viewed through the lens of European political categories, the celebration was understood by Spaniards to be an expression of excess and ill government by the ruler at the expense of his subjects. This perspective was clear in Pérez de Arteaga’s questions to Spanish witnesses, which asked them specifically to comment on ‘whether they know Ubaque to be evil and perverse and idolatrous’. As one apparently replied, ‘these borracheras can only be at the expense of innocents’.Footnote 62

Spaniards took for granted the power of Indigenous leaders to compel their communities to work and to provide them with resources. So ingrained was their understanding of Indigenous leaders as natural lords that they built the colonial tributary system on the assumption that these figures had the power to require their subjects to pay and to work. Lorenzo and other Spaniards gave little thought to how Ubaque had mobilised his subjects, and Pérez de Arteaga never thought to ask them. Instead, the proceedings only served to confirm their assumptions about the tyranny and despotism of Muisca leaders. What they failed to see was that the celebration itself was integral to Ubaque’s ability to mobilise his community.

The timing of the celebration, which so offended the authorities, provides a clue. While news of the proceedings only reached Santafé on Christmas Eve, by the time Pérez de Arteaga arrived it was clear that it had been going on for several days. They had begun around the time of the winter solstice, 22 December 1563, which marked the beginning of the dry season, when work on raised beds and planting took place, before the rains resumed in March.Footnote 63 In fact, a crucial aspect of the proceedings involved preparation for the agricultural cycle ahead. Witnesses interrogated at Ubaque mentioned that celebrations of this kind took place precisely for the preparation of fields, raised beds, and irrigation canals. Indeed, in his testimony, the Spaniard Nicolás Gutiérrez explained that although some ceremonies, in his view, were held ‘to invoke demons and for idolatry’, Indigenous leaders also held feasts for the community ‘when they dig’, preparing ditches and raised beds for planting. Gutiérrez remarked that although idolatrous practices should of course be banned, the latter should be allowed because these ‘have no purpose other than eating and celebrating and working and no other thing’.Footnote 64

Gutiérrez’s observations are corroborated by a significant body of complaints by Indigenous leaders half a century later, when they turned to Spanish authorities to complain that their subjects had by then ceased to perform this essential labour. Significantly for them, this was not just how leaders had directed communal efforts, but how they had survived: it was in exchange for the provision of food, drink, and certain special products that their subjects had built and maintained their leaders’ residential compounds, planted their food, and harvested their crops. This was made clear, for example, by don Pedro, the cacique of the town of Suba, who in 1605 explained to the authorities that Muisca caciques obtained labour and tribute from their subjects in exchange for their provision of banquets and celebrations.Footnote 65

The practice of feasting has long been seen by archaeologists as an indicator of the emergence of elites.Footnote 66 In the case of the Muisca, archaeological research shows that feasting intensified in many regions during the Early Muisca period (800–1200 CE), as evidenced by the appearance, in ever growing numbers, of vessels for the preparation and consumption of chicha among archaeological findings.Footnote 67 But how this relates to political and economic centralisation has been a matter of debate. Some scholars have taken the growing prevalence of feasting as evidence that Muisca societies grew increasingly centralised and their elites better able to exercise control over economic production, using their control over land and labour to produce the food and drink provided at these celebrations.Footnote 68 Indeed, some hold that feasting was a key mechanism through which these elites attained this economic centralisation.Footnote 69 But more recent analyses of archaeological evidence of feasting in pre-Hispanic Muisca societies suggests there was no positive correlation between evidence of feasting and control of land or labour, and that it could instead be related to a broader range of social processes – not least serving as occasions for Muisca leaders to justify their pre-eminent positions.Footnote 70

Informed by work on Indigenous authorities elsewhere in the Andes, archaeologists have for some time been arguing that the principal role of Muisca leaders was redistribution. Far from controlling the means of production and appropriating surpluses for themselves, Muisca leaders received goods and services from their communities, and their neighbours, which they then returned to them through mechanisms of redistribution – in a way that is comparable, if smaller in scale, to what occurred in other Andean societies. In the late 1980s, for example, Langebaek argued that Indigenous leaders were ‘specialists in the storage and distribution of communal surpluses’ to satisfy collective needs, and valuable intermediaries performing essential functions.Footnote 71 These ‘collective needs’ could be broad, and also included the organisation and direction of communal efforts for a range of purposes.Footnote 72 How this redistribution worked, and how Indigenous leaders inserted themselves in the centre of these exchanges, was less clear.

Recent research by anthropologists and historians on colonial records such as those of the celebrations of Ubaque has been throwing important light on this question. The latest work on the distribution of land, labour, and resources among the leaders of the different groups that composed each Muisca cacicazgo in the first decades of the colonial period has been highlighting the inability of Indigenous leaders to exercise direct control over the economic affairs of their communities.Footnote 73 The documentation of visitations, tax assessments, and population surveys in this period show very clearly that the groups directly under the control of Indigenous rulers – that is, what Spaniards called the parcialidad or parte of the cacique – tended not to have the largest populations, control over the largest parcels of land, or the greatest economic production. On the contrary, in many cases they were smaller and poorer than the parcialidades of other community leaders, the people Spaniards called capitanes, who were somehow still their subordinates.

As Santiago Muñoz Arbeláez’s work on the valley of Ubaque has shown, this was not a simple matter of numerical inequality, but one of specialisation. A civil visitation carried out in the nearby town of Pausaga in 1594, for example, recorded that the community there was by then composed of ten parcialidades, nine of which were headed by captains and the tenth by the cacique.Footnote 74 Of these, the cacique’s was, with one exception, the smallest. But what these detailed records reveal is that most of the adults of the cacique’s group were ‘indias del servicio’, female servants, and other women, while none were ‘indios útiles’, or working men, in contrast to the other parcialidades, most of which had no ‘indias del servicio’ and all of which had large numbers of working men. What Muñoz’s analysis shows is that these women were specialists in the production of chicha and other special foods, and that this production was concentrated in the parcialidad of the ruler – something he also observed in Ubatoque and other towns in the area.Footnote 75 This growing specialisation is corroborated by the archaeological record, which shows that the brewing of chicha and the preparation of certain foods consumed in feasts – such as deer meat – came to be concentrated in elite dwellings from as early as the Early Muisca period (c. 800–1200 CE), even as it shows that it did not result in nutritional deficiencies among the rest of the population, suggesting that the food prepared in these sites was consumed by the broader community as well.Footnote 76

This is what was happening in Ubaque in 1563. It was the community that provided the maize and the raw materials for the celebration, which the cacique processed in special ways and distributed back to the community – and in this case also to neighbouring elites. In exchange, the community also came together to perform works of communal labour for the benefit of all, such as the building of raised beds for planting and channels for irrigation. Moreover, as Gutiérrez’s distinction suggests, the communal labour performed on these occasions could be limited to infrastructure and agricultural work – as was also the case in Suba in 1605 – but it could also go beyond this. Indeed, at Ubaque in 1563 the proceedings also involved the performance of ritual labour, not least divination of the agricultural cycle ahead. As Gutiérrez also explained, an individual, dressed all in white, was placed on the causeway that had been constructed outside of the cacique’s compound, along which processions took place. He stood there from sunrise to sunset, and if he remained perfectly still it was a sign that it would be a fertile year. ‘If he moved’, the witness added, ‘there is to be hunger’.Footnote 77

The other activity closely associated with Indigenous leaders and their immediate kinship groups around the Muisca region was the production of special dyed and painted cotton mantas (e.g. Figure 1.2). The raw materials for these were the cotton blankets that so many of these communities produced. The production of mantas was such an important part of the regional economy that cotton cloth was one of the basic units of exchange in which colonial authorities set the standard rates for the payment of the tribute owed by these groups to their encomenderos, and through them to the crown. These textiles were woven by members of individual kinship groups and collected by their leaders, who paid them up the chain to leaders of the composite units to which their groups belonged, all the way to the ruler. In exchange, the ruler returned a portion of these mantas to other community leaders, but only after having had them decorated and painted by carefully controlled specialists. In 1594, as Muñoz noted, don Antonio, cacique of Pausaga described how this system worked. Before the coming of the Spaniards, he explained, the captains had paid the cacique ‘fifteen or twenty mantas’ in tribute, while commoners had paid him ‘one or two, according to their ability, and in addition to this tribute did his planting and [constructed] buildings and cercados’. In exchange, the leader marked the captains with a dye, ‘which was an honour among them’, presented them with ‘one painted and one coloured manta’, and provided commoners and captains alike with food and drink.Footnote 78

Figure 1.2 Painted textile fragment of luxury blanket (manta), Colombia, Eastern Cordillera, 800–1600 CE (Muisca period). Museo del Oro, Banco de la República, Bogotá. 35 x 59.5 cm. T00054.

This brief description from Pausaga may be one of the clearest explanations of the functioning of these exchanges, but we can also see examples of these practices throughout the Muisca region. In Ubaté in 1592, don Pedro, the cacique, explained how he had heard that in the old days, each captain would pay ‘4 or 5 mantas and 2 or 3 pesos, and common and ordinary Indians would pay one plain manta and half a peso of gold and work our fields and build our houses and cercados’. In turn, ‘the captains would receive one painted manta in recompense, called chicate, and the rest would be fed and given deer meat’.Footnote 79 In 1594, in Fontibón, some eight miles to the west of Santafé, witnesses explained that individuals close to the cacique were trained in the decoration of ‘good and rich’ mantas, which were then given by the cacique to select individuals, along with other objects and special foods, as they put it, ‘in confirmation of office’.Footnote 80 These could only be granted by Indigenous leaders in specific ritual contexts, and could only be used or consumed by the individuals whom they chose. Everyone else, the witnesses explained, was forbidden to wear or use them. The same was the case with the food that was prepared and distributed by the caciques. The community provided the ingredients, but only the cacique and his household could transform them into the special foods and drink served at the feasts. As don Antonio Saquara, the leader of Teusacá, explained in 1593, the preparation of special food, which in his household was done by six women, ‘is the custom and authority of caciques, so that we may be obeyed’.Footnote 81

In other words, Muisca leaders may have lacked direct control of the means of economic production, but they maintained a monopoly on key means of ritual production, and this was central to their position at the head of their communities, and a key instrument through which they projected their power beyond them. This is what rendered the asymmetrical exchanges that were at the centre of community life, and which were the foundation of political hierarchies, – in an important sense – symmetrical.

These conclusions are supported by a careful reading of the final series of practices that Pérez de Arteaga’s report documented at Ubaque in 1563, which were to do with the office of the ruler itself. There, some of the proceedings appeared to be related to the succession of the office of leader of Ubaque. They centred around a special building, described as a coyme, where the heir to Ubaque was said to prepare for his position, and the celebrations also involved an aspect of mourning for the current incumbent, even though he was still alive.Footnote 82 Rumours circulated about what occurred in the interior of the building, not least because few witnesses had any experience of what went on inside. A priest active in the area, Francisco Lorenzo, claimed that coymes were ‘houses of their sanctuaries’, where the Muisca buried deceased notables, and speculated that the buildings were also the sites of grisly sacrifices – something akin, in short, to an inverted Christian church.Footnote 83 Spaniard Nicolás Gutiérrez, for his part, claimed it was the site of the most excessive drinking, that he had heard it was where the devil himself appeared before them and gave them instructions.Footnote 84 Armed with this information, Pérez de Arteaga asked Indigenous witnesses to confirm whether ‘some idolatry’ had taken place inside, and particularly whether they had summoned the devil – confident, as ever, in the universality of these Christian categories. Eventually Susa, the elderly leader of a nearby community of the same name, disappointed the Spaniards by explaining that it was something much less scandalous. It was for the preparation of Ubaque’s heir: ‘the heir is put inside for six years’, he explained, and ‘does nothing more than sit by the fire, and that there is no drinking or summoning of the devil’. This, he added, ‘is the truth, as I am too old to lie’.Footnote 85 As it would turn out, this sort of ritual enclosure for an extended period followed by celebrations was not unique to this incident. What was unique, as so often with this case, was its scale.

Accounts of this practice of ritual enclosure abound from the earliest European accounts of the Muisca. Even the anonymous author of the ‘Epítome’ explained that ‘those who are to be caciques or captains … are placed when they are young in certain houses, [and] enclosed there for some years’, depending on the office they were to inherit.Footnote 86 In 1569, when the Audiencia sent someone to investigate allegations of illicit ritual practices among the people of Suba and Tuna, a few miles north-west of the city of Santafé, a variety of witnesses described how the caciques and captains of the town made use of these structures to prepare their successors for office.Footnote 87 There was disagreement as to how long the individuals concerned remained enclosed, and what they did whilst inside, but witnesses agreed that great celebrations took place when the process came to an end.Footnote 88 Without this ritual enclosure, they asserted, they could not succeed to the office.Footnote 89 In the town of Tota, some forty miles west of Tunja, witnesses interrogated in 1574 described a similar celebration. One explained how there was someone currently enclosed, but that the period of enclosure was to come to an end at the time of the upcoming maize harvest. Then, the cacique would hold a great celebration, for which he had ‘prepared much maize and called together all the land’ and had readied ‘many feathers and adornments for the said celebration’.Footnote 90

The clearest description of the purpose of this ritual enclosure comes from the report of an investigation carried out by the Audiencia in 1594 in the town of Fontibón. The report, compiled on the basis of the declarations of a number of Indigenous witnesses, makes it clear that at least there it was not only Indigenous rulers who were enclosed, but that this was also a means by which other individuals were prepared for other positions of responsibility.Footnote 91 For example, witnesses described how these buildings were where certain ritual practitioners, described as xeques, prepared their nephews to become their successors.Footnote 92 Those who were to become xeques, the report explained, were placed in these buildings in groups of three or four, from around the age of ten, where they were to remain enclosed for four or six years. Far from the drunken excess that witnesses in Ubaque imagined, they spent this time observing a strict diet, ‘eating very little, and with no salt’, and limiting their foods to ‘toasted maize and small potatoes, which have little substance, and some wild leaves’, and ‘drinking chicha only once a day, and very moderately’, all of which was provided through a small hatch cut into the building. Their only visitors were ‘their uncles, the old xeques whom they are to succeed, [who] give them their law and teach them how to make their sacrifices and burnt offerings’. Crucially, the report explains, they also ‘teach them how to paint and weave mantas of the good and rich kind that they make’.Footnote 93 In 1608, similar practices were described by Jesuit observers in Cajicá, who also associated them with the training of Indigenous ‘priests’.Footnote 94 In both cases, the conclusion of the period of enclosure was followed by celebrations and additional rituals by which local rulers confirmed the practitioners in their office.Footnote 95

These xeques, and the broader effort of colonial authorities to identify Indigenous priests, will be scrutinised later, not least because they became a recurring obsession of colonial officials. For now, it is key to note that these practices of ritual enclosure were the means through which Indigenous leaders and their close associates acquired the knowledge and status that allowed them to produce the special mantas and organise the celebrations that were central to the functioning of the ritual economy that powered production and exchange in their communities, and which was central to their social and political hierarchies.

Other mainstays of the received image of a centralised and homogenous Muisca society also take on a new significance with these considerations in mind. The protocol and distance observed by the Muisca towards their rulers that so concerned early observers is a good example. Shortly after first contact, San Martín and Lebrija had observed that the Indigenous peoples of the highlands were ‘greatly subjected to their lords’. A few years later, the anonymous author of the ‘Epítome’ added further details, explaining how the Muisca were forbidden from facing their caciques when addressing them, and also had to offer other elaborate marks of respect and submission.Footnote 96 This treatment of Indigenous leaders was corroborated by a multitude of observations in colonial records. For example, when the enemies of the controversial mestizo don Diego de Torres, cacique of Turmequé, sought to support their assertion that he was encouraging his subjects to rebel against Spanish rule and to turn away from Christianity in 1564, they claimed that he ‘made them turn their backs [to him] following their ancient rites, and does not face them when he talks to them or allows them to look him in the face’, in a manner befitting ‘caciques who are not political or Christian’.Footnote 97

It is not surprising that descriptions of these Indigenous customs contributed to the impression that Muisca rulers were despotic, because they were intended by Spanish observers to do just that, contrasting this Indigenous despotism with righteous government under Spanish rule. From the 1560s, Spanish authorities began to attempt to ban what they perceived as these exaggerated customs in successive rounds of visitations in an effort to bring Indigenous leaders more in line with their own conceptions of righteous and legitimate rulers should behave, for the sake of political stability. But given what we now know about the dynamics of the power of Indigenous authorities, and of the real distance – at least in economic terms – between them and their subjects, these behaviours take on a different significance. They are less the marks of vassalage and tyranny, and more the symbolic means through which an Indigenous political and economic order, with strong ritual dimensions, was made material. And it was on these non-Christian ritual foundations – which the authorities were already working to undermine – that colonial government and the colonial tributary economy, through their reliance on Indigenous leaders, were actually built.

Muisca ‘Priests’, ‘Temples’, and ‘Sanctuaries’

It should already be clear that these highly localised ritual practices are a far cry from the depictions of Indigenous religion in colonial historical texts, such as the writings of chroniclers like Fernández de Piedrahita. But reading administrative records such as those of Pérez de Arteaga also shows that bureaucrats and missionaries also tended to misunderstand Indigenous religious practices by relying on imported frames of reference. In this way, they tended to assume that religious practices were the province of a small and specialised section of the population, a clergy, whom they labelled xeques or ‘sorcerors’. In the language of a typical report, such as that prepared by the oidor Miguel de Ibarra after carrying out an investigation in Fontibón in 1594, the Muisca were thought to hold these xeques ‘in the same reverence as Christians do their bishops and archbishops’.Footnote 98 This hierarchy of priests, bishops, and archbishops, based in temples consecrated to the devil rather than to God, were assumed to carry out ‘rites and ceremonies’ in a manner that was the inverse, but otherwise entirely similar, to their Christian counterparts.Footnote 99 These ideas were taken up by colonial chroniclers, who further elaborated these assumptions, just as they did with Muisca rulers. For example, writing in the 1570s, the Franciscan chronicler Pedro de Aguado (born c. 1538) described how they were ‘held in great veneration and feared spiritually and temporally’ by the Muisca, even by caciques, because they exploited their anxieties with ‘great fears and threats of the punishment of the wrath of their gods’.Footnote 100

These images of Muisca religious leaders were in part a reflection of the very well-established Christian tendency to focus on false prophets and perceived corrupters of the flock, which was influential across a multitude of missionary theatres.Footnote 101 Confronted with the unknown and unfamiliar, early modern Spaniards reached for familiar concepts, confident in the applicability of the categories and frameworks of biblical and classical sources and Christian history, which held themselves to be universally applicable.Footnote 102

The assumption of commensurability is ubiquitous in colonial documentation, and it was often even ascribed to non-Christian Indigenous witnesses by translators and scribes. For example, in Ubaque in 1563, Xaguara, the leader of Tuna, was asked whether ‘in that building they summoned the devil’, referring to the coyme, and was recorded saying that ‘he believed that they summoned him because that is the custom among them’ – or at least that was what was written by the scribe Luis de Peralta on the basis of the translation of the interpreter Lucas Bejarano. Ubaque himself, when asked why he had organised the celebration, through the same interpreter and scribe, was recorded to have said ‘that when God made the Indians he gave them this as their Easter, as he gave the Christians their own’.Footnote 103

It is not that Spaniards were blind to the fact that that Indigenous people perhaps might not be familiar with European concepts and categories. Records of conversations with Indigenous people in this early period generally relied on translators, especially when witnesses were not Christians and had little contact with Spaniards and colonial institutions. Because the documentation recorded the answers given by the interpreters, who were sworn to render an accurate translation, and never the responses of the Indigenous witnesses themselves, the work of translation itself is generally rendered invisible. We generally do not know how translators explained concepts and ideas or how these were received and understood by Indigenous witnesses. Indeed, as we will see, surviving bilingual works such as vocabulary lists and more elaborate dictionaries all date to a later period, and most to the seventeenth century. But a handful of records do make visible some efforts to determine the accuracy of communication.

Visitations carried out by the Audiencia in this same period in regions further removed from the centres of Spanish settlement, such as the northern reaches of the province of Tunja, show a clear sensibility to the fact that key concepts might not be universal. In his 1571 visitation of the encomiendas held by Jiménez de Quesada, for example, the oidor Juan López de Cepeda needed to determine how many mantas and other products local communities paid Jiménez de Quesada, and how this compared to the rates that the Audiencia had set. In each case, when questioning local Indigenous leaders, Cepeda was not content simply to record the numbers and quantities that the translator relayed. In Pisba, for example, when a group of captains explained that each year they paid twenty mantas, Cepeda made sure that they were all on the same page. ‘They were ordered to take kernels of maize and count out 20 kernels’ in front of him, ‘and they said that this was 20’. To be certain, the scribe recorded in the margin ‘they know what 20 is’.Footnote 104 He repeated the procedure each time: ‘captain Sasa said he has 23 Indians … using 23 kernels of maize; Captain Yuramico said he has 36 Indians who are his subjects … which he said with 36 kernels of maize’. All the accounts were accurate, the scribe recorded, because ‘the said caciques and captains said it and gave accounts in maize’.Footnote 105 They repeated the procedure time and again.

Cepeda recognised that there might be difficulties communicating something as basic as a measurement, and took pains to ensure that the records his visitation produced were accurate. But he also took for granted the universality of religious concepts. These same witnesses, whom we are told again and again were not Christians and could not speak Castilian, were nevertheless asked whether they had ‘sanctuaries and sacrifices’, and whether ‘they speak to the devil’. The intelligibility of these concepts was taken for granted. Often Indigenous witnesses were recorded saying that they did not. Others, like Quesmecosba, captain of Tabaquita, in Pisba, went a little further, explaining that ‘they do not have sanctuaries, that they are poor, and that there is no gold in their land’, suggesting he had caught on to what the authorities were really after.Footnote 106 Clearest of all was Atunguasa, cacique of Mama, who explained that ‘he does not know what a sanctuary is’.Footnote 107 No matter: Cepeda continued asking after them, ordering ‘that those who are not Christians become so’, and commanding them ‘to leave their evil rites and ceremonies’, whatever those might actually turn out to be.Footnote 108

The reality was rather different, and to appreciate it we need to look at a broader range of colonial documentation. The great celebrations that took place in Ubaque in 1563 were to be among the last of their kind. Perhaps the last was a smaller celebration that took place in the town of Tota, news of which reached the authorities in 1574, in a suit between the Indigenous leader and his encomendero, who reported having stumbled upon a celebration in which he claimed some 2,000 people from around the region participated.Footnote 109 One witness explained that it consisted of three or four days of dancing and various ceremonies in the cacique’s cercado, which included sorrowful chanting.Footnote 110

As in other parts of the New World, these large, public celebrations were the first to succumb to colonial pressures.Footnote 111 Early rumours of a regional network of hidden temples and of trade in child victims for ritual homicide, so common in the first texts about the Muisca, disappeared from the written record by the time the Audiencia arrived in 1550.Footnote 112 They continued to be considered in successive chronicles, but do not appear in the documentation of the colonial bureaucracy, beyond questions asked of Indigenous witnesses by officials like Pérez de Arteaga, who were sorely disappointed. Instead, the records that he and his colleagues produced show glimpses of increasingly modest, but no less important, religious practices.Footnote 113 This was not simply because colonial pressures made large-scale celebrations increasingly difficult, but because the religious practices recorded as the colonial period developed came to be set in the context of the smaller social and political units that replaced what larger conglomerations had existed before the arrival of Spaniards.Footnote 114

The core of Muisca religious practices – at least in a number of instances for which documentation survives – appears to have been the interaction of individuals and kinship groups with deities or metapersons that Spanish observers described as santuarios. The records of colonial officials mention only one by name, Bochica, who appears on three occasions in the proceedings of 1563, as a santuario belonging to Ubaque. Bochica was variously described by witnesses as a building, which Pérez de Arteaga had destroyed, as the father of a ‘tiger’ – perhaps a puma or jaguar – that had recently been attacking travellers on local roads, and as an ‘idol’. When asked who Bochica was, Ubaque replied that ‘he is a wind’ – ‘un viento’ – and that he was in the site of the building that the Spaniards had destroyed.Footnote 115

Bochica aside, all the other santuarios of the colonial record appear to have been lineage deities that inhabited portable objects. Although the term santuario can be translated as ‘sanctuary’, and the near-contemporary Sebastián de Covarrubias defined the term as ‘a religious place’, santuarios were not sites or buildings, as Spaniards generally expected.Footnote 116 They varied somewhat in shape and composition, but shared some basic characteristics. Each was the figure of an ancestor and was firmly rooted in the kinship group that maintained it. They fulfilled a range of purposes and were integral to the identity of its group and its grounding in a particular location. Just as some of the kinship groups that formed part of a particular Muisca polity occupied a position of responsibility or leadership over the rest of the composite whole, some santuarios had spheres of action that embraced entire communities. And, naturally, there were differences in the use to which these practices were put by different groups within Muisca communities, most obviously Indigenous leaders, who used them to cement and enhance their prestige and authority. To understand their operation, it is best, once again, to consider them in action.

In 1594, rumours that don Alonso, the cacique of the town of Fontibón, was determined to maintain various heterodox ritual practices among his community prompted another investigation by the Audiencia.Footnote 117 Led by the oidor Miguel de Ibarra, Audiencia officials arrived in the town searching for what they assumed were the pillars of Indigenous religion, priests and temples, but what they found was quite different. By the end of the sixteenth century, the idea that the Muisca were misled in religious matters by a self-perpetuating cohort of Indigenous priests was firmly established, and Ibarra’s report, as we have seen, compared the place they occupied among the Muisca to that of Christian bishops and archbishops, and went as far as to distinguish between different ranks of religious practitioners. Ibarra, for example, distinguished between ‘xeques and tibas, with xeques being the priests and tibas the sacristans’.Footnote 118 This focus by the colonial authorities on these perceived corrupters of the flock was common throughout the New World, and was rooted in biblical notions of false prophets. Whether or not they held the influence that was ascribed to them, they were repeatedly blamed for the persistence of non-Christian practices, and legislation was put in place to target them specifically.Footnote 119

The presence of Indigenous priests was so well established a trope that it was guaranteed to trigger a reaction from the authorities. In 1569, for example, the encomendero of Suba and Tuna, some ten miles north-west of Santafé, forwarded a complaint by a priest he had hired to provide instruction, Andrés de San Juan, to the Audiencia.Footnote 120 It described how the priest was struggling to hold his catechism classes and to impose his authority over local people, complaining that ‘all of this is caused by the xeques’.Footnote 121 Witnesses, all closely connected to the priest, described an entire hierarchy of Indigenous priests who were not only determined to sabotage his efforts, but who ran their own programme of counter-indoctrination with the cooperation of the Indigenous rulers of the town.Footnote 122 Their testimonies resemble a catalogue of the regime’s worst fears: heresiarchs, human sacrifice, murder, and intrigue. No evidence to prove these allegations was uncovered, but that hardly mattered. What was really going on was that most of the people of Suba and Tuna had refused to remain in the site of a new planned town to which they had been forced to resettle and had returned to their previous settlements, and the Audiencia had failed to do anything to stop it. The scandal served the priest and the encomendero to compel the authorities to take action to bring them back together.Footnote 123

In Fontibón in 1594, the authorities set about finding these individuals, but what they found shocked them: ‘as it turned out’, one of the officials later reported, ‘there were one hundred and thirty-five xeques’.Footnote 124 The numbers simply did not add up: even though Fontibón was then one of the largest encomiendas in the region, home to 507 tribute-paying men, these records suggested that over 20 per cent of the adult male population was a xeque.Footnote 125 Fontibón was not unique. The following year, an inquiry into non-Christian practices conducted in the more distant town of Iguaque, in the province of Tunja, offered a similar picture.Footnote 126 The town was much smaller, but the proceedings resulted in the prosecution of seven Indigenous authorities – caciques and captains – and fifteen others, here including women, for ‘having santuarios in the usage of their gentility’.Footnote 127 Rather than a specialised group of people devoted exclusively to religious functions, the picture that emerges suggests that these were simply individuals who held responsibility over certain ritual functions within their communities.Footnote 128 Above all, they were responsible for the maintenance of the santuarios. And here too things were not as the authorities expected.

The documentation of Iguaque and Fontibón, which has received the most scholarly attention, does not describe santuarios or the functions of these religious practitioners in detail, but a less studied report of that same year from Lenguazaque, a town in the same province, offers more.Footnote 129 The inquiry was launched when news reached the authorities that an Indigenous authority in town, Pedro Guyamuche, had used some gold from a hidden santuario to purchase some sheep and wheat from local Spaniards.Footnote 130 As a result, the visitor paid special attention to learning about them. He soon learned that ‘all captains have their santuarios’, but that they were not the only ones.Footnote 131 Other witnesses, including individuals who were not Indigenous authorities, also revealed that they had their own in their homes.Footnote 132 Eventually, officials came to a surprising realisation: santuarios were not buildings or places. Spaniards were asking for Indigenous temples, but Indigenous witnesses were instead producing portable objects. This became clearer to the visitor as the investigation progressed. He had initially referred to santuarios as places, such as when he accused Guyamuche of ‘having a santuario and idolising and adoring in it’, but he was soon asking about the materials out of which the santuarios were made: not bricks and mortar, but ‘cotton, or wood, or gold’.Footnote 133

This important insight shines new light into the well-thumbed records of Iguaque and Fontibón. There too, santuarios seemed to be everywhere, and were kept by people of all stations. In Iguaque, for example, while the authorities were concerned to find ‘the great sanctuary of this repartimiento’, they were instead presented with a variety of objects that made little sense to them.Footnote 134 In all cases, witnesses explained that they had inherited them through their families or close relations.Footnote 135 They were, most probably, lineage deities, and they bear some resemblance to the chancas of the central Andes – small portable objects often found in the dwellings of the individuals who inherited their care, and revered by their extended family or kinship group.Footnote 136

The people identified by Spaniards and prosecuted as xeques in these inquiries were largely the men and women who cared for these objects, who seemed to fulfil this function on behalf of their kinship groups. In Fontibón, for example, the authorities prosecuted 100 inhabitants of the town, who were listed in the documentation by their membership of each of the ten capitanías that composed the cacicazgo.Footnote 137 The catalogue resembles a list of each of the component subunits of each capitanía, of each of the matrilineal kinship groups that were the building blocks of the town, and it seems likely – as several scholars have proposed – that each kinship group included individuals responsible for maintaining its santuario and other sacred objects.Footnote 138

Santuarios performed a range of functions. Some were as basic as subsistence. In 1571, for example, Moniquirá, cacique of the community of the same name, complained to the Audiencia that one of his captains, Ucarica, had left the town and moved elsewhere with a number of his subjects. The cacique explained that the reason for his disappearance was that he had burnt the captain’s santuario, ‘which provided him with maize, potatoes, and mantas’.Footnote 139 In 1574, Indigenous witnesses in Tota explained that their cacique encouraged them to maintain their santuarios to secure the success of their crops, for the benefit of the entire community. One witness even reported how the cacique had explained that if the appropriate devotions were not performed for his santuario his subjects would not be able to harvest cotton.Footnote 140 At the same time, the santuarios were closely connected to the identity of the group, and to the maintenance of social and political hierarchies.

Nor were all santuarios equal. Some were clearly more exalted than others, in the same manner as the kinship groups with which they were associated were not equal. Caciques and some captains, for example, had dedicated staff and buildings for the maintenance of their particular santuarios, in a way that suggests that their positions of prestige and authority were connected to the resources and effort that they were able to employ in maintaining them on behalf of their communities. In Fontibón, cacique don Alonso was found to have four individuals to care for his santuario, with one holding it on his behalf.Footnote 141