The National Liberation Front (NLF), derogatorily called the Viet Cong by its enemies, was born in the mangrove swamps of Thanh Ninh province in South Vietnam on December 20, 1960. It was a classic front organization, founded by Vietnam’s Communist Party to harness the growing radical peasant movement in South Vietnam and to overthrow the South Vietnamese president, Ngô Đình Diệm, by force. Anyone, communist or noncommunist, could join the NLF as long as they shared the party’s goals. This was how united fronts, tactical organizations that mobilized all disaffected elements of society, had worked in Vietnam for decades. In practice, the NLF brought together trade union members, student associations, religious groups, political activists, lawyers and other professionals, and peasants, all in a temporary alliance to highlight political opposition to Saigon’s rule. Historically, these temporary alliances had helped the party achieve its objectives by putting enormous military and political pressure on the enemy, but they also neutralized potentially dangerous internal elements, especially among the intelligentsia.

To gain maximum advantage in the political war against Ngô Đình Diệm, the Communist Party carefully concealed its control of the NLF. The NLF purposefully created the impression that it was free and autonomous to exploit world opinion and frustrate the United States and its Saigon ally by making it impossible for them to build a cohort of supportive or at least sympathetic allies. By the mid-1960s, several world leaders and international organizations were convinced that the NLF was an independent actor in South Vietnam’s civil war. Postwar memoirs by some NLF members confirm this view. Trương Như Tảng, a founding member of the NLF, declared that he was never a communist and that it was Diệm’s repressive policies that had in fact contributed to the formation of the NLF by creating a groundswell of animosity throughout the country. That Tảng came from a privileged background provided even more evidence that Diệm’s policies were widely despised. According to the NLF’s own record, therefore, it had risen out of the tinder-dry paddy fields of South Vietnam in opposition to Diệm with little outside influence.

In sharp contrast, policymakers in Washington claimed that Hanoi alone directed the armed struggle in South Vietnam. Key members of the administration of John F. Kennedy argued that the flow of men and supplies from north to south kept the insurgency against South Vietnam alive. Stop this externally supported insurgency, they insisted, and South Vietnam could stand on its own. Almost all of the official policy papers released by the Kennedy administration on the insurgency in South Vietnam used the same title: “A Threat to Peace: North Vietnam’s Effort to Conquer South Vietnam,” which provided a rationale and justification for American intervention. According to the document’s several authors, the NLF was nothing more than a puppet on a string. They argued that communists in Hanoi had gone to great lengths to conceal their direct participation in the program to conquer and absorb South Vietnam.Footnote 1 Kennedy officials claimed that North Vietnam had violated the spirit of the Geneva Agreement of 1954, which had temporarily divided the country at the 17th parallel, by launching an insurgency against South Vietnam. Because of Hanoi’s actions, Diệm had the right to ask for and receive US military aid and assistance. This aid would be used by the Saigon government to launch a massive counterinsurgency program against the NLF.

These official interpretations put forward in Washington policy papers clouded the complex nature of the NLF, however, making it more difficult to create an appropriate response. Kennedy administration officials often overlooked the fact that Vietnam’s Communist Party was unified and nationwide. Kennedy’s team also purposefully downplayed the widespread opposition to Diệm. These problems were magnified by the unfortunate choice by US policymakers to call anyone connected to the Communist Party’s leadership “North Vietnamese.” Kennedy’s analysts did, however, correctly stress the role of the party in creating the NLF. But deciding that the NLF was both Southern and communist, and that it had broad-based support from noncommunists, was something that the Kennedy administration was not prepared to do.

Critics of American intervention in Vietnam have long argued that the insurgency in South Vietnam was essentially a civil war and that the NLF was free and independent of the Communist Party. Antiwar scholars and activists suggested that the NLF had risen at Southern initiative in response to Southern demands. The French historian Philippe Devillers, a long-time student of Vietnam, declared that people living in South Vietnam were literally driven by Diệm to take up arms in self-defense. He argued that the insurgency had existed long before the communists decided to take part, and that Hanoi was forced to organize the NLF or risk losing control of the radical peasant movement.Footnote 2 In this telling of the founding of the Front, it was Diệm’s own repressive policies, such as Law 10/59, which allowed for arrest of suspected communists without formal charges, that had forced Southerners to take action. Devillers was joined by another Vietnam expert, Jean Lacouture, who claimed that “the actual birth of the National Liberation Front must be traced back to March 1960. At that time a group of old resistance fighters assembled in Zone D (South Vietnam), issued a proclamation calling the prevailing situation ‘intolerable’ for the people as a result of Diệm’s actions, and called upon patriots to regroup with a view toward ultimate collective action.”Footnote 3 Devillers, Lacouture, and many other antiwar scholars may have overstated the independence of cadres in South Vietnam in their relations with the Communist Party and its Central Committee, but they did understand that Diệm was pushing many people into the NLF fold.

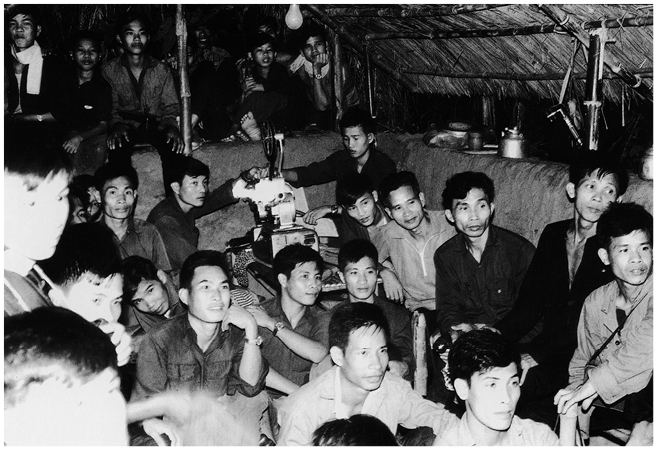

Figure 8.1 National Liberation Front soldiers watching a film in Củ Chi, South Vietnam (1972).

In short, the NLF was both Southern and controlled by the Communist Party. This gave the NLF a distinctly Southern worldview, but it also meant that the Front adhered to party diktats from the Central Committee in Hanoi. This often led to tension within the party, as those who favored building socialism in the North clashed over tactics and strategy with those within the party who favored increasing support for the Southern revolution. This tension was a key feature of the inner workings in the corridors of power in Hanoi and sometimes resulted in dramatic actions against those who disagreed with the party’s primary stakeholders, like Lê Duẩn, its future secretary general, and Lê Đức Thọ, a member of the party’s Politburo.

The Direction of the Revolution

These tensions existed before the NLF’s formation and led to an intense five-year debate over the future of Southern revolution. From the division of Vietnam at the 17th parallel in 1954, party leaders struggled to balance its competing revolutionary goals. Throughout the newly created South Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm’s national security police had been particularly effective in destroying party cells, and by 1957 cadre levels had fallen off dramatically. Diệm’s success against party cells forced the debate in Hanoi. Many party leaders wanted to continue trying to liberate South Vietnam by political means alone, following the Soviet Union’s model put forward at Moscow’s 20th Party Congress in 1956, when Premier Nikita Khrushchev denounced Joseph Stalin and outlined a policy of peaceful coexistence with the West. Khrushchev announced that the transition from capitalism to socialism could be peaceful if parliamentary means were applied adequately. In Vietnam, this meant that the party would try to build up socialism in the North while using political measures to overthrow Diệm, like the scheduled elections following the protocols of the Geneva Accords.

Many Southern leaders within the party, especially Lê Duẩn, the secretary of the Nam Bộ Regional Committee – the party’s southern-most organizational structure – thought that the Central Committee was being too cautious. He argued that the only way to build up cadre levels and overthrow Ngô Đình Diệm was through armed violence. With Lê Duẩn at the helm, the Nam Bộ Regional Committee concluded:

Due to the needs of the revolutionary movement in the South, to a certain extent it is necessary to have self-defense and armed propaganda forces in order to support the political struggle and eventually use those armed forces to carry out a revolution to overthrow US–Diệm … the path of advance of the revolution in the South is to use a violent general uprising to win political power.Footnote 4

One of Hanoi’s official histories of the war claimed that Lê Duẩn had effectively tipped the balance within the party in favor of a greater commitment to the revolutionary movement in the South through sheer force of will and a dogged determination to see the revolution enter its next phase. It concluded that “At the end of 1956 the popularization of the volume by Comrade Duẩn entitled ‘The South Vietnam Revolutionary Path’ [Đường lối cách mạng miền Nam, c. 1956] was of great significance because the ideological crisis was now solved.”Footnote 5

Lê Duẩn also drafted a number of important policy guidelines that shifted the party’s priority from building socialism in the North to armed resistance against Diệm, including his crucial report to the party at its 15th Plenum in January 1959, convincing it to form the NLF. By the time of the party’s 3rd National Congress in September 1960, Lê Duẩn’s power and influence were clear; he replaced Trường Chinh as the party’s secretary general, the most important leadership position in Hanoi. With Lê Duẩn at the helm, Vietnam’s Communist Party dramatically increased the tempo of revolutionary activity in the South, beginning with the founding of the NLF in December 1960. The birth of the NLF, therefore, signaled the Communist Party’s willingness to move to revolutionary violence to liberate South Vietnam and reunify the country. By giving the green light to armed rebellion, the party sought to capture and control the growing radical peasant movement inside South Vietnam and to harness middle-class resentment against Diệm on the part of students and professionals. The party also sought out sympathetic Catholics and Buddhists, who opposed Diệm, but who may not have supported the party’s long-term objectives. Party leaders hoped that the NLF and its military wing, the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF), could topple the Saigon government before the United States enlarged and escalated the war. Failure to achieve this goal meant that the NLF/PLAF and its allies in North Vietnam had to endure years of fighting and bombing to finally take Saigon by force in 1975.

Launching the Revolution

Once the NLF was formed, the level of violence in South Vietnam increased dramatically. By late 1961, US intelligence estimated that the PLAF’s main forces numbered nearly 17,000. These troop levels were to grow to 23,000 in 1962, 25,000 in 1963, and 34,000 by late 1964. The NLF also controlled some 72,000 village self-defense and regional defense forces. By January 1964, the party’s Central Office in South Vietnam, COSVN, claimed it had 140,000 total armed forces at its disposal along with People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN, or North Vietnamese army) troops who had infiltrated into South Vietnam. During these early days of the PLAF, its units were platoon-sized and took orders from party committees at the district and province levels. There was little command and control within the PLAF at this time, making it nearly impossible for its revolutionary forces to do much more than mount quick strikes on isolated South Vietnamese outposts and provide security for party cadres. By the end of 1962, however, three main-force PLAF regiments came together in the Central Highlands, ushering in the process of independent platoons and companies coming together into larger units. This process continued to unfold throughout the war.

The NLF buildup convinced the Kennedy administration that Diệm now faced an active insurgency and that Saigon was in a battle for its very survival. At every turn, the NLF seemed to score significant victories against Diệm, forcing Washington policymakers to dramatically increase the US level of support for South Vietnam. In a program called Project BEEF-UP, the Kennedy administration doubled its military assistance to the Saigon government from 1961 to 1962 and tripled the number of American advisors to the Army of the Republic of South Vietnam (ARVN, or South Vietnamese army). The intensified US effort was brought under the control of a new command structure, the Military Assistance Command–Vietnam (MACV). The goal was to halt the NLF’s progress in the countryside and give Diệm’s counterinsurgency programs and US political and economic aid a chance to take a foothold in South Vietnam. Success against the NLF remained elusive, however, so some of Kennedy’s advisors argued that the president had to approve sending US combat troops to South Vietnam in order to save Diệm’s government.

Kennedy rejected the call for US troops – as did Diệm – and instead increased the counterinsurgency effort against the NLF. On November 30, 1961, Kennedy also approved the use of defoliants and herbicides to defoliate the jungle in NLF-controlled territory. Initially, Kennedy held tight control over the spraying program, but by late 1962 Diệm had convinced the US president to relinquish control to the US mission in Saigon, allowing for more liberal spraying against NLF strongholds. Thus began Operation Ranch Hand, which from 1962 through 1971 would spray more than 19 million gallons of defoliants over South Vietnam.

Along with the military buildup, Kennedy also endorsed a political and economic program to help stabilize the Saigon government and thwart the NLF’s effort. Kennedy’s advisers pressed Diệm to make meaningful political reforms, such as loosening the reins on the military and secret police, hoping that democratic reforms might win back the middle class. When Diệm refused, the noncommunists in the NLF became even more enraged. Not only did Diệm have to deal with a counterinsurgency in the countryside, but his refusal to bend politically meant that he also had to confront urban unrest in South Vietnam’s major cities. Of course, all of this was front-page news as the international press swarmed Saigon to cover the war. The party grew quite skillful at exploiting Diệm’s weaknesses on the political front.

Diệm thought he could quiet his domestic opponents and resist American calls for reform by scoring significant military victories. By the summer of 1962, the South Vietnamese armed forces claimed a number of successes that improved the mood in Saigon and Washington and bought Diệm some respite from the Kennedy administration’s criticisms. The ARVN, paired with US helicopters, enjoyed some success against the PLAF in the Mekong Delta and northwest of Saigon. The ARVN offensives were aimed at key villages that seemed to be NLF strongholds. Coupled with these military operations against the NLF, Diệm’s government also introduced the Strategic Hamlet Program, designed to mobilize peasants into active support of the government through a redistributive land reform program and self-defense. NLF leaders acknowledged that the program enlarged key areas under Saigon’s control and interfered with their cadres’ access to the rural population of South Vietnam. The ultimate objective, as Kennedy’s advisor Roger Hilsman suggested, was to reduce the NLF to a “hungry, marauding band of outlaws devoting all of their energies to staying alive” and to force the communists out into the open where the ARVN could destroy them.Footnote 6 For a short time, the Strategic Hamlet Program did stabilize the situation in South Vietnam. Buoyed by the good news from South Vietnam, Kennedy even instructed his secretary of defense, Robert S. McNamara, to draw up plans to redeploy 1,000 US military advisors elsewhere. This move was born out of Kennedy’s optimism that Diệm was gaining ground against the communists, not out of his desire to withdraw from Vietnam altogether.

Kennedy’s optimism quickly gave way to pessimism, however, as the ARVN suffered an apparent setback against the PLAF in early 1963. At Ấp Bắc, a tiny hamlet in Mỹ Tho province eighty kilometers south of Saigon, about 2,000 troops from the ARVN’s 7th Division encountered 300–400 well-entrenched PLAF regulars. Caught in an ambush by the waiting communist troops, the ARVN called in helicopters, armed personnel carriers, and US advisors to assist in the battle. The PLAF shot down five helicopters and reportedly inflicted 190 casualties on the ARVN while it claimed to have escaped with only 12 combat deaths (the number was probably significantly higher). Despite the fact that the ARVN had actually acquitted itself quite well and eventually secured Ấp Bắc as the PLAF withdrew, US advisors could not help but conclude that the ARVN was no match for the communists. Lieutenant Colonel John Paul Vann, a key ARVN advisor, called the battle a “damned miserable performance.” Another American advisor went even further, claiming that “Time after time I have seen the same Vietnamese officers and troops make the same mistakes in virtually the same rice paddy.”Footnote 7 The US Defense Intelligence Agency concluded that the ARVN had made little progress in its war against the PLAF, despite enjoying numerical superiority.

The US press declared that Ấp Bắc was “a major defeat” in which “communist guerrillas shot up a fleet of United States helicopters carrying Vietnamese troops into battle.”Footnote 8 The Washington Post printed Neil Sheehan’s firsthand account of Ấp Bắc on its front page. Sheehan wrote that “angry United States military advisers charged today that Vietnamese infantrymen refused direct orders to advance during Wednesday’s battle at Ấp Bắc and that an American Army captain was killed while out front pleading with them to attack.”Footnote 9 Top US military leaders, including General Paul Harkins, the MACV commander, feared that Kennedy was not getting a complete picture of the battle of Ấp Bắc or the ARVN’s counterinsurgency program against the NLF. Harkins warned the president that it was “important to realize that bad news about American casualties filed immediately by young reporters representing the wire services” did not represent the true facts about Ấp Bắc. He also concluded that “it hurts here when irresponsible newsmen spread the word to the American public that GVN [South Vietnamese] forces won’t fight and, on the other hand, do not adequately report GVN victories which are occurring more frequently.”Footnote 10 While the debate over what really happened at Ấp Bắc raged on in Saigon and Washington, the NLF celebrated its windfall by launching more ambushes against the ARVN in the Mekong Delta and increasing its membership dramatically. It appears Sheehan was right.

The NLF’s leadership also scored some significant diplomatic victories during the Diệm–Kennedy years. The Front created a foreign relations commission that sent diplomats to Europe, to North America, and to many nonaligned nations to convince world leaders that the NLF wanted a coalition government in Saigon. The NLF’s top diplomat, Nguyễn Vӑn Hiếu, declared that the NLF was willing to engage in negotiations with the Saigon government to produce a “peace-loving and democratic government.”Footnote 11 Few in the party expected the Kennedy administration or the Diệm government to accept the call for a coalition government, but it did put international pressure on Diệm to launch reforms to make South Vietnam more just and inclusive. The NLF turned up the diplomatic heat when Diệm’s brother, Ngô Đình Nhu, used his secret police to raid Buddhist temples to rid them of suspected communists throughout the summer of 1963. The crisis was a public relations nightmare for Kennedy, who hinted that Diệm needed to make drastic reforms if he wanted to continue to receive US aid. The crisis came to a head in the summer of 1963, when Nhu wondered out loud if the United States knew what it was doing in Vietnam and then opposed the further expansion in the number of American advisors.

The NLF took advantage of the crisis by reaching out to Nhu to see if he might be interested in negotiating an all-Vietnamese solution to the conflict in South Vietnam. The not-so-secret contacts infuriated the Kennedy administration, though it is likely that the NLF understood the limits of the back channel. Nhu hoped to use the contact with the NLF to loosen the US grip and save his brother’s government, but Kennedy was unmoved. The administration was aware that French president Charles de Gaulle had also tried to open secret contacts between Nhu and the communists. On September 15, 1963, de Gaulle had instructed the French ambassador in Saigon to promote the idea of a coalition government between the NLF and Diệm. The ambassador, Roger Lalouette, contacted the Polish representative to the International Control Commission, Mieczyslaw Maneli, who approached the communists and Nhu on the possibilities of a real bargain. Maneli felt encouraged by his first contact and pursued the matter until Diệm and Nhu were assassinated by their own officers on November 1, 1963. President Kennedy was assassinated three weeks later.

The NLF at War

Lê Duẩn hoped to capitalize on the chaos and confusion in Saigon following Diệm and Nhu’s assassination by ushering in a new phase of the war that would rest heavily upon the NLF’s ability to launch a general offensive and general uprising. The goal was to launch military offensives in the countryside combined with political uprisings in the cities of South Vietnam to secure a victory against Saigon in 1964. Lê Duẩn was convinced that the Saigon government was sitting on a powder keg that was ready to explode. At the party’s 9th Plenum in December 1963, Lê Duẩn led a movement to commit the revolution to a bigger war in South Vietnam by ushering in a major buildup of conventional forces. There was some opposition in Hanoi to throwing all of the party’s resources behind the war in South Vietnam, but Lê Duẩn carried the day and eventually the Hanoi leadership approved the measure in order to bring the war to a quick conclusion. The new resolution approved sending PAVN main-force infantry units to the Central Highlands and northwest of Saigon and to dramatically increase supply traffic along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail.

This military buildup of PAVN troops inside South Vietnam caused some consternation in Hanoi among those who were devoted to building socialism in North Vietnam, but it also brought the ire of many NLF revolutionaries who complained that building up PAVN conventional forces operating in South Vietnam went against their strategy to win peasants and South Vietnam’s middle class to the revolution’s cause. They suggested that sending a PAVN division to South Vietnam (in this case elements of the 325th), and therefore shifting military operations away from guerrilla tactics, was foolhardy. The NLF victory at Ấp Bắc and its success in building political opposition to the Saigon government was reason enough, NLF leaders concluded, to stick with its guerrilla strategy. Some NLF leaders suggested that such large-scale warfare was not simply premature, but unnecessary. The debate ended with the resolution at the 9th Plenum. Lê Duẩn then named PAVN general Nguyễn Chí Thanh the director of COSVN to oversee the PAVN military buildup. General Thanh quickly moved the revolution’s military footing to a more conventional war strategy, resulting in the first big engagement with US troops at the battle of Ia Đrӑng Valley in November 1965.

While the PAVN joined the fighting inside South Vietnam, the NLF launched an urban movement that played a major role in the revolution’s effort to prevent US entry into the war or, more precisely, to prevent Kennedy’s counterinsurgency war from turning into President Lyndon B. Johnson’s ground war. Beginning in April 1964, the NLF’s revolutionary forces established working control of the majority of legal and semi-legal organizations in and around Saigon. The NLF used the General Student Union and the Representatives of High Schools, for example, to highlight the depth of antiwar sentiment among South Vietnam’s young people. The Ấn Quang Buddhist movement also used party-approved slogans to voice its displeasure with the war and to challenge the Saigon government’s legitimacy. Urban intellectuals and Catholic-supported peace organizations also joined the NLF’s calls for the ouster of the Saigon government and the formation of a coalition government. These urban intellectuals were the backbone of the NLF’s urban movement from 1964 until the 1968 Tet Offensive, when Hanoi decided to push aside middle-class students and professionals to embrace the idea, instead, that only a violent military victory could complete the revolution. Lê Duẩn is reported to have claimed that the Saigon government was violent from beginning to end and that the revolution must therefore be violent. He also believed that victory would come from a general offensive and general uprising: “Tổng công kích, Tổng khởi nghĩa.”

Hanoi’s planning for the 1968 Tet Offensive remains shrouded in mystery, but some analysts have suggested that many NLF leaders may have objected to the party’s go-for-broke strategy, fearing that it was premature to think about a massive, urban uprising ignited by military attacks throughout South Vietnam.Footnote 12 The war in South Vietnam had ground to a stalemate despite massive PAVN infiltration and increasing numbers of American troops. There was no end in sight to the spiral of escalation, and so some NLF officials worried that a premature general offensive would expose some of the revolution’s weaknesses.

Following Diệm’s assassination, the NLF’s army – the People’s Liberation Armed Forces – spent much of their time at remote bases training and gathering supplies for future battles against the ARVN and the influx of American troops. When they ventured out, it was often in small detachments to aid the political–military struggle in the countryside. Two of the key goals of the NLF in this infantry phase of the war were to bolster the authority of local communist cells and to attack government-controlled hamlets and outposts. The PLAF rarely operated beyond company strength and tried to preserve its force structure by limiting its attacks against its enemies. In the few set-piece battles that did take place in the Central Highlands and north of Saigon near the Cambodian border, the NLF saw its army take heavy losses. The war was quickly reaching a military stalemate, and some leaders in Hanoi blamed the NLF for the need to have the PAVN take on more of the fighting.

Still, Lê Duẩn and Lê Đức Thọ convinced their fellow Politburo members that the time was ripe for a major military move to break the stalemate and force the United States to negotiate the terms of its own withdrawal from South Vietnam. But not everyone agreed with this strategy. General Võ Nguyên Giáp, a senior PAVN leader and the hero of the Điện Biên Phủ victory of 1954, charged that the offensive was premature and would not bring about a quick military victory. He joined Hồ Chí Minh in opposing the idea of a grand offensive when it was first discussed in Hanoi in 1967. Over time, however, Giáp eventually relented, agreeing that a general uprising might be successful if PAVN troops could first cripple the ARVN in big-unit warfare. Lê Duẩn and PAVN general Vӑn Tiến Dũng played a significant role in helping Giáp change his mind. With Giáp on board, plans moved forward in Hanoi to launch a general uprising with PAVN and PLAF troops, hoping to remove Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu from power in Saigon.

On January 30, 1968, combined PAVN and PLAF troops launched a coordinated attack against the major urban areas of South Vietnam. While the PLAF led the urban attacks, the PAVN focused on US bases in the Central Highlands. None of these attacks was more dramatic than what happened at the US Embassy in Saigon. At 2:45 a.m., a team of PLAF sappers blasted a large hole in the wall surrounding the embassy and entered the courtyard inside the gates. For the next six hours, the PLAF sappers battled a small detachment of ARVN and US military police. By 9:00 a.m., all of the PLAF troops had been either killed or captured. Though the PLAF was rather quickly overpowered, the image of the US Embassy under attack cast doubt on American claims that the end of the war was in sight. Some reporters editorialized that the war was going badly and that the American public had been lied to by its leaders.

The American public grew even more restive when Nguyễn Ngọc Loan, the chief of the South Vietnamese National Police, was captured on camera executing a suspected NLF assassin on the streets of Saigon. Eddie Adams won a Pulitzer Prize for his now-iconic photograph showing the moment that the bullet flew into Nguyễn Vӑn Liêm’s head. Liêm, also known to his NLF cadres as Bay Lop, was in charge of a small PLAF assassination squad that targeted members of Saigon’s National Police and their families. Many South Vietnamese officials believed that he had been responsible for the deaths of seven police officers and a handful of their family members during the first days of the Tet Offensive. This was Loan’s rationale and justification for shooting Liêm without the benefit of a trial. No matter the circumstances, the street execution caused an angry outcry from the US public. American public opinion against the war seemed to be increasing along with Saigon’s problems. Winning this psychological war marked the high point of the Tet Offensive for the NLF.

The NLF’s low point, however, came during the second and third phases of the Tet Offensive. The initial planning for the offensive included attacks against the urban areas of South Vietnam throughout the summer of 1968. During the second phase, the PLAF focused its effort on Saigon. The fighting was fierce, and in the end the revolution had managed to destroy much of the city’s infrastructure in its southernmost reaches along the river. However, the NLF experienced unusually high casualties and its offensive failed to produce a general uprising of Saigon’s population against the government. Lê Duẩn hoped that the third phase, scheduled for late August through September, was perfectly timed with the US election to force the Johnson administration to negotiate an end to the war in Paris. Yet again the offensive stalled, however, leading to high PLAF casualties. During this last phase, American B-52 bombers supplied enough air cover for the ARVN to counterattack effectively. By late October, it was clear that Lê Duẩn’s desire for a speedy end to the war was not going to be realized and that the PLAF had suffered significant losses during the Tet Offensive.

For example, in the Mekong Delta city of Mỹ Tho, the PLAF suffered shocking losses. The PLAF had managed to launch an attack inside the city’s borders with eight divisions, but those troops were confused by the urban terrain and were unable to converge on their targets. They were forced to retreat when US and ARVN artillery easily targeted their movements. In the process, the heavy bombing destroyed five thousand residences and forced nearly a third of the city’s population to abandon their homes. The PLAF’s main-force units suffered casualty rates of 60 to 70 percent, and losses among revolutionary cadres may have been even higher. Such huge losses meant that the NLF had to abandon some areas in South Vietnam it had previously held easily and that it became more reliant on the PAVN.

Those losses were magnified by the accelerated pacification program aimed at the NLF’s infrastructure. Beginning in 1969, Saigon’s effort to extend its control of the countryside entered a new phase, the direct attack against what was known as the VCI, the Viet Cong Infrastructure. This effort was known as the Phoenix Program, which grew out of Operation Recovery, an intense MACV and Saigon government program to reclaim territory lost to the revolution during the Tet Offensive. The Phoenix Program used Provincial Reconnaissance Units to identify and arrest or kill key NLF leaders. Phoenix quickly gained the reputation as an assassination program, eventually forcing the MACV and the US Central Intelligence Agency to withdraw its support. Saigon continued, however, and claimed to have neutralized nearly 70,000 VCI. Though these numbers may be accurate, it appears that very few of the NLF’s top leaders were caught in the Phoenix trap. Still, Phoenix created enormous difficulties for the NLF immediately following the Tet Offensive.

One unanticipated outcome of Tet, Operation Recovery, and the Phoenix Program was that the indiscriminate violence in the countryside forced many of South Vietnam’s peasants to flee to the relative safety of urban areas. The forced urbanization of millions of Vietnamese peasants – what political scientist Samuel Huntington aptly described as forced draft urbanization, an artificial urbanization caused by war in the countrysideFootnote 13 – disrupted even the most elementary sociopolitical patterns that had developed in Southern villages since the mid-nineteenth century. It was difficult for villagers to remain villagers as war and socioeconomic dislocation threatened their very existence. As the war escalated, millions of peasants became refugees, fleeing to nearby provincial cities for safety and security. The NLF hoped to capture the loyalties of these urban refugees, but so too did the Saigon government. Government officials in Saigon hoped that, once peasants had fled to the cities, the former villagers could be easily controlled as they became dependent on government resources for their very survival. This dependency relieved Saigon of the responsibility for motivating and mobilizing the rural population, which South Vietnamese politicians sometimes struggled with in any case. It also meant that the government could counteract any NLF efforts to mobilize these urban refugees to the revolution’s cause. The battle for the hearts and minds of Vietnamese peasants had become an urban affair following the Tet Offensive and the devastation caused by the Phoenix Program.

Following the Tet Offensive, the party also decided that it needed to elevate the status of the NLF by proclaiming the establishment of the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG). Founded on June 6, 1969, the PRG superseded the NLF in most political and diplomatic functions, particularly the secret negotiations taking place in Paris. The PRG named Nguyễn Thị Bình its minister of foreign affairs, and she became its lead negotiator with the Americans in the Paris Peace Talks. She also replaced Hồ Chí Minh, who died in September 1969, as the symbol of the revolution, or at least she was touted as such by the party. She traveled extensively throughout Europe during breaks in the Paris negotiations, promoting the idea of the PRG as the government-in-waiting in South Vietnam. Her considerable intellect, ease with foreigners, and English-language skills made her a natural spokesperson for Southern dreams and aspirations.

Conclusion

During the war with the Americans, many Southerners believed that reunification between North Vietnam and South Vietnam would come as the result of negotiations between the NLF and the Communist Party. This assumption had been the rallying point for many noncommunists in the NLF and had helped create the political crisis that led to military victory over the Saigon government. Reunification came swiftly, however, and the NLF and the PRG were relegated to the sidelines. The NLF was born in December 1960, and the party ended it in May 1975. It was a classic communist front organized to achieve specific goals and, once those goals were met, it was quickly dismantled and its noncommunist members were tossed aside, or worse. But the NLF played a vital role in Saigon’s defeat, and few in the party could challenge that claim. Eventually, former NLF members rose through the ranks of power in Hanoi. The history remains contested, and the role of the NLF in Vietnam’s modern revolution is still controversial.