Introduction

This chapter examines the French Indochina War in the Central Highlands. Instead of focusing exclusively on military strategies and operations between 1945 and 1954, I explore the changing relations and mutual perceptions among the main protagonists in the conflict: indigenous Central Highlanders, the Việt Minh, noncommunist Vietnamese, French, and Americans.Footnote 1 During both the war of 1945–54 and in the subsequent “Vietnam War,” the importance of the Central Highlands lay in the region’s strategic position relative to the more populated surrounding areas. As Việt Minh General Võ Nguyên Giáp is alleged to have remarked, “To seize and control the highlands is to solve the problem of South Vietnam.”Footnote 2

Decades before the war began, French colonial authorities recognized the strategic importance of the Central Highlands. In hopes of strengthening their control over the region, they developed policies to promote a single ethnic identity among Highlanders – one that was putatively incompatible with the culture and political projects of lowland groups, especially ethnic Việt (Kinh). During the French Indochina War, French colonialism, Vietnamese nationalism and communism, and nascent American imperialism nurtured diverging plans for the region, each predicated on different views of sovereign authority. These competing claims to sovereignty over the Central Highlands collided violently in the second half of the 1940s. Highlanders responded to the violence by siding with one or the other party, by shifting sides, or by not taking sides; while some took up arms or engaged in other acts of resistance, others found themselves the target of military operations or coercive policies such as forced resettlement.

The Central Highlands are a mountainous region in what is now south-central Vietnam, bordered by the Annam Cordillera (Trường Sơn) to the north, a narrow coastal strip and the South China Sea to the east, the Mekong Delta to the south, and Laos and Cambodia to the west. In the 1940s the Highlands were thinly populated by a wide array of different ethnolinguistic groups, speaking different languages and dialects and adhering to different customs. They lived scattered in villages, sustaining themselves via shifting agriculture, hunting, gathering, and trade, and rarely developed durable “tribal” organizations beyond the village. Relatively few lowland Việt, Lào, Khmer, and Chӑm lived among the Highlanders or in the Highlands and those who did resided mostly in the towns of Kontum, Dalat, Banméthuot, and Pleiku.

Although the region was deemed strategically important, it was not well known. Ethnonyms and toponyms have changed frequently over the decades and many of the terms and labels used during the war are currently deemed offensive. These include words like mọi (moï/moy), a Vietnamese term denoting “savage,” and having servile connotations related to the slave trade; Montagnard, a French colonial designation for Highlander; Annamite, a French term for ethnic Việt; and coolie, a term referring to laborers and plantation workers.Footnote 3 In French, the Central Highlands were alternatively known as Pays moï, Hauts plateaux du centre, or Pays montagnard du sud-Indochinois (PMSI). In contemporary Vietnamese the region is designated as Tây Nguyên (literally meaning Western Highlands), while the former Republic of Vietnam (RVN) called it Cao Nguyên (High Plateau) or Trung Nguyên (Central Plateau). In this essay, I will invoke these terms not in the name of verisimilitude, but as a means to unpack the agendas that lay behind them. In the Central Highlands, as in other regions of Indochina, the power to name people, places, and communities was intimately linked to claims about legitimacy and sovereignty (Figure 9.1).

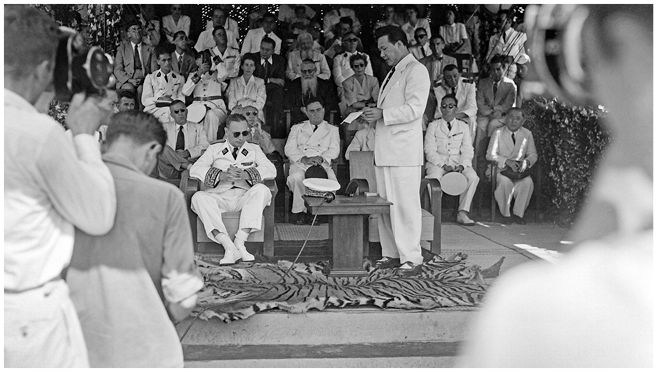

Figure 9.1 Bảo Đại, emperor of Annam, and ethnic minority leaders in Indochina (c. 1930s).

Legacies of Divide-and-Rule

During the first half of the twentieth century, a series of French colonial policies deeply impacted the discursive “ethnoscape”Footnote 4 of the Central Highlands and adjacent areas. These strategies included tribalization (turning loosely interconnected population groups into “tribes”), ethnicization (unifying these distinct “tribes” under a single ethnic label), and territorialization (tying Highlander populations to specific territories through state policies).Footnote 5 The combined results of these processes was an emerging common Highlander identity linked to a carefully demarcated territory.

These intertwined policies can be traced back to Léopold Sabatier (1877–1936), administrator of the highland province of Darlac from 1911 to 1926. Sabatier sought to protect “his” Rhadé tribe against the “double threat” of Việt settlement and French colonization in the form of rubber, coffee, and tea plantations. Although forced to step down in 1926, his measures sparked a debate among French officials and colonists about the desirability of settler colonization in the Highlands. At the height of the debate in the mid-1920s, the military command of French Indochina commissioned Lieutenant-Colonel Ardant du Picq to assess the strategic significance of the Central Highlands in case of a foreign attack or a revolt in the Vietnamese lowlands. The study aimed to examine “the Administration and the indigenous policy which dominate the military question and give it, in the moy country, a particular aspect.”Footnote 6 More than two decades before the outbreak of the Indochina War, Ardant du Picq emphasized the martial qualities of the Highlanders and argued that the colonial administration should seek to gain their confidence – a position that militated against settler colonization. But in the boom years of the 1920s, economic interests prevailed over military concerns, leading to massive land appropriation and forced labor recruitment for plantations.

French colonial rule of the Highlands was predicated on the separation of distinct “tribes,” classified according to language and territory. In this way, “tribal” identities and boundaries were constantly (re)constructed and solidified through the development and teaching of vernacular scripts and governance through customary law, resulting in a process baptized tribalization by Georges Condominas. This process was symbolized by the semiofficial ethnographic map of the Société des études indochinoises of 1937.Footnote 7 “Pacified tribes” such as the Rhadé were subjected to dispossession while the “rebellious tribes” (tribus insoumises) were targeted in “penetration” campaigns. In the 1930s, however, this ongoing colonial encroachment led to revolts under N’Trang Lơng among the Mnong and Kommadam among the Boloven. From 1936–8 a millenarian movement led by Sam Bram swept all the different “tribes” in the Central Highlands, undermining the notion of insurmountable tribal divisions.Footnote 8

These developments triggered two official responses. In 1935, military officers posited the desirability of the “creation of an autonomous Moï territory directly under the Governor-General,” to be administered by military officers. Although this proposal was rejected by the civil authorities, it would gain new momentum during the following decade.Footnote 9 Around the same time, Maurice Graffeuil, résident-supérieur of Annam, decided to reorient indigenous administration toward a “Moï hierarchy” directly under the French resident, without a parallel “Annamese mandarinate” – thus enshrining ethnic separatism into policy.Footnote 10 Subsequent measures included codification of Montagnard customary law for reasons of policing and administration, and the transcription of Montagnard languages for educational policies at the expense of teaching Vietnamese.Footnote 11

The emergence of the leftwing Front Populaire in France (1936–7) instigated additional changes. A “Committee of Investigation on the Overseas Territories” proposed to replace the “old divide-and-rule formula” with a “policy of domestication” (politique d’apprivoisement). This ostensibly more humane approach combined seduction with coercion. The state offered Highlanders medical services such as campaigns to eliminate smallpox and malaria, along with education in vernacular languages; yet it also promulgated its so-called “salt policy” (politique du sel) to control the sale and distribution of this vital commodity. Officials also increased the number of Montagnard recruits for the Bataillon des tirailleurs montagnards du Sud-Annam (BTMSA) from 1938 onward.Footnote 12 The pays moï, as the Highlands were now called, became the object of policies to promote “the vigilant protection of the natural qualities of the Moï races” for both humane and strategic reasons. In July 1938, Governor-General Jules Brévié decided that the Moï – despite the many differences among its component communities – constituted one “racial group,” distinct from all other Indochinese “races.” This ethnicization was formalized in October 1939, when senior officials inaugurated the Inspection générale des pays moïs. In this way, colonial governance formally classified Central Highlanders as “tribes” linked to particular locales in a process of territorialization. At the same time, Highlanders were practically removed from the Vietnamese administration that governed the “protectorate” of Annam.

The arrival of Japanese imperial forces in Indochina during 1940–1 directly impacted French designs in the Highlands. Despite leaving the French administrative infrastructure intact, the Japanese military command obstructed the complete territorial detachment of the Pays moï from Annam. Moreover, the Japanese posed as protectors of Vietnamese sovereignty to appease conservative nationalists, who criticized French separatist policies. Meanwhile, in 1941, the Indochinese Communist Party under Hồ Chí Minh established the Việt Minh as a broad anticolonial and antifascist coalition. Operating from bases in northern Vietnam, communist cadres hooked up with “tribal” resistance fighters in the mountain districts of Quảng Ngãi, Quảng Nam, and Quảng Trị provinces in central Vietnam. As early as 1940–1, the French Sûreté reported the activities of communist cadres such as Trần Miên among the “Moï Khaleu” (Bru) in upland Quảng Trị.Footnote 13 Vietnamese communist historians now trace a direct line from this tribal resistance movement to the “revolt of Ba Tơ” in upland Quảng Ngãi (1945), which continued a localized rebel tradition.Footnote 14

An interesting footnote in this wartime history is a never-implemented plan of the United States’ Office of Strategic Services to conquer Indochina by dropping commandos in the Central Highlands and inciting revolt against the Franco-Japanese regime.Footnote 15 Engineered by Hungarian-born and French-trained anthropologist Georges Devereux (György Dobó, 1908–85) together with Commodore Milton E. Miles, the “Special Military Plan for Indochina” envisaged the utilization of the Montagnards for guerrilla warfare against the Japanese, guided by a group of twenty unconventional warfare experts headed by Devereux. Miles and Devereux proposed to insert the group near Kontum, where Devereux had done fieldwork among the Sedang in the early 1930s. The plan was to hold some 3,800 square miles (10,000 square kilometers) of jungle and recruit a minimum of 20,000 men in the hinterland of Annam. Devereux was confident he could rally the Sedang and other groups because “the natives hate the French as bitterly as they hate the yellow races.”Footnote 16 But Devereux did not inspire much confidence among his peers (who viewed him as a “nutter”) and in July 1943 he was relieved of his command. While his plan was never implemented, it anticipated later US efforts to mobilize and recruit Highlanders to fight in anticommunist militias during the 1960s.Footnote 17

French wartime policies would become the model for their post–1945 attempts to reconquer and govern the Central Highlands. Colonial officials aimed to woo Highlander populations by playing on the supposedly age-old racial antagonism between Highlanders and lowland Vietnamese. Although the Japanese occupation thwarted French designs, the idea of using Highlanders in guerrilla and counterinsurgency operations aimed at undermining Vietnamese power and sovereignty in the Central Highlands would be a recurring theme in subsequent decades.

Competing Claims to Sovereignty

In 1945, Indochina was transformed by the Japanese coup against the French colonial regime and by the August Revolution, culminating in Hồ Chí Minh’s declaration of independence for Vietnam and the proclamation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN). Hồ Chí Minh and the Việt Minh viewed the Central Highlands and the people who lived there as inalienable parts of the Vietnamese nation. In opposition to the DRVN’s policy of interethnic solidarity, French officials advocated a new version of separate sovereignty for the Highlands, leading eventually to the creation of a new “crown domain” known as the Pays Montagnard du Sud Indochinois (PMSI). The August Revolution had the character of a series of localized attempts to fill the power vacuum left by the March 1945 coup against the French government and the subsequent Japanese capitulation.Footnote 18 In the Central Highlands, the revolution manifested itself in the Ba Tơ uprising, a revolt fueled by existing “tribal” grievances and led by young Highlander intellectuals. After the Japanese coup in March 1945, the opening of detention centers in Kon Tum, Ban Mê Thuột, and Lao Bảo and the release of communist Vietnamese prisoners in the Central Highlands had facilitated contacts between the Việt Minh cadres and Highlanders living in the towns. Educated Jarai and Rhadé youngsters – schoolteachers and medical workers such as Nay Der, Nay Phin, Ksor Ní, and Y Ngông Nie Kdam – embraced the nationalist fervor that agitated Vietnam, and the Việt Minh’s promise of development policies that respected the “national minorities’” own languages and cultures. The Việt Minh literacy campaigns were especially appealing to these young intellectuals. In April 1946, a Việt Minh Congress of the Southern National Minorities took place in Pleiku to elect representatives to the DRVN National Assembly. In a letter to participants, President Hồ Chí Minh stressed the “multinational” (multiethnic) character of the DRVN state and described Vietnam as the country of the Việt majority and the “national minorities” alike.Footnote 19

The French, however, were determined to reassert their authority over Indochina – including the Central Highlands. Already in March 1945, “Free French” leader Charles de Gaulle announced the intent to create a new Fédération Indochinoise, which would offer limited autonomy while preserving French control in economic, political, and military affairs. In the fall of 1945, French forces embarked on a reconquest of southern Indochina, aided by the British occupation force that had arrived to accept the Japanese surrender. In November, a cavalry force under Colonel Jacques Massu (who later became famous for his role in the battle of Algiers) reached Ban Mê Thuột, capital of Đắk Lắk province, and unofficial capital of the Pays moï, where the reconquest was temporarily halted. Over the following year, France and the DRVN engaged in tense negotiations amid intensifying armed clashes.Footnote 20 In this environment, the Central Highlands emerged as a major point of disagreement. In March 1946, just days after French and DRVN officials signed a modus vivendi agreement, the Minister of Colonies Marius Moutet instructed Admiral Thierry d’Argenlieu, the new French high commissioner in Indochina, to investigate the feasibility of creating an autonomous moï territory. Such a move, Moutet knew, was sure to offend the Việt Minh. Although the subsequent creation of the PMSI would be attributed to d’Argenlieu, records show the decision was initiated in Paris.Footnote 21

In May 1946, d’Argenlieu presided over a tribal oath swearing ceremony in Ban Mê Thuột – a custom invented by Sabatier that was presented as a popular demand for direct French rule in the Highlands. D’Argenlieu described the ceremony as a prelude to the establishment of the PMSI ten days later. As the name implied, the new administrative unit was Highlander territory directly under the French-controlled Fédération indochinoise. Unlike the earlier Pays moï, the PMSI comprised five upland provinces that previously belonged to the region of Annam. This excluded important Highlander populations in other parts of Indochina, including several that had resisted French rule. Thus, PMSI territory did not follow any “ethnic boundaries” but the borders of the Vietnamese state that the French aimed to dismember. Significantly, Highlander populations within the boundaries of Cochinchina were excluded from the PMSI because d’Argenlieu carried through his plan for a separate “republic of Cochinchina” in early June, further shoring up the French sphere of influence. On June 21, French troops in the Highlands attacked Việt Minh positions in Pleiku and Kon Tum, just before the start of the decisive French-DRVN conference at Fontainebleau. This bid to seize the remaining territory of the PMSI produced mixed battlefield results, as colonial forces were stopped north of Kon Tum and east of An Khê. But as an attempt to undermine the negotiations in Fontainebleau, d’Argenlieu’s moves were stunningly successful.Footnote 22

Unsurprisingly, the proposed separation of Cochinchina and the PMSI from the territory claimed by the DRVN incited vehement protests from Hồ Chí Minh’s government. During the preparatory Franco-Vietnamese conference at Dalat in April–May 1946, the Việt Minh argued that “Cochinchina was an integral part of Vietnam, whose ethnic, geographic, historical, cultural and psychological unity was impossible to deny.” At Fontainebleau that summer, Hồ Chí Minh asserted that “ethnically, historically, Cochinchina is a part of Vietnam, just like Bretagne or the Bask country is a part of France.”Footnote 23 The Việt Minh claimed to embrace all “nationalities” on Vietnamese territory as part of a “multinational” or multiethnic nation-state. The relations between ethnic groups were likened to family ties, with the Việt or Kinh “elder brother” guiding the younger Highlander siblings into a bright future of maturity and development with Bác Hồ (Uncle Hồ, or Bôk Hô in Bahnar language) depicted as a common ancestor.Footnote 24 According to Hồ Chí Minh, the Kinh majority and the ethnic minorities were “all blood brothers and sisters.” “Rivers can dry up, mountains can wear away,” Bôk Hô declared, “but our solidarity will never decrease.”Footnote 25

The French arguments about Cochinchina and the PMSI were in many respects the mirror image of the DRVN claims, though they rested on strikingly different notions of ethnic and national identities. In a response to Hồ Chí Minh’s protests against the French occupation of the Pays moï, the Interministerial Indochina Committee declared that France had a special responsibility for the minorities, and that “neither geographically, historically nor ethnically, the High Plateaux can be considered a part of Vietnam.”Footnote 26 The French also resorted to kin analogies in order to legitimize their plans to rule an “autonomous” Highlander territory. Like Sabatier, who had once described himself as the Ay Prong (grandfather) with responsibility for “guiding and chiding” (guider et gronder) his Rhadé subjects, French attitudes toward the Highlanders were deeply paternalistic.Footnote 27 In the historical context of rising nationalism, France’s civilizing mission (mission civilisatrice) was recast as the duty to guide all their Indochinese “children” with a just but firm hand. This was clearly expressed in one (of many) propaganda speeches for Highlander audiences, in 1953:

Why does the Resident grumble? It is for the well-being of the Montagnards, not for himself. The Resident, that is France, has come here to bring up the Montagnards like a mother brings up her children. […] you must become equal to the Vietnamese. The Montagnards must be on the same level. It should not be, like before 1945, that the Vietnamese is up there and the Montagnard down below.Footnote 28

In this view, the “dominant peoples” may have reached the age of adolescence, but France had the special responsibility of protecting the minorities and preserving their traditional cultures.

At the Đà Lạt Conference of August 1946, which d’Argenlieu convened to further the development of the Fédération (and to frustrate the talks in Fontainebleau), the French delegation argued for special treatment for ethnic minorities. For the first time in colonial history, Highlanders were officially designated as “civilizations” worthy of protection within autonomous territories, separate from Vietnam but still within the Fédération Indochinoise. For the French, this process was one of “liberation” for the Highlanders. Such moves affirmed de Gaulle’s efforts to preserve the prewar division of Vietnam into five separate pays and also placed the ethnic minorities on equal footing with the majority populations of Indochina. Moreover, by reserving the right to arbitrate conflicts between minority and majority groups, the French sharpened geographic boundaries and ethnic distinctions at the same time.Footnote 29

The French claims were supported by a PMSI delegation of Highlanders that the French had assembled for the occasion. Headed by the president of the customary law court of Đắk Lắk province, Ma Krong, this delegation proclaimed that the DRVN delegation at Fontainebleau should not speak for other “member states” of the Fédération – in this case the PMSI. The delegation also declared that “all the individuals wearing loincloths” should be protected directly by France and acquire independence. In a single sentence, the petitioners circumscribed Highlander identity within the boundaries of the PMSI and also denied any affinity for other Indochinese populations. While two additional “motions” entailed the preservation of minority education in French and of Highlander customary law, another concerned the incorporation of Highlander soldiers into the French colonial army. The emphasis was on Highlander loyalty to the French, which might be contrasted with the solidarity propagated by the Việt Minh. For the French and the PMSI delegation, this loyalty was symbolized by the odyssey of a Rhadé battalion that had followed their French officer through Laos to China after the Japanese takeover in March 1945. Loyalty was also the symbolic substance of the oath-swearing ceremonies in the newly “liberated” towns in the presence of High Commissioner d’Argenlieu. The Highlander “chiefs” who spoke out against “Annamese tutelage” were rewarded with medals, guns, and occasionally a légion d’honneur. But the limits of this “loyalty” were also apparent – especially when the Việt Minh staged its own ceremony only a few days later, in the same area and with many of the same people.Footnote 30

In his study of Việt Minh minorities policy in northern Indochina as a key for understanding the battle of Ðiện Biên Phủ, John McAlister argues that the Việt Minh’s “interests were best served by creating an organization for military participation which gave the minorities opportunities for mobility and status.” McAlister found it “instructive to note the Việt Minh’s effectiveness in using military organization to achieve [political integration]” which in Southeast Asia is thought to depend “on economic or social prerequisites.”Footnote 31 However, the Việt Minh had no monopoly on this practice, since their adversaries attempted the same thing among the southern minorities. Like the Việt Minh, the French saw the Highlanders as prospective soldiers and military allies. But whereas the Việt Minh used the DRVN army as an instrument to tie different groups together, the French needed to create a separate homeland to motivate the Montagnard battalions to fight against Vietnamese nationalism, while also providing avenues for the ambitions of Montagnard warriors.Footnote 32 The ideas of a separate territory and a separate Montagnard army effectively created a Montagnard military elite harboring separatist aspirations. The political effects of this policy would be long-lasting, enduring well beyond the final French military defeats of 1954.Footnote 33

Strategic Developments and Ethnic Tactics in the Central Highlands

After seizing Pleiku, Kon Tum, and An Khê in June 1946, the French expeditionary force encountered heavy PAVN resistance north of the line from Kon Tum to An Khê. Located at the southwestern, inland end of the coastal strip of the provinces of Quảng Trị, Quảng Nam, and Quảng Ngãi, this area was known by the French as the rue sans Joie (street without joy) and it remained firmly in DRVN hands. A military stalemate emerged, with Kon Tum and An Khê as the main French bastions along this front. Later Vietnamese historiographers have glorified the resistance of Hrê, Katu, Kor, and other groups as continuing a tradition of anti-French revolt in alliance with the Việt Minh. In his biography, the Bahnar “hero” Núp is depicted as having led his own village and others against the French, against all odds, deprived of salt, and virtually without support from Việt revolutionaries. In reality, Việt Minh cadres tried to remain in contact with minority groups, and were increasingly successful in organizing anti-French rear-area resistance, resulting in the “rotting away” [pourissement] of French control over population and territory. French actions were increasingly restricted to the major towns and roads. By 1950 the town of Kontum was a French island surrounded by enemy territory.Footnote 34

The French devised several responses to the PAVN military threat. First, they increased recruitment of Highlander youth into the colonial militia, focusing especially on the Rhadé. In a 1949 assessment, the Rhadé were described as “excellent troops” who served in both the regular French forces (5,000) and the Garde montagnarde (2,500).Footnote 35 Although some Highlander youngsters found a military career attractive, the French demand for fighters quickly exceeded voluntary supply, and French-appointed village headmen were seduced or coerced to provide the French army with new recruits by whatever means available. From 1948 onward, French officers reported low morale, evasion of recruitment, and growing desertion rates among Montagnard soldiers. The local socialist French leader Louis Caput was not optimistic about Franco-Highlander relations in the PMSI:

The mountain people of these regions […] certainly did not like the more enterprising Vietnamese, but [they] are beginning to detest singularly the French who recruit them as soldiers, subject them to exactions and impose labor upon them. As a result, there has been growing malaise, an abandonment of work and land, a retreat into the forest, and the least one can say is that the situation in the […] PMSI begins to become very disquieting.Footnote 36

A second response harkened back to the original raison d’être for the French presence: the development of rubber, tea, and coffee plantations. In November 1946 Colonel Massu outlined a plan to enable demobilized French soldiers to establish plantations in Darlac province. The scheme recalled the ancient Roman practice of using legions to colonize conquered territory; it was also reminiscent of Nguyễn Dynasty-era military colonies (đồn điền) established during Vietnam’s “march to the south,” as well as 1930s-era settlement ventures in Laos. Massu felt that a “colonisation à la romaine” was desirable, for it remained “the mission of France in Indochina … to protect the ethnic minorities against the Annamese imperialist tendency.” The plan was welcomed by d’Argenlieu, who stressed the political benefits of the presence of French cadres in the Highlands, as well as the economic advantages of the plantations, which would in theory render the PMSI economically viable. According to one of the settlers, Jacques Boulbet, one of the aims of the colonization was to “secure the bases of a sufficiently viable economy to sustain the thesis of autonomy for the ethnic minorities.”Footnote 37 Although officials in Paris were skeptical about the large scale of the “plan Massu” and the labor problems that it might create, they allowed the experiment to proceed on a limited basis.Footnote 38 By 1949, around one hundred French veterans had settled as colonists in three centers (Ban Mê Thuột, Djiring, and Đắk Mil), partly on previously abandoned plantations. While the results of the colonization effort were duly hailed in public, officials privately noted that “the Montagnard workers come with limited enthusiasm and for strictly regulated periods, in order not to spoil the bit of goodwill, which must be strongly encouraged.”Footnote 39 These concerns were well-founded, because any goodwill was quickly lost due to an increasing resort to forced labor.

The self-defeating nature of the French colonization efforts was evident to officials and other observers, who noted that extractive aspects of the policy nullified any gains from propaganda, medical, or educational programs. The British journalist Norman Lewis documented the cynical defeatism among French plantation owners, who resolved to exploit Highlander labor “for as long as it would last.” He described how owners hired armed gangs to hunt male workers in Highlander villages, and even tried to recruit members of the Garde montagnarde, apparently unconcerned about the resulting discontent. When the abusive behavior of plantation owners was added to the impositions of taxes, corvée labor, and forced recruitment of Montagnard soldiers, the French state’s prospects for winning Highlander loyalty seemed to disappear, just as Louis Caput had feared. Furthermore, the plantations imposed extra burdens on the French military to defend from PAVN attacks. Complaints in the summer of 1950 led to a heated correspondence among senior French leaders about the feasibility of the defense of plantations – but without a clear outcome.Footnote 40

The Military End Game

By the late 1940s, French policy for the Central Highlands had reached a crossroads. The strategy to win Highlander loyalty through separatism and French “protection” of minority rights seemed unsustainable. Meanwhile, geopolitical shifts and the emerging Cold War had forced French officials to reconsider their intransigent stance toward Vietnamese nationalism. By 1949, the looming communist takeover in China had increased the availability of US military aid for the French war effort in Indochina. But US policymakers wanted the French to accommodate noncommunist Vietnamese nationalists so they could be enlisted in the fight against the Việt Minh. These circumstances gave rise to the “Bảo Đại solution,” the scheme under which the former Nguyễn emperor would become head of an ostensibly independent State of Vietnam (SVN) within the framework of de Gaulle’s French Union. But despite his malleability, not even Bảo Đại would endorse a Vietnam that excluded Cochinchina and the PMSI.

In the Élysée Accords of March 1949, Bảo Đại secured a French pledge to respect the territorial unity of Vietnam, as well as promises of SVN diplomatic, financial, and military autonomy. For the time being, however, France continued to wield substantial power throughout Vietnam – especially in the PMSI. Even as France recognized formal Vietnamese sovereignty over the Central Highlands, it demanded a statut particulier (special status) for the Highlands because of “special French obligations” toward the Highlanders. To finesse this apparent contradiction, the French proposed that the five Highland provinces would now be linked to the person of Bảo Ðại as the former emperor’s “crown domain of the PMS.” (Significantly, the ‘I’ that previously designated the Indochinois quality of the PMSI had disappeared when the territory was formally reintegrated into Vietnam.) The relation of the ex-emperor to his crown domain consisted primarily of shares in rubber plantations and hunting lodges, but in June 1949 he presided over the oath-swearing ceremony in Ban Mê Thuột, along with the newly installed French high commissioner, Léon Pignon (Figure 9.2). In a volte-face, the French now acknowledged that “these territories […] indisputably belong to the ancient Empire of Annam.” For the moment, this nominal transfer of sovereignty hardly affected the regime of direct French rule, which was the substance of the “special status.”Footnote 41 The only tangible short-term policy change was a further opening of the Highlands for plantations, via credits and tax exemptions. Nevertheless, the political reverberations of the French shift would echo for decades. Montagnard soldiers were shocked and upset to learn that their contracts with the French Army had been dissolved and replaced by contracts with the newly created SVN Army.Footnote 42 A generation later, in 1965, the Rhadé leader Y Bham Enuol bitterly remembered how the French “arbitrarily, without consulting us, had […] reunited the PMS to the domain of the Crown of Emperor Bảo Ðại.”Footnote 43

Figure 9.2 The former Vietnamese emperor Bảo Đại (standing) reads a speech at an oath-swearing ceremony attended by members of several Highlander minority groups in the city of Ban Mê Thuột in June 1949. Leon Pignon, the High Commissioner of Indochina, is seated in front of Bảo Đại. The ceremony aimed to seal the incorporation of the Central Highlands region into the newly created State of Vietnam, which Bảo Đại led as chief of state.

After 1950, the practical shortcomings of France’s ethnic policy for the Highlands were exacerbated by apparent rapprochement between Highlanders and the DRVN. The steady military advance of the PAVN forces in the Highlands was partly attributed to their accommodation to Highlander culture. The training of communist cadres was increasingly geared to the exigencies of life among non-Việt peoples in the jungle. The “eight orders” given by Hồ Chí Minh professed respect for local populations and their cultural practices, including those of the Highlanders. DRVN accounts told of cadres who totally immersed in local Highlander societies by learning the language, dressing in loincloth, marrying a local woman, and even filing their teeth. Such stories were undoubtedly exaggerated, but they were also widely believed. As observed by the author of a 1951 intelligence report on Việt Minh gains in Darlac province, “The Viet-Minh has a Moi policy, too.”Footnote 44 This realization prompted French military officials to offer more than merely some sort of abstract autonomy in a fictional homeland. Their most important responses included the Action psychologique and the Maquis, both initiated in 1950.

The Action psychologique was set up by Jean le Pichon, who had been commanding Montagnard militia for twenty years. A variation on what the Americans called “psychological warfare,” the French version consisted of propaganda, social action, and military action. Schools were transformed into “formation centers of Montagnard propagators.” These “propagators” took responsibility for the political training of village chiefs, who were warned about the dubious character of DRVN promises of autonomy, and the unreliable nature of the ethnic Việt in general. From 1953, a propaganda journal, Le Petit Montagnard, was available in four languages (Rhadé/Jarai, Koho, Bahnar, and Sedang) and distributed among Montagnard soldiers and other Highlander “brothers.” The “social action,” coordinated with the Catholic mission, consisted of the distribution of salt and of medical care. In the area of “military action,” the PAVN concept of the “fighting village” was adapted to suit French purposes. Characteristically, the French resettled the population of several scattered hamlets into one big village, which would then be defended by armed youths, trained and led by French soldiers. These small-scale resettlement schemes, aimed at isolating enemy guerrillas from village residents, were a harbinger of later US and RVN attempts to concentrate the rural population in strategic hamlets.Footnote 45

Meanwhile, the maquis were commandos who tried to set up counterguerrilla groups in enemy territory, and thus went much further in adapting to local cultures than the action psychologique. Colonel Roger Trinquier, the mastermind behind the maquis, believed it useless to educate “half savage peoples with a limited horizon” in the complex politics of the French Indochina War. The only way to reach them, he argued, was to play on their immediate interests and ambitions, and to revive old antagonisms, especially toward the ethnic Việt. As with the Devereux plan during World War II, the idea was to parachute one or more French commandos of the Groupes de commandos mixtes aeroportés (GCMA) into local communities to set up a self-defense system and to train recruits. The majority of the ten maquis were in the northern mountains, where the most intense combat of the war took place. In the Central Highlands the French capitalized on a revolt of the Hrê “tribe” in Quảng Ngãi against the DRVN. Among the Hrê, the cadres had felt sufficiently safe to step up their exactions in terms of foodstuff and labor, and to settle thousands of Việt migrants in Hrê territory, thus making the same political mistake as the French with their plantations. When the Hrê revolted against this regime by killing hundreds of ethnic Vietnamese in their midst, the French immediately sent Captain Pierre Hentic to try and turn the Hrê, who feared a PAVN retaliation, into “partisans.” One French agent later recounted his experience among the Hrê in romanticized terms, relating how he learned the language and adopted their lifestyle in order to win their confidence, while also marrying a local girl in order to ally himself to a Hrê leader. He told of how he baptized his partisans the “Hrê independence movement” and claimed they fought only for themselves – albeit against the same enemy as France, as Colonel Trinquier aptly noted.Footnote 46

Although the action Hrê lasted until 1954, the overall French military position in the Highlands deteriorated steadily after 1950. Despite the initial success of the Hrê maquis, Hentic’s eight battalions proved no match for regular PAVN units supported by Highlander guerrillas. Thus, the French were never able to reconquer the “street without joy” and lost their grip on the coastal districts of Quảng Ngãi and Bình Định provinces. As the Việt Minh grew stronger, the pressure on French positions in the Central Highlands mounted, especially around the towns of Kon Tum and An Khê. Located on route colonial 19, one of just three roads connecting the Highlands to the Vietnamese coast, An Khê had been the site of a celebrated French victory in 1946–7 but would soon become the scene of one of France’s bloodiest defeats.

In January 1954 the French commander General Henri Navarre launched Opération Atlante, aimed at conquering the coastal strip of Quảng Ngãi and Bình Định provinces. This required a concentration of military forces at the same time as Điện Biên Phủ was being turned into a massive French fortress. This left the Central Highlands exposed, and General Võ Nguyễn Giáp directed Việt Minh regiments to attack French posts north of Kon Tum.Footnote 47 In response, Navarre ordered the deployment of a battle-hardened group of more than 800 commandos who had fought the Chinese and North Korean armies alongside US forces in Korea. Upon arrival in the Highlands, they merged with local Việt troops and GCMA consisting of Rhadé and Jarai fighters to form the 3,500-strong Groupe Mobile 100 (GM 100). The GM 100 was sent to protect Kontum and Pleiku, and quickly had bruising battles at Đắk Tô, Đắk Đoa, and Plei Rinh with the PAVN’s 803rd Regiment, forcing the French to give up the town of Kontum, site of a French Catholic mission since the 1850s.

One month after the famous Việt Minh victory at Điện Biên Phủ, French commanders realized that their forces at An Khê also faced the prospect of being overrun. The GM 100 was sent to relieve the town and open Route 19, but it was ambushed at the Mang Yang pass on June 24. During four days of combat, the group sustained heavy casualties and the loss of most of its vehicles and artillery, making it the third-worst French defeat after Cao Bằng (1950) and Điện Biên Phủ (1954), both in the north. When the remainder of these forces were sent to defend the road between Ban Mê Thuột and Pleiku, they were almost annihilated at the Chư Dreh pass on July 17. Of the nearly 800 Korean War veterans who joined the GM 100, only 107 survived. By the time of the ceasefire negotiated at Geneva, only Pleiku, Ban Mê Thuột, and Đà Lạt were still in French hands, albeit extremely tenuously. According to Bernard Fall, “whatever tribesmen had remained loyal to the French were now in the posts and camps, and the remainder retreated with the Việt Minh into the inaccessible hills a few miles off the paths and roads.”Footnote 48

The defeat at An Khê was born not only of the shortcoming in French military strategy, but of the deeper problems lurking in France’s ethnic policies for the Central Highlands. Having long fostered ethnic separatism in the name of “protecting” Highlanders from ethnic Vietnamese encroachment, French officials discovered that the action psychologique and other efforts to win Highlander support were no match for the political operations of the DRVN. Although both sides used a combination of persuasion and coercion in their efforts to mobilize local populations, French efforts to secure Highlander “loyalty” were undermined by the attempts to accommodate Vietnamese nationalism. These contradictions, combined with the increasingly onerous French demands for Highlander land and labor, helped to burnish the appeal of the Việt Minh’s call for multiethnic solidarity (Map 9.1).

Map 9.1 The locations of the major ethnic groups in central Vietnam.

Conclusion: The Legacy of An Khê

The destruction of the GM 100 at An Khê in 1954 sealed the French defeat in the Central Highlands. At the same time, it also marked the failure of France’s separatist policies for the region. This failure cannot be explained merely as a result of French military missteps (although those are clearly evident in hindsight). Instead, the war in the Central Highlands was the culmination of a long-running contest over different configurations of ethnicity, territory, national sovereignty, and state power. Although by the spring and summer of 1954 the DRVN’s “ethnic policy” for the Highlands prevailed over that of the French, this did not mean that the broader debates over Highlander loyalties and identities had been resolved – only that they were about to move into a new phase.

Following the partition of Vietnam under the international accords negotiated at Geneva in 1954, administrative responsibility for the Central Highlands passed formally to the SVN (soon to be reborn as the Republic of Vietnam, or RVN). Unlike his French predecessors, RVN founder Ngô Đình Diệm was determined to establish Vietnamese sovereignty over the Highlands.Footnote 49 He proposed to do this via cultural assimilation of Highlander communities and settlement programs for ethnic Vietnamese – moves that quickly provoked resistance in the form of the multiethnic Bajaraka Movement (Bahnar, Jarai, Rhadé, and Kơho) formed in 1958 and in the Trà Bông revolt of the Hrê and Cor minorities during 1959–60.Footnote 50 These uprisings attracted the attention of DRVN leaders in Hanoi, who moved quickly to recruit the rebels into the communist-led National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF). They also prompted responses from the US military, who dispatched special forces units to establish Highlander militias reminiscent both of the French-led Battalions Montagnard and Georges Devereux’s never-implemented “special plan” of 1943.Footnote 51 By the early 1960s, the Central Highlands had once again become a theater of combat. The stage had thus been set for a new and even more violent multisided conflict over questions of loyalty, autonomy, solidarity, and ethnic identity.