The term ‘social media’ broadly refers to any website or application that allows its users to generate and exchange content(Reference Cochrane, Hutcheon and Karakochuk1). In recent years, the number of active social media users worldwide has continued to increase, rising from 2·73 billion in 2017 to 4·59 billion in 2022(2). By 2027, this number is projected to reach 5·85 billion.

In particular, adult women of reproductive age are highly engaged users of social media. Globally, 35 % of Facebook’s and 40 % of Instagram’s current users are females aged between 18 and 54 years(3,4) . Across all age groups, the highest proportion of Facebook’s and Instagram’s female users was aged 25–34 years, representing 13 % and 15 % of users, respectively.

As a result of their global accessibility and scalability, social media platforms are emerging as a favourable tool in health research. This includes health promotion interventions that aim to promote changes in health and health behaviours, such as physical activity levels, diet quality, anthropometric measurements and psychological health(Reference Petkovic, Duench and Trawin5). In addition, online interventions can easily be accessed by participants on a range of devices, including computers, laptops, mobile phones and tablets, at their convenience. These interventions may also be more cost effective than traditional interventions(Reference Ashford, Olander and Ayers6,Reference Lara-Cinisomo, Ramirez Olarte and Rosales7) .

This ease of access could be particularly advantageous for women of reproductive age, especially those with infant children, as it may allow a population with competing family, work and personal demands to participate in health promotion interventions at their convenience while eliminating the need to attend time-consuming in-person sessions(Reference Ashford, Olander and Ayers6,Reference Bennetts, Hokke and Crawford8) . However, little is known about how health promotion interventions conducted via social media affect the health and health behaviours of women of reproductive age, or whether this is an acceptable platform for intervention delivery. To date, no review has provided a synthesis of the field to describe health promotion interventions conducted via social media and examine their effect on health-related outcomes and behaviours of women of reproductive age. If these types of interventions are shown to be acceptable and effective for improving women’s health, further research in this area would be supported, including the design of health promotion interventions to be delivered at-scale via social media to improve population health.

Therefore, this scoping review aimed to primarily describe health promotion interventions delivered to women of reproductive age via social media. Further, this review aimed to determine whether the health promotion interventions have a positive effect on the mental or physical health or health-related behaviours, including diet and exercise, of adult women of reproductive age and determine the level of engagement with, and acceptability of, the intervention by women.

Materials and methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)(Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin9) was used to guide this systematic review. Additionally, the review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews on 8 June 2022 and was assigned the study protocol registration number 336812.

Search strategy for study identification

Six electronic databases were systematically searched on 13th May 2022 by one author (MH) to identify relevant studies: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL Complete, Cochrane Library and Scopus. Advanced searches in titles, abstracts and keywords were conducted using a combination of population terms (e.g. postpartum women, pregnant women), intervention terms (e.g. health promotion, social media, internet-based intervention) and outcome terms (e.g. mental health, depression, anxiety, physical activity, diet). To ensure a comprehensive search of the literature, no restrictions were placed on comparison interventions or year of publication. Search strategies were adjusted for each database (online Supplemental Table 1). Reference lists of retrieved papers were also reviewed to identify relevant publications for inclusion.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the present review if they (1) recruited adult women of reproductive age (mean age 18–45 years)(10), including pregnant and postpartum women; (2) delivered a health promotion intervention primarily via social media; (3) assessed and reported at least one health-related outcome (e.g. mental health, weight, blood pressure) or behaviour (e.g. knowledge, awareness, diet, physical activity, infant feeding practices) pre- and post-intervention; (4) were written in English and (5) were accessible in full text. Studies were excluded if they (1) recruited mixed populations (e.g. adult males or adolescent females in combination with adult women) and did not disaggregate data for adult women; (2) only used social media for recruitment purposes; (3) delivered an intervention primarily face-to-face, or via mobile phone applications (not including mobile versions of social media platforms), websites, text messages, phone calls and/or emails; (4) only used social media as a forum for support during the intervention period; (5) did not report any health-related outcomes or behaviours or (6) were a systematic review, meta-analysis, study protocol or conference abstract.

Selection of studies

The study selection process was undertaken using Covidence Systematic Review Software. Studies identified by the six electronic databases were exported into Covidence and duplicates were automatically identified and removed. Both authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of all studies and irrelevant articles were excluded. The remaining studies progressed to full-text screening and were further assessed against eligibility criteria. This stage was also conducted in duplicate. Discrepancies throughout the study selection process were discussed and resolved by consensus between the two authors.

Quality assessment

Although not a requirement of a scoping review, a risk of bias assessment was completed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools. The corresponding checklist was utilised for each study design as appropriate(Reference Tufanaru, Munn and Aromataris11,Reference Moola, Munn and Tufanaru12) . For each item, possible answers included ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’ or ‘not applicable’. Studies were classified as low risk of bias if they scored ‘yes’ for at least 70 % of items, moderate risk if they scored between 50 and 69 % and high risk if they scored less than 50 %(Reference Melo, Dutra and Rodrigues Filho13). Both authors independently utilised the relevant checklist for each study type to determine the risk of bias for the included studies. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and synthesis

A data extraction form was developed in Microsoft Excel and relevant study characteristics were extracted by one author (MH). This included publication information (first author, year of publication, study location), methodological details (study design, sample size), participant demographics (age, gender, pregnancy status, ethnicity/socio-economic status), intervention details (social media group, comparator group, duration, retention, data collection methods) and study outcomes (main findings for health outcomes or behaviours, findings regarding the success of the social media intervention, i.e., engagement or acceptability). The completed data extraction form was reviewed for accuracy and completeness by the other author (MG). Given the limited number of studies included in the present review and the heterogeneity of these studies, the results were synthesised and presented in narrative form.

Results

Study selection

The combined database searches produced a total of 873 records and 129 additional records were identified from reference lists of retrieved articles (Fig. 1). Following the screening process, nine studies were eligible for inclusion in this review.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram

Study characteristics

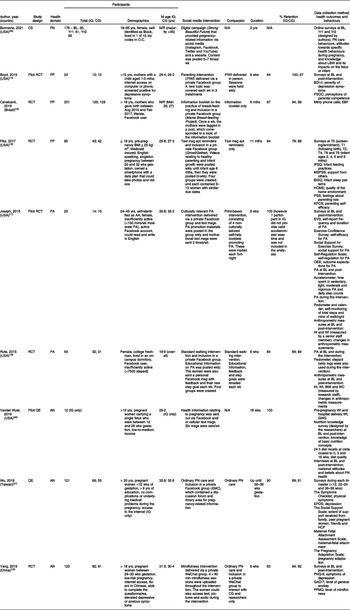

Study design

The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Study designs included randomised control trial(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19), quasi-experimental(Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20,Reference Wu and Hung21) and cross-sectional(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22). Most studies (n = 6) were conducted in the USA(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16–Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18,Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20,Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) , with the remaining studies conducted in Brazil(Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15), Taiwan(Reference Wu and Hung21) and China(Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19). The health domains assessed were prenatal health(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22), antenatal health(Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19–Reference Wu and Hung21), postpartum health(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16) and physical activity(Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18) . Studies were published between 2015 and 2021. Most interventions (n = 8) were conducted for less than 1 year (i.e. between 2 and 11 months)(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Wu and Hung21) and the remaining study intervention was implemented for 2 years(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22). No studies provided follow-up beyond the intervention period. Seven studies included a control group(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19,Reference Wu and Hung21) , such as standard care or a face-to-face intervention.

Table 1 Characteristics of the included studies

AN, antenatal; Apt, appointment; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; BISQ, brief infant sleep questionnaire; BL, baseline; CG, control group; CS, cross-sectional study; EBF, exclusive breast-feeding; EMC, Expectant Mother Club; EPDS, Edinburgh postnatal depression scale; EVS, exercise vital sign questionnaire; FFMQ, five facets of mindfulness questionnaire; GAD-7, generalised anxiety disorder scale; GWG, gestational weight gain; HCP, health care professional; HOME, home observation for measurement of the environment; Ht, height; IFSQ, infant feeding style questionnaire; IG, intervention group; KPCS, Karitane parenting confidence scale; LBW, low birth weight; M, mean; Mdn, median; Min, minute; Msg, message; MSPSS, maternal scale of perceived social support; Mth, month; N/A, not applicable; N/R, not reported; O.C., Orange County; OEE, outcome expectation scale for exercise; PA, physical activity; PHQ-9, the patient health questionnaire; PIWI, Parents Interacting With Infants; PN, prenatal; PP, postpartum; PSOC, parenting sense of competence scale; PSS, parental stress scale; QE, quasi-experimental study; RCT, randomised control trial; WC, waist circumference; Wk, week; Wt, weight; Yr, year.

Study sample

The number of participants in each study ranged from 12 to 251 (mean number of participants = 98). Post-intervention retention rates for all studies except Bonnevie et al.(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) ranged from 83 % to 100 % (mean retention = 90 %). Bonnevie et al.(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22), which had a greater uptake of cross-sectional survey completion as the duration of the intervention went on, had 30, 61 and 85 women complete a cross-sectional survey at baseline, Year 1 and Year 2, respectively. Most studies (n = 6) recruited participants from hospitals(Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15,Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19) , clinics(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16,Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) or medical centres(Reference Wu and Hung21). Only one study(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) used advertisements on social media for recruitment.

The mean age of participants in the majority of included studies (n = 7) ranged from 18 to 36 years(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16–Reference Wu and Hung21) . However, two studies(Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15,Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) did not report a mean age and instead noted that they recruited women aged 18–65 years (majority were under 45 years)(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) or > 18 years (median age was 26 and 27 years in the intervention and control group, respectively)(Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15). Six studies exclusively recruited pregnant(Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16,Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19–Reference Wu and Hung21) or postpartum women(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15) . Fiks et al.(Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16) and Vander Wyst et al.(Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) further restricted their inclusion criteria to low- to medium-income women, Boyd et al.(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14) to mothers with postpartum depression and Yang et al.(Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19) to women with mild to moderate symptoms of anxiety or depression. Although Bonnevie et al.(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) focused on recruiting Black women, 21·1 %, 29·5 % and 20·0 % of participants at baseline, Year 1 and Year 2, respectively, were reportedly pregnant. Six studies reported on participant ethnicity. All or most participants (i.e. >80 %) in four studies were African American/Black(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16,Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) , whereas the other two studies primarily recruited White women(Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18,Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) .

Intervention characteristics

Eight studies utilised Facebook to deliver their intervention, either in isolation (n = 7)(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18,Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20,Reference Wu and Hung21) or in conjunction with other social media platforms (n = 1)(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22). Bonnevie et al.(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) delivered a digital campaign (‘Strong Beautiful Future’) for 2 years that focused on providing pregnancy-related health information via four social media platforms (i.e. Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube) and a website. Vander Wyst et al. (Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) also communicated pregnancy-related health information. However, this was provided via Facebook messages for 18 weeks. Neither of these studies included a control group. The other six studies(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18,Reference Wu and Hung21) created private Facebook groups that could only be accessed by participants in the intervention group. Half of these studies provided information relating to postpartum health for 8 weeks(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14), 6 months(Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15) or 11 months(Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16). Two studies(Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18) used these groups for 8 weeks to promote physical activity. One study(Reference Wu and Hung21) provided health information to pregnant women up until weeks 36–38 of their pregnancy. All six studies included a control group. The final study(Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19) utilised WeChat to deliver an 8-week mindfulness intervention to pregnant women with mild to moderate symptoms of anxiety or depression. Results were compared with a control group.

Outcomes and measures

Seven studies(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16,Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19–Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) used self-reported questionnaires to collect outcome data pre- and post-intervention(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19,Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) or at three(Reference Wu and Hung21,Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) to six different time points(Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16). To assess physical activity, two studies(Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18) used a pedometer, accelerometer and diaries, or solely a pedometer, before, during or after the intervention. Three studies(Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18,Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) collected anthropometric measurements, such as weight, height and waist circumference. One study(Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) also conducted interviews with the participants pre- and post-intervention, while another(Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15) utilised monthly phone calls to collect data.

Studies with a control group

Antenatal health

The results of the included studies are presented in Table 2. Two studies(Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19,Reference Wu and Hung21) evaluated pregnancy-related health outcomes and behaviours in both an intervention and control group using self-report questionnaires. In one of these studies(Reference Wu and Hung21), both the control and Expectant Mother Club intervention group experienced significant improvements in pregnancy adaptation at Time 3 and maternal-fetal attachment at Times 2 and 3 when compared with pre-intervention. There were no differences in outcomes observed between groups.

Table 2 Results of the included studies

AMDR, acceptable macronutrient distribution range; Avg, average; BL, baseline; CG, control group; CHO, carbohydrate; Dr, doctor; EBF, exclusive breast-feeding; EMC, Expectant Mother Club; EVS, exercise vital sign questionnaire; FFMQ, five facets of mindfulness questionnaire; g, gram; GAD-7, generalised anxiety disorder scale; IFSQ, infant feeding style questionnaire; IG, intervention group; kcal, kilocalorie; LBW, low birth weight; M, mean; Mdn, median; Min, minute; Msg, message; MSPSS, maternal scale of perceived social support; Mth, month; N/A, not applicable; N/R, not reported; PA, physical activity; PHQ-9, The Patient Health Questionnaire; PN, prenatal; PP, postpartum; Pr, protein; WC, waist circumference; Wk, week; Wt, weight; Yr, year.

* Indicates significance.

In the other study, while adherence to daily mindfulness practice was relatively low, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19) found significant improvements in depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as an increase in mindfulness skills, in the intervention group post-intervention. Conversely, changes in depression and anxiety symptoms post-intervention were not significant for the control group. Furthermore, a greater number of women in the intervention group had no symptoms of depression or anxiety when compared with the control group post-intervention. Lastly, for the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire, the overall scores, the scores for the observing subscale (corresponding to attention monitoring) and the scores for the non-judgement and non-reactivity subscales (corresponding to acceptance) significantly improved for the intervention group but not the control group.

Postpartum health

Three studies(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16) evaluated health outcomes or behaviours in postpartum women using self-report questionnaires(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16) or by contacting participants via phone(Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15). Boyd et al. (Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14) observed a greater reduction in depression symptoms in the intervention group compared with the control group post-intervention. Additionally, parenting competence scores increased in the intervention group and decreased in the control group.

In addition to maternal health outcomes, infant feeding practices were also impacted by postpartum interventions. The second study(Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16) identified significantly healthier feeding practices in the intervention group. These mothers were less likely to feed their children cereal in their bottles at 6 months and pressure their children into finishing their food at 9 months. Post-intervention, scores for the Infant Feeding Style Questionnaire were higher in the intervention group. However, infant feeding beliefs, the timing of solid food introduction, infant sleep, screen time, household television use, the timing of the initiation of regular ‘tummy time’ and other measures of maternal well-being did not differ between the groups.

Cavalcanti et al.(Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15) found a significant difference in the median exclusive breast-feeding duration, with a difference of 63 d between the intervention and control groups. At the 6-month follow-up, one-third of participants in the intervention group were still breast-feeding, compared with under 10 % in the control group indicating that participation in the intervention reduced early interruption of breast-feeding in the first 6 months by 62 %.

Physical activity

Two studies assessed physical activity outcomes in either adult(Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17) or college-aged women(Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18) in an intervention and a control group. Using a range of self-reported (questionnaires and calendars) and objective (accelerometers and pedometers) data, Joseph et al.(Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17) found significant between-group differences for sedentary behaviour, light physical activity and moderate physical activity from pre- to post-intervention. Sedentary behaviour decreased in the intervention group and increased in the control group. While light physical activity increased in both groups, a significantly greater increase occurred in the intervention group. Moderate physical activity increased in the intervention group and decreased in the control group. No significant changes in the data captured by the accelerometers were found for either group. For both groups, the number of self-reported steps per day remained stable until week 6 and then declined until the end of the intervention, significantly for the intervention group only.

Results of the questionnaires demonstrated a significant increase in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in the intervention group and stable results in the control group. In addition, these data showed significantly greater increases in physical activity, self-regulation for physical activity and social support from family in the intervention group. Self-regulation for physical activity was the only significant increase found in the control group and the significant between-group difference for changes in outcome expectations for physical activity favoured the control group. BMI remained stable for all participants from pre- to post-intervention.

Rote et al.(Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18) investigated changes in steps per day and anthropometric measurements. Although both groups achieved significant increases in the number of steps per day, a more significant increase occurred in the intervention group. In both groups, a lower baseline activity level and baseline steps per day predicted a greater increase in steps per day.

Regarding anthropometric measurements, a significant decrease in waist circumference was observed in the intervention group. However, there were no significant changes in the control group.

Studies without a control group

Prenatal health

Bonnevie et al.(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) evaluated prenatal health outcomes and behaviours in only an intervention group. Questionnaire results demonstrated that their campaign had a positive impact on the target population. For example, over time, there was increased: (1) awareness that regular check-ins with a doctor can lead to healthier babies; (2) awareness of the safe amount of weight gain during pregnancy and (3) knowledge of the impacts of low birth weight into adulthood. However, due to the small sample size of this study, none of the results achieved statistical significance.

Antenatal health

Vander Wyst et al.(Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) assessed antenatal health outcomes and behaviours in only an intervention group using both self-reported (questionnaires and interviews) and objective (hospital delivery weight) data. Regarding diet quality, mean caloric consumption did not significantly change. Protein and carbohydrate intakes were within the acceptable macronutrient distribution range at baseline and post-intervention. Conversely, pre-intervention fat intake was higher than the acceptable macronutrient distribution range and although it reduced post-intervention, it remained slightly above the acceptable macronutrient distribution range. Compared with other main meals, breakfast was skipped most often. None of the women gained less than the recommended amount of weight; however, around two-thirds gained excessive weight during their pregnancy. In their interviews, the women mentioned making dietary changes for the health of their babies and exercising during pregnancy, not only for the health of themselves and their babies but also to help with postpartum weight loss. Furthermore, although this intervention was well-received by the women, it did not lead to large changes in dietary quality or knowledge.

Social media engagement and acceptability

Eight of the included studies(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16–Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) evaluated social media engagement, defined as any measure of social media intervention use, or acceptability, defined as any measure of participant satisfaction with the intervention (Table 2). These measures were assessed using a variety of methods, including self-report questionnaires, interviews with participants and activity in the Facebook groups.

Social media engagement

Social media engagement was examined by seven studies(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16,Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18–Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) . Bonnevie et al.(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) used Google Analytics to collect metrics and assess digital engagement with their social media campaign. Engagement remained strong throughout the 2-year intervention period. Aside from average monthly Facebook impressions and average daily Facebook reach, all other digital metrics increased between Years 1 and 2. Notably, Instagram had the highest level of engagements (i.e. likes, comments, shares, video views or post clicks) with 476 in Year 1 and 678 in Year 2. This was followed by Facebook and then Twitter.

Boyd et al.(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14) used the number of participants who viewed the weekly content posted in the ‘Parents Interacting with Infants’ Facebook group to assess engagement. All mothers in the intervention group viewed at least one of the weekly posts, whereas only one-quarter of mothers in the control group attended at least one in-person session. Average attendance by the intervention group was also considerably higher (83 % v. 3 %).

Fiks et al.(Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16) evaluated engagement by tracking the number of Facebook posts and comments in the ‘Grow2Gether’ intervention. Both the mothers and the facilitators posted about the curriculum topics, with almost all posts (99 %) focusing on infant and parenting topics. Overall, the most frequently discussed topics were feeding (63 conversations) and maternal well-being (51 conversations). The number of Facebook posts gradually decreased throughout the intervention period from 1953 during the first 7 weeks (prenatal period) to 553 when the infants were aged between 6 and 9 months. This study also concluded that individual participation was only inversely associated with infant weight-for-length Z-score and participation in the intervention group did not result in higher scores on the Maternal Scale of Perceived Social Support questionnaire.

Rote et al.(Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18) determined engagement in their Facebook Social Support Group by tracking the number of times the participants posted in this group and their interaction with the intervention materials. Engagement levels varied with participants interacting with between six and thirty-two posts. In addition, engagement decreased throughout the intervention. However, this was not a significant predictor of change in physical activity, nor did adherence to the intervention predict changes in the number of steps per day.

Vander Wyst et al. (Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) measured passive engagement with Facebook messages by tracking how many messages each participant viewed. In addition, URL to health websites and videos were included in the messages and active participation was assessed by tracking the number of clicks on each link. A median of 92 % of the messages were viewed by the participants and links relating to exercise and weight gain were clicked on the most. Links directing the mothers to healthy snacks, recipes and relaxation/music were also of particular interest.

After the intervention, Wu and Hung(Reference Wu and Hung21) utilised a self-report questionnaire to collect information regarding the participant’s virtual community use preferences. Most participants (76 %) were classified as ‘low-adherence’, as they spent less than 150 min/month on the Expectant Mother Club. Mothers in the ‘high-adherence’ group reported significantly higher satisfaction with the library information. Lastly, higher adherence to the Expectant Mother Club was observed in first-time mothers and women whose pregnancy was assisted by a technology treatment.

Yang et al.(Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19) used self-report and login data from the WeChat application to determine engagement. While most women (84 %) completed at least three mindfulness meditations, adherence to daily mindfulness practice was relatively low. On average, the women completed 3·25 mindfulness meditations per week.

Social media acceptability

Five studies(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16,Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19,Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) investigated the acceptability of social media interventions. Boyd et al. (Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14) used a 5-point Likert scale (with 1 = low and 5 = high) to assess satisfaction with the weekly sessions and the overall intervention. Favourable scores were observed for both measures, with mean scores ≥3·6.

Similarly, Fiks et al.(Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16) used a Likert scale, as well as open-ended questions, to evaluate acceptability when the infants were aged 2, 6 and 9 months. Positive feedback was received from most participants. For example, most mothers described the ‘Grow2Gether’ Facebook group as ‘helpful’ or ‘fun’ in response to ‘What do you think of the peer group?’, and 88 % answered ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ when asked ‘I would recommend this program’ and ‘the program was helpful’.

A 26-item questionnaire was utilised by Joseph et al.(Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17) to determine the acceptability of the content of the physical activity promotion materials/text messages and the platforms used to deliver the intervention. This was compared with a 19-item satisfaction survey completed by the control group. Results from these surveys supported the intervention program. A greater proportion of participants in the intervention group gained physical activity knowledge (100 % v. 53 %) and found the intervention ‘helpful’ or ‘very helpful’ in promoting physical activity (79 % v. 27 %). The physical activity promotion text messages were also well-received by the intervention group, with most participants gaining physical activity knowledge (93 %) and finding them ‘helpful’ or ‘very helpful’ (79 %). Additionally, the intervention participants rated the overall intervention higher, with almost double the number of participants reporting they were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with the intervention compared with the control group (86 % v. 47 %).

Vander Wyst et al. (Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) conducted follow-up interviews with each participant to gain feedback on their Facebook message intervention. During these interviews, all mothers reported finding the messages helpful. In particular, messages relating to dietary suggestions, recipes, comfortable sleep and health reminders were well-received.

To obtain feedback on their mindfulness intervention, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19) sent the participants a self-report questionnaire after the final session. Most (87 %) found the intervention to be beneficial and all mothers learnt attention monitoring skills. However, it was more challenging to learn the ability to tolerate discomfort, adopt an accepting attitude towards all experiences and maintain an accepting attitude.

Risk of bias

Three randomised control trials were judged as low risk of bias(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15,Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19) and three as moderate risk(Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16–Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18) (online Supplemental Table 2(a)). The cross-sectional study was judged as moderate risk(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) (online Supplemental Table 2(b)). Both quasi-experimental studies were judged as low risk(Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20,Reference Wu and Hung21) (online Supplemental Table 2(c)).

Discussion

This is the first review to examine the nature, effectiveness and acceptability of social media-delivered health promotion interventions in adult women of reproductive age. The interventions were diverse and differed in terms of their comparator groups, duration and data collection methods. Despite this diversity, our results indicate that social media is a potentially useful and acceptable avenue for improving a range of health outcomes and behaviours in adult women of reproductive age. In the nine studies identified, a range of health outcomes and behaviours were targeted, including diet quality, breast-feeding duration, physical activity and mental health, in mothers, expectant mothers and women of reproductive age.

Social media-delivered health promotion interventions

In this review, the most used social media platform was Facebook, with six studies(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18,Reference Wu and Hung21) creating a private Facebook group, one study(Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) sending health information via Facebook messages and one study(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) delivering part of their social media campaign via Facebook. Only one study(Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) used more than one social media platform. Results from this study indicated that Instagram had the highest level of monthly engagements compared with Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. This finding is consistent with current data, which demonstrates that a higher percentage of Instagram’s global users are women of reproductive age(3,4) . The social media landscape is constantly changing and evolving. Therefore, future research should consider which social media platform their target audience engages with the most to deliver effective interventions.

Aside from the platform used for intervention delivery, our review highlighted a high degree of diversity among interventions, including their use of comparator groups, duration, data collection methods and outcomes assessed. Similarly, this diversity has been reported by other systematic reviews, including a review examining the effect of interactive social media interventions on health outcomes in the general adult population(Reference Petkovic, Duench and Trawin5), another assessing computer- or web-based interventions in perinatal mental health(Reference Ashford, Olander and Ayers6) and another assessing the influence of social networking sites on health behaviour change(Reference Laranjo, Arguel and Neves23). These findings highlight the need for greater consistency across future studies, including outcomes assessed and targeted populations, to identify intervention components that are most effective in women of reproductive age.

Changes in health outcomes and behaviours

All the included studies reported positive changes in health outcomes and behaviours from baseline to post-intervention. However, not all changes achieved statistical significance. Findings from the five studies(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18) that focused on either postpartum health or physical activity were primarily positive and significant differences were observed between the intervention and control groups including a greater reduction in depression severity and increased parenting competence(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14), longer duration of breast-feeding(Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15), healthier feeding practices(Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16) and increased physical activity(Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18) . However, in studies that focused on prenatal or antenatal health(Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19–Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) results were mixed with few significant findings. As prenatal and antenatal care traditionally involves regular contact with a healthcare professional (e.g. midwife, obstetrician or general practitioner)(Reference Catling, Medley and Foureur24), the impact of these additional social media interventions may have been reduced. Conversely, the frequency of this contact decreases postnatally. Therefore, as women may not be receiving as much health information or support, they may be more likely to engage with and benefit from social media interventions during the postpartum period.

Similar results were found in a 2021 systematic review(Reference Petkovic, Duench and Trawin5) that examined the effect of interactive social media interventions on health outcomes in the general adult population (i.e. males and females aged > 18 years). While not specific to adult women of reproductive age, six of the nine studies included in our review were also included in this 2021 systematic review. Both reviews found evidence that social media interventions can improve a range of health outcomes and behaviours.

Social media acceptability and engagement

Our findings suggest that social media interventions have higher rates of acceptability and engagement when compared with traditional in-person interventions and standard care procedures. Most noticeably, Boyd et al. (Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14) observed an average attendance of 83 % in the group receiving the Parents Interacting with Infants parenting intervention via Facebook compared with only 3 % in the group attending in-person sessions. With traditional in-person interventions, only participants who can travel to the specified location at a fixed time will receive the intervention(Reference Lee and Cho25). This can be a significant challenge for women of reproductive age, especially mothers and expectant mothers with competing priorities. Social media interventions address this limitation by allowing women to participate in an intervention at a time and place convenient to them. Moreover, given women are highly engaged users of social media, and these platforms are easily accessible and of a low cost, the use of social media in health promotion interventions for this population has great potential.

Strengths and limitations

This review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA-ScR guidelines. A systematic search in six databases combined with comprehensive hand searching was implemented to capture relevant records. While the search was completed by one author, the screening process, quality assessment and data extraction were completed in duplicate.

However, the results of this review should also be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, our understanding of the long-term effectiveness of health promotion interventions conducted via social media in adult women of reproductive age is limited. Most studies (n = 6) were conducted for less than 6 months(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Cavalcanti, Cabral and de Toledo Vianna15,Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17–Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20) , and no studies provided long-term follow-up to assess if changes in health outcomes and behaviours were maintained beyond the intervention period. While no studies reported adverse events in the short term, it is unclear as to whether this would also be the case if the interventions were implemented for an extended period. Moreover, further research is required to ascertain the long-term efficacy of social media interventions.

It is also important to consider that most studies (n = 8)(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14–Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Yang, Jia and Sun19–Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) used self-report data to assess changes in health outcomes and behaviours. While not the primary mode of delivery, several studies included additional intervention components, including information booklets and text messaging. These components may have contributed to the overall intervention effect; therefore, findings may not be attributed solely to the social media-delivered aspect of the intervention.

Several factors restrict the generalisability of our results. As this is an emerging area of research, a limited number of studies were included in the present review. Most of these studies had a small sample size. Therefore, it is possible that the included studies were subject to small-study effects, whereby smaller sample sizes show larger and more favourable intervention effects(Reference van Enst, Naaktgeboren and Ochodo27). In addition, of the six studies(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16–Reference Rote, Klos and Brondino18,Reference Vander Wyst, Vercelli and O’Brien20,Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) that provided information on the ethnicity of their participants, four(Reference Boyd, Price and Mogul14,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16,Reference Joseph, Keller and Adams17,Reference Bonnevie, Rosenberg and Goldbarg22) included mainly African American/Black subjects from developed countries. Given the practicality of health interventions in adult women varies according to a range of factors, including ethnic and economic(Reference Kumari28), results may not be generalisable to all females of reproductive age. This highlights the need for additional studies with adequate sample sizes and diverse populations, including women of varying ethnicities and at different life stages.

Lastly, most studies were judged as having a low to moderate risk of bias. This, in addition to the small study samples, short intervention durations and the absence of comparator groups in some studies, may affect the certainty of our evidence.

Conclusion

To date, there have been limited health promotion intervention studies delivered via social media to women of reproductive age, with high heterogeneity in all aspects of studies. Based on the available evidence, health promotion interventions conducted via social media appear to be acceptable and effective for improving a variety of health outcomes and behaviours in adult women of reproductive age. Our findings suggest that health promotion via social media may be ideal for this population, and deliverable, at scale. However, further research is required to prove its effectiveness and superiority over other intervention strategies.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This study was supported by the University of Sydney, Rewarding Research Success Grant (01/01/2022-31/12/2022) and AHRA Women’s Health Research and Translation Network, Early and Mid-Career Researcher Award (01/07/2021-30/06/2022).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authorship

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: M.G.; data collection: M.H.; analysis and interpretation of the results: M.H. with support from M.G.; manuscript preparation: M.H. with support from M.G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics of human subject participation

Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002300246X