There was not one Vietnam, argues Christopher Goscha, but many.Footnote 1 In a similar fashion, one could view the postwar experiences of overseas Vietnamese to have consisted of multiple diasporic formations, if not multiple diasporas. Most communities in Australia, Western Europe, and North America were begun by refugees from the former Republic of Vietnam (RVN). They joined an earlier and smaller number of Vietnamese who migrated to France during the 1950s or earlier. During the Cold War and under bilateral agreements, thousands of Vietnamese, mostly from the North, traveled to the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and East Germany for study, training, and labor. Many stayed on after their contracts were over, especially after 1989, or returned to help form communities there. In addition, there were Vietnamese who went to other Asian countries, both before and after 1975, such as Cambodia, China, Thailand, and the Philippines. Closer to the present were a number of Vietnamese, mostly women, who migrated to South Korea and Taiwan for marriage. The Vietnamese diaspora has never been simple or static. This point is especially true about the postwar era, whose alterations reflect twentieth-century experiences of national division, warfare, and postwar developments.

This chapter privileges the history of diasporic formation that originated from the fall of Saigon, especially among the refugees and immigrants in the United States.Footnote 2 Vietnamese who left the South in 1975 and the years following shared a cultural and political identity with the defunct RVN, and they created the largest portions of the Vietnamese diaspora today. Having resettled in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Western Europe, they constructed an exilic identity during the 1970s and 1980s, before legal immigration from the late 1980s on led to the formation of a more transnational identity. Though not the same, these identities were shaped by the shock of the fall of Saigon, and then by a series of aftershocks caused by postwar policies and developments.

A Diaspora Born Out of Loss and Separation

In the annals of diasporic history, the fall of Saigon continues to stand as the single most dramatic and consequential event. The end of the war brought national reunification and jubilation for the victorious side – and shock and sorrow to Vietnamese whose political allegiance had been to the RVN. The different emotions were heightened by the fact that the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) had planned for a two-year campaign, but total victory came after merely four and a half months. Since the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) had successfully repelled the Easter Offensive in 1972, the RVN had reasons to think that it could withstand another “invasion” across the demilitarized zone (DMZ). As a result, the ARVN’s rapid retreat from the Central Highlands in March 1975 produced a big shock among anticommunists that led to an even greater shock when the PAVN entered Saigon unopposed at the end of April.

Unconditional surrender on the part of the Saigon regime contributed to the numb humiliation among Vietnamese anticommunists. Having fought the communists for years, a few ARVN officers took their own lives in the last days of the Southern republic rather than flee from or surrender to them. Others, soldiers and officers alike, hastened to hide or destroy material evidence of their identity. One officer, for example, forced himself to burn “papers and correspondence with the US Embassy, letters from [ARVN] generals … and letters from [Henry] Cabot Lodge and [Ellsworth] Bunker.” He also got rid of his pistol, rifle, hundreds of bullets, and the field telephone.Footnote 3 From this perspective, the iconic photographs and videos of the helicopter on top of the compound next to the US Embassy (but not the embassy itself, as was often assumed) are deceptive, because they show a seemingly orderly line of Vietnamese getting on the helicopter. Better and more accurate representations would be photographs of military boots and fatigues that South Vietnamese soldiers hastily discarded on streets and highways as PAVN tanks advanced into Saigon. Many threw away their guns and ammunition into rivers, while others destroyed documents kept in offices and private residences. The rush to self-erasure of identity happened out of fear that the communists would begin a bloodbath of reprisals against former enemies. Not being able to leave the country by air or ship, some families even abandoned their homes, left town altogether, and moved to a different city or province to avoid detection and arrest due to their association with the RVN. A woman officer, for instance, moved from Đà Nẵng to the more rural area of Hố Nai to join a small resistance group. A few months later, however, she was arrested by the security police, who secretly tailed her sister from Đà Nẵng to Hố Nai.Footnote 4

The fall of the noncommunist RVN also doubled as national loss. Its loyalists had not believed the communists to be legitimate holders of the nationalist mantle. In their eyes, Hanoi’s total victory amounted to a foreign invasion and the erasure of the real postcolonial Vietnamese nation. The shock over national loss led them to place the blame on multiple people. The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV, the successor to the wartime Vietnamese Workers’ Party [VWP]) was the biggest target, but they also blamed Vietnamese neutralists who might have directly or indirectly supported the communists. They believed that corruption and disunity among the RVN government and the ARVN leadership were among the leading causes of Saigon’s fall. Last but not least, they cast resentful criticism on the United States for having abandoned South Vietnam during the dark months of March and April 1975.

The grief over national loss was coupled with the pain of family separation. Amidst the chaos of war’s end, the majority of Vietnamese refugees departed without their families intact. They found the way to safety on the evacuation fleet of the US Navy by means of helicopters, fixed-wing aircraft, ships, and boats. Operation New Life took about 85 percent of some 125,000 Vietnamese to Guam. The island became an overnight and giant center for processing the “evacuees” and “parolees,” as the refugees were technically classified, for entry into the United States. Most were later transported to four other camps in the continental United States for a final round of processing – Camp Pendleton in California, Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania, Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, and Elgin Air Force Base in Florida – that led to the resettlement of all refugees by the end of the year. The US government called for local sponsorship, while hoping to avoid overburdening any particular community. As a result, the refugees were scattered throughout the vast country, including in medium-sized cities with few Asians, such as Fort Smith, Arkansas and Lincoln, Nebraska, that nonetheless received them in the dozens or hundreds. Final resettlement alleviated uncertainty. Yet it compounded the experience of separation as they moved from tens of thousands of fellow Vietnamese in a camp to a community with a very small presence of their coethnics.

Separation was exacerbated by the difficulty in communicating with loved ones in Vietnam. So sharp were the pain and guilt for over 1,500 refugees in Guam that they demanded to be sent back to Vietnam. Upon their return in October 1975, the Vietnamese government arrested the repatriates and accused them of collaboration with the American enemy: an act that confirmed the anticommunist belief among the majority of the refugees. Such news merely reinforced their belief about the foreignness of the communists and worsened the anguish over separation. “It has been 365 days since the day of national loss,” wrote a refugee from California, “[today we are] silent because we remember our wives, husbands, children, fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters, grandchildren, extended relatives, friends, and neighbors on our old street.”Footnote 5 “Cry a river,” goes the lyrics of a popular song written and recorded in the diaspora a few years after the war, “I have cried a river, a long river / Missing father, missing mother, missing brother, missing sister.”Footnote 6 Even after letters and packages from the United States and elsewhere were allowed to enter Vietnam, diasporic periodicals were replete with ads looking for family members, relatives, neighbors, and friends. Most ads showed a name, age, and an address, but some revealed the double pain of separation and national loss. “Military friends,” reads one in typically tiny print, “who left on the boat from Rạch Giá to Thailand on April 30, 1975, contact NGUYỄN XUÂN PHAN PO Box 154, Plymouth FL 32768.”Footnote 7

The anguish over Saigon’s fall was only the first in a series of sorrows among the emergent diasporic communities. As the refugees adapted to new societies, they simultaneously dealt, if indirectly, with postwar developments that proved exceedingly difficult for families of Southern Vietnamese with important political and military positions in the former regime. During the first year of national reunification, the Vietnamese government rounded up tens of thousands of ARVN officers and RVN officials and sent them to “reeducation camps” set up throughout the country. The incarceration came partially from the government’s fear of rebellion among the South Vietnamese and partially from a belief that it could reshape the political orientation among the losers. For the prisoners and their families, however, it was a combination of vengeful violence, violation of human rights, and international communist ideology over Vietnamese nationalism. Economic, political, and educational discrimination against the family members of the incarcerated further exacerbated the experience of incarceration. In their experience, antibourgeois campaigns and the creation of “New Economic Zones” (NEZs, vùng kinh tế mới) were punitive, while the prohibition on and destruction of South Vietnamese cultural productions and artifacts meant further erasure of their postcolonial identities. These reasons and others, including policies against ethnic Chinese after the Third Indochina War, led to the exodus of “boat people” that began in the late 1970s and lasted well into the early 1990s.

The experience of loss and separation also translated into an experience of dislocation, especially during the 1970s. In the United States, whose policy sought not to burden local governments, approximately 125,000 Vietnamese were dispersed across the country, including states with few Asian Americans, such as Arkansas, Connecticut, and the Dakotas, as previously indicated. Geographical isolation, however, proved too difficult, and many moved within a few years to areas with a larger number of Vietnamese. Climate also played a large role. Many refugees who came to the upper Midwest and New England remained there, some to this day. Others, however, relocated to warmer states. Friends and relatives, even distant ones, proved crucial for relocation. A short phone call could be enough to convince a refugee to move to California, Louisiana, Texas, or northern Virginia. The refugees in those states would have hosted their friends and relatives in their houses or apartments for a short time before the newcomers found work and a place of their own. This pattern of relocation continued upon the arrival of the boat-people refugees, who brought a critical mass to and solidified the existence of a number of diasporic communities by the 1980s.Footnote 8

How did Vietnamese refugees deal with national loss and family separation? Of utmost importance was the preservation of South Vietnamese culture in alien lands. Contrary to the trope that immigrants came to the United States with only the clothes they were wearing, some refugees brought with them books and records of popular music published and produced in republican Saigon. Copies of these books and cassette tapes were reprinted and then sold by mail by refugee entrepreneurs from places as varied as Fort Smith, Arkansas; Los Alamitos, California; Tacoma, Washington; and Ramer, Tennessee (whose population numbered fewer than 400 souls in 1975). The reproductions gave a measure of comfort over the lost noncommunist culture – a situation heightened by news about the postwar confiscation of South Vietnamese books, periodicals, and records of popular music, and, more generally, a prohibition on “decadent” bourgeois lifestyles by the new communist masters of the region below the 17th parallel. The refugees were hungry for regular reminders of the culture and political system that they had lost. “Please make an effort,” wrote a subscriber to Vӑn nghệ Tiền Phong from Montreal, “to print a photograph of Vietnam (color is best but black-and-white is fine) on the front cover [of each issue] and a song on the back cover.”Footnote 9

In the first decade alone of their exile, the refugees produced dozens of periodicals of varying frequencies, subscriptions, and durations. Upon arrival at the four aforementioned processing camps on American shores, they began writing, typing, printing, and circulating newsletters. Not long after sponsored resettlement, they began to churn out dozens of newsletters, magazines, and even dailies, such as Người Việt (Vietnamese People) in southern California, still published today. In comparison with reprints of South Vietnamese works, there were fewer new books at first. But many more were published during the 1980s. The refugee press was most prominent in the United States and Canada, but publications also came from Western Europe, Australia, and even Japan. The continuity of a noncommunist nationalism formed the most prominent political discourse in most publications, including those created by the more youthful refugees. “[We] seek among students,” states the annual magazine of an association of community college students in southern California, “the goal of preserving and developing a nationalist culture.”Footnote 10

The nationalist discourse enhanced the theme of exile (lưu đầy), and exilism dominated the refugee press and music production for at least ten years after the fall of Saigon. At Fort Indiantown Gap, the government-sponsored newsletter was called New Land (Đất Mới). It was, however, the old country rather than a new society toward which the readers were oriented. “We travel on the road of temporary exile,” open the lyrics of a song written by Phạm Duy, probably the most prominent musician in South Vietnam.Footnote 11 The exilic identity sharpened as the refugees learned more about reeducation camps, political discrimination, and antibourgeois cultural and economic policies against their friends and families in postwar Vietnam. Early refugee songs already alluded to incarceration. “I’m sending father a few sleeping pills,” go the lyrics of the songwriter and singer Việt Dzũng, “so he could sleep while in prison for life.”Footnote 12 By the early 1980s, the reality of postwar incarceration was well embedded in the consciousness of the refugees. It contributed to support among many refugees for a homeland liberation movement begun by a small number of former ARVN members then living in the United States.

The center of this movement was the United National Front for the Liberation of Vietnam (Mặt Trận Quốc Gia Thống Nhất Giải Phóng Việt Nam). Its headliner was Hoàng Cơ Minh, a former commodore in the South Vietnamese Navy, who now led dozens or, possibly, hundreds of young soldiers at several camps along the borders of Thailand and Laos. Active mostly until 1987, when Minh committed suicide during pursuit by the Laotian military, the Front received support among many Vietnamese in the diaspora, especially in the United States and France. Today, it is remembered for alleged fraud and, possibly, the assassination of refugee journalists who were critical of its fundraising and other activities. Behind this organizational history, still incomplete in the telling, is a larger and deeper story about the longing for homeland among the refugees. Rooted in the sudden loss of the RVN and the harsh postwar experiences, this longing led some refugees to such an illogical and illusionary hope about reunion with their loved ones that they lent monetary support to the Front in blind faith.

The homeland liberation movement had ceased by the late 1980s, when legal immigration began en masse and eased the pain of separation. Still, it was not until the end of the Cold War that diasporic anticommunists accepted the futility of force to retake the homeland. They gave up the illusionary dream and turned instead to the hope that Vietnamese within the country would create and support dissident movements, similar to those in Eastern Europe, to bring down the CPV in the end and bring forth democracy to the country. Time did not completely heal the anguish of national loss, but it offered new perspectives more suited to the realities on the ground.

Diasporic Identity Amidst Vietnamese Erasure and American Indifference

During the 1970s and 1980s, refugee communities were occupied with economic survival: work, education, and supporting people in Vietnam with remittances and gift packages of consumer products. Most engaged in manual labor, at least at first. On the US Gulf Coast, especially, refugees from coastal towns and villages in Vietnam were pursuing fishing and shrimping. In Arkansas, many worked at chicken-processing factories. Whatever their line of work, they recognized that social mobility in the United States was achievable through higher education, especially in the science and technology fields. Many planned accordingly for themselves and, above all, their children. For themselves, they sought vocational and associate degrees to become technicians and engineers at tech companies and factories. They promoted and demanded studiousness among children as a duty to their families and to the Vietnamese people. Newspapers and magazines frequently highlighted the academic achievements of high school and college students, especially news of scholarships and graduations with honor. Even refugees who engaged in manual labor, factory work, or small businesses hoped that their children would earn a college degree followed by a job with a stable income at a company, a corporation, or a hospital. Without knowing the earlier history of Asians in the United States, the refugees pursued a strategy that echoed and, unwittingly, contributed to the “model minority” stereotype that had entered the mainstream during the 1960s.

Economic survival and educational pursuit left only a small amount of time for socialization and community organization. Nonetheless, refugee communities quickly constructed their own spaces for networking and preserving their cultural and political values. In large communities and even some small ones, young adults were tasked with teaching Vietnamese to children one or more hours each weekend. In large communities, former leaders of the Boy Scouts created a local chapter that duplicated the tradition of the Boy Scouts in South Vietnam. Given the great distances in North America, travel and even phone calls were costly. As a result, refugees mailed many letters across the diaspora, and continued to churn out newsletters and periodicals as the main means of communication. The principal concern among those periodicals was twofold: condemning the foreignness of the communist system and fighting to retain Vietnamese traditions while living in very different societies.

They also sought to retain it in other forms. The production of popular music on cassette tape often featured romantic songs from South Vietnam. Then, the company Thúy Nga began producing the cabaret-style and direct-to-video series Paris by Night in 1983. Showcasing new songs, as well as classics, from South Vietnam, the series quickly became the best-known entertainment program in the diaspora. Its copies were bootlegged and pirated in Vietnam, partially for the dazzle of staging and production, and partially because the songs were banned by the government. In this respect, the series was a primary contributor to keeping alive the musical tradition in the RVN, including memories of republican Saigon in particular and South Vietnamese noncommunist nationalism in general. Reflecting the diasporic dominance of the refugee generation in the United States, Thúy Nga relocated its headquarters from France to southern California by the end of the 1980s.

Religious organizations were also active in combining faith practices and the anticommunist and nationalist ideology. This phenomenon occurred among Buddhists, Caodaists, Protestants, and, especially, Catholics. Having left Vietnam in huge numbers, Catholic refugees were privileged by initial access to the local and national resources of the Catholic Church in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Western Europe. They further fell back on their tradition to organize their communities for worship, association, and other purposes. As early as May 1975, some 7,000 refugees at the temporary refugee camp Fort Chaffee held a procession honoring a statue called Our Lady of Vietnam the Refugee. Eventually resettled in New Orleans, this statue became a local object of devotion and was occasionally flown to other communities for similar processions. Pilgrimages, too, constituted a combination of religious devotion and political affirmation. The Catholic community in Portland, for example, was led by a Redemptorist priest who had come to the United States two years earlier for studies. Along with a refugee priest from Washington State, he sought permission for the use of the Grotto, a major Marian shrine in the Portland area, for a pilgrimage during the July Fourth weekend in 1976. This regional festival drew Catholic refugees from throughout the Northwest and became an annual event until temporary interruption because of the Covid pandemic in 2020. Larger was the national Marian pilgrimage to Carthage, Missouri organized by the Congregation of Mother Co-Redemptrix (CMC) that originated in northern Vietnam. Begun in the summer of 1978 with about 1,500 pilgrims for an overnight event, this pilgrimage has grown to an annual festival running for four days with the participation of tens of thousands of people. Central to this pilgrimage was highly anticommunist devotion to Our Lady of Fatima that the CMC had promoted since its humble beginnings in the late 1940s. In addition, the 1983 pilgrimage witnessed the dedication of an outdoor 34ft statue of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child while reaching to a Vietnamese refugee. It was among the first major diasporic public artworks to commemorate the postwar experience.

At the secular level, the early refugee communities might not have had enough resources for large-scale activities, but they made sure to organize an annual celebration of the lunar New Year (Tết). This celebration typically included Vietnamese food, homegrown entertainment, and áo dài pageants among young women. Members of a large community might also gather during springtime to honor the Hùng Kings, or during the fall to celebrate children with the mid-autumn festival. Over time, these smaller festivities tended to fade away, owing to the constraints of time and the greater attention paid to the organization of Tết celebrations. These festivities received the backing of all groups of people, but their organization and execution often depended on university students, who possessed a critical mass and the energy to put together an entertainments program, and they also had institutional access to help lower the organizational cost. In the largest diasporic community of Orange County, California, students not only have organized the Tết festival since 1982, but also expanded it from one to two weekends.

A different annual event that only grew in significance was the commemoration of Black April (Tháng Tư Đen). The commemoration occurred across large and small communities alike and became a core symbol of the refugees’ political identity. Centered around the fall of Saigon, it offered the refugees a collective and ritualized articulation of grief over loss and separation. From the late 1970s, when boat people began to arrive in the United States and other countries in large numbers, Black April gradually took on more meanings that reflected the experience of political repression and economic poverty in postwar Vietnam. The refugees began to shift their interpretation of Saigon’s fall as partially a result of American abandonment and poor RVN and ARVN leadership, emphasizing instead the cruelty of the postwar political system and the persistent violation of human rights on the part of the CPV. The exodus of boat people, including the death and suffering during the dangerous journeys, became as much a shared experience as it was a political rallying point in the postwar anticommunist critique.

The postwar critique targeted the Vietnamese government, but, arguably, it was also a reaction to the lack of representation of South Vietnam in many Western countries. This situation was not universal. In particular, the Australian government was more attentive to the history of its involvement with the ARVN and even allowed former South Vietnamese officers to apply for veteran benefits. There were no parallel programs in the United States, and national and local commemorations focused squarely on the American experience, giving little space to their erstwhile allies. While many Americans were sympathetic to the plight of the refugees in 1975 and thereafter, they viewed the former South Vietnamese as, at best, victims of communism rather than autonomous agents of their own – or, at worst, as a burden on the US economy during the 1970s and 1980s. In the meantime, heavily American-centric interpretations of South Vietnam did little to alter the dominant wartime perspectives of the RVN and ARVN as weak, corrupt, and unworthy of US largesse.

Most prominent among those interpretations were the PBS series Vietnam: A Television History (1983) and the journalist Stanley Karnow’s tie-in book Vietnam: A History, whose coverage of the South Vietnamese focuses on their helplessness and corruption. The series shows the South Vietnamese in cities primarily as victims or survivors, and, in the case of ARVN soldiers, young men who searched the pockets of dead civilians for change during the Tet Offensive. For every few seconds of footage showing urban Boy Scouts, there would be half a minute about bargirls and refugees. In Hollywood movies of the 1980s, noncommunist South Vietnamese typically appeared as peripheral or stock characters: prostitutes, pickpockets, pimps, drug addicts, and, again, people on the receiving ends of American largesse. When given more time on the screen, like the principal Vietnamese character in the comedy Good Morning, Vietnam, they would turn out to be members of the National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) in disguise. On stage, they appeared in the London and Broadway hit Miss Saigon as exploitative pimps, pathetic prostitutes, and pitiable refugees. Besides the erasure of their history in a unified Vietnam, refugees in the United States found a considerable level of ignorance and distortion about their history within the country of their resettlement.

Yet it was during the 1980s that the refugees had more positive views of the US government and society. The main reason for this reappraisal was the worsening economic and political situation in Vietnam, which provided a prism of contrasts to the experience in North America. An additional reason was renewed moral force stemming from the anticommunist rhetoric of the administration of US President Ronald Reagan. The papacy of Pope John Paul II, who hailed from a communist country, offered another affirmation of their anticommunist ideology. Similar to Americans on the right, a growing number of refugees took the blame for losing the war from the White House and placed it instead on the US Congress and the media. This reaction was partially a result of their wariness toward the media after the unfavorable and shallow characterization of the South Vietnamese government and society on television. It was further amplified as a strong conservative ethos returned to American politics. Lastly, global events in the late 1980s and the early 1990s led to the end of the Cold War and a corresponding triumphalism, which confirmed and empowered political attitudes among the refugees.

The Immigrant Generation and the Shift to a Transnational Identity

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the majority of former refugees had become citizens of the countries of their resettlement by the early 1990s. Motivated by opportunities for social mobility and a patriotic ethos, some of the 1.5- and second-generation members also joined the armed forces in their countries of resettlement. Such outcomes resulted in a more hybrid identity: Vietnamese American, Vietnamese Australian, Vietnamese German, and so on. As families were reunited through legal migration in the 1990s, the exilic identity of the former refugees began to give way to a transnational identity of naturalized citizens who retained some ties with, and returned to visit, the homeland. They continued to celebrate Tết and commemorate Black April each year. Yet now they were endowed with a hybrid and Vietnamese American identity when celebrating the former, and they turned the latter into a remembrance of the difficult postwar experience, as well as the beginning of their lives in an adopted country. In recent years, a Black April ceremony might still include reading aloud the names of ARVN leaders who killed themselves rather than surrender during the fall of Saigon. Yet more often, speeches and music during the ceremony have evoked the deaths of people who escaped by boat, or the incarceration of former officials and officers in reeducation camps. The loss of the Southern republic in 1975 remains the starting point, but it has served as the background to postwar remembrances in the foreground.

Changes in Black April commemoration reflect a broader shift from the refugee generation of the 1970s and 1980s to the influx of immigrants from the late 1980s up to the present. The final era of the Cold War coincided with the beginning of a new and consequential era of Vietnamese immigration to the United States. Starting in the late 1980s and especially during the first half of the 1990s, tens of thousands of Vietnamese came to the United States through one or other form of legal migration. Some came under the Orderly Departure Program (ODP) created by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The ODP enabled many to migrate as former employees of the United States or under the category of family reunification. Most notable was the Humanitarian Operation Agreement of 1989, commonly called “the HO” among Vietnamese, which allowed the legal migration of tens of thousands of former political prisoners and their families to the United States. Having followed the postwar situation closely, the refugees, especially a group of women in northern Virginia, were crucial in the advocacy for this migration well before the program was formally established. In addition, there were thousands of Amerasians and family members on their mothers’ side, who came after Congress passed the Amerasian Homecoming Act. The beginning of this mass migration eventually led to the presence of an estimated 1.4 million Vietnam-born people in the United States in the early 2020s.

The influx of immigrants during the 1990s and 2000s substantially altered demographic, economic, and cultural lives in the Vietnamese diaspora. Because fathers and oldest sons tended to be the first in their families to escape by boat, there had been a shortage of marriageable women in comparison with single men. Legal migration offered a solution to this issue, because it brought many single women to the United States and, consequently, many more marital unions among the coethnics in the 1990s. For single and divorced people, especially men, visits to the homeland might also lead to meeting potential partners for marriage. Already desiring to make up for having no opportunities in postwar Vietnam, the new arrivals were highly motivated by the economic boom of the 1990s. Taking after the refugee generation, the immigrants emphasized education as the primary vehicle of social mobility. They placed heavy expectations on their children’s performance in high school and college, and invested especially in preparation for careers in health care, engineering, and, to a lesser degree, business. By the 2000s, when many former 1.5-generation refugees began having school-age children of their own, the immigrants and former refugees began adopting the educational strategies of immigrants from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea, and invested in private and after-school tutoring for their children in K-12. Although their history diverged significantly from the histories of these other groups, they have increasingly interpreted the identity of their children in the broader category of “Asian” in addition to “Vietnamese.”

Conversely, a number of immigrants, especially women, entered the nail industry, which had drawn a small number of refugees to California since the 1970s. Similar to the restaurant industry, the nail industry is service-oriented without requiring a high level of oral communication. Thanks mainly to the influx of immigrants, Vietnamese now make up over 40 percent of manicurists in the United States and an astounding 80 percent in California. Except for New York City, whose market is dominated by Korean and Chinese manicurists, there are currently more Vietnamese manicurists than any other ethnic group in virtually all major urban areas. And they have been willing to bring their trade to far-flung towns and cities. Indeed, this occupational concentration has led to a return of the Vietnamese presence in areas that had received refugees in 1975 only to see them move to states that were warmer or had more Vietnamese. Instead of ads looking for relatives and friends, now immigrant salon owners place ads in California and Texas looking for workers willing to relocate for a few years to states with a small Asian population, such as Alabama, Indiana, Maine, and the Dakotas. “Needing female and interstate manicurists with experience,” reads a typical ad, “high tip, high salary, comfortable living space [provided], $800/week winter, $1200/week summer.”Footnote 13 The immigrants have done what the US government could not do in dispersing the refugees across the country. This interstate migration has led to the intra-ethnic saying that if anyone is traveling through a remote town and wishes to speak Vietnamese, the best bet is to find a local nail salon. This occupational dominance has extended well beyond the borders of the United States, as a growing number of Vietnamese have become manicurists in Australia and Europe, especially the UK.

The immigrant influx also brought to American shores a new slate of singers and performers who had been born during the Vietnam War but did not have opportunities for professional advancement in the Vietnamese music industry. They were recruited by Paris by Night and a competing series produced by the company Asia Entertainment, both headquartered in the Little Saigon community of Orange County, California – the largest in the world outside of Vietnam. When not recording for these series, they traveled to perform at live shows across North America, Australia, and Europe. Still, the two series were crucial to cultural life across the diaspora. Between 1991 and 2016 they revived hundreds of South Vietnamese popular songs, which were performed on larger stages and given glossier production qualities. A number of shows were programmed to honor particular South Vietnamese and diasporic songwriters. Some shows were organized around themes commemorating the RVN and, especially, the ARVN. The latter emphasis was a response to the humiliation in reeducation camps and the continual erasure of noncommunist South Vietnam. In addition, music companies produced hundreds of new records that were distributed in CD format. Communication entrepreneurs in Orange County also established several television stations that broadcast news and entertainment to the diaspora at large. In the religious realm, Buddhist, Cao Đài, and Christian communities saw a rise in membership that translated into the construction of many new temples and churches, especially during the 2000s. Besides worship, these religious sites have provided diasporic singers a distinctly ethnic space for live performance during festivals and celebrations.

The broad shift in the immigrant generation does not mean that former refugees were no longer active after the early 1990s. Many remained closely involved in political and cultural organizations at the local, national, and transnational levels. Nonetheless, the new arrivals provided an immediate and powerful injection of economic and political energy into Little Saigon communities. Since the refugees had established many professional and other ties, the new arrivals not only came into readymade networks, but also created new ones, such as associations of former political prisoners, alumni of South Vietnamese educational and military institutions, and former members of a Buddhist temple or a Catholic parish in the homeland. They often coordinated regional and national gatherings and activities, especially anticommunist protests. Many immigrants had been incarcerated in reeducation camps or were family members of the incarcerated. The rawness and bitterness of their postwar experience led them to be in the forefront of opposition against the Vietnamese government in various Little Saigon communities. This activism included protests against cultural and entertainment events with participants from Vietnam, and even against ethnic businesses whom they believed to have benefited from dealings with the Vietnam government. They vigorously, if futilely, opposed US rapprochement with Vietnam, including the lifting of the American embargo against the communist government.

It is misleading, however, to suggest that the activism of the immigrant generation was confined to anticommunist protests. For one thing, the immigrants were limited in political and diplomatic capital in the 1990s. In no substantial way could they affect the momentum of US–Vietnamese rapprochement, especially since John McCain, whom they revered on account of his crucial role in the HO program as well as his wartime imprisonment, was a leading advocate of rapprochement. Notwithstanding the energy that they put into antirapprochement discourse, they recognized the limits of their action. More importantly, they actively participated in the fundraising for and construction of memorials, statues, museums, libraries, publications, and other forms of historical preservation about the experiences in South Vietnam and the postwar era. Not surprisingly, veterans were especially interested in Vietnam War memorials that represent the ARVN, while former refugees gathered popular support for boat-people memorials. As a result, the 2000s and 2010s witnessed an array of new war and boat-people memorials across the United States, Canada, Australia, and Western Europe, especially Germany. A small number of former refugees returned to the original sites of camps in Indonesia and Malaysia to visit the graves of people who died there. Over the diplomatic objections of the Vietnamese government, they erected memorials of their exodus.Footnote 14 Lastly, many immigrants have seized upon the Internet and social media for an alternative historical record to official Vietnamese representations of South Vietnam and the diaspora.

It is here that we should note the diasporic significance of the flag of the RVN, which, to the surprise of television spectators worldwide, was seen during the rally-turned-riot at the US Capitol on January 6, 2021. During the 1970s and 1980s, the aforementioned erasure in Vietnam and indifference in the United States contributed to the confinement of this flag largely within the refugee communities. Although it occasionally appeared at events outside of the ethnic communities, such as at protests against the violation of human rights in communist countries, the flag was visible mostly in Vietnamese households and businesses, and at annual events. After the arrival of immigrants in the 1990s, however, the flag became ubiquitous in Little Saigon communities. It appeared not only at anticommunist protests, Tết gatherings, and parades, but also at fundraisers, concerts, reunions, and funerals. More significantly, its visibility outside of the ethnic communities grew enormously. It has shown up at nonethnic events such as interracial religious ceremonies, and local and regional parades. It has appeared at city halls, community centers, schools, parks, and other public spaces. A number of municipal governments have recognized the flag as a symbol of Vietnamese American identity. One outcome is that its meaning has shifted from representing the lost state of the RVN to a representation of the postwar experience. Many second-generation Vietnamese, especially those from large communities, have come to view it as the “heritage” or “freedom” flag.

Notably, the meanings of freedom among Vietnamese refugees and immigrants were shaped not so much by American ideas but, again, by postwar developments. For both the refugee and immigrant generations, freedom is the opposite of the postwar incarceration, repression, and poverty that they had experienced or, among 1975 refugees, learned from their loved ones. In this respect, the fall of Saigon was not the end but the beginning – and postwar developments were a series of aftershocks after the fall of Saigon. Because the aftershocks went on for years, they were in some respects more consequential than the demise of the RVN. “Were it not for the HO program,” reflected a former reeducation camp detainee, “[my] corpse might have been underground due to tuberculosis contracted during Communist imprisonment.”Footnote 15 In contrast, the refugees and immigrants experienced material abundance and social mobility in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, and, especially, the United States. “If my grandchildren,” said the mother of an immigrant to the United States in the 1990s, “could have received a proper education, if my child could have been a teacher with a proper wage, if her husband could have lived free … then I’d never have let them leave.”Footnote 16 The immigrants came to a universalist belief about freedom on the basis of their visceral and searing postwar experiences.

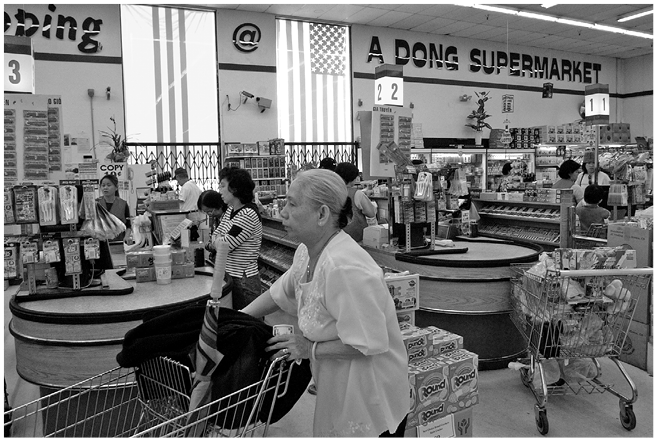

Figure 22.1 A Dong supermarket in Westminster’s Little Saigon with a former South Vietnamese flag and an American flag draped over the front windows (May 12, 2004).

This universalist belief has informed their relationship with the homeland, as many diasporic Vietnamese have maintained a highly critical attitude toward the monopoly of political power by the CPV. Yet this relationship has evolved beyond anticommunist protests in Little Saigons. It began in the 1990s when Vietnam’s entry into the global market made it easier for Việt kiều, or overseas Vietnamese, to visit Vietnam and invest in business. Some elderly Vietnamese, including the songwriter Phạm Duy in 2005, have returned permanently to the homeland. The government has allowed most music from South Vietnam, including previously sensitive “soldier music” (nhạc lính), to be recorded and performed, and many diasporic singers have performed in Vietnam, while some Vietnamese singers have done the same in the diaspora, including the United States. Many diasporic television stations, perhaps most, have included entertainment and even news programs from the homeland in their daily broadcast. For decades now, Vietnamese publishers have reissued new editions of works by South Vietnamese authors. Catholic priests and Buddhist monks, meanwhile, have utilized religious networks and traveled abroad to raise funds for organizations in Vietnam. Conversely, Vietnamese in the diaspora have raised money to aid in natural disasters and other charitable activities in the homeland.

Conclusion

Other Vietnamese diasporic formations, including those in central and eastern European countries, followed very different trajectories.Footnote 17 A treatment of the entire diaspora is difficult to achieve at this time. Nonetheless, we can affirm that these trajectories reflect the multiplicity of Vietnamese history, which has included different visions for a postcolonial nation, divergent state formations, and enormous warfare between Vietnamese and foreigners, as well as warfare among Vietnamese. The history of the diaspora is inextricably rooted in the history of modern Vietnam itself.

Moreover, any convergences among different parts of this diaspora in the present and future would likely depend on developments within Vietnam, including its relationship with its powerful neighbor to the north. The last twenty years have seen a growth in anti-Chinese protests organized by immigrants in communities across the diaspora, not only in those that originated from refugees after the fall of Saigon. People from different parts of Europe have even joined one another on occasion, under different flags or no flags at all, to protest against China’s military and economic activities regarding the Paracel and Spratly Islands. As diasporic Vietnamese, especially first-generation immigrants, continue to adapt and adjust to the societies of their resettlement, there are yet signs that their nationalist belief has significantly diminished. As many have been naturalized in another country, they remain interested in the affairs of Vietnam while inserting their own interpretations of war and postwar experiences into the public sphere whenever possible.