INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am humbled and honored to be standing before you as the recipient of the 2018 John Gaus Award from the prestigious American Political Science Association. I’d like to first thank my nominators, Rosemary O’Leary and Tony Bertelli; thank you for your continued colleagueship and friendship. I’d also like to thank the selection committee, Kelly Leroux, chair, Jill Nicholson-Crotty, and Andy Whitford. In addition, there are a number of people here who have been colleagues, mentors, friends, and even deans, who have been instrumental in my career and I’d like to thank them: David Rosenbloom, Frank Thompson, Carolyn Ban, my current Dean Charles Menifield, and my former Dean Marc Holzer. I’d also like to thank Beryl Radin, a senior woman in the field, who has been very gracious and generous with her time and advice.

IN THE BEGINNING

It is a somewhat circuitous path that leads me here today, in that the people I was living with when I was in high school didn’t intend for me to go to college, despite my protestations to the contrary. By the time I finished high school and I left there and Connecticut, college was not even on my radar screen. Long story short, I ended up in Miami, Florida after graduating high school, and started working as a bookkeeper for the Dobbs House at the Miami International Airport. Dobbs ran airport restaurants and was a US airline food caterer at the time and I was very good with numbers. In the first year that I was at Dobbs, I trained two persons, both men who were white, to be my supervisor. And shortly thereafter, a young MBA grad was hired to run the operations in our unit at the airport. And one of the first things he did was fire anyone over 50 years of age, and anyone who was black or brown, notwithstanding their age. I knew we had a civil rights law, but I just knew instinctively that this was wrong. These were the values instilled in me by my beloved parents. They taught me right from wrong and that treating people differently because of their race, color, or religion was just plain wrong. [We didn’t talk about gender as much, because my maternal and paternal grandmothers were the matriarchs of our roost.]

So, I confronted him about his actions, and I was promptly fired (it is the first and only time I was fired from any job), and it was at this moment I decided it was time for me to go to college. I mention this experience because it touched upon one issue that would draw me to the field of public administration. I always believed that government had a responsibility to address social problems and bring about positive change. And this certainly fits the tradition of John Gaus, who in his book, Reflections on Public Administration (1947), recounts how crises as well as changes in people, place, technology, and philosophy in the first half of the 20th century led citizens in the US to repeatedly to look to government for relief.

Norma M. Riccucci, Board of Governors Distinguished Professor in the School of Public Affairs and Administration at Rutgers University, delivers her John Gaus Award Lecture titled “On Our Journey to Achieving Social Equity: The Hits and Misses” at the 2018 APSA Annual Meeting.

I started out taking liberal education courses at Miami Dade community college before I transferred to Florida International University. And it was there that a political science professor introduced me to public administration. I asked him, “What exactly is public administration,” and his response was the typical one we rely on when we respond to family and friends who ask us the same question: “It’s similar to a business administration degree but only in government.” It wasn’t until years later that I attempted to pull together how I defined public administration, which resulted in my logic of inquiry book, Public Administration: Traditions of Inquiry and Philosophies of Knowledge (2010).

I earned a bachelor’s of public administration and it was in this program that I first read about something called the “New Public Administration.” It was only textbook coverage, however, so it was very cursory. It was in the first edition of Nick Henry’s Public Administration and Public Affairs (1975), which I still have on my bookshelf. And, it doesn’t even refer to social equity, which would become a central focus of my research. Rather, Henry (1975, 28) writes that:

The focus is disinclined to examine such traditional phenomena as efficiency, effectiveness, budgeting, and administrative techniques. Conversely, the New Public Administration is very much aware of normative theory, philosophy, and activism. The questions it raises deal with values, ethics… and the broad problems of urbanism, technology, and violence. If there is an overriding tone to The New Public Administration, it is a moral tone.

I wanted to learn more about the New Public Administration, so I went to the card catalogue at the FIU library and looked for the book referenced by Henry: Frank Marini’s (1971) Toward a New Public Administration: The Minnowbrook Perspective. Not there, but I would later return to the issues addressed by New Public Administration.

I instinctively knew as an undergrad student in public administration that I wanted to go on for a PhD in the field and focus on issues of social change. I was particularly interested in race and gender relations. My professors at FIU were graduates mostly of the Maxwell School (e.g., Ann-Marie Rizzo) and USC, and encouraged me to choose one for my MPA and the other for my PhD.

Working on my MPA at USC, I had the privilege of working with folks such as Wes Bjur and Bob Biller. I also wondered if there were any women in public administration, and was so happy to learn of Beryl Radin at USC. But, I discovered that she was at the DC campus, so it would be another 10 years before I would have the pleasure of working with her.

In my PhD program at the Maxwell School, I studied under David Rosenbloom, whose Intellectual History of Public Administration course solidified by commitment to public administration. In the PhD program, I learned of the significant contributions that George Frederickson made to the field, when he wrote his chapter in Marini’s Toward a New Public Administration. Here Frederickson (1971, 311, emphasis in original) wrote that:

The rationale for Public Administration is almost always better (more efficient or economical) management. New Public Administration adds social equity to the classic objectives and rationale. Conventional or classic Public Administration seeks to answer either of these questions: (1) How can we offer more or better services with available resources (efficiency)? or (2) How can we maintain our level of services while spending less money (economy)? New Public Administration adds this question: Does this service enhance social equity?

Defining social equity, Frederickson (1971: 311) then went on to say that the procedures of representative democracy presently operate in a way that either fails or only very gradually attempts to reverse systematic discrimination against disadvantaged minorities. Social equity, then, includes activities designed to enhance the political power and economic well being of these minorities.

Frederickson thus advanced the seminal theoretical justifications for social equity as a critical value in public administration (also see Frederickson Reference Frederickson1980; Reference Frederickson1990), indeed referring to it as the “third” pillar of the field.

The concept of social equity has since assumed a host of different meanings,Footnote 1 but it continues to center on the tenets set forth by Frederickson—fair and just treatment and the equal and equitable distribution of benefits to the society at large. As Susan Gooden (Reference Gooden2014) and Gooden and Shannon Portillo (2011) point out, social equity is fundamental to the fulfillment of democratic principles. David Rosenbloom’s Federal Equal Employment Opportunity (1977) was one of the earliest, most comprehensive books that reported on the federal government’s experiences with equal employment opportunity, which also shapes the contours of the concept of social equity.Footnote 2

Viewed collectively, social equity can thus be construed as the democratic constitutional values of fairness, justice, equal opportunity, equity, and equality (see, for example, Rosenbloom, Reference Rosenbloom1977; Jennings Reference Jennings2005). It embodies a host of concepts, legal tools, and public policies including, from the perspective of employment, equal employment opportunity, affirmative action, and diversity initiatives. The value, worth, and effectiveness of modern democratic governance particularly in a pluralistic society is inextricably linked to a diverse corps of civil servants generally, but in particular in the upper reaches of government bureaucracy. In this sense, two of the key pillars of public administration—efficiency and effectiveness—are contingent upon the strength of the third—social equity.

Some of my early work focused on the use of affirmative action, which continues to be one of the most polemical and polarizing issues over the past several decades. Some of my work here was intentionally normative, in the tradition of the New Public Administration. Scholars, practitioners, and policymakers have debated the appropriateness and potential effectiveness of affirmative action since its inception. After decades of legal wrangling and uncertainties, the US Supreme Court issued a ruling, in 2003, Grutter v. Bollinger that paved the way for not only universities but also government employers to rely on affirmative action policies in order to redress past discrimination as well as to promote or enhance diversity in the classroom and the workplace. But, the bar has been set relatively high by the Court—at least a majority of its members—and so we continue to grapple with such issues as the use of scores on tests, such as SATs, GREs, merit exams, and the weight they should be accorded in making admissions, hiring, or promotion decisions (I’ll turn to the more recent affirmative action case, Fisher v. University of Texas, later).

The first US Supreme Court decision on affirmative action, the 1978 Regents of the University of California v. Bakke case, essentially asked the question, can we set aside test scores and rely solely on race to admit students to a university or college?Footnote 3 At that time, the question of why the test scores of certain groups such as African Americans were systematically lower than that of whites was not considered. Alan Bakke claimed that his MCAT scores among other measures were higher than the persons of color admitted to the medical program; hence, Bakke concluded, less qualified persons of color were being admitted over him. In the Bakke case, the High Court, in a marvel of indecision, supported the general principle of affirmative action in admissions but struck down its use by the University of California under the Fourteenth Amendment of the US Constitution and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 because of its overwhelming reliance on race.

Today, it seems widely accepted that test scores are not perfect measures of ability, competence, or merit. But, early on, it may be recalled, tensions between merit and equity ran high. The value of merit has been particularly significant to our field in that government employers historically relied on “merit” exams to select or promote employees. Whether designed to depoliticize government service or identify “qualified” civil servants, the importance and value of merit have been clear both historically and politically. But, as the value of social equity became increasingly important, the general populace began to question the compatibility of merit and equity specifically asking, if we pursue equity, do we sacrifice merit? Many public administrationists believed that a socially diverse work force could only improve the legitimacy of government. Indeed, they saw greater quality in the delivery of government services. Lloyd Nigro (1974, 245), for example, in the first affirmative action symposium appearing in Public Administration Review argued that “to be truly effective, our public organizations must be representative in the most positive and meaningful sense of the word.” He went on to say that “representativeness is counted on to act as a sort of internal ‘thermostat’ on administrative behavior, keeping it within the boundaries set by societal values and attitudes” (Nigro 245–246).

Even Frederick Mosher (1968, 206), in his classic Democracy and the Public Service, which greatly influenced my career, stated in the first edition, published in 1968:

The ideals which gave support to merit principles were of course never fully realized. In fact, given the gross imperfection in American society and its toleration of discrimination and of a more or less permanently underprivileged minority, some of those ideals were, in part at least, mutually incompatible. The concept of equal treatment hardly squares with competitive excellence in employment when a substantial part of the population is effectively denied the opportunity and/or the motivation to compete on an equal basis through cultural and educational impoverishment.

In the second edition of his book, published in 1982, Mosher (1982, 221) returned to this issue and argued that the merit system must continually evolve in conjunction with, and ultimately to accommodate, changes in societal values. He stated that “the principles of merit and the practices whereby they were given substance are changing and must change a good deal more to remain viable in our society” (Mosher Reference Mosher1982, 221).

The real issue behind the debate, to be sure, could not be reduced to how equity was defined. Rather, the critical issue which galvanized the debate was the underlying assumptions about how equity would be achieved. That is to say, those who viewed equity as a challenge to merit simply assumed that less qualified women and people of color would be hired over better qualified white males (see, e.g., Stahl Reference Stahl1976). Importantly, though, there was very little empirical proof to substantiate this claim.

This issue of merit versus equity may be playing out in an interesting, politically-motivated manner today, as seen in the lawsuit filed by Asian Americans against Harvard University (Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard 2017; 2014).Footnote 4 Test scores or more broadly scoring systems continue to be relied upon and can be manipulated to control the desired outcome. Most universities today rely not on a single test score but rather on a battery of tests when they make admissions decisions. In its admissions’ process, Harvard scores applicants on five categories: academic, extracurricular, athletic, personal, and “overall,” which is not an average of the other criteria; it is here that an applicant’s race or ethnicity, for example, could be included. Applicants are ranked from 1 to 6, with 6 being the best. The lawsuit, which was brought by the anti-affirmative action group, Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), alleges that while Asian American applicants have strong academic records, Harvard discriminates against them by scoring them lower on personality traits. The lawsuit claims that Harvard caps the number of Asian American students by placing more weight on subjective, non-merit-based criteria in admissions.Footnote 5 Parenthetically, Edward Blum is the founder of SFFA; Blum was the driving force behind the Fisher v. University of Texas case that I will address shortly.

Under the Obama administration, the Justice Department and the Department of Education in May of 2015 decided to take no action on a similar complaint against Harvard’s admissions.Footnote 6 Under the Trump Administration, the Department of Justice led by Attorney General Jeff Sessions decided to launch the investigation into Harvard’s admissions practices to explore that same claim. [The Trump Administration also abandoned President Obama’s policy calling on universities to consider race in order to diversify their student bodies.] Many are persuasively arguing that Blum is pursuing the case to force the High Court to issue a negative ruling on affirmative action. There are also concerns that the Justice Department will use the case to argue that all race-conscious admissions are a violation of the US Constitution and Title VI Civil Rights Act. The Harvard suit alleges that the university uses race as a dominant factor in admissions and engages in “racial balancing.”Footnote 7 The lawsuit also claims that Harvard overlooks race-neutral alternatives when making admissions decisions and that in its efforts to promote diversity, it harms Asian Americans. The SFFA claims that Harvard relies on the same type of stereotyping and discrimination against Asians that it used to justify quotas to bar Jewish applicants in the 1920s and 1930s (Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard 2017; Hartocollis Reference Hartocollis2018; Lane Reference Lane2018).Footnote 8

Interestingly, Dana Takagi (Reference Takagi1998) in her book, The Retreat from Race: Asian American Admissions and Racial Politics, makes the case that universities have deliberately manipulated entrance criteria to disadvantage Asian American applicants. She points to, for example, an over reliance in some cases on athletic ability as a pivotal criterion, which early on had a negative impact on Asian American applicants. A number of universities, including Harvard, Brown, Cornell, and Princeton faced such complaints in the 1980s (The Harvard Plan 2017). In this sense, elite universities want it both ways: rely on test scores and other “specific measures” of performance when it suits their interests, but eschew them when they don’t (also see Warikoo Reference Warikoo2016).

The US district court will determine whether Harvard has discriminated against Asian Americans in admissions under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and it is possible that the case will make its way to the High Court, where Blum and the SFFA hopes to see Fisher v. University of Texas overturned. Let me briefly address that case as it provides the current legal standing on a critical social equity tool, affirmative action.

Fisher v. University of Texas

Most perceive the High Court as being neutral, with each Justice issuing an opinion or decision in a vacuum; that they operate in silos. Well, this is not the case. The High Court’s rulings are rendered through negotiations and compromises between and among the Justices. This was certainly the case in 2013 with Fisher, where the High Court was expected to strike down the race-conscious program, despite the 5–4 ruling in the 2003 Grutter v. Bollinger case, mentioned earlier.Footnote 9 Certainly the composition of the Court had changed since then, but the issue goes beyond this. In Fisher (2013) the Court did not make a substantive ruling on the use of race in admissions, but instead remanded the case to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which had upheld the use of race.Footnote 10 The Supreme Court in its 7–1 ruling instructed the Fifth Circuit to closely examine the issue of “critical mass,” which universities rely on when justifying their use of race in admissions. Although universities do not seek to admit a specific percentage of students of color, they do seek to enroll a critical mass of underrepresented students to ensure the creation of diverse learning environments, which benefit all students by producing “cross-racial understanding and the breaking down of racial stereotypes” (see Grutter 2003, 308).Footnote 11 Surprisingly, Justices Sotomayor and Breyer signed on with conservative block of the Court—Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Scalia, Alito, and Thomas, as well as the swing vote, Kennedy, even though they did not agree with the conservative Justices view that critical mass was really a façade or pretense for racial balancing, or worse “quotas.”Footnote 12 The Notorious RBG (Justice Ginsburg) not surprisingly wrote the sole dissent in Fisher opining that the affirmative action programs should be upheld, period; Justice Kagan recused herself from the case as she was Solicitor General when the Department of Justice filed an amicus curiae or friend-of-the-court brief in Fisher when the case was before the Fifth Circuit.

The well-attended lecture took place on Friday, August 31, 2018 from 6:00 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. in the Boston Marriott Copley Place in Boston, Massachusetts.

So why was there no substantive ruling in the case, and why did the liberal Justices Breyer and Sotomayor, who in her poignant autobiography, My Beloved World (2013), clearly stated that she was a beneficiary of affirmative action in higher education, agree to sign on with the conservative majority opinion? Joan Biskupic (Reference Biskupic2014), a legal scholar and journalist and who has covered the Supreme Court since 1989 in her book Breaking In: The Rise of Sonia Sotomayor and the Politics of Justice, provides behind-the-scenes interviews with Supreme Court Justices on the Fisher case. She discovered that Justice Sotomayor had actually written a passionate dissent in Fisher, which served to dissuade the conservative members of the Court from striking down the university’s affirmative action program altogether. Her dissent was never made public. Biskupic (2014, 200–20) writes about the process:

In the University of Texas case, it initially looked like a 5–3 lineup. The five conservatives, including Justice Kennedy, wanted to rule against the Texas policy and limit the ability of other universities to use the kinds of admissions programs upheld in Grutter v. Bollinger. The three liberals were ready to dissent. Yet that division would not hold . . . The deliberations among the eight . . . took place over a series of draft opinions, transmitted from computer to computer but also delivered in hard copies by messengers from chamber to chamber as was the long-standing practice.

Biskupic found that several Justices were concerned about the public’s reaction if Justice Sotomayor wrote a dissenting opinion. She writes:

As Sotomayor drafted and began sending her opinion to colleagues’ chambers, they witnessed this intensity. To some, it seemed a dissenting opinion that only Sotomayor, with her Puerto Rican Bronx background, could write. They saw it as the rare instance when she was giving voice to her Latina identity in a legal opinion at the Court . . . Certainly the justices were accustomed to individual differences in cases revolving around race and ethnicity, but in this dispute some were anxious about how Sotomayor’s personal defense of affirmative action and indictment of the majority would ultimately play to the public. (Biskupic Reference Biskupic2014, 205–206).

Biskupic (2014, 208) goes on to say, “If the heated opinion that Sotomayor was drafting in the University of Texas case had made it into the public eye, more fervent conflict would have captured America’s attention.”

Another explanation could be that the agreement to mute the Fisher decision was “a tactical concession by both wings of the Court in a volatile term with …victories and defeats for both progressives and conservatives in landmark marriage equality and voting rights cases” [US v. Windsor and Shelby County v. Holder, respectively] (Powell and Menendian Reference Powell and Menendian2014, 907–908).

So, the Fisher case was sent back to the Fifth Circuit for further review. Now, normally or traditionally, once a case has been remanded and the circuit court makes a decision, the case ends there. However, in a highly unusual, unprecedented move, the Supreme Court agreed to take the case on again, after the Fifth Circuit once again upheld the use of race in admissions. The circuit court agreed with its original ruling and stated, with respect to critical mass that “attaining a critical mass of underrepresented minority students… does not transform [the university’s program] into a quota’” (Fisher 2014, 643, quoting Grutter at 335–336). The court reasoned that the concept of critical mass could not be placed in numerical terms. The goal of diversity is not about “quotas or targets;” rather its focus is on individuals. The Fifth Circuit questioned why the High Court continues to misconstrue and twist the meaning of critical mass by analogizing it to “a numerical game and little more than a cover for quotas” (Fisher 2014, 654).

Now, back in the High Court, a 4–3 ruling was surprisingly issued in June of 2016 in Fisher upholding the use of race-based admissions practices. Recall at the time of the ruling, there were only eight Justices sitting on the Court. Justice Scalia passed away in in February of 2016; and Justice Kagan continued to recuse herself. The majority opinion, written by Justice Kennedy now argued that deference should be paid to universities in such matters as “student body diversity, that are central to its identity and educational mission” (Fisher, 2016, online). Moreover, the Fisher Court now seemed to accept the fact that critical mass defies numerical classification. Kennedy wrote for the majority that “A university is in large part defined by those intangible ‘qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness’” (Fisher, 2016, online, quoting Sweatt v. Painter, 1950: 634). The Court went even further to stress this point. Despite the fact that Kennedy continued to rail against the concept of critical mass in his 2013 opinion in Fisher, he writes in his 2016 majority opinion, that:

As this Court’s cases have made clear . . . the compelling interest that justifies consideration of race in college admissions is not an interest in enrolling a certain number of minority students. Rather, a university may institute a race-conscious admissions program as a means of obtaining ‘the educational benefits that flow from student body diversity’ . . . As this Court has said, enrolling a diverse student body ‘promotes cross-racial understanding, helps to break down racial stereotypes, and enables students to better understand persons of different races’ . . . Equally important, ‘student body diversity promotes learning outcomes, and better prepares students for an increasingly diverse workforce and society’ (Fisher, 2016, online, quoting Fisher 2013 and Grutter 2003).

The Court then went on to conclude that the University of Texas at Austin “cannot be faulted for failing to specify the particular level of minority enrollment at which it believes the educational benefits of diversity will be obtained” (Fisher, 2016, online).

This is certainly a landmark case and indicative of progress, but if Blum is successful in pushing the Harvard case to the High Court, we may be in for another battle, especially since Justice Kennedy has stepped down from the Court.Footnote 13 I would like to turn more broadly to the question of whether progress has been made in terms of social equity, in particular race and gender relations.

HAVE WE MADE PROGRESS IN ACHIEVING SOCIAL EQUITY?

I ask this question to my students every semester, and generally get a mixed response, with some saying absolutely, and others saying that it is equivocal. This latter response captures the sentiment of Mary Guy’s 1993 article in Public Administration Review: “Three Steps Forward, Two Steps Backward.” We have made some progress, but the Black Lives Matter, Time’s Up and #MeToo movements as well as “taking a knee,” the continued use of arbitration clauses and the push for inclusion riders tell us we have a long way to go. Even Sheryl Sandberg (Reference Sandberg2013), the Chief Operating Officer of Facebook, who has continually instructed women to “lean in,” recently stated that women who plan on becoming pregnant should not lean in. Let me first turn to employment progress.

Employment Progress

In terms of public sector employment, which I study in terms of race, gender, and ethnicity, we have seen a good deal of progress in terms of entry into government jobs at every level—local, state, and federal. But progress in terms of gaining entry into the higher, policy-making ranks of government has been relatively slow as many have pointed out (see Gooden and Portillo Reference Gooden and Portillo2011; Gooden Reference Gooden2014; Riccucci Reference Riccucci2009; see Appendix A).

Another area that deserves attention in terms of employment is family responsibilities discrimination (FRD); family responsibilities include caring for a spouse, child, or aging parent, being pregnant, or even the possibility of becoming pregnant and caring for a disabled sibling or child. In short, FRD is the legal concept that describes discrimination against an employee on the basis of her or his responsibilities as a caregiver (Mullins Reference Mullins2016). This concept has been called the newest form of workplace discrimination and particularly the new sex discrimination because it disproportionately affects women. That is, while the literature shows that FRD extends beyond women to all caregivers, FRD legal claims are most often filed by working mothers. Litigation of FRD is on the rise in the public and private sectors in the US. From 1999–2008, FRD claims increased by over 400% in comparison to the previous decade, with verdicts and settlements averaging over $500,000; 88%of the plaintiffs in these cases are women (Calvert, Reference Calvert2010).

While there is no federal law that expressly prohibits discrimination based on family responsibilities, claims can be brought under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act as amended—which includes the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978—the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993, the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, or state or local laws.Footnote 14 Insofar as discrimination occurs as a result of caring for disabled children or relatives, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 also protects workers from FRD (Williams and Bornstein, Reference Williams and Bornstein.2006; Reference Williams and Bornstein.2008; Williams and Segal, Reference Williams and Segal.2003).

Our conception of social equity in political science and public administration has broadened in the last decade or so to include LGBTQ employment. Such scholars as Greg Lewis (2011; 2008), Rod Colvin (Reference Colvin2012) and Donald Haider-Markel (2017; 2014) have made significant inroads in their research on the employment and voting patterns of LGBT persons as well as the implementation of public policies addressing LGBT individuals. In 2015, the High Court in its 5–4 Obergefell v. Hodges ruling upheld the constitutionality of same-sex marriages. Same-sex couples can now marry in all 50 states. Yet, LGBT persons still do not have federal employment protection in all 50 states. Efforts date back to 1994 when the first version of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) was introduced in Congress. But, it failed to gain enough support for passage into law. It has been introduced in virtually every Congress since 1994,Footnote 15 but has failed to muster enough support.

The issue of pay equity or equality continues to be a topic of great interest in this nation, and despite legislation and lawsuits, pay inequity based on gender persists. Data from the US Census Bureau show that women earn 80% of what their male counterparts earn (US Census Bureau 2016). In 1990, the pay gap stood at 70% (US Council of Economic Advisers 1998). While the gap has obviously lessened, it took close to 30 years for it to shrink by only 10%. In the public sector, the picture is a bit different. At the federal level, the US Office of Personnel Management reported that the average female salary is 87.3% of the average male salary (US OPM 2014). There is also a gender pay gap for state and local government workers, but it varies depending upon the location. There are wide variations by state, but nonetheless, the gender pay gap persists even here. In addition, the gender wage gap is even larger for African American and Hispanic women: African American women earn about 69%, and Hispanic women earn not even 60% of median annual earnings for white men (Institute for Women’s Policy Research 2016). If the BBC can boost the salaries of its women journalists, why can’t US companies?

It is also important to point out that we are beginning to see an increasing amount of research with a focus intersectionality, which addresses the unique experiences of individuals who occupy multiple marginalized social categories (see for example, Breslin, Pandey, and Riccucci Reference Breslin, Pandey and Riccucci2017). It refers to the ways in which the various forms of oppression (e.g., racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, classism, etc.) are interconnected and cannot be examined separately from one another.

Representative Bureaucracy

The research on representative bureaucracy also indicates progress in social equity, in that it points to the benefits of diverse workforces. And, importantly, as a number of studies have shown, representative bureaucracies promote democracy and increase government accountability (see, e.g., Meier and Stewart Reference Meier and Stewart1992; Theobald and Haider-Markel Reference Theobald and Haider-Markel2009). It was Kingsley (Reference Kingsley1944) who first theorized that the social composition of bureaucracies should reflect the people they serve as a function of democratic rule; it was a normative theory. Levitan (Reference Levitan1946) was the first to propose that representative bureaucracy theory be applied to the American civil service (also see Long Reference Long1952; Van Riper Reference Van Riper1958). Mosher (Reference Mosher1968) went even further to argue that bureaucrats should push for the needs and interests of their social counterparts in the general population; this manifesto squarely falls within the tradition of the New Public Administration. A number of empirical studies have tested the theory of representative bureaucracy in its various forms, including passive, active, and symbolic. Passive representation refers to the degree to which the demographics of public organizations reflect the demographics of the general population (Meier Reference Meier1993a; Meier Reference Meier1993b; Selden 1997; Kellough 1990). Studies on passive representation have consistently found that, although women and people of color may be well represented in bureaucracies in the aggregate at various levels, they are generally underrepresented in the higher, policy-making positions (Smith and Monaghan 2013; Aikaterini, Sabharwal, Connelly, and Cayer 2016).

Ken Meier, an avatar of representative bureaucracy, greatly advanced the theory of representative bureaucracy. He was one of the first scholars to empirically examine the link between passive and active representation, finding that minority bureaucrats will pursue policies or actions that benefit minorities in the citizenry (see, Meier and Stewart Reference Meier and Stewart1992; Meier, Wrinkle, and Polinard Reference Meier, Wrinkle and Polinard1999). And important work by Sally Selden along with Jess Sowa among others followed (Selden Reference Selden1997a; Reference Selden1997b; Sowa and Selden 2003). For example, a study by Keiser, Wilkins, Meier, and Holland (Reference Keiser, Wilkins, Meier and Holland2002) was the first to find a linkage between passive and active representation for women. Their study found that women math teachers improved the math scores of not only girls, but of boys as well, although the impact was not as large for boys’ scores.

A third strand of representative bureaucracy examines the symbolic effects of passive representation in that the social origins of bureaucrats can induce certain attitudes or behaviors on the part of citizens or clients without the bureaucrat taking any action (Theobald and Haider-Markel Reference Theobald and Haider-Markel2009; Riccucci, Van Ryzin, and Lavena Reference Riccucci, Van Ryzin and Lavena2014). Research by Gade and Wilkins (Reference Gade and Wilkins2013), for example, found that veterans who know or believe that their counselors in the Department of Veterans Affairs are veterans report greater satisfaction with services. As they point out, “passive representation can . . . translate into symbolic representation, where representation may change the attitudes and behaviors of the represented client without any action taken by the bureaucrat” (Gade and Wilkins Reference Gade and Wilkins2013, 267). Theobald and Haider-Markel’s (2009) study found that a predominately African American police force can create greater legitimacy among African Americans in the community, notwithstanding the actions or behaviors of the police officers. They also found that whites are more likely to perceive police actions as legitimate if the actions were taken by white officers.

A number political science and public administration scholars have greatly advanced the representative bureaucracy literature in a host of policy domains; they include Lael Keiser, Sally Selden, Vicky Wilkins, Jill and Sean Nicholson-Crotty, Brian Williams, Jess Sowa, Donald Haider-Markel, Rhys Andrews, Karen Johnston, Amy Smith, K. Jurée Capers, Andrea Headley, and Meghna Sabharwal. In particular, Jill and Sean Nicholson-Crotty along with Jason Grissom and Sergio Fernandez have examined such critical issues as distributional equity, gifted educational services, and most recently, the importance of race representation in police departments, given the violence we are seeing against blacks in our society.Footnote 16

In the US in the past several years, police violence against blacks has once again escalated, resulting in the deaths of a number of young black men, including Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and Terence Crutcher. The shooting death of Michael Brown, for example, a young 18-year-old black man by a City of Ferguson police officer in August of 2014, sparked civil unrest in that city’s black community and strong protests across the country around the brutality of police against black citizens.Footnote 17 These events signaled renewed national interest in the violence against blacks in our society by law enforcement officers, and led to nationwide demonstrations. The Black Lives Matter movement has focused almost exclusively on police brutality against blacks. In response to the unrest, President Obama created a task force to recommend reforms to the problem of police violence (President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing 2015). In addition, the high-profile cases of fatal police shootings prompted a number of reports by the US Justice Department under the direction of former Attorney Generals Eric Holder and Loretta Lynch on police violence against blacks in cities across the country.

The Justice Department has been empowered to investigate systematic constitutional violations in local police departments since 1994, when Section 14141 was included in a crime bill signed by President Clinton. The attorney general was authorized to sue or enter into consent decrees to address the biases. Local governments tend to enter into consent decrees to avoid federal lawsuits. There has been a surge of consent decrees recently with the spike of police violence against blacks. However, since Mr. Trump took office in 2017, the Justice Department under his Attorney General, Jeff Sessions, has been unwilling to interfere with local police matters. In his confirmation hearing, Sessions stated “These lawsuits undermine the respect for police officers” (Stolberg Reference Stolberg2017).

A number of studies consistently show patterns of racial profiling, in that blacks and Latinx are more likely to be targeted by police than whites (Harris Reference Harris2002; Gelman, Andrew, Fagan, and Kiss Reference Gelman, Fagan and Kiss2007; Brunson Reference Brunson2007). For example, in their study of police stops in their phenomenal book Pulled Over: How Police Stops Define Race and Citizenship, Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel (2014, 3) point out that

. . . it is well established that racial minorities are more likely than whites to be stopped by the police. But, disparities in who is stopped are only the most obvious indicator of how police stops both reflect and define racial division in the United States. In stops, racial minorities are questioned, handcuffed, and searched at dramatically higher rates than whites are; they are much more likely than whites to perceive the stop as unfair; and they distrust the police in general at much higher rates than do whites.

In a more recent study, Epp, Maynard-Moody, and Haider-Markel (Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2017), find racial profiling by police in investigatory vehicle stops, where officers disproportionately stop blacks who are driving or walking to question and search them. Not only are they innocent, but the experience of such investigatory stops erodes their trust in police and it also leads to psychological harm. Their research found that blacks’ “common experience of investigatory stops contributes to their perception that they are not regarded by the police as full and equal members of society . . . Investigatory stops . . . are significantly more likely to foster the perception that the police are “out to get people like me” (Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2017, 174). They also point out that many of the high-profile shootings of blacks in recent years occurred during these stops.

Such stops include what are known as “stop-and-frisk” practices. Here police detain and question pedestrians and search them if they believe a crime is being or about to be committed. Often, these encounters can escalate into aggressive actions by police officers, including deadly violence by police. As noted earlier, police often become violent particularly when citizens are engaging in constitutionally-protected free speech, as the US Justice Department has found in their reports examining police violence against blacks. The stop-and-frisk practices of New York City gained national attention because of their pervasive use and propensity to target blacks and Latinx. Eric Garner was a victim of such practices because he was suspected of selling “loosies” (i.e., individual cigarettes) on a New York city street corner. When he stated that he was tired of being harassed by the police, officers attempted to restrain him by putting him in an illegal choke hold. Despite pleas from Garner that “I can’t breathe,” additional officers moved in to restrain him. He died in part as a result of the chokehold.

An article in the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory (JPART) examines experimentally the symbolic representation effects of race in policing (Riccucci, Van Ryzin, and Jackson Reference Riccucci, Van Ryzin and Jackson2018). The study varies the representation of black officers in a hypothetical police department and also varies the agency’s complaints of police misconduct, including stop-and-frisk practices to determine how citizens view the police. It finds support for the existence of a symbolic representation effect: the racial composition of the police force does seem to causally influence how citizens view and judge a law enforcement agency. Specifically, the study found that blacks respond more favorably toward the police when there are more black officers on the force, regardless of whether complaints increase or decrease. This would suggest that, given a predominately black police force, black citizens may be more tolerant of aggressive police practices such as stop-and-frisk.Footnote 18 Thus, although the presence of black police officers may lead to an increase in racial profiling, as Wilkins and Williams (Reference Wilkins and Williams2008) found in their study, the results of this forthcoming study suggest that this may be offset to some extent by enhanced trust and legitimacy on the part of black citizens.

If police departments across the country are genuinely interested in improving police-community relations and in restoring trust of the police among black citizens, diversifying police forces so that they are more representative of the communities they serve will produce more trust and legitimacy in the eyes of citizens. Nicholson-Crotty, Nicholson-Crotty, and Fernandez (2017, 206) in their exceptional study found that “More black officers are obviously seen, in part, as a way to directly reduce unnecessary violence between police and citizens.” They go on to say that “Increased diversity or representation of minorities is also proposed as a way to indirectly reduce violence by enhancing the legitimacy of the police force within communities.” Certainly, we will see additional research on this important topic in the future.

Social Equity in Academe

The faculty profile at institutions of higher education in the US continues to be mostly white and largely men (Warikoo Reference Warikoo2016; McMurtrie Reference McMurtrie2016; Brown Reference Brown2004). This somewhat holds true for such fields such as public administration and political science depending upon faculty rank. In public administration, for example, we have made progress in terms of increases of white women in the field, but the higher ranks continue to be dominated by white men. Leisha DeHart-Davis (2017), who with Mary Feeney spearheaded the creation of Academic Women in Public Administration (AWPA), invited comments through an anonymous Qualtrics survey posted on Twitter, the AWPA email list, and the Public Management Research Association’s (PMRA’s) listserv on the following questions: “Based on your experiences, is public administration a diverse and inclusive academic field? Why or why not? If not, what can be done? All thoughts, ideas, comments, suggestions, critiques welcome.” While only 25people posted comments, the responses were varied and provocative, and were summarized by Professor DeHart-Davis. Responses included:

• Public administration is (not) a diverse academic field;

• International students, particularly those from China and Korea, bring diversity to PA;

• While Asian students do indeed bring diversity, it cannot be used as an excuse for ignoring the call for US public administration to be more inclusive of women and faculty of color;

• Public administration is a white field that excludes minority voices;

• White men are overrepresented in power positions;

• The creation of Academic Women in Public Administration was viewed by some as positive, but others suspect self-serving motives and white feminism at play.

Other public administration faculty members across the US were invited to comment on this issue (DeHart-Davis 2017, 3–7). They echoed some of the comments made by the anonymous respondents to the Qualtrics survey. This is certainly an issue that deserves greater attention and asks the question, have the aims and objectives of New Public Administration been realized? But we also need to ask: how does the field define diversity? What exactly does it mean? And what is the unit of analysis? Are we looking at students, faculty, deans, chairs, directors, and/or journal editors-in-chief? Parenthetically, the Minnowbrook I conference had no persons of color nor women present.

DeHart Davis’ survey was a response to a 2016 Washington Post op-ed piece written by Professor Marybeth Gasman of the University of Pennsylvania (Gasman Reference Gasman2016). Gasman wrote that there is little diversity among faculties at elite universities because they do not want faculty of color. She argued that universities exclude them because they may not have graduate degrees from elite universities, there is a perception of low-quality scholarship and there is an absence of people of color in the faculty pipeline. All of these pretexts, of course, can be explained away, and this is why Gasman concludes that university faculties simply do not value diversity. Can this be the case for us in public administration and political science?Footnote 19

CONCLUSION

In closing, let me return to the writing of John Gaus (1947, 124), whose words are particularly relevant and prevailing today: “The inclusion of greater numbers of persons in political activity and the increased dependence of populations on the results of this activity make our individual and group ideas of ends and means of public housekeeping more important. Such ideas influence our decisions and acts . . . The decisions and acts have long led to policies that affect our standard of living and for many, life itself . . . New forms of war, embodying doctrines of race or class . . . have increased the urgency and importance of decisions and policies.”

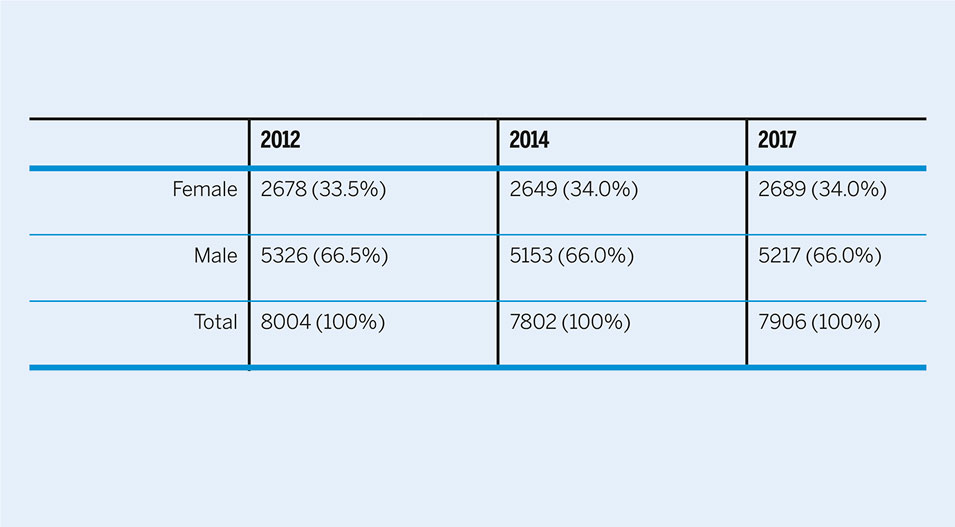

Appendix A; Table 1 Senior Executive Service (SES) Gender Trends

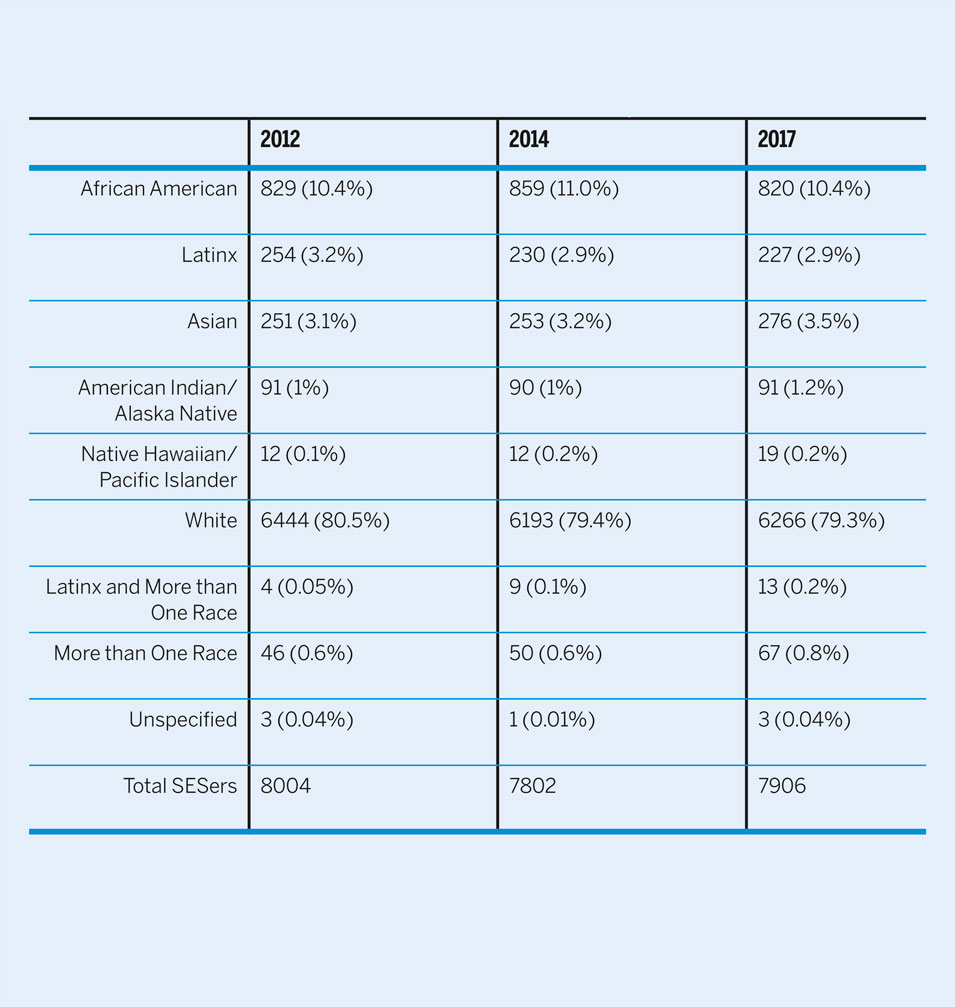

Appendix A; Table 2 Senior Executive Service (SES) Ethnicity and Race Trends