Introduction

All governance systems require policing to monitor and enforce social rules, but without effective constraints, police will engage in socially destructive activities (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan1975). Thus, how does a policing system remain reliable – defined by the enforcement of rules and property rights – without devolving into predation? Despite the potential for abuse, many communities have effectively devised self-governing policing institutions, even when formal states are non-existent or far removed (Anderson and Hill, Reference Anderson and Hill2004; Ellickson, Reference Ellickson1991; Leeson, Reference Leeson2014a; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990; Skarbek, Reference Skarbek2011, Reference Skarbek2012).

This paper examines how the pre-colonial Mandan and Hidatsa tribes – two closely related groups of Great Plains Native Americans – effectively constrained their quasi-police force, known as the Black Mouth Society. Although historians, sociologists, and anthropologists have written about the Black Mouths (see Bowers, Reference Bowers1950, Reference Bowers1963; Densmore, Reference Densmore1923; Fenn, Reference Fenn2014; Lowie, Reference Lowie1913; MacLeod, Reference Macleod1937), economists have said little about the Mandan–Hidatsa policing system. These tribes provide a compelling example of how self-governing groups can overcome challenges posed by police powers. When police are reliably empowered and constrained, self-governing societies can engage in socially productive activities while limiting destructive ones.

The theoretical and empirical scholarship offers four general principles by which policing systems demonstrate reliability. First, a community requires rules that are known to the community members and perceived as legitimate. Second, a system of monitoring must dissuade people from violating those rules and determine violations. Third, mechanisms of enforcement and dispute resolution must mitigate social conflict and punish rule violators in proportion to the violation. Fourth, mechanisms of accountability must constrain monitors and enforcers to avoid abuses of power and punish abuses when they occur. Without accountability for police, abuses of power are likely to arise, leading to expropriation, arbitrary favouritism, and violence.

The pre-colonial Mandan and Hidatsa tribes shared a complex governance structure that displayed these four principles. Their communities consisted of several semi-sedentary villages, each with its own independent governing institutions of a council and several chiefs, who made collective decisions in power-sharing arrangements. Nearly all people in these tribes belonged to age-grade fraternal and sororal organizations called ‘societies’, which divided responsibilities to facilitate social order.

The Black Mouth Society was the fraternal organization to which the council and chiefs granted the power to monitor and enforce rules and collective decisions, making them a de facto police force. As a symbol of their station, Black Mouths painted the upper half of their faces red and the lower half of their faces black (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 109). The Black Mouths had a relatively large amount of power to keep order within each village, ensure safety on the summer hunt, protect the village from external threats, and serve as arbiters among different villages or tribes. The Black Mouths were these tribes' main source of policing until the US federal government forced the tribes onto a reservation in the late 19th century.

The Mandan–Hidatsa policing system was reliable because mechanisms on the front and back ends mitigated and punished abuses of power. On the front end, the governance system mandated a long probationary period and unanimous consent for a man to become a Black Mouth, mitigating the chances for predation. Prospective Black Mouths had to successfully advance through lower fraternal groups and be middle-aged to demonstrate good character. The incumbent Black Mouths and the more elderly men's groups had a unanimous (or near unanimous) decision rule for admitting new Black Mouths, which reduced the likelihood of bad actors gaining power. Black Mouths faced strong incentives not to shirk or abuse responsibilities. A position in the Black Mouths was a high social honour, and shirking responsibilities would have harmed one's reputation, thus undermining future advancement in the age-grade fraternal societies or becoming chiefs/council members.

However, occasionally, individual Black Mouths abused their power. Therefore, on the back end, a system of social sanctions rectified abuses through public shame and restitution. Public communication created common knowledge, leading to public ridicule that undermined an abusive Black Mouth's legitimacy, limiting his ability to further abuse power. Moreover, Black Mouths were socially obligated to compensate individuals who they unjustly punished.

Our analysis contributes to two strands of literature. First is the scholarship on self-governance and policing, especially when states are non-existent or weak (Leeson, Reference Leeson2007a, Reference Leeson2007b, Reference Leeson2008, Reference Leeson2009a, Reference Leeson2014a, Reference Leeson2014b; Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili, Reference Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili2021; Stringham, Reference Stringham2015; Thompson, Reference Thompsonforthcoming). Second is the scholarship on the complex nature of Native American governance and policing (Alston et al., Reference Alston, Crepelle, Law and Murtazashvili2021; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Benson and Flanagan2006; Crepelle et al., Reference Crepelle, Fegley and Murtazashvili2022, Reference Crepelle, Fegley, Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili2024; Piano and Rouanet, Reference Piano and Rouanet2022).

We proceed as follows. The second section outlines the conditions for effective governance systems and reliable policing. The third section describes the social and political structures of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes, including the village councils, chiefs, and the Black Mouth Society. The fourth section describes how the Mandan and Hidatsa's institutions sufficiently constrained the power of the Black Mouth Society to facilitate reliable policing over long periods. The final section concludes.

Principles of effective governance and reliable policing

All societies need governance systems to promote positive-sum, socially beneficial actions and mitigate negative-sum, socially harmful ones (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan1975). If states are non-existent, weak, ineffective, or corrupt, communities can develop norms and rules that provide social order absent top-down, bureaucratic oversight (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Arnold and Villamayor Tomás2010; Dixit, Reference Dixit2004; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990). Even without strong, centralized states, individuals across the world have secured their property rights and facilitated social cooperation by setting up institutions of self-governance (Leeson, Reference Leeson2007a, Reference Leeson2007b, Reference Leeson2008, Reference Leeson2009a, Reference Leeson2014a, Reference Leeson2014b). Social order, including policing and security services, can arise when institutions have characteristics that align personal incentives with the broader social benefit. Even under statelessness, social groups who are avowed enemies have created institutions that facilitate peace and cooperation (Leeson, Reference Leeson2009b).

Other historical and contemporary examples demonstrate effective self-governance. During the settlement of the western United States, governance institutions and policing functioned relatively well without direct government control, as evidenced by the operation of mining camps, wagon trains, and cattle ranches (Anderson and Hill, Reference Anderson and Hill2004; Ellickson, Reference Ellickson1991). North American indigenous peoples have a long history of governance institutions that protected property rights and promoted social cooperation (Johnsen, Reference Johnsen2024). Additionally, local-level institutions of self-governance in Afghanistan have managed complex matters of land and resources, while protecting citizens from government predation (Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili, Reference Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili2015, Reference Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili2016, Reference Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili2021).

Taken together, this literature identifies four institutional features of effective systems of self-governance and reliable policing. First, a community must develop rules that are known to all community members and perceived as legitimate. These self-governing rules – whether endogenously emergent or consciously designed – must incentivize socially beneficial action (e.g. production and exchange) while disincentivizing socially harmful action (e.g. predation and violence). Second, institutional mechanisms must exist to monitor whether people are following social rules. In many situations, individuals may be tempted to violate social rules for personal gain, despite broader social harm. Thus, monitors provide a disincentive for people to break the rules and can ascertain whether someone has broken a rule. Third, institutional mechanisms must exist to enforce rules and punish violations. Without enforcement and punishment, predation and violence may become widespread, making it difficult to form long-term expectations and invest in productive activities. Fourth, mechanisms of accountability must exist for the monitors and enforcers of social rules (i.e. police), who might abuse their power. Without a system of accountability and rectification, societies will likely devolve into the arbitrary predation by the stronger against the weaker.

Thus, our core argument focuses mainly on this last point. For a policing system to maintain social order reliably and successfully, governance institutions must hold the police accountable for their actions. A system of self-governance is only as dependable as the reliability of its policing system.

Governance systems of the Mandan and Hidatsa

Mandan and Hidatsa social organization

The Mandan and Hidatsa tribes live on the northern Great Plains of the United States. Their homelands overlap geographically, and they share many institutional, linguistic, and cultural features. Today, these two tribes, along with the Arikara, are federally recognized as the Three Affiliated Tribes. Since 1870, the three tribes have shared North Dakota's Fort Berthold Indian Reservation.

These three tribes originated in different areas and coalesced into a relatively similar culture around 1800 C.E. The Mandan were the first group to migrate into what is now their homeland in North Dakota, from southern Minnesota and South Dakota, around 1150–1400 C.E. The Hidatsa arrived about 1400–1650 C.E. from the eastern part of North Dakota near Devils Lake.

The Mandan and Hidatsa spoke related languages in the Siouan language family and have coexisted in the same region for at least 350 years, allowing them to develop significant cultural and institutional overlap. The Arikara joined with the Mandan–Hidatsa villages slightly before or around 1800 after migrating from the southern Great Plains. Unlike the Mandan and Hidatsa, the Arikara language is from the Caddoan language family, but the Arikara adopted many Mandan–Hidatsa institutions (Densmore, Reference Densmore1923; Wolf Tice, Reference Wolf Tice2016: 1–19). Our discussion here focuses only on the Mandan and Hidatsa, but it applies to the Arikara as far as they adopted the same institutions.

Historically, the Mandan and Hidatsa lived in semi-permanent villages built near the upper Missouri River and its tributaries. These villages functioned independently, even though they shared similar social and governance structures (Bowers, Reference Bowers1950: 36; Reference Bowers1963: 14). Villages were composed of several matrilineal clans. Extended families often lived together in large ‘earth lodges’, which were circular, semi-subterranean houses covered by grass and soil (Linton, Reference Linton1924). Villages were protected by a wall of wood or a ditch to defend against enemy raids (Bowers, Reference Bowers1950: 23–24). In and around the villages, women engaged in small-scale agriculture, growing corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers. Men hunted and fished to provide food, clothing, etc. (Bowers, Reference Bowers1950: 23; Densmore, Reference Densmore1923: 5). In the 18th and the early 19th centuries, the number of villages was between 9 and 13, each containing anywhere from 12 to over 100 earth lodges (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963). Before major disease-caused population declines in the 1830s, the Mandan–Hidatsa population was 12,000–15,000 people (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014).

The social practices and living situations changed with the seasons. During summer, women tended the gardens near the villages (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 39). Another important summer activity was the month-long bison hunt, involving many of the younger men and women, while older women, children, and elderly men were left behind in the village. Some able-bodied adult men remained in the village to protect against raiding parties (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 50). In the autumn and winter, after the crops had been harvested and stored, people moved into smaller lodges in the river bottoms of the Missouri River or its tributaries. River bottoms provided additional shelter against the elements, and bison would often gather there (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 56–63).

The Mandan and Hidatsa communities had a unique social structure in which nearly all adolescents and adults belonged to age-grade ‘societies’, i.e. fraternities or sororities. Each of these groups had specific social functions for the villages (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 175; Fowler, Reference Fowler2003: 67–69). Generally, individuals younger than 12 years old were not members of age-grade societies, and elderly individuals who had passed through the entire age-grade system were no longer part of one of these groups.

Relative age determined one's age-grade society, each of which was formally organized with official names, symbols of membership, songs, and prescribed rights and rules of behaviour (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 174). Individuals would progress through the age-grade societies in a prescribed sequential order, and an individual could not skip any intermediate societies. Membership in a society was not guaranteed, and individuals lost their society membership due to poor performance (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 193). Age-grade societies were common among several Great Plains tribes, including the Arapaho, Gros Ventre, Blackfoot, Mandan, and Hidatsa, but the Mandan and Hidatsa had the most similar and closely related systems (Lowie, Reference Lowie and Wissler1916; Whyte, Reference Whyte1944). Age-grade societies are a common institution across the globe, including in traditional African governance (Fosbrooke, Reference Fosbrooke1956).

Membership in an age-grade society was tied to important religious rituals and practical social responsibilities. For example, women's were associated with the traditionally feminine role of agricultural production (Wolf Tice, Reference Wolf Tice2016: 32–34). When there was a shortage of meat, the elderly women of the Buffalo Cow Society engaged in spiritual rituals to draw bison near to the village. The middle-aged women of the Goose Woman Society performed rituals to summon good weather for the spring planting season (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 107–109). Men progressed through several societies, including the Notched Stick, Stone Hammer, Fox, Lumpwood, Half-Shaved Heads, Black Mouth, Young Dog, Crazy/Foolish Dog, Old Dog, Buffalo, Bad Ear, Horse, and Coarse Hair societies. Most of these societies were common to both the Mandan and Hidatsa, but some were unique to only one tribe (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 175; Densmore, Reference Densmore1923: 94–144).

Individuals benefited from joining a fraternal or sororal society for at least two reasons: social prestige and engagement in religious rites. Each age-grade society combined religious and practical functions, with internal officers for each group's governance (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 63). The ability to engage in sacred rites was bought, sold, and transferred among individuals, and some rites were strictly tied to membership in a society. Sacred rites could only be performed with a collection of artefacts, called ‘bundles’, which required learning about associated rites, privileges, songs, stories, obligations, and traditions (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 105). Good performance in an age-grade society demonstrated trustworthiness and responsibility, granting individuals social prestige and approbation (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 108).

A growing literature emphasizes the importance of supernatural power and religious beliefs to social governance from a rational-choice perspective (see Leeson, Reference Leeson2012, Reference Leeson2014b, Reference Leeson2014c, Reference Leeson2014d, Reference Leeson2021). Although longstanding superstitious beliefs are seemingly irrational, they produce rational outcomes by enhancing social trust, enforcing cooperation, mitigating conflicts, and punishing anti-social behaviour. Concepts of supernatural power affected and shaped Mandan–Hidatsa governance, and the age-grade societies were intimately connected to religious beliefs and rituals. In the Mandan–Hidatsa belief structure, villagers needed to acquire supernatural power for their protection and flourishing, which came through fasting, ritual performances, feasts, and other ceremonies. Death was ascribed to a loss or neglect of supernatural power, caused by a variety of spiritual offenses, such as violating tribal rules and mistreating other tribal members, as well as improper fasting or mistakenly interpreting premonitions, etc. (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 282–283).

One's social status was not necessarily measured by the accumulation of personal property. The most highly regarded people were usually not the wealthiest because one important measure of status was the amount of goods that were given away publicly and privately, especially during religious ceremonies (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 289). This is not to say that individuals were pleased to become net financial losers or cared little for their financial wellbeing. Instead, an economic perspective assumes that individuals make rational calculations, balancing the short-term costs and long-term expected benefits.

In the early- to mid-18th century, the Mandan and Hidatsa were introduced to the horse and European firearms, as were their enemies. The tribes first acquired horses between 1730 and 1750. The Mandan and Hidatsa never became fully nomadic equestrians like the Comanche or Lakota tribes, but they incorporated horses into many aspects of their lives (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 132–142). Horses did not fundamentally change the tribes' governance structure or agrarian lifestyle, but more distant hunting parties became viable. Since enemy tribes also had horses, individuals left behind in the villages during a hunt were more vulnerable to enemy attack (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 142–145).

The Mandan acquired their earliest guns in the early 18th century from the Hudson's Bay Company, French fur traders, and other tribes. Guns, unlike horses, did not change buffalo hunting because the muskets were hard to load, aim, and fire while on horseback. The Mandan and Hidatsa continued to use lances or bows and arrows to hunt. When enemy raiders attacked villages, guns provided an advantage in self-defence. Defenders would shoot from behind village walls, usually scaring away the attackers (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 146–148).

Systems of collective decision-making and policing

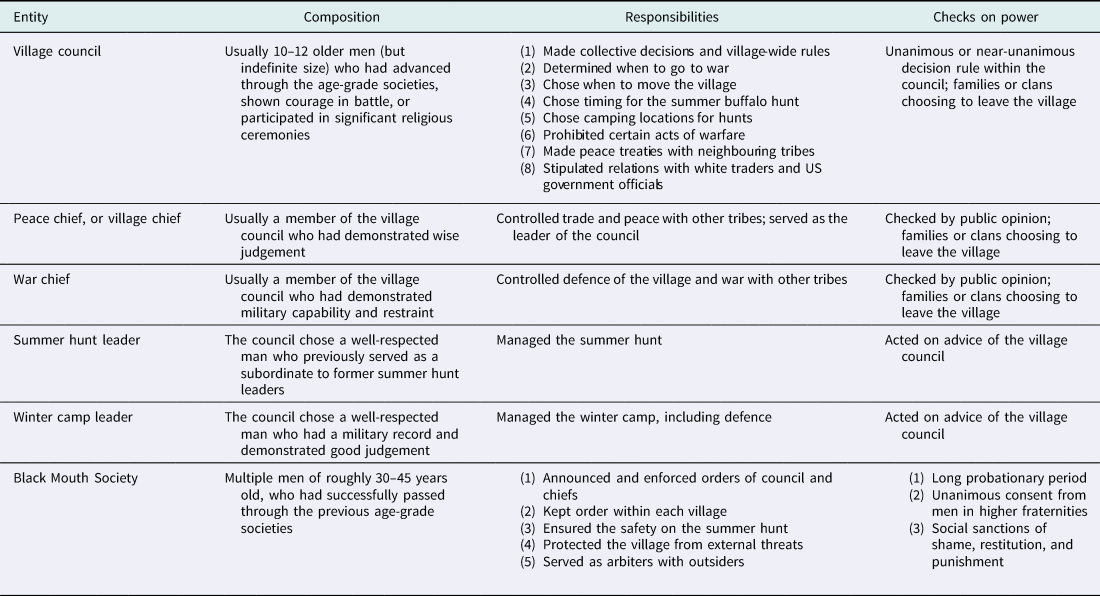

A village's collective decisions were made by council composed of approximately 10–12 elderly men and four chiefs who had distinct responsibilities. The Black Mouth Society, also known as the Brave Men's Society or the Soldiers, served as the monitors and enforcers of the council's and chiefs' decisions (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 27–64). Table 1 provides an overview of the key governance entities, their social functions, and how their power was checked.

Table 1. Governance structure of Mandan and Hidatsa villages

Source: This table was created by authors with information from Birdsbill Ford (Reference Birdsbill Ford2001); Bowers (Reference Bowers1950, Reference Bowers1963); and Lowie (Reference Lowie1913).

The council made decisions for community-wide issues of warfare and mutual assistance, such as moving the village, choosing the timing for the summer buffalo hunt, choosing camping locations for hunts, prohibiting certain acts of warfare, making peace treaties with neighbouring tribes, and stipulating relations with white traders and US government officials (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 27–28, 33). The councils tried to arrive at unanimous decisions, but when they did not, the members in the majority would attempt to persuade the minority. If unanimous decisions could not be reached, the decisions were often postponed (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 29). Prestige on the council was gained over time through persuasion, deliberation, and evidence of good judgement. Since villages were relatively small, near-unanimous decisions ensured effective collective decisions through legitimacy and reduced external costs. Council members frequently gave all households an opportunity to express an opinion (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 33).

The council's collective decisions had to please nearly all the households in the village because of the possibility of exit. When an extended family was dissatisfied with village leadership, rather than engaging in conflict, they could establish a new village or join another (Bowers, Reference Bowers1950: 28; Reference Bowers1963: 34). In some cases, families would return if they respected the new leadership (Birdsbill Ford, Reference Birdsbill Ford2001; Bowers, Reference Bowers1963).

Of course, moving to a different village was not costless or riskless, especially due to diseases and military threats. The secondary historical literature indicates that people occasionally moved to different villages or started new ones, which indicates that exit costs were not prohibitively high. A situation in which exit is an option, although costly to some degree, disciplines collective-decision-makers to make more prudent and socially beneficial decisions relative to what they would otherwise make if exit were not an option at all.

Within each village, there were at least four types of chiefs: peace chief, war chief, summer camp chief, and winter camp chief. Chiefs were generally selected by the village council, and many of the chiefs were members of the council (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 26). Chiefs were expected to conform strictly to established rules and customs and had their power checked by the village council and public opinion (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 56).

The peace chief, also known as the village chief, oversaw important ceremonies, controlled trade, and facilitated peaceful relations with other tribes (Bowers, Reference Bowers1950: 33–35; Reference Bowers1963: 26–27). A peace chief served as the leader of the council, and his authority was based on his ability to persuade the council to sanction his opinions. The members of a village would judge a chief's greatness ‘based on the length of time that his opinions were accepted to the exclusion of all others’ opinions’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1950: 35).

The war chief oversaw military needs and prepared the villages for enemy raids. The council appointed one of its members to be the war chief, who remained in power if he retained the good will and respect of the entire community (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 42). The war chief's responsibilities mainly occurred in the summer months when warfare was actively conducted. During winter, when warfare was usually discontinued, the winter camp chief took precedence (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 42). The war chief attempted to dissipate intra-village conflict or dissatisfaction through several means including, inviting individuals who expressed opposition to him to air their grievances, showing generosity/good will, or suggesting that another person take over his work. When a war chief grew old, he would relinquish his position to a younger man who had passed Black Mouth age (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 42).

In the summer, the council appoints a summer hunt leader, also known as a summer camp chief, who was tasked with ensuring that the hunt was safe and successful. He was in power from the time the group left the earth-lodge village until it returned about a month later (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 56). Councils usually chose summer hunt leaders who had success as a subordinate to former summer hunt leaders and were well-respected by the village. The council considered different men until one could be selected with unanimous consent. The fear of responsibility for prolonged debate over leader selection, which was associated with bad luck, was sufficient to dissipate most opposition (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 51).

The council appointed a winter camp leader, also known as the winter camp chief, who selected the winter campsite, decided when to move the camp, and supervised the group (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 57). He also set the time of the winter ceremonies, regulated camp activities during religious ceremonies, and placed restrictions on movements when enemies or bison herds were near (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 57). The council chose winter camp leader based on their ‘military record, interest in public matters, participation in the village and tribal rites, generosity and kindness to the old, good judgment, and personality’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 58). The winter camp leader only held authority for the period outside of the summer village. A winter camp leader received credit for any enemies killed during the winter, but he was also responsible for any of his own people killed by the enemy. Active warfare was rare in the winter, except when the village was attacked (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 57–58).

If the council could not come to a consensus on who would serve as winter camp leader, then the village had three options. First, no leader would be chosen, and households were free to move in small groups under leaders of their own choosing. Second, the population would remain in the summer village under the existing leadership. Third, the Black Mouth Society would collectively assume the duties and responsibilities of winter camp leader in addition to the role of police. Using the Black Mouth Society as a winter camp leader was a fairly common occurrence because the council wanted to avoid rivalry and hard feelings. In these cases, the Black Mouth Society ‘selected the campsites, set the date for moving from the summer village, supervised the party when moving to camp, and kept in continuous session with a separate council lodge for the meetings during winter’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 187).

Villagers viewed the Black Mouth Society as the legitimate entity for resolving social disputes, enforcing social rules, and guarding the village, making membership in the Black Mouths a sign of respectability. Black Mouths were able-bodied men in their thirties or forties, who were often a village's strongest and most well-trained in warfare. They had the physical strength and skills to coerce rule-breakers, stop conflicts, and engage in defence (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 162, 186–189; Densmore, Reference Densmore1923: 47). Evidence suggests that the Black Mouth Society originated with the Mandan and was later adopted by the Hidatsa, and then the Arikara (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 176; Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 276–280; MacLeod, Reference Macleod1937). Secondary works by historians and anthropologists do not provide a precise answer regarding what fraction of a village's members was a Black Mouth. However, Black Mouths were a relatively small proportion of a village's population since the group included only a subset of the men between the ages of roughly 30–45 (Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 274, 314).

Black Mouths would assemble every 2–3 days to meet with the council, chiefs, and higher-ranked age-grade societies (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 109). After the council and chiefs made collective decisions, an announcer from the Black Mouths informed the villagers of the decision. The Black Mouths daily responsibilities included ‘organizing the group for the performance of winter buffalo-calling rites, the prohibition against premature hunting, firing of guns, and noise around the village, and even the prohibition of kindling fires, when the herds were observed approaching the camp’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 185–187). The Black Mouths always reported to the council and the appropriate chief, which depended on the time of year and the context.

On summer hunts, the Black Mouths monitored and enforced safety protocols, as designated by the summer camp chief. Since enemy tribes would sometimes ambush the summer hunt parties, the Mandan and Hidatsa used a camp circle as a defensive tactic. The Black Mouths oversaw the formation of the camp circle to ensure that all the tipis were properly spaced to complete the circle while also leaving enough room to bring the horses into the circle at night. While the tipis were being set up, the men in age-grade societies beneath the Black Mouths would take the horses to graze, and some of the Black Mouths served as scouts to protect against attacks (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 53).

To hunt the bison effectively, the hunting party required coordination, so everyone needed to follow the summer hunt chief and his designated subordinates' plan. Under the summer hunt leader's direction, the ‘Black Mouths policed the party, driving stragglers back, assisting the laggards or those encountering difficulty of travel, and looking after the general welfare of the group’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 52–53). The Black Mouths ‘enforced regulations against straying away from the main body, prohibited premature attacks on the herds, and defended the group from attack’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 188). Anyone who went hunting alone could scare off the bison or otherwise undermine the plan that the leader had constructed, making the entire group worse off. The Black Mouths punished anyone hunting alone or otherwise subverting the hunting plan (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 53). To ensure the safety of their community members, the Black Mouths prohibited ritualistic fasting outside of the summer hunting camp when enemy raiding parties posed a danger.

The Black Mouths did not directly take part in the buffalo hunt since they were pre-occupied with ensuring that everyone in the hunting party followed the rules and guarding against attack. Thus, others in the hunting party were socially obligated to give part of their meat to the Black Mouths as compensation for their services (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 188). The secondary historical literature seems to indicate that receiving meat during the summer hunt was the only direct compensation for Black Mouths, and there were no other direct forms of funding or remuneration for their services. As discussed previously, other villagers voluntarily shared food with the Black Mouths due to the fear of social sanctions and their religious beliefs.

Black Mouths enforced rules in the winter camps, but there were usually far fewer rules in the winter camps because of fewer enemy attacks and fewer coordinated bison hunts (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 58). At the same time, the Black Mouths were in continuous session during most of the winter because the winter camps were not as well defended as the summer villages. Black Mouths sent out scouts to follow the movements of enemy groups and ensured that the horses were brought in quickly in case of an impending enemy attack (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 186).

The Black Mouths had some discretion in how they enforced social rules, but they had no discretion over the content of the rules. During the winter when the tribes were in the river-bottom camps, it was especially important to prevent premature hunting that could scare off the herds, leaving everyone in the village without a reliable source of food and other useful materials. Buffalo herds were easily startled, and the winter chief knew that the herds must be left undisturbed in the river bottoms for a few days to become settled. The winter camp chief, in consultation with the council, would issue rules regarding when and where hunting would be allowed to maximize the returns to the tribe. When the herds approached the river bottoms in the winter, ‘the Black Mouths were on constant guard to see that no person hunted prematurely; […] the Black Mouths had the authority, fortified by public opinion, to take such measures as they deemed necessary to enforce the “no hunting” orders of the winter chief’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 60). Any punishment they inflicted on violators of the rules was subject to the approbation of the village at large.

When an enemy war party had been reported, the appropriate chief would organize a defensive system, and the Black Mouths would ensure that the chief's orders were followed. Since leadership was heavily reliant on reputation and track record, ‘[e]ach individual killed or wounded represented a mark against the leader's record. Therefore, the good leader was careful to maintain discipline and to prohibit individual and disorganized breaking of camp unless danger of attack was very remote’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 61). Everyone in a village accepted that the Black Mouth would only implement the leader's orders, not make their own rules.

The Black Mouths defended against frequent attacks by enemy tribes, such as the Lakota. The Lakota adopted a nomadic lifestyle upon the introduction of the horse, protecting them against smallpox epidemics that had decimated the sedentary Mandan and Hidatsa. The relative strength of the Lakota led to many raids against Mandan or Hidatsa villages, necessitating more robust monitoring and enforcement of defence-related rules (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 165–171). Thus, warfare and defence-related skills were required for all Mandan and Hidatsa men, but the Black Mouths ensured that glory-seeking younger men did not conduct unauthorized war parties, which could easily jeopardize public welfare or mutual defence (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 219–223).

The Black Mouths only involved themselves with public matters affecting the entire village population. They did not have authority to interfere in personal matters that clans and households could handle themselves, such as intra-clan theft (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 185). ‘Public matters’ consisted of the rules or collective decisions of the council and the chief, as well as anything that could jeopardize the village's safety, such as raids by enemies, or internal peace, such as disagreements between clans.

The Black Mouths were known for quick and severe punishments for violating collective decisions, largely because violating the rules could ultimately lead to war or insufficient food. Black Mouths routinely carried clubs and were authorized to use them against individuals who violated any rules (Birdsbill Ford, Reference Birdsbill Ford2001: 18). If a villager fired a gun or went hunting when the council had forbidden such actions, the Black Mouths took the weapons away from the offender, or they would inflict other forms of punishment, such as cutting up the clothing of the offended, killing the offender's horse, or destroying the illegally obtained meat (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 188–189). In particular, unauthorized war parties or raids could create deadly conflicts between other bands who had formed peace negotiations with the village councils, but young men were often tempted by glory-seeking and social prestige. If young men embarked on unauthorized raids, the Black Mouths would kill the horses brought back from the raid, whip the offending young men, and destroy their weapons. In the most extreme cases, the Black Mouths would burn down the transgressor's house (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 193; Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 277–278).

The Black Mouths helped ameliorate conflicts between members of the various communities and clans, and helped resolve conflicts when a fellow Black Mouth was the source of contention. When a dispute arose between two individuals, a Black Mouth spokesman was chosen from the same clan as each of the disputants. This spokesman would serve as a ‘pipe-bearer’. In Mandan–Hidatsa culture, pipes were involved in a mythologically important smoking ceremony that was a symbolic gesture of reconciliation, and Black Mouths in each village possessed two sacred pipes for such purposes (Fenn, Reference Fenn2014: 36–39; Will and Spinden, Reference Will and Spinden1906: 136). The pipe-bearing Black Mouth for one disputant would take a pipe belonging to his clan and ask the disputant to smoke the pipe as a symbol of overcoming his grievance. The same procedure occurred on the opposing side (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 189–190).

If social strife arose between friendly tribes, the Black Mouths would attempt to facilitate reconciliation (Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 277). The Black Mouths were tied to the village where they lived, and they had no authority over the actions of people in neighbouring villages. The Black Mouths in each village worked to bring about justice and limit inter-village disputes. For example, if a thief in one village stole something from a member of another village, the victim would report the issue to the Black Mouths of his or her village. That group of Black Mouths would then approach the Black Mouths in the village of the accused thief. The Black Mouths in the suspect's own village would search the suspect's lodge or person for the missing property. If the Black Mouths found the property, they would turn over the belongings to the Black Mouths in the victim's village (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 190–191). Secondary works by historians do not indicate any institutional restrictions on such searches.

The Black Mouths also kept the peace when outsiders or enemy groups were near their villages. If a fight broke out between two individuals of opposing groups, a Black Mouth would seize the person from his own village while refraining from directly engaging with members of the other group (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 191). The Black Mouths also mediated between white traders and Mandan–Hidatsa villagers. Traders often recognized the Black Mouths as policeman around the trading post, serving as an intermediary between the traders and Native Americans to preserve peace and order. If village councils gave orders that no hunting or woodcutting was permitted while the bison herds moved into the river bottoms, white traders complied because the Black Mouths would enforce the ‘no hunting’ rules on everyone within their jurisdiction (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 192).

The Black Mouths were responsible for the safety and good conduct of their people whenever visiting tribes were in their village. Since the Mandan and Hidatsa produced agricultural products, other tribes would visit their villages to trade. Sometimes, these visitors were from tribes who had killed Mandan or Hidatsa members, and the family members of the dead had the socially recognized right to refuse admittance of the visitors. The council had two alternative choices: compensate the mourners with horses and other valuables or refuse to admit the enemy band who wanted to trade. In general, the mourners were compensated, unless they had especially strong feelings. The Black Mouths were obligated to give the goods and horses to the mourning family and carry the ceremonial ‘society pipe’ to them as a sign of agreement (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 191).

When violators of social rules demonstrated genuine repentance, the Black Mouths repaid the confiscated or destroyed goods. Depending on the context, the repayment could be larger than the value that was confiscated or destroyed. However, if the offender resisted the Black Mouths or ignored their prohibitions, the offender was beaten (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 188–193; Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 277–278). Additionally, if a villager wanted to kill a fellow village member, the Black Mouths may give gifts to persuade him to reconsider. By accepting the Black Mouths gifts, the angry villager showed publicly that he had reconsidered his anger (Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 314).

The secondary works by historians and anthropologists are not explicit about the specific details of this compensation scheme for penitent violators, but the existing evidence allows for logical inferences. Although these communities lacked a formal system of public finance, there is some evidence of voluntary community contributions from non-Black Mouths. Evidence also suggests that Black Mouths used their own wealth to compensate the penitent or the offended (Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 278). Why would anyone, Black Mouth or not, want to give away their wealth absent compulsion?

Within the system of governance in Mandan and Hidatsa villages, power and prestige – such as advancement to higher age-grade societies, the village council, or one of the chief positions – came only through acts of prudent judgement, beneficence, magnanimity, and generosity (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 26–64). By giving wealth to the penitent or the offended, others in the village would see one's virtuous characteristics, which was in the direct, long-term self-interest of each individual person who aspired to have more power and prestige. Additionally, giving away wealth in a beneficent way allowed individuals to accrue necessary supernatural powers as per existing religious beliefs. Thus, a Black Mouth (or other community member) would rationally make the trade-off between an immediate short-term cost of physical wealth and the expected long-term future gains in prestige, wealth, and spiritual power.

At first, it may seem as if the system of compensation would create perverse incentives to break social rules and feign penitence for compensation. Additionally, individuals could feign anger at fellow villagers or outside enemies visiting the village to extort compensation from the Black Mouths to ‘assuage’ their anger. Despite the possibility, the secondary historical literature does not indicate that such narrow opportunism was common. The records do indicate that the reputations of all villagers were well known by others in the village, and that a bad reputation would limit one's advancement through the age-grade societies, religious rites, and decision-making positions. The offender had to truly demonstrate why he was sorry and explain the situation to receive mercy and compensation if they were punished by the Black Mouths (Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 279). Due to the constant observance of the Black Mouths and the other age-grade societies, any villager who tried to opportunistically use the Black Mouths' compensation mechanism may be discovered as an untrustworthy person, undermining their long-term self-interest.

The traditional tribal governance structure began to erode due to epidemics and encroachment from white settlers (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 27–28). When the tribes were forced onto the Fort Berthold Reservation in the 1870s, the importance of the Black Mouth Society diminished. The federal government imposed new institutions on the tribes, and formal government policing replaced the traditional policing. The last members of the Black Mouth Society died in the 1950s, leaving the society inactive. In 2006, members of the Fort Berthold Reservation chose to revive the society, and 13 men became Black Mouths. Although the tribes now operate with a formal police force, the Black Mouths play a role in overseeing community events on the reservation (Rave, Reference Rave2006).

Institutional mechanisms of reliable policing in the Black Mouth Society

To avoid abuses of power, Mandan and Hidatsa villages took two basic measures to ensure reliable policing under the Black Mouths: institutional mechanisms on the front end mitigated potential abuses of power, and mechanisms on the back end punished abuses when they occurred.

Front-end mechanisms to mitigate abuses of power

Mandan–Hidatsa governance institutions included mechanisms for selecting reputable people who would wield policing power responsibly, reducing the chance of bad actors entering. Positions of power can provide scope for opportunistic behaviour, but effective selection mechanisms provided appropriate incentives for socially beneficial behaviour (see Allen, Reference Allen1998; Friedman, Reference Friedman1979). Two selection mechanisms ensured that the power vested in the Black Mouths was held only by individuals who could handle such responsibility prudently. First, Black Mouths were required to pass through the lower age-grade societies successfully and reach at least 30 years of age so that they could demonstrate their trustworthiness and good judgement. Second, becoming a Black Mouth required a unanimous (or near unanimous) decision by the incumbent Black Mouths and the more elderly men's groups, such as the Dog Society and Bull Society.

An individual's position in an age-grade society was a property right that had to be purchased, and a man in one society had to buy his place in a higher society. When the current Black Mouth members deemed that the members of the younger men's society (i.e. Half-Shaved Heads) were mature enough, the current Black Mouths would sell their positions (Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 313). Each cohort of age-mates in the Half-Shaved Heads would simultaneously purchase membership from the incumbent Black Mouths. The purchase of a position into a higher society had two components. One was collective in the sense that all members of the younger groups who wanted to advance contributed to the initial payment. The second was that, in addition to collective payment, each individual in the younger group would select one of the older men for a ceremonial ‘father’ to whom he would give special gifts (Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 225–226).

Once it was deemed appropriate for a member of the Half-Shaved Head Society to make a proposal to join the Black Mouths, there were specific expectations around the negotiation process. The buyers who wanted to join the Black Mouth Society would make a preliminary offer of smoking pipes and horses. However, one of the most important ‘prices’ was a ritual of offering one's wife. A buyer requested that the seller, as his ‘ceremonial father’, have intercourse with his wife. It is unclear how often the sellers accepted the offer. Lowie (Reference Lowie1913: 228) finds contradictory evidence, writing that some tribal members asserted that the sellers would ‘rarely exercised the privilege thus granted them’ for fear of negative spiritual repercussions, but other tribe members asserted that sellers ‘did in most cases avail themselves of the offer’.

The wife-offering custom was important because of the social value attached to marital fidelity and the religious beliefs that honour and power could be transferred through sex. One of the highest ideals of the Mandan and Hidatsa was marital fidelity, and many feminine social roles were only available to married women who had been faithful to their husbands (Capehart, Reference Capehart1980: 48). Within the religious belief system, an older man who was selling his position to a younger man could ‘bless’ the buyer through ceremonial sexual licenses with the buyer's wife (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 182–183). Even when a Black Mouth wanted to move to the next society (i.e. the Dog Society), he would offer his wife, as in other society purchases (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 198). The practice of a lower-ranking man offering his wife to a higher-ranking man allowed spiritual power to pass through a woman as intermediary, with sexual intimacy as transfer mechanism (Capehart, Reference Capehart1980: 50; Kehoe, Reference Kehoe1970). This practice was used whenever a man desired a blessing from an older man, in addition to the purchase of a position (Capehart, Reference Capehart1980: 51; Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 229).

The age requirement to purchase into the Black Mouths gave sufficient time for men to demonstrate restraint, good judgement, prudence, religious devotion, and generosity, which were expected of Black Mouths. It was not acceptable to move up quickly through the hierarchy of societies, and shortcuts were not allowed (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 193). Men who failed to meet the highest standards of each age-grade society did not advance.

The Mandan and Hidatsa had observed from neighbouring tribes that granting police functions to men of all ages yielded ineffective policing and abuses of power (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 188–189). As a result, they ‘were unwilling to entrust so important a matter as police functions to inexperienced youths. Instead, they reserved those functions for mature men who had been to war, had participated in numerous ceremonies, had given many feasts, and understood tribal history and values. In their advancement, they had eliminated the cowardly, the lazy, and the incompetent’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 192). Half-Shaved Heads were expected to have ‘sufficiently distinguished themselves in warfare, ceremonial activities and fasting, and shown evidence of good judgment’ so that they could be trusted to fulfil the social obligations and responsibilities of the Black Mouth Society (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 183). When Half-Shaved Heads would first attempt to buy into the Black Mouth Society, they were forced to wait at least 1 year, but often longer, which would give additional time to ascertain the qualities of each potential candidate.

The purchase of Black Mouth membership is a central aspect of the governing institutions. Purchasing membership promotes rather than undermines governance effectiveness because membership is net profitable, at least in the subjective valuation of the men who participate. Many young men are eager to join the Black Mouths because purchasing into the society is in their direct long-term self-interest. From a rational choice perspective, would-be Black Mouths are assumed to evaluate the costs and benefits of different alternatives. Purchasing membership in the Black Mouths is an investment, which involves upfront costs or sacrifices in anticipation of higher future benefits, which may include both material and spiritual benefits.

However, if a man were to purchase a place in the Black Mouths and then were to abuse power, he would have undermined his own investment because it would threaten his advancement to future male societies, the village council, or chief positions. Thus, buying into the Black Mouth Society signals the buyer's otherwise unobservable willingness to conduct himself properly because purchasing membership and then abusing power would be a net-negative investment in the long term. To serve as an effective signal, the price paid to become a Black Mouth necessarily exceeded the sale price of membership. Otherwise, a member earned a positive return on his investment even if his misbehaviour blocked him from advancing to the next age-grade society.

The second mechanism was that all Black Mouth had to agree to sell a position to a newcomer, and a single negative voice ended negotiations (Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 313). Additionally, a Black Mouth position would not be sold to younger men until there was a consensus among the older men of the Dog and Bull societies (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 184–185; Lowie, Reference Lowie1913: 276). The unanimous or near unanimous decision rule was in the direct self-interest of the incumbent Black Mouths and the more elderly men's societies because they would be under the purview of the new Black Mouths' authority.

The high threshold for admitting new Black Mouths reduced the chances that a ‘bad actor’ would be admitted because more opportunities for vetoing meant that more knowledge was involved in the decision-making process. Any decision-maker in the process who knew negative information about a potential Black Mouth could stop the process. Thus, the high decision-making costs reduced the potential external costs on the broader community (Buchanan and Tullock, Reference Buchanan and Tullock1962).

Back-end mechanisms for rectifying abuses of power

Any policing system will have some instances of abuses of power. Long-lasting governance institutions must, therefore, have mechanisms for punishing and rectifying abuses. As Bowers (Reference Bowers1963: 190) argues, ‘Although the Black Mouths collectively had such authority as the clans and households allowed them, at all times they were individuals in daily contact with the group, and the culture provided numerous checks to their authority’. Thus, the tribes' social institutions constrained the Black Mouths' discretion so that predation was minimal and allowed the system to work for centuries.

One of the most important constraints on the Black Mouths was social stigma. If an offender punished by a Black Mouth felt that the Black Mouth had acted in bad faith, the offender would make the injustice known to the rest of the community. The community would use gossip and ridicule as tools to undermine an abusive Black Mouth and erode the social legitimacy of his position, thus limiting his ability to further abuse power. Additionally, women who had been treated unfairly by a Black Mouth ‘might even go to considerable trouble to embarrass him publicly or dig up things in his past that he would prefer to forget’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 190).

Gossip seems to have been an effective check against Black Mouth abuse, but bad-faith actors may have faced incentives to spread gossip about a Black Mouth as a form of extortion. The secondary historical literature does not indicate that this was a common occurrence, and there are at least two explanations for it. First, villages were relatively small, and all members knew other members. It would become readily apparent if a person falsely ‘cried wolf’ too many times, leading to negative reputational effects. Second, the religious beliefs of the Mandan and Hidatsa people constrained the likelihood of widespread fraud. Individuals who acted without dignity were subject to spiritual penalties by a loss of supernatural power.

Informal institutions forced the Black Mouths to compensate individuals who were unjustly treated in police interactions. In particular, women used informal institutions to pursue justice against an abusive Black Mouth by sewing abusive Black Mouth a decorated shirt. Social protocols dictated that the Black Mouth would be obliged to give her his favourite buffalo-hunting horse in exchange. Such an obligatory payment usually constituted an extreme sacrifice for the Black Mouth (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 190). Ceremonies and personal status in the age-grade societies were critical to social life in these tribes, and abusive Black Mouths could be ‘denied property for use in a ceremony or be blocked in his ambitions by the aggrieved person's relatives who had social and ceremonial rights for sale’ (Bowers, Reference Bowers1963: 190).

Evidence indicates that individual Black Mouths who abused power were punished. Lowie (Reference Lowie1913: 279–280) recorded that when a fort was to be built in one of the villages, the Black Mouths ordered the women to help in the construction. A Black Mouth shot at one of his female relatives to frighten her as a joke. She thought this was an inappropriate use of the Black Mouths' authority, so she used social obligations to punish the offending Black Mouth. She made the offending Black Mouth a quill work suit, which obliged him to give her a horse in return, thus inflicting a cost on him for his abuse of power.

Since a position in the Black Mouths was a conspicuous social honour, shirking or abusing one's responsibilities would have had serious reputational effects. The institutional–social structure of these tribes in the age-grade societies meant that Black Mouths had to prove themselves as worthy, or they risked not advancing to high positions. Since many, if not most, tribal decisions were made with a high decision-making threshold, each Black Mouth had a strong incentive to fulfil his responsibilities well. In either case – shirking responsibility or abusing power – institutional mechanisms made it likely that the perpetrator would incur a significant cost, both in the immediate term and in the long term.

The socio-cultural connections between the Mandan and Hidatsa villages meant that violation by an individual Black Mouth would become known throughout the region. Families or clans moved between villages fairly frequently when governance in one village was not to their standards. If other villages learned about abuses of power, it seems unlikely that they would have accepted such a newcomer into their community. Thus, a predatory Black Mouth, for the most part, would have found it prohibitively difficult to find a new home where his reputation would not have been known. The power of social stigma seems to have provided strong enough incentives for most Black Mouths to avoid abusing their power.

Conclusion

Our analysis has two main implications. First, well-functioning self-governance, which includes reliable policing, is possible without a centralized state. The Mandan and Hidatsa tribes' pre-colonial governance system is a clear case of a context-specific self-governing community solving collective action problems related to potential opportunism and abuses of power. They effectively instituted a policing system that enforced collective decisions while also mitigating and punishing abuses of police power. This provides another piece of evidence, along with prior studies, that a centralized, top-down approach to collective action problems is not always and everywhere necessary.

Second, many Native American tribes have a long history of successful self-governance. The federal government's two-and-a-half centuries of subjugation and paternalism directed at Native American tribes disrupted these traditional governance systems. Today, the US federal government still has a heavy-handed influence in the governance of tribes across the country. Looking at traditional examples of governance shows that the sovereignty of Native nations could be expanded. Reforming tribal constitutions and allowing more self-determination at the tribal level could potentially allow effective forms of self-governance to be restored on reservations.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and four anonymous referees for useful feedback.