At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Spanish monarchy was in a secular crisis characterized by two principal issues: the imperial wars and the expenses required to cope with them. Since the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), the empire had prioritized its finances and found in the Spanish-American territories a place to implement the Bourbon reforms until the end of the century in order to improve the empire’s institutional and fiscal performance.

During the first decade of the 1800s, the urgency of these issues increased, powered by the troubled European monarchies’ relationships, which brought changed imperial alignments, with important consequences for America. In just a few years, Spain went from engaging in naval wars against Great Britain and frontier conflicts with Portugal (1796–1802) to plunging into a deep imperial crisis unleashed by the French invasion of 1808. These events had a powerful impact on Hispanic America, especially the Río de la Plata region. The region became isolated from the metropolis in 1803 with the supremacy of the Royal Navy. However, the viceregal capital successfully resisted English invasions in 1806 and 1807, financing instead through its own South American resources (military and fiscal). This experience gave way to a convulsive revolutionary process, accelerated by the monarchic crisis caused by the Napoleonic invasion and the subsequent fall of the Junta de Sevilla. This revolutionary process began in May 1810 and culminated in the independence of the United Provinces in 1816.

On October 16, 1802, the viceroys of New Spain, Lima, and Buenos Aires were notified of the serious situation of the monarchy’s finances because of the war. They were instructed to make “the greatest efforts to remit money” to the peninsula. Footnote 1 A reserved order with the same message was sent to similar recipients on January 17, 1804. Fiscal emergencies were not new to the Spanish monarchy, but they intensified during that decade in America and would only increase over the years. I demonstrate how, until the empire entered its final crisis, the main treasury of the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata employed various mechanisms typical of an old regime tax administration to obtain fiscal resources from the treasuries of the viceregal interior.

Until a few decades ago, part of the historiography dedicated to colonial tax studies emphasized the extractive and predatory nature of the Spanish tax system in America. According to this perspective, this character of the system was pronounced at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century, given the Crown’s urgent fiscal and military needs. Studies of economic divergence in the United States and Latin America emphasize the image of a voracious Bourbon treasury in contrast to the British Crown, with its representative institutions that limit the king’s discretion over political economy. Thus, a balanced British tax system would have been constructed to make economic development possible in the long term (North Reference North1990; North, Weingast, and Summerhill Reference North, Weingast, Summerhill, Mesquita and Root2000; Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001). The differences in these trajectories would only deepen in the heat of the imperial crisis, as the Spanish-American countries inherited a fiscal voracity based on a tradition of absolutist power and high institutional transaction costs for business that hindered economic development over the long run.

Current historiography has widely discussed views on the taxation of the Spanish Empire in America based on research that considers the negotiated nature of the American tax system between the monarchy and local elites. Researchers in the 1980s argued that the mere extraction of fiscal resources was a rather limited benefit of colonialism for the Spanish Empire (Klein and Barbier Reference Klein and Barbier1988).Footnote 2 More recently, studies of Hispanic American imperial taxation have stressed the redistributive character of the imperial fiscal system, which favored reducing costs for maintenance of the American colonies.Footnote 3 Before sending remittances to Spain, it was more important that the Crown reallocate resources between different regions in Latin American colonies (and the Philippines) to secure imperial borders and maintain social order.Footnote 4 This perspective emphasizes the necessary participation and benefit of Latin American elites in the management and distribution of fiscal resources (in the management of the so-called colonial situado, a transfer of fiscal resources from surplus treasuries to other royal treasuries), thus demonstrating the wide margins of action with which American oligarchies participated in the imperial treasury (Irigoin and Grafe Reference Irigoin and Grafe2006, Reference Irigoin, Grafe, Coffman, Leonard and Neal2013).

Thus, scholars have revised the dominant image of the monarchy and its tax system, which was based on negotiations between different powers to collect taxes, execute expenditures, and transfer resources from one region to another. This new image does not represent the Spanish Crown as an unopposed depredator of fiscal resources. Instead, it underlines the jurisdictional functioning of the imperial treasury and the difficulties for the Crown, even under the Bourbons, to centralize decisions and tax resources on both sides of the Atlantic with the resistance and autonomous institutional spaces of the Hispanic American elites and royal treasury officers.Footnote 5

However, from this perspective, a discussion topic revolves around the Crown’s negotiations and its incapacity to fiscally centralize. Recent historiography considers the negotiated government with local Spanish-American elites the necessary counterbalance for allowing the fiscal system to function, given limitations on the king’s discretion in managing finances (Irigoin and Grafe Reference Irigoin and Grafe2006; Grieco Reference Grieco2018). In contrast, the perspective associated with the neo-institutional model of Douglas North (Reference North1990) is that negotiations between the Spanish Crown and its subjects had negative effects. This perspective especially underlines the heterogeneous, noninstitutionalized, and corporate characteristics of fiscal negotiation that resulted in the monarchy’s incapacity for fiscal centralization, thus increasing financing costs and opening up opportunities to the king’s discretion, above all in taking out loans (Summerhill Reference Summerhill2008; Bohorquez Reference Bohorquez2022).

This research is inserted into the context of these studies to identify the capacity of the Royal Treasury of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata to collect surpluses from the regional treasuries in its jurisdiction beyond the situado of Potosí. Because the imperial treasury was constituted as a jurisdictional treasury of the old regime, the article presents an analysis of mechanisms of this type of system that allowed the Royal Treasury of Buenos Aires to attract surplus funds from the regional haciendas of the viceregal interior. Although historiography has identified the different resources that served to offset the fall of the situado of Potosí from the perspective of the Buenos Aires treasury (Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1982; Grieco Reference Grieco2018; Amaral Reference Amaral2014; Kraselsky Reference Kraselsky2016; Wasserman Reference Wasserman2017), I examine and reconstruct the extent to which transfers to the capital affected the main treasuries of the interior in relation to their incomes.

Next, I present some commentaries on the accounting books with respect to their importance as documents of the reconstruction of colonial accounting. I then analyze the volumes of the situado received in Buenos Aires from Alto Perú between 1780 and 1810. Finally, I examine the contributions of the interior haciendas and the mechanisms through which it sent funds to the capital during the last colonial decade (1800–1810).

The use of accountability documents and their possibilities

Like any language, the language of the accountant has its own peculiarities. TePaske and Klein (Reference TePaske and Klein1982–1990) researched the structure of all the royal treasuries of the Spanish fiscal system in America. Based on the documentation known as cartas-cuentas, this monumental examination rebuilt the incomes and expenses of each treasury, but with the accounting summaries’ own limitations, an issue that has generated many discussions among economic historians about the reliability of the information contained in these sources (Klein Reference Klein1984; Amaral Reference Amaral1984; Sánchez Santiró Reference Sánchez Santiró2015).Footnote 6 Although the studies based on these documents were very valuable in terms of showing general trends in tax collection, they were limited in their ability to appreciate the values of transfers between royal treasuries, in part given the particularities of the colonial accounting language of double and simple entry.Footnote 7 In this way, the possibility of estimating and characterizing aspects like transferred volume of resources, links between different treasuries and fiscal jurisdictions, and capacity of the principal royal treasuries to channel the regional surplus, among other questions, becomes problematic if working only with the database of Klein or the same sources. Precisely because many transfers between treasuries were recorded as entries and exits in each ramo, transactions can be identified only by examining the ledger and manual books together. For this reason, new works have retraced the reconstruction of the operation of ramos, the income and expenses of different treasuries, and special rents from accounting books, demonstrating the potential of such sources to estimate fiscal collections and transfers between treasuries and to engage in dialogue with other research on economic circuits and contribute to reconstructing regional economic performance (Wayar Reference Wayar2011; Sánchez Santiró Reference Sánchez Santiró2015, Reference Sánchez Santiró2016; Pinto Bernal Reference Pinto Bernal2015; Biangardi Reference Biangardi2016; Wasserman Reference Wasserman2017; Galarza Reference Galarza2019a, Reference Galarza2019b). All the values reconstructed here are based on fiscal primary documentation (major and manual books) to improve the precision in estimates of the different figures (e.g., tax collection, transfers).

The Royal Treasury of Buenos Aires and the arrivals of the situado of Potosí

In South America, the situado of Potosí is the case that has received the most attention, given the importance of silver production to Potosí and the impact of the injection of related resources on the taxation and economy of Buenos Aires (Klein Reference Klein1973; Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1982; Mira and Gil Lázaro Reference Mira, Gil Lázaro, Irigoin and Schmit2003; Cuesta Reference Cuesta2009; Wasserman Reference Wasserman2017). Studies underline the increasing flow of money to Buenos Aires from this situado after 1776 and until 1805, which then declined and finally disappeared between 1811 and 1813. In “Guerra y finanzas,” Halperín Donghi (Reference Halperín Donghi1982) identified a significant decrease in the volume of the situado potosino collected at the principal treasury of the viceroyalty, particularly between 1801 and 1810, and it had already started to decrease in previous years. Other research has confirmed this downward trend and tried to understand the reasons for the decline. Mira and Gil Lázaro (Reference Mira, Gil Lázaro, Irigoin and Schmit2003, 52) retrieve data prepared by TePaske and Klein (Reference TePaske and Klein1982–1990) from sources known as cartas-cuentas to assert a decreasing evolution in shipments of situado during the same period. The authors attribute the fall in shipments to a combination of an extended drought and a shortage of both mercury and workers in Potosí between December 1801 and May 1805, which hindered silver production. Footnote 8 Klein estimates that this decline spanned the entire eighteenth century, until 1809, with a brief rebound during the 1780s. Unlike Mira and Gil Lázaro, Klein (Reference Klein1998, 60) identifies the causes of the deterioration of Potosí silver production post-1780 as the influence of the European wars on trade and mercury supply.

However, along with the dropping income on behalf of the situado, the Buenos Aires treasury also stopped sending large money transfers to the metropolis. As Halperín’s research shows, the shipments to Spain declined from $8.6 million pesos between 1791 and 1805 to $162.000 pesos (in “hard silver”) between 1806 and 1810. In addition to this, and a point relevant to this research, the documentation studied by Halperín shows another offset to the arrival of lower volumes of situado: the increase of transfers from other treasuries in the interior of the viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, especially during 1806 to 1810. In fact, Halperín’s examination of the major books allows him to claim that the volume of funds contributed by the regional treasuries went from 151.762 pesos between 1801 and 1805 to 692.217 during the last five years of the colonial period, 1806–1810. The problem with the information thus presented is that the five-year organization makes it difficult to estimate the evolution of volume year by year (or by fiscal exercise). A major difficulty is identifying the origin of fiscal contributions from the different interior regions. As I demonstrate later, these values can be adjusted and corrected by consulting the accounting books of the different treasuries.

I reexamined the values of situado incomes at the Buenos Aires treasury between 1780 and 1810 to identify the ups and downs of the transfers. On the basis of the accounting books of the Real Hacienda of Buenos Aires, I adjusted the numbers of the situado—until now, estimated from cartas-cuentas by most other historians, except for Amaral (Reference Amaral2014). Footnote 9

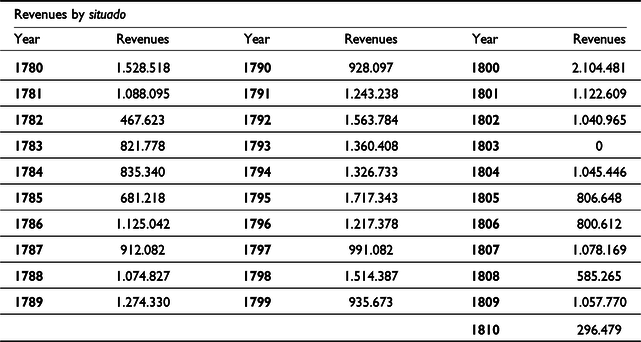

From a review of the accounting ledgers, I have identified the itinerary followed by the values entered on behalf of the situado potosino in Buenos Aires between 1780 and 1810. Constantly fluctuating, the 1790s presented an increase in the values entered in the Caja de Buenos Aires via Potosí (a secular trend, according to other historians) to show a clear decline in the volumes registered during the first decade of the nineteenth century.

As identified in Table 1, during the final years of the eighteenth century, the million pesos constituted a floor for the values of the situado; during the following decade, it became a ceiling. More importantly, for the purposes of this article, the fall began in 1801, when the amount declined from more than 2 million pesos to 1.1 million; it continued to fall until 1806. However, these numbers can be adjusted further, especially for income during 1806 and 1807. My research into the contributions of the treasuries of the interior to the viceregal capital allows me to establish that, in 1807, a large volume of funds was deposited in the Caja of Buenos Aires through promissory notes of individuals to be paid in the treasury of Córdoba (something similar happened in 1806). As I demonstrate, these funds were, in fact, part of the situado of Potosí that arrived in Córdoba, but the Royal Treasury of Buenos Aires managed to use them by libranzas.Footnote 10

Table 1. Incomes by situado according to accounting books of Buenos Aires treasury

Note: All values in tables are in silver pesos, each peso equivalent to ocho reales

Source: Accounting books of Buenos Aires royal treasury. Archivo General de la Nación, Sala XIII, Buenos Aires Royal treasury, major books 43-5-12(1780); 43-4-15(1781); 43-6-1(1782); 43-6-4(1783); 43-6-5(1784), 43-6-11(1785); 43-6-19(1786); 44-1-5(1787); 44-1-10(1788); 44-1-15(1789); 44-1-19(1790); 44-2-1(1791); 44-2-5(1792); 44-2-9(1793); 44-2-12(1794); 44-3-1(1795); 44-3-5(1796); 44-3-8(1797); 44-3-10(1798); 44-3-13(1799); 44-4-3 (1800); 44-4-4(1801); 44-4-8(1802); 44-4-11(1803); 44-4-15(1804); 44-4-19(1805); 44-5-7(1806); 44-5-14(1806); 44-5-18(1807); 44-5-21(1808); 44-5-26(1809); and Sala III, 39-3-3 (1810).

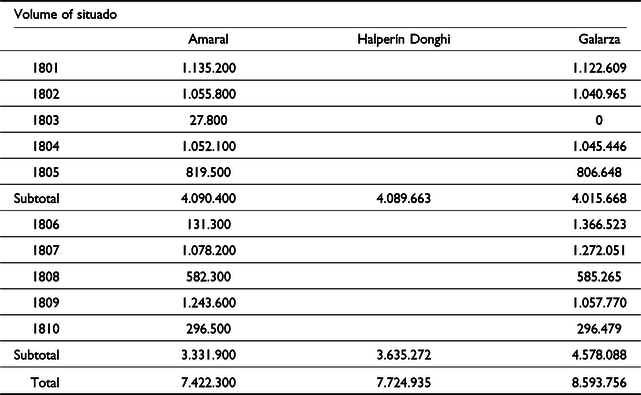

In 1807, about 561.000 pesos were entered into the ramo “Real hacienda en común” of the Buenos Aires treasury to be paid to third parties in the treasury of Córdoba. How did the Córdoba treasury cope with these commitments? The examination of the ledgers and accounting manuals of the two treasuries (Córdoba and Buenos Aires) allows us to reconstruct the payment circuit. By order of the viceroy, the Caja of Córdoba took a total of 193.000 pesos from the situado of Potosí led by the situadistas (which passed through Córdoba on its way from Alto Perú; Figure 1) on January 31 and August 22, 1807. In February 1807, 95.000 pesos in silver bars were transferred from Buenos Aires to Córdoba, likely part of the situado received the last year in the capital and spent on payments for money deposited in Buenos Aires during 1807. This amounts to a total of 288.000 pesos of the situado that the Córdoba treasury managed to collect to meet the commitments assumed in Buenos Aires. This implies that the funds from the situado managed by the viceroy treasury in 1807 were more than those registered in the Caja of Buenos Aires. Instead of the 1.078.169 pesos that historians have assumed, the total of the situado managed by the Real Hacienda’s treasury amounted to 1.272.051 pesos that year, including the resources brought to Córdoba.

Figure 1. Path of conductors of trade flows from Potosí to Buenos Aires. Map by Javier Kraselsky, based on a map found in the Archivo General de la Nación, Written Documents Department, map library IV-168. See Kraselsky (Reference Kraselsky2016, 224). I appreciate the author’s generosity in facilitating use of the map.

The management of part of the situado from Córdoba was not new; with the first English invasions of 1806, Viceroy Sobremonte settled in Córdoba and tried to establish his base of operations and the viceregal capital. On July 29 and September 29, 1806, part of the situado was given to the Córdoba treasury, which was in charge of its transfer to other haciendas (97.221 and 1.269.302 pesos, respectively). Part went to Montevideo for war and reconquest expenses (97.221 in gold ounces), and another part would be transferred to Santa Fe (16.000 pesos dobles) and Mendoza (10.000 pesos dobles).Footnote 11 Still, the bulk would be forwarded through cash carriers (situadistas) to Buenos Aires (950.000) for use in payments made by the Royal Treasury in Córdoba (for the viceroy’s salary and the soldiers and Cordovan militiamen destined to reconquer Buenos Aires).Footnote 12 The total contributed by Potosí to the viceregal treasury in 1806 amounted to 1.366.523.Footnote 13 The new estimated values of the situado corresponding to 1806 and 1807 are included in Table 2.

Table 2. Incomes by situado in Buenos Aires according to authors 1801–1810

Source: Amaral (Reference Amaral2014); Halperín Donghi (Reference Halperín Donghi1982).

As shown, the funds received by the situado between 1806 and 1807 were greater than historians have previously considered. A considerable portion did not enter Buenos Aires but Córdoba and was redistributed by order of Viceroy Sobremonte and disposed of in the context of the English Invasions. Especially throughout 1807, the treasury of Buenos Aires had the funds of the situado brought to Córdoba through promissory notes. Advancing funds to the Royal Treasury for metallic silver was a common practice, especially among traders, in the Río de la Plata (Gelman Reference Gelman1996; Grieco Reference Grieco2009). These operations highlight a few important aspects. For the Córdoba treasury, this meant establishing itself as a redistribution Caja for the resources of the situado, especially during 1806, when it executed an important part of the expenditures. But given that the royal treasury of Córdoba did not pay all the commitments in a timely manner, this implied a credit in favor of the Royal Treasury. The review of the accounting books (ledgers and manuals) of the Córdoba treasury demonstrates that, at least until 1810, a good portion of the funds received in Buenos Aires during 1807 to be paid in Córdoba had not yet been paid.Footnote 14 For individuals, there was the possibility of obtaining the silver of the situado from Potosí, from advancing funds in pesos dobles de cordoncillo in Buenos Aires (to meet the emergencies of the treasury), in addition to acquiring silver in Córdoba through agents.Footnote 15 This was a practice that allowed the benefits from currency arbitrage prizes to be privatized, albeit not without risk, since payments could take a long time to process

Last but not least, for the treasury of Buenos Aires, the use of promissory notes meant quickly raising funds to pay off military expenses. In this way, private individuals deposited a total of 465.000 pesos in the Buenos Aires treasury, an amount that should be paid in Córdoba for war outlays. The examination of the data (outputs) of Real Hacienda en común of the main treasury of the viceroyalty shows that it used these resources to pay institutions such as the navy in Montevideo or kept them in the capital’s treasury. Above all, using this mechanism in these circumstances granted the Caja of Buenos Aires the possibility of continuing to manage the resources of the situado even when, by order of the viceroy, funds had arrived at Córdoba. After the experience of 1806, when the distribution of situado and a significant part of the expenditure execution were under the authority of the Córdoba treasury, the money received by the Buenos Aires treasury by 1807 through promissory notes was used to more directly and quickly dispose of the Potosí funds, delegating the payment of the commitments assumed in the Córdoba treasury.

These findings demand a reassessment of the evolution of the situado during the first decade of the nineteenth century. As evident in Table 2, in the period 1801–1805 the situado suffered the biggest decline before recovering in 1806 and 1807. However, previously, specialized historiography had affirmed that the most important fall took place between 1805 and 1806 and in 1810. It had confused the funds introduced through promissory notes with contributions of the Córdoba treasury when those actually came from Potosí.Footnote 16 For the period 1801–1805, the differences between the estimations of Amaral (Reference Amaral2014) and Halperín Donghi (Reference Halperín Donghi1982) and my own research are because those authors recorded contributions from other Cajas in the interior within the situado.Footnote 17 Even if the amounts arrived together, the funds of other haciendas belonged to the surplus of each treasury and ramo.

If during the period 1801–1810 the income per situado reached 8.593.756 pesos, the decline in this period with respect to the previous decade amounted to 5.382.751 pesos. In the first five years of this period, however, silver arrivals from Potosí fell the most. How did the Real Hacienda of Buenos Aires manage to counterbalance this drop in income? What role did the funds of the regional treasuries of the viceregal interior play in the process?

The contributions of the regional treasuries between 1801 and 1810

A combination of resources and factors contributed to or allowed for the fall of the situado potosino beginning in 1801 and the rise in war-related expenditures with the English invasions. The most important factor was the consumption of accumulated funds in the ramos of the Real Hacienda (“Depósitos”; “Bienes de difuntos”) funds coming from Chile, transfers and loans from special rents (like tithes or tobaccos), and private loans through entities like the consulate and the cabildo (Halperín Donghi Reference Halperín Donghi1982; Amaral Reference Amaral2014; Kraselsky Reference Kraselsky2016; Grieco Reference Grieco2018).Footnote 18 The contributions of the Cajas of the viceregal interior were a factor, but a less important one. According to historians, the greatest contribution of the treasuries of the interior took place between 1806 and 1810, to help compensate for the presumed fall of the situado. But these figures confuse the contributions from Potosí during 1806 and 1807 with contributions originally from Córdoba. Research in the accounting books from different treasuries locates the biggest fall of the situado between 1801 and 1805, in line with the production crises in Potosí found in other studies, and its subsequent recovery to higher levels. In the following, I reconstruct the contributions of the royal treasuries of the viceregal interior of Río de la Plata to demonstrate that these shipments were more important during the first years of the century, when the situado fell and the monarchy repeated the requests for funds transfers. I also describe the different mechanisms through which the main treasury of Buenos Aires collected funds from the interior. Finally, I estimate the impact of remittances on the origin treasuries.

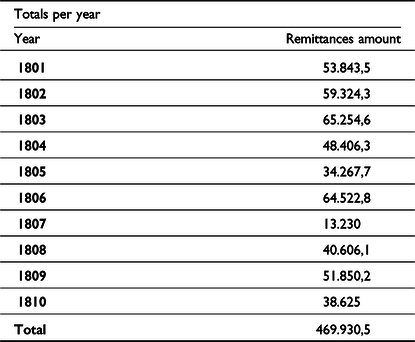

I have managed to identify all the entries of funds from the viceregal interior treasuries for the period 1801 to 1810 in the ramos that made up the Real Hacienda of Buenos Aires. Thus, it is possible to identify the amount that each regional hacienda contributed to mitigation of the effects of the fall of the situado during the period 1801–1810 while pinpointing the income collected by the Buenos Aires treasury year after year.

The reconstructed figures allow for corrections of the values estimated in the specialized historiography, demonstrating that the resources provided by the interior treasuries [without Alto Perú] were less than those previously assumed but show a different moment of arrival. Footnote 19 If we observe the total funds deposited on behalf of these treasuries during the period in which the situado declined (1801–1810), the value reaches 469.930.52 pesos (Table 3). This amount represented only 5.4 percent of the value contributed by the situado during the same period. If the amount references the values that the hacienda of Buenos Aires ceased to receive for this item compared to the income during the previous decade of the 1790s, that is, the 5.380.751 pesos in decline, then the resources contributed by the viceregal interior covered 8.7 percent of that total amount. Footnote 20

Table 3. Real Hacienda of Buenos Aires, incomes by treasuries of the viceregal interior (without Alto Perú)

I want to emphasize that the biggest surplus arrivals took place between 1801 and 1805, when the situado’s fall was more significant and the authorities of the royal treasury repeated their request for remittances as a result of imperial financial urgencies. During the following five years, this type of contribution became smaller as the situado potosino recovered. The main difference with the existing specialized research is this: the reconstruction of the circulation of situado only from the perspective of the Buenos Aires treasury meant that resources acquired through promissory notes were registered from Córdoba instead of Potosí. This led historians to believe that between 1806 and 1807, there was a greater decrease in the situado, which was compensated by loans from the Cabildo and other corporations together with an increase in contributions from the interior treasuries.

My research in the ledgers of the treasuries of Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Mendoza, and Santa Fe allowed me to reconstruct payment circuits, identifying and differentiating the funds that originated in the situado from contributions by regional treasuries. It also allowed me to understand how the Real Hacienda of Buenos Aires collected the surplus of these regional treasuries, which, between the years 1801 and 1805, served to feed the funds that were used to compensate for the fall of the situado. I explain this mechanism next.

Transfer mechanisms: An old regime treasury

In addition to the use of promissory notes to acquire funds from the situado received in Córdoba, the Royal Treasury of Buenos Aires had other mechanisms for acquiring resources under the jurisdiction of Córdoba. I identify two ways it acquired funds from Buenos Aires. First, it requested remittances with the help of carriers, who, in their journey from Potosí, added the surplus available in Córdoba to the flow rates to hand over in the viceregal capital. This was one of the main ways to send resources. The same was true in the cases of Tucumán, Salta, and the minor treasuries under the jurisdiction of Salta (Wayar Reference Wayar2011).

The other mechanism that allowed the Viceregal treasury to intercept funds was the recollection of the nuevo impuesto of the jurisdiction of Córdoba. Introduced during fiscal pressures with the Bourbon Reforms at the end of the eighteenth century, this tax affected the circulation of goods coming from the Northwest that crossed Córdoba to the coast (especially from Salta and Jujuy, at the south of Alto Perú, toward Santa Fe and Buenos Aires). The tax was created to cover frontier expenses, and it was under the jurisdiction of the cabildo of Córdoba city (which appointed a deputy for its collection) and the Royal treasury. The collection of the tax was divided between Córdoba and the Buenos Aires Customhouse, where a specific receiver, Domingo Hidalgo, took charge of the collection.

The funds from this tax in the Aduana of Buenos Aires were collected by the viceregal treasury from the surplus of the Córdoba treasury. The mechanism was simple: Domingo Hidalgo directly deposited part of the collection of the nuevo impuesto of Córdoba in the treasury of Buenos Aires. In return, the treasury of Córdoba transferred the equivalent value of its own surplus to a common fund, with which it paid the frontier expenditures. In this way, the treasury of the capital had access to the surplus of the Cordovan caja, drawing directly from the collection of the nuevo impuesto at the customs, thus avoiding the physical transfer of money and its risks. This also ensured the treasury would obtain the resources from Córdoba in a simpler and more efficient way instead of having to await the carrier’s arrival. For the treasury of Córdoba, the advantage was that it could use its surpluses to cover urgent frontier expenses, making the arrival of the nuevo impuesto collection from Buenos Aires unnecessary.Footnote 21 As seen in Table 4, this method of reimbursement represented 14 percent of the shipments from Córdoba to the main treasury of Real Hacienda in Buenos Aires.

Table 4. Funds from Córdoba treasury according to shipping mechanism

Source: Accounting books of Córdoba royal treasury. AGN, Sala XIII, Córdoba royal treasury (1800–1810) N° 573, 574, 575, 579, 581, 582, 584, 586-A, 587 and 589.

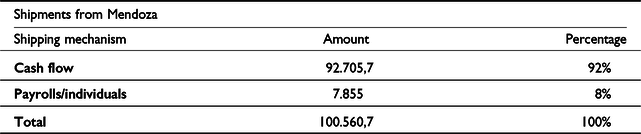

My research into regional treasuries in Mendoza and Santa Fe has allowed me to identify other similar mechanisms for transferring funds (Galarza Reference Galarza2019a, Reference Galarza2019b). In the case of Mendoza, the main mechanism for attracting resources by the Caja of Buenos Aires was the transfer of surpluses by treasury ministers. As Table 5 shows, the highest volume of transfers registered between 1801 and 1810 corresponds to this mode of shipments; a smaller percentage was made by promissory notes and private contributions in Buenos Aires charged to the Mendoza treasury (in 1809 and 1810).

Table 5. Funds from Mendoza treasury according to shipping mechanism.

Source: Accounting books of Mendoza royal treasury. AGN, Sala XIII, Mendoza royal treasury (1780–1810) N° 10-09-01; 10-09-02; 10-09-03; 10-09-04; 10-10-01; 10-10-02; 10-10-03; 10-10-04; 11-01-01; 11-01-02; 11-01-03; 11-01-04; 11-01-05; 11-02-01; 11-02-02; 11-02-03; 11-02-04; 11-02-05.

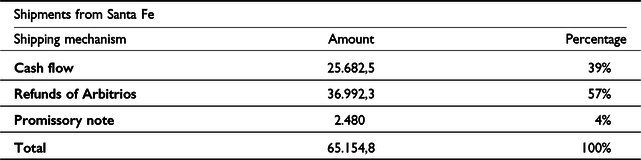

Meanwhile, in Santa Fe, the shipments of surplus originating from the regional treasury represented a lower percentage of the funds channeled to the capital (see Table 6). In this case, the main mechanism for capturing money was similar to that observed in the case of nuevo impuesto of Córdoba: the reimbursement of funds made from the caja de arbitrios of the cabildo of the city of Santa Fe to the Caja of Buenos Aires.Footnote 22 Furthermore, a third mechanism was direct remittance of funds from smaller fiscal jurisdictions that made up the Royal Treasury of Santa Fe, especially from the receivers of alcabalas of Entre Ríos (the villages of Concepción, Gualeguay, and Gualeguaychú) and from the villages of the former Jesuit missions that sent resources to the aduana in the capital without going through the hands of the royal officers of Santa Fe.

Table 6. Funds from Santa Fe treasury according to shipping mechanism

Note: We must point out that, since 1808, the excise tax fund collected in the port of Las Conchas was integrated as a ramo ajeno in the treasury of Buenos Aires, which reduced the amounts of refunds since the Buenos Aires treasury managed to get hold of these resources directly collected in Las Conchas. The amount of this collection between 1808 and 1810 extended to a total of 45,000 pesos deposited directly in the treasury of the capital. Thus, the total collected by this item for the period 1801–1810 amounted to 82,192 pesos.

Source: Accounting books of Buenos Aires royal treasury. For Santa Fe, see AGN, Sala XIII 31-04-05, “Propios y arbitrios de Santa Fe, 1777–1790” and Sala IX 03-10-05 “Propios y arbitrios de Santa Fe 1802–1808.”

Regarding refunds by arbitrios, as historians have reconstructed in previous works (Galarza Reference Galarza2019a), this mechanism allowed the Buenos Aires treasury to manage to retain part of the collection of this tax collected in the Port of Las Conchas, under the jurisdiction of the Caja de Buenos Aires. As these funds belonged to the Cabildo of Santa Fe and were used to pay expenses to the imperial frontier (especially military ones), the Buenos Aires treasury ordered the royal officers of the Santa Fe regional treasury to send their surpluses to the cabildo of Santa Fe to discount, in turn, the equivalent amounts of the arbitrios collection in Las Conchas and integrate them into their own coffers. In practice, this compensation mechanism was identical to the nuevo impuesto and served to channel surpluses from the treasury of Santa Fe to the treasury of the viceregal capital, avoiding the physical transfer of money.

These reimbursements represented 57 percent of funds that the Buenos Aires treasury managed to collect from the regional treasury of Santa Fe during the first decade of the 1800s, constituting the main mechanism for raising funds. The remaining volume of resources was channeled through transfers of remittances, especially in 1802, as I explain in detail in the next section. The three cases show the diversity of mechanisms implemented by the administration of the Royal Treasury of the viceroyalty to collect resources or surpluses from the royal treasuries of the interior.

With reference to the regional distribution of these contributions, the inputs realized by Córdoba stand out, followed by Mendoza, then Salta and the treasury of Santa Fe (Table 7). If the organization of resources is established based on the fiscal jurisdictions and their contribution to the main treasury of the viceroyalty, then the Córdoba treasury leads, with 33 percent, while the Salta treasury is a close second, reaching 27 percent of the total, leaving the Cuyo region with the smallest contribution of 23 percent. Meanwhile, the coastal region, led by Santa Fe, reaches 18 percent with a figure close to 83.000 pesos. Moreover, the Cajas of Paraguay and Montevideo demonstrate their character as recipients of funds from Buenos Aires (especially the latter) (see Table 8). Footnote 23

Table 7. Caja de Buenos Aires, incomes from interior treasuries 1801–1810

Table 8. Caja de Buenos Aires, incomes from interior by fiscal jurisdiction, 1801–1810

If in Buenos Aires the funds for moderating the fall of the situado of Potosí are consistently about 8.7 percent of the total resources, this pattern changes when we focus on the treasuries of the interior. The shipments from the regional treasuries of the viceroyalty changed composition throughout the decade, showing in different years the prominence of some treasuries that concentrated greater volumes of remittances. Although remittances from the interior were not voluminous for Buenos Aires, they were significant from the point of view of the income structure of the haciendas in the interior.

As Table 9 shows, the average percent was greater in the treasuries of Córdoba and Mendoza and smaller in Santa Fe. In this case, it was influential that part of the collection of arbitrios was placed directly under the jurisdiction of the Buenos Aires treasury in 1808 (and that the amounts collected were entered directly in the Caja principal). However, the amount of funds acquired by different mechanisms of the Royal Treasury of the viceregal capital was more important for the origin treasuries than the Buenos Aires treasury. It should be noted that in the period 1801–1805, which we emphasize as the greater fall of the situado of Potosí, the pressure that the remittances exercised on the incomes of the interior treasuries of Mendoza, Santa Fe and Córdoba was greater than the period from 1806-1810. In the first case, the average increased to 64 percent over the effective incomes of the Caja. As a result of these, for example, the Mendoza coffer went from registering a total of 37.399 pesos of remaining cash at the end of 1802, to having 8.805 pesos for the same item at the end of 1803. During that year, the funds acquired in June and December surpassed the previously accumulated funds in the coffers of the regional treasury.

Table 9. Shipments to Buenos Aires as percentage of incomes in regional treasuries of Mendoza, Santa Fe and Córdoba, 1801–1810

A: effective incomes of the treasury // B: funds collected by/send to Royal Treasury of Buenos Aires. Note: The column entitled % B/A represents remittances sent to Buenos Aires as a percentage of the annual income of the originating treasury.

A similar process had taken place in the Santa Fe treasury. Particularly in 1802 and 1804, the cash flow to the capital was very important. The shipments registered in 1802 originated in the superior order of the royal visitor Diego de la Vega to remit the totality of the treasury surpluses to the capital, in line with the requirements from the metropolis. This value amounted to 22.417 pesos, which, when compared to the effective income in the Santa Fe treasury in 1802 ($12.185), was almost twice as much. Undoubtedly, this also influenced the consumption of accumulated funds in the regional treasury, which at the beginning of 1802 reached $33.445 in “hard silver” and at the end of the same year only 21.044 pesos. The average pressure over the incomes between 1801 and 1805 rose to 23 percent.

The case of Córdoba shows a larger and more persistent pressure of remittances over incomes during the period 1801 to 1804, before a decrease in 1805. These affected the remaining money available in the coffer of the treasury, which had already seen the fall of metal values from 22.880 pesos in December 1803 to 12.861 pesos one year later. The average pressure on effective incomes during the period 1801 to 1805 amounted to 60 percent, demonstrating the impact of the remittances in the treasury. Here, too, the needs or demands of the Royal Treasury facilitated the mobilization of resources.Footnote 24

In the next years, the remittances to the capital decreased. In line with the possibility of the managed funds of the situado, at the end of 1806 the remaining money available in the coffers of the Córdoba treasury increased to 46.000 pesos. But during 1807, having to face the commitments of promissory notes ingresses in Buenos Aires made the cash in the treasury at the end of this year close to 18.000 pesos and would continue to decline especially between 1809 and 1810.

Finally, Wayar (Reference Wayar2011, 24) mentions the Salta case and estimates 55 percent in average volume of shipments to Buenos Aires between 1784 and 1808 which was calculated not in relation to treasury income, but in relation to the remaining cash available in the treasury.Footnote 25 However, Wayar states that it was a decreasing percentage considering the immediately previous period (88 percent).

Conclusions

The Royal Hacienda of the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata attempted to obtain the surplus of the interior treasuries, according to the needs of the treasury. During the period 1801–1805, when the hacienda needed resources, the funds of the situado from Potosí fell sharply. However, the treasury of Buenos Aires could obtain the surplus of the regional treasuries, through different mechanisms. The royal visitor of the hacienda, Diego de la Vega, was key to channeling the surplus of the treasuries of Santa Fe, Córdoba, and Mendoza, especially between 1802 and 1803. During 1803, the were no revenues from the situado in the Caja of Buenos Aires. Notwithstanding, sending remittances was a mechanism that worked regularly, especially in the cases of Mendoza and Córdoba. So, the contributions of the interior treasuries between 1801 and 1805 were more important than the historiography has supposed.

The other important mechanism for channeling resources from the treasuries to Buenos Aires was the refunding of taxes of Santa Fe and Córdoba. In the first case, the refunds of the arbitrios of Santa Fe city and its form of recollection constituted a mechanism that allowed the treasury of Buenos Aires to recollect an important volume of funds during those years. Something similar was put into practice in the jurisdiction of Córdoba, where the division of the collection of the nuevo impuesto meant that customs in Buenos Aires had resources of Córdoba available to send quickly to the coffers of the treasury of the capital. This allowed part of the surplus of the treasury of Córdoba to be received in Buenos Aires through reimbursements, avoiding the transfer of money. The distribution of resources involved communication across various fiscal jurisdictions including the municipality of the cities of Córdoba and Santa Fe, the regional haciendas, and the viceroyalty, which was represented by the Buenos Aires treasury.

Historians have traditionally attributed the low revenue of the situado in Buenos Aires in 1806 and 1807 to a decline in shipments from Potosí. However, the situado shipments remained steady, but were diverted to Córdoba rather than directly to Buenos Aires. During 1806, the Córdoba treasury was able to manage and distribute these funds, including sending funds to Mendoza, Santa Fe, Montevideo, and Buenos Aires. This meant an improvement in the money available in the coffers of Córdoba at the end of 1806. By 1807, that situation ended. Although the situado of Potosí arrived at Córdoba again, the treasury of Buenos Aires took resources of individuals through promissory notes to pay the Cordovan treasury. In this way, the main hacienda of the Viceregal was able to manage an equivalent volume of funds faster, without having to wait for the money to arrive. Therefore, because in 1806 only 950.000 pesos from the total of 1.269.302 pesos of the situado that arrived at Córdoba were resent by carriers to Buenos Aires, the utilization of promissory notes facilitated direct access for the Buenos Aires treasury to the funds of the situado that arrived in Córdoba in 1807.

The participation of individuals as moneylenders through promissory notes was not new, but in this case expressed the competition between both treasuries (Córdoba and Buenos Aires) to manage the funds that came from Potosí, after the experience of 1806. The cost to the Real Hacienda was the privatization of the money prize, but the risk to the individuals was that payments could be delayed.

From 1806-1810, the income that came from Potosí improved, and the contributions from the other interior treasuries were less than the historiography today indicates. However, the mechanisms to extract surplus included reimbursing taxes between Córdoba and Santa Fe and the treasuries’ remittances through carriers.

All those mechanisms allowed the Royal Treasury of the Viceroyalty to obtain resources from the interior treasuries. Although the volume of these funds was minor for the income structure of Buenos Aires, they were important for the origin of regional haciendas. We proved that in the main treasuries of the interior, such as Mendoza, Santa Fe, and Córdoba, the volume of funds finally collected by Buenos Aires represented important percentages of the real incomes of these treasuries. In some years, the amount of these resources implied a strong reduction of the available money in each regional coffer.

We conclude that all of the situations described here show the good functioning of the Royal Treasury, which is far from the traditional view characterized by disorder and corruption. This contradicts the idea that the interior haciendas had large margins of autonomy. This autonomy was always in dispute. The development of different ways of channeling resources allowed their arrival in Buenos Aires, putting pressure on the interior haciendas, especially in times of urgency for the imperial treasury, during the first five years of the nineteenth century. But the objective of extracting a greater volume of funds did not take place by a process of standardizing and verticalizing the fiscal scheme under the Bourbon reforms. Nor were the reforms carried out by a resource-hungry Crown that set its own terms without regard for its subjects. The analysis shows that the circulation of funds between treasuries was developed in a framework of tension, disputes over jurisdictions, and mechanisms of money extraction that were typical of an old regime hacienda. Where some earned little, others earned a lot, and everyone had to give up something to protect their own interests. However, this did not mean that the system was dysfunctional; it may not have been efficient, but it was effective.

The empire worked, sending requests for resources to all corners of the viceregal treasury and exerting strong pressure on the regional treasury accounts, through the old regime mechanism. Whether or not these funds were later sent to the metropolis (and to what extent) is another story.

Acknowledgments

I would like to make special mention of Katherine Esterl, whose assistance with the proofreading was invaluable.