Only around 36% of children in Glasgow were breast-fed at 6–8 weeks in 2005, with rates varying from 16% in disadvantaged communities to 61% in more affluent areas1. Knowledge about disparities in breast-feeding coupled with a desire to address inequalities in health resulted in the launch of the Greater Glasgow NHS (GGNHS) Breastfeeding Strategy in 1999 and its updating in 2003. One of the objectives of the strategy was to adopt and monitor adherence to the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes2. The WHO Code aims to protect and promote breast-feeding and ensure the proper use of breast-milk substitutes (BMS). The Code does not ban BMS but sets out how companies are permitted to market them. The Code applies to the marketing of BMS, i.e. infant formula and follow-on formula, as well as any food or drinks marketed for infants < 6 months of age in a way that undermines breast-feeding (Box 1).

Box 1 – Key points of the World Health Organization's International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes with respect to primary-care staff and facilities

● No promotion of infant formula and bottles or teats or other products within the scope of the Code

○ Facilities should not display products, placards or posters or distribute materials except for informational and educational materials that do not refer to a proprietary product ○ Logos of companies that manufacture breast-milk substitutes (BMS) are viewed as promotional material

● No provision of free or subsidised supplies of BMS and other products unless for evaluation or research

○ All products should state the superiority of breast milk and should have appropriate instructions for use along with a warning about inappropriate preparation

○ BMS must be clearly labelled and should not idealise artificial feeding

● No inducements to promote products

● Companies to provide only scientific and factual advice

● Any funding must not create conflicts of interest

A surveyReference Britten and Broadfoot3 conducted in 2000 reported that approximately 68% of health visitors used BMS company materials. Such materials promote BMS and therefore undermine breast-feedingReference Wright and Waterston4; thus GGNHS took the additional step of prohibiting contact between health-care professionals and BMS company personnel. Relevant information from these companies is distributed to primary-care staff via an Infant Nutrition Information Group (INIG). The INIG is a multidisciplinary group which has a special interest in infant nutrition. The group aims to equip all health professionals with updated and factual information on the subject of infant feeding. Information is distributed in the form of regular newsletters.

The purpose of the present audit was to identify the degree of contact between primary-care staff and BMS company personnel and the degree to which facilities and primary-care staff complied with the WHO Code, two years after the GGNHS guidelines were introduced.

Methods

The audit was designed by the WHO Code subgroup, a multi-professional steering group comprised of individuals who had experience and knowledge of the Code, and was conducted in two stages: a staff survey and an audit of NHS (National Health Service) facilities. Ethical approval was obtained from the Greater Glasgow NHS Primary Care Division.

Stage 1 – staff audit

The audit aimed to explore staff contact with BMS companies, distribution and use of BMS company materials, incentives offered and to elicit staff views on the Code. The staff audit form was adapted from the WHO Code compliance questionnaire and protocol5 to include all potential violations of the GGNHS guidelines and was designed to take approximately 10 minutes to complete. The audit form plus a stamped addressed envelope were sent to all health professionals with an infant feeding remit within the Greater Glasgow Primary Care Division in May 2005. This included health visitors, health visitor support staff, community midwives, dietitians, nurses and general practitioners (GPs). Completion of the form was voluntary and anonymous, and one reminder was issued.

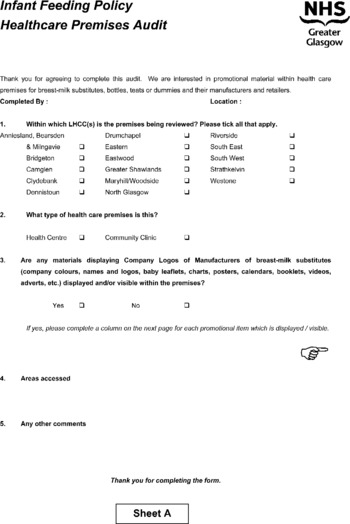

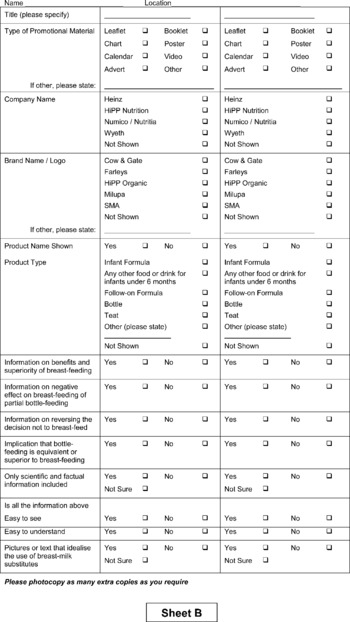

Stage 2 – facilities audit

Eligible premises were all clinics and health centres run by the Primary Care Division. Half of these 58 premises were randomised for inclusion using a random numbers table. After sampling, any premises found to be no longer in use was excluded and not replaced. At the time of the audit one LHCC (local health care co-operative) in Glasgow was accredited in the UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund) Baby Friendly Community Award; Primary Care Division premises in this area were deemed eligible but in the event none was randomised to the audit group. Permission to access each premises was obtained by the audit coordinator about 1–2 weeks prior to the audit from the LHCC manager, none of whom refused. Specialist health visitors were specifically trained to conduct ‘walking tours’ of facilities with the assistance of a member of staff from the facility. Areas visited included community areas, health visitors' rooms, health promotion material stores, pharmacy areas and child health clinics, but excluded GP consulting rooms or waiting areas as these were not managed by GGNHS. An audit sheet, which was designed and piloted for this study, was completed at each visit. This identified materials which might promote BMS, e.g. leaflets, posters or calendars, or which might display either a BMS company name or logo. It also identified infant formula and feeding equipment and assessed compliance of these with the WHO Code (see Appendix).

Data analysis

The data collected were analysed using SPSS for Windows and descriptive statistics and frequencies. The staff audit form also invited respondents to comment freely on the audit or breast- or bottle-feeding. Comments received were tabulated and used to highlight some of the issues pertinent to the respondents.

Results

Stage 1 – staff audit

A total of 669 forms were returned from the 1078 distributed, giving an overall response rate of 62% although this varied by professional group (Table 1). Only 32 respondents ( < 5%) had been visited by BMS company personnel in the previous six months (Table 2). These visits tended to be unsolicited with only three visits being requested. The main staff groups with contact were dietitians (22%) and health visitor staff (9%). The main purpose of these visits was to provide product information, educational updates or infant nutrition support.

Table 1 Response to staff audit

Table 2 Reported staff contact with company personnel (staff audit)

BMS – breast-milk substitutes.

Only 48 (7%) respondents reported receiving advertising through gifts (stationery, diary covers, calendars/posters, developmental toys, meals, coffee and money-off vouchers) or funding (to attend conferences), but 137 (20.5%) respondents reported receiving a range of literature – providing information on BMS products, weaning, breast-feeding, becoming a dad, sleep, toilet training and behaviour management – from BMS manufacturers.

Three respondents reported that they had been given free BMS, one of which was described as ‘specialist’, and six reported being offered free feeding equipment. No offers of other food or drinks for babies were reported. Only one respondent stated that the free sample was given to a pregnant women or mother.

Comments from primary-care staff

Respondents were invited to provide ‘any other comments you may have with regard to this questionnaire or breast/bottle feeding’ and 133 comments were received. These highlighted a range of issues, but 49 comments addressed the need to be able to provide support for all mothers and up-to-date and relevant information to bottle-feeding mothers.

‘I understand the extreme importance of promoting breast-feeding but do feel we should be kept up-to-date on formula milk by their suppliers to have a broader knowledge to pass on to bottle-feeding mothers.’ (Respondent 116)

A number of respondents stated that most mothers in their area of practice bottle-fed and deserved good information. Most commenting on this appeared to think that information from BMS manufacturers was important and essential for bottle-feeding mothers, although several stated that nutritional updates or independent information from the Division, LHCC or Health Board should be provided. The increasing number of ‘specialist’ milks available was mentioned and the only information on these milks appeared to come from BMS companies. For some, contact with ‘specialist’ milks companies was the only contact with BMS companies and seemed to be considered outwith the remit of the WHO Code.

A number of respondents noted the importance of women's choice or of respecting parental decisions.

‘I think there needs to be a balance of respecting parental choice in breast- and bottle-feeding. I feel up-to-date knowledge in milk products as well as updating knowledge re breast is essential in treating patients fairly.’ (Respondent 228)

There also seemed to be the view that BMS company advertising would not affect breast-feeding behaviour, and that once a woman had decided to bottle-feed it was pointless to prevent her from accessing BMS company leaflets, literature or supplies of reduced-price milk.

‘The vast majority of my clients formula-feed they are entitled to receive current, safe advice re formula-feeding. Contact with reps helps professionals to stay informed about changes but does not mean that we are actively encouraging women to stop breast-feeding to embark on formula […] Clients want information about formula because they are using formula […] Not having information to give her about formula will not restore her to breast-feeding.’ (Respondent 214)

Some expressed concerns regarding the promotion of breast-feeding especially at the expense of bottle-feeding mothers, stating that mothers who could not breast-feed were made to feel guilty about bottle-feeding. A minority of respondents voiced concerns that breast-feeding promotion had ‘gone too far’ and described advocates as ‘mafia’.

A minority who commented on the WHO Code stated a belief that the WHO Code may prevent correct information being available to bottle-feeding parents and so increase the risk of dangerous bottle-feeding practices.

Stage 2 – facilities audit

A total of 27 community health facilities from 11 LHCCs were randomly selected to take part in the audit. This comprised 13 health centres and 14 community clinics. None of these facilities were UNICEF Baby Friendly Community Award (BFI)-accredited.

Twenty-six non-compliant materials (weight conversion charts, posters, age calculator, vaginal examination guide, desk tidy development pack, baby rice, booklets and leaflets) were found in nine (33%) of the 27 premises. Each of these premises had 1–6 materials in a range of locations: in the general clinic area (10), child health/baby clinic (4), health visitors' rooms (4), staff office (3), breast-feeding room (2), corridor (2) or main reception (1).

The 26 non-compliant materials advertised BMS by displaying a company name (10), logo or brand name (24), or a product name (14), or combination of these. Ten items gave information on the benefits or superiority of breast-feeding and seven on the negative effects of partial breast-feeding. On only one item was the information scientific or factual, and six implied bottle-feeding was equivalent or superior to breast or idealised BMS (10).

Discussion

There have been reports from a range of countries of the failure of health-care facilities to comply with the WHO CodeReference Taylor6, 7. These reports have also served to highlight the changing marketing tactics of BMS companies. This is the first audit of compliance with the WHO Code in UK primary care and of the additional step of a ban in contact between health-care staff and BMS company representatives.

The minimal and mostly unsolicited contact between community health-care staff and BMS company personnel, which compared positively with the 2000 surveyReference Britten and Broadfoot3, demonstrated the effectiveness of the GGNHS Breastfeeding Strategy. A shift in practice regarding the distribution and usage of BMS materials was also evident, with only one respondent stating that they had passed BMS company information to a pregnant or breast-feeding woman compared with 20% in 2000. Around 20% of respondents had received literature from BMS companies, which compares favourably with the rate in Poland in 1998 but less well with that in Dhaka at the same timeReference Taylor6. The presence of BMS materials in one-third of health-care premises was more common than contact between BMS staff and respondents, and although some were found in non-public areas, most were in areas accessed by the general public. Of concern was the number of non-compliant materials found in child health clinics and breast-feeding rooms.

The staff sample audited was a voluntary sample and it is possible that only the most compliant individuals or those more supportive of breast-feeding may have chosen to respond. However, several of the comments received indicated that this was probably not the case.

Although the response rate of 62% is acceptable for a postal questionnaire it should be noted that this varied by professional group, with the highest response rate among health visitors and health visitor support staff but rates of only around 50% for other groups. It is therefore not possible to generalise the results of this audit to all members of these professional groups.

The random selection of health-care premises provided an unbiased sample, but was limited slightly by the inclusion of only those premises managed by the Primary Care Division. It is also possible that, in the time between seeking permission from the LHCC manager to visit and completing the audit, non-compliant materials may have been removed. However, it seems unlikely that the managers would have been sufficiently familiar with the WHO Code to know which materials were in fact non-compliant. A strength of the study was that the specialist health visitors who conducted the audit, although involved in writing and disseminating the guidelines, were not based in any of the premises audited and would not have given preference to any specific facility.

Some staff expressed a need to both protect mothers in their caseloads from unsafe practices and to support parental choice regarding infant feeding. This reflects two papersReference Cloherty, Alexander and Holloway8, Reference Simmons9 published in the UK exploring health professionals' beliefs about their role in promoting and supporting breast-feeding. In these studies staff believed they had a duty to protect the mother from tiredness, distress and/or guilt (e.g. by making it easier for her to give up breast-feeding) and that the mother had the right to bottle-feed should she choose. There is published evidence that breast-feeding mothers experience conflicting advice and feel inadequately supported by health professionalsReference McInnes and Chambers10, but the experiences of bottle-feeding mothers have received little attention and would be worth exploring.

The GGNHS had identified contact with BMS company personnel as undermining to the promotion and protection of breast-feeding and had thus taken the unusual step of restricting contact. However, BMS advertising was still received regularly and while many respondents stated that this was discarded, this was not true for all individuals. Of interest were the strong beliefs voiced by some staff stating that the mothers in their caseloads needed information about BMS, that company information was acceptable or at least better than no information, and that often BMS company information was the most up-to-date information available. Some acknowledged that they would prefer independent information but, despite the availability of the infant feeding guidelines11 and the INIG, seemed to believe that this was not available. Resistance to change is a well-known phenomenon in society and within the heath servicesReference Proctor and Renfrew12. This audit was not able to determine whether the negative comments were as a result of a temporary response to change or a reflection of the deeper attitudes of health professionals. There was a suggestion that respondents believed they were personally able to ‘sift the psychological sell from the facts’ and therefore may have viewed the ban on contact as professionally restricting. Beliefs in an immunity to advertising pressures have been identified in relation to doctors' prescribing habits and contact with pharmaceutical representativesReference Orlwoski and Wateska13–Reference Halperin, Hutchison and Barrier16, despite the fact that several studies have also shown changes in behaviour related to contact, gifts or sponsorshipReference Orlwoski and Wateska13, Reference Chen and Landefield17, Reference Wazana18. Advertising directed at mothers has been shown to affect breast-feeding durationReference Howard, Howard, Lawrence, Andresen, DeBlieck and Weitzman19; however, the impact of BMS advertising or contact on the provision of breast-feeding support by health professionals has not been adequately explored. Further work would be required to identify the full impact on primary-care staff and to identify what the NHS can do to support staff in resisting the use of such materials. It might be helpful to assess whether training and education rather than simply changing the rules would be required.

Facilities which are BFI-accredited must conform to the WHO Code. Although no BFI-accredited facilities were audited, the facilities in the BFI-accredited LHCC are audited annually and no violations have been found in the three years since accreditation (personal communication). It is likely that the BFI offers an important strategy in the promotion and protection of breast-feeding.

Conclusion

The introduction of a strict infant feeding guideline appears to have resulted in much reduced contact between primary health-care personnel and BMS company personnel, although BMS materials in health-care premises remained fairly common. However, the bottle-feeding culture still prevails in Glasgow; primary-care staff perceived contact with BMS companies as necessary for information purposes and some staff expressed considerable negativity about efforts to discourage use of BMS in their client group.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This research was funded by Greater Glasgow NHS Board.

Conflict of interest declaration: There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authorship responsibilities: R.J.M. wrote the original Greater Glasgow NHS Board report and drafted this paper; C.W. participated in the design of the audit and made substantial comments on the drafts of this paper; S.H. managed and designed the study and commented on drafts of this paper; M.M. participated in the design of audit forms, sampling techniques, data analyses and commented on drafts of this paper.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge the work of Alasdair Buchanan, Clare Walker, Gale McCallum, Heather Mackenzie, Helen Mactier, Karen Richards, Linda Wolfson, Lorna Barr, Lorna Hood, Marion McPhillips and Tricia Mostyn of the WHO subgroup of the GGNHS Breastfeeding Strategy Group in implementing the policy and planning and executing the evaluation, as well as commenting on drafts of the subsequent report. We would also like to thank the Mentors, including Margaret Swan, Liz Teiger, Michelle McCarthy, Kary O'Brien and Anne Evans, who conducted the health facilities audit.

Appendix – audit sheets used in the study