We thank Professor Kawada for his careful reading of our paper. He raises a number of issues that we address here. First, it is important to recognise that, while we used the same study (the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, ELSA) in each of the papers he describes, Reference White, Zaninotto, Walters, Kivimäki, Demakakos and Biddulph1,Reference White, Zaninotto, Walters, Kivimäki, Demakakos and Shankar2 we asked very different questions of the data.

In the first paper, Reference White, Zaninotto, Walters, Kivimäki, Demakakos and Shankar2 we were interested in whether depression symptom severity, across the full range of scores measured on a single occasion, was related to later risk of all-cause mortality. If mortality effects are seen in people with mild-to-moderate depression, this could potentially point to the need for treatment at lower levels than is currently the case. Wishing to test whether the dose–response association we found for psychological distress (a combined measure of depression and anxiety) and all-cause mortality in the Health Surveys for England – Scottish Health Surveys collaboration was replicated using a depression-specific inventory, Reference Russ, Stamatakis, Hamer, Starr, Kivimäki and Batty3 we used an administration of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) during wave 1 of data collection in ELSA. On relating those scores (higher score indicated greater depression severity) to mortality experience over the following 9 years, after basic statistical adjustments, there was a stepwise effect that, as Kawada indicates, seemed to plateau in people reporting the most severe symptoms.

In the second paper, recognising that symptoms of depression tend to be, as Kawada points out, time-varying, Reference Judd and Akiskal4,Reference Judd, Akiskal, Maser, Zeller, Endicott and Coryell5 in order to better capture depression exposure we capitalised on the serial measurements made over 4 waves of data collection (8 years) in ELSA, which is rare in population-based studies. We found that the number of waves a study member was denoted as a ‘case’ (based on a score of ⩾3 on the CES-D) was positively associated with deaths occurring after the final wave of data capture. Again, we found evidence of a dose–response effect. Importantly, in both papers, taking into account differences across the depression groups in levels of physical activity, cognitive function, functional impairments and physical illness led to complete attenuation of any relationships. This suggests that these factors either confound or mediate the depression–mortality gradient.

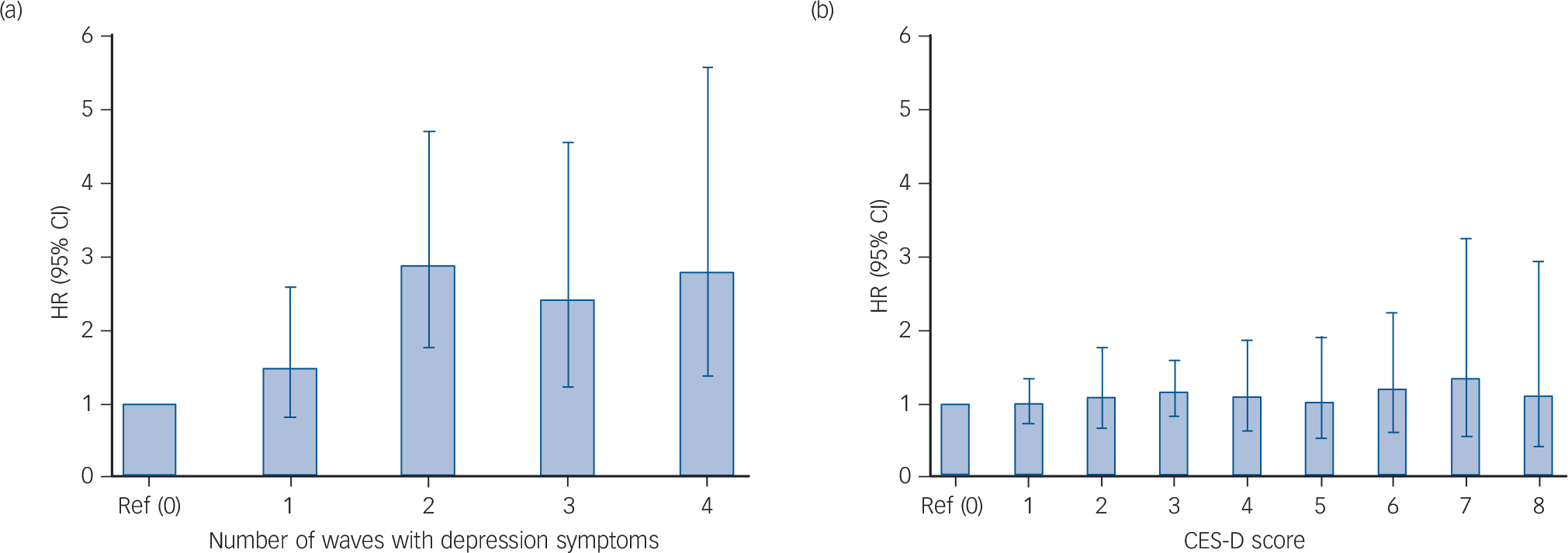

Contrary to Kawada's view, we do not think that studies of sick populations – in the examples given, patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) – offer any insight into the link between depression and the future occurrence of CVD events (aetiology). In our papers, concerns regarding a lack of statistical power (for analyses of depression duration) and space constraints (for analyses of depression severity) prevented us from reporting relationships with cause-specific mortality, including CVD. We take this opportunity to do so here. Figure 1 shows the analysis requested by Kawada. We see associations of the duration of depression symptoms (Fig. 1a: 233 CVD deaths in 9560 people over a median of 3.6 years of follow-up adjusted for age and gender) and the severity of symptoms (Fig. 1b: 703 CVD deaths in 11 104 people over a median of 9.7 years of follow-up adjusted for age, gender and ethnicity) with CVD mortality. These figures show a somewhat similar shape to that apparent for all-cause mortality for the association with duration of depressive symptoms and a flatter association for symptom severity. In both analyses the wide confidence intervals illustrate the low precision of the point estimates.

Fig. 1 Hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for the associations of duration (a) and severity of depressive symptoms (b) with cardiovascular disease mortality in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. HRs adjusted for age and gender (a); age, gender and ethnicity (b).

In conclusion, our results seem to accord with extant literature that has found basic adjustments reveal effects are lost after taking into account multiple covariates. Advancing this field now requires a more rigorous examination of cause and effect. Among other approaches, this could be tested using aetiological trials in which the impact of successful treatment for depression on CVD risk is quantified, or using Mendelian randomisation where gene variants for depression are employed as instrumental variables to explore apparently unconfounded associations with CVD.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.