On December 20, 1661, indigenous members of the Zapotec Cofradía of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception gathered in their chapel in the Barrio San Diego of Ciudad Real (today San Cristóbal), Chiapas. By the mid seventeenth century, cofradías such as this one were ubiquitous across Chiapas and broader Spanish America and played a central role in religious life. These self-governing mixed-sex lay religious brotherhoods organized collective devotion to particular saints and provided members with mutual aid in sickness and in death. In Chiapas and other parts of Central America, they often helped fund basic liturgical costs as well.

Each year in December, members of the Cofradía of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception met to elect their officers, and that year they elected six men and six women. The male officials were listed first, in ranked order: one prioste (steward), one alcalde (mayor), one mayordomo (administrator) and his two assistants, and one unnamed male position assigned to an adjacent native (Mixtec) neighborhood of San Antonio. The records then listed the female officials, also in ranked order, beginning with the priora (prioress) “of the city” and her assistant. Four more female prioras were evenly divided, with two assigned to their own neighborhood of San Diego and two assigned to the Mixtec barrio of San Antonio.Footnote 1

From the surviving records it is unclear when the cofradía began electing women alongside men. But the manner in which the election was recorded in 1661, with no fanfare or explanation for the election of equal numbers of male and female officials, suggests the practice had been ongoing for at least some time. The record book ends in 1675 and subsequent books appear to be missing or destroyed. But a fragmentary record from 1777 indicates that elections of both men and women continued into the late colonial period, with few modifications.Footnote 2

The 1661 election of six female officials in the native cofradía of Ciudad Real appears as the earliest recorded case of formalized female cofradía leadership in Chiapas, but it certainly was not the last.Footnote 3 An analysis of surviving cofradía books from colonial Chiapas, approximately 200 in all, reveals that close to 50 cofradías elected female officials. Some embraced the practice intermittently, but well over half consistently elected women for decades or more, through the late colonial period and in many cases well into the nineteenth century. These cofradías were spread over 20 towns from diverse topographical and ethnolinguistic regions of Chiapas (see Figure 1). Indigenous cofradías were clearly at the forefront of this practice; however, election of female cofradía officers also became remarkably popular among ladino, Black, and even Spanish cofradías during the eighteenth century.

Figure 1 Mexico, State of Chiapas

Map created by Man Qi (2021) based on map by Edith Ortiz Díaz. Source: Edith Ortiz Díaz, “El Camino Real de Chiapas: eje del Desarrollo económico y social de los siglos XVI y XVII,” in Los pueblos indígenas de Chiapas: atlas etnográfico, ed. Margarita Nolasco Armas (México, D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2007).

These findings challenge the common generalization that in colonial New Spain “cofradía officers were men.”Footnote 4 Or, as another scholar puts it more broadly, “Spanish custom and Christian doctrine excluded women from positions of authority.”Footnote 5 This perception reflects the scholarly tendency to focus on central Mexican regions where Spanish colonialism more effectively constrained women's participation in formalized leadership roles. There scholars have found only a select few native cofradías that formally elected female officers, mostly in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. Afro-Mexican cofradías picked up the practice in the seventeenth century, but over the eighteenth century both native and Afro-Mexican women largely retreat from view in the official cofradía records from central Mexico.Footnote 6 Meanwhile, Spanish cofradías in that region rejected the practice, apparently due to its close association with native and African communities.

By shifting focus beyond central Mexico, this article illustrates the diversity and dynamism of colonial gender relations and native women's roles and experiences. Scholars agree that Spanish colonialism undermined native women's status alongside that of the broader native population, and also in specifically gendered ways. While early modern Spanish and European societies viewed men as intellectually, physically, and morally superior to women, pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican societies combined female subordination with systems of gender complementarity and parallelism. Many creator deities were dual-gendered, or male and female deities acted together, as both male and female natures were necessary for creation. That cosmological complementarity was reflected in diverse ways across Mesoamerican societies—in kinship relations, labor systems, and religious, economic, and political institutions.

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican women had access to property and inheritance rights and in central Mexico parallel leadership positions frequently existed in neighborhoods, palaces, temples, markets, and schools.Footnote 7 Some scholars go as far as to argue that Spanish colonialism fully dismantled gender parallelism and stripped native women of all traditional rights and privileges.Footnote 8 Susan Kellogg and others find less of an abrupt rupture and more of a steady yet “marked decline in status” for seventeenth-century native women in central Mexico, as gender complementarity and parallelism gave way to a “separate and unequal” model of gender relations.Footnote 9 Native women's relative power loss was more acute, given that noble, and eventually non-noble, native men found ample opportunities for formal political and religious leadership positions within Spanish colonialism as town council members, mayors, governors, Christian school masters, and lay leaders.

While native women undeniably lost power and privileges under Spanish colonialism, recent studies also show that many native women continued to claim informal political, economic, and religious authority within their communities.Footnote 10 Chiapas's cofradía records demonstrate that native women also systematically claimed formal elected positions of religious leadership in some regions of New Spain. Not just symbolic, these offices included significant responsibilities, such as management of finances, collecting alms, modeling Christian piety, coordinating devotions, tending to images and altars, and caring for the spiritual and physical well-being of fellow members. Formal cofradía offices allowed native women critical access to prestige, status, and authority within their communities. This was increasingly true over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as native hierarchies shifted and officeholding (on town councils and cofradías) replaced noble lineage as the primary marker of elite status and role in local governance. Based on the generalization that women were barred from secular and religious officeholding, Catherine Komisaruk argues that this shifting of hierarchies marginalized noble native women across Central America.Footnote 11 But evidence from Chiapas reframes that perception. Through cofradía officeholding, native women in different parts of Chiapas established themselves as community leaders whose labors often overlapped with the work of town councils to ensure community well-being and survival. Rather than retreat over time, the practice of electing female cofradía officials appears to have expanded in late colonial Chiapas, both geographically and demographically, to the point that even elite Spanish cofradías were electing women by the late eighteenth century.

Cofradía records indicate that migration, movement, cross-cultural exchanges, and distinctive regional contexts led to dynamic adaptations in local gender norms and practices, as well as in Church policy. Chiapas's distinctive spiritual economy, for example, apparently led Spanish missionaries and bishops to prioritize the pragmatic value of female leadership over the enforcement of strict Spanish gender norms. This article also considers how Nahua and Oaxacan indigenous conquerors and colonizers of Chiapas played a critical role in the establishment and endurance of formalized female leadership in cofradías, as did local native creativity and adaptation in the face of extreme economic exploitation and hardship. Scholars are only just beginning to examine the rich history of indigenous colonizers in Central America, and little is known about native female colonizers.Footnote 12 This article sheds new light on the ways in which gender shaped native identity and community formation during the colonial period as indigenous conquerors and colonizers of Chiapas, as well as “reduced” and resettled Maya populations, invoked the cosmological links between motherhood, gender complementarity, and place-making in their formal elections of female cofradía officers.

Tracing the Early Origins of Female Cofradía Leadership

Through the colonial era, Chiapas was part of the Kingdom of Guatemala, an administrative jurisdiction within broader New Spain that included the modern-day Central American nations of Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. Colonial Central America was mostly a modest province in terms of both mineral assets and native populations next to the riches of central Mexico. At the onset of the conquest era, scholars estimate that Chiapas had approximately 350,000 native people, but that number declined precipitously due to disease and over-exploitation, stabilizing at between 50,000 and 75,000 during the eighteenth century.Footnote 13

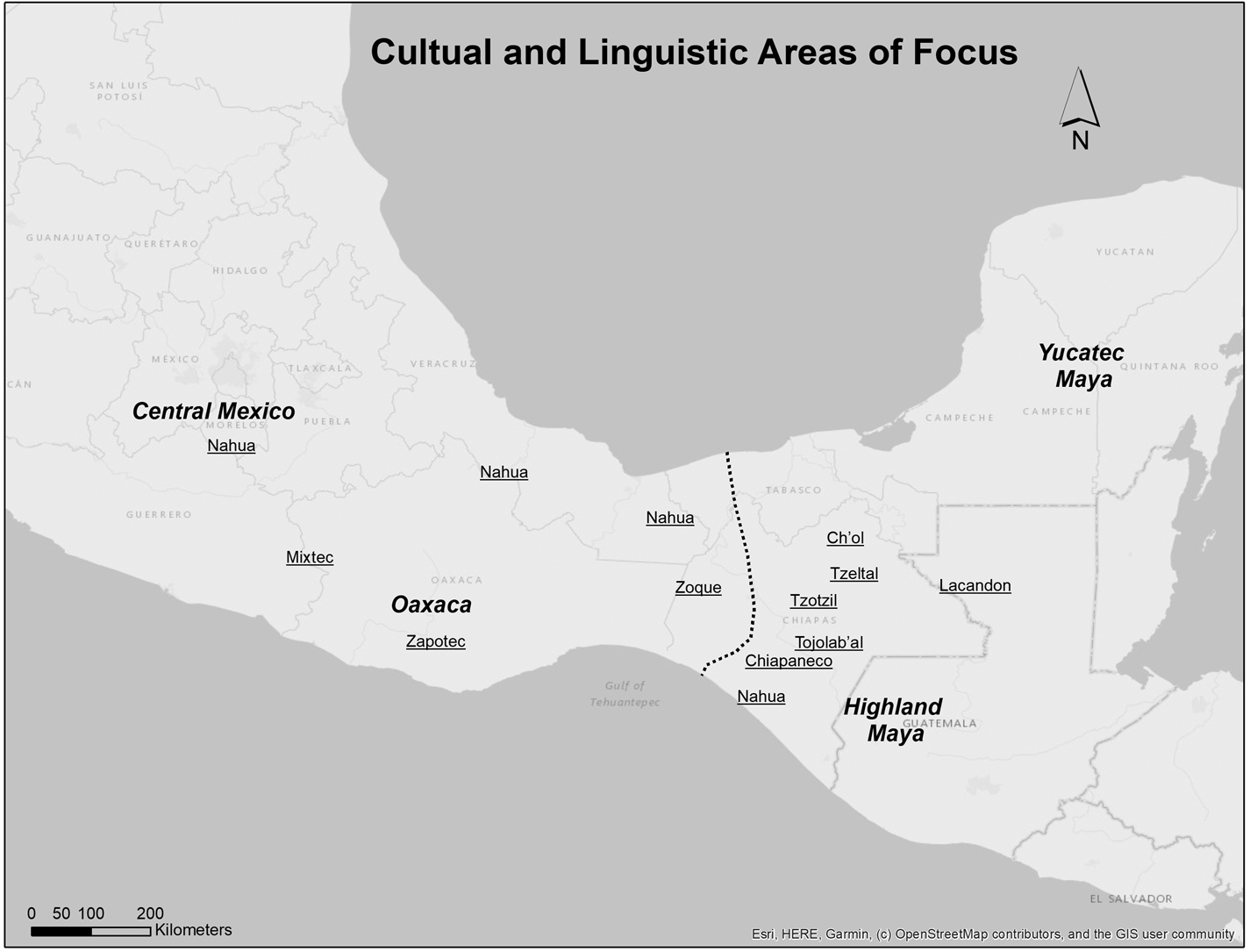

Chiapas's native population may have been relatively small, but it was remarkably diverse. Maya dominated the cool highlands and eastern rainforests. Among the Maya were several distinct ethnolinguistic groups, including the Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Ch'ol, Tojolabal, and Lacandon. In the western lowlands were non-Maya societies such as the Zoque and Chiapaneca. As the opening case study highlights, enclaves of Zapotecs and Mixtecs from Oaxaca and Nahuas from central Mexico could also be found, a legacy of their prominent role in the conquest and colonization of Central America (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Cultural and Linguistic Areas: Central and Southern Mexico to the Yucatan and the Guatemalan Highlands

Map created by Man Qi (2021) based on map by Laura Matthew. Laura Matthew, Memories of Conquest: Becoming Mexicano in Colonial Guatemala (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

Chiapas's small native population and modest economic opportunities attracted very few Spaniards, and through the late colonial period they consistently represented just 2 percent of the total population, mostly clustered in Ciudad Real and a few select towns. Spanish demand for enslaved African labor in urban households and on cattle ranches and sugar plantations led to the steady if modest growth of a Black and mulatto population, particularly in Ciudad Real. By the late colonial period, Black and mulatto residents accounted for 4 percent of the total population, significantly outnumbering Spaniards.Footnote 14 Ladinos, a catchall term common throughout Central America for Hispanicized natives and people of mixed indigenous and/or African heritage, represented another 6 percent of the total population.Footnote 15

Evangelization efforts began in earnest in the 1540s when the famed Bishop Bartolomé de las Casas arrived with almost two dozen Dominican missionaries, establishing a long-lasting precedent of Dominican control over most of Chiapas.Footnote 16 Dominican missionaries founded the earliest cofradías in Chiapas in the 1560s in highland Mayan Tzeltal and Tzotzil communities. Franciscans, Mercedarians, and secular priests soon joined those efforts and cofradía foundations expanded rapidly alongside missionary campaigns through the region in the early seventeenth century. By 1625 there were approximately 200 official cofradías in the bishopric of Chiapas.Footnote 17 For missionaries and bishops, native cofradías served as a key source of revenue in a region with few economic resources. While native communities resented and resisted Church extractions of wealth through cofradías, they also found the institution to be a useful mechanism for semiautonomous coordination of public ritual life and reinforcement of community bonds.Footnote 18 Over the course of the seventeenth century, native enthusiasm for cofradías grew, and some communities began pressing for cofradía foundations of their own accord. A civil official in 1691 found 282 cofradías in 84 towns, and that number continued to grow over the eighteenth century.Footnote 19

The earliest record of female officeholding in Chiapas comes from 1661 in a Zapotec cofradía in Ciudad Real, the bishopric seat for the region. The lack of surviving cofradía records before the late seventeenth century makes it difficult to determine the precise origins and development of this practice in Chiapas and in broader Mesoamerica, but there are traces in the records that provide some clues. Female officeholding was almost nonexistent in medieval Spain, but appeared right from the start in colonial New Spain with the 1552 foundation of one of the very first indigenous cofradías in the New World, the Cofradía of San Josef de los Naturales in Mexico City.Footnote 20 The cofradía's constitution, written in Nahuatl, listed four male deputies and four female officials with the title cihuatepixque (woman in charge of people, or ward elder).Footnote 21

The number four was central to Mesoamerican cosmology and spatial-political organization, reflecting the four cardinal points for organizing the cosmos, cities, neighborhoods, and houses.Footnote 22 The cofradía borrowed the female officer term from secular municipal government, in which ward elders, male tepixqui and female cihuatepixque served as mid-level officials appointed by colonial cabildos (town councils) to organize and oversee male and female activity respectively.Footnote 23 These lower-level officials are often invisible in colonial documents; however, sixteenth-century Dominican friar Diego Durán offered a rare glimpse of them in Mexico City, noting that “in order to gather the women, there were old Indian women, appointed by all the wards, who were called cihuatepixque, which is to say ‘keeper of women,’ or guardians.”Footnote 24 Although the San Josef constitutions are silent about the role played by female officials, use of the secular cihuatepixque title and the women's positioning alongside four male officials, strongly suggests a continuity of pre-Hispanic Nahua gender systems, in which women and men “played different yet parallel and equally necessary roles.”Footnote 25

Two cases further illuminate important early patterns and trends later seen in Chiapas and Central America. The 1619 rules for the Cofradía of San Miguel Coyotlan, also written in Nahuatl, recalled the 1552 San Josef constitution, noting that alongside the male prioste would be a cihuatepixque or capitana (captain) who would be “in charge of people,” further specifying their duties as taking care of religious objects and serving at funerals, processions, and hospitals.Footnote 26 And in 1604, the Cofradía of the Most Holy Sacrament in the Nahua town of Tula began electing four unnamed female officers during a moment of crisis and mismanagement.Footnote 27 They were simply called “old women,” an ambiguous title that nevertheless recalled Fr. Duran's earlier description of the secular female ward elders. Their roles, as outlined in the election records, also evoked the ward elder model, noting that the women would “keep people in order, so that the holy things (sacraments) will be respected and the offerings will not be (wasted); they too will approve what is used (spent), and they will admonish people and instruct them to be prudent.”Footnote 28 James Lockhart points out that women made up more than half of the cofradía's membership from its inception, and he suspects that these “old women” had occupied informal positions of authority since the beginning.

The women resurfaced again in 1631, at which time the cofradía recorded broader duties and described them using the Nahua term ‘tenantzin,’ meaning mother of the people in holy matters or spiritual mother. The tenantzines’ duties were broadened to include recruiting people to the cofradía, physical and spiritual care for orphans and the sick, and (in an ambiguous but sweeping reference) taking “good care of the holy cofradía so it will be much respected.”Footnote 29 The next year, the four women were described using the Spanish term ‘diputadas’ (deputies), and they were formally listed in the election record, albeit after their male colleagues. The Tula cofradía continued to elect female diputadas through the seventeenth century, even increasing their number from four to six and then to 14 by the 1680s. Unfortunately, subsequent records are far less detailed, making it impossible to determine if female leadership continued.Footnote 30

To date, scholars have found few other records of formal female officeholding in indigenous cofradías in central Mexico. One extensive study of cofradías in a central Mexican native town notes that “women were invisible” in most of the documentary record.Footnote 31 Nicole Von Germeten finds scattered references to mayordomas, madres mayores (senior mothers), and capitanas in native and Afro-Mexican cofradías in three cities in central Mexico, but those positions often appear to have been informal and were certainly disconnected from financial matters. In any case, Von Germeten finds that women's opportunities for leadership posts began a steady decline in the eighteenth century.Footnote 32 One notable exception was the Jesuit-affiliated Nahua Good Death Society in eighteenth-century Mexico City, which alongside male officials, elected upward of 25 women annually to care for the altar and church, recruit members, perform ritual sweeping, report sickness among members, and monitor moral behaviors.Footnote 33 Perhaps more discoveries have yet to be made, but at the current moment it appears that for central Mexico Spanish colonialism largely succeeded in discouraging the formal election of female leaders, particularly by the late colonial period.

By contrast, in colonial Chiapas female officeholding became a consistent and widespread phenomena over the colonial period, continuing past independence. Evidence strongly suggests that the indigenous conquerors and colonizers of Chiapas, Nahuas from central Mexico and Zapotecs and Mixtecs from Oaxaca, played a key role in this process (see Figure 2). As recent studies make clear, the so-called “Spanish conquest” was in many ways an indigenous affair. Tens of thousands of indigenous warriors from central Mexico and Oaxaca, alongside a few hundred Spaniards, conquered and colonized Central America.Footnote 34 Between 1524 and 1542, successive waves of indigenous central Mexican and Oaxacan colonists, including women and children, settled in Central American cities, creating distinct ethnic-enclave communities and claiming privileges as valued “Indian conquerors,” for centuries.Footnote 35

Nahua, Zapotec, and Mixtec women arrived with the very earliest waves of Indian conquerors as well as later colonizers, as they accompanied their husbands and provided critical assistance in transporting supplies and preparing food.Footnote 36 In Chiapas, Ciudad Real's Spanish population apparently recognized the importance of women and families, because in 1529 they requested 200 more Indian settlers “with their women for the pacification of the land.”Footnote 37 Research on central Mexican colonizers in Central America remains in a nascent phase; however, one scholar finds that Nahua norms shaped the formation of municipal councils throughout native towns in Central America.Footnote 38 A parallel dynamic appears to be at work within cofradías as well.

In broader Central America, the earliest known record of female officeholding is from 1632 in a “Mexicano” neighborhood of Nahua and Oaxacan colonists in Guatemala's capital city of Santiago de Guatemala (today Antigua). Closely paralleling the timing and terms of central Mexican cases, the Cofradía of San Joseph elected four tenantzines, or spiritual mothers, “the most devout to be found.”Footnote 39 They were to tend to the cleanliness of the altar and help to collect alms. Later records stipulated that the four women, like the male mayordomos, should care for fellow members who were sick and prepare them for burial in case of death. Additionally, female officials were ambitiously charged with protecting the moral health of the community, making sure “that our fellow members are rid of any sin,” working to prevent “some from speaking ill of others,” and ensuring that “no one is idle or vagrant.”Footnote 40 Although more research is necessary to fully understand this practice in colonial Guatemala, it clearly survived into the eighteenth century. Laura Matthew finds, for example, that eighteenth-century “Mexicano” cofradías in Guatemala's Ciudad Vieja, comprised of the descendants of Nahua and Oaxacan Indian colonists, regularly elected women as capitanas and diputadas.Footnote 41

Movement, Motherhood, and Place-Making

In Chiapas, the earliest records of elected female leadership in cofradías come from Zapotec and Nahua settler communities in Ciudad Real. By 1660, if not before, the aforementioned Zapotec cofradía in Ciudad Real was electing women as prioras of the city and of specific barrios, echoing the earlier ward elder model.Footnote 42 Similarly, the earliest surviving records of the Nahua Cofradía of the Nazarene Christ in Ciudad Real's Mercedarian convent church recorded the election of four female prioras in the late 1670s. Ciudad Real's Zapotec and Nahua colonist communities dated back to the early years of the city's founding. Lacking natural defenses, Ciudad Real's Spanish population relied heavily on Indian allies, who settled in neighborhoods around the city's small Spanish center. Nahua allies settled on the north side of town, while Oaxacan Zapotecs and Mixtecs settled on the south side.Footnote 43 The cofradías’ constitutions have not survived or have yet to be uncovered, so it is unclear when the cofradías were first established and if female positions were institutionalized from the beginning, or if the practice arose over the seventeenth century. Given the election of female leaders in some sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Nahua cofradías in central Mexico, it is entirely possible that women had been serving in a formalized capacity for years, perhaps even several decades.Footnote 44 In contrast to central Mexico, formalized female leadership clearly endured in Chiapas, as the Zapotec and Nahua cofradías in Ciudad Real continued to elect female officers until at least the late eighteenth century and perhaps beyond.

Female officeholding is also particularly evident in southwestern Chiapas, in the Soconusco region, where Nahua colonization began well before the arrival of the Spanish and continued during the Spanish colonial era (see Figure 2). In the town of Escuintla, the Cofradía del Rosario clearly had an established tradition of electing female leaders by the early eighteenth century.Footnote 45 In 1716, the cofradía elected 13 male officials, and eight female officials. Although male positions were described using Spanish terms (mayordomo, diputado, sacristán), female offices were described using a variation on the familiar Nahua term for spiritual mother. They elected two “Tenansi mayores” (older or Senior Mothers) and six “Tenansi menores,” (Younger or Junior Mothers).Footnote 46 A very similar pattern emerged in another Nahua-colonized Soconusco town, Tapachula, where eighteenth-century records for the Cofradía of the Most Holy Sacrament and the Cofradía of Our Lady of Sorrow document the election of women as prioras or capitanas and “Thenantzis.”Footnote 47

Regional distinctions within Mesoamerican gender norms may explain, at least in part, the early and persistent formalization of female cofradía leadership positions within Indian colonist enclave communities. Notions of gender complementarity and parallelism were broadly shared across pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica; however, the more highly bureaucratized Nahua and Oaxacan societies offered native women greater opportunities for institutionalized leadership than did the Maya.Footnote 48 For example, Nahua women occupied several public positions parallel to those of men, as neighborhood officials; priestesses; and administrators of markets, temple song houses, and schools of dance.Footnote 49 In Oaxaca, Mixtecan codices highlighted both priests and priestesses as central to religious life and depicted political units through glyphs of a “ruling couple” seated on a mat and facing one another.Footnote 50 Until at least the seventeenth century, Mixteca women continued to inherit the title of cacica (noblewoman) within their communities, along with the wealth, status, and authority this position entailed.Footnote 51

Although the Zoque societies of western Chiapas are woefully understudied, they likely shared more in this regard with their Oaxacan neighbors than with highland Maya. After the Zapotec and Nahua cofradías of Ciudad Real, the next earliest records of native female officeholding in Chiapas come from 1685 and 1690, in the Zoque town of Ocozocoautla.Footnote 52 Around the same time, in the neighboring Zoque town of Jiquipulas, Church officials discovered a heterodox cofradía in which male-female couples operated as mayordomos to organize devotion to a female goddess named Jantepusi Ilama in a local cave.Footnote 53 Over 50 years later, the ladino Cofradía del Rosario in another Zoque town, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, echoed this format, electing male-female pairs, first husbands and wives and then mothers and sons as the principal priostes.Footnote 54 And modern-day ethnographers note that Ocozocoautla's neighborhoods continue to elect husband-wife pairs, as well as subordinate male and female officials, to organize ritual devotion to local saints through a cofradía-like institution known as the cowiná.Footnote 55

Diverse Mesoamerican gender norms are clearly part of this story, but they do not explain why Nahua and Oaxacan migrant/colonist communities in Central America appear to have been more apt to formalize female leadership positions than those that remained in central Mexico. Indian colonizers' carefully-nurtured identity as foreigners in Chiapas, alongside the persistent use of the Nahua term ‘tenantizn,’ or its Spanish translation ‘madre,’ suggestively hints at the ways in which gender fundamentally framed the experience of Central America's Indian colonizers. In Mesoamerican mytho-histories, towns and lineages were born from ancestral couples, original mothers and fathers, much as all of creation emerged from dual-gendered deities.Footnote 56

Kathryn Hudson and John Henderson further argue that motherhood in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica “played a key role in place-making and in the legitimation of rulers.”Footnote 57 For example, Nahua histories often marked the founding of new communities with symbols intimately linked to women and motherhood—caves, temescales (steam baths), and houses. Hudson and Henderson conclude that linking newly settled towns to motherhood “would have served to balance perceptions of foreignness” and “could provide the local rootedness essential to legitimate authority.”Footnote 58 During the colonial era, cofradías, militias, and town councils, and the “rituals, gestures, and habits” associated with those institutions, were at the center of Nahua and Oaxacan identity construction in Chiapas and broader Central America. For Indian colonizers whose privileges depended upon remaining forever foreigners, the formal election of female cofradía officers as madres may have supported the ongoing ritual establishment of a new home in a new land while at the same time rooting them in their new home in a way that balanced their identity as settlers.

Mapping the election of female cofradía officials provides another context for understanding the reach of the practice across colonial Chiapas. The election of female cofradía officers occurred prominently along major routes of travel and commerce (see Figure 1). Economic growth in the late seventeenth century fueled indigenous mobility and regional networks along major roads, as well as informal highland routes.Footnote 59 In fact, one historian describes Chiapas's indigenous population as “constant travelers.”Footnote 60 For example, the haciendas around Ocosingo began drawing migrant laborers from afar, and those interactions were reinforced through trade and religious festivals. The aforementioned seventeenth-century Zoque devotion to the female goddess Jantepusi Ilama in a cave near Jiquipilas drew pilgrims from highland Tzeltal and Tzotzil Mayan towns.Footnote 61 At the same time, the rising popularity of the Black Christ of Tila also drew pilgrims from Tzetlal, Tzotzil, and Zoque regions.Footnote 62 Native lay Church leaders such as sacristanes (sacristans) and maestros de coro (choirmasters) developed particularly close relationships with their counterparts in other towns, relationships that were often reinforced through ritual kinship ties.Footnote 63 Given the location of cofradías that elected female officers, it appears that these regional economic and religious networks facilitated the spread, or at the very least reinforced the persistence of this practice.

But there were also local factors that may well have spurred the embrace of formal female leadership in the Maya highlands. Nahua and Oaxacan colonizers were not the only native peoples experiencing relocation, migration, and the founding of new homes in colonial Chiapas. Nor were they the only Mesoamericans who conceptually linked motherhood, home, gender complementarity, and good governance. Many Maya languages, including Tzeltal, use nearly identical words for “house” and “mother,” and to this day the Maya describe local founding ancestors and ritual specialists as “mothers/fathers.”Footnote 64 Male/female complementarity is particularly essential for acts of creation and reproduction, such as maize production and establishing new communities.Footnote 65 The existence of female cofradía officers, often described as madres, in several resettled and relocated Maya (Tzeltal, Tzotzil, and Ch'ol) communities suggests the possibility of a broader gendered process of place-making beyond that accomplished by central Mexican Indian colonists. As early as 1549, recently freed Tzotzil, Tzeltal, and Zoque slaves settled together in the Cerrillo neighborhood of Ciudad Real.Footnote 66 During the 1560s, Dominican missionaries founded new towns, including Comitán, Yajalón, Bachajón, and Tila, among others, in which they “reduced” native populations, mostly Maya Ch'ol or Tzeltal. In the case of Comitán, Dominicans merged four ethnic linguistic groups: Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Ch'ol, and Caxhog.Footnote 67 Missionaries also resettled Ch'ol Maya and other native populations from the Lacandon jungle to existing towns, such as the Tzeltal town of Ocosingo.Footnote 68 This same region experienced another round of massive unrest, movement, flight, and resettlement after the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712.

Newly founded or recongregated towns became principal sites of formalized female cofradía leadership in the Mayan highlands. By the early eighteenth century, an established practice of electing female cofradía officers existed in Comitán, Ocosingo, and Yajalón, and an informal practice of madres working alongside male officials existed in Tila. For Bachajón and Ciudad Real's Cerrillo neighborhood, the earliest surviving cofradía records date from the late eighteenth century; at that time each community had a cofradía electing female officers, although it is impossible to determine when that practice began. With the exception of Bachajón, cofradías in these newly founded or recongregated communities used the term ‘madre’ to describe female officers, as well as the term ‘priora.’ Like central Mexican colonizers, these resettled Maya populations were also creating new homes in new places and building or rebuilding a sense of collective identity.

Chiapas's Native Cofradía Economy and Women's Financial Networks

Chiapas's distinctive spiritual economy and the severe economic strains and exploitation experienced by the region's native cofradías provide another critical context for the spread and persistence of formalized female leadership within them. Due to the lack of Spanish, free Black, and mestizo settlers in the region, the Catholic Church in Chiapas collected the lowest tithes in all of New Spain and faced chronic funding shortages.Footnote 69 In response, Chiapas's missionaries and local priests relied heavily on native communities and their cofradías to help sustain basic church functions. The Church's exploitation of native cofradía funds dramatically intensified in the early eighteenth century, when Bishop Juan Bautista Álvarez de Toledo began extracting excessive fees during pastoral visits in order to fund ambitious projects in Ciudad Real. While the previous bishop had charged native towns eight pesos per pastoral visit every three or four years, Bishop Álvarez de Toledo required eight pesos from every native cofradía within each native town and began conducting visits more frequently. His successor followed suit and further demanded that native cofradías provide eight pesos every year.Footnote 70 Even among Church officials accustomed to colonial exploitation of native wealth, the moves were seen as grossly abusive. In his lengthy chronicle of the region's history, Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez explicitly held Chiapas's bishops and their “reckless greed” responsible for provoking the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712, one of the largest and most radical colonial rebellions before 1750, in which over 30 towns in the Maya highlands attempted to overturn Spanish colonialism.Footnote 71

By the early eighteenth century, cofradía officeholding had become an increasingly challenging and burdensome task in Chiapas's native towns. The protracted economic and demographic crises afflicting highland Maya communities following the defeat and repression of the Tzeltal Rebellion only further amplified the burdens of native cofradía leadership.Footnote 72 Given these circumstances, some communities struggled to find candidates willing to serve as cofradía officials at all.Footnote 73 In this context, female cofradía leadership was sometimes a temporary crisis measure due to a complete lack of male candidates. For example, the Zoque Cofradía of San Antonio Abad in Ocozocoautla elected a woman as the primary mayordoma for two years, from 1752 to 1754, in the absence of any male officials.Footnote 74 Similarly, in Yajalón, the Tzeltal Maya Cofradía del Rosario in 1748 elected only female officers, before returning to its traditional mixed-sex leadership in 1749.Footnote 75

But in many cases, the election of female officials became a permanent practice that apparently helped cofradías to remain financially solvent by tapping into female networks and productive capacities. Cofradía records in colonial Chiapas generally provide scant details about the roles and responsibilities of either male or female leaders; however, it is clear that many female officials were actively involved in cofradía finances, particularly alms collection and management and investment of principal funds.Footnote 76 For example, in 1671, Ciudad Real's Zapotec Cofradía of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception recorded that the priora mayor, Melchora Arias, submitted 24 tostones (50-cent coins), or 12 pesos, while the priora assigned to the neighboring Mixtec barrio of San Antonio submitted 10 tostones, or 5 pesos, “from what was gathered in alms.”Footnote 77 That year and in subsequent years, the currency provided by female leaders amounted to roughly 10 percent of the total cofradía funds.

Other cofradías used euphemistic phrasing that strongly suggested female officials’ involvement in collecting alms. In the 1780s, the indigenous cofradía of Santa Veracruz in Ciudad Real's Barrio Cerrillo elected nine female officials alongside five male officials, describing some of the female officials as “madres de la taza” (mothers of the cup) or “madres del canasto” (mothers of the basket).Footnote 78 A fleeting reference from the Ch'ol Maya town of Tila suggests that women also participated in collecting alms, in an informal capacity. Although Tila's Cofradía de Ánimas never recorded the formal election of women, a 1702 entry noted that it had no principal or funding beyond the “alms that the officials and madres collect in the town, with which they covered expenses.”Footnote 79 Given the size and income of most native towns in Chiapas, it is quite possible that female officials traveled to other towns to collect alms, perhaps in the context of familial or community movement for work, regional religious festivals, or pilgrimages to holy images.Footnote 80

Even without the burdens added by the Catholic Church, most colonial cofradías in Chiapas were poor, lacked properties and endowments, and relied on alms and humble member fees and donations.Footnote 81 In this context, female officials surely provided a pragmatic form of support. Edward Osowski finds for Nahua communities in central Mexico that women's involvement as informal alms collectors often “increased donations” due to donors’ respect for “women's spiritual authority.”Footnote 82 Studies for other regions of colonial New Spain and broader Spanish America also find that women were often the most enthusiastic participants and supporters of cofradías and pious works.Footnote 83 Given norms of gendered interactions, female officials were better positioned than their male counterparts to collect alms from other women.Footnote 84 In more commercialized towns like Ocozocoautla, Escuintla, and Ciudad Real, markets were probably a prime venue for female alms collectors, given women's active participation as both sellers and buyers.Footnote 85

The most innovative aspect of female leadership in Chiapas's cofradías was women's active participation alongside male colleagues in the management and investment of funds, a pattern not seen elsewhere. For example, in 1685 the Zoque cofradía of San Joseph in Ocozocoautla elected one male prioste and his three male assistants alongside one female priora and four madres who were charged with managing 220 tostones (110 pesos), the cofradía's total principal.Footnote 86 Lest there be doubt that female officials received a share, records from 1688 clarified that the cofradía's principal of 200 tostones was “distributed among these subjects, men and women . . . entrusting them to ensure the money increases.”Footnote 87 Similarly, in the 1730s, the cofradía of the Holy Sacrament in the Tzotzil Maya town of San Felipe entrusted two male mayordomos and an assistant, alongside two madres, with the principal each year, apparently counting on them to secure an increase of roughly 5 percent per year, which they did in most years.Footnote 88 And records from the 1780s indicate that the indigenous cofradía of Santa Veracruz in Ciudad Real's Barrio Cerillo divided the principal funds almost evenly between the highest male and female officials, two male mayordomos and the female priora and her assistant. In 1780, for example, mayordomos Juan Hernández and Joseph Hernández each received 14 pesos and 6 reales (one-eighth of a peso), while priora Anizeta Gómez received 13 pesos and 6 reales and her assistant Ignacia Gomez received 12 pesos and 6 reales. Three other male diputados and seven madres apparently were not charged with managing or investing funds, as they received nothing.Footnote 89

How exactly male and female officials managed and invested cofradía funds is not clear. Perhaps they simply lent out the small sums of money at interest. It certainly was not unusual to find native women, as well as women of other ethnic backgrounds, participating in economic networks and operating as moneylenders in towns and cities across Mesoamerica.Footnote 90 Female officials may have also relied on their trade and petty commerce networks. In neighboring Oaxaca, male cofradía officials used cofradía funds for “entrepreneurial engagement,” such as purchasing and transporting sugar to the coast, where they traded for salt and cotton that could then be sold at a profit back home.Footnote 91 It is also possible that Chiapas's cofradía officials invested the principals in some form of production that provided a return. Adriaan Van Oss finds that Mayan cofradías in the colonial Guatemalan highlands often purchased raw cotton with their principals and sold the finished textiles for a profit.Footnote 92

Although left unsaid by Van Oss, these arrangements depended entirely on female labor to transform cotton into cloth. If Chiapas's cofradías had similarly invested in textile production, they might have taken advantage of the labor of female officials, or counted on female officials to coordinate the labor of female cofradía members. Maya descriptions of female officials as “madres” may also suggest a linkage to cloth production, given long-standing beliefs in the region about the intimate relationship between conception, pregnancy, and childbirth and spinning, warping, and weaving.Footnote 93 One record hints at such a dynamic. In the town of Yajalón, the record of the 1725 elections of the all-female Tzeltal Maya Cofradía of Jesús Nazareno notes that the eight prioras “having received 116 tostones [58 pesos] last year along with their jornales (labor itself or payment for labor) and the alms given by the town, they covered the expenses that came up and now they return the entire principal with an increase of four tostones.”Footnote 94 It appears likely that the female officials’ jornales involved textile production, given its close association with female labor.

Of course, involving women did not always solve native cofradías’ economic woes. At times, both male and female leaders lost their shares of the principal. The 1714 elections for Yajalón's mixed Tzeltal Maya and ladino/Spanish Cofradía del Rosario noted that the male mayordomos “did not have the total principal that they had received,” and similarly the elected madres “did not have at that moment the principal with which they had been entrusted, but that they would do everything possible to submit it shortly.”Footnote 95 By the next year's elections, one male mayordomo and one female priora, having lost their shares of principal funds, had fled to Tabasco.Footnote 96

Spiritual Care, Politics, and Female Authority

In contrast to Chiapas's modern civil-religious cargo system, which emerged in the nineteenth century, colonial cofradía offices were not linked to civil positions on native town councils as part of a prestige ladder that all local leaders ascended.Footnote 97 But colonial cofradías were intertwined with town governance in ways that strongly suggest female cofradía leaders exercised broader public authority in local affairs. Cofradía elections, for example, brought together local residents, native nobles, governors, and town council members, and served as community meetings to discuss and make decisions regarding local affairs.Footnote 98 It seems likely that formally elected female cofradía officers played an active role in those community discussions. Recent scholarship for other parts of New Spain finds, for example, that indigenous women, particularly noblewomen but also commoners, were often active participants in community-wide meetings and decision-making.Footnote 99

Like native town councils, cofradías assumed responsibility for ongoing evangelization efforts, educating and modeling proper Catholic behavior for local communities. Evidence suggests that female cofradía officers participated in this mission alongside male officers and town council members. Use of the term ‘priora’ or ‘priosta’ created a notable parallel between senior female officers and the male office of prioste, typically the highest-ranking male position in Chiapas's native cofradías, a position charged with both financial and spiritual care for the community.Footnote 100 The implication would be that prioras also played a role in the spiritual care of the community. As part of this broader duty, Chiapas's cofradías likely expected elected female officials to serve as pious role models for the community. This expectation was clearly laid out in the earliest Nahua cofradías that elected women in central Mexico and Guatemala. A brief reference made by eighteenth-century Franciscan chronicler Francisco Vázquez suggests similar patterns in the Mayan highlands of Guatemala and perhaps Chiapas as well. Vasquez noted that in many Guatemalan highland Maya communities “cofradía officials and texeles, who are the madres,” attended mass every day, each holding a lit candle in their hands until the priest consumed the Eucharist.Footnote 101

Some cofradía records hint at the ongoing existence of a gendered ward or barrio (neighborhood) elder system, echoing the cihuatepixque role found in sixteenth-century central Mexico. In 1661, Ciudad Real's Zapotec Cofradía of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception elected one priora “of the city” and her assistant, and four “prioras del barrio” (neighborhood prioras), two for their local Zapotec Barrio de San Diego and two for the adjacent Mixtec Barrio de San Antonio.Footnote 102 Over a hundred years later, the cofradía continued to elect and distribute six female prioras by barrio in this same way.Footnote 103 A similar dynamic is apparent in some highland Maya communities where there was a long pre-Hispanic history of towns and cities comprised of multiple calpules (semiautonomous wards) made up of kin-based groups, often with their own local temple and communal lands.Footnote 104 Some cofradías operated entirely within single calpules, but others worked across barrio boundaries and assigned female officials accordingly. Ocosingo, for example, had three calpules assigned to three barrios during the colonial period, and the town's mixed Tzeltal/Spanish Cofradía del Rosario elected one Spanish priosta, presumably for the entire town, and six Tzeltal female officials (alternately described as prioras and madres), two for each of the town's three calpules.

Exactly what duties female officials fulfilled in specific barrios or calpules is difficult to discern. Neighborhood-based alms-collecting was likely a key component, but the broader record suggests other key functions. Female ward elders in the earliest cofradía records from central Mexico and Guatemala also tended to the sick, prepared the dead for burial, attended funerals, and monitored moral behavior.Footnote 105 One early nineteenth-century cofradía record suggests similar female ward duties may have been a common feature in Chiapas as well. In 1810, Ciudad Real's Cofradía de San Francisco, located in the Franciscan church in the historically Zapotec neighborhood of San Diego recorded the election of numerous male and female officials, including a husband and wife as the principal mayordomos and several parallel categories of male and female officials such as “mandatarios/as” (leaders/representatives) and “enfermeros/as” (nurses). The cofradía elected three male mandatorios for the city as a whole, as well as ten female mandatarias who were divided into five teams of two women each, one team assigned to the city and the remaining four teams assigned to four different barrios. Similarly, the cofradía elected two male enfermeros and three female enfermeras for the entire city, as well as 12 more female enfermeras divided equally among the four barrios.Footnote 106 The larger number of female barrio officials relative to their male counterparts may reflect women's gendered identification with specific duties such as caring for the sick, preparing bodies for burial, and “gossip,” that is information exchanges regarding local moral transgressions. Recalling the Mesoamerican significance of the number four and the gendered importance of ritual sweeping, the cofradía also elected 12 groups of four women to sweep the temple for one designated month of the year.Footnote 107 Other records similarly highlight female cofradía officials’ role in the charitable activities of caring for the poor and the sick. In the Tzeltal town of Teopisca, the 1678 constitutions for the Cofradía de Santa Rosa described a gendered division of labor explicitly linked to the model of recently canonized Saint Rose of Lima, America's first saint. The constitutions called for four official female positions dedicated to the charitable spiritual and physical care of the poor and sick. Inspired by Saint Rose of Lima's charity toward the sick and the poor, the cofradía indicated that it would name “dos mujeres principales y charitativas” (two elite and charitable indigenous women) with the title of priora and another two honest widows as their assistants, so that when they hear that there is a sick person, especially ones who have been given communion, they will help them in whatever way they can, such as feeding them, because we know that many die due to lack of help.”Footnote 108 The description of the women as “principales” is noteworthy, given that this prestigious status is typically associated with indigenous men who gained the title through officeholding.

This type of female charitable activity was in line with the female roles outlined by other Mesoamerican cofradías, such as the early Nahua cofradías in central Mexico and Guatemala's capital. However, it is unclear if the cofradía in Teopisca actually followed through with this vision since subsequent records make no mention of female officials in the elections. The omission suggests the possibility that these types of charitable roles were held informally and will remain elusive in the documentary record.

Catholic Officials and Female Authority

Chiapas's Catholic officials clearly accepted formalized female leadership in native cofradías. There is no record of controversy over the matter, no restrictions against women collecting alms, and Dominicans, Franciscans, secular priests, and bishops regularly signed off on elections that included female officials and explicitly referenced women collecting alms and managing principal funds. The Catholic Church's position in Chiapas notably contrasted with official stances in central Mexico, where bishops went so far as to outlaw the collecting of alms by women beginning in the late seventeenth century, “considering it a cause of ‘great inconveniences.’”Footnote 109

Over the eighteenth century, opposition to women collecting alms, particularly native women, only grew, increasing among central Mexican prelates as well as secular colonial officials. Late-colonial reformers in both Church and state viewed native women traveling from town to town to collect alms as “indecent,” a sign of social and gendered disorder that might increase the risk of native migration and escape from tribute requirements. As Nahua cofradías ignored the laws and continued to rely on women as informal alms collectors, secular and Church officials imposed investigations, fines, jail, and seizures of cofradía religious images.Footnote 110 More broadly, central Mexican reformers attempted to undermine and constrain native women's actions, which they deemed “too public and powerful, too masculine” as part of “a larger movement toward a strongly articulated patriarchy.”Footnote 111 Their efforts bore fruit, as opportunities for women of all racial backgrounds to exercise leadership in cofradías declined across central Mexico over the eighteenth century.Footnote 112

In Chiapas, by contrast, alms-collecting by native women and their exercise of public authority through cofradías remained notably uncontroversial through independence. In fact, the late colonial period appears to be a high point of female cofradía leadership in Chiapas, as the practice becomes increasingly evident in more towns and among ladino, Black, and Spanish communities as well. The Catholic Church's acceptance of female cofradía officials through the late colonial period is particularly striking given the region's history of native women's participation and leadership in heterodox religious movements that appropriated aspects of the Catholic cofradía system. In 1585, Bishop Pedro de Feria discovered an unorthodox cofradía near the town of Chiapa de Indios, in which 12 native male “apostles” and two women, titled Santa María and Magdalena, gathered at night in a local cave to conduct ceremonies, convert into gods and goddesses, and thereby ensure the welfare of the community.Footnote 113 As noted above, in the late seventeenth century, Church officials discovered another heterodox cofradía operating in a cave outside the Zoque town of Jiquipilas, dedicated to devotion of the female goddess Jantepusi Ilama and led by paired male-female mayordomos and mayordomas.Footnote 114 And in 1712, the aforementioned Tzeltal Rebellion swept through the Maya highlands under the religious leadership of a teenage girl who communicated directly with an apparition of the Virgin, and whom followers described, using cofradía terminology, as the “mayordoma mayor” (senior mayordoma) of the regional devotion to the Virgin of Cancuc.Footnote 115

Rather than see these incidences as cause to restrict native female authority and public positions, Chiapas's priests and bishops apparently looked to pious native women as useful allies. This strategy was starkly apparent in 1713, in the immediate aftermath of the 1712 Tzeltal rebellion, when Dominican priests and the bishop supported the foundation of a new all-female native sisterhood, the Cofradía of the Nazarene Christ in the Tzeltal town of Yajalón, a prominent participant in the rebellion. That same year, Church officials also endorsed the ongoing female leadership in Yajalón's Cofradía del Rosario.Footnote 116 In subsequent decades, priests and bishops continually signed off on elections of female officers in other towns involved in the rebellion, namely Huitiupán, Chilón, and Bachajón.Footnote 117 This approach fit within a broader missionary pattern across Central America. As I've argued elsewhere, Central American priests and bishops demonstrated greater official tolerance for active lay female religiosity and actively relied upon poor indigenous, Black, and mixed-race women as allies and lay evangelizers.Footnote 118

Economic factors also surely led Chiapas's priests and bishops to tolerate, and maybe even promote, the practice of formalized female leadership. Throughout Central America, Church officials’ heavy economic dependence on cofradías prompted pragmatic adjustments. Archbishop Pedro Cortés y Larraz (1767-79) admitted, for example, that he was unable to curtail cofradías’ autonomy and exuberant practices because Guatemalan churches relied on cofradías to fund basic liturgical necessities and building maintenance.Footnote 119 Within this context, Chiapas's priests likely prioritized female contributions to the survival and financial solvency of Chiapas's cofradías over concerns about proper gender roles and norms.

Ladina, Black, and Spanish Women in Cofradía Leadership

In central Mexico, increasing Hispanicization among native and African communities led to a rejection of formalized female leadership, particularly by the late eighteenth century. In Chiapas, a reverse phenomenon occurred. Not only did native communities continue to formally elect female cofradía leaders, but ladino, Spanish, and Black cofradías emulated the practice through the late colonial period and beyond independence in some cases. Over the course of the eighteenth century, Chiapas's ladino population expanded as more native peoples became Hispanicized in language, dress, and culture, and as the mestizo population grew modestly. For example, by 1713 the Cofradía of the Rosary in the Tzeltal town of Yajalón had a clearly established tradition of electing eight madres alongside male mayordomos.Footnote 120 In the early 1730s, elections began to reflect the growing number of Spanish/ladino members. In 1735, for example, the cofradía elected both native and Spanish or ladino men and women to office.

In 1737, the Spanish/ladino population created their own separate cofradía. Those records are lost, but it seems possible that Spanish/ladina women continued to serve in elected office as they had in the mixed cofradía. At least that is what occurred in the neighboring town of Ocosingo. There, Spaniards and ladinos founded a Cofradía of the Rosary in 1707, explicitly inspired by the town's long-standing native cofradía of the same advocation. The Spanish/ladino cofradía also built directly upon the native practice of female officeholding. Not only did they elect one Spanish priosta, but they also recorded the election of six “prioras Indias” (indigenous prioras).Footnote 121 One historian argues that Ocosingo's native Cofradía of the Rosary actually elected the native prioras; however, they worked with their closely related Spanish/ladino counterparts.Footnote 122 In the 1730s, the ladino population separated completely into its own cofradía, and records confirm they continued electing women as leaders through the 1850s.Footnote 123

Other striking examples come from Tuxtla Gutiérrez, where ladino cofradías frequently elected women to primary positions of leadership. For example, Tuxtla's Cofradía of the Rosary, which explicitly identified itself as “de ladinos,” elected a husband-and-wife pair as the primary priostes in 1747. In the 1750s the ladino cofradía began electing a mother-son pair in which the mother was clearly the senior leader. Male leaders followed during the 1760s and 1770s, but in 1789 the cofradía elected a mayordoma as the primary head and continued to do so until 1813. Similarly, Tuxtla's ladino Cofradia de Ánimas intermittently elected a woman as the primary mayordoma. The earliest surviving records for the cofradía show such an election in 1786, and again in 1794, 1803, 1805 to 1811, and 1826. It is unclear if another Tuxtla cofradía (San José) was ladino, indigenous, or mixed, but it too elected women as the primary mayordomas nine times between 1787 and 1813 and continued to do so intermittently through the 1850s. As this latter case illustrates, it is not always possible to determine if late colonial cofradías were indigenous, ladino, or mixed. Records do confirm, however, that by the late eighteenth century elected female cofradía leaders were found in several towns with high ladino populations, including Comitán, Teopisca, San Bartolomé, Socoltenango, and Tecpatán.Footnote 124

Enslaved Africans brought their own traditions of female religious authority to Catholic cofradías in Spain and the colonial Americas.Footnote 125 It is unclear when Ciudad Real's Black community began electing female cofradía officials, but the practice was clearly well established and ongoing during the late colonial period. By the 1770s, Ciudad Real's Black and mulatto residents, many of them free and well-paid skilled workers, accounted for 15 to 20 percent of the city's population, outnumbering Spaniards. For centuries, Ciudad Real's Black community centered around the increasingly sumptuous San Nicolás Church, known originally as “the little chapel of Saint Nicholas of the Black residents.”Footnote 126 The only surviving record book of the Black Cofradía of San Nicolás begins in the late 1790s and notably documents the 1798 election of a woman, Doña María Dominga Fernandes, as the cofradía's principal mayordoma.Footnote 127 The cofradía elected a man, Don Juan José Pineda, as her assistant, followed in authority by other male mayordomos. The 1798 election of a woman to the primary position of leadership strongly suggests that the cofradía had a longer history of electing female officials, while the use of the honorifics Doña and Don strikingly underscores the level of social mobility and prestige achieved by at least some members of Ciudad Real's Black community. In contrast to central Mexico, Black social mobility in Ciudad Real apparently did not require sidelining women from formalized positions of leadership. Through the mid 1820s, the Black Cofradía of San Nicolás continued electing women as mayordomas, entrusting them with funds and responsibility for particular ritual celebrations such as the procession on Holy Monday or the feast day of Black Saint San Benito de Palermo. In 1820, for example, the cofradía elected Señora Doña Damasa Macal as mayordoma of Santa Gertrudis and provided her with the sizeable fund of 550 pesos. The cofradía also consistently elected four prioras, each dedicated to a particular saint or devotion.

Most surprising is evidence that elite Spaniards in Ciudad Real also adopted the practice of electing women as cofradía officials. By the 1730s, if not before, the Spanish Cofradía de Ánimas in Ciudad Real was electing five female officials annually. Like its native counterparts, the Spanish cofradía elected women as prioras mayores as well as prioras of the cup dedicated to alms collection, a practice that continued through 1810. Similarly, in 1775 Ciudad Real's Spanish Archicofradía of the Holy Sacrament recorded the election of two prioras mayores and two prioras of the cup. The Archicofradía continued electing women in these roles annually, through at least 1839. The Spanish adoption of female officeholding in cofradías in Chiapas noticeably contrasts with trends in central Mexico. In fact, Nicole Von Germeten finds that female cofradía leadership was so thoroughly associated with native and African communities that mulatto men in eighteenth-century central Mexico decisively excluded mulatta women from elected office in an effort to emulate Spanish gender norms and thereby secure social mobility.Footnote 128 It appears that a reverse dynamic was at play in Chiapas, with its small Spanish population and more flexible gender norms. In this context, Spanish as well as ladino and Black cofradías adopted and continued indigenous models of formal female cofradía leadership.

Conclusion

In the decades after independence, the colonial cofradía system continued a process of dynamic adaptation. By the late nineteenth century, the modern native civil-religious cargo system had emerged: cofradía officers individually shouldered financial responsibility for ritual life and men rose to local prominence through an alternating and ascending ladder of civil and religious posts.Footnote 129 Modern anthropologists, as well as historians, long assumed that women were fully excluded from the cargo system and that this exclusion reflected colonial traditions. The evidence presented here clearly indicates that women's absence from formal cofradía offices in the cargo system is a modern innovation, not a colonial legacy, at least in Chiapas. Although more research is required to understand how this transition occurred in the nineteenth century, one possibility is that the creation of an ascending ladder linking religious and civil posts marginalized women due to their long historical exclusion from civil officeholding. Policies after the Mexican Revolution requiring officials to be literate and Spanish- speaking further solidified masculine control of formal officeholding.Footnote 130

But some scholars also call into question early anthropological assumptions about women's total exclusion from the cargo system. For example, Rosemary Joyce points out that Frank Cancian's 1965 analysis of the religious cargo system in Zinacantán ignored women's participation entirely, and yet—buried in an appendix—he noted that “all the auxiliary personnel who came to help the Senior Mayordomo Rey for 1960 brought along their wives and young children. The Mayordomo Rey said that it would be most correct to say that the family, not just the man, is recruited for help, for the women help with the kitchen work.”Footnote 131 More recent anthropologists and ethnographers who have interviewed women find that they describe themselves as cargo-holders alongside their husbands. In that role, they weave and wear special garments, recruit assistants and coordinate labor, provide critical funding, and participate in ritual performances. Communities recognize these women with special titles such as “Mother” or “Lady Steward” and bow before both husband and wife cargo-holders.Footnote 132 More research is required to understand if husband-wife pairs commonly held cofradía offices during the colonial period. I suspect this is a modern adaptation, as cargo-holding has become an economic burden that necessitates participation of the entire household.

These modern adaptations reflect a long history of gendered individual and community creative responses to new challenges and changing circumstances. For Mesoamerican societies which had long linked motherhood and place-making, female religious leadership provided a way to establish new homes in the colonial context of voluntary and involuntary migration and resettlement. Like male leaders on town councils and cofradías, female cofradía officers worked to ensure community cohesion, autonomy, and survival in the face of colonial exploitation and disruption. The hidden history of female cofradía officers in colonial Chiapas sheds new light on the broader context of indigenous women's prominent leadership during major rebellions such as the Tzeltal Revolt of 1712, Cuscat's Rebellion (also known as the War of Saint Rose) in the Tzotzil highlands in the late 1860s, and the 1994 Zapatista uprising and ongoing political movement.Footnote 133 Female religious and public leadership in Chiapas's native communities has been triggered not only during moments of crisis. It has been a mundane, if mostly overlooked, part of daily life and community struggle for centuries.