Introduction

Historically, the western foothills of the Zagros Mountains have played a vital role as a natural defensive barrier. Archaeological evidence, including rock reliefs, steles and a Kudurru (boundary stone), together with cuneiform inscriptions, identify these mountains as a borderland between Mesopotamia and the Iranian Plateau during the late third millennium BC (Biglari et al. Reference Biglari, Alibaigi and Beyranvand2018). While this natural, topographically defined border played an important role in shaping both the ancient and modern geo-political landscape, defensive walls were also evidently in use throughout Iran's history—particularly in the Partho-Sasanian periods (fourth century BC to the sixth century AD). Evidence of the construction of defensive walls survives most notably in the long walls of Gurgan and Tammisha in north-eastern Iran, and Darband and Ghilghilchay in the Caucasus region on the northern borders of present-day Iran (Bivar & Fehérvári Reference Bivar and Fehérvári1966; Aliev et al. Reference Aliev, Gadjiev, Gaither, Kohl, Magomedov and Aliev2006; Nokandeh et al. Reference Nokandeh2006; Gadjiev Reference Gadjiev2008; Sauer et al. Reference Sauer, Rekavandi, Wilkinson and Nokandeh2013). Archaeological evidence suggests that these walls could, in fact, have formed part of a long defensive wall from the Yellow Sea in eastern China to the Black Sea in the west (Whitby Reference Whitby1985; Harmatta Reference Harmatta1996; Chang Reference Chang2006; Lovell Reference Lovell2006; Crow Reference Crow and Vagalinski2007; Wiewiorowski Reference Wiewiorowski2012; Labbaf-Khaniki Reference Labbaf-Khaniki, Horejs, Schwall, Muller, Luciani, Ritter, Guidetti, Salisbury, Hoflmayer and Burge2018).

In 2016, archaeological survey was undertaken in Sar Pol-e Zahab County, Kermanshah Province, in the lowlands of the western foothills of the Zagros Mountains. The survey targeted three plains, Beshive- Pa-Taq, Qaleh Shahin and Zahab, with the aim of identifying ancient sites. Situated on the Great Khorasan route, or the ‘Zagros Gate’ and ‘Asia Gate’ (Herzfeld Reference Herzfeld1920), the region is rich in archaeology, with rock reliefs and inscriptions (Börker-Klähn Reference Börker-Klähn1982; Vanden Berghe Reference Vanden Berghe1984). It is also referenced in historical texts (e.g. Moshir al-Dowleh Mohandesbashi Reference Moshir al-Dowleh Mohandesbashi1969 [1348]). The survey identified 193 sites dating from the Middle Palaeolithic to late Islamic periods, including a previously archaeologically unknown long wall, referred to locally as the Gawri Wall (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of the Gawri Wall in western Iran (after Labbaf-Khaniki Reference Labbaf-Khaniki, Horejs, Schwall, Muller, Luciani, Ritter, Guidetti, Salisbury, Hoflmayer and Burge2018: fig. 1).

Gawri Wall

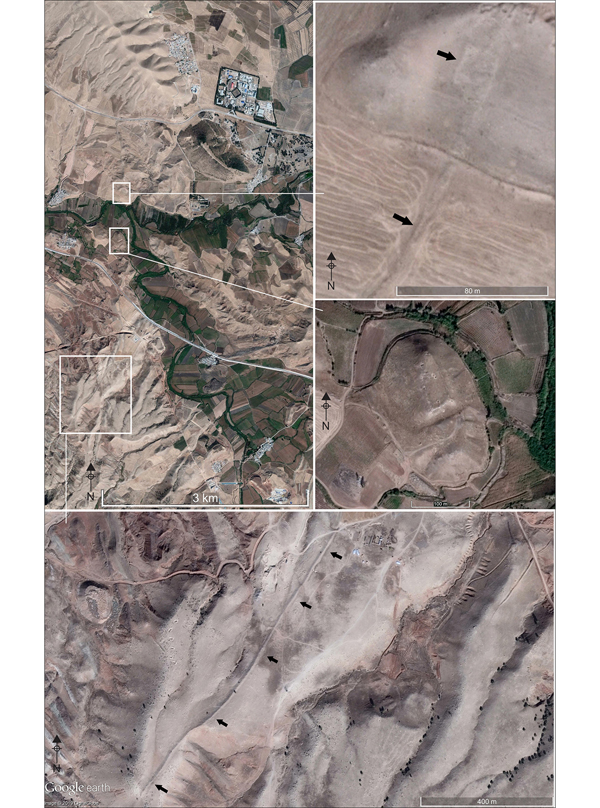

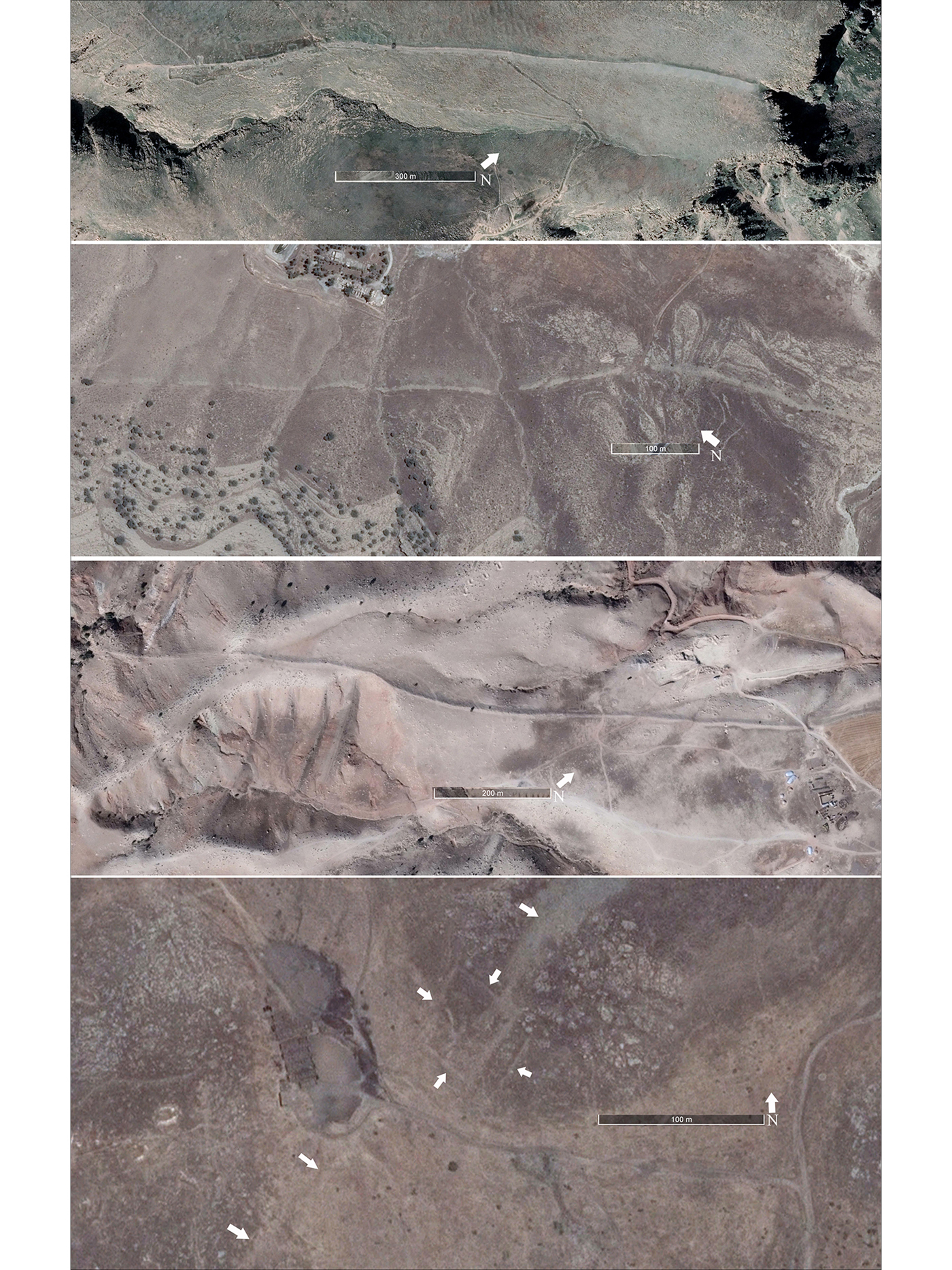

Remnants of a dry stone wall, known as the ‘Gawri Wall’ or ‘Gawri Chen Wall’, were discovered at Sar Pol-e Zahab in western Iran, near the present-day Iranian-Iraqi border (Figures 2–4). The wall comprises natural local materials, such as cobbles and boulders, with gypsum mortar surviving in places. The wall runs from north to south over the western mountains of Sar Pol-e Zahab, extending almost 115km from the Bamu Mountains in the area of Salas-e Bābājāni in the north of Sar Pol-e Zahab County, to Zhaw Marg Village near Guwaver of Gilan-e-Gharb in the south of Sar Pol-e Zahab County. The poor preservation of the wall precluded exact measurement of its width and height, but we estimate it to have been four metres wide and approximately three metres high. Remnants of structures, now destroyed, are visible in places along the wall. These may have been associated turrets or buildings (Figure 5). The route of the wall seems to have been determined by the topography of the area, and it frequently crosses mountain ridges, reaching significant heights (Figure 6). We surveyed approximately 250km2 of the Sar Pol-e Zahab region intensively, tracing the line of the wall to where it extended beyond the northern and southern extents of our survey area.

Figure 2. Location of the Gawri Wall in western Iran (figure courtesy of O. Sorkhabi).

Figure 3. The Gawri Wall in the western mountains of Sar Pol-e Zahab; arrows indicate the line of the wall (photograph by F. Fatahi).

Figure 4. Location of the Gawri Wall in Salmaneh Mount, south-east of Bamu mount (photograph by S. Alibaigi).

Figure 5. Satellite images of the Gawri Wall and castle, and structures along the Wall (© Google Earth 2019).

Figure 6. Satellite images of the Gawri Wall and a structure along the Wall (© Google Earth 2019).

Establishing an exact date for the wall's construction is challenging, but with an estimated volume of approximately one million cubic metres of stone, it would have required significant resources in terms of workforce, materials and time. Other monumental projects in the region to the east of the wall include Qaleh Yazdgird (a large Partho-Sasanian castle and the most important defensive site in the region), the irrigation system known as Nahr-e Balash (Vologases Creek) and the ancient City of Hulwān. These sites demonstrate that such resources were available in the Parthian and Sasanian periods. Equally impressive constructions survive to the west of the wall in the Diyala region, such as the remains of the Sasanian city Gawr Tepe (Casana & Glatz Reference Casana and Glatz2017: 12–16). The discovery of Partho-Sasanian potsherds at several locations along the wall could suggest that it was first built during the Partho-Sasanian period and was subsequently restored. This date, however, should remain speculative until further investigations are undertaken.

The political nature of the wall remains unknown; it is unclear whether it was defensive or symbolic. Neither can we determine who it was built by. Historical texts may support the necessity for a wall at a later date. For example, the Treaty of Zuhab—the 1639 accord that ended the Ottoman-Safavid war—records that Sar Pol-e Zahab was considered the border between Iran and the Ottoman Empire (Moshir al-Dowleh Mohandesbashi Reference Moshir al-Dowleh Mohandesbashi1969 [1348]: 44). Later, the 1847 Treaty of Erzurum showed this political border as the line between the plain and the mountains, just a little farther to the west (Lesan al-Molk Sepehr Reference Lesan al-Molk Sepehr1998 [1377]: 191; Etemad al-Saltaneh Reference Etemad al-Saltanehn.d.: 1681). While these sources may suggest that the wall was constructed during the Ottoman period, neither the wall nor its construction are mentioned in any Ottoman or Safavid texts. Furthermore, the traditional local nomenclature for the wall (Gawri Wall) suggests a pre-Islamic origin.

Conclusion

The archaeological record of the Sar Pol-e Zahab region suggests that construction of such a monumental wall would only have been possible from the Parthian period (third century BC) onwards. Indeed, ceramic finds from along the wall support a construction date during the Parthian or Sasanian period. Regional settlement patterns and the results of excavations reveal that, at this time, the construction of the wall could have been by order of a Parthian or Sasanian king, then implemented by a regional king or member of the nobility in Qaleh Yazdgirdor, or one of the influential castles in the area. Parts of the boundary marked by the wall have long represented a border, from the third millennium BC through the Parthian, Sasanian, Ottoman and Qajar periods, up to the present day. The survey team aims to continue research in the area to understand more fully the archaeological landscape of this region and the nature of the Gawri Wall.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sirous Adib in the Cultural Heritage and Handicraft office of Gilangharb, Kermanshah, for sharing information about the southern part of the wall, and M. Labbaf Khaniki for providing Figure 1.